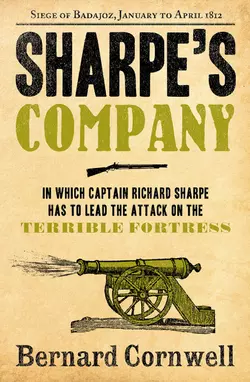

Sharpe’s Company: The Siege of Badajoz, January to April 1812

Bernard Cornwell

Captain Richard Sharpe has to lead the attack on the terrible fortress.It is a hard winter. For Richard Sharpe it is the worst he can remember. He has lost command to a man who could buy the promotion Sharpe covets. His oldest enemy, the ruthless and indestructible Hakeswill, joins the regiment and he is a man with a mission to ruin Sharpe.But Sharpe is determined to change his luck. The only way – a desperate choice – is to volunteer the Forlorn Hope, to lead the attack on the impregnable fortress town of Badajoz, a road to almost certain death or, just possibly, to heroic glory.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.

SHARPE’S

COMPANY

Richard Sharpe and the Siege of Badajoz,

January to April 1812

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1982

Previously published in paperback by Fontana 1983

Reprinted eleven times

Copyright © Rifleman Productions Ltd 1982

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is a work of fiction.

The incidents and some of the characters portrayed in it, while based on real historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007276233

Ebook Edition © March 2012 ISBN: 9780007334551

Version: 2018-12-05

Sharpe’s Company is for the Harper family, Charlie and Marie, Patrick, Donna and Terry, with affection and gratitude

‘Brilliant! Sharpe is a great creation’

Daily Mirror

‘Now thou art come unto a feast of death’

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

HENRY VI, PART I, ACT 4, SCENE 5.

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u93454e88-6e0d-5d87-b792-645618d2d898)

Copyright (#uceb1343d-52ea-5bd3-8c52-b3555f658b16)

Dedication (#u57a03c9b-b1d3-5f58-bcd7-5271f4da38fa)

Epigraph (#u28740fcb-6093-5e34-ba00-b9ab4009b9c1)

Map (#u2be1faa4-d4a9-5f7c-836c-004e8969023b)

Part One: January 1812 (#u648c3c25-d1d3-5e56-904d-d5a2a062e571)

Chapter One (#uf78258e5-62a7-59b2-bb71-5a5ace1c5f5f)

Chapter Two (#u7a036902-cefc-5692-a1e3-110cd362cdb3)

Chapter Three (#u6efb6ac3-3f2b-5892-b8e6-1d012ead85a5)

Chapter Four (#ucf89fbd3-d428-5a65-a871-846a0ce2d8fa)

Chapter Five (#ue42351d7-a6e0-58c1-8963-0335b8f55bea)

Chapter Six (#u87c603f2-423d-5902-aef4-f6b9321dbe33)

Chapter Seven (#ufc259dd1-d0d5-5403-98f5-0f87df63fc64)

Part Two: February–March 1812 (#u5dab2f82-6180-5e27-a398-bf7aa43f6d89)

Chapter Eight (#u23c56f7e-87b0-54b9-b0bb-38786e03c99c)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: St Patrick’s Day, March 17th to Easter Sunday, March 29th 1812 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Four: Saturday, April 4th to Monday, April 6th 1812 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Sharpe’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order) (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication) (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Bernard Cornwell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

A pale horse seen a mile away at sunrise means the night is over. Sentries can relax, battalions stand down, because the moment for a surprise dawn attack has passed.

But not on this day. A grey horse would hardly have been visible at a hundred paces, let alone a mile, and the dawn was shredded with dirty cannon smoke that melded with the snow-clouds. Only one living thing moved in the grey space between the British and French lines; a small, dark bird that hopped busily in the snow. Captain Richard Sharpe, huddled in his greatcoat, watched the bird and willed it to fly away. Move, you bastard! Fly! He hated the superstition in himself. He had spotted the tiny bird and, quite suddenly and unbidden, the thought had come to him that unless the bird took wing within thirty seconds, then the day would end in disaster.

He counted. Nineteen, twenty, and still the damned bird hopped in the snow. He could not tell what kind of bird it was. Sergeant Harper would know, of course, the huge Irish sergeant knew all the birds, but knowing what kind of bird it was would not help. Move! Twenty-four, twenty-five, and in desperation he bundled a crude snowball and skittered it down the slope so that the small bird, startled, sprang up into the skeins of smoke with a couple of seconds to spare. A man must sometimes make his own luck.

God! But it was cold! It was all right for the French. They were behind the vast defences of Ciudad Rodrigo, sheltered in the town’s houses and warmed by wide hearths, but the British and Portuguese troops were in the open. They slept by vast fires that died in the night and yesterday, at dawn, four Portuguese sentries had been discovered frozen, their greatcoats iced to the ground, dead by the river. Someone had tipped them in, breaking the Agueda’s thin ice, because no one wanted to dig graves. The army had taken its fill of digging; for twelve days they had done nothing else; batteries, parallels, saps and trenches, and they never wanted to dig again. They wanted to fight. They wanted to carry their long bayonets up the glacis of Ciudad Rodrigo, to go into the breach, to kill the French, and take those fires and houses for themselves. They wanted to be warm.

Sharpe, Captain of the South Essex’s Light Company, lay in the snow and stared through his telescope at the largest breach. He could not see much. Even from the hillside, five hundred yards from the town, the snow-covered slope of the glacis hid all but the top few feet of Ciudad Rodrigo’s main wall. He could see that the British guns had done damage and knew that the stones and rubble must have cascaded into the hidden ditch to make a crude ramp, perhaps a hundred feet wide, up which the attackers must climb to get into the heart of the fortress town. He wished he could see beyond the breach to the alleyways at the foot of the shot-scarred church tower that was so close to the walls. The French would be busy there, building new defences, siting fresh cannon, so that when the attack burst over the rubbled mound of the breach it would be met with precisely planned horror, flame and grapeshot, death in the night.

Sharpe was afraid.

It was a strange knowledge, known to him alone, and he was ashamed of it. It was not certain that the attack would be on this day, but the army, with the instinct of men who know that the time has come, were confident that Wellington would order the assault this night. No one knew which battalions would be chosen, but whichever units were to brave the assault they would not be the first attackers to climb the breach. That was a job only for volunteers, the ‘Forlorn Hope’, whose suicidal task was to draw the defenders’ fire, force them to spring their carefully prepared traps, and clear a bloody path for the battalions that followed. Not many of the Forlorn Hope would live. The Lieutenant who commanded, if he was still alive, would receive his Captaincy on the spot and his two Sergeants would be made Ensigns. The promises of promotion were easily given because they rarely had to be kept, yet there was never a shortage of volunteers.

The Forlorn Hope was for the brave. It may have been a courage born of desperation, or foolhardiness, but it was courage just the same. Men who survived a Hope were marked for life, famous among their comrades, envied by lesser men. Only the Rifle Regiments gave a badge to the survivors, a laurel-wreath that was sewn to the sleeve, but Sharpe did not hanker after medals. He simply wanted to survive a test, the supreme test of almost certain death because he had never been in a Forlorn Hope. It was a foolish desire, and he knew it, but it was there.

It was not just a test. Richard Sharpe wanted the promotion. He had joined the army at sixteen, as a Private, and worked his way through the ranks until he was a Sergeant. On the battlefield of Assaye he had saved the life of Sir Arthur Wellesley and had been rewarded with the telescope and a commission. Ensign Sharpe risen from the gutter, but still ambitious, still needed to prove, day after day, that he was a better soldier than the privileged sons who purchased their promotions and climbed the officers’ ladder with monied ease: Ensign Sharpe became Lieutenant Sharpe and, wearing a new uniform, the dark green of the 95th Rifles, he fought his way through Northern Spain and Portugal; the Corunna retreat, Rolica, Vimiero, the Douro crossing, and Talavera. He had taken the French Eagle at Talavera when he and Sergeant Harper had hacked their way into an enemy battalion, cut down the standard bearer, and brought the trophy back to Wellesley. He became the Viscount Wellington of Talavera. And Sharpe had been gazetted, just before the battle, as a Captain. It was the promotion he most wanted; the chance to lead his own Company, but the gazette was now two and a half years old and it was still unapproved.

He could hardly believe it. In July he had gone back to England and spent the last six months of 1811 recruiting in London and the Shires for the shrinking South Essex Regiment. He had been feted in London, dined by the Patriotic Fund, and presented with a fifty-guinea sword for the capture of the French Eagle. The Morning Chronicle had dubbed him ‘the scarred Hero of the Field of Talavera’ and suddenly, for a few days at least, everyone had wanted to meet the tall, dark-haired Rifleman with the scar that gave his face an unnatural, mocking expression. He had felt out of place in the draped softness of London’s drawing rooms and had covered his discomfort by shrinking into silent watchfulness. The reticence had been thought dangerously attractive by his hostesses who had kept their daughters upstairs and the Rifle Captain to themselves.

But the Hero of the Field of Talavera was nothing but a nuisance to the Army Headquarters in the Horse Guards. It had been a mistake, a stupid mistake, but he had visited Whitehall and been shown to a bare waiting room. The autumn rain had spattered through a high, broken window as he sat, his huge sword across his knees, while a clerk with smallpox scars tried to find what had happened to the gazette. Sharpe simply wanted to know whether he was a real Captain, sanctioned as such by the Horse Guards’ approval, or merely a Lieutenant in borrowed and temporary rank. The clerk had kept him waiting three hours, but at last returned to the room. ‘Sharpe? With an “e”?’

Sharpe nodded. Around him a group of half-pay officers, sick, lame or half-blind, listened curiously. They were all seeking appointments and hoping Sharpe would be disappointed. The clerk blew dust off the papers in his hand.

‘It’s irregular.’ He peered at Sharpe’s dark green jacket. ‘You said the South Essex Regiment?’

‘Yes.’

‘But that, if I’m not mistaken, and I rarely am, is the uniform of the 95th?’ The clerk gave a small, self-satisfied laugh, as if in celebration of a small victory. Sharpe said nothing. He wore the uniform of the Rifles because he was proud of his old Regiment, because the job with the South Essex was only ever intended as a temporary attachment, and how was he to tell this pinched bureaucrat about leading his small band of Riflemen from the horrors of the Corunna retreat down to join the army in Portugal where they had been arbitrarily joined to the redcoats of the South Essex. The clerk twitched his nose and sniffed. ‘Irregular, Mr Sharpe, very irregular.’ He selected the top piece of paper with ink-stained fingers. ‘This is the document.’

He held Sharpe’s gazette as if the document might reinfect him with smallpox. ‘You were given a Captaincy in 1809?’

‘By Lord Wellington.’

The name cut no ice in Whitehall. ‘Who should have known better. Dear me, Mr Sharpe, he should have known better! It’s irregular.’

‘But not unknown, surely?’ Sharpe had suppressed his urge to vent his irritation on the clerk. ‘I thought it was your job to approve these documents.’

‘Or disapprove them!’ The clerk laughed again and the half-pay officers grinned. ‘Disapprove, Mr Sharpe, or disapprove!’ Rain fell down the chimney and hissed on the meagre coal fire. The clerk, his thin shoulders heaving with silent laughter, tugged a pair of spectacles from the recesses of his clothing and clipped them on to his nose as if the gazette, seen through smeared glass, might reveal new cause for merriment. ‘We disapprove them, sir, most of the time. You allow one and you allow all. It upsets the system, you know. There are rules, regulations, standing orders!’ And the clerk shook his head because it was obvious Sharpe understood nothing of the army.

Sharpe waited for the head-shaking to cease. ‘It seems to have taken you a long time to make any decision on this gazette.’

‘And still not made!’ The clerk said it proudly, making it seem that the length of time proved the gravity of the Horse Guards’ wisdom. Then he seemed to relent and offered Sharpe a rueful smile. ‘The truth is, Mr Sharpe, that there was a mistake. A regrettable mistake and your visit has happily rectified the mistake.’ He peered over his glasses at the tall Rifleman. ‘We are really most grateful to you for drawing it to our attention.’

‘Mistake?’

‘It was filed wrongly.’ The clerk plucked another piece of paper from his left hand. ‘Under Lieutenant Robert Sharp, no “e”, who died of the fever in 1810. His papers were, otherwise, in perfect order.’

‘Which mine are not?’

‘Indeed, no, but you are still alive.’ The clerk looked peevishly at Sharpe. ‘We do a have a chance of tidying up when an officer is translated to glory.’ He took off his glasses and cleaned them with Sharpe’s folded gazette. ‘It will be attended to, Mr Sharpe, with expedition. I promise you. With expedition!’

‘Soon?’

‘That’s what I said, isn’t it? It would be wrong to say more.’ The clerk pushed his spectacles back into place. ‘Now, if you’ll pardon me, there is a war on and I have other duties!’

It had been a mistake, Sharpe realized afterwards, to visit Whitehall, but it was done and he could only go on waiting. Surely, he told himself a dozen times each day, they could not disapprove the gazette. Not after he had taken the Eagle? After he had brought the gold out of the burning Almeida, and after he had savaged the finest French troops in the deathtraps of Fuentes de Oñoro? He stared gloomily across the snow at the scar in Ciudad Rodrigo’s defences. He knew he should have volunteered for the Forlorn Hope. If he had led it, and survived, then no one could have denied him the Captaincy. He would have proved himself, captured the rank, and the pox-scarred bureaucrats of Whitehall could scratch themselves into a well-ordered eternity because nothing they could do, nothing, could have taken the Captaincy away from him. A pox on the bloody lot of them!

‘Richard Sharpe!’ A quiet voice behind him, full of pleasure, and Sharpe twisted round.

‘Sir!’

‘I could feel a pricking in my thumbs! I knew you had to be back with the army.’ Major Michael Hogan slithered on the snow towards him. ‘How are you?’

‘I’m well.’ Sharpe scrambled to his feet. He beat the snow off his greatcoat and shook Hogan’s gloved hand.

The Engineer laughed at him. ‘You look like a drowned tinker, so you do, but it’s good to see you.’ The Irish voice was rich and warm. ‘And how was England?’

‘Cold and wet.’

‘Ah well, it’s a Protestant country.’ Hogan conveniently ignored the freezing dampness of the Spanish countryside around them. ‘And how is Sergeant Harper? Did he enjoy England?’

‘He did, and most of what he enjoyed was plump and giggled.’

Hogan laughed. ‘A man of sense. You will give him my best wishes?’

‘I will.’ The two men stared at the town. The British siege guns, long, iron twenty-four-pounders, were still firing, their reports muffled by the snow, and their shots erupting flurries of snow and stone from the walls either side of the main breach. Sharpe glanced at Hogan. ‘Is it a secret we’re attacking tonight?’

‘It is a secret. Everyone knows, of course, they always do. Even before the General. Rumour has it for seven o’clock.’

‘And does rumour extend to the South Essex?’

Hogan shook his head; he was attached to Wellington’s staff and knew what was being planned. ‘No, but I was hoping I could persuade your Colonel to lend me your Company.’

‘Mine?’ Sharpe was pleased. ‘Why?’

‘Not for much. I don’t want you lads in the breach, but the Engineers are short-handed, as ever, and there’s a heap of stuff to be carried up the glacis. Would you be happy?’

‘Of course.’ Sharpe wondered whether to tell Hogan of his wish that he had gone with the Forlorn Hope, but he knew that the Irish Engineer would think he was mad, so he said nothing. Instead he lent Hogan his telescope and waited silently as the Engineer stared at the breach. Hogan grunted. ‘It’s practical.’

‘You’re sure?’ Sharpe took the glass back, his fingers instinctively feeling for the inlet brass plate; ‘In Gratitude. AW. 23 September 1803’.

‘We’re never sure. But I can’t see it getting any better.’ The Engineers had the job of pronouncing when a breach was ‘practical’, when, in their judgment, the rubble slope could be climbed by the attacking infantry. Sharpe looked at the small, middle-aged Major.

‘You don’t sound very happy.’

‘Of course not. No one likes a siege.’ Hogan was trying, like Sharpe earlier, to imagine what horrors the French had prepared in the breach. A siege, in theory, was the most scientific of all fighting. The attackers battered holes in the defence and both sides knew when the breaches were practical, but the advantage was all with the defenders. They knew where the main attack was coming, when, and roughly how many men could be fed into the breach. There the science stopped. There was great skill needed to site the batteries, in sapping forward, but once the science of the Engineers had opened up the breach, it was left to the infantry to climb the defences and die on the rubble. The siege guns did what they could. They would fire till the last moment, as they were firing now, but soon the bayonets would take over and only raw anger would take the attackers through the prepared horror. Sharpe felt again the fear of going into a breach.

The Irishman seemed to sense his thoughts. He clapped Sharpe on the shoulder. ‘I’ve a feeling about this one, Richard. It’s going to be all right.’ He changed the subject. ‘Have you heard from your woman?’

