Magpie

Sophie Draper

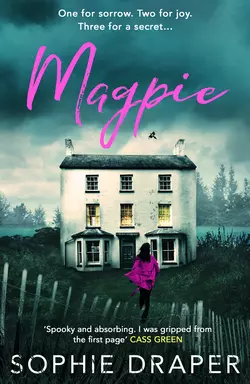

The dark, twisty new domestic suspense from the author of Cuckoo She’s married to him. But does she know him at all? Claire lives with her family in a beautiful house overlooking the water. But she feels as if she’s married to a stranger – one who is leading a double life. As soon as she can get their son Joe away from him, she’s determined to leave Duncan. But finding out the truth about Duncan’s secret life leads to consequences Claire never planned for. Now Joe is missing, and she’s struggling to piece together the events of the night that tore them all apart. Alone in an isolated cottage, hiding from Duncan, Claire tries to unravel the lies they’ve told each other, and themselves. Something happened to her family … But can she face the truth? Perfect for fans of Ruth Ware and C. J. Tudor ‘Chilling and heart-rending, a creepy, atmospheric story with a beautifully-drawn, bleak setting and memorably flawed characters’ Roz Watkins ‘Beautifully written, with a chilling mystery at its core, Magpie is a suspenseful and twisty pleasure of a read’ Howard Linskey ‘This eerie tale lingered with me for days after I’d read the final page. I didn’t see the final twist coming!’ Nicola Rayner ‘I could not stop reading this – creepy and compelling. I loved it’ Sarah Ward

MAGPIE

Sophie Draper

Copyright (#u1b424c42-aaad-583a-a9e1-bd4410cbe6e6)

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 2019

Copyright © Sophie Draper 2019

Cover design by Lisa Horton © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Stephen Mulcahey/Trevillion Images (house and woman); Silas Manhood/Arcangel Images (fence); Shutterstock.com (sky, magpie, water, grass)

Sophie Draper asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008311315

Ebook Edition © November 2019 ISBN: 9780008311322

Version: 2019-10-15

Dedication (#u1b424c42-aaad-583a-a9e1-bd4410cbe6e6)

For my boys.

Epigraph (#u1b424c42-aaad-583a-a9e1-bd4410cbe6e6)

One for sorrow,

Two for joy,

Three for a girl,

Four for a boy,

Five for silver,

Six for gold,

Seven for a secret,

Never to be told.

Contents

Cover (#ub42f6c43-73ec-5062-a08f-5eaff4594511)

Title Page (#u19ebf795-69a5-5a97-89d6-519137daa6ed)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1: Claire – Before

Chapter 2: Claire – Before

Chapter 3: Duncan – Six Weeks After

Chapter 4: Claire – Before

Chapter 5: Claire – After

Chapter 6: Claire – Before

Chapter 7: Claire – After

Chapter 8: Duncan – After

Chapter 9: Claire – Before

Chapter 10: Claire – Before

Chapter 11: Duncan – After

Chapter 12: Duncan – After

Chapter 13: Claire – Before

Chapter 14: Claire – Before

Chapter 15: Claire – After

Chapter 16: Duncan – After

Chapter 17: Claire – Before

Chapter 18: Claire – Before

Chapter 19: Claire – After

Chapter 20: Duncan – After

Chapter 21: Claire – After

Chapter 22: Duncan – After

Chapter 23: Claire – Before

Chapter 24: Claire – Before

Chapter 25: Claire – After

Chapter 26: Claire – After

Chapter 27: Claire – Before

Chapter 28: Claire – After

Chapter 29: Duncan – After

Chapter 30: Claire – After

Chapter 31: Claire – Before

Chapter 32: Claire – After

Chapter 33: Claire – Before

Chapter 34: Claire – Before

Chapter 35: Claire – After

Chapter 36: Duncan – After

Chapter 37: Claire – Before

Chapter 38: Claire – Before

Chapter 39: Claire – After

Chapter 40: Duncan – After

Chapter 41: Claire – Before

Chapter 42: Claire – After

Chapter 43: Claire – Before

Chapter 44: Claire – Before

Chapter 45: Claire – Before

Chapter 46: Duncan – After

Chapter 47: Claire – After

Chapter 48: Claire – After

Chapter 49: Claire – Before

Chapter 50: Duncan – After

Chapter 51: Claire – Before

Chapter 52: Claire – Before

Chapter 53: Claire – After

Chapter 54: Claire – Before

Chapter 55: Duncan – After

Chapter 56: Claire – Before

Chapter 57: Duncan – After

Chapter 58: Claire – After

Chapter 59: Claire – After

Chapter 60: Claire – After

Chapter 61: Duncan – 22 Years Before

Chapter 62: Duncan – After

Chapter 63: Claire – After

Chapter 64: Claire – After

Chapter 65: Duncan – After

Chapter 66: Duncan – After

Chapter 67: Claire – After

Chapter 68: Duncan – After

Chapter 69: Claire – After

Chapter 70: Claire – After

Chapter 71: Claire – After

Chapter 72: Duncan – After

Chapter 73: Claire – After

Chapter 74: Claire – After

Chapter 75: Duncan – After

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1 (#u1b424c42-aaad-583a-a9e1-bd4410cbe6e6)

CLAIRE – BEFORE (#u1b424c42-aaad-583a-a9e1-bd4410cbe6e6)

There’s a dog protesting from one of the cages on the ward. Pain, the animal’s in pain. Its cries cut across my thoughts and I turn away from Duncan’s consulting room, past Sally on reception and through the doors to the back of the building.

Imogen, the animal care assistant, is already there, doing her rounds. Her body is bent as she checks each animal. She reads the clipboards pegged to every cage and tops up food and water.

‘Is it the Great Dane again?’ I ask.

She nods, gesturing to the biggest enclosure. It’s out of sight by the stockroom and I turn the corner. The dog is on its feet, swaying from side to side, one back leg visibly shorter than the other. It lifts its head, jowls wet with saliva, pressing its cheek against the bars. Large brown eyes roll as it recognises a human face and it howls again, a long two-toned cry, setting off another sequence of barks and whimpers in the room.

I unhook the door, dropping to my knees. The Great Dane hobbles cautiously towards me. It easily matches me for height in this position, pushing against my body. I take the animal’s head into my arms.

‘Hey, there, big fella, how’re you doing?’

I shift my feet, holding one hand to the side of the dog’s head, the animal panting. Its eyes are dilated, its tongue hanging out, tasting the very smell of me. The dog tugs away, distrusting even the comfort of my body, yet drawn to me. Its oversized legs are partially splayed, its tail tight and stiff. I run my hands along the underside of its stomach, pausing in the middle before slowly rising up and along the back, approaching one hip. The animal lets out a moan and throws its head like a horse.

‘It’s okay, sweetheart, I know.’

I press with care, eyes watching the dog closely, pressing just enough to determine the exact spot and no more. The dog moans again and I let my hand drop.

‘Imogen.’ I raise my voice. ‘Can you come and help me here a moment?’

‘Coming!’

I hear the clatter of a metal bowl being set on the floor and Imogen appears, slightly out of breath.

‘What is it?’

‘How long has she been like this?’

‘Since I came in this morning.’

I frown. My hand reaches up to turn a page on the clipboard.

‘Has she eaten at all?’ I nod to the full bowl of dried food pellets.

‘She had some of the wet food last night, but none of the dried.’

‘But she’s drinking?’

The water bowl is full too, I note.

‘Claire – I’m not sure …’ Imogen looks at me uncertainly. Then: ‘Yes – I filled it only a few moments ago.’

‘Okay. It’s happened again – she’s dislocated her hip …’

‘Claire!’ It’s Duncan, my husband, striding round the corner.

He stops in front of us, lifting one hand to his smooth round head. He towers over me as I crouch on the floor and glares at me with barely concealed annoyance.

‘Claire. Sally said you were looking for me.’

His voice is clipped and professional. He smiles at Imogen.

‘Would you give us a moment?’

She throws me an anxious glance.

‘Sure,’ she says. ‘Lovely to see you, Claire.’

Duncan’s arms are toned, his neck bare against his dark blue tunic. His name is embroidered on the front pocket: Duncan Henderson, Clinical Director. He waits until Imogen has gone, then turns on me.

‘What are you doing, Claire? I really don’t appreciate you coming onto the ward like this. It confuses the hell out of the staff and undermines my authority. We’ve talked about this before.’

He steps between me and the Great Dane, gently pushing the dog back into its crate.

‘Come on, now,’ he says to the dog. ‘I know, I’m sorry. But you’re next, I promise.’ He pats the dog.

