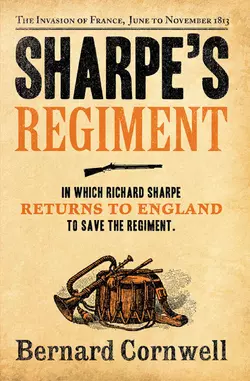

Sharpe’s Regiment: The Invasion of France, June to November 1813

Bernard Cornwell

Richard Sharpe returns to England to save the regiment.Major Sharpe’s men are in mortal danger – not from the French, but from the bureaucrats of Whitehall. Unless reinforcements can be brought from England, the regiment will be disbanded.Determined not to see his regiment die, Sharpe returns to England and uncovers a nest of high-ranking traitors, any of whom could utterly destroy his career with a word. Sharpe is forced into the most desperate gamble of his life – and not even the influence of the Prince Regent may be enough to save him.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.

SHARPE’S

REGIMENT

Richard Sharpe and the Invasion of France, June to November 1813

BERNARD CORNWELL

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Previously published in paperback by Fontana 1987

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1986

Copyright © Rifleman Productions Ltd 1986

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is a work of fiction.

The incidents and some of the characters portrayed in it, while based on real historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007298655

Ebook Edition © July 2009 ISBN: 9780007338719

Version: 2017-05-06

Sharpe’s Regiment is respectfully dedicated to the men of The Royal Green Jackets, Sharpe’s successors

‘The same combination of thorough research and narrative drive that distinguished its predecessors. It is a gripping read’

Independent

‘… if any ’prentices have severe masters, any children have undutiful parents, if any servants have too little wages, or any husband too much wife, let them repair to the noble Sergeant Kite, at the sign of the Raven in this good town of Shrewsbury, and they shall receive present relief and entertainment. Gentlemen, I don’t beat my drum here to ensnare or inveigle any man, for you must know, gentlemen, that I am a man of honour!’

From The Recruiting Sergeant by George Farquhar (1678–1707)

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u286c2176-71dd-5b53-aa09-1fe57cf29715)

Copyright (#u5828fd8f-e103-55f4-adf5-4c72c43e29ee)

Dedication (#u4aef27b4-4e1e-5669-a933-4995dfc4a61e)

Epigraph (#u998f8775-878e-567d-92c0-f3c063cd73ea)

Prologue: Spain June 1813 (#u4b5d4389-bd06-5823-83c1-5ce96dbda2be)

Prologue (#ud61990da-2f9d-5e48-8818-cff4ae58f63a)

Part One: England July – August 1813 (#ueb253b29-1cc4-5cb4-98f0-51cfcfec7593)

Chapter One (#u50444d84-654f-5cd2-9b3f-9f029fd7d030)

Chapter Two (#u2bfdbf9f-5845-5383-b018-28f734ae1778)

Chapter Three (#ud6d2eb0d-0735-5ef8-bdea-dd9b3aeb027a)

Chapter Four (#ue99c063a-9b53-5644-8b23-af756c4a7b42)

Chapter Five (#u30cf9aa8-8d06-5718-8219-2d7c18fc8dd0)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: France November 1813 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Sharpe’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in chronological order) (#litres_trial_promo)

The SHARPE Series (in order of publication) (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Bernard Cornwell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE

Regimental Sergeant Major MacLaird was a powerful man and the pressure of his fingers, where they gripped Major Richard Sharpe’s left hand, was painful. The RSM’s eyes opened slowly. ‘I’ll not cry, sir.’

‘No.’

‘They’ll not say they saw me cry, sir.’

‘No.’

A tear rolled down the side of the RSM’s face. His shako had fallen. It lay a foot from his head.

Sharpe, leaving his left hand in the Sergeant Major’s grip, gently pulled back the red jacket.

‘Our Father, which art in heaven.’ MacLaird’s voice choked suddenly. He lay on the hard flints of the roadway. Some of the dark flints were flecked with his blood. ‘Oh, Christ!’

Sharpe was staring into the ruin of the Sergeant Major’s belly. MacLaird’s filthy shirt had been driven into the wound that welled with gleaming, bright blood. Sharpe let the jacket fall gently onto the horror. There was nothing to be done.

‘Sir,’ the RSM’s voice was weak, ‘please sir?’ Sharpe was embarrassed. He knew what this hard man, who had bullied and whored and done his duty, wanted. Sharpe saw the struggle on the strong man’s face not to show weakness in death and he gripped MacLaird’s hand as if he could help this last moment of a soldier’s pride. MacLaird stared at the officer. ‘Sir?’

‘Our Father, which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name,’ the words came uncertainly to Sharpe’s lips. He did not know if he could remember the whole prayer. ‘Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.’ Sharpe had no belief, but perhaps when he died then he too would want the comfort of old phrases. ‘Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.’ One pound of twice-baked bread a day and it had been the bastard French who had trespassed. What were the next words? The flints dug into his knee where he knelt. ‘Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil, for Thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory, Amen.’ He thought he had remembered it all, but it did not matter now. MacLaird was dead, killed by a piece of stone the size of a bayonet that had been driven from a rock by the strike of a French cannon-ball. The blood had stopped flowing and there was no pulse in his neck.

Slowly Sharpe uncurled the fingers. He laid the hand on the breast, wiped the tears from the face, then stood. ‘Captain Thomas?’

‘Sir?’

‘RSM’s dead. Take him for burial. Captain d’Alembord!’

‘Sir?’

‘Push those picquets fifty yards further up the hill, this isn’t a god-damn field-training day! Move!’ The picquets were perfectly positioned, and everyone knew it, but Sharpe was venting an anger where he could.

The ground was wet, soaked by overnight rain. There were puddles on the track, some discoloured with blood. To Sharpe’s left, where the hillside fell away, a party of men hacked at the thin soil to make graves. Ten bodies, stripped of their jackets and boots that were too valuable to be buried, waited beside the shallow trench. ‘Lieutenant Andrews!’

‘Sir?’

‘Two Sergeants! Twenty men! Collect rocks!’

‘Rocks, sir?’

‘Do it!’ Sharpe turned and bellowed the order. In this mood men were foolish who crossed the tall, dark-haired officer who had risen from the ranks. His face, always savage, was tight with anger.

He walked to the sheltered place by the big rocks where the wounded were sheltered from wind’s knife-edge. Sharpe’s scabbard, which held the big, Heavy Cavalry blade that he wielded with the force of an axe, clanged on the ground as he crouched. ‘Dan?’

Daniel Hagman, Rifleman and ex-poacher, grinned at him. ‘I ain’t bad, sir.’ His left shoulder was bandaged, his jacket and shirt draped over the bound wound like cloaks. ‘I just can’t fill my pipe, sir.’

‘Here.’ Sharpe took the short clay stump, fished in Hagman’s ammunition pouch for the plug of dark, greasy tobacco, and bit a lump free that he crumbled and pushed into the bowl. ‘What happened?’

‘Bloody skirmisher. I thought the bastard was dead, sir.’ Hagman was the oldest man in the Battalion; perhaps he was over fifty, no one really knew. He was also the best marksman in the Regiment. He took the pipe from Sharpe and watched as the officer brought out a tinder-box. ‘I shot the bugger, sir. Went forward, and he cracks me. Bastard.’ He sucked on the pipe, blew smoke, and sucked again. ‘Angel got him. Knifed the bastard proper.’ He shook his head. ‘I’m sorry, sir.’

‘Don’t be a fool, Dan. Not your fault. You’ll be back.’

‘We beat the buggers, sir.’ Hagman, like Sharpe, was a Rifleman; one of a Company who, like flotsam in this ocean of war, had ended up in the red-jacketed ranks of the South Essex. Yet, out of cussedness and pride, they still wore their green jackets. They were Riflemen. They were the best. ‘We always beat the buggers, sir.’

‘Yes.’ Sharpe smiled, and the sardonic, mocking look that his face wore because of the scar on his left cheek suddenly disappeared. ‘We beat the bastards, Dan.’ They had, too. The South Essex, a Battalion under half its full strength, worn down by war the way a bayonet is thinned by use and sharpening, had beaten the bastards. Sharpe thought of Leroy, the American who had been the Battalion’s commanding officer. Leroy would have been proud of them today.

But Leroy was dead, killed last week at Vitoria, and soon, Sharpe knew, there would be a new Lieutenant Colonel, new officers, new men. Those new men were coming from England and Sharpe would give up his temporary command of this shrunken force that should not even have fought a battle this day.

They had been marching to Pasajes, ordered there in the wake of the great victory at Vitoria, when orders had come, brought on a sweating, galloped horse, that asked the South Essex to block this track from the mountains. The staff officer had not known what was happening, had only given a panicked account of a French force erupting from the frontier, and the South Essex, by chance, were closest to the threat. They had left their women and baggage on the main road and gone north to stop the French.

They succeeded. They had lined the track and their muskets had cracked in the deadly rhythm of platoon fire, flaying the northern approach, shredding the blue-jacketed enemy ranks.

The South Essex had not given ground. Their wounded had crawled to shelter or bled where they fell. Even when the enemy mountain gun had opened its fire, hurling back whole files in bloody shambles, they had not stepped back. They had fought the bastards to a standstill and seen them off, and now Major Richard Sharpe, the taste of tobacco still sour in his mouth, could see what price he had paid.

Eleven dead, and more would yet die of their wounds. At least twelve of the wounded would never return to the ranks. Another dozen, like Hagman, should live to fight again, unless their wounds turned filthy, and that fevered, slow death did not bear thinking about.

Sharpe spat. He had no water, for an enemy bullet had smashed his canteen open. ‘Sergeant Harper!’

‘Sir?’ The huge Irishman walked towards him. Perhaps alone in the Battalion this Rifleman would not fear Richard Sharpe’s anger, for Harper had fought beside Sharpe in every battle of this long war. They had marched the length of Spain until, in this summer of 1813, they were close to the French frontier itself. ‘How’s Dan, sir?’

‘He’ll live. Do you have any water?’

‘I did, but someone worked a miracle on it.’ Harper, who illicitly had red wine in his canteen, offered it to Sharpe. The Major drank, then pushed the cork home.

‘Thank you, Patrick.’

‘Plenty more if you need it, sir.’

‘Not for that. For being here.’ Harper had married just two days before and Sharpe had ordered the huge Irishman to stay with his new Spanish wife when the order to fight had come, but Harper had refused. Now Harper stared northwards at the empty horizon. ‘What were the buggers doing here?’

‘They were lost.’ Sharpe could think of no other explanation. He knew that a number of French units, cut off by the defeat of Joseph Bonaparte at Vitoria, were straggling back to France. This one had outnumbered Sharpe, and he had been puzzled why they had broken off the fight when they did. The only explanation he could find was that the enemy must have suddenly realised that the South Essex did not bar the way to France and thus there was no need to go on fighting. The French had been lost, they had blundered into a useless fight, and they had gone. ‘Bastards.’ Sharpe said it with anger, for his men had died for nothing.

Harper, who at six feet four inches, was taller even than Sharpe, frowned. ‘Terrible about the RSM, sir.’

‘Yes.’ Sharpe was looking at the sky, wondering whether more rain was coming. This summer had been the worst in Spanish memory. ‘You’ve got his job.’

‘Sir?’

‘You heard.’ Sharpe, while he commanded the Battalion, could at least give it the best Regimental Sergeant Major it would ever have. The new Colonel would be in no position to change the appointment. Sharpe turned away. ‘Lieutenant Andrews!’

‘Sir?’ The Lieutenant was leading a morose party of men who staggered under the weight of small boulders.

‘Put them on the graves!’ The stones would stop animals scrabbling down to the shallowly buried flesh.

‘All the graves, sir?’

‘Just ours.’ Sharpe did not care if the foxes and ravens gorged themselves on rotting French flesh, but his own men could lie in peace for whatever it was worth. ‘Sergeant Major?’

‘Sir?’ Harper was half grinning, half unsure whether a grin was acceptable at this moment. ‘Yes, sir?’

‘We’ll need a god-damned cart for our wounded. Ask a mounted officer to fetch one from the baggage. Then perhaps we can get on with this damned march.’

‘Yes, sir.’

That night rain fell on the pass where the South Essex had stood and suffered, and where their dead lay, and from which place the living had long gone. The night’s rain washed the scanty soil from the French dead who had not been buried but just covered with soil. The teeming water exposed white, hard flesh, and in the morning the scavengers came for the carrion. The pass had no name.

Pasajes was a port on the northern coast of Spain, close to where the shoreline bent north to France. It was a deep passage cleft in the rocks, leading to a safe, sheltered harbour that was crammed with shipping from Britain. The stores that fed Wellington’s army came to Pasajes now, no longer going to Lisbon to be carried by ox-carts over the mountains. At Pasajes the army gathered the stores that would let it invade France, but the South Essex who, even before the fight in the nameless pass had been considered too shrunken by war to take its place in the battle line, had been ordered to Pasajes instead. Their job, until their reinforcements arrived, was to guard the wharves and warehouses against thieves. They were fighting soldiers, and they had become Charlies, watchmen.

‘Bloody country. Bloody stench. Bloody people.’ Major General Nairn punctuated each remark by tossing an orange out of the window. He paused, waiting hopefully for a cry of pain or protest from beneath, but there was only the sound of the fruit thumping onto the cobbles. ‘You must be bloody disappointed, Sharpe.’

Sharpe shrugged. He knew that Nairn referred to the task of guarding the storehouses. ‘Someone has to do it, sir.’

Nairn scoffed at Sharpe’s meekness. ‘All you can do here is stop the bloody Spanish from pissing in our broth. I’m disappointed for you!’ He lumbered to his feet and crossed to the window. He watched two high-booted Spanish Customs officers slowly pace the wharves. ‘You know what those bastards are doing to us?’

‘No, sir.’

‘We liberate their bloody country and now they want to charge us bloody Customs duty on every barrel of powder we bring to Spain! It’s like saving a man’s wife from rape, then being asked to pay for the privilege! Foreigners! God knows why God made foreigners. They aren’t any bloody use to anyone.’ He glared at the two Customs men, debating whether to shy his last orange at them, then turned back to Sharpe. ‘What’s your strength?’

‘Two hundred and thirty-four effectives. Ninety-six in various hospitals.’

‘Jesus!’ Nairn stared incredulously at Sharpe. He had first met the Rifleman at Christmas and the two men had liked each other from the first. Now Nairn had ridden to Pasajes from the army headquarters in search of Sharpe. The Major General grunted and went back to his chair. He had white, straggly eyebrows that grew startlingly upwards to meet his shock of white hair. ‘Two hundred and thirty-four effectives?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘I suppose you lost some the other day?’

‘A good few.’ Three more men had already died of the wounds they received in the pass. ‘But we’ve got replacements coming.’

Major General Nairn closed his eyes. ‘He’s got replacements coming. From where, pray?’

‘From the Second Battalion, sir.’ The South Essex, for much of the war, had only possessed one Battalion, but now, in their English depot at Chelmsford, a second Battalion had been raised. Most regiments had two Battalions, the first to do the fighting, the second to recruit men, train them, then send them as needed to the First Battalion.

Nairn opened his eyes. ‘You have a problem, that’s what you’ve got. You know how to deal with problems?’

‘Sir?’ Sharpe felt the fear of uncertainty.

‘You dilute them with alcohol, that’s what you do. Thank God I stole some of the Peer’s brandy. Here, man.’ Nairn had pulled the bottle from his sabretache and poured generous tots into two dirty glasses he found on the table. ‘Tell me about your bloody replacements.’

There was not much to tell. Lieutenant Colonel Leroy, before he died, had conducted a lively correspondence with the Chelmsford depot. The letters from England, during the previous winter, told of eight recruiting parties on the roads, of crowded barracks and enthusiastic training. Nairn listened. ‘You asked for men to be sent?’

‘Of course!’

‘So where are they?’

Sharpe shrugged. He had been wondering exactly that, and had been consoling himself that the replacements could easily have been entangled in the chaos that had resulted from moving the army’s supply base from Lisbon to Pasajes. The new men could be at Lisbon, or at sea, or marching through Spain, or, worst of all, still waiting in England. ‘We asked for them in February. It’s June now; they must be coming.’

‘They’ve been saying that about Christ for eighteen hundred years,’ Nairn grunted. ‘You heard for certain they were being sent?’

‘No,’ Sharpe shrugged. ‘But they have to be!’

Nairn stared into his brandy as though it was a fortuneteller’s bauble. ‘Tell me, Sharpe, have you ever heard of a man called Lord Fenner? Lord Simon Fenner?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Bastard politician, Sharpe. Bloody bastard politician. I’ve always hated politicians. One moment they’re grovelling all over you, tongues hanging out, wanting your vote, the next minute they’re too bloody pompous to even see you. Insolent bastard jackanapes! Hate them! Hope you hate politicians, Sharpe. Not fit to lick your jakes out.’

‘Lord Fenner, sir?’ Sharpe knew bad news was coming. He knew that Major Generals, however friendly, did not ride long distances to share brandy with Majors.

