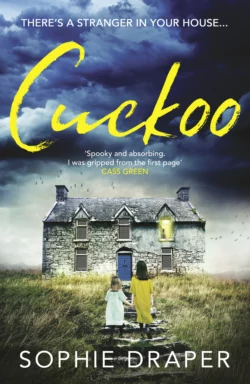

Cuckoo: A haunting psychological thriller you need to read this Christmas

Sophie Draper

Spooky and absorbing. I was gripped from the first page! CASS GREENThere’s a stranger in your house…When her stepmother dies unexpectedly, Caro returns to her childhood home in Derbyshire. She hadn’t seen Elizabeth in years, but the remote farmhouse offers refuge from a bad relationship, and a chance to start again.But going through Elizabeth’s belongings unearths memories Caro would rather stay buried. In particular, the story her stepmother would tell her, about two little girls and the terrible thing they do.As heavy snow traps Caro in the village, where her neighbours stare and whisper, Caro is forced to question why Elizabeth hated her so much, and what she was hiding. But does she really want to uncover the truth?A haunting and twisty story about the lies we tell those closest to us, perfect for fans of Ruth Ware and Cass Green.Readers love CUCKOO: ‘Spooky and absorbing. I was gripped from the first page’ CASS GREEN ‘A remarkably, taut and chilling debut. I absolutely loved it. Brilliant writing. All the creepiness. A heart-stopping ending’ CLAIRE ALLAN‘Sophie Draper is a remarkable new voice, combining beautiful writing with a gothic creepiness and a level of suspense which will keep the reader gripped to the end’ STEPHEN BOOTH'A brilliant, sinister debut that creeps under your skin and keeps you hooked until the shocking ending' ROZ WATKINS‘Wow! This is what a horror story is supposed to be! Super spooky and absolutely wonderful in all its gothic glory’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER‘The ending was amazing. Psychological fiction at its best. Five Stars’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘I never use the term "jaw-dropping" but it best describes the rest of this spectacular read!’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘Stands up there near to of the top of the pile with narratives like "The Woman in the Window" and of course "The Girl on the Train".’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘The ending BLEW. ME. AWAY. I feel like I’m going to have a book hangover now. SO, SO GOOD’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER

Copyright (#ub9f87679-3196-56d6-b574-aad6379c8172)

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Sophie Draper 2018

Cover design © Lisa Horton 2018

Cover photographs © Arcangel Images

Sophie Draper asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008311285

Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780008311292

Version: 2018-10-11

Dedication (#ub9f87679-3196-56d6-b574-aad6379c8172)

For my parents.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u0bf18e88-4d4c-5a56-b764-8577c2f08ad9)

Title Page (#u57860526-d0a7-553c-9452-f9fdc7fca5a2)

Copyright (#udcb423e1-f90c-5941-a8e8-a52a2a00ec4c)

Dedication (#u52e338c3-e970-505e-bf8a-12f28d55a255)

Prologue (#udef52aec-9240-59b4-b6d4-abbe281098fc)

Chapter 1 (#ue8b45127-08fd-5917-bb19-c53cc671226b)

Chapter 2 (#ue08a5a1f-1fa4-5765-8cea-99c3da6fca4b)

Chapter 3 (#u421ac1f9-0987-5f1e-91e6-74b23ed428ec)

Chapter 4 (#u6695ecbf-d68a-5546-b4e0-8caf3e953524)

Chapter 5 (#u9a4b632e-dfbc-50c0-b3e7-1e00b16bbefa)

Chapter 6 (#u94311033-3e10-5ef5-88a1-57b7e37ea5d9)

Chapter 7 (#u1c946deb-6c7c-551a-972d-04091e0bd78a)

Chapter 8 (#ub9d0cddc-51b8-544f-80b0-7a39f55cf4e5)

Chapter 9 (#uf1ce9855-23a7-5ade-b2fd-2e3f1d289bd7)

Chapter 10 (#u1e65a2ac-5918-5821-9dc1-48df39f2ce1b)

Chapter 11 (#uce81c665-b51b-5902-a54f-82c275480e16)

Chapter 12 (#u9a19dde3-3a64-5cf6-83b7-449cba12d145)

Chapter 13 (#ue0d680dd-c316-5c3c-a298-46bcd06393af)

Chapter 14 (#u49db506a-97ab-577b-bfd6-49f0f8798450)

Chapter 15 (#u0aebc527-af89-5503-8c0b-a18e68cdd03c)

Chapter 16 (#uea83cc41-1ca7-53dd-b031-e19508e964b9)

Chapter 17 (#ue17b285e-18b4-5853-bf4a-757b0f563c5c)

Chapter 18 (#u6cdb5930-469f-5ff7-9ba8-7ef3bbeb9f4c)

Chapter 19 (#ud5871bee-3520-5f2a-877f-defce52a7369)

Chapter 20 (#ue4a188e8-f136-5ed2-9354-3ac38ea67d44)

Chapter 21 (#u7377eb98-f89c-55db-85bc-518ea2b51659)

Chapter 22 (#uc7812828-45e8-54cb-87ee-021356cc2360)

Chapter 23 (#ue0314f32-8a6c-5ece-ad32-e82568271c4f)

Chapter 24 (#u6d5198be-3e3a-5c43-b2fc-28664f6864bd)

Chapter 25 (#u9715aee4-3b74-55d6-81ed-4b71b9c595d5)

Chapter 26 (#u334ace8f-f832-5b75-b5cd-1a1f6dfce919)

Chapter 27 (#u4d094841-d27b-5f91-8fa6-ca74efba2485)

Chapter 28 (#u575ce214-a31f-5f6d-abae-4cc25db8d731)

Chapter 29 (#u0f1b0237-277d-5285-acfc-fa8d653bc601)

Chapter 30 (#u49b00f80-6f6c-58b1-b75f-5f2aab8bb232)

Chapter 31 (#udb61f0e8-6814-5bde-b51c-b32ebd46d44f)

Chapter 32 (#uf4cc248a-cb6b-5027-b6f7-b62f55f6dd0e)

Chapter 33 (#ucb045dbc-1d5d-5a05-9bd5-b09628fe195f)

Chapter 34 (#ua639d54c-d643-52a8-b289-98ec67c243d3)

Chapter 35 (#u4ab5807f-9b1e-561c-8455-5cb129d28cee)

Chapter 36 (#u0eb1dffc-9781-5bbd-b255-c5b09fb2f670)

Chapter 37 (#u8b889cb5-749c-513d-abea-13b9aea93702)

Chapter 38 (#ueee2087c-fc6a-54ff-95c1-a2a37987dfe4)

Chapter 39 (#u9f9c5df6-3405-5b37-9f49-ff73813d2e69)

Chapter 40 (#u1c9e2731-2d87-50ea-8ac7-9aaf1dcd9874)

Chapter 41 (#u59a73597-6a13-5e65-b11e-642a2e3e3528)

Chapter 42 (#u1921a42e-5470-58ab-aa98-0ff932c17034)

Chapter 43 (#ub13eef46-d01b-59da-bbd0-17ce51ce4375)

Chapter 44 (#u4376a9b5-ca43-5d9b-8afd-f4a4b5a0a213)

Chapter 45 (#u16d9c2ad-2048-59f0-85ed-24c13c75ea90)

Chapter 46 (#uee3b0138-8e82-58cd-b904-8be497f81f28)

Chapter 47 (#u50ca5169-a35f-5f1e-9041-ee214cbe6007)

Chapter 48 (#u5b0f95db-1bdd-57bf-b826-af88aaf5c210)

Chapter 49 (#u794fcc54-b0b7-5169-8978-815aee684e41)

Chapter 50 (#u7790f8cf-327e-5681-a586-633bdd6cc3ca)

Chapter 51 (#uaddbcef9-7b08-529c-af8b-b30beb67fc1f)

Chapter 52 (#u3fc23052-422c-5ef7-b562-efc407c42649)

Chapter 53 (#ua60059d9-6f92-5bce-b842-49322f57ba27)

Chapter 54 (#u417a92d2-e266-509b-b568-2687ed7b0710)

Chapter 55 (#udab7c9c4-c932-5e73-b18d-76c002c80280)

Author Note (#ueb34c6d0-40e1-5458-a4bb-02751e2a48c5)

Acknowledgements (#u495e9b9f-4e1e-5590-baa0-28ae1cb7909f)

About the Author (#u516e9d51-2158-573f-8029-162ed6315655)

About the Publisher (#u4652ba01-ac9c-5134-a611-a5e54ce36eda)

PROLOGUE (#ub9f87679-3196-56d6-b574-aad6379c8172)

I am floating between two worlds, the living and the dead. As I lie here in my hospital bed, the faces shimmer above, voices distant and unfamiliar.

Slowly I return. I cannot move. I am a doll, placed exactly as they choose. They’re quite unaware that I’m awake, that I can see and hear – the machines, the trolleys on their wheels, the tubes wriggling from body to bed, the clicks and beeps that mark each breath, each beat a ticking clock, each sigh discharged as if my last.

Today I can see the table. Someone places a small painting beside me. It shows a boy. He sits on a grave under a tree, ivy coiled around his feet. He holds a pear drum.

I know this object. Not a drum, but something else. The shape appals me, a large pear-shaped box, too big for the boy’s lap. The strings that stretch across, the handle at one end, the strange creatures painted on the side. An instrument. It plays the devil’s music. My heart jolts, leaping against my ribs, hammering like a condemned man. The machines fill my lungs with air. I feel my chest expand, stretching until it is so taut I think my body will burst. But no, the machines deflate. Once more I hear their steady beat. I watch the drip, drip of the feed that punctures my arm and my consciousness fades away.

When I wake, I hear hushed tones, regret. They’re talking about me. My mind is surging, willing myself to move, to make one small sign that I’m alive. But the feeling dissipates like smoke in a chimney. I watch the boy. He winds the handle on the pear drum, round and round …

The hours turn into days, then weeks, time sliding between each heartbeat. Slowly memory returns. When I see the sky, it’s white or grey, reflections of the room bouncing off the window glass. And black. Sometimes against the grey is the tiniest streak of black, one small bird buffeted by an invisible wind.

As I lie in this bed, they all think I am as good as dead.

Except I am not dead – not yet. How disappointed they must be.

CHAPTER 1 (#ub9f87679-3196-56d6-b574-aad6379c8172)

She was watching me, my golden sister. Her eyes were dark; her hair long. She stood opposite me on the far side of the grave.

The black earth stained my fingers. I folded them in as if to hide the weight of the clump of soil sitting in my hand, damp and clammy against my skin.

My sister had come, despite all expectation.

She held her head upright and her gaze was unwavering. The flaps of her calf-length coat were caught by the wind, revealing a flash of red, her dress, her perfect legs sliding down into perfect shoes, heels sinking into the thick grass. I pressed my lips together and lowered my head. She was like a designer handbag lit up in a shop window on the King’s Road, glossy and beautiful and out of reach.

My stepmother’s funeral was a quiet affair. The small churchyard clung to a slope on the edge of Larkstone village, gravestones like broken teeth, the surrounding hills of Derbyshire cloaked in a fine drizzle that seeped through the thin cloth of my coat. There were a few neighbours, a bearded man standing on his own and an older woman dressed in black silk. I felt as though I should know her. I tilted my head. Her husband stood behind with an umbrella slick with rain and she turned away from me.

And there was my sister, Steph, in her red dress. She had bowed her head too and I could no longer see her face. The wind blew my hair over my eyes, tangling against the wet on my cheek. I let my eyelids close.

I flinched as that first clump of earth hit the coffin below.

I tried to concentrate on the vicar’s words, his voice. I took a peek. He held his prayer book with hands that were open and expressive. His skin was smooth and brown and he spoke with a clear, cultured accent. Not a local. I wondered then what the village thought of him. I wanted to smile at him, but he was too engrossed in the service. As I should have been.

‘Let us commend Elizabeth Crowther to the mercy of God, our maker and …’

Crowther. It still hurt.My stepmother had taken my father’s name, my mother’s name, along with everything else.

‘… we now commit her body to the ground: earth to earth …’

Another clod of black sodden earth hit the coffin. I reached forward and opened my hand.

‘… in sure and certain hope …’

What hope? My lips tightened. I was not, had never been, a believer.

‘… To him be glory for ever.’

More earth tumbled down into the grave. The vicar lowered his head again, we all did, as he intoned a prayer. I kept my eyes open. It was cold, the air spiced with rotting leaves and autumn smoke. A single bee struggled against the wind to land on the cellophaned flowers at our feet. It looked so out of place, late in the year. I watched it hover, a dust of yellow pollen clustered under its belly, tiny feet dangling beneath, oblivious to the drama playing out above.

I risked another look at my sister. I felt a kindling of old fear. She lifted her head and our eyes met and I drew a staggered breath.

Steph.

The back room of the pub was half empty, the walls a dank musty brown, the ceilings punctuated by low beams riddled with defunct woodworm holes. Decorative tankards hung like dead starlings from their hooks and beneath, a cold buffet was laid out on white linen with the usual egg mayonnaise sandwiches and hollowed-out vol-au-vents. An elderly neighbour cruised down the table with its foil trays, prodding this and that as she loaded up her plate.

My sister kept her distance, nibbling on a sandwich, talking to the vicar. A stack of blackened logs in the grate behind them spat and hissed without any sign of a flame. Her blue eyes fluttered across me as I stood on the other side of the room. She was waiting, I realised. Waiting to see what I would do.

I felt my chest tighten, the hands at my side clench. I thought perhaps I should forgive her, that I should be the one to go over and talk to her. Beyond the function room, I could hear the bellow of a man at the bar, the recurrent beeps of a slot machine by the entrance and the slash of rain battering the front door as it juddered open and closed again.

‘Hello,’ I said as I approached. My voice was husky and unsure.

‘Caro.’

Her voice surprised me. It had a distinctive New York drawl. The tone was gentle. If it was meant to encourage me, it had the opposite effect. I didn’t reply. I could hardly bear to meet her eyes. The vicar moved on, scarcely acknowledging me.

Then Steph put her glass down. Her body relaxed, her arms opened. I wanted to step closer, but my feet refused to move. We hugged, a loose, cautious kind of hug, her pale, flawless cheek brushing cool against my skin.

‘I didn’t think you’d come,’ I said.

‘I almost didn’t, but then I thought, why should I let her stop me? She’s gone.’ Those long vowels again, so alien to me. But then it had been many years since I’d last heard her voice. ‘And I wanted to see you. You’re my sister.’ Steph’s expression was cautious, assessing my response.

‘I … I …’ Now I was her sister?

‘I’ve seen your website, your illustrations. They look amazing!’

‘Really?’ I said. I pulled myself up, keeping my tone light and neutral.

‘Yes, really. I love The Little Urchin, with her spiky hair, her nose pressed up against the window.’

My latest book. It was a compliment. I hadn’t remembered her ever giving me a compliment, not when I was little. But Steph’s face was open and sincere. She was different to how I remembered. I wanted to believe.

‘You’re very talented, you know, I always knew you would be creative,’ she said.

‘Oh, well, um …’ Praise indeed, to hear that from my big sister.

‘I mean it. I could never do something like that.’ She smiled. Her arms waved expansively and her coat parted, another glimpse of red.

I shrugged. ‘Thank you.’

She’d cared enough to look me up, when had she done that? It was unexpected. I was suddenly conscious that I knew very little about her, what she did for a living. Was she married? Did she have children? I didn’t even know that. She was seven years older than me and it was quite possible that she had a family of her own by now. I eyed her flat stomach, the clothes. No, I thought, no children. Somehow, I couldn’t see her with children.

A movement caught at the corner of my eye, the curtains at one of the windows flapping in a draught from a broken pane.

‘Can we go somewhere else?’ Steph’s voice dropped. ‘Anywhere you like, but not here.’

I swallowed. It made sense to refuse, my head screaming at me to walk away. It was almost twenty years since she’d left home, when I was nine. She’d been sixteen. We’d had no contact at all since then, despite all my attempts to stay in touch. Christmas, birthdays, they’d meant nothing. Perhaps my early cards had ended up at the wrong address.

But I wanted to. I really did.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘I got a job at a hotel in London, manning reception.’

My sister’s voice was measured and quiet. I could imagine her smart and sleek behind a desk.

We’d found a café in the small town of Ashbourne a few miles away. The smell of freshly ground coffee beans and vanilla seedpods cut across the muted chatter in the room and I lifted my cup to hold its warmth against my fingers.

‘Then they offered me a job in the marketing department.’

She flicked her hair across her shoulders. Blonde, but no roots – it had been brown when we were young. She must have dyed it, I thought.

‘I moved to Head Office and worked my way up. Then I joined the US team. I’ve been based in New York now for six years.’

There was a pause. Her eyes travelled across my thin, gawky frame. Six years. In New York. Yet there had been so many more years when she’d been in London, in the UK. Close enough and yet so far. I didn’t reply, struggling to find a common ground.

We both took another sip from our respective drinks. The traffic beeped through the glass window, a sludge of rainwater washing onto the pavement, green and red traffic lights reflected in the puddles. Colours, I saw everything in colours.

‘And you? Where did you study?’ Steph leaned in over her cup.

‘Manchester. Art and Creative Design.’ I tucked my fingers into the palms of my hands, feeling my short nails scratch against my skin.

‘Really? I somehow thought you’d have gone as far as possible from Derbyshire.’

I bristled. Manchester was only an hour and a half from the village by car, but by bus and coach it was much longer, and you still had to get from the house at Larkstone Farm to the village bus stop. Manchester had seemed a million miles away. The bustling big city, new people, a whole new life.

‘Did you enjoy it?’ she asked.

‘Yes, I did. The course was brilliant.’

I side-stepped the truth: my self-imposed isolation; my lack of confidence; my distant manner.

‘I’m glad.’ Steph stretched out the fingers of her hand, wriggling each one before folding them back into her palm.

There was another silence.

‘And now you’re in London. Bet it’s nice being self-employed, working whenever you want.’ She smiled encouragingly.

‘Hmmm, depends how you look at it. There are so many other illustrators out there, vying for the same jobs for not much pay. It’s not an easy way to make a living.’

Already I was saying too much, filling the space with words, justifying my own ineptitude. Why should I feel defensive?

‘I can imagine.’ My sister nodded, sipping her coffee again. There was a soft chink as she placed the cup carefully back on its saucer. A waft of perfume made me lift my head up. I wasn’t a fan of any kind of perfume.

‘How did it happen?’ Steph’s voice broke.

I flashed a look of surprise at her. Did she even care? I scanned her face, the perfect arch of her eyebrows, the smooth forehead, no lines, as if she never frowned, or even smiled. Like a Greek statue, head turned away, poised in her indifference. Except … the voice was at odds with her face.

‘They didn’t tell me anything,’ she said.

It had been the family lawyer who’d made the call to her. I felt a pang of guilt.

‘I’m sorry I didn’t ring. But I didn’t have your address or a telephone number. It was the lawyers that tracked you down.’

They’d organised the whole thing, the funeral, the reception, much to my relief. They’d rung me too.

‘That’s alright, I understand.’ Steph watched me still, ignoring the implied criticism, waiting for an answer.

I threw a glance at the neighbouring tables, but the occupants were all too engrossed in their conversations to pay any attention to ours. I drew a breath, bringing my hand up to my head, thrusting my fingers into my hair.