I feel the heat rising up my neck. The Great Dane moves slowly around in the confined space, claws tangling in the blanket at its feet. Water spills from the bowl. I feel clumsy and embarrassed as Duncan slips the door catch back into position. He turns to me, but I speak before he does.

‘She’s got a dislocated hip and I noticed the femoral head on the x-ray—’

‘Have you been going through my notes?’ He’s openly angry now.

‘You left them on the kitchen table,’ I say. ‘It’s the second time this month, isn’t it? Dislocation. Manipulation isn’t going to work this time, there’s a—’

‘You need to go, Claire. And leave me to do my job. Why did you come here?’

‘I …’

I don’t know what to say. I came to say hello? He’s not going to believe that. I thought … I don’t know what I thought – that there was still a way for us to connect? When we were newly married, we always discussed difficult cases. As I look at his face now, I know he doesn’t even remember that, or doesn’t want to. And he certainly doesn’t want to hear what I have to say about the Great Dane. Well, screw you, Duncan, you can work it out for yourself, then.

‘Nothing. I was in town and I was dropping off the notes you left behind.’

I rummage in my bag and produce a folder. He takes it, our fingers not even touching.

But that’s a lie. The file is just an excuse. I know there’s no point in trying anymore.

I came for a look, to check out the staff. To work out if … which one of them, this time, it might be.

CHAPTER 2 (#u1b424c42-aaad-583a-a9e1-bd4410cbe6e6)

CLAIRE – BEFORE (#u1b424c42-aaad-583a-a9e1-bd4410cbe6e6)

I was never quite sure about this house. It’s not a house, it’s a barn. A great, vast tomb of a place, all gleaming sleek lines and huge panes of glass. Very beautiful, very impressive, but not a home. Not at first, not to me.

Duncan said I’d get used to it. All that space, the mod cons, the view – that amazing aspect over the valley. It’s Derbyshire at its best, lush and verdant with the reservoir glittering at the bottom of the fields. And the privacy. There’s not another house for at least a mile in each direction, who wouldn’t want that? And even I had to admit, I did appreciate the privacy.

But home to me is smaller. Shoes by the back door, coffee stains on the table, dog hairs on the sofa, knick-knacks, photographs and postcards cluttering the mantelpiece. A proper mantelpiece, not one of those engineered slabs of wood buried in the wall.

If he clears my stuff away, I discreetly put it back. And if Joe, our son, or Arthur, the dog, leave muddy footprints on the tiles, I cheer. That first scratch on the polished work surface in the kitchen was uniquely satisfying. Always striving for perfection is not much fun.

The front door glides shut with a soft clunk. Duncan has gone to work. I hear the smooth hum of his car and the measured crunch of wheels on gravel. I stretch out the fingers of my hand and roll my shoulders. Then I gather my long hair at the back of my head and twist it into a loose bun. Strands of brown hair fall on either side of my face; I never was much good at grooming.

The wind gusts across the walls of the house and a sweep of rain splatters against the full-height window in the sitting room. I see my own shape reflected back; it makes me look taller, larger than I am, at least that’s what I tell myself. Strong. The sky is green, not grey, coloured by the triple-layered tinted glass so that even the view is tainted by Duncan’s choice of architecture.

Everything about this place was his choice, not mine.

I turn back to the sink. The deep-set window behind it was the only thing left unsullied by the builders. At my insistence. One last remnant of the building that was before, the old cottage that stood beside the barn. I would have kept it whole, perhaps linked by a glass atrium, but Duncan wanted it gone, to focus on the barn itself, stripped and open to the roof. There’s not much sense that this was all once a busy working farm.

As I plunge the mug into the hot water, I see my son, Joe, crossing the lawn from the top field. His head is bent against the weather, his dark hair damp and curling against his neck.

Moments later, the utility room door flies open and dead leaves bluster across the floor. Arthur, our black Labrador, scampers inside. His jaws are slack, drooling with saliva, and he shakes the rain from his coat so that water sprays on to the cupboard doors. He heads for his metal drinking bowl and I hear the sound of his tongue pushing it across the floor.

Joe hops on one foot and then the other, slinging each boot into the corner by the ironing board.

‘For heaven’s sake, Joe, take some care!’

He ignores me. He doesn’t even look up as his awkward frame passes into the kitchen.

‘Where have you been?’

It’s a stupid question, I know the answer. It’s almost eight o’clock in the morning and he’s been out all night. Not clubbing or drinking like most teenagers – I should be so lucky – but out there, in the fields.

Joe doesn’t reply and I see that ‘thing’ he always takes with him, the metal detector. He’s left it against the wall, looping the headphones and cable over the handle. He crosses the kitchen to find the biscuit tin, fishing out a handful of digest-ives. He shoves one in his mouth and the rest stick out from between his fingers like the roof of the Sydney Opera House.

‘Joe!’

I raise my voice, trying to break into his thoughts, but he simply gestures to his full mouth with his biscuit knuckle-duster and leaves the room. I swear I love my son very much, but his lack of eye contact cuts right through me sometimes, even now after all these years.

Today, he seems more than usually distracted.

He takes the stairs two at a time. A door bangs and the music starts. Thump, thump. Rude and raucous and irreverent. Very satisfying. The volume blasts up a notch, a heavy tuneless beat that reverberates through the ceiling. There’s the surge of hot water from the shower in the bathroom. The sound carries across the open roof spaces in the barn. You can hear everything, despite the distance. I let it wash over me. It’s the silence of the house that gets to me, when he isn’t here. Like a cathedral with no worshippers, a grand theatrical production that no one comes to watch. But when he is here, the noise of him annoys me, too. Eventually. There’s no pleasing me. My mouth twists into a smile.

At least he’s looking after himself. Not like before.

I dry my hands, leaving the towel dumped untidily on the kitchen island. I pour hot water from the kettle into a new mug. My fingers reach around to comfort myself and I breathe in the warm steam. The familiar smell of coffee tickles my throat. Familiar is good: a hot drink, a slab of bread thick with butter. It grounds me.

At least this time my son has come home.

‘There was this man ten years ago who discovered a hoard in Somerset.’

I’m prepping tea and Joe is sat at the kitchen island with a long glass of milk in his hand. He fidgets on his seat, as if he can’t stop himself from moving.

‘It was in a field next to an old Roman road. He’d found a couple of coins and ended up discovering a clay pot of some kind, sunk into the ground. It was crammed full of coins – can you imagine that?’

He doesn’t wait for me to answer.

‘And so heavy you couldn’t possibly lift the whole thing out. The sides of the pot were broken and he had to leave it in place, carefully removing the coins under cover of night. He did that so that no one else knew what he’d found.’

I have an image in my head of an old man in his cardigan pulling out green coins with his bare fingers by the light of the moon. I have to smile.

‘Layer by layer, coin by coin, over several nights, until the whole thing was extracted. He didn’t report the find till after that. There were more than fifty thousand coins in total!’

Joe loves telling me these stories, when he finds his voice. It’s his dream, finding a hoard. When Duncan’s not around he talks about it endlessly, the different coin types, how to date them, how to clean them, the different patterns on each side.

‘The rules are complicated,’ he says. ‘And the coroner has to be told.’

Joe’s told me this so many times. I’d always thought coroners only dealt with the dead, but they deal with treasure too, apparently.

‘They have to estimate the level of precious metal content – that’s important when it comes to what happens next and how much the find is worth … Mum, are you listening?’

‘Course I am, Joe. You were telling me about the coroner.’

‘No, I was telling you about metal content.’

He flashes a look of frustration at me. Then he’s off again, detailing different measurements, his hands animated, his body leaning over the kitchen island, gulping down his milk in between long, rambling fact-filled sentences.

It’s a boy thing, I tell myself, all that data and statistics, the kind of information overload that makes me want to walk away but sets Joe on fire. All I can think is, at least he’s doing something constructive, active, and he’s communicating with me. I feel the guilt of my disinterest wash over me. It’s nice to see him on fire.

‘Come on, Joe, that’s enough for now, tea’s ready. If you drink too much of that milk you won’t be hungry. Help me take this through to the table.’

I shouldn’t begrudge him the milk. As a teenager, he guzzles the stuff. Listen to me, I sound so much like the mother that I am. Joe goes to the fridge for more milk and I text Duncan upstairs to say that tea is ready.

We eat in silence. Duncan pushes the pasta into neat piles before scooping it into his mouth and Joe shovels it like a farmhand clearing out the stables. I glance between the two of them, the one with too little hair, the other with too much, and then Duncan’s mobile beeps.

His fingers tap twice and inch towards the phone, then he pulls back.

It beeps again. He looks at me. I refuse to look at him and Joe keeps on eating. After a few minutes, I push my plate away, all pretence at hunger gone.

Then the stupid thing beeps again.

‘Can’t you switch it off?’ I say.

My voice is quiet but sharp and the pulse at my neck is racing. Duncan’s eyes meet mine then slide away. He carries on eating as if I haven’t spoken.

Lo and behold, the phone beeps again. I feel my cheeks suck in and taste the blood on my tongue. I reach for his phone and he grabs it just in time.

‘No phones at the table, we said. Remember?’ I let my voice twist into a sneer.

‘I’m on call,’ he says.

‘Like hell.’

Joe stops in mid-forkful.

‘It’s only work, Claire. You know that.’ Duncan’s tone is smooth and appeasing.

I hate him when he’s like this. As if I’m a child, playing up, or a fool, easily deluded.

‘No, it’s not,’ I say. ‘We both know it’s not.’

‘That’s nonsense, Claire, you’re being paranoid.’

He arranges another pile of pasta.

‘Oh, really?’

Joe is watching us both, eyes wide and unblinking. It reminds me of when he was little, still trying to make sense of the world. Like when we shared a bedtime story, his gaze glued to me as I read, not the book. He’d follow the cadence of each word on my face. I drop my eyes, curling my fingers and breathing long and slow, trying hard to keep it in. But my eyes are drawn back to the phone and then Duncan. He’s actually smiling, like it’s a game.

‘How can you sit there and pretend?’ I say. ‘Day in, day out. How can you do this?’

He doesn’t answer. His fingers tap again and he stands. He picks up his plate and turns round, his back stiff and unyielding. He moves into the kitchen. I hear the click of the automatic bin and the clunk of the dishwasher. A few minutes later there’s the swoosh of the front door. He’s gone. And Joe goes back to eating.

I think of the papers hidden in the folds of the magazine by my bed. The appointment I’ve made for tomorrow. Duncan thinks that nothing’s changed. That I’ll stay, like I always have. But our son is eighteen now; he left school months ago. He’s all grown up, a legally independent, responsible adult.

And I’m the one in control here, not Duncan.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_1656b7d1-ac1f-52ee-9525-e4cc4040d9bd)

DUNCAN – SIX WEEKS AFTER (#ulink_1656b7d1-ac1f-52ee-9525-e4cc4040d9bd)

Duncan’s gloved hands were stained with blood. The dog’s skin was peeled back, revealing the bloodied bone and yellow subcutaneous fat. The radio played softly in the background and the monitors beeped with a reassuring regularity as he dabbed at the opening with a swab.

There were three of them: Duncan and Paula, the newest vet at the practice, and Frances, the senior nurse. Their legs and hips were pressed against the operating table and the light blazed a harsh white over their heads, picking up a glint of red hair from beneath Paula’s surgical cap.

‘Okay,’ said Duncan. ‘Let’s get this little chap put together again.’

He tugged gently on the flaps of skin, pulling them towards each other. It was a struggle; the dog was barely a year old and the metal pins holding the leg bones left little space for the original skin to meet. Duncan shifted the skin a little higher.

‘Frances – can you hold it there?’

She took the clamps into her hands.

‘Left a bit. Hold it … wait …’

Duncan pursed his lips and pulled again, reaching in with a suture needle, feeding the thread between his gloved fingers to make the first stitch.

‘Excellent,’ he said. ‘And another. Paula, can you clean around here?’

They worked together in silence. Ten minutes later, the opening had been closed. Frances gave a relieved smile and Duncan took a step back.

‘That’s it. Thank you, both. I’m glad to see that one done.’

‘She’s looking good,’ Frances replied. ‘You should go and ring the owner. You’ve earned that. We’ll finish off and resuscitate. I’ll see this one to the ward.’

Frances smiled again. She was older than Duncan, her darker skin and years of experience warming her features, the lines around her eyes creasing above her mask.

Duncan pulled the gloves from his hands, dropping them into the refuse bucket. He tugged the mask from his face and left the room, pushing the door with his shoulder and reaching up to rub his neck. Three hours on one dog – the smaller animals were often the most difficult. But it had been a success. He headed for his consulting room to make the call.

‘Duncan!’

It was Sally on reception. Her usually straight blonde hair was falling unkempt about her shoulders. A collection of dirty coffee mugs stood by the phone and the printer was spewing out blank sheets of paper. As ever, the room was busy with people and animals. Duncan nodded briskly at the man who lifted one hand in greeting.

‘Yes?’ Duncan responded to Sally.

‘Call for you – urgent, they said. I’ll put it through.’

He mouthed a question and Sally shrugged her shoulders. Her lips said police. He glared at her and she jabbed one finger towards his consulting room.

‘Okay,’ he said, biting down his emotions.

‘Duncan Henderson, here.’

He sank into his chair and swung round to face the window.

‘Duncan, it’s Martin. Very sorry to disturb you at work. I’m afraid I have to ask you to come back to your house.’

One phone call, that’s all it took to hijack all those appointments. Duncan turned his car up the drive to his house. The constant slash of rain against the windscreen had left him with a painful furrow of concentration on his forehead and a thick spray of black mud on the paintwork of his car. The vehicle slowed on the deep gravel, cruising between the pink cherry trees that lined the drive. Spring had been interrupted by a blast of cold, stormy weather, and wet leaves and translucent blossom clung like damp butterflies to the big sheet window. The barn glowed a peachy flushed red.

Duncan felt his heart contract, his jaw tighten. There were cars and vans slewed every which way they could, blocking his usual turning circle. Beyond the perimeter fencing, where the fields tipped towards the silver bowl of the reservoir, already a double line of blue-and-white plastic tape rippled down the slope.

He squeezed his car into a gap, in the corner where Claire used to park. He got out. The grumbling blast of a generator assailed his ears. A pair of uniformed officers stood by the top gate, stiff and upright like tin soldiers. By the garage, a tent had been pitched up, and in the distance, at the bottom, were more tents, slick with wet. Grey sheets of rain blustered across the valley and figures in white hooded overalls ran across the scrub. The whole scene had the surreal air of an alien landing site.

Duncan approached his front door.

‘Excuse me, sir. Can I see some ID?’ An officer appeared at his shoulder.

Duncan swung round to face him.

‘I live here,’ he snapped.

‘Even so, if you don’t mind.’

Duncan scowled and fished out his driving licence. There was an awkward pause as the officer scanned the photograph.

‘Mr Henderson, thank you. The boss said to have a word with you as soon as you arrived.’ The man gestured towards the first tent. ‘If you don’t mind.’

The boss. DCI Martin White. They’d known each other since their first day at school.

‘This way, please, sir.’

The tent opening thrashed in the wind. Inside a huddle of officers stood around a table with several computers, and their papers scattered upwards as the flap fell back into place.

‘Duncan?’

A man looked up, his hands holding down the papers. He wore a green waxed jacket, his grey suit loosely buttoned underneath. His hair was cut close to his head, black peppered with white, and a broad platinum wedding ring glinted from the back of his hand.

‘Martin.’

Duncan wiped the rain from his forehead. The police team wasn’t huge for the area, it was inevitable that Martin would be in charge. Duncan had a brief image of Martin standing by his side in the registry office at Claire and Duncan’s wedding, leaning forwards in his shoes, discreetly scanning the room like some kind of security officer.

‘Thank you for coming back,’ said Martin. Their eyes met. ‘I expect this is a shock.’

Duncan didn’t reply and Martin dipped his head in acknowledgement.

‘I’m sorry to be here in these circumstances. And I apologise for the disruption. But I’m sure you understand why this is necessary.’

Duncan’s eyes were drawn to the table. There was a shallow crate covered in a cloth.

He felt his body sway, unaccountably off balance. He clenched his hands and pushed them down his side, forcing himself to stay upright.

‘Cup of tea, sir?’ A younger man stepped forwards, offering Duncan a mug.

‘Do you think I want a fucking cup of tea?’ Duncan turned on the man, eyes flaring.

A blue light flickered from one of the computer screens and the wind sucked at the canvas over their heads. Silence had fallen on the tent.

‘I’m sorry. I …’ Duncan pushed his hand across his head, rubbing the bare skin, then smoothing down to the closely cropped hair at the back of his neck. His jaw moved and his eyes closed momentarily.

‘It’s alright, Duncan.’ Martin followed his friend’s gaze. He gestured to a chair. ‘Everyone here understands. Why don’t we sit down?’

Duncan shook his head. He stood still, his arms held stiffly by his side.

‘No,’ he said. ‘I don’t want …’ Duncan’s breath heaved in and out and his eyes were pulled once again to that crate.

Martin took a step closer.

‘Duncan, look at me. It’s okay. Look at me!’

Duncan lifted his eyes to Martin. It seemed to him there were just the two of them then, in that tent, all sense of the outside, the weather, the people, the cars on his drive, banished to the edges of his mind.

Then he took control of himself, responding to Martin’s unspoken signal.

‘What exactly have you found?’ He pushed the words out between his lips.

‘Human remains. A body has been found by the shore at the bottom of your land.’

Martin paused, as if unwilling to broach what came next.

‘What kind of body?’ Duncan said.

There was another pause.

‘Come on, man, you can’t not tell me!’

‘We’re not sure yet. I’m sorry, Duncan, that’s all I can tell you right now.’

Duncan made himself move, reaching out one hand to clutch the table, forcing himself to stay focused.

‘I don’t understand … I …’ His body swayed.

‘Duncan, are you alright?’

Martin took a step forwards.

‘Duncan—’

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_f62e6689-9f49-5bae-8a18-2c60f186a038)

CLAIRE – BEFORE (#ulink_f62e6689-9f49-5bae-8a18-2c60f186a038)

‘Hey, Becky. How are you this morning?’

I can hear a voice in the background, the clunk of crockery and a tray being set down on a table.

‘Are you up to a visitor around twelve?’ I ask.

‘Yes, please,’ says Becky.

She sounds happy. One of the things I’ve always loved about Becky is her cheeriness. Upbeat and optimistic, despite her circumstances.

‘Great. I’m in town anyway this morning to do some jobs. I’ll bring us some lunch, shall I? Fish from the chippie sound okay?’

‘Sounds perfect,’ she says. ‘It’ll just be me. See you then.’

The phone clicks and she’s gone.

Town is busy. It’s market day and the car park on the small square has been taken over by stalls and vans. Every street is filled with parked cars and the cobbles judder under my wheels then disappear as I turn into the customer car park of the veterinary surgery. I ease the car into a spot furthest away from the front door. One of the advantages of being the boss’s wife is I get to park for free whenever I need to. Through the glass doors I can see the reception desk, the familiar head of Sally bent over the screen. I walk out of the car park, dodging the bus shelter to head towards the main precinct and the estate agents behind the town hall.

‘Hi,’ I say to the young man leaning back on his chair behind the desk nearest to the door. ‘I have an appointment. Claire Henderson.’

My head swings over my shoulder, scanning the street outside. I will the man to speed up and he senses my agitation.

‘Sure. Hold on a minute,’ he says.

He tips forwards and pushes away, standing up to disappear into a conference room. When he comes back, I think how he doesn’t look much older than my Joe, a narrow blue tie swinging against his crisp white shirt. Except these days you’d never catch Joe in a white shirt, let alone a tie.

‘This way,’ he says.

I move too fast into the conference room.

‘Hello, there. Do sit down.’

This agent is older than the lad by the front door. Hungry-looking, like one of those midsized birds of prey hovering over a small animal by the roadside. He’s assessing me.

‘Mrs Henderson, how are you?’ He doesn’t stand up but reaches out a cold hand.

It’s one of those questions you’re not supposed to answer. I contemplate actually telling him. Do you really wantto know? says the voice in my head.

‘I think I’ve found the perfect place for you,’ he says. ‘Not too far, like you asked. Though perhaps a little closer than you wanted, but there’s not a lot out there on the market at the moment. It’s near the reservoir with a bit of character and a fantastic view.’

He pulls out a one-page leaflet with a small flourish, pushing it under my nose. My eyes scan the paper and I have a brief impression of a rambling old cottage with a defunct hanging basket blocking the back door and a roof that sags in the middle. Character – that’s one way of putting it. Agent-speak for a house that’s small and run-down and probably expensive to heat. He taps on the rent.

‘It’s four hundred pounds a month.’

That is cheap for round here. The location is doable. It’s on the other side of the dam, so there would be a wall of concrete between me and Duncan. How appropriate, I think. I glance up at the agent’s face.

‘Can I view it?’

‘Of course you can.’ He smiles. ‘Let me check the diary.’

He snaps back to his PC, scrolling down the screen.

‘How about on Thursday, eleven am? My colleague, John Hardcastle, will show you around.’

I nod. He starts to type.

‘Can you remind me of your current address, Mrs Henderson?’

‘Brereton Barn, Hob Lane.’

‘Ah! Yes, of course, lovely spot.’

He doesn’t ask why I’m looking for a place to rent. Or why I don’t want to buy. And he doesn’t ask about my financial circumstances. He knows of my husband, the town supervet, with his shiny new practice and growing reputation, living in one of the poshest houses in the district. Why else would his wife be searching for a new home? Instead, the agent looks me briefly up and down, as if speculating if Duncan knows yet. Everyone knows everything about your business in this town. It won’t be long before the gossip spreads.

Which means, now I’ve started this, I’m already running out of time.

‘Ooh, that smells amazing!’

Becky pokes her face into the greasy papers and takes a good long whiff. Her short hair is fluffed up and she gives me one of her big open smiles, freckles creasing on her cheeks. I’ve always envied her that smile – it lights up the room. Duncan has the same smile, when he chooses to use it, it’s one of the things I loved about him when we first met, but that’s where their sibling likeness stops.

‘Sinful, but who cares!’ she says. She grins again and places the package on the table.

‘Where’s Alex?’ I ask, referring to her son.

Becky swings back to the cupboard to pluck out a cheap carton of salt and some vinegar.

‘He’s at the day care centre. Dropped him off earlier. We’ve got a couple of hours.’ She turns back with a plate in each hand and slides onto a chair. ‘Grab us some cutlery, will you?’

I rummage in the drawer behind me and Becky tips the food onto our plates. There’s a moment of silence as we both dive in with the same hungry enthusiasm as Arthur after a long walk.

‘Mmm, this is good. So …’ Becky catches my eye. ‘How was your appointment?’

Appointment? I feel a prickle of alarm; I hadn’t told her I had an appointment. I haven’t told her anything yet. How can I? She’s Duncan’s sister for all she’s my best friend and I don’t know where to begin to explain that I’m about to leave her brother. Besides, I need to finalise things and tell Joe before I tell anyone else. Let alone Duncan. I owe him that at least.

‘It was okay.’ I force myself to relax. Becky’s just interpreting the ‘jobs’ I mentioned on the phone. ‘Boring stuff with the bank.’ I scatter salt on my chips. ‘I had to sign accounts and stuff, what with technically being a director of the business.’

How easily the lie slips from my tongue. Not that my story means very much. Yes, I’m listed as a director of the surgery, but Duncan’s always been fiercely protective of his business. He doesn’t let me see anything.

‘You should make him let you work there. Alongside him as a partner.’

‘Oh, God, no. I mean, I like the medical stuff, and the research especially, but the business side of things? We’d only argue. We have quite different ideas about how to manage things. No, I could never work alongside him. Besides, it’s been such a long time since I was in the profession …’

‘Come on, Claire. Joe’s eighteen now. You’d pick it up again. I know you, you’ve kept up to date with all the science and I bet you’ve been hankering to go back to work for years. And you’re darn clever, every bit as much as Duncan. I know you’ve had Joe to deal with, but he’s settling down a bit, isn’t he? Not like before.’

Not like before. All those years of Joe screaming at the teachers. Joe digging his heels in and refusing to go to school. Joe disappearing for days on end and driving me frantic. I bite my lip. The last time Joe went missing for over a week, it was just before his A-level exam results. Perfect timing. But who am I to complain about my son? Becky has far more to deal with than I. She puts me to shame. My son is hale and hearty. Her son, Alex, is confined to a wheelchair, profoundly physically disabled.

‘It’s true,’ I say. ‘I’d like to go back to work. I have thought about it, but I’m not sure.’

It’s half a truth, isn’t it? I have every intention of going back to work. I’m going to have to, we’ll need the money, Joe and I. But not with Duncan, and probably not even here in Belston. Derby, perhaps – or further afield, if I have to go that far to find the right thing.

Whether or not Joe will stomach it. After.

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_276d6d6d-fe47-58e2-9dcd-e94cdb8421e2)

CLAIRE – AFTER (#ulink_276d6d6d-fe47-58e2-9dcd-e94cdb8421e2)

The horse moves with a fast, rhythmic pace, its broad back swaying beneath its rider’s legs. I watch them pass the giant shrubs of rhododendron that block out the light. Their buds are almost pink and the leaves are almost black, gleaming in the cold, steady rain.

