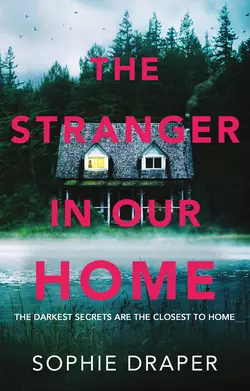

The Stranger in Our Home

Sophie Draper

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фольклор

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 577.47 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Have you been bad enough?When her stepmother dies unexpectedly, Caro returns to her childhood home in the rural English countryside. She hadn’t seen Elizabeth in years, but the remote farmhouse offers refuge from a bad relationship, and a chance to start again.But going through Elizabeth’s belongings unearths memories Caro would rather stay buried. In particular, the story her stepmother would tell her, about two little girls and the terrible thing they do.As heavy snow traps Caro in the village, where her neighbours stare and whisper, Caro is forced to question why Elizabeth hated her so much, and what she was hiding. But does she really want to uncover the truth?A haunting and twisty story about the lies we tell those closest to us, perfect for fans of Ruth Ware and Cass Green.Readers love THE STRANGER IN OUR HOME: ‘Spooky and absorbing. I was gripped from the first page’ CASS GREEN ‘A remarkably, taut and chilling debut. I absolutely loved it. Brilliant writing. All the creepiness. A heart-stopping ending’ CLAIRE ALLAN‘Sophie Draper is a remarkable new voice, combining beautiful writing with a gothic creepiness and a level of suspense which will keep the reader gripped to the end’ STEPHEN BOOTH′A brilliant, sinister debut that creeps under your skin and keeps you hooked until the shocking ending′ ROZ WATKINS‘Wow! This is what a horror story is supposed to be! Super spooky and absolutely wonderful in all its gothic glory’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER‘The ending was amazing. Psychological fiction at its best. Five Stars’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘I never use the term «jaw-dropping» but it best describes the rest of this spectacular read!’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘Stands up there near to of the top of the pile with narratives like «The Woman in the Window» and of course «The Girl on the Train».’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘The ending BLEW. ME. AWAY. I feel like I’m going to have a book hangover now. SO, SO GOOD’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER