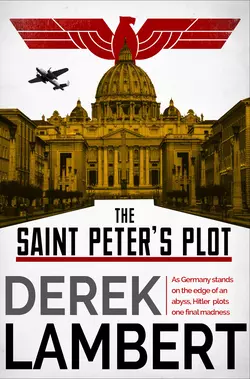

The Saint Peter’s Plot

Derek Lambert

A classic World War II novel from the bestselling thriller writer Derek Lambert.As the Russians and the Western Allies race towards Berlin, the Nazi hierarchy plots to escape the inevitable retribution facing them at the end of World War II.Kurt Wolff is a handsome, blond SS Captain and a member of Hitler’s personal elitist bodyguard. Yet he still has to know the greatest honour of all. He has been chosen to implement Grey Fox – The Saint Peter’s Plot – the most daring and secret mission of the War.As Germany stands on the edge of an abyss, the fate of this once great nation is in his hands.‘A fine thriller … very hard to put down’ Irish Press‘Mr Lambert is of the Wilbur Smith school of modern adventure writers – colourfully imaginative, totally convincing’ Manchester Evening News‘A thrilling novel … written with great sensitivity’ Derby Evening Telegraph

THE SAINT PETER’S PLOT

Derek Lambert

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_e704ae23-c4a4-5feb-a9ae-d0f63725f1c7)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Collins Crime Club

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by Arlington Books (Publishers) Ltd 1978

Copyright © Derek Lambert 1978

Design and illustration by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Derek Lambert asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780008268374

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2018 ISBN: 9780008268374

Version: 2018-03-14

DEDICATION (#ulink_94ad200d-d281-5956-85ca-2ea0ee01f29e)

For Mike and Sybil Keats,

Natasha, my god-daughter, and Alexia.

CONTENTS

Cover (#udf4e24d0-2944-506c-9428-3a99bb4458a0)

Title Page (#u7c67909e-fe94-58f2-a018-1fd94ceef0c6)

Copyright (#ulink_20caf1bf-541c-5e40-b7d7-03e8f373bccd)

Dedication (#ulink_2b210012-44c4-5fc3-87dc-0d2566738978)

Part I (#ulink_c54a18b5-ed2c-55b5-8211-0bf707da6389)

Chapter I (#ulink_99429198-0f75-5875-bd7f-8d782621ceb9)

Chapter II (#ulink_7b1ebcf8-6c31-5701-bc93-280d4b5bc6bc)

Chapter III (#ulink_d8dc168e-f5ca-5e21-a204-71318923fafb)

Chapter IV (#ulink_17b2b376-6141-5a10-806e-68c6d28269df)

Chapter V (#ulink_fd6c9776-5035-5bff-b21d-60c57d3cef34)

Chapter VI (#ulink_f4619641-58db-5412-b2c5-29c79b9c7bfc)

Chapter VII (#ulink_8c803c0c-f3cb-56df-b0aa-5ca0714dfac6)

Chapter VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXVI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXVII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXIX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXXI (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About The Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By The Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART I (#ulink_d720e5cc-e8a1-5744-972d-e2278f07f7ea)

I (#ulink_2c411046-b258-5dd7-8fa7-e8eac0de4d01)

The Commanding Officer of Adolf Hitler’s crack SS regiment took his leave of the Pope at 11.33 am on July 29th, 1943, unaware that he was closer to death than at any time during the bloody campaigns he had fought in Europe and Russia.

By 11.40 am Josef ‘Sepp’ Dietrich was walking briskly — a marching step almost — across St. Peter’s Square towards the line of white travertine stones that links the embracing arms of Bernini’s colonnade and marks the boundary of Vatican territory inside the city of Rome.

Behind Dietrich, former butcher and Munich bully-boy, a young man with the face of a saint and a 9 mm Walther pistol concealed beneath his jacket signalled to an older man stationed on the boundary line.

The older man, his bald patch as neat as a skull-cap, signalled back with the current edition of L’Osservatore Romano, The Vatican newspaper.

As Dietrich passed the Egyptian obelisk a sudden gust of wind disturbed the sultry day blowing plumes of spray from the two fountains, dislodging a prelate’s hat and startling a flock of pigeons into flight.

Dietrich, pugnaciously built, big-eared and cold-eyed, noticed none of this: he was too preoccupied with the speed of recent events. The Allied Invasion of Sicily; the withdrawal of his own regiment, Die Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, from the Russian front to Italy; the dismissal and arrest on July 25 of Benito Mussolini by his own people.

The next event, Dietrich brooded, would be the capitulation of Italy to the Allies. So? Germany would be better off without them!

By the time Dietrich reached the black Mercedes-Benz waiting for him near the boundary line, the man with the bald patch had climbed into the driving seat of a Fiat 500 fuelled earlier that morning with Black Market petrol.

Dietrich paused beside the Mercedes, drumming his fingers on the bonnet. Beside him stood a plain-clothes driver, rigidly to attention waiting to dive for the door-handle.

But perhaps a walk. It had been a long time since Dietrich, founder in the early ’30s of a unit of shock troops that were the forerunners of the SS, had walked for pleasure. You didn’t walk for pleasure in Russia; you didn’t do anything for pleasure in Russia — except kill Russians.

He turned to the driver. “I’m going to walk back.” The driver displayed no surprise. “Follow me at a discreet distance.”

Dietrich set off towards the Tiber, sweating inside the double-breasted grey suit that he had last worn at a meeting with Hitler at the Eagle’s Nest in the Bavarian mountains.

The suit hung loosely on him. Small wonder after the deprivations of Russia; the battle for Rostov — the Leibstandarte’s first defeat — the Arctic winter of ’42-’43, the Pyrrhic victory at Kharkov.

But in any case, Dietrich felt uneasy in civilian clothes. He was born for uniforms, swaggering uniforms with a silver death’s head badge on the cap, the double runic ‘S’ on a steel helmet, leather belts with My Honour is my Loyalty inscribed on the buckle.

But in Rome the Germans wore civilian clothes. They were not an occupying army. Not yet.

Dietrich observed with contempt the Italians walking the streets of their capital. In particular the men. They couldn’t wait to get out of uniform, and despite the shortages of war they still managed to groom themselves as beautifully as Berlin fairies.

When Dietrich reached the great rounded bulk of Castel Sant’ Angelo, once the military bastion of Rome, he toyed with the idea of recommending that all Italian deserters be thrown into its mediaeval dungeons. And the Jews, of course. As he crossed the Ponte S. Angelo, spanning the khaki-coloured waters of the Tiber, he smiled for the first time that morning.

Behind him, a hundred yards between them, two cars followed — the black Mercedes and the little Fiat. The man with the bald patch had now been joined in the passenger seat by the young man with the Walther. They were arguing.

* * *

The plan had been simple but conceived in haste.

Word had reached the partisans from The Vatican — next to Switzerland the biggest nest of spies in Europe — that Hitler’s most feared and fearless soldier, Sepp Dietrich, had been granted an audience with the Pope.

The core of the partisani was comprised of Italian officers and troops who had seen their fellow countrymen executed by the SS on the Russian front for lack of enthusiasm for what was, to them, an insane and suicidal campaign. Dietrich, the embodiment of SS fanaticism, was an irresistible target in Rome.

But the partisani, busy deploying themselves for the inevitable German occupation, were not yet organised. Dietrich might only stay in Rome for a few hours: the assassination plot had been devised in less than thirty minutes.

According to The Vatican source, Dietrich would, after his audience with the Pope, visit the Most Rev. Alois Hudal, the German bishop renowned for his Nazi sympathies, at his church, S. Maria dell’ Anima.

The site of the church was ideal for the assassination. A stolen German stick-grenade tossed as Dietrich climbed out of the Mercedes, a maze of escape routes through the old, cobbled streets.

The young man with the saintly features had served on the Russian front, and he had been posted outside The Vatican because he could immediately identify the SS Commander. He would signal to the older man who knew Rome as intimately as a cab driver. As soon as Dietrich took off in his Mercedes the older man would drive his Fiat through the short-cuts and tell the assassin to take up his position.

And it all might have gone smoothly enough if Sepp Dietrich hadn’t decided to take a walk in the sun.

In the Fiat the young man said: “We should kill him now.”

The older man gripped his arm. “Patience, my friend.”

“Patience!” Hysteria played tricks with his vocal chords. “The biggest bastard unhung strolls in front of us and you talk about patience!”

“He will go to the church. Then we will have him.”

“Supposing he doesn’t. Supposing he changes his mind. Supposing he decides to fill his guts with pasta instead of seeing a priest.”

The older man shrugged. He was a Sicilian, said to be a relative of the legendary Mafia leader, Don Vito Cascio Ferro, and his violence was controlled and reasoned. He wished it was he who had the Walther in the belt of his trousers.

He tried to reason with the younger man whose brain had been touched by the Russian winter. “If you tried to shoot him now there would be no escape. And in any case you might miss. What is the range of a Walther P. 38? The same as a Colt .45, forty-five metres, no more. And even as you pulled the gun he” — pointing at the driver of the Mercedes — “would kill you.”

And, thought the Sicilian, under torture you would blow everything.

The hand of the younger man strayed inside his jacket. “You didn’t see what he and his sort did in Russia. You didn’t see them beat men to death with the buckles of their belts.”

“The SS?” Unsolicited, a note of admiration crept into the Sicilian’s voice. “Ruthless, perhaps,” shrugging, “but certainly the best troops in the world. Possibly the best the world has ever known.”

The younger man stared at him. “You admire them?”

“I’m merely saying they’re good soldiers.’

The younger man tightened his grip on the butt of the Walther. “Are you sure you are fighting on the right side?”

“Oh yes,” said the Sicilian, “I’m sure of that. You see I’m a Sicilian,” as if that explained everything. “But it doesn’t prevent me from admiring an enemy. Even before I kill him,” he added.

They were across the Tiber now, turning left in the direction of the Piazza Navona. The Sicilian sensed that their private crisis was over: if the trigger-happy novice at his side had made a move he would have done it on the bridge.

The young man sulked. “You know something?”

“What?” braking when the Mercedes slowed down as Dietrich stopped to take off his jacket and drape it over one arm.

“I think you were scared back there.”

“Of course I was.”

“I could have killed him.”

“Of course you could,” the Sicilian said, taking one hand from the wheel and feeling the bald patch as though he wanted to doff it.

“I’ll tell the others about this,” said the young man and the Sicilian thought: “Not if I cut out your tongue, you won’t.”

Now Dietrich was crossing the road, gesturing to the driver of the Mercedes to stop.

“Now what?” said the younger man.

“Wait and see,” the Sicilian said.

As they passed the stationary Mercedes they saw Dietrich sit down at a white-painted table outside a trattoria. Immediately a waiter with a black bow-tie and a white apron was at his side.

“You see,” the young man said, “he’s going to stuff himself with pasta.”

I hope he doesn’t expect meat sauce,” the Sicilian said. “Times are hard.”

“What are we going to do?”

“What can we do but wait?”

The Sicilian parked the Fiat beside the flaking trunk of a plane tree. “I suggest,” he said to the younger man, “that you take a stroll. Two men waiting in a car are always suspicious. Believe me, I know.”

* * *

Dietrich didn’t order pasta. He didn’t seem to have the same stomach for food these days. He ordered a bottle of Peroni beer, put his feet on the chair opposite and tried to relax. But it was difficult. There was too much on his mind, not the least of which was his audience with the Pope.

Dietrich had determined not to be overawed. After all he had but one God — Hitler. And Hitler had responded to his worship to the extent of admonishing Heinrich Himmler Reichsführer of the SS: “Dietrich is master in his own house which, I would remind you, is mine.”

Dietrich had anticipated a measure of servility from the Pope. After all, The Holy See was in peril: the German 3rd Panzergrenadier Division lurked threateningly outside Rome and Hitler was reported to have stated: “I’ll go right into The Vatican. Do you think The Vatican embarrasses me?”

Certainly not. Nor would Pius XII embarrass Sepp Dietrich.

And yet when he entered the audience chamber and saw the Pope in his white and gold robe seated on a throne on a small platform, he had immediately felt intimidated. It was all stage management, he told himself. All the old tricks of assertion — the enforced wait outside the chamber, the dominant positioning of the throne, the lighting.

But it was more. Dietrich found himself not only in the presence of the Pontiff but of a consummate diplomat who, speaking fluent German — he had been Papal Nuncio in Germany for many years — committed himself with gentle authority to absolutely nothing.

But, Dietrich comforted himself as the cool beer coursed down his throat, I did make my point. Perhaps I didn’t extract a promise but my request was not denied.

He ordered another beer from the waiter who was probably a deserter or a conscientious objector. God, how he loathed Italians.

This time he gulped the beer. Attacked it in the way he satisfied all his appetites. But, when all the beer was gone, he finally acknowledged the root of his unease which he had been concealing from himself ever since he had left The Vatican: for the first time in his life he had admitted the possibility of ultimate defeat; for the first time in his life he had admitted the fallibility of the Führer. And to the leader of the Catholic Church!

Sepp Dietrich flung some money onto the table, swung his legs off the chair and strode across the road to the Mercedes.

To the driver he snapped: “Now take me to this other crow.”

* * *

The grey Fiat beat the Mercedes by thirty-eight seconds to the Vicolo della Pace where, at No. 20, visitors were admitted to S. Maria dell’ Anima.

The young man who had rejoined the Sicilian dashed into a doorway and spoke urgently to a partisan named Angelo Peruzzi, who was waiting with the German stick-grenade hidden in a worn leather brief-case.

Peruzzi nodded, gesturing impatiently to the young man to get out of the way, and slipped the leather tongue of the briefcase. He slid one hand into the briefcase and grasped the hollow wooden handle of the grenade. An observer might have assumed that he was fingering a Bible because he was dressed as that most inconspicuous of Roman inhabitants — a priest.

He walked swiftly up the cobbled side-street, arriving outside No. 20 just twenty seconds before the black Mercedes arrived.

And then the course of Italian history, of world history, might have been changed if it had not been for a beautiful Jewish girl named Maria Reubeni.

II (#ulink_e90d137b-d6ea-5dc0-8026-d442403deeeb)

Maria Reubeni had awoken that morning in her apartment in the old Jewish quarter of Rome near the Bridge of the Four Heads at 5.30.

These days she always awoke early, sometimes with problems of the previous night processed and solved, always with her mind turbulent with ideas.

Maria was a fervent Jew but not an Orthodox one. Her fervour was directed towards salvation rather than religious observation. She was sure that one day she would be a Zionist, but at the moment she was more concerned with saving Jews than rehabilitating them.

She rose from the bed and stood naked at the open window of her bedroom and peered round the yellow curtains for her daily glimpse of the river — the advertisement for the apartment had said simply ‘overlooking Tiber’ without mentioning that you could break your neck looking for it. She saw a swirl of water and withdrew from the window satisfied. It had become a ritual this daily peek at the river: not for any aesthetic reason: merely to remind her each day that the Tiber had once regularly flooded the ghetto into which Pope Paul IV had thrown the Jews in the sixteenth century. To Maria Reubeni the flow of the Tiber was the flow of Jewish persecution ever since.

But Maria was not a Jew who dolefully studied anti-Semite history while awaiting the next blow. She could not understand why the Jews of Europe were allowing themselves to be exterminated by the Germans. My God there were enough of them. Now she was determined to save the Jews of Rome.

She left the window open so that she could smell the first breaths of freshly-baked bread and coffee from the street below and turned on the shower in the bathroom. The cold water drumming on her shower-cap and sluicing down her body cooled her thoughts and gave them direction.

It was now a critical time for Italian Jewry. She and the other members of DELASEM, Delegazione Assistenza Emigranti (Jewish Emigrant Association), had known this ever since the war had started to go badly for the Axis powers. Italy would crumble. The Germans would move in. The Jews would suffer.

Now Mussolini had been ousted and it was just a matter of time … First DELASEM had to persuade the Allies and Italy’s new government under Pietro Badoglio to postpone an announcement of an armistice until they had got the Jews out of Italian-occupied France — and organised sanctuaries for the Roman Jews.

Maria dried herself, glanced briefly at her fine, heavy-breasted body in a wall mirror, dressed herself in a lime-green skirt and blouse and began to brush her long hair, so black that it seemed to have bluish lights in it.

Then she went to a cafe near the Theatre of Marcellus and ordered black coffee, the ersatz variety which tasted more like gravy, and a slice of pizza with a filling no thicker than a postage stamp.

The waiter with the anaemic moustache served her with a traditional flourish.

“Have you heard the news today?” he asked.

She shook her head, mouth full of pizza.

“Palermo has fallen,” the waiter told her.

“It fell on the twenty-second,” said Maria.

“Ah, you have better information than me.”

“I listen to the BBC.”

“Soon they will be on the mainland. Soon, perhaps, in Rome?” He looked at her hopefully. This goddess who had brains as well as beautiful bosoms.

“Perhaps,” said Maria.

The waiter pointed at the pizza and coffee. “Now every Italian knows we should never have gone to war. It is hurting us where it hurts most,” prodding his stomach. And then sadly: “We Italians are not fighters.”

She looked at him steadily. The waiter smiled uncertainly. She stood up, at least three inches taller than him. “Never let me hear you say that,” she said, searching for money in her handbag.

“You think we are fighters?” Astonished.

“You are implying that Italians are cowards,” Maria said. “Have you ever heard of Suda Bay?”

Miserably the waiter shook his head and began to clear the table to avoid her gaze.

“The Italians sank the British cruiser, York, and three supply ships. And how did they do it?” waiting until he was forced to look up. “With human torpedos, that’s how. And the pilots only ejected when the explosives were on target.”

“I didn’t mean —” the waiter began.

“The Italians are as brave as anyone. It is merely that we” — What am I, Jewish or Italian? — “are not stupid enough to sacrifice our way of life — that is what we have more than any other nation, a way of life — for an empty cause. But we are ruled by our hearts and not our minds, and that is why we allowed ourselves to be led to disaster by the Fascists.”

Her speech finished she strode from the cafe.

“Ah, she’s got guts, that one,” said a workman in blue dungarees sipping his coffee.

“Six months ago she would have been thrown into jail,” observed another.

“Perhaps she will be very soon,” said the first workman. “When the Germans come.”

The waiter said: “Why? The Germans have no love for Mussolini. Why should they throw her into jail for insulting him?’

“Because,” said the second workman, “she’s a Jew. That’s why, my friend.”

Outside the cafe Maria turned on her heel and headed towards the Corso. She was surprised at her pro-Italian outburst; after all, the Italians had introduced racial laws aimed at the Jews — even the Jewish artichoke had been renamed; but, Maria comforted herself, that had been the doing of the Fascists. But why had she wasted words on the waiter? Perhaps, she thought, because I know no man of character and strength in whom to confide; a man, that is, to whom I am physically attracted. Not even Angelo Peruzzi whose strength is a sham.

She didn’t take one of the green trams this morning. She wanted to smell the scents of Rome as it finally climbed from its bed after its drowsy awakening. The sky was misty blue and the streets rang with the clip-clop of horses’ hooves — more horses around these days than cars. But today Maria sensed a fresh nuance to the summer morning; a new expectancy as the Romans awaited the Germans, a razor-blade of cruelty; and when a pneumatic drill started up she jumped as though it were gunfire.

* * *

At the Fountain of Trevi Maria met by appointment a man she did admire. Although admiration was the limit of their relationship because the man was forty-eight — and a priest.

His name was Father Marie-Benoit, known in Rome as Maria Benedetto. He was a French Capuchin friar who had dedicated himself to rescuing Jews from their oppressors.

From the outset his career had been unorthodox. In the First World War he had served with the 44th Infantry Regiment as a stretcher-bearer and rifleman and had been awarded the Croix de Guerre with five citations and the Medaille Militaire. He was being trained as a machine-gunner when the Armistice was signed and was then transferred to the 15th Algerian Rifle Regiment in Morocco. After that he became Professor of Theology at the College International de St. Laurent.

At the outset of the present war he served first as an Italian interpreter with the French South-east Army Group. When France surrendered he went to Vichy, France, to Marseilles, sorting house of gangsters and refugees from German-occupied Europe. There he organised escape routes for the Jews.

Subsequently he was recalled by his Father Superior to Rome, where he had previously served, and was installed in the Capuchin Monastery at 159 Via Sicilia.

Currently he was working on plans to evacuate Jews from the area of southern France occupied by the Italians because, as soon as the Italian surrender to the Allies was announced, the Germans would move in and implement Hitler’s Final Solution.

Seeing him standing beside the fountain Maria Reubeni thought: “Now there’s a man.”

She walked up to him. “Good morning, Father.”

He smiled at her. “Good morning, my child.” His features were serene and yet it seemed to Maria that the serenity was a mask beneath which any extreme was possible.

He pointed at the fountain’s rocks set against the wall of the palace, at the statues of gods and goddesses and tritons, and the cascades of water spilling into the great bowl. “That water,” he said, “comes from Agrippa’s aqueduct, the Aqua Vergine, probably the sweetest water in all Rome. And do you know what the English used to do with it?”

She shook her head.

“Make tea.”

She laughed.

“Great people the English. A pity they never colonised Rome. If they had we might spend the rest of the day waiting for the sun to go down over the yard-arm instead —”

“Of waiting for the Germans to come.”

Father Benedetto sighed. “And come they will. Already the German Army is preparing to take over. We have a lot to do,” he said taking her arm. “Papers to forge, food to hide, escape hatches to oil.”

“But first,” she said, “the Jews in France, in Nice. How is it going, Father?”

“Slowly,” said the priest. “As you know, I’ve seen the Holy Father and sought his help. So far nothing’s happened but that was only thirteen days ago. These things take time. And the Holy Father is in a very difficult position,” he added.

“Very,” the girl said drily. “He finds it very difficult to acknowledge the existence of Jews. Particularly dead ones.”

“Now that,” said the Capuchin friar, “is not quite so. There are many factors involved. But this is no time for a debate about Papal diplomacy.” He led her from the little square in the direction of the Corso, gesturing with his free hand. “Palaces, basilicas, villas … We live in a museum. And there must be many dusty hiding places in a museum.”

“But will you be able to get the Jews out of France?” Maria asked.

“We hope to get in touch with London and Washington through the British and American representatives at The Holy See. The prisoners in The Vatican,” he said smiling. “Which reminds me,” tightening his grip on her arm, “I understand there was a very important visitor to The Holy See today.”

They reached the Corso, the windows of its elegant facades covered with dark-blue paper as an air-raid precaution. There were a few people around heading for the food queues; a kiosk opposite the Piazza Colunna displayed newspapers bearing nebulous headlines because editors were no longer sure what constituted good and bad news.

“Who was that?” Maria asked. “The Chief Rabbi?”

“On the contrary,” Father Benedetto said. “He was a German.”

“That doesn’t surprise me.”

“His name might.”

“Who was it, Hitler?”

“Not quite.” Benedetto bought a newspaper with a map of Sicily on the front page. The arrows on it seemed to indicate that the Enemy was winning. Or were they now the Allies? “His name is Dietrich.”

“Not Sepp Dietrich?”

“So it seems.”

“But what —”

“That is what we’d like to know,” the priest interrupted. “Why was Hitler’s favourite soldier-boy seeing the Holy Father?”

“Or why,” said the girl, “did the Pope grant an audience to a swine like that?”

“Whichever way you like to put it,” Father Benedetto said mildly. “Apparently it isn’t generally known that the audience took place.”

“How do you know?” She plunged her hands deep into the pockets of her skirt and began to walk slowly down the sidewalk, head bowed in thought.

“From our contact” — he corrected himself —” your contact in The Vatican. It seems,” tapping her on the shoulder with the rolled-up newspaper, “that you have a way with priests.”

“But why didn’t he contact me?”

“Apparently you were out of touch last night.”

“I suppose I was. I was having dinner with my father.” She took a pack of cigarettes from her handbag, then put it back because you didn’t smoke in the presence of a priest, certainly not walking in the street. “Who did he contact?”

“Angelo Peruzzi,” the priest told her and, because of her startled reaction, asked: “Why, does it matter?”

She said abruptly: “It might.”

“Well, you’d better go and see him,” said Father Benedetto uncertainly. “He’s a good man, isn’t he?”

“A good man, yes. But a weak man who disguises his weakness with bravado. If you’ll excuse me, Father, I’d better go to him now.”

“Very well, my child.” He touched her arm. “God be with you.”

Yes, she thought as she boarded a tram, Angelo was a good man. A brave man? Possibly. But bravery wasn’t necessarily strength, bravery didn’t embrace wisdom. How many acts of bravery had been committed for facile motives? Would Angelo kill just to prove himself to the rest of the partisani?

* * *

From the tram, jammed with rich and poor united by lack of gasoline, Maria gazed at churches and palaces opening their pores to the sun; at the sand-coloured walls of the Palazzo Venezia and its balcony from which Mussolini had declared war: at the white wedding cake across the square, the Vittorio Emanuele Monument.