They ride on, beyond the gardens. Into the woods. The mist hangs low over the canopy of trees, lingering with the reluctance of the newly deceased floating over a still warm bed.

The reservoir is visible now. Not far. I hear the water lapping and the ducks calling to each other in the reeds. A pheasant hurtles from the banks, a flash of red, shrieking, guttering, the sound bouncing along the shore like stones skipping across the water.

The young man’s head scrapes across the ground, the weight of it dragging on his neck. I can almost feel the pain that must be spreading across his body, his shoulder blades and back. Each thump and drag of his head erupting like fireworks behind his eyes. I feel it as he feels it, as the rider slows the horse to a walk. The lad tries to lift his head, only for it to fall. His body lurches into movement as the horse moves on, pulling upon the rope.

He is like a stick floating on a stream, stones and earth, the lumps in the ground forcing his skull up and down, buffeting him this way and that. Black mud is smeared on his face and his wet clothes cling to his body, sucked in against his frame so that the bones are clearly visible. I see him try to lift one arm – his arms are free, but not his legs. They are tied. The rope red around his bare ankles. The rider shifts his grip, nudging the horse with the heels of his boots again, urging her to move faster along the path beside the reservoir.

The view opens up. The full expanse of water is revealed. A glint of metal pierces the surface not far from the shore. The slender shape is half tipped, draped with soft black weed, as if poised between two realms. It hasn’t appeared for a hundred years, not since the summer of 1918. The last year of the Great War. One cross in a field of crosses, marking the growing dead. That’s what they’d said in the village then, as the women grieved for their men.

The cross is taller than before. A spindle, sharp enough to prick a finger.

My gaze returns to the boy. I see the debris brushing against his cheek, how the clagging scent of the forest makes him want to retch. He tries to cough but the angle is all wrong. His chest must be burning from the effort to breathe, his tongue swollen, his airways blocked, his flesh bloated like rehydrated seaweed. They’re right on the shore, riding over stony mud, and it drags against his flesh. The speed at which they’re moving and the grogginess of his brain means that all he can do is flap his arms uselessly like a drunken swimmer until they fall back above his head and the ground beats and pounds his skull and he’s near faint with the pain of it.

I am consumed by nausea. I feel it as he feels it, everything blackness and confusion. His brain – my brain – stuck inside my skull like the tiny building in a glass globe. Snowflakes, I see thousands of snowflakes fluttering into life, my head fixed but everything else loose and drifting.

The horse’s hooves sink into the mud. Water swirls about the rider’s boots and the boy floats. The rider tugs on the rope and his hair blows across his face and the metal cross shines, dazzling his eyes as he waits for the geese to pass, for the mist to draw breath. For the spire to sink from sight and the sun to rise unseen and the breeze and the birds to settle.

There’s a voice in my head. ‘It shouldn’t have been like this,’ it says. ‘If only the boy had accepted his fate and stayed upon the island. They wouldn’t have had to do this.’

The rain has turned to snow, the snow has turned to hail and stones of ice pitch down against the water. The rider spurs his horse again and again, and she plunges forwards into the lake, deeper. As their bodies begin to disappear, the rider’s face turns back towards the shore. His lips move and I hear his voice, even though he does not speak.

‘Hasn’t it always been like this, Claire? Especially with the young ones.’

Our eyes meet.

‘They just don’t want to die.’

I let out a soft moan and my head rolls to one side. The mattress heaves beneath my body and beads of damp trickle down my skin. The air in the room sweeps cool across my face and I slowly open my eyes, blinking once.

Then I remember.

Joe, my son, has gone.

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_54170cc3-4cae-51ed-91da-19714b298291)

CLAIRE – BEFORE (#ulink_54170cc3-4cae-51ed-91da-19714b298291)

I’ve met the agent, Hardcastle, at a gate marked Private. He’s standing by his car, waiting for me. A man in his later years, short and round, he wears a loud pin-striped suit and he looks like he doesn’t quite belong, here, in rural Derbyshire.

I press the button to lower the window. He leans down to speak to me.

‘Mrs Henderson. Delighted to meet you.’ His voice has the strangled tones of an independent education. ‘Oh, you don’t need to worry about that,’ he adds.

He dismisses the weatherworn sign with one hand. Rust obscures the top half of each letter and it swings in the wind, back and forth, with the inevitable regularity of a metronome.

I follow Hardcastle’s Mercedes in my functional estate. We could have afforded better, but I like my car; I don’t have to worry about every scratch, unlike Duncan, obsessing about his smart Lexus SUV. He has the more reliable vehicle, since he has to go in and out in all weathers to get to work. Hardcastle and I drive one behind the other, bumping along the road parallel to the edge of the reservoir until we turn up into the old village.

I know the village well. I know the whole valley. I’ve lived in the area for so many years. On my right is the dilapidated farmhouse skirted by a straggle of barns. On my left, a sequence of run-down cottages. Some of them face each other like partners in a dance, each house wearing its abandonment with an air of genteel humility – lichen-dusted walls, plants peeping from the gutters, window frames faded and stripped by the sun. The windows all have the same delicate white leaded inserts and the doors, the same peeling blue paint. Even the brickwork is all a matching shade of Georgian herringbone red, warm and welcoming but for its neglect. Gorgeous in the crisp morning sunlight.

It should have lifted my spirits, all this. The evident decay of the village simply adds to its charm. And yet there is no sign of life. Never has been. No washing on the line, no pot plants in the windows. Not even a bowl of water for a cat or a dog. Most houses in the country at least have a cat to keep down the rodents.

I see a ramshackle pair of iron gates with a drive leading into the shadows. There are no cars, not one by a single house, except for us, of course. I’m not sure I like it. The whole village is resolutely derelict. I’ve avoided it before. I hadn’t realised the property would be so close to here. It’s on the far side of the reservoir away from the Barn.

We pass the last house and turn off again, climbing the hill. Hardcastle takes a left, off the lane onto a dead-end track where the tarmac has melted in the heat of last year’s summer. I follow and the grass verge is so overgrown you can’t see past each bend. The trees and hedges grow so tall and dense that the fields above are hidden. Daylight has morphed into dark shadows, bathing the track with the shifting patterns of moving branches, and I jam on the brakes as a squirrel bounds across the lane right in front of me. I have one of those unsettling moments of déjà vu, like I’ve done this before. But I don’t think I’ve been up this way, why would I? That’s good then, I think.

Then we’re there, at last. The cottage.

I feel my heart skip a beat. It’s a wreck. I expected it to be, but I still love it.

To be fair, they did warn me of the state of it: In need of some development. Landlord happy for tenant to make the place their own. Translate that as damp and cold from years of neglect and in need of total renovation. If not tearing down and starting all over again. Not that that’s an option.

It must have been standing empty for several years.

The building sits sideways from the track, with red bricks and white painted windows like all the other houses in the valley. It wears its slouch like a tired old man. I cast my eyes down the slope. You can see the reservoir in the distance, exactly like they’d said. My heart gives another leap. Not too close, but close enough.

I’d promised myself it had to be something located near the Barn, ish, painful though that is. I don’t want Joe to have any excuse to refuse to come with me. He won’t give up his metal detecting and I won’t take him too far from his father, despite all the conflict. I want to reassure him about that. They still need to see each other and I won’t have the money for expensive train and bus fares. Besides, there are so many secluded corners in this valley, old farm buildings and shepherd huts slowly degrading beneath the weight of their own walls, I think it might just work hiding from Duncan in plain sight. I have faith in Joe, he won’t let on if I ask him not to. If I need to. I suck my bottom lip between my teeth.

I park my car beside the estate agent’s and get out. As I follow him up the short, overgrown path, he reminds me of the rent. I lift my head and he smiles at me with the wide-eyed confidence of a salesman who knows he’s already got the deal. We come to a stop and he looks away, restless, like now we’re here, he’s already thinking of the next appointment.

‘Why are they renting and not selling?’ I ask.

Not that I can afford to buy until the divorce comes through. This is only temporary, I tell myself.

‘It’s part of an old estate. The family aren’t prepared to sell. They don’t want to break up the estate.’

I nod. I know about the family. Everybody does. There are a few stories about them, none of them particularly salutary, mostly around unreasonable rules and wilful neglect.

The agent gestures to the view beyond the cottage, over the fields and down the hill. He launches into his spiel.

‘Lovely, isn’t it? The whole valley is subject to a ninety-year-long restrictive covenant, so nothing’s been built, not even a shed, since the Second World War. People pay over a million for those few houses further up the hills …’

His voice trails away. He knows I must be aware of this. He’ll have seen my name and address on the contact form. Wife of, mother of, Mrs Henderson – is that all I am to other people? Even in this day and age, defined by my relationship to men. That’s what you get if you choose to be a full-time mother. Certainly, in this part of the county. Though choose isn’t quite how I’d put it.

