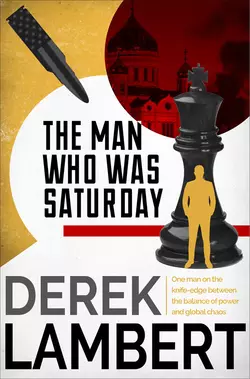

The Man Who Was Saturday

Derek Lambert

A classic Cold War spy story from the bestselling thriller writer Derek Lambert.Moscow treated defectors from the West with kid-gloves. That is, until they had outlived their usefulness. But the American Robert Calder was different. He had defected to Russia with information so explosive that even the iron-clad regime of the Kremlin shook with fear. It had kept him alive. Until now. For Calder is desperately keen to return to the West. So they place the ruthless and scheming Spandarian on his trail, a KGB chief with a mind as sharp as the cold steel of an ice pick. And as a back-up they unleash Tokarev, a professional assassin who kills for pleasure…‘Certainly puts Lambert up there with today’s top suspense writers’ Book Browsing‘Mr Lambert’s Moscow experience comes chillingly through’ Sunday Telegraph‘This terrific novel puts Lambert in a league with the best espionage writers of the day’ United Press International‘Another winner’ Pittsburgh Press‘Lambert is at the top of the class’ UPI‘Splendid stuff. Mr Lambert’s scenes have the clear reality of a Moscow winter, his people are three-dimensional and affecting and best of all he spins a fast story’ Baltimore Sun‘A white-knuckle number … Lambert produces straight-ahead, foot-to-the-floor excitement’ New York, New York‘Superior espionage fiction’ Waterbury Ct. Republican

The Man Who Was Saturday

DEREK LAMBERT

(with apologies to the memory of G.K. Chesterton whose man was Thursday)

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_417b9d71-ab38-5cbf-b3dc-2347e9158edb)

Collins Crime Club

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by Hamish Hamilton Ltd 1985

Copyright © Derek Lambert 1985

Design and illustration by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Derek Lambert asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780008268480

Ebook Edition © November 2017 ISBN: 9780008268473

Version: 2017-11-09

DEDICATION (#ulink_1a0245a9-904b-52fe-9cd5-4e850088130c)

To Roger and Lise.

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_bcab3143-154a-5171-aabf-3459d4dfb9e8)

‘… for life is a kind of Chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors or adversaries to contend with, and in which there is a vast variety of good and evil events that are, in some degree, the effect of prudence, or the want of it …’

Benjamin Franklin

CONTENTS

Cover (#u247f7b77-b378-5d6d-9fe1-f86c5f8d9cf8)

Title Page (#u51c0c855-d46e-5ecb-ae84-dd5c89a25fdd)

Copyright (#ulink_77dbfd4e-8ba4-5a0b-a2a5-b9a02cf859de)

Dedication (#ulink_1d1b0d31-a2b1-5ee9-9edd-8e2d9b86b553)

Epigraph (#ulink_f103fd8f-c12d-5f2d-ae67-b01639e0d521)

Opening (#ulink_a8073eec-a142-5643-826e-4bb37b84f7f5)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_a72fe751-1ccb-59af-9d6a-1804cf7d7e74)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_25063ef6-7c95-508f-b98f-03d53a0cce13)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_20a6e0ff-5489-5b92-8839-5a07522c8439)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_df8ce5b2-c091-5055-817a-b22003d691be)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_c6c85215-a4de-5d26-9336-fd528c6f8aaa)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_1357869a-dfeb-5cbd-9cc1-fda2de98d78d)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_920d2fd6-e90a-5094-8b55-5e8956e6e322)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_7114f12c-5314-56ad-ae8c-2d6ae3bf47f5)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Adjournment (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Middle Game (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Adjournment (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

End Game (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

OPENING (#ulink_b658d2cb-3348-5d77-a161-7fde35ac05b2)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_3dca1a72-c34e-5d90-9c65-387a1fa5c630)

Kreiber peered into the black wound in the river ice and in the light of a kerosene flare saw the face of a young man peering up at him.