In this square, when the overthrow of Mussolini had been announced, Maria had seen black-shirts flee for their lives as the crowd spat on a bronze bust of Mussolini. The euphoria had been sustained by the rumour that Hitler was dead.

Now the celebrants had retired and the Fascists were showing their noses again. Mussolini was still alive, the Germans would soon be here, and already in the streets you could see young men with bright blue eyes wearing combat clothes beneath civilian jackets.

Maria turned her attention to the stumps and roots of ancient Rome. The Allies had already bombed the city, wrecking the Basilica di San Lorenzo. How many more noble buildings would join the ruins of the Coliseum and the Forum before the war was finished? And who would destroy them — the Germans or the Allies? If only, Maria thought, the Italians could decide which was the enemy.

She alighted from the tram under a Fascist slogan, Many Enemies, Much Honour and made her way up the Via Cavour, a long and dreary street leading away from the sunlit ruins.

Here, in a small square reached by a flight of worn steps, Angelo Peruzzi had a one-roomed apartment. The tapestries of the square were underclothes and faded blouses hanging from the balconies. The only inhabitants at this time were starved cats that had escaped the stewpot.

Maria mounted the hollowed stairs and knocked on the door. No reply. She took the key to the room from her purse. Angelo had given her the key in the hope that she would join him in bed, but she had laughed at him and he had sulked for a week.

He was handsome enough with his brigand’s face and polished black hair; but he wasn’t a Jew, and in any case she had no respect for him.

The room smelled of stale tobacco smoke. On one side was an unmade camp bed. And he wanted me to share that! Opposite the bed a bookcase filled with innocuous volumes — these days you didn’t display either Fascist or Communist literature — and, on the walls, photographs of the Peruzzi family grouped round proud Papa who looked like an old-time Chicago barber.

Maria glanced at the papers lying on the table, one of its legs supported by a manual on firearms. She picked up an unlabelled bottle of red wine and smelled it. She grimaced. Gutrot! Angelo Peruzzi, aged twenty-eight, drank too much. It saddened her that she had to work with such men. But these days every willing hand was valuable, and Angelo was in contact with the most influential partisani, each group prepared to fight for its own rights in post-war Italy.

At first Maria had wondered why the more level-headed partisani bothered with Angelo. Then she had discovered that they used him because he liked to kill.

She was replacing the bottle when she noticed the sheaf of paper on which it had been resting. On the first sheet were scrawled three words in Angelo’s childish hand-writing: DIETRICH VATICAN HUDAL.

Slowly Maria lowered the bottle to the table. She glanced at her wrist-watch. It was 11.30 am. If Dietrich had been granted an audience with the Pope, then it would be over by now.

In two strides she was across the room, pulling back the bed, grimacing at the smell of unwashed sheets, pulling an old oak wedding chest from underneath. She tossed aside old magazines until she reached Angelo’s private armoury. A dismantled Thompson sub-machine gun, a Luger pistol and a stiletto with an elaborately carved handle.

All present and correct — except a German stick-grenade.

Maria ran out of the house into the square where the cats spat and arched their backs. Then she was in the Via Cavour running towards the centre of the city.

An old Lancia passed her, the driver — a fat man with a few strands of hair greased across his scalp — glanced at her over his shoulder. She waved and he smiled, winked and stopped the car.

“What’s the hurry, my pretty one?”

She jumped in beside him and told him to take her to the Piazza Navona as though she were addressing a taxi driver.

He shrugged, smiled, patted her knee and drove away.

“Urgent business?”

“Very.”

“Perhaps after this, ah, urgent business, we could meet and have a little drink. Perhaps in the sunshine on the Via Veneto …”

“Perhaps,” thinking: “If Angelo has ruined everything I’ll kill him.”

“What is the, ah, nature of this urgent business? It isn’t usual to see beautiful girls running on a hot day in Rome.” He glanced sideways at her. “You looked as though you were running for your life.”

“I’ll tell you about it later,” she said. “When we’re having that drink. And maybe after that …” managing a smile at the fat Fascist black-marketeer beside her. “Could we go a little quicker?”

“Nothing easier.” He stamped on the accelerator. “There’s no traffic on the roads. Not many of us are lucky enough to have cars these days. I have lots of beautiful things I could show you.”

As they neared the Piazza Navona Maria told him to stop.

“But I thought —”

“This will do,” she snapped.

As she climbed out she turned on him. “I know your face now, you fat pig. You’d better watch out.”

She lifted her skirts and ran through the narrow streets arriving at S. Maria dell’ Anima just as a black Mercedes was pulling up outside.

She saw Angelo Peruzzi in his clerical clothes as he was reaching into the leather briefcase. She threw herself at him, grabbing his hand inside the briefcase.

He swore and tried to push her away. She pressed her body against him, trapping the briefcase between them.

He pushed again with his free hand but she clung to him. He thrust his hand under her chin: “Get away from me or I’ll break your neck.”

She could feel his strength overcoming her; all she needed was a few moments more.

“Get away …”

Her head was bending backwards. Another fraction of an inch and the bones of her neck would snap. She gave way and fell to the ground, just as the door closed behind the bulky figure in the ill-fitting grey suit.

Angelo’s lips were trembling. With shaking hands he slipped home the tongue of the strap over the spring-clip on the case.

“You bitch,” he said.

III (#ulink_0a4f4381-de0c-546b-9bbb-d5f6ae429f7c)

The inquiry into the Dietrich episode was held in a cellar in the Borgo — a grenade’s throw from The Vatican, as Angelo Peruzzi had once put it.

But this evening Angelo Peruzzi was not in joking mood. He was trying desperately to maintain his prestige which is difficult when you have been all but overpowered by a woman.

Angelo’s prestige had been based on his willingness, and proven ability, to kill. And it owed its strength to the smallness of the group at a time when the partisani were an inchoate force of splinter groups which would only become a unified resistance movement when the Germans occupied Rome, and the British and Americans invaded the Italian mainland.

Angelo also drew his strength from Maria which had not been fully realised by the other members of the group. Until now.

The cellar was lit by a naked bulb hanging from the ceiling. The three men — the two who had stalked Dietrich, and Angelo Peruzzi — sat on packing cases sharing a bottle of grappa while Maria sat on the table swinging her long legs as her agitation increased.

Angelo’s only possible ally was the younger man with the frost-bitten brain, but he was no match for Maria’s passionate eloquence or the menacing presence of the Sicilian.

Angelo was saying: “I still think I should have killed him.”

Carlo, the younger man, said: “What kind of partisani are we if we fail to kill a big fish like Dietrich when he’s handed to us on a plate?” By now he was asking questions instead of making statements. He looked at the Sicilian who shrugged. “If you had seen men like that in Russia …” Carlo always produced Russia and they forgave him a lot because of what he had been through.

The Sicilian drank from the bottle of grappa and handed it to Angelo Peruzzi. “And what about the things the Russians did to the Germans? What about the story of the gold?”

“What gold?” Angelo asked, happy for any diversion.

“It seems the SS were searching for gold in some village. They threatened to arrest the entire population — and by arrest they meant murder — if the gold wasn’t produced. They left four men in charge. Next day they returned and in one of the buildings they found a box marked GOLD.” The Sicilian paused for effect. “When they opened it they found it contained the heads of the four men they had left behind.”

“Sometimes,” Carlo said, “I wonder whose side you’re on.”

The Sicilian gave a gold-toothed smile. “Mine,” he said.

“You should be in Sicily fighting the Germans.”

The Sicilian closed his smile, took a knife from his belt and tested its blade with his thumb. “My place is here in Rome. Here I have contacts. Family contacts,” he emphasised. “Sicily will fall within a month. And when the Germans march into Rome there will be much work to do,” throwing the knife at a photograph of Mussolini on the wall.

Maria lit a cigarette, blowing the smoke into the aureole of light around the naked bulb. “If Angelo had killed Dietrich we wouldn’t be in any position to fight the Germans.”

Angelo started to speak but she held up her hand.

“If Angelo had thrown that grenade the Germans would be here now. They would be in The Vatican. We would have been finished before we started. They would have slaughtered hundreds of innocent men, women and children. Our movement would have been obliterated.”

“Our movement?” The Sicilian retrieved the knife from the Duce’s face, already slitted with many wounds. “What exactly are your priorities?” His parents had sent him to Rome to be educated and he spoke Italian like a Roman.