Hardcastle steps ahead of me and unlocks the back door, shoving it hard to get it to open. It grinds in a painful way due to the loose stones caught under the bottom of the door.

‘You’ll be hard-pressed to find anything prettier in all of Derbyshire.’

I look up – he’s right, the cottage is very pretty, in a down-at-heel, scruffy kind of way. Shabby chic, that’s how I imagine it could be, picturing it with whimsical fairy lights and vintage candles. But the view down to the reservoir still pulls my eyes. A thin trail of mist slithers out low across the surface and a large bird breaks through. Another and another, a line of geese rising up. Beating wings, open beaks, their gulping cries breaking the peace of the countryside. Their wings pull with a steady rhythm as the mist parts and coils out of place, and the yellow light from a weak sun dances briefly across the water.

The agent smooths his hands down his tie – silk, so much classier than the young man who greeted me at the office. That super-confident smile of his is making my stomach curl.

‘It’s a project, like I said.’ He croons like a jazz singer. ‘It means you’ve got the freedom to decorate exactly as you please. The view is particularly striking from the master bedroom.’

Master bedroom. As if. Judging from the floor plan on the details there’s barely enough space for one double bed and a small cabinet. I contemplate the flaking wooden windows. There’s a second bedroom under the eaves. I might have to take that one, given how tall Joe is. A ‘doer-upper’, cloistered in a long-forgotten valley, the lush slopes the select preserve of one family, a couple of farmers and a handful of rich, obsolete businessmen.

I squeeze past the buddleia bush leaning out across the doorway and duck underneath a hanging basket that trails dead leaves over my head. I eye the drunken shape of the roof, its missing tiles and the grime-encrusted, cracked panes of glass in the door. As I step inside, I see peeling wallpaper and a mustard-yellow 1950s kitchen. This place, I realise, hasn’t been touched for decades. I feel my excitement bubble.

I move into the room and then I spot the ancient red enamelled range. It’s been pushed into an old inglenook fireplace with a blackened beam above, pitted and scorched with age. I run my fingers over the grooves in the wood, peering more closely. There are markings that seem familiar, circles within circles and letters too, a W and AM, carved with a crisp precision that have nothing to do with the natural cracks from the heat. I feel myself falling even deeper in love.

‘What are these?’ I say, fingering the marks.

I know the answer, but it’s something to say. The agent leans forwards.

‘Oh, those are witches’ marks, carvings from long ago, probably from when the house was first built. People did that stuff then to ward off evil spirits. It’s quite common in this part of the county. So you’ll be quite safe here.’

He grins in a rather wolfish way for an older man. Creep, I think. Then he turns towards the back door, pulling out his mobile phone.

‘I’ll let you look around on your own.’

He’s already lost interest, swiping at the screen.

I scan the ceiling. The brochure hadn’t mentioned that the roof leaked or that there was no central heating. I can see pipes running from the side of the range to the sink, then along the wall again and up into the corner through the ceiling. I’m guessing the fire heats the hot water. I daydream of waking early in the morning, heading down the stairs in the freezing cold to stoke the ashes from the night before, piling on the logs to relight the fire in the range and generate some heat. I could put an armchair right in front of it, with that old rag rug Duncan thought I’d thrown away. It would be perfect there under my feet. Flagstones, I see proper giant slabs of flagstone. I’ve always loved the idea of having those.

I wonder if I might even be able to buy the place if and when the family decide to let it go and my divorce comes through.

I feel my anticipation grow. A new routine to take over from the old routines of my life as it was before. I’ve been with Duncan for so long, ever since we were students together at the veterinary school in Nottingham. It’s hard to conceive of a life on my own.

Though, not quite on my own.

Joe has to come with me. I can’t go without Joe.

And Arthur, of course.

It’ll be Duncan left on his own.

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_02ebe3ab-f2e1-5e83-87c0-f70e39603b69)

CLAIRE – AFTER (#ulink_02ebe3ab-f2e1-5e83-87c0-f70e39603b69)

I wake. The bedroom is deathly quiet. The kind of silence that plucks the air from your lungs, eyes wide open listening for a creak in the walls, the flutter of birds in the trees, the switch of illicit shoes climbing the stairs.

It’s dark, the air cold upon my skin. I lie on the bed frozen to the mattress, legs bent, one arm under my head, eyelashes brushing against the pillow. I listen, hardly realising that I’m holding my breath until I let it go. My ribs move and I force myself to wriggle my fingers and pull one leg free from under the covers.

I have woken too early, too tense, the nightmare still filling my head. Fear pumps through my veins like a drug. It’s as if the bed, the whole room will implode, swallowing me up, dragging me down into a narrow chimney of thick stone and earth, falling, falling, scrabbling for roots and clumps of soil but unable to grab hold, water gushing through the gaps. I am Alice in her Wonderland, too big for the space, too small to fight back, too disbelieving of my fate, as I’m sucked down into a vortex of my own making.

I gasp and sit up, pulling myself out but into yet another new nightmare.

Joe?

I’m panting, dragging great lungfuls of air into my chest. I reach for the bedside lamp, pick up the clock and cast my eyes around the room. I see the spill of daylight growing through the gap in the curtains. For a moment it all seems strange, an alien place I’ve never seen before. The clock has a new face, the curtains a different pattern. Even the fragile dawn is a strange colour, sharper, cleaner, more luminescent than before.

I exhale and place the clock back on its table. I let the brightness bring me slowly back to life. That’s when the memory taunts me. The memory of my son.

I remember the sweaty, musky scent of him that clings to his unwashed clothes, the way his hair falls in lush waves across his cheeks. I hear his music, the thudding beat asserting his presence in the Barn. I smell the cold air on his coat, the dead leaves under his feet, the ice upon his skin. And something else – a damp, earthy, rotting kind of smell, like mushrooms spawning in the dirt.

I am awake. I must let it go, whatever it is that still pulls me to that dream. I will myself not to think of Joe like that. Instead, I think of the scent of him when he was newborn. That sweet Joe smell, my Joe – no one else’s Joe – nestled in the crook of my arm. His fingernails are soft and peeling at their tips, his knees folded to his chest. His skin is pink and white and blue, the strands of black hair on his skull slick with the soft grease of birthing. That smell.

I squeeze my eyes shut and push the memories away. Are they memories or dreams? I’m not sure. I have a fierce headache that won’t go away. They told me I will have to get used to it, that it’s to be expected after what’s happened. But as I lie here, I can’t even remember who said that or where it was. Only that he’s gone. My Joe.

He didn’t come with me.

I open my eyes, listening for his footsteps just in case.

I betrayed him. I left him behind. It overwhelms me, how I could do that. I can’t let myself think about it, my head hurts trying.

But now I hear something. There are footsteps, after all. I’m sure it must be him. I’ve been texting him all this time, making sure he knows where to go. At last, he’s come home! To our new home. The cottage. I hear a steady, cautious creak upon the stairs. My bedroom door swings open and a shadow reaches out across the floor.

It’s Arthur. The dog. His black head is up, sniffing the air. He pauses as if to check that it’s okay to come in.

He moves again, his three good legs bearing the bulk of his weight as he limps uncertainly towards my bed.

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_807a62a2-19ff-55fa-869c-0f8479033c56)

DUNCAN – AFTER (#ulink_807a62a2-19ff-55fa-869c-0f8479033c56)

A hand lightly touched his shoulder. Duncan started and the hot coffee burnt his fingers. It was Martin, his face grey and strained, the elasticated plastic hood of his forensic suit pulled down from his head.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Martin. ‘I didn’t mean to make you jump, but you didn’t answer the front doorbell.’

‘I … It’s okay, what did you want?’

‘I wanted to see how you are.’ Martin gestured through the window.

Down by the water, someone had drawn back the door of the main tent. Even at this distance, in the fading light, Duncan could see a glimpse of bare earth, cut away into different layers and trenches. It was a pitted labyrinth of mud and water, flags and poles numbered and labelled to match the records in the control tent.

‘Thank you for your patience with all this, especially in the circumstances.’

Especially in the circumstances. As if Duncan had any choice other than to tolerate the noise and disruption, the complete invasion of his privacy. In a bizarre way, he was almost grateful for that. The Barn felt empty without his family in it. His eyes slid back to the window, to the scene at the bottom of the field laid out like the trenches of the Somme. He nodded, only half aware of what he was doing.