‘Foul little pompous bastard, he is.’ Nairn spat the insult out. ‘Secretary of State at War, works to the Secretary of State of War, and probably neither would know what a war was even if it stuck itself in their back passages. So he wrote to us.’ Nairn took a piece of paper from his sabretache. ‘Or rather one of his poxed clerks wrote to us.’ He was staring at Sharpe rather than the letter. ‘He claims, Sharpe, that there are no reinforcements available to the South Essex. That none have been sent, and none are going to be sent. None. There.’ He handed the letter to Sharpe.

Sharpe could not believe it. He took the letter, fearing it, to find that it was a long list, sent by the War Office via the Horse Guards, of the replacements that could be expected in the next few weeks. At the end of the list was the South Essex, against whose name was written; ‘2nd Batt now Hold’g Batt. No Draft available.’ That was all and, if it was true, it meant that the South Essex’s Second Battalion had become a mere Holding Battalion; a place where boys of thirteen and fourteen, too young to fight, waited for their birthdays, or where men in transit or wounded men were put to wait for new postings. A rag-tag Battalion, without pride and of small purpose.

‘It can’t be true! There are recruits! We had eight recruiting parties!’

Nairn grunted. ‘In a covering letter, Sharpe, dictated by His bloody Lordship himself, but which I won’t offend you by showing to you, he recommends that your Battalion be broken up.’

For a few seconds Sharpe thought he had misheard Nairn. A Spanish muleteer shouted outside the window, from the harbour came the cranking sound of a windlass, and in Sharpe’s head echoed the words ‘broken up’.

‘Broken up, sir?’ Sharpe felt a chill in this warm room.

‘Lord Fenner suggests, Sharpe, that your men be given to other Battalions, that your Colours be sent home, that your officers either exchange into other regiments, sell their commissions, or make themselves available for our disposal.’

Sharpe was incredulous. ‘They can’t do it!’

Nairn gave a sour laugh. ‘Sharpe! They’re politicians! You can’t expect sense from the bastards!’ He leaned forward. ‘We’re going to need all the experienced units we can scrape together; all of them, but don’t expect Lord Fenner to understand that! He’s the Secretary of State at War and he wouldn’t know a bayonet from a ramrod. He’s a civilian! He controls the army’s money, which is why there isn’t any.’

Sharpe said nothing. He was thinking of the Battalion’s Colours laid up in some English church, hanging high in a dusty chancel while the men who had fought for them were scattered in penny-packets around the army. He was feeling anger, bitter anger, that his men, who had fought for those flags, who had suffered, whose comrades were in unmarked graves on a dozen battlefields would be broken up, disbanded. He was thinking of a Battalion that, like a family, had its quarrels and laughter, its warmth and pride, all to be sacrificed!

‘Breaking you up.’ Nairn said it brutally. ‘Bloody shame. Busaco, Talavera, Fuentes d’Onoro, Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, Salamanca, Vitoria, hell of a way to finish! Like sending a pack of hounds to the shambles, eh?’

‘But we had eight recruiting sergeants out!’

‘It’s no good telling me, Sharpe, I’m just a dogsbody.’ Nairn sniffed. ‘And even if we make you into a provisional Battalion you’ll go on losing men. You need a draft of replacements!’ It was true. If the South Essex was joined to another Battalion they would still take casualties, until the joint Battalion was shrunken and diluted again. Instead of being broken up, the South Essex would simply wither and die, its Colours forgotten, its morale wasted.

‘No!’ Sharpe almost howled the word in agonised protest. ‘They can’t do it!’

‘Let us hope not,’ Nairn smiled. ‘The Peer is not happy. He is damned crusty about it, Sharpe.’ Nairn spoke of Wellington. ‘He has this strange idea that the South Essex could be useful to him in France.’ The compliment was truthful. A veteran Battalion like the South Essex, even if its ranks were half-filled with raw replacements, had a morale and knowledge that doubled its fighting value. The South Essex had become a killing machine that could be guaranteed to face anything the French threw against it, while a fresh Battalion, however well trained in England, could take months to reach the same efficiency. Nairn splashed more brandy into the two glasses. ‘The Peer, Sharpe, does not trust those bastards in London. War Office! Horse Guards! Foreign Office! Ordnance Department! We’ve got more damned offices running this damned war than we’ve got Battalions! They’ve made a mess of it, they’ve lost their paperwork, they’ve got their breeches round their ankles and they can’t find mother to pull them up. Who’s in charge at Chelmsford?’

Sharpe had to think. His brain was in a turmoil of anger and astonishment that his Battalion could be broken up! ‘In Chelmsford, sir? Man called Girdwood. Lieutenant Colonel Girdwood.’

‘Ever met him?’

‘Never set eyes on him.’

‘He’s got men! He just doesn’t want to lose them! Happens all the time, Sharpe! Man has a Second Battalion, trains them, makes them into toy soldiers, and he can’t bear sending them abroad where the First Battalion will make them dirty! So go and see this Girdwood.’ Nairn said the name with mocking relish. ‘Persuade Girdwood to give you some men from this so-called Holding Battalion! Lick Girdwood’s boots! Get Girdwood drunk! Offer to pleasure Girdwood’s wife! You’ll find some men in Chelmsford!’ Nairn laughed at Sharpe’s expression, then tossed a sealed packet of orders to him. ‘Authorisation for you and three others to go to England to select replacements. Be back by October. That gives you nearly four months.’

Sharpe stared at the Scotsman. ‘Go to England?’

‘I know it’s a grim thought, Sharpe,’ Nairn grinned, ‘but nothing’s going to happen here, nothing! Boody politicians won’t let us invade France until Prussia makes up its mind whether to join the dance again. All we’re going to do is take San Sebastian and Pamplona then sit on our backsides doing nothing! You might as well go home, you’ll miss nothing. Go to Chelmsford.’

‘I can’t go home!’ He meant he could not leave his men.

‘You bloody well have to! You want the South Essex to die? You want to be a storekeeper?’ Nairn drank his brandy. ‘The Peer doesn’t want to break you up. He’ll make you into a Provisional Battalion if he must, but he’d rather you brought yourself up to strength. Go to Chelmsford, find men! If there are none there, then find other men!’

‘And if there aren’t any men?’

The Scotsman drew his finger across his throat. ‘Death of a regiment. Damned shame.’

And now of all times? Now, when the army gathered its strength at the edge of Napoleon’s heartland, on the border of France? Soon, perhaps this autumn or next spring, the men who had first landed at Lisbon would march into France and the South Essex should march with them. They had earned that privilege. On the day when the enemy’s empire was finally brought down, the flags of the South Essex should be flying in victory. Sharpe gestured at Lord Fenner’s letter. ‘How do I oppose that?’

Nairn shook his head. ‘It’s a mistake, Sharpe! Has to be! But you can’t put mistakes right by sending letters! We’ve written to the useless bastards, but letters to the Horse Guards are put in a drawer marked Urgent Business to be Ignored. But they can’t ignore you. You’re a hero!’ He said it with friendly mockery. ‘Go to Chelmsford, find your men, and bring them back. It will take half the time of doing it by letter.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Sharpe sounded dazed. Go to England?

‘And bring me back some whisky, that is a direct order! There’s a shop on Cornhill that gets the stuff from Scotland.’

‘Yes, sir.’ Sharpe spoke distractedly. Going home? England? He did not want to go, but if the alternative was to watch a Battalion die that had earned its right to tramp the roads of France, then he would go through hell itself. For his Regiment, and for its Colours that had flown through the cannon smoke of half a continent, he would go to England so that he could march into France. He would go home.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

Sharpe, arriving in Chelmsford, could not remember the way to the South Essex’s depot. He had only visited the barracks once, a brief visit in ’09, and he was forced to ask directions from a vicar who was watering his horse at a public trough. The vicar looked askance at Sharpe’s unkempt uniform, then thought of a happy explanation for the soldier’s vagabond appearance. ‘You’re back from Spain?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well done! Well done! First class!’ The vicar pointed eastwards, directing the soldiers out into the open country. ‘And God bless you!’

The four men walked eastwards. Sharpe and Harper earned odd glances, just as they had in London, for they looked as if they had come straight from a Spanish battlefield and still expected, even in this county town’s quiet streets, to meet a French patrol. Captain d’Alembord was dressed more elegantly than Sharpe or Harper, yet even his uniform, like Lieutenant Price’s, showed the ravages of battle. ‘It ought to work wonders with the ladies.’ D’Alembord fingered a rent in his scarlet jacket, made by a French bayonet at Vitoria.

‘Speaking of which,’ Lieutenant Harry Price had drawn his sword as they left the town behind and now slashed with the blade at the cow-parsley that grew thick in the lane, ‘are you going to give us some leave, sir?’

‘You don’t want leave, Harry. You’ll only get into trouble.’

‘All those girls in London!’ Price said wistfully. ‘Most of them haven’t met a hero like me! Back from the wars and what are you smiling at, Sergeant?’

Harper grinned broadly. ‘Just having a grand day, sir.’

Sharpe laughed. He was beginning to think that this journey was entirely unnecessary. He was convinced now that Lord Fenner’s letter was a mistake, and that there were, indeed, replacements waiting in Chelmsford. In London Sharpe had visited the Horse Guards, reporting his presence to the authorities, and the clerk in the dusty, impatient office had confirmed that the Second Battalion was indeed at Chelmsford. The man could offer no explanation as to why it was now called a Holding Battalion, suggesting wearily to Sharpe that it was, perhaps, merely an administrative convenience, but he could confirm that it was drawing rations and pay for seven hundred men.

Seven hundred! That figure gave Sharpe hope. He was certain now that the First Battalion was saved, that within weeks, even days, he would lead the replacements south to Pasajes. He walked towards the barracks with high hopes, his optimism made yet more buoyant by the splendour of this summer countryside.

It seemed like a dream. Sharpe knew that England was as heavy with beggars and slums and horror as any city in Spain, yet after the plains of Leon or the mountains of Galicia, this landscape seemed like a foretaste of heaven.

They walked through an England heavy with food and soft with foliage, a country of ponds and rivers and streams and lakes. A country of pink-cheeked women and fat men, of children who were not wary of soldiers or strangers. It was unnatural to see chickens pecking the road-verges undisturbed, their necks not wrung by soldiers; to see cows and sheep that were in no danger from the Commissary officers, to see barns unguarded, and cottage doors and windows not broken apart for firewood, nor marked with the chalk hieroglyphs of the billeting sergeants. Sharpe still found himself judging every hill, every wood, every turn in the road as a place to fight. That hedgerow, with its sunken lane behind, would be a deathtrap to cavalry, while an open meadow, bright with buttercups and rising towards a fat farm on a gentle hill, would be a place to avoid like the plague if French cuirassiers were in the area. England seemed to Sharpe to be a plump country, lavish and soft. Yet if he found it strange it was nothing to the reaction of Harper’s wife.

Harper had asked that Isabella should come with them. She was pregnant, and the big Irishman did not want her following the army into strange, hostile France. He had a cousin who lived in Southwark, and there Isabella had been deposited until the war should end. ‘A man doesn’t need his wife on his coat-tails,’ Harper had declared with all the authority of a man married less than a month.

‘You didn’t mind her there before you were married,’ Sharpe had said.

‘That’s different!’ Harper said indignantly. ‘The army’s no place for a married woman, nor is it.’

‘Will she be happy in England?’ Sharpe asked.

‘Of course she’ll be happy!’ Harper was astonished at the question. Happiness to him was being alive and fed, and the thought that Isabella might be fearful of life in a strange country did not seem to have occurred to him.

And, to Isabella, England seemed most strange. On the journey from Portsmouth to London she had shyly whispered questions to her husband. Where were the olive trees? Were there no oranges? No vines? No Catholic churches? She could not believe how full and plentiful were the rivers, how carelessly the villagers spilt water, how green, thick and tangled was the vegetation, how fat were the cows.

And even three days later, walking out of Chelmsford, it still seemed unreal to Sharpe that a country could be so plump. They passed ripening orchards, grain fields bright with poppies, and pigs running free that could have fed an army corps for a week. The sun shone, the land was warmed and fragrant, and Sharpe felt the careless joy of a man who knew that a task he had thought difficult or even impossible was suddenly proving so simple.

His optimism was dashed at the barracks. It was dashed as suddenly as if Napoleon’s Imperial Guard had appeared in Chelmsford’s marketplace. He had come here in hope, expecting to find seven hundred men, and the depot seemed deserted.

There was not even a guard on the gate. The wind stirred the dust, weeds grew between the paving stones, and a door creaked back and forth on ungreased hinges. ‘Guard!’ Sharpe’s voice bellowed angrily and was met by silence.

The four soldiers walked into the archway’s shadow. The depot was not entirely abandoned for, on the far side of the wide parade ground, a file of cavalrymen walked their horses. Sharpe pushed open the creaking door and looked into an empty guardroom. For a few seconds he wondered if the Battalion had been shipped to Spain, if somewhere on the wind-fretted ocean he had crossed their path on this useless mission, but surely the Horse Guards would have known if the Battalion had moved?

‘Someone’s home,’ d’Alembord said. He nodded towards the Union flag that stirred weakly from a flagpole in front of an elegant, brick-built building which, Sharpe remembered, housed the officers’ Mess and the regiment’s offices. Beside the flagpole, its shafts empty, stood an open carriage.

Harper pulled his shako over his forehead. ‘What in hell’s name are cavalry doing here?’

‘Christ knows.’ Sharpe’s voice was grim. ‘Dally?’

‘Sir?’ D’Alembord was brushing the dust from his boots.

‘Take the Sergeant Major. Go round this place and roust the bastards out.’

‘If there’s anyone to roust out,’ d’Alembord said gloomily.

‘Harry! With me.’

Sharpe and Price walked towards the headquarters building. Sharpe’s face, Price saw, boded ill for whoever had left the guardroom empty and the depot unguarded.

Sharpe climbed the steps of the elegant house and, as at the main gate, there was no sentry at the door. He led Price into a long, cool hallway that was hung with pictures of red-coated men in battle array. From somewhere in the house came the tinkle of music and the sound of laughter.

Sharpe opened a white-painted door to find an empty office. A fly buzzed at the unwashed window above the dead bodies of other flies. The papers on the desk were thick with dust. A small, black-cased clock on the mantel had stopped with both its hands hanging down to the six.

Sharpe pushed open a second door on the far side of the hall. He stared into an elegantly appointed dining room, empty as the office, with a great, varnished table on which stood silver statuettes. A half-empty decanter of wine held a slowly drowning wasp. Sharpe closed the door.

The hallway was carpeted, its furniture heavy and expensive, and its paintings new. Above a curving staircase was a huge chandelier, its gilded brackets thick with wax. Sharpe put his shako on a table and frowned as the laughter swelled. He heard a girl’s voice distinct above the trilling of the spinet. Lieutenant Price grinned at the sound. ‘Sounds like a brothel, sir.’

‘It does, too.’ Sharpe’s voice hid the anger that was thick in him, an anger at an unguarded barracks where women’s laughter mingled with tinkling music.

He went to the last door in the hallway, the one that he remembered opened into the Mess and from which came the laughter. He pushed the door slowly open, stood in the dark shadows of the hallway, and watched.

Three officers, all wearing the yellow facings and chained-eagle badge of the South Essex, were in the room. Two girls were with them, one sitting at the spinet, the other blindfolded in the centre of the room.

They were playing blind-man’s bluff.

The officers laughed, they dodged the lunges of the blind-folded girl. One of them stood guard so that she should not stumble into a low table that carried a tea of thin sandwiches, small pastries, and delicate porcelain cups. That officer, a Captain, was the first to see Sharpe.

The Captain made a mistake. It was a common enough error. In Spain men often mistook Sharpe for a private soldier for the Rifleman wore no badges of rank on his shoulders, and his red, whip-tasselled officer’s sash had long been lost. He wore an officer’s weapon, a sword, but in the hall’s shadow the Captain did not see it. He only saw the rifle on Sharpe’s shoulder and he assumed, naturally enough, that only a private would carry a long-arm. Harry Price, whose uniform was more conventional, was hidden behind Sharpe.

The Captain frowned. He was a young man with a sharp-featured, thin-lipped face beneath carefully waved blond hair. The smile he had worn for the game was suddenly replaced by irritation. ‘Who the devil are you?’ His voice was confident, the voice of the young master in his little domain, and it stopped the blindfolded girl in her tracks.

The other two officers were Lieutenants. One of them frowned at Sharpe. ‘Go away! Wrong place! Go!’

The other Lieutenant giggled. ‘About-turn! Quick march! One-two, one-two!’ He thought he had made a fine joke and laughed again. The girl at the spinet laughed with him.

‘Who are you? Well? Speak up, man!’ The Captain’s voice snapped petulantly at Sharpe, then suddenly died away as the Rifleman stepped out of the shadows.

The realisation that they might have made a mistake came to all three young officers at the same moment. They were suddenly silent and scared as they saw a tall man, black haired, with a face darkened by a foreign sun and scarred by a foreign blade, a strong face that was given a mocking look by the scarred left cheek. That mocking expression vanished when Sharpe smiled, but he was not smiling as he stalked into the Mess. He might have worn no badges of rank, but there was something about his face, about the sword at his side and about the battered hilt of the rifle slung on his shoulder that spoke of something far beyond their understanding. The girl in the room’s centre took off her blindfold and gasped at Sharpe’s sudden, startling appearance.

The room was well lit by tall southern windows. The carpet was thick. Sharpe came slowly forward and the Captain put his feet together as if at attention and stared at the faded jacket and tried to convince himself that the dark stains on the green cloth were not blood.

Harry Price, seeing that one of the two girls was pretty, leaned nonchalantly against the door jamb with what he considered a suitably heroic expression. Sharpe stopped. ‘Whose carriage is outside?’

No one spoke, but one of the girls made a hesitant gesture towards her companion. Sharpe turned. ‘Harry?’

‘Sir?’

‘You will arrange for the coach outside to be harnessed.’ He looked at the two girls. ‘Ladies. What is about to happen here is not for your ears or eyes. You will oblige me by going to your carriage with Lieutenant Price.’

Price, delighted with the orders, bowed to the girls, while one of the two Lieutenants, the young man who had laughed at his own jest and who looked hardly more than seventeen, frowned. ‘I say, sir …’

‘Quiet!’ It was a voice that sent orders across the chaos of battlefields and the snap of it made the girls squeal and stunned the three officers into shocked silence. Sharpe looked again at the girls. ‘Ladies? You will please leave.’

They fled, snatching scarves and reticules, abandoning music sheets, uneaten cakes, cups of tea, and a bowl of chocolate confections. Sharpe closed the door behind them.

He turned. He took the rifle from his shoulder and slammed it onto a varnished, delicate table. The sound made the three officers shiver. Sharpe looked at the Captain beside the spinet. ‘Who are you?’

‘Carline, sir.’

‘Who’s officer of the day?’

Carline swallowed nervously. ‘I am, sir.’

Sharpe looked at the Lieutenant who had told him to go away. ‘You?’

The Lieutenant forced his voice to sound unafraid. ‘Merrill, sir.’

‘And you?’

‘Pierce, sir.’

‘What Battalion are you?’ He looked back to Carline.

Carline, scarcely older than the two Lieutenants, tried to match the dignity of his higher rank with an unruffled face, but his voice came out as a frightened squeak. ‘South Essex, sir.’ He cleared his throat. ‘First Battalion.’

‘Who’s the senior officer in the depot?’

‘I am, sir,’ Carline said. He could not, Sharpe thought, have been more than twenty-two or three.

‘Where’s Lieutenant Colonel Girdwood?’

There was silence. A fly battered uselessly against a window. Sharpe repeated the question.

Captain Carline licked his lips. ‘Don’t know, sir.’

Sharpe walked to a massive sideboard that was heavy with decanters and ornaments. In the very centre of the display was a silver replica of a French Eagle which he picked up. On its base was a plaque. ‘This Memento of the French Eagle, Captured at Talavera by the South Essex under the Command of Colonel Sir Henry Simmerson, was Proudly Presented by Him to the Officers of the Regiment in Memory of the Gallant Feat.’ Sharpe grimaced. Sir Henry Simmerson had been relieved of the command before Sharpe and Harper had captured the Eagle. He turned to the three officers, the Eagle held in his hands as though it were a weapon. ‘My name is Major Richard Sharpe.’

Sharpe would have needed a soul of stone not to enjoy their reaction. They had been frightened of him from the moment he had walked from the hall shadows, but their fear was almost palpable now. A man they had thought a thousand miles away had come to this plump, soft, lavish place, and each of the three men felt a terrible, quivering fear. Pierce, who had laughed as he ordered Sharpe to about-turn, visibly shook. Sharpe let the fear settle into them before speaking in a low voice. ‘You’ve heard of me?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Carline answered.

These officers, Sharpe knew, were the rump of the First Battalion, the men who kept its home records and who were supposed to despatch replacements to Spain. Except there were no recruits, there were no replacements, because the depot was dead and empty, and its officers were entertaining young ladies. Sharpe looked at the two Lieutenants, seeing fleshy, spoilt faces above rich uniforms that, well cut though they were, could not hide the spreading waists and fat thighs. Merrill and Pierce, in turn, stared back at the tall, battle-hardened Rifleman as though he was a visitor from some strange, undiscovered island of savages.

Sharpe put the Eagle back on the sideboard. ‘Why was there no guard detail on the gate?’

‘Don’t know, sir.’ Carline, Sharpe saw, was wearing glossy dancing shoes buttoned over silk stockings.

‘What in Christ’s name do you mean? You’re officer of the day, aren’t you?’ The sudden loudness of Sharpe’s voice startled them.

‘Should have been, sir.’ Carline said it helplessly.

Sharpe looked through the window as the file of horsemen, dressed in fatigues, trotted past. ‘Who the hell are they?’

‘Militia, sir. They use the stables here.’

The three young men, standing rigidly at attention, watched Sharpe as he moved about the room, examining ornaments, picking up a newspaper, once pressing a key of the spinet and letting the plucked note die into ominous silence before he again spoke softly. ‘How many men of the First Battalion are here, Carline?’

‘Forty-eight, sir.’

‘Detail them!’

Carline did. There was himself, three Lieutenants, four sergeants, and the rest were all storekeepers or clerks. Sharpe’s face showed nothing, yet he was seething with frustration and anger within. Forty-eight men to revive a wounded First Battalion, and no sign of the Second Battalion!

He stopped by the window and looked at each man in turn. ‘You god-damn bloody astonish me! No guard mounted, but you’ve got time to play blind-man’s buff and have a little teaparty. What do you do when you exert yourselves, arrange flowers?’ All three kept a judicious, embarrassed silence, avoiding his eyes as he looked at them again in turn. ‘Starting at six this evening, and thereafter on the hour, every hour, day and night till I’m bored with you, you will report in full regimentals to Sergeant Major Harper, who, you will be glad to hear, has returned from Spain with me. You!’ Sharpe pointed at Merrill, whose face showed utter horror at the thought of parading in front of an inferior, ‘and you!’ The finger moved to Pierce. ‘You will find Captain d’Alembord outside. You will request him to parade the men and tell him I am making an inspection in ten minutes, and once I have done that I shall inspect the barracks. Move!’

They moved like hares out of a coursing trap, running out of the room, leaving Carline alone with Sharpe.

Sharpe ate a sandwich. He let the silence stretch. The walls of this comfortable room were bright with hunting pictures, red-coated horsemen in full cry across grass. Sharpe’s sudden question made Carline jump. ‘Where’s Lieutenant Colonel Girdwood?’

‘Don’t know, sir.’ Captain Carline now sounded plaintive, like a small boy hauled up in front of a fearsome headmaster.

Sharpe stared with distaste at the thin, petulant man. ‘Colonel Girdwood does command the Second Battalion?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘So where the hell is he? And where in Christ’s name is the Second Battalion?’

‘I don’t know, sir.’

Sharpe stepped close to him, close enough to smell the tea on Carline’s breath and the pomade in his carefully waved hair. ‘Captain.’ Sharpe, taller than Carline, looked down into the pale eyes and made his voice conversational. ‘You’ve heard men speak, presumably, of Regimental Sergeant Major MacLaird?’

Carline gave the smallest nod. ‘I’ve heard the name, sir.’

‘Less than one month ago, Carline, I saw his guts in blood. His belly was slit open. It was not a pretty sight, Captain. It would have spoilt your tea. But I’ll show it to you, Captain Carline. I’ll rip your bloody guts out with my own hands unless you answer me some god-damned questions! I’ll pull your spine out of your throat! You hear me?’

Carline looked as if he might faint. ‘Sir?’

‘Where is the Second Battalion?’

‘I don’t know, sir.’ He said it pleadingly, with naked fear in his eyes, and Sharpe believed him.

‘Then what the hell do you know, Captain Carline?’

Slowly, haltingly, Carline told his story. The Second Battalion, he said, had been stood down six months before, converted into a Holding Battalion. All recruiting had been stopped. Then, abruptly, the Second Battalion had marched away.

‘Just like that?’ Sharpe snarled the question. ‘They simply vanished?’

‘Yes, sir.’ Carline said it plaintively.

‘No explanations?’

Carline shrugged. ‘Colonel Girdwood said they were going to other units, sir.’ He paused. ‘He said the war’s coming to an end, sir, and the army was being pruned. We were to send our last draft out to the First Battalion and then just keep the depot tidy.’ He shrugged again, a gesture of helplessness.

‘The French are pruning the bloody army, Carline, and we need recruits! Are you recruiting for the First Battalion?’

‘No, sir. We were ordered not to!’

Sharpe saw Patrick Harper dressing a feeble Company into ranks on the parade ground. He turned back to Carline. ‘Colonel Girdwood said the men were being taken to other units?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Would it surprise you, Carline, to know that the Second Battalion still draws pay and rations for seven hundred men?’