She swung her heart-breaking legs a little quicker. “Very well, it’s obvious that I am concerned with the Jews. But that doesn’t mean we cannot work together.”

“That is true,” the Sicilian agreed. He held up the bottle to determine how much grappa Angelo Peruzzi had swallowed. “And I tell you now that I agree that it was a mistake to try and kill Dietrich.”

It was then that Maria realised the strength of the Sicilian. To be strong you had to admit your mistakes; beside the Sicilian, Carlo and Angelo were actors, cowboys.

The Sicilian said to Angelo: “But don’t despair, my friend. You did what you thought was right,” and Maria realised that the Sicilian was taking over. I would never have said such a thing to Angelo.

And to the three of them the Sicilian said: “We must stop fighting among ourselves. We must make decisions and keep to them.” Your decisions, Maria thought. “And if anyone doesn’t …” He spoke with his hands. “In Sicily we have always had a way of dealing with such people.” He threw the knife which this time embedded itself in Mussolini’s throat.

The two younger men remained sulkily silent.

“You see,” the Sicilian said to Maria, “I thought it was you who had ordered the killing of Dietrich.”

And now, she thought, he has all of us.

“You think I’m such a fool?”

He shook his head, smiling. “But you are a woman. A woman is ruled by her heart.”

Anger flared. She stubbed out the cigarette in a saucer. “I am not a Sicilian woman.”

“You are a beautiful woman.”

The anger expanded, although she was pleased by the blatant flattery.

“You’re out of date. Times have changed. This isn’t just a man’s war. Perhaps,” she said more calmly, “things have changed forever. Maybe the war has given us that.”

“Maybe,” the Sicilian said, emptying the last of the grappa down his throat.

“So what do we do now?” Carlo asked.

The Sicilian said: “We have to get guns. We have to meet the other partisani. We have to get organised. But first,” he said to Maria, “there is something you must do — find out why Dietrich is here.”

“Perhaps he’s looking for Mussolini,” Maria said tentatively.

“Possibly. But I doubt it. Otto Skorzeny’s been put in charge of that. And Hitler wouldn’t risk a clash of personalities like that — Skorzeny and Dietrich. Christ, what a couple!” the Sicilian exclaimed, admiration in his tone. “But in any case, they’re all wasting their time in Rome. Mussolini was taken to Gaeta and then to the Pontine Islands.”

“It’s not just Mussolini they’re after,” said Angelo. “They want to get Badoglio, his ministers, the King, every one of the shit-heads,” said Angelo, whose hatred embraced all authority-

“Even Skorzeny will have his work cut out,” the Sicilian said. “They’re all nicely tucked away, a lot of them at the Macao barracks surrounded by half the Italian army.”

“Perhaps Dietrich brought a message from Hitler,” Maria ventured.

The Sicilian brushed aside the suggestion. “The German ambassador to The Holy See could have delivered that. Any number of Germans could have delivered it. The Führer,” sarcastically, “could have telephoned The Vatican himself. “No,” he said thoughtfully, “there was something more to it than that. I think Dietrich was on personal business. SS business.”

He stood up, one hand feeling the bald patch. He was not a tall man, but his muscles pushed against his open-necked white shirt. The undiscerning would have likened his face to that of a peasant, but there was authority there — family authority — and small refinements in the set of his brown eyes, the sensitivity of the line from nose to mouth. None of which diminished the overall impression of implacable brutality.

He turned to María. “Now you must get to work. After all, you have the best spy in The Vatican.” He took her arm. “Come, I’ll see you home. By the way,” he said as they reached the foot of the stone steps, “did you know it’s Mussolini’s sixtieth birthday today?”

IV (#ulink_fe1427ed-eadd-5e40-a07e-f11374154d5a)

Maria Reubeni’s Vatican contact was praying. As usual his prayers were tortured.

Kneeling beside his bed in his Vatican quarters he pressed his hands together and shut his eyes as he had done when he prayed as a child in the Bronx.

“Please, God, forgive me for my devious ways.” Consorting with the Nazi bishop and at the same time betraying his confidences.

“And for doubting the Holy Father.” Wondering why, despite his financial help to the Jews, the Pope had not been more outspoken in his condemnation of their persecutors.

“And” — bowing his head lower — “for the times I have doubted Your infinite wisdom.” For permitting this terrible war irrespective of whether its victims found ultimate salvation.

Here he paused, because he was about to seek forgiveness for a carnal sin that he knew he would repeat since he was powerless to prevent it.

“And forgive me for failing to sublimate desires of the flesh.” Maria Reubeni.

Father Liam Doyle, twenty-five years old, grey-eyed with wavy brown hair and keen, Celtic features already stamped with the conflict of innocence and knowledge, prayed a little longer before rising and going to the window of his frugally-furnished room, and staring bleakly across the shaven lawns of The Vatican gardens where children played and fountains splashed in the dusk.

He had felt confused ever since his arrival at The Vatican two years ago from the small church in New York. There his principles and his volition had seemed inviolate: to help the poor — there were enough of them in the Bronx — and to guide the congregation, mostly Irish like himself, in the ways of God.

But Liam Doyle, son of a policeman and a seamstress, one of eight children, had been blessed, or cursed, by a facility with languages. First he had become fluent in Latin and then he had mopped up Spanish and Italian so that he was much in demand in the ghettos. Word of his linguistic abilities reached St. Patrick’s Cathedral and he was dispatched to Rome as a young seminarian.

The honour frightened him, but delighted those who worshipped in his grimy little church with its anti-Papal graffiti on the outside walls. “Patrick Doyle’s boy going to join the Vicar of Christ. Now there’s a thing.” Their delight was heightened by the fact that he would take with him the sins to which they had confessed — he was much preferred in the Confessional to the Bible-faced Father O’Riley — those sins, that is, that had escaped the wrath of Patrolman Patrick Doyle.

Liam Doyle’s fear had been well justified. He could not equate the splendid isolation of The Holy See with Christian charity. When he explored its treasure troves he remembered the pawn shop across the street from his old church where women hocked their wedding rings for a dollar.

Nor could he understand the arrogance of some of the monsignori in a world addled with poverty, starvation and suffering. Blessed are the meek …

And he never felt at ease in this state within a city. These blessed one hundred and nine or so neutral acres bounded by St. Peter’s Square, The Vatican walls and the walls of the Palace of The Holy See, constituted by the Lateran Treaty in 1929, where less than one thousand people lived tax-free lives of privilege.

Was this the way Jesus, the son of a humble carpenter, would have wished it?

But perhaps the fault lies in myself, Father Doyle brooded as the dusk thickened and settled on the courtyards, chapels and museum; on the grocery, pharmacy and radio station of the minute state from which the spiritual lives of three hundred and seventy-five million Catholics were ruled. There has to be authority and it has to be garbed with spendour: it is a throne. And there has to be immunity from outside pressures: a regal purity, perhaps.

Liam Doyle sighed. My trouble, he decided, as a plump cardinal strode past in the lamplight beneath like a galleon in full sail, is that I see every side of an argument. I lack decision.

He decided to brew a pot of tea on the gas-ring beneath a Crucifix on the wall. And while he waited for the kettle to boil he read the worn Bible that his mother had given him twenty years ago, seeking as always answers to his confusion. From the testaments he found solace, but it was only temporary, and when he awoke in the morning the doubts were still there, fortified by sleep.

The war had not helped Liam’s state of mind. It wasn’t merely the mindless slaughter vented on the world by an insane dictator: it was the effect of the war on The Vatican. It seethed with rumour. It was haunted with fear that the Germans would occupy it — they wouldn’t be the first to sack Holy Rome — and there was even a story that Hitler planned to kidnap the Pope.

But it was the politics of the place that particularly unsettled Liam. The uneasy suspicion-that the Papal diplomats were more concerned with stemming the tide of Communism than with condemning Nazi Germany. But how could you condemn a nation that was locked in battle with Bolshevism, the greatest threat to Christianity the world had ever known?

And there I go, Liam thought as he poured water into his dented aluminium teapot, seeing both sides of the argument again.

He poured himself a cup of tea and took a bourbon biscuit from a tin on top of the bookcase. Sitting on the edge of the bed, nibbling the biscuit and sipping the scalding tea, he tried to channel his thoughts in other directions — to his work for the Pontifìcia Commissione Assistenze (PCA), the Papal charity organisation for which he worked as an interpreter. But this time the Bible had failed him: his tortured train of thought continued its headlong progress.