‘Which one?’

Hogan snorted. ‘Which one! Teresa, of course.’

Sharpe shook his head. ‘Not for sixteen months. I don’t know where she’s been.’ Or even, he thought, if she was still alive. She fought the French in the ‘Guerrilla’, the ‘little war’, and the hills and rocks of her battles were not far from Ciudad Rodrigo. He had not seen her since they parted below Almeida and, thinking of her, he felt a sudden longing inside him. She had the face of a hawk, slim and cruel, with dark hair and eyes. Teresa was beautiful as a fine sword was beautiful; slim and hard.

Then, in England, he had met Jane Gibbons whose brother, Lieutenant Christian Gibbons, had tried to kill him at Talavera. Gibbons had died. Jane Gibbons was beautiful as men dream of beauty; blonde and feminine, slim as Teresa was slim, but there the resemblance ended. The Spanish girl could strip a Baker rifle lock in thirty seconds, could kill a man at two hundred paces, could lay an ambush and knew how to give a captured Frenchman a lingering death as payment for her own mother’s rape and murder. Jane Gibbons could play the pianoforte, write a pretty letter, knew how to use a fan at a county dance, and took her delight in spending money at Chelmsford’s milliners. They were as different from each other as steel is from silk, yet Sharpe wanted both, though he knew such dreams were futile.

‘She’s alive.’ Hogan’s voice was soft.

‘Alive?’

‘Teresa.’ Hogan would know. Despite the shortage of Engineers, Wellington had put Hogan on his own staff. The Irishman spoke Spanish, Portuguese, and French, could break the enemy’s codes, and spent much of his time working with the Guerrilleros or with Wellington’s Exploring Officers who rode, alone and in uniform, behind French lines. Hogan collected what Wellington called his ‘intelligence’ and Sharpe knew that if Teresa were still fighting, then Hogan would have news.

‘What have you heard?’

‘Not much. She went south for a long time, by herself, but I heard she was back up here. Her brother is leading the band, not herself, but they still call her “La Aguja”.’

Sharpe smiled. He had given her the nickname himself; the needle. ‘Why did she go south?’

‘I don’t know.’ Hogan smiled at him. ‘Cheer yourself up. You’ll see her again. Besides, I’d like to meet her!’

Sharpe shook his head. It had been a long time and she had made no effort to find him. ‘There must be a last woman, sir, like a last battle.’

Hogan whooped with laughter. ‘God in heaven! A last woman. You gloomy bastard! You’ll be telling me next that you’re training for the Priesthood.’ He wiped a tear from his eye. ‘A last woman, indeed!’ He turned to stare once more at the town. ‘Listen, my friend, I must be busy, or I’ll be the last Irishman on Wellington’s staff. Will you look after yourself now?’

Sharpe grinned and nodded. ‘I’ll survive.’

‘That’s a useful delusion. It’s good you’re back.’ He smiled and began trudging through the snow towards Wellington’s headquarters. Sharpe turned back towards Ciudad Rodrigo. Survival. It was a bad time to be fighting. The turn of a year was when men looked ahead, dreamed of far-away pleasures, of a small house and a good woman, and friends of an evening. Winter was a time when armies stayed in their quarters, waiting for the spring sunshine to dry the roads and shrink the rivers, but Wellington had marched in the first days of the New Year, and the French garrison of Ciudad Rodrigo had woken one cold morning to find that war and death had come early in 1812.

Ciudad Rodrigo was just the beginning. There were only two roads from Portugal into Spain that could take the weight of heavy artillery, the endless grinding of supply carts, and the pounding of battalions and squadrons. Ciudad Rodrigo guarded the northern road and tonight, as the church bell sounded seven, Wellington planned to take the fortress. Then, as all the army knew, as all Spain knew, there was the southern road to capture. To be safe, to protect Portugal, to attack into Spain, the British must control both roads, and to control the southern road they must first take Badajoz.

Badajoz. Sharpe had been there, after Talavera and before the Spanish army had feebly surrendered the city to the French. Ciudad Rodrigo was big, but small compared with Badajoz; the walls in this snow looked formidable, but they were puny next to the bastions of Badajoz. Richard Sharpe let his thoughts go south, drifting with the cannon-smoke over Ciudad Rodrigo, south over the mountains, to where the vast fortress cast dark shadows on the cold waters of the Guadiana River. Badajoz. Twice the British had failed to take the city from the French. Soon they must try again.

He turned away, to rejoin his Company at the foot of the hill. There could be a miracle, of course. The garrison of Badajoz might get the fever, the magazine might blow up, the war might end, but Sharpe knew they were vain hopes in a cold wind. He thought of his Captaincy, of his gazette, and though he knew that Lawford, his Colonel, would never take the Light Company from his command, he still wondered why he had not volunteered for the Forlorn Hope. It would have made his rank secure and he would have passed the test of overcoming the fear that each man had of being first into a defended breach. He had not volunteered and if he could not prove his bravery, that had been proved so many times before, in the breach at Ciudad Rodrigo, then the proof would have to come later.

At Badajoz.

CHAPTER TWO

The orders came late in the afternoon, surprising no one, but stirring the battalions into quiet activity. Bayonets were sharpened and oiled, muskets checked and re-checked, and still the siege guns hammered at the French defences, trying to unseat the hidden, waiting cannon. Grey smoke blossomed out of the batteries and drifted up to join the low, bellying clouds that were the colour of wet gunpowder.

Sharpe’s Light Company, as Hogan had requested, were to join the Engineers on the approach to the largest breach. They would be carrying huge hay-bags that would be thrown down the steep face of the ditch to make a vast cushion on to which the Forlorn Hope and the attacking battalions could safely jump. Sharpe watched as his men filed into the forward trench, each holding one of the grotesquely stuffed bags. Sergeant Harper dropped his bag, sat on it, pummelled it into comfort, and then lay back. ‘Better than a feather bed, sir.’

Nearly one man in three of Wellington’s army came, like the Sergeant, from Ireland. Patrick Harper was a huge man, six feet four inches of muscle and contentment, who no longer thought it odd that he fought for an army not his own. He had been recruited by hunger from his native Donegal and kept in his head a memory of his homeland, a love of its religion and language, and a fierce pride in its ancient warrior heroes. He did not fight for England, less still for the South Essex Regiment, but instead he fought for himself and for Sharpe. Sharpe was his officer, a fellow Rifleman and a friend if it was possible for a Captain and a Sergeant to be friends. Harper was proud to be a soldier, even in his enemy’s army, because a man could take pride in doing a job well. One day, perhaps, he would fight for Ireland, but he could not imagine how that could happen because the land was crushed and persecuted, the flames of resistance trampled out, and, in truth, he did not give the prospect much thought or hope. For the moment he was in Spain and his job was to inspire, discipline, humour, and cajole the Light Company of the South Essex. He did it brilliantly.

Sharpe nodded at the hay-bag. ‘It’s probably full of fleas.’

‘Aye, sir, it probably is.’ Harper grinned. ‘But there’s no room on my body for another flea.’ The whole army was verminous; lice-ridden, flea-bitten, but so inured to the discomfort that they hardly noticed it. Tomorrow, thought Sharpe, in the comfort of Ciudad Rodrigo, they could all strip off, smoke out the lice and fleas, and crush the uniform seams with a hot iron to break the eggs. But that was tomorrow.

‘Where’s the Lieutenant?’

‘Being sick, sir.’

‘Drunk?’

Harper’s face flickered in a frown. ‘That’s not for me to say, sir.’ Which meant, Sharpe knew, that Lieutenant Harold Price was drunk.

‘Will he be all right?’

‘He always is, sir.’

Lieutenant Price was new to the Company. He was a Hampshire man, the son of a ship-builder, and gambling debts and unwanted pregnancies among the local girls had persuaded his sober, church-loving father that the best place for young Price was in the army. The ship-builder had purchased his son an Ensign’s commission and, four years later, had been happy to pay the five hundred and fifty pounds that had secured Master Price’s promotion to Lieutenant. The father had been happy because the vacant Lieutenancy was in the South Essex, a Regiment that was safely abroad, and he was glad to see as great a distance as possible between himself and his youngest son.

Robert Knowles, Sharpe’s previous Lieutenant, had gone. He had bought himself a Captaincy in a Fusilier Battalion, making the vacancy Price had purchased, and Sharpe, at first, had not liked the change. He had asked Price why, as the son of a ship-builder, he had not joined the navy.