‘I … that is, she … she fell,’ I said. ‘Over the banisters from the first floor. Some time during the morning, they said, though apparently she was still in her dressing gown.’

‘How could she fall over the banisters?’ Steph asked.

‘I don’t know. Some kind of accident, I was told. She was found face down on the rug in the hall below. Broken neck. Bit of a mess.’

I thought it best to stop there.

‘Ah.’ Steph hesitated. She cast her eyes to her lap, folding her napkin.

Then she reached out a hand, covering my own. ‘So, it’s only us now.’

I nodded. My eyes searched the fine cracks on the back of her hand. Expert make-up could disguise an older face, but not the hands.

‘Yes,’ I mumbled. ‘It is.’

‘I’m in London after this, for a few weeks at least, in a hotel near Tottenham Court Road.’ She drew a breath. ‘Can we start again?’

I looked up.

‘It’s been too long, I know.’ Her hand was cool over mine, her face earnest.

I held my hand still, resisting the urge to move it. I really did want to believe this different Steph. What had happened to her? I’d never understood whatever it was that had gone on between us. Or between her and Elizabeth.

Her eyes held mine. They were blue. Mine were brown. The street lights wobbled in the wet glass of the café windows, amber yellow.

Steph’s lips parted.

I nodded again. ‘Yes.’

I thought of my stepmother. I tried to picture her body lying on the hall floor. The blood smeared on her lips, pooling on the rug, her red-painted face still smiling, as if to say, as she’d often said:

‘Shall we start again, Caroline?’

CHAPTER 2 (#ub9f87679-3196-56d6-b574-aad6379c8172)

The phone rang.

‘Caro?’ It was Steph. She’d promised to ring before she left the UK. I was back home in London and hadn’t heard a thing for days and now suddenly there she was.

‘Hi.’ I could hear crackling over the phone line.

‘Fancy a curry? My treat.’

I caught my breath. ‘That sounds great. When?’

‘Tonight? We need to talk.’ She named a restaurant.

‘Sure, what time?’

‘Seven.’

‘Okay.’

I put the phone down slowly. It felt strange talking to my sister like that, as if we were friends.

We met up, Steph and I, in a curry house behind Leicester Square. We chatted about not very much, avoiding anything to do with the funeral or our childhood.

‘My office is amazing, in one of those skyscrapers overlooking Central Park. I thought I’d faint when I first looked out of the window and realised how high we were!’

I found myself following each word, each lift of an eyebrow, each smile, wondering what Steph was really saying as she talked about her work, her apartment in New York, the glamour of Fifth Avenue boutiques and constant traffic, flashing advertising boards leaching light into a sleepless city sky. Look at me, she was saying, how fabulous my life is, how lucky I am – unlike you, my little sister. That’s what she was really saying, wasn’t she? I caught my bottom lip between my teeth. I didn’t want to feel like this. I wanted Steph to be my friend, to be my sister.

It was the end of the meal when Steph finally brought it up.

‘What about the house?’ she said.

‘Larkstone Farm?’

The house where we grew up. I couldn’t call it home. The waiter was hovering, leaning in to whisk away a plate, his eyes sliding down towards Steph’s long legs.

‘Yes. It’s sitting there empty. It’s not good for the place. And someone’s going to have to go through all that stuff, sort out the paperwork, ready the house for sale. Unless you want to move back up there?’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘It’s ours. Except I don’t want it. Why would I ever want to go back to that place!’ She sounded bitter. ‘Besides, my home is in the States now. I’m seeing this guy … But you – you could go back and live there.’ She hesitated. ‘If you wanted.’

‘Ours? I don’t get it. I mean, Elizabeth had a cousin, didn’t she? It wouldn’t come to us, surely? We were only her stepdaughters.’

‘No, that’s not how Dad arranged it. I went to see the lawyer. When Dad married Elizabeth, he set up a trust. Elizabeth didn’t own the house after he died. She had use of it whilst she was alive, but it reverts to us on her death.’

My sister’s words sank in. And then the thought flashed into my head: she’d been to see the lawyer, on her own? But then hadn’t I been avoiding it myself? I hadn’t wanted to think about the house, all that stuff that had once been Elizabeth’s, that had once been my dad’s.

‘We’ll inherit the house?’ I said. The two of us?

I sat up. I couldn’t quite believe what she was saying.

‘Yes. Except, like I said, I don’t want any of it. It’s been on my mind a lot ever since I found out, I didn’t know what to say to you. But I realise now that I really don’t need it. My life’s in New York and I have more than enough money. It’s the least I can do. Besides, the funeral was bad enough, I couldn’t bear to go back to the house itself, even for a short while.’

She fell silent. There was a moment when I thought she was going to say something else.

‘I don’t know what to say.’ My eyes searched hers.

She shrugged and then smiled.

‘It’s not much of a place, as I recall – probably in desperate need of attention, in the middle of nowhere. I don’t have time for a project like that. It’s yours, honestly. Sell it, keep it, rent it out, move in. I don’t mind. Whatever you want to do with it.’

Larkstone Farm. Compared to London, it was the middle of nowhere. In the wilds of Derbyshire. It wasn’t a working farm, not any more; I couldn’t remember whether it still had any land. Steph leaned across the table and topped up my glass of wine.

But live at Larkstone Farm? It seemed incredible that this should happen right now. I was effectively homeless, bunking down with my friend Harriet, except she’d already left for her new job in Berlin. I had a few more weeks till the notice on her flat ran out. She’d done me a favour, but I was still struggling to find somewhere else affordable.

‘I …’ I tried to gather my thoughts. ‘What did the lawyer say, did you tell him?’

‘I did. It’s entirely up to us what we do with the place. But whether you move in or sell up, it has to be cleared of all her stuff. And someone really should be there whilst that is happening, if only to keep an eye on things. If you want it, it’s yours, that’s all I’m saying. And I’d be glad not to worry about it.’

My mind leapt ahead. I could sell it, buy something smaller, closer to London, giving me some cash to fall back on when the commissions slowed down. Or I could live there whilst I decided what I wanted to do. Now that Elizabeth was gone, why shouldn’t I stay there? It was just a house. To live rent-free would be a huge relief. Did Steph really want to waive her inheritance?

And besides … Maybe I needed to go back, to see the place just one more time, to put the past behind me once and for all. Elizabeth was dead. I was never going back to Paul and I’d had more than enough of London with its sky-high rents and unaffordable houses. I could work wherever I was, couldn’t I?

The thought was exciting, the timing perfect.

‘Why don’t you think about it?’ said Steph.