Not only were Vatican officials engaged in dubious politics but many minor officials were involved in spying. They spied on the British and American representatives imprisoned in the Hospice Sant’ Marta, and on the Pope himself. Phones were tapped, cables deciphered, Vatican broadcasts monitored.

Many of the spies operated from ecclesiastical colleges and other Papal organisations outside The Vatican in the city of Rome. What disturbed Father Liam Doyle most acutely was that he was one of them. And that night he was going to meet the woman who had recruited him, Maria Reubeni.

* * *

Liam had met Maria through his work as an interpreter. He had lately mastered German and she worked as a Hebrew translator. In view of the plight of German Jewry it was inevitable that they should have met.

The meeting occurred in an open-air café beneath a green awning off the Via IV Novembre, near the ruined markets and forum of the Emperor Trajan, on June 2nd. The date was imprinted on Liam’s brain.

The purpose of the meeting was to question a Jewish refugee from Poland, who spoke Hebrew and Yiddish and a little German, in an effort to compile yet another dossier on Nazi atrocities, in order to provide The Vatican with the proof they continually demanded.

The refugee who had been smuggled across Europe to Marseilles and thence to Rome was so exhausted and scared that they had agreed on the telephone not to interrogate him in an office.

Instead of coffee or a glass of wine they gave him a lime-green water-ice. He was, after all, only twelve.

At first he spoke in small, shivering phrases but soon the warmth, the water-ice and the mellow antiquity of the place had their effect. And it was a familiar tale that he told the priest and the Jewess.

It dated back to November 23rd, 1939, when the Jews of Warsaw, where he lived, had been ordered to wear yellow stars. Then, eleven months later, confinement to the ghetto administered by a Jewish council. Famine, cold, deaths by the thousands.

Then in 1942, Endlosung, the Final Solution.

Fear halted the words of the little boy in the too-long shorts, shaven hair beginning to grow into a semblance of an American crew-cut. They bought him another water-ice, and waited. The girl pointed to a lizard, watched by a hungry cat, basking on a slab of ancient brick. The boy’s lips stopped trembling, he smiled.

And in a strange mixture of languages he delivered his adolescent version of the terrible facts that were leaking out from Eastern Europe. The beginning of the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, transportations to Treblinka death camp, gassings with carbon monoxide from diesel engines, followed by another gas (which Maria knew to be Zyklon B).

Horror froze around them in the sunshine.

Then the boy came to the revolt of the Warsaw Jews which began on April 18th, two months ago. He had been smuggled through the German lines in an empty water-cart during the fighting.

Maria leaned forward and spoke to him in Hebrew. The boy straightened his back and answered her firmly.

Liam asked Maria what she had said.

“I asked him if the Jews fought well.”

“And what did he say?”

“He said they fought like tigers.”

“And?”

She shrugged. “They were massacred.” She sipped her glass of wine. “But at least they fought. For the first time in nearly two thousand years they fought back as a people.”

Liam stared at her fascinated. When he had first seen her he had been aware of an instant physical reaction. But his emotions had been swamped by the sickening catalogue of inhumanity the child had carried with him across Europe.

Now the passion in her voice reawakened the feelings. He wanted to lean across the table and touch her hand. He was appalled.

She put away her notebook and said: “Well, there you are, Father, there’s your evidence. Do you believe it?”

“Of course I believe it.”

“But will anyone else inside your little haven believe it?”

He ran one finger under his clerical collar. “I cannot say,” lamely.

“So you, too, are a diplomat rather than a priest.”

He wanted to shout: “Not true.” To unburden his conscience to this beautiful, aggressive daughter of Rome.

She lit a cigarette. “Don’t worry, Father. They will want more proof as always. And they will say, ‘We need more than the word of a child.’ As if anything more was needed,” patting the boy’s stubbly hair. “Another ice-cream?”

At that moment the cat pounced. But the lizard was too quick for it, disappearing in a blur of olive movement.

The boy laughed and said to Maria: “That’s how I escaped.”

“No more ice-cream?”

He shook his head.

“Then it’s time I took you home.”

“Where is he staying?” Liam asked.

“He has family here. That’s why he was brought to Rome. They thought it would be safe here. But now …” Her hands finished the sentence, Italian style.

“A Polish Jew has a family in Rome?”

“You wouldn’t understand,” the girl said. “He is a Jew. He has family everywhere.”

Liam wondered at her hostility. He guessed — hoped — that it related only to her attitude towards The Vatican. She stood up suddenly, every movement vital, and paid the bill. Then she took the boy’s hand. “Good-bye, Father, it has been pleasant meeting you,” in a voice that belied her words.

Liam stood up and, to his amazement, heard himself proposing another meeting, lying to himself and to the girl, concocting a story that they needed to compare notes to enable them to present convincing evidence to the Papal authorities, knowing that this was a lie within a lie because many dossiers and petitions had been presented to The Vatican with negligible results.

She looked at him quizzically. “Very well. I’m dining in Trastevere tonight. Perhaps we could meet there for a drink. You do take a glass of wine, Father?”

“Occasionally,” Liam told her.

They arranged to meet at a trattoria, and he watched her walk away holding the boy’s hand and he knew that he should never see her again, that he should run after her and cancel the appointment, but he didn’t move. And, as she passed out of sight, he knew, standing there among the ruins of imperial Rome, that his life, his creed, had been irrevocably changed, that he was about to embark on a struggle with temptation which would be the greatest test of his life.

They met that evening in a trattoria, in the Piazza D’ Mercanti in the artists’ quarter of Trastevere on the opposite bank of the Tiber.

Liam was disappointed to find that Maria had company. A young man with swaggering manners and, Liam suspected, many complexes, and a Sicilian who was never called by his name. Both men indulged in the sort of banter which many men employ to disguise their unease in the presence of clergy.

They drank from a carafe of red wine and smoked a lot, as did most of the other customers who crossed the river to find Bohemia. A musician in a grease-spotted black suit and open-necked white shirt was playing a violin, but only the occasional thin note penetrated the noise of Italians relaxing.

Liam and Maria completed the farce of comparing notes, then the swaggering young man named Angelo ordered more wine and topped up Liam’s glass, and Liam thought: “You’re trying to get me drunk, my young friend. What better joke than a drunken priest?”

“So, Father,” the Sicilian said, lighting a thin cigar, “what do you think of the latest events?”

“The war you mean?”

“What else? Your information must be good, Father. The best in Rome, eh?”

“I doubt if I know more than you,” Liam said, believing he told the truth.

“Come, Father, an American priest inside The Vatican. You must have access to much intelligence.”

Liam frowned. He couldn’t think of any particular intelligence that had come his way.

“Are you not in contact with Mr. Tittman, the American diplomatic representative?”

“I’ve met him,” Liam said.

“I’m told that he is angry because he doesn’t always have the same privileges as other diplomats.”

“That,” said Liam, “is because in the past the United States had barely recognised The Vatican diplomatically. It is only through the Holy Father’s kindness that he is there at all.”

“And Sir D’Arcy Osborne, the British envoy. Do you know him?”

“I’ve spoken to him,” Liam said. He realised that the Sicilian was showing off his knowledge. “Why?”

“They’re both still sending their coded messages on The Vatican radio. A lot of good that will do them — the Italian Fascists have cracked the code and passed it on to the Germans.”

“You seem very well informed,” Liam said, wondering where it was all leading.

A girl wearing a low-cut bodice and ankle-strap shoes passed the table and tweeked his ear. He blushed.

Maria Reubeni lit a cigarette. She smoked too much, Liam thought, noticing and averting his eyes from the thrust of her breasts against her blouse.

She said abruptly: “Do you know Bishop Alois Hudal?”

“The German bishop?”

‘Nazi bishop,” Angelo Peruzzi interrupted.

The Sicilian prodded his cigar towards Peruzzi. “Let the priest speak.”

Liam told them he knew Hudal very well. He got the impression that they already knew this.

He had first met the diminutive, bespectacled bishop through his duties as interpreter. He had continued the association with the Austrian-born prelate for two reasons: to improve his German, and because Hudal seemed sympathetic to the Roman Jewry who might at any time suffer like the Jews all over Europe.

When he remarked on the bishop’s Jewish sentiments Angelo Peruzzi broke in. “You mean you believe all that shit?” stopping when Maria rounded on him and told him to clean his mouth out.