‘Seasick, sir. Could never stand up straight.’

‘You can’t do that on land.’

Price had taken a few moments to understand, then his round, friendly, misleadingly innocent face had grinned. ‘Very good, sir. Droll. But still, sir, on land, if you follow me, there’s always something solid underneath. I mean if you fall over, then at least you know it’s the drink and not the bloody ship.’

The dislike had not lasted. It was impossible to dislike Lieutenant Price. His life was a single-minded pursuit of the debauchery denied him by his stern, God-fearing family, and he retained enough sense to make sure that when he was supposed to be sober he was, at the very least, upright. The men of Sharpe’s Company liked him, were protective towards him because they believed he was not long for this world. They reasoned that if a French bullet did not kill him, then the drink would, or the mercury salts he took for the pox, or a jealous husband, or, as Harper said admiringly, sheer bloody exhaustion. The big Sergeant looked up from his hay-bag, nodded down the trench. ‘Here he is now, sir.’

Price grinned weakly at them, winced as twenty-four pounds of roundshot hammered overhead towards the city, then stared agape at Harper. ‘What are you sitting on, Sergeant?’

‘Hay-bag, sir.’

Price shook his head in admiration. ‘Christ! They should issue them every day. Can I borrow it?’

‘My pleasure, sir.’ Harper stood up and courteously waved the Lieutenant to the bag.

Price collapsed, groaned in satisfaction. ‘Wake me when glory calls.’

‘Yes, sir. Which one’s Glory?’

‘Irish wit, oh God, Irish wit.’ Price closed his eyes.

The sky was darkening, the grey clouds turning sinister, bringing on the inexorable moment. Sharpe pulled his huge sword a few inches from the scabbard, tested the honed edge, and pushed it back. The sword was one of his symbols, with the rifle, which proclaimed he was a fighter. As a Light Company officer, he should have kept to the tradition that decreed he carried a Light Cavalry sabre. He hated the curved, light blade. Instead he used a Heavy Cavalry sword, straight-bladed and ill-balanced, that he had picked up from a battlefield. It was a brute of a weapon, thirty-five inches of cumbersome steel, but Sharpe was tall and strong enough to wield it easily. Harper saw Sharpe’s thumb test the edge. ‘Expecting to use it, sir?’

‘No. We don’t go beyond the glacis.’

Harper grunted. ‘There’s always hope.’ He was loading his seven-barrelled gun, a weapon of extreme unorthodoxy. Each of the barrels was a half inch wide and all seven were fired by a single charge that punched out a spray of death. Only six hundred had been made by the gunsmith, Henry Nock, and delivered to the Royal Navy, but the massive recoil had smashed men’s shoulders and the invention had been quietly discarded. The gunsmith would have been pleased to see the huge Irishman, one of the few men strong enough to handle the weapon, meticulously loading each twenty-inch barrel. Harper liked the weapon, it gave him a distinction similar to Sharpe’s sword, and the gun had been a present from his Captain; purchased from a chandler in Lisbon.

Sharpe pulled the greatcoat tight and peered over the parapet towards the city. There was little to see. The snow, glinting with a myriad of metallic sparks, led to the slope of the glacis which was a continuation of the hill on which Ciudad Rodrigo was built. He could see where the breach was hidden behind the glacis because of the dark scars in the snow where the siege artillery had fired short. The glacis was not designed to stop infantry. It was an earthen slope, easily climbed, that was banked in front of the defences to bounce the roundshot screaming over the defenders, and it had forced Wellington to capture the French forts on nearby hills so that the British artillery could be placed high up and fire down, over the glacis, into the walls.

Beyond the glacis was a ditch, hidden from Sharpe, that would be stone-faced and wide and, beyond the ditch, the modern walls that masked, in their turn, the old mediaeval wall. The guns had pierced both walls, old and new, and turned them into a stretch of rubble, but the defenders would have prepared horrid traps to guard the gap.

It was nine years since Sharpe had been part of a besieging force, yet he could remember clearly the fierceness of the fight as the British had climbed the hill to Gawilghur and plunged into the maze of walls and ditches that the Indians had defended with ferocious bravery. Ciudad Rodrigo should, he knew, be more difficult; not because the men who defended this town were better soldiers, but because, like Badajoz, it was defended with the science of modern engineering. There was something horridly precise about the defences, with their false walls and ravelins, their mathematically sited bastions and hidden cannons, and only passion, anger, or screaming desperation would force the science to yield to the bayonets. The desperation would not subside quickly. Sharpe knew that once the attackers broke through the breach, their blood raised to a desperate pitch, the men would be ungovernable in the town’s streets. It had always been so. If a fortress did not surrender, if its defenders forced the attackers to shed their blood in an assault, then old custom, soldiers’ custom, dictated that all inside the fortress belonged to the attackers’ vengeance. Ciudad Rodrigo’s only hope lay in a short, easy fight.

Bells rang the Angelus in the town. The Catholics in the Company, all Irish, made sketchy crosses and scrambled to their feet as Lieutenant-Colonel the Honourable William Lawford, the South Essex’s Commanding Officer, came into sight. He waved the men down, grinned at the sight of the snoring Price, nodded amicably to Harper, and came and stood beside Sharpe. ‘All well?’

‘Yes, sir.’

They were the same age, thirty-five, but Lawford had been born to the Officers’ Mess. When he had been a Lieutenant, lost and frightened in his first battle, Sergeant Richard Sharpe had been with him, guiding him as Sergeants often guide young officers. Then, when both men had been in the torture chambers of the Sultan Tippoo, Lawford had taught Sharpe to read and write. The skills had made it possible for Sharpe, once he had performed an act of suicidal bravery, to be made into an officer. Lawford stared over the parapet at the glacis. ‘I’ll come with you tonight.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Sharpe knew that Lawford had no need to be there, but also knew he could not dissuade him from coming. He glanced at his Colonel. As usual, Lawford was immaculately uniformed; gold lace glinting above the clean, yellow facings of the scarlet jacket. ‘Wear a greatcoat, sir.’

Lawford smiled. ‘You want me to disguise myself?’

‘No, sir, but you must be bloody cold, and we all like a shot at a fancy Colonel.’

‘I’ll wear this.’ Lawford held up a cavalry cloak, fur trimmed and lavish. The fastening was a gold chain at the neck and Sharpe knew the cloak would billow open and leave the uniform exposed.

‘It won’t hide the uniform, sir.’

‘No, Sergeant.’ Lawford smiled. He had spoken softly and the remark was an acknowledgement that their relationship was still the same, despite the promotions. Lawford was a good officer who had turned the South Essex from a frightened Regiment into a hardened, confident unit. But soldiering was not Lawford’s life; instead it was a means to his ends, political ends, and he wanted success in Spain to pave the way to power at home. In war he still relied on Sharpe, the natural soldier, and Sharpe was grateful for the trust and the freedom.

Beyond the river, towards Portugal, the fires of the British camp glowed bright in the dusk. In the trenches the battalions waiting for the assault shivered, gratefully drank the rum that was issued, and went through the tiny rituals that always preceded battle. Uniforms were pulled straight, belts made comfortable, weapons obsessively checked, and men felt in pockets or pouches for the talismans that kept them alive. A lucky rabbit’s foot, a bullet that had nearly killed them, a memento of home, or just a plain pebble that had caught their eye as they lay under heavy fire on a battlefield. The clocks moved up from the half hour towards the hour.

Generals fidgeted as they tried to persuade themselves their plans were as near perfect as possible, Brigade Majors fussed over last minute orders, while the men themselves wore that wary, stretched look that soldiers have before an event that demands their deaths to make it memorable. Packs were piled, to be guarded by men who would wait in the trenches, and bayonets were slotted and twisted on to musket barrels. The job, General Picton said, would be done with cold iron; and there would be no time to reload a musket in the breach, just to push on, bayonet out, reaching for the enemy. They waited for night. Made small jokes, fought with the imagination.

At seven it was dark. The big church clock in the tower that had been chipped and scarred by cannon balls, whirred as it geared itself to strike the hour. The sound was clearly audible over the snow. The orders must come soon. The siege guns stopped firing, a sudden silence that seemed unnatural after the days of hammering at the defences. Sharpe could hear men coughing, stamping their feet, and the little noises were terrible reminders of how small and frail men were against the defences of a fortress.

‘Go!’ The Brigade Majors had the orders. ‘Go!’

Lawford touched Sharpe’s shoulder. ‘Good luck!’