Elizabeth had married my father when I was a baby, not long after my real mother died. I should have been young enough to think of her as my mother, but somehow I never did. She used to say how I screamed and screamed in her arms, wriggling to get out. Perhaps it was my fault. I had rejected Elizabeth before she’d ever rejected me. Then my father had died too, barely four years later, leaving Steph and me with Elizabeth, growing up at Larkstone Farm. Just the three of us.

As I sat at my painting table, back in Harriet’s basement flat, I could hardly bear to dwell on it. The house, my childhood, my old life in Derbyshire.

I looked up through the window, the one that faced the street. I could see the feet of the passers-by, boots and shoes slapping against the pavement, buggies rolling in the wet, listening to the steady swish of cars cruising down the road. The temperature had dropped since the funeral at the beginning of the month, the first bite of winter in November – so early.

Derbyshire was something I’d pushed to the back of my mind. There, where the rain fell straight and sharp, like needles on your back, punishing. In London it ran along the paving slabs, splashing into gullies, a smooth plane of water brimming with dirt, lapping at your feet. I’d never gone back, not after that first day I went to university. I’d never wanted to go back.

The laptop to my side chimed. I couldn’t resist a quick check. London, it was the life I’d chosen to lead, but it was hard being on my own, here in the midst of all these people.

It was an email from David, my agent.

Dear Caro. Great news, you’ve had an enquiry for a commission to illustrate for Cuillin Books. It’s a collection of fairy tales. Now that should be right up your street. The brief and the text are attached. You’ve got about three months to do it. Let me know what you think? D.

I wriggled in my seat and tapped a reply.

Dear David, that sounds promising. I’ll take a look and let you know.

I liked to play it cool, but the truth was it was unlikely I’d have turned it down, whatever it was. Fairy tales, though. He was right about that; I had a soft spot for fairy tales. I clicked on the file. Then I saw the title.

The Pear Drum and Other Dark Tales from the Nursery.

The Pear Drum.

My fingers halted in mid-air. I felt my stomach heave. It filled my head; the words, each letter a different colour like bulbs around a make-up mirror. And the thing itself, as vivid as the day I first saw it, my stepmother’s pear drum.

I snapped the laptop lid down onto its keyboard, stood up and walked away.

Later, I tried to view it dispassionately. The Pear Drum and Other Dark Tales from the Nursery. It was an odd title for a book of fairy tales. A bit of a mouthful and not the kind of thing you’d give to a young child. It seemed strange that it should appear in my inbox now, after Elizabeth’s funeral, prodding my memories of the past.

I closed my eyes, the words leaping out at me despite my attempts to distance myself. Pear Drum.

The pear drum was something I had deliberately buried in the past. But it was always there, a part of me I could not shift, hidden in a corner of my consciousness. Perhaps that was why I’d ended up in London – as far away from Derbyshire as possible. I was beyond that now. Time had passed.

I would have been about six years old when I first saw the pear drum. I wasn’t sure. The memories of my childhood had always been patchy, especially those first years. But this was perhaps my earliest memory. It was like a black curtain – before the pear drum, after the pear drum. I tried not to think about it too much.

We’d just come home, after some kind of family gathering. Elizabeth was dressed in black linen, pearls about her neck. Elegant – she’d always been elegant. She’d dropped her handbag onto the hall table and grabbed my tiny hand. She pulled me into my father’s old study, long painted fingernails overlapping about my wrist. The room was at the back of the house, behind the stairs. I knew it had been my father’s room from the pictures on the wall, the bookcase and the desk by the window. An armchair was positioned beside the fireplace, the stove blackened with age, the iron griddle top layered with dust. My stepmother didn’t normally use this room.

In the corner furthest away from the window stood a crate, large enough to hide a child in. I pulled back, reluctant to let myself be dragged any further.

‘Stop that caterwauling, Caroline!’ I must have been crying already. ‘It’s time I showed you something!’

Elizabeth let go of my wrist and I stood there shivering, the scent of her perfume conflicting with the lingering smell of old leather and damp unloved books. She was already dragging the lid of the crate open, fingers pulling at the double catch, resting the weight of the lid against the wall. Her arms reached inside and I swear I thought there was a dead body within.

But what she brought out from the crate was the pear drum.

It wasn’t a drum at all. It was like a mechanical violin, or ‘hurdy-gurdy’. Its real name, as I discovered later, was ‘organistrum’, but Elizabeth had always called it her pear drum.

It had a pear-shaped body with strings and a broad, oversized decorative arm. At the wide end was an S-shaped handle which turned a wheel against the strings. But the arm was actually a box into which the strings disappeared. It could be opened to reveal the workings inside, the keys, the ‘little people’, my stepmother had called them. Pressing down on the pegs alongside the box made them dance, creating the notes.

She adjusted the shape of the thing onto her lap as she sat down on my father’s old chair. It was so big each end rested on the chair arms on either side of her. She began turning the handle and the thing fired up. I almost jumped at the sound. It was a drone, hesitant at first. It got louder, a vile, screeching sound that filled the room, forcing me to step back and clasp my hands against my ears. But as I listened, the sound consumed me; loud as it was, it was seductive too, a slow lingering melody filling the room.

It was the weirdest kind of musical instrument you could ever have thought of. But the pear drum wasn’t the problem. It was the story that went with it.

CHAPTER 3 (#ub9f87679-3196-56d6-b574-aad6379c8172)

The M1 stretched out in front of me – endless tarmac, sweeping clouds, the trees bordering the roadside skeletal black. London was behind me. It hadn’t taken so long to leave.

It should have surprised me, the ease with which I’d turned my back on so many years in London. Except it did not. Never mind Paul, it was as if I’d been waiting for an excuse, my sudden inheritance prodding my inertia. I’d been in London seven years – didn’t they say that life moves in cycles of seven years?

It wasn’t like anyone was going to miss me. Not Paul at any rate. He and I were done and I certainly wasn’t going to miss him. I missed Harriet, though – I’d just started to get to know her. We’d met at my first public exhibition. She’d been loud and brash and I’d been quiet and shy. She’d made me laugh and she’d said my paintings made her cry. She’d been the voice of reason telling me to get out of there when things had gone so badly with Paul. Her generosity and kindness when I’d needed somewhere to go wasn’t something I was used to. I’d never told her about Larkstone.

She’d been full of remorse over her job in Germany.

‘I can’t leave you like this,’ she’d said.

‘Yes, you can,’ I replied. ‘Absolutely, you can. I got out of there and I have a new life. You’ve been amazing, but now it’s your turn to follow your dreams.’