Carline said nothing. He was doubtless thinking what Sharpe was thinking, that the seven hundred were non-existent and their pay was being appropriated by Lieutenant Colonel Girdwood. It was a scandal as old as the army; drawing the pay of men who did not exist. Sharpe, in a gesture of irritation, swatted a fly with his hand and ground it into the carpet with his boot. ‘So what do you do with the Second Battalion’s mail? Its paperwork? I presume some of it still comes here?’

‘We send it on to the War Office, sir.’

‘The War Office!’ Sharpe’s astonishment made his voice suddenly loud. The War Office was supposed to conduct war, and Sharpe would have expected the paperwork to go to the Horse Guards that administered the army.

‘To Lord Fenner’s secretary, sir.’ Carline spoke with more confidence, as if the mention of the politician’s name would awe Sharp.

It did. Lord Fenner, the Secretary of State at War, had suggested in his despatch to Wellington that the First Battalion be broken up and now, it seemed, he was the man responsible for the disappearance of the Second Battalion, a disappearance that must obviously have the highest official backing. Or else, and it seemed unthinkable, Lord Fenner was an accomplice with Lieutenant Colonel Girdwood in peculation; stealing money through a forged payroll.

Footsteps were loud in the hallway, and Patrick Harper loomed huge in the doorway of the Mess. He slammed to attention. ‘Men on parade, sir. What there are of them.’

Sharpe turned. ‘Regimental Sergeant Major Harper? This is Captain Carline.’

‘Sir!’ Harper looked at Carline rather as a tiger would look at a goat. Carline, in his dancing shoes and with one hand on the spinet, seemed incapable of speaking. To think of himself as a soldier in the presence of these two tall, implacable men was ridiculous.

‘Sergeant Major,’ Sharpe’s voice was conversational, ‘do you think the war has addled my wits?’

There was a flicker of temptation on the broad face, then a respectful, ‘No, sir!’

‘Then listen to this story, RSM. The South Essex raises a Second Battalion whose job is to find men, train men, then send them to our First Battalion in Spain. Is that correct, Captain Carline?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘So it recruits. It did recruit, Captain?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And six months ago, RSM,’ Sharpe swung back, ‘it is made into a Holding Battalion. No more recruiting, of course, it is merely a convenient dung heap for the army’s refuse.’ He stared at Carline. ‘No one knows why. We poor bastards are dying in Spain, but some clodpole decides we don’t need recruits.’ He looked back at Harper. ‘I am told, RSM, that the Holding Battalion has been broken up, it has disappeared, it has vanished! Its mail goes to the War Office, yet it still draws rations for seven hundred men. Sergeant Major Harper?’

‘Sir?’

‘What do you think of that story?’

Harper frowned. ‘It’s a real bastard, sir, so it is.’ He smiled. ‘Perhaps if we break some heads, sir, some bastards will stop lying.’

‘I like that thought, Sergeant Major.’ Sharpe stared at Carline, and his voice was conversational no longer. ‘If you’ve lied to me, Captain, I’ll tear you to tatters.’

‘I haven’t lied, sir.’

Sharpe believed him, but it made no difference. He was in a fog of deception, and the hopelessness of it made him furious as he went into the sunlight to inspect the few men who had been assembled by d’Alembord. Either there were no men in the Second Battalion, in which case there would be no trained replacements for the invasion of France, or, if they did exist, Sharpe would have to find them through Lord Fenner who would, doubtless, not take kindly to an interfering visit from a mere Major.

He stalked through the sleeping huts, wondering how he was to approach the Secretary of State at War, then went to inspect the armoury. The armoury sergeant, a veteran with one leg, was grinning hopefully at him. ‘You remember me, sir?’

Sharpe looked at the leathery, scarred face, and he cursed himself because he could not put a name to it, then Patrick Harper, standing behind him, laughed aloud. ‘Ted Carew!’

‘Carew!’ Sharpe said the name as if he had just remembered it himself. ‘Talavera?’

‘That’s right, sir. Lost the old peg there.’ Carew slapped his right leg that ended in a wooden stump. ‘Good to see you, sir!’

It was good to see Sergeant Carew for, alone in the Chelmsford depot, he knew his job and was doing it well. The weapons were cared for, the armoury tidy, the paperwork exact and depressing. Depressing because, when Lieutenant Colonel Girdwood had marched the Second Battalion away, the records revealed that he had left all their new weapons behind. Those brand-new muskets, greased and muzzlestoppered, were racked beneath oiled and scabbarded bayonets. That fact suggested that the men had been sent to other Battalions who could be expected to provide weapons from their own armouries. ‘He didn’t take any muskets?’ Sharpe asked.

‘Four hundred old ones, sir.’ Sergeant Carew turned the oil-stained pages of his ledger. ‘There, sir.’ He sniffed. ‘Didn’t take no new uniforms neither, sir.’

Non-existent men, Sharpe thought, needed neither weapons nor uniforms, but, just as he was deciding that this quest was hopeless because the Second Battalion had been broken up and scattered throughout the army, Sergeant Carew gave him sudden, extraordinary hope. ‘It’s a funny bloody thing, sir.’ The Sergeant lurched up and down on his wooden leg as he turned to look behind him, fearful that they would be overheard.

‘What’s funny?’

‘We was told, sir, that the Second’s just a holding Battalion. No more recruits? That’s what they said, sir, but three weeks ago, as I live and breathe, sir, I saw one of our parties with a clutch of recruits! Sergeant Havercamp, it was, Horatio Havercamp, and he was marching ’em this way. I said “hello”, I did, and he tells me to bugger off and mind my own business. Me!’ Carew stared indignantly at Sharpe. ‘So I talks to the Captain here and I asks him what’s happening? I mean the recruits never got here, sir, not a one of them. Haven’t seen a lad in six months!’

Sharpe stared at the Sergeant, and the import of what Carew was saying dawned slowly on him. Holding Battalions did not recruit. If there were recruits then there was a Second Battalion, and the seven hundred men did exist, and the Regiment could yet march into France. ‘You saw a recruiting party?’

‘With me own eyes, sir! I told the Captain too!’

‘What did he say?’

‘Told me I was drunk, sir. Told me there were no more recruiting parties, nothing! Told me I was imagining things, but I wasn’t drunk, sir, and sure as you’re standing there and me here I’m telling you I saw Horatio Havercamp with a party of recruits. Now why would they not come here, sir? Can you tell me that?’

‘No, Sergeant, I can’t.’ But he would find out, by God he would find out. ‘You’re certain of what you saw, Sergeant?’

‘I’m certain, sir.’

‘This Sergeant Havercamp wasn’t recruiting for another regiment?’

Carew laughed. ‘Wore our badge, sir! Drummer boys had your eagle on the drums. No, sir. Something funny happening, that’s what I think.’ He was stumping towards the door, his keys jangling on their iron ring. ‘But no one listens to me, sir, not any more. I mean I was a real soldier, sir, smelled the bloody guns, but they don’t want to know. Too high and bloody mighty.’ Carew swung the massive iron door shut, then turned again to make sure none of the depot officers were near. ‘I’ve been in the bloody army since I was a nipper, sir, and I know when things are wrong.’ He looked eagerly up at Sharpe. ‘Do you believe me, sir?’

‘Yes, Ted.’ Sharpe stood in the slanting evening light, and almost wished he did not believe the Sergeant, for, if Ted Carew was right, then a Battalion was not just missing, but deliberately hidden. He went to inspect the stables.

A missing Battalion? Hidden? It sounded to Sharpe like a madman’s fantasy, yet nothing in Chelmsford offered a rational explanation. By noon the next day Sharpe and d’Alembord had searched the paperwork of the depot and found nothing that told them where Lieutenant Colonel Girdwood had gone, or whether the Second Battalion truly existed. Yet Sharpe believed Carew. The Battalion did exist, it was recruiting still, and Sharpe knew he must return to London, though he dreaded the thought.

He dreaded it because he would have to seek an interview with Lord Fenner, and Sharpe did not feel at home among such exalted reaches of society. He suspected, too, that His Lordship would refuse to answer his questions, telling Sharpe, perhaps rightly, that it was none of his business.

Yet to have come this far to fail? He walked onto the parade ground and saw Carline, Merrill and Pierce standing indignantly to attention as Patrick Harper minutely inspected their uniforms. All three officers had shadowed, red-rimmed eyes because they had been up all night. Harper, used to broken nights of war, looked keen and fresh.

‘Halt!’ The sentry at the gate, eager to impress Major Sharpe, bellowed the challenge.

Sharpe turned.

A mounted officer appeared in the archway, glorious and splendid on a superb horse, dazzling in the red, blue and gold uniform of the 1st Life Guards, an officer utterly out of place in this remote, dull barracks square.