The Rifleman noticed the Colonel was still uncloaked, but it was too late now. There was a stirring in the trenches, a rustle as the hay-bags were pushed out of the trench, and then Harper was beside him and, beyond the Sergeant, Lieutenant Price, wide-eyed and pale. Sharpe grinned at them. ‘Come on.’

They climbed up on the fire-step, over the parapet, and went in silence towards the breach.

1812 had begun.

CHAPTER THREE

The snow was brittle, crunching beneath Sharpe’s boots, while behind him he could hear the sounds of men slipping in the whiteness, their breath rasping in the cold air, their equipment clinking as they started up the hill towards the glacis.

The crest of the defences were limned by a faint, red haze where the lights in the town, fires and bracketed torches, glowed in the night mist. It seemed unreal, but to Sharpe battles often seemed unreal, especially now as he climbed the snow-slope towards the silent, waiting town and with each step he expected the sudden eruption of cannon and the shriek of grape. Yet the defenders were quiet, as if they were oblivious of the mass of men who churned the snow towards Ciudad Rodrigo. In two hours at the most, Sharpe knew, it would all be over. Talavera had taken a day and a night, Fuentes de Oñoro all of three days, but no man could endure the hell of a breach for more than a couple of hours.

Lawford was beside him, the cloak still held over one arm and the gold lace reflecting the dim, red light ahead. The Colonel grinned at Sharpe; he looked, the Rifleman thought, very young.

‘Perhaps we’re surprising them, Richard.’

The answer was instant. From ahead, from the left and right, the French gunners put matches to the priming tubes, the cannons banged back on their trails, and the canisters were spat over the glacis. The crest of the defences seemed to erupt in great, boiling clouds of smoke that were lit by internal lances of flame that reached from the wall, over the ditch, to spear their tongues of light on to the snow-slope. Following the thunder, so close that the sounds were indistinguishable, came the explosions of the canisters. Each was a metal can packed with musket balls which were blown apart by a powder charge. The balls hammered down. The snow was spotted with crimson.

There were shouts far to the left and Sharpe knew that the Light Division, attacking the smaller breach, were pouring over the glacis into the ditch. He slipped on the snow, recovered, and shouted at his men. ‘Come on!’

The smoke rolled slowly from the glacis, carried south on the night wind, and was then put back by the gunners’ next volley. The canisters cracked apart again, the mass of men hurried as the shouts of officers and Sergeants drove them up the slope to the dubious safety of the ditch. Far back, behind the first parallel, a band played and Sharpe caught a snatch of the tune and then he was at the top of the slope, the ditch black beneath him.

There was a temptation to stay a few feet down the slope and hurl the bags hopefully into the darkness, but Sharpe had long taught himself that the few steps of which a man is afraid are the important steps. He stood on the crest, Lawford beside him, and shouted at his men to hurry. The hay-bags thumped softly down in the blackness.

‘This way! This way!’ He led them right, away from the breach, their job finished, and the Forlorn Hope were jumping down into the ditch and Sharpe felt a pang of envy.

‘Down! down!’ He pushed them flat on the crest of the glacis and the cannons crashed overhead so close that the Light Company could feel the lick of their hot breath. The battalions were coming behind to follow the Forlorn Hope. ‘Watch the wall!’ The best help that the Light Company could be now to the attack was to snipe over the ditch as soon as any target could be seen.

All was blackness. Sounds came from the ditch; boots scuffing, the scrape of a bayonet, a muffled curse, and then the scrabbling of feet on rubble that told him the Hope had reached the breach and were climbing the broken stone slope. Musket flashes dazzled from the breach summit, the first opposition to the Forlorn Hope, but the fire did not appear to be heavy and Sharpe could hear the men still climbing.

‘So far …’ Lawford left the sentence unfinished.

There were shouts from behind and Sharpe turned to see the attackers reaching the crest and jumping recklessly into the ditch. There were shouts as men missed the hay-bags, or landed on their comrades, but the leading battalions were in place, and they were going forward in the darkness, and Sharpe heard the growl that he remembered from Gawilghur. It was an eerie sound made by hundreds of men in a small place, steeling themselves to go into the narrow breach, and it was a sound that would last till the battle was decided.

‘It’s going well!’ Lawford’s face was nervous. It was going too well. The Hope had to be nearing the end of their long climb, the 45th and 88th were on their heels, and still the only French reaction was the few musket shots and the canister that still exploded far behind over the hurrying reserves. Something more had to be waiting in the breach.

A flame flickered on the walls, spread like fire catching on dry thatch, then heaved itself up into the air and down into the ditch. Another flame followed, then another, and the breach was lit like daylight as the carcasses, oil-soaked, hardpacked straw that was bound in tarred canvas, were lit and tossed into the ditch so that the defenders could see their targets. There was a cheer from the French, a triumphant, defiant cheer, and the musket balls plucked at the Forlorn Hope, revealed close to the summit of the jumbled stone slope, and the cheer was answered by the 45th and 88th as the battalions ran forward, a dark mass in the tangled maze of the ditch, and the assault began to look easy.

‘Rifles!’ Sharpe shouted. He had eleven Riflemen left, apart from Harper and himself, of the thirty men he had led away from the horrors of the Corunna retreat three years before. They were the core of his Company, the green-jacketed specialists, whose modern Baker rifles could kill at three hundred paces and more, while the smooth-bore musket, the Brown Bess, was virtually useless at more than fifty yards. He heard the distinctive crack of the weapons, less muffled than the muskets, and saw a Frenchman fall back as he tried to throw another burning carcass down the breach slope. Sharpe wished he had more rifles. He had trained some of his redcoats to use the weapon, but he would have liked more.

He ducked down beside Lawford. The French had switched to grapeshot that left the cannon barrels like duck shot from a fowling piece. He heard the whistle of balls over his head, saw a flame stab down into the ditch towards the crowded battalions, but in the fire-light he could see the redjacketed British were nearing the mid-point of their climb. The Forlorn Hope, still almost intact, were just paces from the top, their bayonets held out, while behind them the lower half of the breach was darkened by the mass of the assaulting column.

Lawford touched Sharpe’s arm. ‘It’s too easy!’

Muskets spat at the assault, but not enough to check the attack. The men in the ditch felt victory close, easily gained, and the column moved on to the breach like a beast uncoiling from the ditch. Victory was close, just seconds away, and the growl was a cheer that rose with the column’s climb.

The French had let them come. They let the Hope reach the very top of the shattered wall and then they unmasked the defence. There was a twin explosion, horrendous and earshattering, and flames startled across the breach. Sharpe winced. The cheer was laced with screams, spattered by the rattle of grapeshot, and he saw the French had mounted two guns, in hidden casements dug deep into the core of the walls either side of the breach, that could fire across the attack. They were not small guns, not field-guns, but massive pieces whose flames lanced clear across the full hundred feet width of the breach.

The Forlorn Hope disappeared, snatched into oblivion in a maelstrom of flame and grapeshot, and the head of the column was shattered by the gunfire that lacerated the upper half of the breach, clearing it with contemptuous ease. The growl faltered, turned into cries of alarm, and the column retreated, not from the guns, but from a new danger.

Flames appeared in the smoke-shrouded rubble, livid serpents that flickered in the stone, forked lightning that ran quicksilver down the scoured stones to touch the mines that had been hidden in the breach. The explosions tore the lower slope apart, flinging men and masonry into the air, blowing the first attack into failure. The meat-grinder of the breach had begun to turn.

The growl was still audible. The men from Connaught and Nottinghamshire were going back to the breach, over their mangled dead, past the blackened, smoking pits where the mines had been dug, and the French screamed insults at them; called them boy-lovers and weaklings, and followed the insults with more burning carcasses and lumps of timber or stone that avalanched on the slope and hurled men back into the blood-soaked base of the breach. The vast guns in their hidden, flanking casements were being reloaded, ready for their next targets, and they came, clawing their way up the blood-slick ramp till the thunder crashed again, the flames slapped at the breach, and the myriad scraps of grapeshot blasted the stones clear.

The assault had been bloodily repulsed, but there was no thought except to go forward. The foot of the ramp was crowded with the men of the two battalions who climbed again in the mindless, seething bravery of siege warfare.

Lawford clutched Sharpe’s arm, leaned close to his ear. ‘Those bloody guns!’

‘I know!’ They fired again, a fraction early, and it was plain that no man could climb past their fire. They were dug into the very heart of the town’s thick, low wall and no British siege gun could have hoped to reach them; not unless Wellington had fired at each hidden casement for a week until the whole wall collapsed like the breach itself. In front of each gun, revealed by the burning carcasses, was a trench that defended the gunners from their enemy on the breach, and as long as the two guns were firing, across and slightly ahead of each other, there could be no victory.

The troops were climbing again, slower now, wary of the guns and trying to avoid the burning grenades that the French were tossing on to the slope. The red explosions punctured the scattered attackers. Sharpe turned to Harper. ‘Are you loaded?’

The huge Sergeant nodded, grinned, and held up the seven-barrelled gun. Sharpe grinned back. ‘Shall we join in?’

Lawford shouted at them. ‘What are you doing?’

Sharpe pointed at the nearest side of the breach. ‘Going after the gun. Do you mind?’

Lawford shrugged. ‘Be careful!’

There was no time to think, just to jump into the ditch and pray that their ankles would not twist or break. Sharpe fell awkwardly, slipping on the snow, but a huge hand grabbed his greatcoat, hauled him upright, and the two men ran across the floor of the ditch. The jump had been twenty feet and it seemed as if they had fallen into the bottom of a giant cauldron, an alchemist’s vessel of fire, and the flames poured in from above. Carcasses rolled down, musket and cannon flame spat from above, and the fire spilt on to the living and dead flesh in the ditch and was reflected red on the underside of the low clouds that rolled southwards to Badajoz. There was only one way to live in the cauldron, and that was to go upwards, and the column was climbing again as Sharpe and Harper skirted the mass of men, and then the guns spoke, and the attack was flung back by the flame-borne grape-shot.

Sharpe had been counting the gaps between the shots and knew that the French gunners were taking about a minute to reload each giant gun. He counted the seconds in his head as the two men struggled past the mass of Irishmen to the left of the breach. They fought their way through the crush, going for the very edge of the slope, and the surge of men carried them forward so that, for an instant, Sharpe thought they would be carried on to the rubble slope itself. Then the guns fired again and the men ahead recoiled, something wet slapped Sharpe’s face, and the attack was broken into small groups. He had a minute. ‘Patrick!’

They threw themselves into the trench beside the breach, the trench that protected the gun. It was already filled with men sheltering from the grapeshot. The French gunners, over their heads, would be sponging out and desperately ramming the huge, serge bags of powder into the vast muzzles while other men waited with the lumpy, black bags of grapeshot. Sharpe tried to forget them. He looked up the wall to the casement’s lip. It was high up, far higher than a man’s height, so he braced his back on the wall, cupped his hands and nodded to the Sergeant. Harper put a massive boot into Sharpe’s hands, cocked the seven-barrelled gun, and nodded back. Sharpe heaved and Harper pushed up, the Irishman weighed as much as a small bullock. Sharpe grimaced with the effort and then two of the Connaught Rangers, seeing their intention, joined in and pushed up on Harper’s legs. The weight suddenly disappeared. Harper had grasped the casement’s edge with one hand, ignoring the musket bullets that flattened themselves on the wall beside him, threw the huge gun over the edge, aimed blindly, and pulled the trigger.

The recoil slammed him back, cruelly throwing him on the opposite lip of the trench, but he scrambled to his feet, screaming in Gaelic. Sharpe knew he was telling his countrymen to climb the wall and attack the gun crew while they were still dazed by the shattering blast. But it was hopeless trying to climb the steep wall, and Sharpe thought of the surviving gunners loading the huge cannon. ‘Patrick! Throw me!’

Harper seized Sharpe like a bag of oats, took one breath, and threw him bodily upwards. It was like being lifted by a mine explosion. Sharpe flailed, his rifle slipping from his shoulder, but he caught it by the barrel, saw the casement’s edge and desperately threw out his left hand. It held, he had a leg on the stonework; he knew the French muskets were firing at him, but he had no time to think of that for a man was running at him, a rammer raised to strike down, and Sharpe struck out with his rifle. It was a lucky effort. The brass-hilted butt caught the Frenchman on the temple, he staggered back, and Sharpe had dropped over the casement, found his feet, and the huge sword rasped out of the scabbard and the joy was there.

The gunners had been hit hard by the seven bullets that had ricocheted round the stone emplacement. Sharpe could see bodies lying beneath the huge, iron barrel of what he recognized as a siege gun, but there were still men alive and they were coming at him. He swung the long blade at them, drove them back, hacked down with the sword and felt it shudder as it cleaved a skull. He screamed at them, scaring them, slipped on new blood, tugged the blade free and swung again. The French went back. They outnumbered him six to one, but they were gunners more used to killing at a distance than seeing the face of their enemy wild over a naked sword. They cowered back and Sharpe turned, back to the casement’s edge, and found an arm clinging desperately to the stonework. He grabbed the wrist and heaved a Connaught Ranger into the sunken gun-pit. The man’s eyes were bright with excitement. Sharpe yelled at him. ‘Help the others up! Use your sling!’

A musket ball went past his head, clanging off the barrel of the gun, and Sharpe whirled to see the familiar uniforms of French infantry running down the stone stairs to rescue the gun. He went for them, wild with the madness of battle, and the crazy thought whirled in his head that he wished the mean-faced bastard clerk in Whitehall could see him now. Perhaps then Whitehall would know what its soldiers did, but there was no time for the thought because the infantry were coming down the narrow space beside the barrel. He leaped at them, shouting and lunging with the point to drive them back and he knew he was outnumbered.

They checked, let him come, and then countered with their long bayonets. The sword was not long enough! He swung at them, smashing bayonets to the side, but another came past his swing and he felt the blade catch in his greatcoat. He seized the barrel with his left hand, pulled the man off balance and brought the great brass hilt of the sword down on his head. He was forced back. Another bayonet flickered at him, making him dodge wildly so that he slipped against the siege gun, his sword was whirling uselessly, flailing for balance, and he saw the bayonets above him. His anger was useless because he could not parry.

The shout was in a language he did not speak, but the voice was Harper’s and the massive Irishman was crunching the enemy with the seven-barrelled gun held like a club. He ignored Sharpe, stepped over him, laughed at the French, swung at them and went forward as his ancestors had gone into fine, dawn-misted battles. He chanted the same words that his ancestors had, and the Connaught men were beside him and no troops in the world could have stood against their anger and their attack. Sharpe ducked under the barrel and there were more enemy, fearful now, and he hacked up with the blade, drove them back, stabbed with it, screaming the challenge. The French scrambled for the stone stairs in their rear, and the crazed men in red and green coats came on, stepping over the bodies, hacking and clawing at them. Sharpe felt the blade grate on a rib and he swung it clear, and suddenly the only enemy were the survivors who cowered at the foot of the stairs, shouting their surrender. They had no hope. The men of Connaught had lost friends on the breach, old friends, and the blades were used in short, efficient strokes. The bayonets ignored the French cries, worked swiftly, and the casement was thick with the smell of fresh blood.

‘Up!’ There were still enemies on the wall, enemies that could fire down into the gun-pit, and Sharpe climbed the stairs, the sword a streak of reflected firelight ahead of him, and suddenly the night air was cool and clear and he was on the wall. The infantry had fallen back down the ramparts, fearful of the carnage round the gun, and Sharpe stood at the stair’s head and watched them. Harper joined him, with a group of red-jacketed 88th, and they panted so that their breath fogged.

Harper laughed. ‘They’ve had enough!’

It was true. The French were pulling back, abandoning the breach, and only one man, an officer, tried to force them back. He shouted at them, beat at them with his sword, and then, seeing that they would not attack, came on himself. He was a slim man with a thin, fair moustache beneath a straight, hooked nose. Sharpe could see the man’s fear. The Frenchman did not want to make a solo attack, but he had his pride, and he hoped his men would follow. They did not. Instead they called to him, told him not to be a fool, but he walked on, looking at Sharpe, and his sword was ridiculously slim as he lowered it to the guard. He said something to Sharpe, who shook his head, but the Frenchman insisted and lunged at Sharpe, who was forced to leap back and bring up the huge sword in a clumsy parry. Sharpe’s anger had gone in the cool air, the fight was over, and he was irritated by the Frenchman’s insistence. ‘Go away! Vamos!’ He tried to remember the words in French, but he could not.

The Irish laughed. ‘Put him over your knee, Captain!’ The Frenchman was little more than a boy, ridiculously young, but brave. He came forward again, the sword level, and this time Sharpe jumped towards him, growled, and the Frenchman rocked back.

Sharpe dropped his own blade. ‘Give up!’