Harriet had been offered a job in a gallery in Berlin, a chance to experience a new country, to take her own work in a different direction – how could she turn that down? Perhaps that was why the time was right. I had a few friends, work contacts, fellow artists I’d met like Harriet, but no one close. I liked it like that. In an odd sort of way, I was glad she was gone. It was easier keeping people at a distance. I completely understood why Steph had ended up in New York and had never wanted to go back to Derbyshire.

But meeting and getting to know Harriet had made me think. She wasn’t afraid to start again. To brave a new life, to put the past behind her. Leaving the noise and traffic of London felt to me like a snake shedding its old dead skin. I’d packed up everything I had, handed in Harriet’s keys, and here I was, on my way to Derbyshire. I had a new commission to work on as well as the house clearance and, for the moment at least, it was to be my new home.

I lifted my back, flicking on the windscreen wipers as sleet began to slap against the car windows.

Eventually, I turned onto the dual carriageway that led into Derby. The sleet and rain had stopped and there was a break in the clouds through which the sun shone, lighting up the roofs of the houses. The city was a tangle of incomprehensible ring roads and roadworks, but twenty minutes later I was free of it, heading down country lanes, chasing the shadows of the growing dusk.

The village of Larkstone was quiet, a few rainbow Christmas lights blinking on the street. I drove slowly, looking for the right turning back into the countryside. A couple of pedestrians dived across the road, heads bowed against the wind. It was even colder now that the brief sun was lower in the sky.

Someone beeped from behind. A man in a muddy jeep. He was far too close. He beeped again. I touched the brake pedal, enough to trigger the lights. It had the desired effect. In the mirror, I saw his hands gripping the steering wheel, his face scowling. A woman on the street stopped as our two cars drove past. Her expression was fierce, it took me aback, until she broke into a smile, waving at the man in the jeep. I carried on. I felt a surge of satisfaction as the jeep was forced to follow me out of the village, tailing me for a couple of miles until I slowed for the house. The jeep growled up a gear, swerving around me as it accelerated away and down the lane.

The house was at the end of a track, on a hill overlooking the valley. Tall chimneys stood proud against an unexpected blazing sunset sky. I peered through the windscreen, my teeth catching on my lower lip.

It was a tall building, hewn from thick Derbyshire stone, part farmhouse, part fortified manor house. The second-floor windows were tucked in under the eaves and one small attic window peeped out from the tiles above. All the windows were an empty black, save for a glint of red at the top where the last rays of the sun reflected off the glass. A low wall enclosed the front courtyard and two semi-derelict outbuildings sheltered behind. I drove the car forward the last few metres, its wheels skidding over the gravel, spitting stones as it came to a halt.

I sat in my seat, watching the last of the daylight playing on the colours in the stone. Already a picture was forming in my head: the house inked out in black lines on its hill, angry colours exploding in the background, windows like bullet holes peppering the walls. My fingers itched to draw. I felt a strange kind of lift. The house, its history, its memories, it was like I needed this. Elizabeth’s death was a fresh start, for me and Steph, and the house.

I slammed the car door shut and searched in my handbag for the key the lawyers had sent.

Something soft touched my ankles. I yelped in surprise. It was a cat, her head rubbing against my legs. I reached down and she seemed content to let me draw my fingers through her fur.

‘Hello there, Puss.’

She was small and black, save for a single white sock on her front paw. Half-starved by the look of her. I made to pick her up but that was too much. She skittered away, jumping onto the wall to look at me reproachfully.

‘Okay, fair enough,’ I said, fingers finding the keys.

I swung round towards the house. Water stained the front step and dripped from the leaves of the shrubbery around me. A security light bounced on as I stepped up to the door and the key turned smoothly in the lock. The house, it seemed, didn’t know whether I was friend or foe.

It smelt stale as I entered. I snapped the switch on the wall. The hallway was instantly familiar, the smell, the clock, the objects around me. The walls were lined with paintings, scenes of rural Derbyshire, the crags at Mam Tor, a pheasant stalking a field; it was all as I remembered, except somehow different. There was a space on the wall marked by a dirty grey outline where a picture had once hung and the hall table with its two drawers was thick with dust – even the cut-glass bowl that sat on top was grimy with dirt. How long had it been like that? Longer than the six or seven weeks since Elizabeth’s death in the middle of October. The house mouldered in genteel neglect and I felt a prickle of unease; my stepmother had been fastidious in her housekeeping when I was younger.

Two rooms led from each side of the hall and a wide staircase hugged the back elevation. A tall window overlooked the stairwell and my eyes were drawn to the banister above. Its richly polished wood curved up to the first and second floors. A patterned rug sprawled on the stone floor beneath, a rust-red stain at its centre. I felt my chest contract. Why hadn’t someone taken it away? It was a stark reminder of the manner of my stepmother’s death.

I wondered how she’d fallen. With a piercing scream, or a silent thud? They’d said it had been an accident. Had it been a sleepless night blundering in the dark? No, hadn’t they said morning? I couldn’t imagine how someone could fall over a banister. They’d also said there’d been signs of excess alcohol in her system. When had Elizabeth started to drink? I tried to feel sympathy for her, gawping at the stain, fascination and horror holding me still, the rug a simple testament to Elizabeth’s death.

I moved forwards, snapping on all the switches I could find, flooding the house with light, determined to chase away the ghosts.

An hour later the Aga in the kitchen creaked as heat seeped into its old bones. A table dominated the room, perfect for painting. I slung my last box onto the wooden worktop. Fishing out the contents – tubes, brushes, small tins and cloths – I lined them up like precious toys, spacing out each item. Next came the laptop, phone, dongle and printer, juggling cables until they trailed across to the sockets and my emails filled the screen. A welcome connection to the outside world. Not quite so alone.

I returned to the hall. All my possessions stood in pathetic isolation, dwarfed by the grandeur of the house and the triple-height ceiling over the stairs.

In the sitting room I found Laura Ashley florals, scented candles and a TV. This was where my stepmother sat, on the big sofa, her favourite blanket neatly folded on its arm. I snatched it up, striding from the house to dump it in the bin. Adrenalin fired in my veins. I swept through the entire ground floor, harvesting photos, magazines and papers, soap and towels, even a stray cardigan from the kitchen, still smelling of her – I held it between my fingers and dropped it into a black bin bag as if it were contaminated.

I had to drag the rug from the hall out the front door. It was a heavy wool and felt as if a body were rolled up inside. The thought was almost comical, except it made me nauseous. I felt guilty, as if it were my fault, as if I’d killed Elizabeth myself and was now removing the evidence. It made no sense, but the feeling was there, with every item that I found, soiled by her touch, her scent, her sweat, her very blood.