She turned to Liam. “I must apologise, Father, for Angelo. I will buy him a bar of soap on the Black Market.”

Liam smiled at her gratefully. But in the Bronx he had become accustomed to men who defiantly swore and blasphemed in the presence of a priest, especially when they had taken too much liquor.

The Sicilian examined the glowing tip of his thin cigar, somehow a sinister instrument in his thickly-furred hand. “What Angelo is saying,” as though Peruzzi spoke in a foreign tongue, “is that Hudal has expressed sympathy for the Jews for his own purposes.”

Laim looked puzzled.

Maria told him: “He means that Bishop Hudal doesn’t want the Germans to ship us to the death camps when they come. Not that he gives a damn — sorry, Father — not that he gives a jot about the Jews. But he thinks that such action would force The Vatican into denouncing the Nazis. If there was bad blood between Berlin and The Holy See it would destroy his precious dream.”

Liam wondered why they each interpreted for each other, perhaps the habit was catching. “What precious dream?” he asked, sipping the rough wine and grimacing.

The Sicilian said: “Hudal is a madman. He believes in a Holy Roman Empire. A partnership between the Nazis and the Church. A united front against Bolshevism.”

“He’s never mentioned it to me,” Liam said mildly.

“The bastard doesn’t know what side you’re on yet,” Angelo Peruzzi said, while the Sicilian pointed his thin cigar like a pistol and asked: “What side are you on, Father? And” — smiling his gold-toothed smile — “don’t say, ‘On God’s side’,” which was exactly what Liam had been about to reply.

Liam found the conversation bewildering. He thought the Sicilian looked like one of the debt-collectors who had called so regularly at premises near his church in the Bronx. Angelo looked like a homicidal psychopath. What was Maria Reubeni doing in such company?

“I am not on any side,” he said, glancing at Maria for support.

“Come now, Father,” the Sicilian urged him. “Even a man of the cloth must take sides. He must recognise evil.”

“But he needn’t participate.”

“But he always has,” the Sicilian observed. “At least in the history books I’ve read.”

Liam took another sip of wine. It didn’t taste quite so bad this time. “I cannot condone what the Germans have done,” he said after a while.

The violinist had moved up to their table and was playing Come Back to Sorrento. Liam would have liked to share the song with Maria, alone.

But the music hadn’t touched Maria’s heart. She asked: “Does The Vatican condone what the Germans have done, Father?”

Ah, the old, old controversy. He took another sip of wine, mustered his forces. “You mean the Holy Father?”

“That’s right,” Angelo Peruzzi said. “The Vicar of Christ, the boss.’

“Of course he doesn’t condone atrocities,” Liam told them. “His attitude is quite simple. He believes that if he denounced the persecution of the Jews they would suffer even more terribly.” Liam frowned, trying to put himself in the position of Eugenio Pacelli, the enigmatic Pope Pius XII. And probably” — no possibly — “he is right. In Holland the priests spoke out. The result? Seventy-nine per cent of all the Jews there — the highest proportion of any country — were deported to concentration camps. Furthermore,” Liam went on from his pulpit in the smokey trattoria, “he knows that Hitler is crazy enough to attack The Vatican if he spoke out against him. Destroy the fount of Christianity. Destroy the fount of humanitarianism. Perhaps destroy our civilisation …”

“I see,” said Maria as though she didn’t. “So Pacelli is really saving the Jews.”

“He is doing what he believes to be right,” Liam said.

“In other words he is doing nothing.”

“He is doing a lot,” Liam told her. “I know that from my work. Perhaps he is not saying a great deal …”

The Sicilian said: “Of course Pacelli was The Vatican’s man in Germany for a long time. He met the Nazi bishop there.”

Suddenly anger overcame Liam. “Are you suggesting there is some sort of conspiracy between Bishop Hudal and the Holy Father?”

Maria shook her head. “In fact we know that Papa Pacelli disapproves of Hudal.”

Liam smote the table. “I tell you that the Holy Father is doing what he believes to be right. I tell you that he has protested privately to Hitler. All he wants is peace.”

“And goodwill to all men including the Krauts,” said the Sicilian. He glanced at the heavy gold watch on his hairy wrist. “Time for us to go,” motioning to Angelo. “We’ll leave you together to discuss the fate of the Jews.”

“Aren’t you seeing me home?” Maria asked the Sicilian, and Liam heard himself saying: “Don’t worry, I’ll escort you,” like a college boy on his first date.

“Are you sure?”

“Quite sure.”

As the two men departed, Liam was overcome by a glow of pleasure untainted by physical desire. But for how long?

The torment of Father Liam Doyle was just beginning.

* * *

As Liam made his way to his assignation with Maria Reubeni on that July night six weeks later he noticed a group of tourists wandering past the columns of the Bernini colonnade. But they walked not as tourists, aimlessly and wonderingly; they walked stiffly with fists clenched and Liam, with his newly-found knowledge of intrigue, knew that they were Germans staking out The Vatican in case Benito Mussolini was hidden inside its walls.

Liam walked briskly over a bridge spanning the moonlit waters of the Tiber, absorbing the atmosphere of war-time Rome at night. Blacked-out windows, the ring of horses’ hooves on cobblestones and the tap of women’s high heels on the sidewalk. A woman smoking a cigarette approached him from a doorway on the opposite bank of the river, but withdrew smiling when she noticed his soutane.

As he walked Liam brooded about his relationship with Maria. For a while he had pretended that she merely wanted his help because, through the Papal charities, he could assist the Jews. And, deliciously and guiltily, he had considered the notion that perhaps she liked him for himself.

But soon logic asserted itself. The interest of the girl — and her unwholesome friends — was centred on his association with Bishop Hudal. They had known about the association from the beginning.

After their first meetings Maria had contented herself by asking apparently aimless questions. Then she had actively encouraged Liam’s friendship with Hudal “as you say he is so concerned about the Jews.”

When Liam was finally and hopelessly involved with her, she had made it clear that she wanted him to extract information from the German bishop. To spy.

But, being an intelligent girl, she had provided him with an escape route for his guilt: the information he provided was only being used in the interests of Roman Jewry if the Germans occupied Rome.

But Liam, now aware of the plotting within The Eternal City and The Vatican City, knew that far more was involved. He was being used by Maria’s friends, partisani, who were mustering their forces into an organised resistance movement. When the time came they would shoot, bomb, kill. Aided and abetted by Father Liam Doyle! Liam groaned aloud as he hurried towards his clandestine rendezvous with Maria. They met in a side street off the Largo Tassoni. The moonlight was in her hair and he could smell her perfume and he thought: “This is the last time,” but he knew it wasn’t.

“I’m glad you could come, Father,” she said.

Did she have any feeling for him at all? Or was he just a weakling to be exploited, a clerical courier to be used as she doubtless used other men.

“It is a fine night for a walk.”

“I have something important to ask you,” as they strolled beneath the stars.

“And what is that?” No longer my child.

“Sepp Dietrich visited the Pope yesterday.”

“Sepp Dietrich?”

She told him about the SS Commander.

“But why would a man like that seek an audience with the Pope?”

“That, Father, is what I would like you to find out.”

“From Bishop Hudal?”

“From the Nazi bishop,” she said, stopping and standing very close to him. “Will you do that For me?”

“I’ll try,” Liam said. And, hoping that she wouldn’t lie: “What has this to do with helping the Jews in Rome?”

Maria said: “The SS Special Action Units are responsible For massacring Jews. In Russia they’ve been killing 100,000 a month.”

But, from what she had told him, Liam had gathered that Dietrich was primarily a soldier. “You think he might organise a Special Action Unit in Rome?”

She nodded. “I do, Father.”

He knew she lied and it pained him.

V (#ulink_576e22b7-60df-5f58-a0b7-9aac73baf123)

But Liam Doyle was not destined to discover the reason for Sepp Dietrich’s visit to The Vatican from the German bishop, because the SS officer didn’t confide it to Hudal.

Dietrich distrusted priests. In particular eccentric priests trying to confuse pure National-Socialism with Christian doctrinaire.

But one day Hudal and the other pro-Nazi clergy with Vatican connections — men like SS officer George Elling, a priest, ostensibly studying the life of St. Francis of Assisi — would be vital links in the plan code-worded Grey Fox.

At the moment Dietrich wasn’t telling. His visit to S. Maria dell’ Anima was merely a preliminary move.