He wasn’t surprised because nothing surprised him when he had been nipping steadily at the vodka bottle, but he was intrigued, so intrigued that he scarcely heeded the footsteps behind him.

Probably another fisherman who had left his hole carved in the frozen curve of the River Moscow to pick his way through the darkness to cadge some bait.

The footsteps slithered, stopped.

Kreiber continued to stare at the reflection of the young man whose face occasionally shivered into rippled particles in the iced wind blowing in from Siberia.

A face from the past.

My face.

Kreiber, packaged against the cold with felt and newspaper and a fur hat with spaniel ears, took a long pull of Ahotnichaya, hunter’s vodka, and smiled sadly, almost paternally, at the young warrior, armed to the teeth with ideals, that he had once been.

Twenty years ago a girl who had crossed the wall from East to West Berlin had espied those ideals and sunk sharp teeth into them. A refugee was what she had claimed to be; a recruitment officer seeking Western brains was what she had proved to be.

‘Look at the decadence around you,’ she had fumed to Kreiber, nuclear physicist, harnessing awesome powers to preserve peace. ‘Look at the capitalists, hedonists, wheeler-dealers and neo-Nazis. Do you think they give a pfennig for humanity?’

And so persuasive was her tongue, so compliant her magnificent body, that, reversing the trend, he had trotted from West to East of the divided city and thence to Moscow, losing the girl in transit, only to discover that in Russia there were those who didn’t give a kopek for humanity.

A long time ago. At forty-five he was now an old man in a still-alien city finding contemplative pleasure in long night-watches beside the black hole in the ice threaded with a line and tackle.

Taking another nip of firewater, he winked at the Kreiber he had once been. ‘Don’t worry,’ the wink said, ‘we’ll show them yet.’ He warmed mittened hands against his charcoal brazier and found strength from it.

The man in the long black coat stood directly behind Kreiber, eyes glittering in the holes in his grey wool mask.

A fish attracted by the kerosene flare tugged Kreiber’s line and the young face in the water disappeared in the commotion.

Kreiber pulled; the fish pulled. A fat lunch there judging by its strength, probably bigger than anything the other anglers hunched beside their flares and charcoal braziers had caught. Not that he would ever know: they didn’t discuss their catches with the foreigner who fished alone on the fringe of the ice-camp.

The fish gave a little. Kreiber slipped, kicking the brazier. A charcoal ember fell hissing on the ice. But his quarry was firmly hooked. Maria would cook the fish in butter and he would wash it down with a bottle of Georgian white.

An aircraft, red light winking, passed high over the fishermen engrossed beside their black troughs on the outskirts of Moscow. Kreiber wondered if it was flying to Berlin.

The man in the black coat pinioned Kreiber’s arms from behind, twisted one behind his back. He wasn’t excessively strong but Kreiber was vodka weak. Kreiber began a scream but it was cut out by a sweet-smelling rag pressed hard against his mouth.

He kicked backwards, lurched forward, pain burning his trapped arm. He let go of the line and thought ludicrously: ‘The one that got away.’

He was propelled, feet slipping, the last few centimetres to the edge of the neat round abyss that he had cut that evening. Beside him the line ran out as the fish dived.

A dreamy fatalism overtook him. The other anglers, he supposed, were too far away or too deep in their reveries to notice anything untoward. In any case you don’t tangle with a foreigner’s problems.

How about a last slug of Ahotnichaya to dispatch him glowing from this life? With his free hand he tore away the hand from his mouth but his plea for a last nip was a rubbery mumble.

Cold ran up his legs. His feet splashed. He was paddling in a lake in the Grunewald in West Berlin. Pressure on his shoulders, down, down.

He inhaled water as, with the girl at his side, he crossed the border from Capitalism to Communism never to return.

Bitch!

He began to fight, thrashing the black water with his legs, clawing at the terrible pressure above, but dragged inexorably down the ice-tube by water-logged newspaper and felt.

He managed to grasp the edge of the ice. Crack. He heard the bones in his fingers snap as heavy boots stamped on them. Crack. Still he held on, not feeling pain anymore, just the cold of the grave.