The purge had only started, but it was enough for now. The rest, including upstairs, would have to wait. I scrubbed my hands, ate the remains of a pot of salad, fetched my duvet and climbed onto the sofa. I tried to sleep, lying there too aware of the size of the house, the emptiness of the rooms above my head, the wind whistling at the windows outside and the clock ticking in the hall.

The cat was there again in the morning, sitting on the window sill outside. Behind her hung a pall of winter mist. She watched me through the glass. I pretended not to notice. Her head turned as she tracked my movements, her eyes blinking with curiosity. I scrounged a cup of coffee from a jar in the kitchen, standing in the midst of more of Elizabeth’s stuff, things I’d missed the night before – a basket of unwashed clothes, newspapers, scribbled Post-it notes stuck to the fridge – the kind of clutter that fills every house. I sighed. I’d had no actual plan for the day, but now I set to work, once more focusing on the ground floor.

I couldn’t face upstairs, the bedrooms on the first floor – Elizabeth’s, Steph’s – and my old room on the top floor. Not yet. As I worked, I didn’t want to think of Elizabeth, so I tried to remember Steph instead. In the hall, I paused to look up the stairs.

She’d been a girly girl. Not like me. Her dressing table with its big mirror had been her pride and joy, crammed with make-up and brushes, hair tongs and all the paraphernalia of beauty. I might have been younger than her but even when I was older I never knew what to do with all that stuff. I wanted to paint real pictures, not myself.

‘Caroline!’

A voice fired across my thoughts. A memory of her voice. Elizabeth. Sharp and cultured and authoritative. I was standing at the bottom of the stairs, dithering about going up. My hand was on the polished balustrade, and I could clearly remember that voice, calling me from the bottom of the stairs.

‘Come here!’

I’d been in my room, right at the top. Maybe seven or eight years old? I’d put my book back onto the bed and slid reluctantly from the covers.

‘Caroline!’

I was wearing only knickers and a vest as I stood at the top of the stairs, my short bare legs pale white against the shadows of the upper floor. Elizabeth was on the landing below, outside her bedroom door, silhouetted against a blaze of yellow sunshine. Steph was in her bedroom, opposite Elizabeth’s, sitting at her dressing table. She was applying eye shadow and the door was open so she could hear every word.

‘Come here, Caroline!’ Elizabeth again.

I descended the stairs until I was standing right in front of her, rubbing the sweat on the palms of my small hands against my thighs, as I always did when she called me to her.

‘Look at you. Can’t you even be bothered to get dressed?’ Elizabeth snorted.

She seemed so tall and elegant and I stood there not daring to look up.

The slap whipped against my face, throwing my head backwards. It brought tears to my eyes, the sting of it burning on my skin. Elizabeth bent down to look at me, her face within inches of my own. She spoke loud and slow, as if I was particularly dim.

‘Get … dressed …’ She turned away. ‘You disgust me, Caroline.’

My hand had reached out for the banister, my fingers too small to meet around the wood. I glanced up and Steph caught my eye. I could feel my cheek stinging. Elizabeth was still within earshot and Steph hadn’t said a word, her blue eyes watching me as I climbed the stairs again.

My stomach growled. I’d scarcely brought any provisions from London. I needed food, so I decided to check out the village shops. Perhaps it was also an excuse to get out. The car bumped along the lanes and I parked alongside the village green, sandwiched between an old Ford Escort and a gleaming black and silver motorbike.

Larkstone wasn’t exactly a thriving commercial centre. Eight miles north of Ashbourne, it was too off the beaten track to be particularly touristy, but it had a pub, a Co-op and a butcher’s. I wondered if I would recognise anyone, or more likely if anyone would recognise me. It had been ten years since I’d left for uni. As I walked along the street, I saw roads and terraced cottages juxtaposed by uneven pavements. An old-fashioned but familiar lamppost stood on the corner by the Co-op, black paint peeling from its length. Still lit, a flare of white highlighted the mist that floated around it. That lamp had obsessed me; I’d sketched it over and over again when I was at school. Even later, when I was at uni, I would draw it from memory; there was something about the shape of it, the repeated glass, the cracks in the panes, the state of decay. I dragged my eyes away from it. Villages had a way of holding onto the past in this part of Derbyshire.

I went to the butcher’s first. The shop had the dull metallic stench of animal flesh, the counter laid out with neat folds of fat sausages, blood pooling beneath the steaks, bacon piled high.

‘Hello!’ I said.

The assistant looked only a little younger than me.

‘Can I help you?’ she said, smiling.

‘Er …’ I stood there mulling over what to get. Even the bacon rinds were perfectly aligned to show the stamp printed on the skin.

‘I’m sorry,’ the assistant said, ‘but do I know you?’

I looked up. Perhaps she knew me from school but I didn’t know her. I struggled to picture faces from the playground.

‘Maybe,’ I replied. ‘I used to live here years ago. Up at Larkstone Farm when I was a kid.’ I didn’t know why but the words came reluctantly to my lips.

‘Oh.’ She fell quiet. Then, ‘I’ll be right back.’ And she disappeared through a door to the rear of the shop.

I lifted my head, annoyance prickling. A man appeared, a large stained apron covering the expanse of his belly. He was followed by the assistant and the two exchanged glances as they entered the room. Did they know me? They must have known Elizabeth. Had they seen me at the funeral? The other faces there had been a blur, my thoughts mostly concentrated on Elizabeth and Steph. The woman stepped back to allow the man to take over.

‘We’re closed,’ he said.

‘Oh?’

I was taken aback. It seemed unlikely that the butcher’s would be closed at this time of day, with the door open and inviting.

‘Phone order,’ the man said. ‘We’ve got a large phone order. You’ll have to come back later or go to the supermarket.’ He nodded towards over the road.

He was clearly lying. What on earth? I stood there, dumbfounded.

‘Um, sure.’

I left the shop and turned back to look through the window. The butcher and his assistant were talking. The woman lifted her head towards me and there was something about her expression. I felt a flush of embarrassment, like I’d been caught stealing. Anger swept over me. Closed, really? What was their problem?

I crossed the road to the Co-op. A small queue gathered at the desk. I lowered my head, flipping up my hood, still aware of the heat on my cheeks. So much for company, now I felt the need to hide. I picked up a basket and headed down the aisle; it didn’t take long to choose what I wanted. As a last thought, I grabbed a couple of tins of cat food and made for the till.

‘Hello, Sheila, two packets of your usual?’

The assistant was addressing a middle-aged woman in front of me. She turned to pluck two cigarette boxes from the shelf behind her.