The answer was another lunge that came close to Sharpe’s chest. He leaned back and beat the sword aside. He could feel his anger returning. He swore at the man, jerked his head down the ramparts, but still the fool came forward, incensed by the Irish laughter, and again Sharpe had to parry and force him back.

Harper finished the farce. He had worked his way behind the officer and, as the Frenchman looked at Sharpe for another attack, the Sergeant coughed. ‘Sir? Monsewer?’ The officer looked round. The giant Irishman smiled at him, came forward unarmed and very slowly. ‘Monsewer?’

The officer nodded to Harper, frowned, and said something in French. The huge Sergeant nodded seriously. ‘Quite right, sir, quite right.’ Then a giant fist travelled from some place low down, up, and straight on to the Frenchman’s chin. He crumpled, the Connaught men gave an ironic cheer, and Harper laid the senseless body beside the rampart. ‘Poor wee fool.’ He grinned at Sharpe, immensely pleased with himself, and looked over towards the breach. The fight still went on, but Harper knew his part in the assault was done, and well done, and that nothing could touch him this night. He jerked his thumb at the Connaught Rangers and looked at Sharpe. ‘Connaught lads, sir. Good fighters.’

‘They are.’ Sharpe grinned. ‘Where’s Connaught? Wales?’

Harper made a joke at Sharpe’s expense, but in Gaelic, so that he was forced to listen to the Rangers’ good-humoured laughter. They were in good spirits, happy, like the Sergeant from Donegal, that they had played a good part in this night’s fight, a part that would make a fine story to weave through the long winter nights in some unimaginable future. Harper knelt to go through the unconscious Frenchman’s pockets and Sharpe turned to look at the breach.

The 45th, on the far side, were dealing with the second gun. They had found planks, abandoned in the trench, and thrown them over to the casement lip and Sharpe watched, admiringly, as the Nottinghamshire men charged across the perilous path and took their long bayonets to the gun crew. The growl had become a whoop of victory and the dark beast in the ditch uncoiled across the undefended breach and swarmed past the two silent guns towards the streets of the town. A few shots came from doors and windows, but only a few, and the British horde flooded down the rubble to where the breach had smothered the old mediaeval wall. It was over.

Or nearly. A second mine had been put in the ruins of the old wall. Black powder had been crammed into an old postern and now the French lit the fuse and ran back into the streets. The mine exploded. Flame streaked up from the darkness, old stones shattered outwards, boiling smoke and dust, and with it came the stench of roasted flesh and the head of the victorious column was uselessly decimated. For a second there was a stunned silence, time just to draw breath, and then the shout was not for victory, but for revenge, and the troops took their anger into the defenceless streets.

Harper watched the howling mob flow into the city. ‘You think we’re invited?’

‘Why not?’

The Sergeant grinned. ‘God knows, we’ve deserved it.’ He was dangling a gold watch and chain and he started forward towards the ramp that led down towards the houses. Sharpe followed and suddenly stopped. He froze.

Down where the second mine had exploded, lit by a flickering length of old timber, was a mangled body. One side seemed sleek with new blood, a sleekness speckled with the ivory of bone, but the other side was gorgeous in yellow facings and gold lace. A fur-trimmed cavalry cloak covered the legs. ‘Oh God!’

Harper heard him and saw where he was looking. Then both men were racing down the ramp, slipping on ice and slushy snow, and running towards Lawford’s body.

Ciudad Rodrigo was won; but not at this price, Sharpe thought, dear God, not at this price.

CHAPTER FOUR

There was a scream from inside the town, shots as men blew open the doors of houses, and over it all the sound of triumphant voices. After the fight, the reward.

Harper reached the body first, plucked the cloak to one side, and bent over the bloodied chest. ‘He’s alive, sir.’

It seemed to Sharpe like a parody of life. The explosion had sheared Lawford’s left arm almost clean from his body, crushed the ribs and flicked them open so they protruded through the remnants of skin and flesh. The blood was flowing beneath the once immaculate uniform. Harper began tearing the cloak into strips, his mouth a tight line of anger and sorrow. Sharpe looked towards the breach where men still clambered towards the houses. ‘Bandsmen!’

The bands had played during the assault. He remembered hearing the music and now, idiotically, he could suddenly identify the tune he had heard. ‘The Downfall of Paris’. By now the bandsmen should be doing their other job, of caring for the wounded, but he could see none. ‘Bandsmen!’

Miraculously Lieutenant Price appeared, pale and unsteady, and with him a small group of the Light Company. ‘Sir?’

‘A stretcher. Fast! And send someone back to battalion.’

Price saluted. He had forgotten the drawn sword in his hand so that the blade, a curved sabre, nearly sliced into Private Peters. ‘Sir.’ The small group ran back.

Lawford was unconscious. Harper was binding the chest, his huge fingers astonishingly gentle with the tattered flesh. He looked up at Sharpe. ‘Take the arm off, sir.’

‘What?’

‘Better now than later, sir.’ The Sergeant pointed at the Colonel’s left arm, held by a single, glistening shred of tissue. ‘He might live, sir, so he might, but the arm will have to go.’

A splintered piece of bone protruded from the stump. The arm was bent unnaturally upwards, pointing towards the city, and Harper was binding the brief stump to stop the weakly pulsing blood. Sharpe picked his way to Lawford’s head, treading carefully for the ground was slick, though whether with blood or ice it was impossible to see. The only light came from the burning timber. He put the point of his sword down into the bloodied mess and Harper moved the blade till it was in the right place. ‘Leave the skin, sir. It’ll flap over.’

It was no different from butchering a pig or a bullock, but it felt different. He could hear crashes from the city, punctuating the screams. ‘Is that right?’ He could feel Harper manipulating the blade.

‘Now, sir. Straight down.’

Sharpe pushed down, with both hands, almost as if he was driving a stake into mud. Human flesh is resilient, proof against all but the hottest stroke, and Sharpe felt the gorge rise in his throat as the sword met resistance and he heaved down so that Lawford tipped in the scarlet slush and the Colonel’s lips grimaced. Then it was done, the arm free, and Sharpe stooped to the dead fingers and pulled off a gold ring. He would give it to Forrest to be sent home with the Colonel or, God forbid, to be sent to his relatives.

Lieutenant Price was back. ‘They’re coming, sir.’

‘Who?’

‘The Major, sir.’

‘A stretcher?’

Price nodded, looking sick. ‘Will he live, sir?’

‘How the hell do I know?’ It was not fair to vent his anger on Price. ‘What was he doing here anyway?’

Price shrugged miserably. ‘He said he was going to find you, sir.’

Sharpe stared down at the handsome Colonel and swore. Lawford had no business in the breach. The same, perhaps, could have been said of Sharpe and Harper, but the tall Rifleman saw a difference. Lawford had a future, hopes, a family to protect, ambitions that were within his grasp, and soldiering was not where those ambitions finally lay. They might all be thrown away for one mad moment in a breach, a moment to prove something. Sharpe and Harper had no such future, no such hopes, only the knowledge that they were soldiers, as good as their last battle, useful as long as they could fight. They were both, Sharpe thought, adventurers, gambling with their lives. He looked at the Colonel. It was such a waste.

Sharpe listened to the great noise coming from the city, a noise of rampage and victory. Once, perhaps, he thought, an adventurer had a future, back when the world was free and a sword was the passport to any hope. Not now. Everything was changing with a suddenness and pace that was bewildering. Three years before, when the army had defeated the French at Vimiero, it had been a small army, almost an intimate army, and the General could inspect all his troops in a single morning and have time to recognize them, remember them. Sharpe had known most officers in the line by face, if not by name, and was welcome at their evening fires. Not now. Now there were generals of this and generals of that, of division and brigade, and provost-marshals and senior chaplains, and the army was far too large to see on a single morning or even march on a single road. Wellington, perforce, had become remote. There were bureaucrats with the army, defenders of files, and soon, Sharpe knew, a man would be less important than the pieces of paper like that folded, forgotten gazette in Whitehall.

‘Sharpe!’ Major Forrest was shouting at him, waving, hurrying over the rubble. He was leading a small group of men, some of whom carried a door, Lawford’s stretcher. ‘What happened?’

Sharpe gestured at the ruin about them. ‘A mine, sir. He was caught by it.’

Forrest shook his head. ‘Oh God! What do we do?’ The question was not surprising from the Major. He was a kind man, a good man, but not a decisive man.

Captain Leroy, the loyalist American, leaned down to light his thin, black cigar from the flickering flames of the timber baulk. ‘Must be a hospital in town.’

Forrest nodded. ‘Into town.’ He stared in horror at the Colonel. ‘My God! He’s lost his arm!’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Will he live?’