‘Bit hard to find, aren’t you?’ The officer laughed as he dismounted close to Sharpe. ‘It is Major Sharpe, yes?’

‘Yes.’

The Captain saluted. ‘Lord John Rossendale, sir! Honoured to meet you!’ Lord John was a tall young man, thin as a reed, with a humorous, handsome face and a lazy, friendly voice. ‘First time I’ve been here. I’m told there’s a decent little pack of hounds up the road?’ He pronounced the word hounds as ‘hinds’.

‘I wouldn’t know.’ Sharpe said it ungraciously. ‘You’re looking for me?’

‘Rather,’ Rossendale beamed happily. ‘Got something for you, sir. Or I did.’ He dug into his sabretache, failed to find whatever he had brought, clicked his fingers, cursed himself for foolishness, then, with a happy and enlightened burst of memory, found what he was looking for in his saddlebag. ‘There you are, sir! Safely delivered.’ He handed Sharpe a thick piece of folded paper, richly sealed. ‘Can I get luncheon here, sir? Your Mess does a decent bite, does it, or would you recommend the town?’

Sharpe did not answer. He had torn the paper open and was reading the ornate script. ‘Is this a joke?’

‘Lord, no!’ Lord John laughed anyway. ‘Bit of a privilege really, yes? He’s always wanted to meet you! He was happy as a drunken bat when the Horse Guards said you’d come home! We heard you’d died this summer, but here you are, eh? Fit as a fiddle? Splendid, eh? Should be quite jolly, really!’

‘Jolly?’

‘Rather!’ Lord John gave Sharpe his friendliest, most charming smile. ‘Best flummery and all that?’

‘Flummery?’

‘Uniform, sir. Get your chap to polish it all up, put on a bit of glitter, yes?’ He glanced at Sharpe’s jacket and laughed. ‘You can’t really wear that one, eh? They’d think you’d come to scour the chimneys.’ He laughed again to show he meant no offence.

Sharpe stared at the invitation, and knew that his luck had turned. A moment ago he had been apprehensive, rightly so, about seeing Lord Fenner, for what mere Major could demand answers of a Secretary of State at War? Now, suddenly, the answer had been delivered by this elegant, smiling messenger who had brought an invitation, a command, for Sharpe to go to London and there meet a man who, within the last year, had insisted that Sharpe was promoted, and a man whom even Lord Fenner dared not offend. The Prince of Wales, Prince Regent of England, demanded Major Richard Sharpe’s attendance at court, and Sharpe, if he was clever enough, would let that eminent Royal gentleman demand to know where the Second Battalion had been hidden. Sharpe laughed aloud. He would go over Lord Fenner’s head, and, with Royalty’s help, would march the Colours of his regiment into France.

CHAPTER TWO

‘There is a yellow line on the carpet. Observe it.’

‘Yes,’ said Major Richard Sharpe.

‘It is there that you stop.’ The chamberlain gave a small, fanciful gesture with his white-gloved fingers as if illustrating how to come to a halt. ‘You bow.’ Another curlicue of the fingers. ‘You answer briefly, addressing His Royal Highness as “Your Royal Highness”. You then bow again.’

Sharpe had been watching people approach the throne for ten tedious minutes. He doubted that, after seeing so many examples, he needed to be given such minute instructions, but the courtier insisted on saying it all again. Every elaborate gesture of the man’s white-gloved hand wafted perfume to Sharpe’s nose.

‘And when you have bowed the second time, Major, you back away. Do it slowly. You may cease the backward motion when you reach the lion’s tail.’ He pointed with his staff at the rampant lion embroidered onto the lavish red carpet. The courtier, with eyes that seemed to be made of ice, looked Sharpe up and down. ‘Some of our military gentlemen, Major Sharpe, become entangled with their swords during the backwards progression. Might I suggest you hold the scabbard away from your body?’

‘Thank you.’

A group of musicians, lavishly dressed in court uniform, with powdered wigs, plucked eyebrows, and intent, busy expressions, played violins, cellos, and flutes. The tunes meant nothing to Sharpe, not one of them a stirring, heart-thumping march that could take a man into battle. These tunes were frivolous and tinkling; mincing, delicate things suitable for a Royal Court. He felt foolish. He was grateful that none of his men could see him now; d’Alembord and Price were safely in Chelmsford, putting some snap into the half-deserted depot, while Harper, though in London, was with Isabella in Southwark.

Above Sharpe was a ceiling painted with supercilious gods who stared down with apparent boredom on the huge room. A great chandelier, its crystal drops breaking the candlelight into a million shards of light, hung at the room’s centre. A fire, an unnecessary luxury this warm night, burned in a vast grate, adding to an already overheated room that stank of women’s powder, sweat, and the cigar smoke that drifted in from the next chamber.

An Admiral was being presented. There was a spatter of light, bored applause from the courtiers who crowded about the dais. The Admiral bowed for a second time, backed away, and Sharpe saw how the man held his slim sword away from his body as he bobbingly reversed over the snarling lion.

‘Lord Pearson, your Royal Highness!’ said the overdressed flunkey who announced the names.

Lord Pearson, attired in court dress, strode confidently forward, bowed, and Sharpe felt his heart beating nervously when he thought that, in a few moments, he would have to follow the man up the long carpet. It was all nonsense, of course, ridiculous nonsense, but he was still nervous. He wished he was not here, he wished he was anywhere but in this stinking, overheated room. He watched Lord Pearson say his few words and thought, with a sense of doom, how impossible it would be to bring up the subject of the missing Battalion in those few, scaring seconds of conversation.

‘It is best,’ the courtier murmured in his ear, ‘to say as little as possible. “Yes, your Royal Highness” or “No, your Royal Highness” are both quite acceptable.’

‘Yes,’ Sharpe said.

There were fifty people being presented this evening. Most had brought their wives who laughed sycophantically whenever the courtiers on the dais laughed. None could hear the witticism that had provoked the laughter, but they laughed just the same.

The men were resplendent in uniform or court dress, their coats heavy with jewelled orders and bright sashes. Sharpe wore no decorations, unless the faded cloth badge that showed a wreath counted as a decoration. He had received that for going into a defended breach, being the first man to climb the broken, blood-slick stones at Badajoz, but it was a paltry thing beside the dazzling jewelled enamels of the great stars that shone from the other uniforms.

He had taken the wreath badge from his old jacket and insisted that the tailor sew it onto his brand-new uniform. It felt odd to be dressed so finely, his waist circled by a tasselled red sash and his shoulder-wings bright with the stars of his rank. Sharpe reckoned the evening had cost him fifty guineas already, most of it to the tailor who had despaired of making the new uniform in time. Sharpe had growled that he would go to the Royal Court in his old uniform and give the tailor’s name as the man responsible, and, as he had expected, the work had been done.

His uniform might be new, but Sharpe still wore his comfortable old boots. Sharpe had obstinately refused to spend money on the black leather shoes proper to his uniform, and the Royal Equerry who had greeted Sharpe in the Entrance Hall of Carlton House had frowned at the knee-high boots. Polish them as he might, Sharpe could not rid them of the scuff marks, or disguise the stitches that closed the rent slashed in the left boot by an enemy’s knife. The Equerry, whose own buckled shoes shone like a mirror, wondered whether Major Sharpe would like to borrow proper footwear.

‘What’s wrong with the boots?’ Sharpe had asked.

‘They’re not regulation issue, Major.’

‘They’re regulation issue to colonels of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard. I killed one of those bastards to get these boots, and I’m damned if I’m taking them off for you.’

The Equerry had sighed. ‘Very good, Major. If you so wish.’

By Sharpe’s side, in its battered scabbard, hung his cheap Heavy Cavalry sword. At Messrs Hopkinsons of St Albans Street, the army agents who were part bankers, part post office and part moneylenders to officers, he had a presentation sword from the Patriotic Fund, given to him as a reward for capturing the French Eagle at Talavera, but he felt uncomfortable with such a flimsy, over-decorated blade. He was a soldier, and he would come to this court with his own sword. But by God, he thought, he would rather be back in Spain. He would rather face a battalion of French veterans than face this ordeal.

‘A pace forward, Major?’

He obeyed, and the step took him closer to the edge of the crowd so that he could see better. He did not like what he saw; plump, self-satisfied people crammed into rich, elegant clothes. Their laughter tinkled as emptily as the music. Those who looked at Sharpe seemed to show a mixture of surprise and pity at his dowdiness, as though a bedraggled fighting cock had somehow found its way into a peacock’s pen.

The women were mostly dressed in white, their dresses tightly bound beneath their breasts to fall sheer to the carpet. Their necklines were low, their throats circled by stones and gold, their faces fanned by busy, delicate spreads of ivory and feathers. A woman standing next to Sharpe, craning to see over the shoulder of a man in front of her, showed a cleavage in which sweat trickled to make small channels through the powder on her breasts.