‘Thanks, Em,’ said the customer. ‘And a book of stamps.’

‘First or second?’

‘Oh, second will do. Have you heard? We think we’ve found it.’

I wondered what it was.

‘Yes, Pete was in a minute ago. Crying shame.’ The assistant opened the till, fishing for the stamps.

‘The sheep must have got run over last night. Some idiot driving too fast.’

I winced. A sheep hitting a car would have been nasty, for both parties.

‘Pete’s really angry, he loves his animals.’ The woman opened her purse.

‘Where did he find it?’ The assistant seemed to have forgotten about payment. There was a shuffling of feet behind me.

‘Outside Elizabeth’s house.’

The hairs on the back of my neck pricked up.

‘Well I suppose that makes sense, he’s got the field opposite, hasn’t he?’

‘Yes.’ The woman sighed, clutching her purse. ‘But the body was hidden in the verge – took a while to find it. Not much left of it either – the foxes had already had a go. Pete’s gone to fetch the trailer to shift it and ask his brother to help. But he’s annoyed with himself. It must have escaped the night before. Normally Elizabeth would have spotted it and given him a call.’

‘Well, she couldn’t have done that no more,’ said the assistant. ‘Twenty-one pounds seventy, love. Isn’t the house still empty?’

There was the chink of money and a rattle as it was stashed away in the till.

‘Pete said there was a car outside first thing this morning. Reckon one of the daughters has finally turned up.’

‘Really? Which one? The flashy one or the nutcase?’

I felt my ears burn, humiliation flooding my body. I lowered my head, fingers pushed deep into my jacket pockets. What was wrong with these people?

‘Don’t know, the car’s a bit crap, Pete said. Perhaps it was that car which hit our sheep?’

I ground my teeth. What right had they to make that assumption?

‘Oh, well, tell that lovely husband of yours how sorry I am when you see him.’

‘Sure. Thank you. See you tomorrow.’

The woman lifted a hand and left. I presented my basket and waited patiently. The assistant ignored me as she scanned the items but threw me a look when she got to the tins of cat food. My eyes dropped and I paid the bill as quickly as I could.

Back in the car, I pulled over when I got to the bottom of the drive to the house. On the roadside, they’d said. I told myself I needed to see what I’d been accused of, but perhaps the truth was that I’d always been drawn to the macabre, the visual trickery of the surreal, an artist’s fascination for the biological structures behind our physical façade. My car eased onto the verge and I stepped out.

The wind had picked up, with a bitter edge, bending the trees on either side of the road, already twisted and contorted from years of exposure on the hill. My hood whipped down and my hair caught in my eyes. One of the poppers on my coat was broken and I had to grasp the folds of it over my chest to keep the flaps from bursting open.

There it was. The feet were visible through the long grass and a tangle of briers growing in the hedge. It was just about recognisable as a sheep. The head was intact, but the body had been badly damaged, not just by a car. Entrails splayed across its woolly coat and something had tugged and pulled at the flaps of skin. The eyes were wide open, bulging from the skull, and its tongue lolled uselessly between its teeth. I couldn’t help but think of my stepmother, how her body must have looked lying on the floor at the foot of the stairs. I tried to push the image from my mind, gazing at the animal. Judging by the state of it, that hadn’t happened today.

I thought – what if it had been me? Yesterday, as I’d arrived? I’d been tired those last few miles, not particularly alert. What if I’d hit the sheep myself? No, I didn’t believe that. I would have felt the impact. And there was that car behind me. The driver would have noticed too. Surely, he’d have reacted if either one of us had hit an animal that big.

I reached out with my foot, giving the carcass a nudge. A bevy of flies rose up from the body, flying in ever decreasing circles before settling down to their business again. I felt my stomach flip. It was disgusting. But a sheep was just a sheep, wasn’t it? Another animal bred for consumption, its death inevitable one way or another. Like all of us, I thought.

I looked around me. I saw the last few leaves hanging on the trees, great piles of damp and blackened vegetation heaped on the verge below. I saw the remains of a pheasant cleaved to the tarmac further down the road, berries that clung shrivelled and inedible, rejected even by the birds. Already I’d alienated my neighbours without doing anything wrong at all. The strange looks at the butcher’s, the assumption of my guilt over this sheep, made without a shred of proof, and the vague gossip about Elizabeth’s two daughters.

‘The flashy one or the nutcase,’ they’d said – I certainly wouldn’t describe myself as ‘flashy’.

I’d only just arrived, after an absence of ten years. Why would they say that about me? I felt a sense of helplessness. Already it was as if I’d never left. This was meant to be a fresh start, wasn’t it?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/sophie-draper/cuckoo-a-haunting-psychological-thriller-you-need-to-read-th/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Sophie Draper

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фольклор

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Spooky and absorbing. I was gripped from the first page! CASS GREENThere’s a stranger in your house…When her stepmother dies unexpectedly, Caro returns to her childhood home in Derbyshire. She hadn’t seen Elizabeth in years, but the remote farmhouse offers refuge from a bad relationship, and a chance to start again.But going through Elizabeth’s belongings unearths memories Caro would rather stay buried. In particular, the story her stepmother would tell her, about two little girls and the terrible thing they do.As heavy snow traps Caro in the village, where her neighbours stare and whisper, Caro is forced to question why Elizabeth hated her so much, and what she was hiding. But does she really want to uncover the truth?A haunting and twisty story about the lies we tell those closest to us, perfect for fans of Ruth Ware and Cass Green.Readers love CUCKOO: ‘Spooky and absorbing. I was gripped from the first page’ CASS GREEN ‘A remarkably, taut and chilling debut. I absolutely loved it. Brilliant writing. All the creepiness. A heart-stopping ending’ CLAIRE ALLAN‘Sophie Draper is a remarkable new voice, combining beautiful writing with a gothic creepiness and a level of suspense which will keep the reader gripped to the end’ STEPHEN BOOTH′A brilliant, sinister debut that creeps under your skin and keeps you hooked until the shocking ending′ ROZ WATKINS‘Wow! This is what a horror story is supposed to be! Super spooky and absolutely wonderful in all its gothic glory’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER‘The ending was amazing. Psychological fiction at its best. Five Stars’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘I never use the term «jaw-dropping» but it best describes the rest of this spectacular read!’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘Stands up there near to of the top of the pile with narratives like «The Woman in the Window» and of course «The Girl on the Train».’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER ‘The ending BLEW. ME. AWAY. I feel like I’m going to have a book hangover now. SO, SO GOOD’ NETGALLEY REVIEWER