As he dismounted from the black Mercedes-Benz on the morning of the 29th July he vaguely noticed a priest and a girl struggling across the street and dismissed the scene as yet another example of Italian hysteria.

In the presbytery flanked by the tomb of the last non-Italian Pope, Hadrian VI, adorned with figures representing Justice, Prudence, Force and Temperance, he was greeted enthusiastically by the little prelate.

“It is indeed a pleasure to meet you,” Hudal said holding out his hand.

“The pleasure is mine,” Dietrich said without enthusiasm.

They went into a book-lined room where Dietrich noticed a painting of the Crucifix and photographs of Pius XII and Adolf Hitler on the walls.

On May 1st, 1933, Dietrich recalled, Hudal had entertained seven hundred guests, including top Nazis, on the premises and the place had rung with the cry: ‘German unity is my strength, my strength is German might.’

Hudal handed Dietrich a glass of wine. “And what brings you to the Holy City?” he asked.

“Pleasure,” Dietrich told him. He sat down on a threadbare easy-chair and crossed his stocky legs. “My unit has been transferred from the Russian Front. I’ve always liked Rome,” he lied.

He had visited the city once before. On May 2nd, 1938, in company with his beloved Führer, Von Ribbentrop, Josef Goebbels and the imbecile Rudolph Hess who had flown to Britain in 1941. He had detested the place then — its climate, its monuments, the instability of its people and its soldiery. Dietrich had even been forced to witness the Italian troops’ ludicrous imitation of the Nazi marching step known as the passo Romano.

“I am always pleased to receive a friend of the Führer,” Hudal said. He clasped his hands. “How are things on the Russian Front?”

“Not good,” Dietrich told him.

Hudal looked anxious. “But only temporary set-backs, I trust.”

Dietrich shrugged. It was only that morning that he himself had admitted the possibility of defeat. “We fought well in the Belgorod-Kursk sector.

Hudal leaned forward expectantly. “And?”

Dietrich said heavily: “General Model ordered a withdrawal. A strategic withdrawal, of course! The Ivans are marching on Orel at the moment.”

“But ultimate victory will be ours,” Hudal said, “It is God’s will. The Bolsheviks must be crushed. They are our principal enemies.”

“Our enemies? Do you mean enemies of the Church or enemies of Germany?”

The Vatican, Dietrich thought, was obsessed with the threat of Communism. From the Pope downwards. Thank God! He smiled thinly: it was an appropriate setting to mark his appreciation. And one of the leaders of the anti-Marxist movement was the fanatical little priest sitting opposite him.

Now Dietrich put the bishop to the test. “What if Germany were defeated?”

“Unthinkable,” Hudal snapped.

“But just supposing.”

“Then we would fight on.”

“We?”

“All of us loyal to the cause of National-Socialism. And Christianity,” he added as an afterthought. “After all, we rose from the ashes of the First World War.”

“The Americans and British wouldn’t let that happen again,” Dietrich said.

“They couldn’t stop us.”

“I think,” Dietrich said carefully, “that if we were to rise again it would have to be somewhere else.”

“You mean in Italy?”

The last place on God’s earth! “No, not Italy. The British and Americans would keep a tight rein on the Black Shirts here.”

Hudal looked at him suspiciously. “You seem very fatalistic, Gruppenführer.”

“Merely anticipating every eventuality.”

“Where then, Spain?”

“I hardly think so,” Dietrich said. “Franco has refused to cooperate with the Führer.” He paused, staring at the photograph of Hitler. “No, I think it would have to be farther away than that. Brazil maybe, one of the South American countries.”

“That seems rather far-fetched.”

But Hudal was out of touch. He hadn’t seen the slaughters in Russia. He didn’t seem to realise that the Allies would soon be on the mainland of Italy. That soon they would be landing in France. Above all he couldn’t comprehend the atmosphere in Berlin where already some of Hitler’s trusted lieutenants were planning their escape routes.

Patiently, Dietrich nosed his way through the little cleric’s dogma and blind fanaticism. “If — let us just say if — some of the top men wanted to escape when there was no longer any possibility of victory, would you help them?”

“If they weren’t escaping purely because of cowardice.”

Well put, Dietrich decided, regarding Hudal with new respect. “If they were escaping to form a new order elsewhere. The cream of Aryan manhood. To form an alliance between the Church and National-Socialism,” Dietrich suggested slyly.

Hudal’s eyes gleamed. “Then of course I would help.”

“And you have many followers here who would help?”

“Of course.”

“Inside The Vatican?”

“I have many friends inside The Vatican. The Teutonic College itself is on neutral territory.”

Dietrich stood up. He stuck out his hand. “Then let us hope we never have to make use of them.”

Hudal stood up. “Are things really as bad as you make out?”

“They’re not good,” Dietrich said.

* * *

That night as he lay between the soft sheets of a bed in the luxurious Excelsior Hotel where many German officers stayed, Dietrich, unaware that he had escaped death by a couple of seconds, reappraised his day. A bad one.

Soon he would be back fighting in Russia — the Führer couldn’t afford to keep the Leibstandarte “slummocking” (as Field-Marshall Günther von Kluge had put it) in Italy much longer — and today he had finally acknowledged to himself that only defeat lay ahead. So much for those shining dreams of the ’30’s, for the glorious victories of the Leibstandarte as they swept through Europe.

Dietrich, hands behind his head, staring at the ceiling, knew that he would fight to the last tank, the last man. And he would execute the Führer’s every order even if he had lost that intuitive touch of genius of the early days. Hitler had resurrected the pride of Germany: had shown its men that they still had balls. Elevated me from a nonentity to the commander of the most feared military machine in the world.

Dietrich reached for the suitcase beside his bed. Underneath a copy of Mein Kampf was a well-thumbed sheet of paper, a copy of Hitler’s remarks at the birthday celebrations for Hermann Göring on January 12th, 1942.

The role of Sepp Dietrich is unique. I have always given him the opportunity to intervene at sore spots. (Sore, well that was a bit of an understatement). He is a man who is simultaneously cunning, energetic and brutal. Under his swash-buckling appearance Dietrich is a serious, conscientious and scrupulous character. And what care he takes of his troops. He is a phenomenon … someone irreplaceable. For the German people Sepp Dietrich is a national institution. For me personally there is also the fact that he is one of my oldest companions in the struggle.

And I would die for him, Dietrich thought. Or, more practically, save him from the vengeance of the enemy.

Which was precisely what Dietrich proposed to do.

This was the plan known only to a handful of other top-ranking SS officers. To snatch Hitler from the muzzles of the enemy guns when Germany was finally on the brink of defeat. Regardless of the Führer’s wishes. Dietrich smiled fondly as he imagined Hitler’s ferocious reaction if he heard of Grey Fox.

And it was Grey Fox — Dietrich’s description of the Pontiff — that had prompted Dietrich to seek an audience with the Pope. How could Pius XII refuse with the 3rd Panzergrenadier camped on his doorstep?

Dietrich had proposed to sound out the Pope’s true feelings towards the Nazis. To test his reactions to any proposal to spirit top Nazis to freedom via The Holy See. To threaten, in the vaguest terms, retribution if he didn’t agree to collaborate. To extract a promise from the one man who couldn’t break his word.

But it hadn’t worked out like that. Dietrich had lost his motivation in the presence of the Pontiff with his long eloquent fingers, pallor of sanctity, aescetic features and gaze of total understanding.

The Pope had promised nothing, given no hint of his sympathies. He had handled the exchange with the practised ease of the career diplomat.

And finally Dietrich had kissed his ring a chastened man. Out-smarted by a priest!

But still, Dietrich comforted himself in his hotel room, the Pope had not denied any of his faltering proposals. Cold comfort.

Dietrich swore tersely and, thrusting aside the memory of the humiliating experience, took a green folder from the suitcase. On the first page was a list of eight names. The possible candidates to implement Grey Fox. Not Dietrich himself, nor the other SS conspirators, because they were all soldiers, nothing more, and they intended to fight to the last.

The chosen candidate had to have exceptional qualifications to carry out the most daunting mission of World War II. Bravery obviously — if he was Leibstandarte that went without saying. Authority. Resourcefulness. Unquestioning loyalty to the Führer.

But he had to have more even than these qualities. Much more. He had to be a man whose moral fibre had not been corrupted by the brutality of war. Untouched by cynicism. A man who still believed.

Inside the green folder were reports on the eight candidates. All good men. The finest examples of the Waffen-SS. But only one man had those additional qualities that Dietrich sought.