‘You had a good voyage, Major?’ the courtier asked in a tone which suggested he did not care one way or the other.

‘Yes, very good, thank you.’

‘Another pace forward, I think.’

He shuffled the obedient step. He was to be the last person presented to His Royal Highness. From another room in this huge house came a tinkle of glasses and a burst of laughter. The musicians still sawed at their instruments. The faces of the crowd that lined the long carpet glistened in the candlelight. Everyone, with the exception of Sharpe, wore white gloves, even the men. He knew no one here, while everyone else seemed to know everybody else, and he felt foolish and unwelcome. The air that he breathed seemed heavy, warm and damp, not with the humidity of a summer day, but with strong scent and sweat and powder that he thought would choke in his gullet.

A woman caught his eye and held it. For a second he thought she would smile at him to acknowledge the moment when their eyes locked, but she did not smile, nor look away, but instead she stared at him with an expression of disdainful curiosity. Sharpe had noticed her earlier, for in this overheated, crowded room she stood out like a jewel amongst offal. She was tall, slim, with dark red hair piled high above her thin, startling face. Her eyes were green, as green as Sharpe’s jacket, and they stared at him now with a kind of defiance.

Sharpe looked away from her. He was beginning to feel sullen and rebellious, angry at this charade, wondering what would happen to him if he simply turned and walked away from this place. But he was here for a purpose, to use the privilege of this presentation to ask a favour, and he told himself that he did this thing for the men who waited at Pasajes.

‘Remember, Major, to hold the sword away as you leave the presence.’ The courtier, a head shorter than Sharpe’s six foot, gave his delicate smile. ‘I shall see you afterwards, perhaps?’ He did not sound overjoyed at the prospect.

The moment had come. He was at the front of the crowd, facing the vast carpet, and he could see the eyes staring at him and then the overdressed servant at the foot of the dais looked at him and nodded.

He walked forward. Christ! he thought, but he would trip over or faint. His boots suddenly felt as heavy as pig-iron, his scabbard seemed to swing malevolently between his knees, then he frowned because, to his right, applause had begun and the applause grew and someone, a woman, shouted ‘bravo!’

He was blushing. The applause made him angrier. It was his own god-damned fault. He should have ignored the Royal command, but instead he was walking up this damned carpet, the faces were smiling at him and he was sure that he would become entangled with the huge sword that clanked in its metal scabbard by his side.

The woman who had stared at him, the woman with green eyes, watched him walk to the yellow line. She clapped politely, but without enthusiasm. A dangerous-looking man, she thought, and far more handsome than she expected. She had been told only that he came from the gutter, a bastard son of a peasant whore. ‘You won’t want to bed him, Anne.’ She remembered those words, and the mocking tone of the voice that spoke them. ‘Talk to him, though. Find out what he knows.’

‘Maybe he won’t want to talk to me.’

‘Don’t be a fool. A peasant like that will be flattered to speak to a lady.’

Now she watched the bastard son of a common whore bow, and it was plain that Major Richard Sharpe was not accustomed to bowing. She felt a small surge of excitement that surprised her.

The courtier waited for Sharpe’s clumsy bow to be made. ‘Major Richard Sharpe, your Royal Highness, attached to His Majesty’s South Essex Regiment!’

And the courtier’s words provoked more applause which the man sitting in the gilded, red-velvet cushioned throne encouraged by lightly tapping his white gloved fingers into his palm. No one else had received such applause, no one; and Sharpe blushed like a child as he stared into the glaucous eyes and fat face of the Prince of Wales, who, this night, was encased in the full uniform of a British general; a uniform that bulged on his thighs and over his full belly.

The applause died. The Prince of Wales seemed to gobble with delighted laughter. He stared at Sharpe as if the Rifleman was some delicious confection brought for his delight, then he spoke in a fruity, rich voice that was full of surprise. ‘You are dressed as a Rifleman, eh?’

‘Yes, your Majesty.’ Oh Christ, Sharpe thought. He should have called him ‘Your Royal Highness’.

‘But you’re with the South Essex, yes?’

‘Yes, your Royal Highness.’ Then Sharpe remembered that after the first answer he was supposed to call him ‘sir’. ‘Sir,’ he added.

‘Yes?’

Sharpe thought he was going to faint because the fat, middle-aged man was leaning forward in the belief that Sharpe wished to say something. Sharpe’s right hand fidgeted, wanting to cross his body and hold the sword handle. ‘Very honoured, your Majesty.’ Sharpe was sure he was going to faint. The room was a thick, indistinct whirl of powder, white faces, music and heat.

‘No, no, no, no! I’m honoured. Yes, indeed! The honour is entirely mine, Major Sharpe!’ The Prince of Wales snapped his fingers, smiled at Sharpe, and the small orchestra abruptly stopped playing the delicate melody that had accompanied Sharpe’s lonely walk up the carpet and, instead, started to play a military tune. The music was accompanied by gasps from the audience, gasps that were followed by more applause that grew and was swelled by cheers that forced the musicians to play even louder.

‘Look!’ The Prince of Wales gestured to Sharpe’s right. ‘Look!’

The clapping continued. Sharpe turned. A passage had been made in the applauding crowd and, through it, marching in the old-fashioned goose-step that Sharpe had not seen in nearly twenty years, were three soldiers in uniforms of such pristine perfection that they must have been sewn onto their upright bodies. They had old-fashioned powdered hair, high stocks, but it was not the three soldiers, impressive and impractical though they were, that had started the new applause.

‘Bravo!’ The shouts were louder as Sharpe stared at what the central soldier carried in his hands.

Sharpe had seen that object before, on a hot day in a valley filled with smoke and foul with the stench of roasting flesh. The wounded, he remembered, had been unable to escape the grass-fires and so they had burned where they lay on the battlefield, the flames exploding their ammunition pouches and spreading the fire further.

He had seen it before, but not like this. Tonight the staff was oiled and polished, and the gilt ornament shone in the candlelight. Before, on that hot day when the musket wads had burned and the wounded had screamed for Jesus or their mothers, Sharpe had held the battered, bloody staff, and he had scythed it like a halberd, cutting down the enemy, while beside him, screaming in his wild Irish tongue, Sergeant Harper had slaughtered the standard-bearers and Sharpe had taken this Eagle, this first French Eagle to be captured by His Majesty’s forces.

Now it was polished. About the base of the Eagle was a laurel wreath. It seemed unfitting. Once those proud eyes and hooked beak and half-spread wings had been on a battlefield, and it still belonged there, not here, not with these fat, sweating, applauding people who stared and smiled and nodded at him as the staff was thrust towards him.

‘Take it! Take it!’ the Prince Regent said.

Sharpe felt like a circus animal. He took it. He lowered the staff and he stared at the Eagle, no bigger than a dinner plate, and he saw the one bent wingtip where he had struck a man’s skull with the standard, and he felt oddly sorry for the Eagle. Like him it was out of place here. It belonged in the smoke of battle. The men who had defended it had been brave, they had fought as well as men could fight, and it was not right that these gloating fools should applaud this humbled trophy.

‘You must remind me of everything that happened! Just exactly!’ The Prince was struggling from the dais, coming towards Sharpe. ‘I insist on everything, everything! Over supper!’ To Sharpe’s horror the Prince, who, during his father’s madness, was the Regent and acting monarch of England, put an arm about his shoulders and led him across the carpet. ‘Every single small detail, Major Sharpe, in utter detail. To supper! Bring your bird! Oh yes, it’s not every day we heroes meet. Come! Come!’

Sharpe went to supper with a Prince.

There were twenty-eight courses in the supper, most of them lukewarm because the distance from the kitchens was so great. There was champagne, wine, and more champagne. The musicians still played.

The Prince of Wales was extraordinarily solicitous of Sharpe. He fed Sharpe’s plate with morsels, encouraged his stories, chided when he thought Sharpe was being modest, and finally asked the Rifleman why he had come to England.

Sharpe took a breath and told him. He felt a small moment of pleasure, for he was doing what he had come to do; saving a Regiment. He saw some frowns about the table when he spoke of the missing Battalion, as if the subject was unfitting for such an evening, but the Prince was delighted. ‘Some of my men are missing, eh? That won’t do? Is Fenner here? Fenner? Find Fenner!’ Sharpe suddenly felt that blaze of victory, like the moment in battle when the enemy’s rear ranks are going back and the front was about to crumple. Here, in the Chinese Dining Room of Carlton House, Sharpe had persuaded the Prince Regent himself to put the question which Sharpe himself had so dreaded taking to Lord Fenner. ‘Ah! Fenner!’

A courtier was conducting the Secretary of State at War towards the Prince’s table.