Sharpe shrugged. ‘God knows, sir.’

It was suddenly freezing cold, the wind reaching over the breach to chill the men who rolled the Colonel, still mercifully unconscious, on to the makeshift stretcher. Sharpe wiped the sword blade on a scrap of Lawford’s cloak, sheathed it, and pulled the collar of his greatcoat high up his neck.

It was not the entry into Ciudad Rodrigo that he had imagined. It was one thing to fight through a breach, overcome the last obstacle, and feel the elation of victory, but to follow Lawford in a slow, almost funeral march was destroying the triumph. Inevitably, too, though Sharpe hated himself for thinking of it, there were other questions that hung on this moment.

There would be a new Colonel of the South Essex, a stranger. The Battalion would be changed, maybe for the better, but probably not for the betterment of Sharpe. Lawford, whose own future was seeping into the crude bandages, had learned to trust Sharpe years before; at Seringapatam, Assaye, and Gawilghur, but Sharpe could expect no favours from a new man. Lawford’s replacement would bring his own debts to be repaid, his own ideas, and the old ties of loyalty, friendship, and even gratitude that had held the Battalion together would be untied. Sharpe thought of the gazette. If it was refused, and the thought persisted that it might, then Lawford would have ignored the refusal. He would have kept Sharpe as Captain of the Light Company, come what may, but no longer. The new man would make his own dispositions and Sharpe felt the chill of uncertainty.

They pushed deeper into the town, through crowds of men intent on recompense for the night’s effort. A group of the 88th had hacked open a wine-shop, splintering the door with bayonets, and now had set up their own business selling the stolen wine. Some officers tried to restore order, but they were outnumbered and ignored. Bolts of cloth cascaded from an upper window, draping the narrow street in a grotesque parody of a holiday as soldiers destroyed what they did not want to loot. A Spaniard lay beside a door, blood trickling in a dozen spreading streams from his scalp, while in the house behind were screams, shouts, and the sobbing of women.

The main square was like a bedlam let loose. A soldier of the 45th reeled past Sharpe and waved a bottle in the Rifleman’s face. The man was hopelessly drunk. ‘The store! We opened the store.’ He fell down.

The French spirit store had been broken apart. Shouts came from the building’s interior, thumps as the casks were stove in, and musket shots as crazed men fought for the contents. A house nearby was in flames and a soldier, his red jacket decorated with the 45th’s green facings, staggered in agony, his back burning, and he tried to douse the flames by pouring a bottle over his shoulder. The spirit flared, scorched his hand, and the man fell, writhing, to die on the stones. Across the plaza a second house was burning and men shouted for help from its upper windows. On the pavement outside women screamed, pointing at their trapped men, but the women were scooped up by redcoats and carried shrieking into an alley. Nearby a shop was being looted. Loaves and hams were slung from the door, to be caught on outstretched bayonets, and Sharpe could see the flicker of flame deep inside the building.

Some troops had kept their discipline and followed their officers in futile attempts to stop the riot. One horseman rode at a group of drunks, and flailing down with a scabbarded sword, split the group apart, and rode out with a young girl, screaming, clinging to his saddle. The horseman took the girl to a growing huddle of women, sheltered by sober troops, and turned his horse back into the melee. Shrieks and screams, laughter and tears, the sound of victory.

Watching it all, in silent awe, the survivors of the French garrison had gathered in the centre of the plaza to surrender. They were mostly still armed, but submitted patiently to the British troops who systematically worked their way down the losers’ ranks and pillaged them. Some women clung to their French husbands or lovers, and those women were left alone. No one was taking revenge on the French. The fight had been short and there was little ill will. Sharpe had heard a suggestion, floating as a rumour before the assault, that all surviving Frenchmen were to be massacred, not as revenge, but as a warning to the garrison at Badajoz what to expect if they chose to resist in their larger fortress. It was no more than a rumour. These French, silent in the midst of rampage, would be marched into Portugal, over the winter roads to Oporto, and then back by ships to the foetid prison hulks or even the brand new prison, built for prisoners of war, in the bleakness of Dartmoor.

‘Good God.’ Major Forrest’s eyes widened as he stared at the rioting troops. ‘They’re animals! Just animals!’

Sharpe said nothing. There were few rewards for a soldier. The pay would make no man rich, and the battlefields that yielded booty were few and far between. A siege was the hardest fighting and soldiers had always regarded victory in a breach as reason for losing all discipline and taking their reward from the conquered fortress. And if the fortress was a city, so much the more loot, and if the inhabitants of the city were your allies, then that was bad luck; they were in the wrong place, at the wrong time. Life had always been like that, and always would, because this was ancient custom, soldiers’ custom. In truth Ciudad Rodrigo was not suffering much. There were, to Sharpe’s eyes, plenty of sober, disciplined troops who had not joined the riot and who would, by morning, have swept up the drunks, disposed of the corpses, and the city’s ordeal would soon end in alcoholic exhaustion. He looked round, trying to identify a hospital.

‘Sir! Sir!’ Sharpe turned. It was Robert Knowles, who had been his Lieutenant till the previous year, but was now a Captain himself. The ‘sir’ was pure habit. ‘How are you?’ Knowles smiled in delight. He wore the uniform of his new Regiment. Sharpe gestured at Lawford’s body and the young Captain’s face fell. ‘How?’

‘A mine.’

‘Christ! Will he live?’

‘God knows. We need a hospital.’

‘This way.’ Knowles had entered the town through the smaller breach, attacked by the Light Division, and he led the party north, through the crowds, and into a narrow street. ‘I passed it on the way here. A convent. Crauford’s there.’

‘Wounded?’ Sharpe had thought Black Bob Crauford to be indestructible. The General of the Light Division was the toughest man in the army.

Knowles nodded. ‘Shot. It’s bad. They don’t think he’ll live. There.’ He pointed to a big, stone building which was topped by a cross and fronted by an arched cloister lit by bracketed torches. Wounded men were lying outside, tended by friends, while screams came from the upper windows behind which the surgeons were already at work with their serrated blades.

‘Inside!’ Sharpe pushed through the men in the doorway, ignored a nun who tried to stop him, and forced a path for the Colonel’s stretcher. The tiled floor was gleaming with fresh blood that looked black in the candlelight. A second nun pushed Sharpe aside and looked down at Lawford. Her eyes saw the gold lace, the torn elegance of the blood-stained uniform, and she rapped orders at her sisters. The Colonel was carried through an arched doorway to whatever horrors the surgeons would inflict.

The small group of men looked at each other, saying nothing, but on each face there were deep lines of tiredness and sorrow. The South Essex, that had achieved so much under Lawford’s leadership, was about to change. Soldiers might belong to an army, wear the uniform of a Regiment, but they lived inside a battalion and the commander of the Battalion made or broke their happiness. Their thoughts were all the same.

‘What now?’ Forrest was weary.

‘You get some sleep, sir.’ Leroy spoke brutally.

‘Parade in the morning, sir?’ Sharpe suddenly realized that Forrest was in command until the new man was appointed. ‘The Brigade Major will have orders.’

Forrest nodded. He waved a hand towards the doorway where Lawford had disappeared. ‘I must report this.’

Knowles put a hand on Forrest’s elbow. ‘I know where the Headquarters will be, sir. I’ll take you.’

‘Yes.’ Forrest hesitated. He saw a severed hand lying on the checkered tiles and he nearly gagged. Sharpe kicked the hand out of sight beneath a dark wooden chest. ‘Go on, sir.’

Forrest, Leroy, and Knowles left. Sharpe turned to Lieutenant Price and Sergeant Harper. ‘Find the Company. Make sure they have billets.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Price seemed shocked. Sharpe tapped him on the chest.

‘Stay sober.’

The Lieutenant nodded, then pleaded. ‘Half sober?’

‘Sober.’

‘Come on, sir.’ Harper led Price away. There was no doubt about which man was in command.

Sharpe watched the men coming into the convent; the blinded, the lamed, the bleeding, French and British. He tried to blot the screaming from his ears, but it was impossible, the sound penetrated the senses like the acrid smoke that hung in the city’s streets this night. An officer of the 95th Rifles came down the main stairway, crying, and saw Sharpe. ‘He’s bad.’ He did not know who he was talking to, except that he saw in Sharpe another Rifleman.

‘Crauford?’

‘There’s a bullet in his spine. They can’t get it out. The bastard was standing in the middle of the breach, right in the bloody middle, and telling us to move our arses. They shot him!’