‘Have you eaten?’ Martin said.

Duncan swung back to his friend’s face. With the hood down, he could see Martin’s damp wiry hair, speckled white at the temples, and his eyes, sharp and observant. Even with his obvious fatigue, Martin had the edginess of intellect and experience. Duncan had always respected that, but it also made him wary.

‘No,’ Duncan replied, his stomach rumbling.

Martin produced a couple of plump brown paper bags.

‘From the mess van,’ he said, nodding to the white van outside, with a generator of its own and a stench of fried chips. ‘They do a mean bacon cob.’

Already, Martin was pulling back the flaps of brown paper, tearing open a catering sachet of brown sauce and squeezing it over his food.

Bacon – there was something so vibrant about bacon. The smell of it, the taste of it, the sizzling as it cooks. Claire had been vegetarian. Duncan, too, when they were students. To Claire’s fury, it had been bacon that had broken his resolve, despite all his scruples.

‘Sure,’ said Duncan, giving in to his hunger and moving to join Martin. The two of them sat side by side on the kitchen sofa.

‘I never thanked you properly for looking after our cat,’ said Martin. ‘He’s doing well.’

Martin’s cat had been run over two months ago. Duncan had managed to save it, after wiring the jaw and removing one eye.

‘You’re welcome,’ he said. ‘He was lucky.’

The density of cat casualties never failed to enrage him – a quarter of a million of them each year in the UK, mostly people driving too fast, not caring at all.

‘Well, the wife was hugely relieved. He stays inside now.’

The one eye didn’t leave them with much choice. Duncan didn’t hold with keeping cats inside, but in this case, he’d had to make it absolutely clear.

‘Good,’ he said. The monosyllabic answer was all that he could manage. He took a bite of his cob.

Martin cast his eyes around the room. The heavy swathes of curtain fabric at the full-length windows by the sofa, the matching oversized lamps on the side tables on either end. The designer scented candles had not yet been burnt. It was Claire who was into burning candles. Duncan could see Martin assessing his taste, his wealth. Martin’s family still lived in a three-bed semi on a modern estate the other side of Derby. Some vets earned more than doctors, which spoke volumes for how people valued their pets.

‘You didn’t say much, yesterday.’ It was a question, not a statement. Martin squinted over his roll. ‘I know it was a lot to take in. Bit of a shock, especially … there’s not a huge amount I can tell you at this point, but is there anything you wanted to ask?’

Duncan folded the paper round his roll, tucking it neatly underneath. His eyes half-closed as he thought about it.

‘How was it found?’ he said.

‘Bob Shardlow found the remains, or rather his dog did. They were walking along the shore. It was half-submerged in the mud.’

‘What was Bob doing there? That’s my land on either side of the road, right up to the water. He’s got no business walking his dog there.’

Duncan knew that his annoyance might be seen as unreasonable in the circumstances, but he didn’t care. It seemed to him as if he shouldn’t care. About anything. That way was so much easier.

‘The path on the south side of the reservoir dam is blocked at the moment because of the high water levels and Shardlow had to find an alternative route.’

Duncan didn’t respond. He carried on eating, not looking up. Until:

‘Can you tell me anything about it?’

The body – they were talking about the body.

‘I can’t tell you that, I’m sorry, mate.’ Martin let his words fade away, using the excuse of the food to fall silent.

Duncan nodded – they both ate. For a moment, it was no different to the two of them sitting on the wall outside the school, or lying back against the grass on the slopes behind the swimming baths. It had been six weeks – he still felt numb. This new development was surreal. Duncan let it flow over him. He was aware of Martin watching him from the corner of his eye.

‘I’m okay, really I am.’

Duncan pushed the last of his bacon roll into his mouth and scrunched the paper bag in his fist. He kept his face studiously indifferent.

‘They’re good at their jobs, you know.’ Martin spoke gently. ‘We’ll do our best to keep this as quick and efficient as possible. But we don’t have much choice.’

‘I know.’ Duncan sat with the paper bag still in his fist.

‘I’ll keep an eye on things, I promise.’

‘Thanks.’ Duncan stood up to place the bag in the kitchen bin. His voice lifted. ‘I appreciate that. When do you think you’ll know more?’

‘Hard to tell at this stage. I’ll get an initial report from Forensics tomorrow. We’ll talk to you as soon as we can.’

There was another silence. Duncan moved to the sink. The cold-water tap gushed as he filled a glass, water frothing up and spilling out over the rim.

‘Right, I’m off now.’ Martin slapped Duncan on the back. ‘But I’ll be here again in the morning. You need anything, Duncan, anything at all, or anyone bothers you, you let me know, eh?’

‘Thank you, mate. I appreciate it. And thanks for the food. Have a good evening.’

Duncan turned to lean back against the sink, watching and sipping his drink as Martin left the house. When Martin had gone, he cast his eyes around the room, everything put away in its place, not a speck or a crumb in sight. He’d even had the granite work surfaces repolished. Already. He smoothed his hand across the top of the kitchen island. Claire would have hated it like this, too clinical – like a room at the surgery, that’s what she’d once said. But Duncan could do what he liked now, couldn’t he?

Now that she had gone.

CHAPTER 9 (#ulink_51a6161f-79bc-5b4a-803b-5f00c469a80d)

CLAIRE – BEFORE (#ulink_51a6161f-79bc-5b4a-803b-5f00c469a80d)

I’ve been sorting through my clothes all day today. One pile for the bin, another to give to charity. My arms ache from lugging stuff up and down the stairs, making the most of the time that Duncan’s out. He’s working late today, operating on the spine of a big dog. It could be a very late night, he’d said, don’t bother to cook for me. My head throbs. I’ve been fighting it all day, resisting the need for painkillers. I give in and head to the kitchen, rifling through a drawer for some pills.

I hear a bang. It’s a door upstairs. There’s the thunder of feet running down the stairs and Joe appears in the kitchen. He’s changed into jeans and a khaki-green jumper – the one his dad bought for his last birthday. The sleeves are already too short, but Joe still wears it, the sleeves rolled up irrespective of the cold so that no one will notice. He slams his body down on a chair, folding one leg over his knee so that he can put his trainers on.

‘Where are you going?’ I say. As if I didn’t know.

He lifts his head, defiance pulling his lips tight.

‘Out.’

He nods towards the metal detector leaning by the back door.

‘Please, Joe, not tonight. It’ll be dark soon. Why do you have to do this at night, for goodness’ sake?’

He stands up. My hand reaches across my chest for the soft spot in the hollow of my shoulder. I rub it as if it hurts. Joe balances on one foot and lifts his other leg, jamming the second trainer on, struggling to get his big fingers round the laces.

‘I told you – if the other guys see me, they’ll get there first, take whatever there is – we can’t let them do that.’

The ‘other guys’ – he means the metal detectorists. Treasure hunters. There’s a whole community of them, apparently; though I gather most of them are a lot older than Joe. It worries me, because it seems to me that my son doesn’t belong in such a group, not at this stage in his life. He should be out with people the same age as him, clubbing, drinking, meeting girls and boys and having fun. Not glued to online chat sites, poring over photographs of ancient treasure, participating in endless conversations about gold and silver coins, artefacts of the long dead, chasing stuff – stuff. It’s just a vain dream.

He stands upright and walks down the kitchen, opening and closing cupboard doors as he looks for food he can take with him.

‘No,’ I say, my voice firmer. ‘Not today, not tonight. I don’t want you going tonight.’

I stand with my legs apart, willing myself to look taller.

‘You listen to your mother, Joe. You’re not going out tonight.’

I swing round. It’s Duncan.

He’s come in from the hall and I stare at him in surprise. He’s home early. The operation either went really well or really badly. Or his latest girlfriend has blown him out and cancelled their plans for tonight. Our eyes meet briefly. It’s like this game between us – the texting and calls, all those late nights and excuses. He must realise I know he’s having a full-blown affair by now, even if I don’t know who. He’s been very careful about that.

He likes hurting me, letting me know in subtle ways how little he thinks of me, how meaningless our marriage has become. But never anything in public. He expects me to carry on, always has, because of Joe. He doesn’t know that I’m planning to leave, that I’ve been carefully saving, waiting, biding my time …

‘Joe! Did you hear me?’ repeats Duncan.

He’s in a foul mood. I can hear it in his voice. I flinch in spite of myself. He doesn’t care about Joe going out, he’s looking for another argument.

Joe acts as if he hasn’t heard either of us, still banging the cupboard doors like a drummer crashing on cymbals.

‘Joe! Stop that!’ Duncan’s voice fills the kitchen.

Joe stops and turns to face his father.

‘Why?’ he says. ‘Why shouldn’t I go out?’

‘You heard what your mother said. It’s almost night. It’s not sensible to go out in the fields at night. How can you possibly even see properly? Never mind this fantasy you’ve got of finding some kind of treasure hoard.’ Duncan stresses the word fantasy. ‘Enough’s enough, boy.’ Duncan’s voice deepens. ‘Your mother said no.’

Blaming me. As always, Duncan somehow makes me out to be the bad guy.

Joe riles at the word boy.

‘Fuck you!’ he shouts, stepping forwards to push past Duncan into the utility room.

‘Don’t you swear at me!’ says Duncan, bristling.

He moves to block Joe’s way, filling the door frame, holding one arm against the architrave. I see Joe’s eyes move to the metal detector propped up in the corner by the back door and my hand moves to my throat.

‘Please, Joe, let’s not do this tonight.’ I throw a warning look at Duncan. ‘Why … why don’t we go out for a meal instead? The three of us – pizza in Belston. You’d like that.’

He used to, when he was little. It’s been a long time since I went out for a meal with Duncan, let alone with Joe as well. Duncan looks at me, surprised at the suggestion, and Joe looks from one to the other of us, disbelieving.

‘What and watch the two of you fighting?’ he says.

I see the bitterness in his eyes. He bends down to duck under Duncan’s arm, but Duncan moves again, stepping forwards to meet him, one hand pushing against Joe’s chest. Suddenly, this whole thing has escalated to a physical confrontation. Joe bats his father’s arm away and I can see the indecision fly across Duncan’s face. Fight or let him go. There’s no winning that.

Instead, Duncan spins round and strides across the utility room to grab the metal detector before our son can get there. He snatches the battery pack that powers the thing.

‘I’ve had enough of all this. There’ll be no metal detecting for you tonight, Joe. It’s time you lived in the real world.’

Joe stands there, his face pale and stark. Like he can’t believe his father just said that, undermining the very thing that means so much to him.

Duncan marches into the hall. He exits the front door and it swings shut with a muted clunk. I hear the car door slam and the engine fire up. Joe is galvanised into action, growling almost like an animal.

‘Joe! He didn’t mean it!’

He ignores me. He takes the stairs two at a time. Moments later he comes down again, another battery pack in his hands. My eyes widen. I’d laugh if it wasn’t so upsetting.

‘Joe! You can’t!’

But it’s too late. He loops past me in the kitchen and grabs hold of the metal detector, fixing the new battery pack into place. He snatches at the back door. Arthur slips through the open gap to follow Joe. And this door slams with a proper satisfying thunk.

Joe has gone. Duncan, too. And I’m left standing on my own in the kitchen.

CHAPTER 10 (#ulink_2d844990-1c5a-59d0-8e58-25f33519f3cb)

CLAIRE – BEFORE (#ulink_2d844990-1c5a-59d0-8e58-25f33519f3cb)

I’m done with my sorting for a while. It’s frustrating, because I can’t pack properly till the very last day. Dusk has fallen early, the way it does in winter, and there’s a chill to the Barn despite our expensive underfloor heating. I decide to have a long, warm bath.

I head for the master en suite – it’s my bathroom now. There’s a freestanding contemporary bathtub in Apollo Arctic White that Duncan had placed right in front of the low window to make the most of the view. I run the tap for a while, strip off and lower myself into the water until it reaches my chin. The water is hot, turning my skin pink. Steam rises from my body, making me feel like one of those snow monkeys bathing in the hot springs of Japan.

The bath is huge. I slip further into it, until my head disappears beneath the water and I lie there, hair drifting to the surface, eyes wide open, staring up at the ceiling. I feel the warm clean bathwater lap against my knees. The future, Joe, my new home, that has to be my priority now. The thought of it rolls around in my head.

I let the heat seep into my bones, until my blood sings and my teeth part and I open and close my mouth, rising slowly up and down like a fish to breathe. Relax, Claire, relax. I finally let my thoughts drift.

Joe will come with me, I know he will – if he’s forced to choose, he’d rather be with me than Duncan. I hate that he’ll have to choose, but we’re not going far. I won’t deprive Duncan of his son, or Joe his father. Joe needs him, now more than ever. I’m hoping that afterwards, Duncan will make more of an effort, find a way to reach out and understand his son. A little distance can be a good thing, making you work harder.

It hasn’t always been like this – between Joe and Duncan and me. I remember Joe when he was about seven. He was just coming out of that baby stage, when all he really wanted was to be with his mum. Suddenly, he was discovering there was a world beyond my domain and asserting himself as a little boy. I’d felt an odd mixture of grateful relief and regret as he began following his dad around instead, like a mini helper.

There was a day when Duncan was chopping logs up from a fallen tree. We’d not long moved into the Barn and there were still piles of builders’ rubble scattered across the drive with a skip taking up the corner by the stone walls. There had been a big storm the night before. Leaves and branches littered the turf. The old oak tree in the top field had finally keeled over and Duncan had set up a workstation beside it and lit a small bonfire.

Curls of blue smoke drifted over our heads. I was breaking up twigs for kindling for the house and I thought Joe could help – boys and sticks are made to go together like bread and jam. But Joe was far more interested in what Duncan was doing. He was fascinated by the blade of the axe. Duncan stood there, sleeves rolled up, lean and fit. He’d swing the axe high over his head and then down to split the log end on. My heart was in my mouth. I was torn between admiration for my husband and a fear that Joe would step forwards into the blade at exactly the wrong moment. But Joe held back, re-enacting the arc of Duncan’s arms with his own as the pair of them swung in unison, Duncan with his real axe and Joe with his imaginary. It seemed to be one of those gentle outdoorsy afternoons, all of us in our own way working at the same task.

Until I realised that Duncan was in a world of his own, quite unaware of his son behind him. There was a grim expression of determination on Duncan’s face and each log was being split with ever more physical exertion, as if Duncan were taking out some inner fury on the wood. The last log bounced apart with such energy that one half exploded into narrow shards that almost flew up against Joe’s face.

I dropped my bundle of twigs and leapt forwards to pull Joe back.

‘Careful, Duncan – he’s right behind you!’

Duncan turned round to look, scowling at my interruption.

‘Then keep him out of the way. You need to look after him, Claire!’

Like it was my fault. I stared at him, willing him to understand. For once he seemed to realise. He lowered his axe, filled with remorse. He reached out to sweep Joe into his arms. Joe folded his limbs about his father’s body, one hand trying to grab at the axe.

Duncan set him down again, this time by the log. He pulled out one of the smaller pieces of wood and balanced it end up on the block. Finding a lighter splitting axe, he held it up to Joe’s hands and grasped the handle with him. He demonstrated the lift and blow, then stood back and let Joe take it. Joe pursed his lips, straddled his feet just like his father and raised his arms. Down came the axe. To his amazement, and I think Duncan’s too, it split perfectly in two. The grin on Joe’s face was one of those family moments.

I grieve for them both – Duncan, the husband, and Duncan, the father – it was always a bit hit and miss. He never quite got the hang of being a father. It was as if he was holding something back, like he didn’t quite believe he could be any good at it. Those were the good days, relatively speaking. It’s not like that now. I think of Duncan’s attitude earlier in the kitchen. It hasn’t been for a very long time.

I come up for air. The water swishes over the side of the bath, flooding the tiles beneath, soaking the pile of dirty clothes on the bath mat. I want to cry. But I won’t. Instead, I close my eyes and will it all to be over. For me to be already at the new house, Joe beside me, all my stuff moved without any arguments or upsets. Except I know it won’t be like that. It’s not like Duncan wants me, loves me anymore. God knows, he’s made that clear. But there will be consequences to our split. Financial consequences. The mortgage, the Barn, the pension – Duncan’s – our investment in the business, all of it will be at stake. Duncan’s reaction will be … The weight of all that fills me with trepidation and I feel the tension in me increase.

I push back into the water. I need to chill out, to calm down and get everything in perspective. I have to face it, unless I’m going to give up now and stay like this, trapped for the rest of my life. This move is for me. I’ve waited long enough. I’m not giving up or running away, I’m making a fresh start.

I sit upright, smoothing my hands over my wet hair. I reach out for the taps to top up with hot water. I feel the energy washing through my torso, my fingers buzzing, my toes wriggling, the skin on my face clean and bright. No tears, not today. Come on, Claire. I feel better, rational, in control. It’s a good feeling. And I should stop worrying about my son. He’s not a little boy anymore; he has to stand on his own two feet. I should trust him to be the adult he now is. I need to live in the present.

Can’t I do that?