Boots, kicking, pushing, grinding. Broken fingers uncurled.

Why?

Then he gave up the fight.

Gently, almost gratefully, he slid into the darkness to join the young man he had seen in the light of the flare, realising in the end that he had been beckoning him.

Gazing at Kreiber’s alabaster features in the open coffin in the Institute for World Economy and International Affairs, Robert Calder was nudged by an elbow of fear. How accidental had the deaths of any defectors been? How natural the causes?

In front of him in the queue in the entrance hall Kreiber’s maid, Maria, built like a wrestler, sobbed enthusiastically. She moved on, sniffing into a scarlet handkerchief, Calder took her place directly above Kreiber’s shuttered stare.

According to the post mortem Kreiber’s blood had been lethally charged with alcohol. Another Friday night drunk. Another statistic.

Calder, legal brain blunted but still cynical, didn’t quite buy that. Kreiber’s capacity for hunter’s vodka had been phenomenal and he had been an experienced ice fisherman.

Bowing his head, Calder examined the face that had been spotted two days after his disappearance peering from beneath thin ice between reflections of the cupolas of the Kremlin close to Bolshoi Kammenyi Bridge. They had been ennobled by the mortician but beneath the cosmetics you could still trace wandering lines of indecision.

At least, another defector could trace them. Calder touched his own face. The lines, dye-stamped by doubt, were as indecisive as Kreiber’s. And yet according to the photographs, his features had once been strong, almost fierce, as he strode the campus, climbed Capitol Hill; even as he crossed the divide between Washington and Moscow.

Kreiber, you sad sonofabitch, what happened?

The elbow of fear sharpened.

He left the coffin and joined the group of mourners, mostly defectors who worked at the Institute, waiting to depart for the cremation. The coffin, marooned in the echoing lobby, seemed to be pointing at them.

A blade of cold reached him through a crack in the inner doors of the entrance. Outside, the chilled February breeze nosing through streets still winged with soiled snow would be an executioner – a winter funeral usually dispatched some of the bereaved to their own graves.

Maria was there, stuffing her mouth with sugar-coated red-currants which she fished from a cracked plastic shopping bag. And Fabre, the French defector, creased tortoise face bobbing above the moulting collar of his topcoat, and Langley, the Canadian, one time ice-hockey star and sexual athlete, and … a girl Calder didn’t recognise.

She had grey eyes and her black hair, released from the fur hat she carried in her hand, made an untidy frame for her winter-pale face. Langley, of course, was talking to her but he didn’t seem to be making much of an impression.

‘She’s the new girl in Personnel,’ Fabre informed Calder, lungs making rusty music as he spoke. ‘She keeps our files in order.’

So she was Surveillance. A pity. But you couldn’t blame her: she wouldn’t have any choice.

‘Attractive, ‘Fabre judged, ‘in a distant sort of way, ‘vowels in his English theatrically Gallic.

Distant? Perhaps. When cornered by Langley. But Calder detected a challenge in the set of her eyes and mouth. Her nose was, perhaps, a little too assertive but, having had his own broken in a locker-room brawl at Harvard, he was sensitive on the subject of noses.

Fabre, losing Calder’s attention, turned to Maria. ‘A merciful release,’ he said in cassette Russian, bobbing his head towards the coffin. Startled, Maria stopped chewing. Red juice trickled down her chins like blood. But Fabre didn’t give up that easily. ‘He died for a good cause.’

Maria turned her back on him: the only cause she knew anything about was earning enough money or horse-trading enough merchandise to keep the stew bubbling on the stove. Any other causes unsettled her: they sounded official.

Despite his misgivings, Calder smiled at her. She regarded him suspiciously for a moment, then grinned. It was spectacular, that grin, shining here and there with steel teeth, and it banished Calder’s foreboding. Maria delved into her bag and produced half a dozen white-powdered redcurrants cupped in one hand. She handed them to Calder who chewed them slowly; they were delicious, sweet and sharp. He glanced up and saw the girl from Personnel smiling at him; it was positively unseemly – any minute now they’d all be rolling in the aisles.

Fabre said coldly: ‘This is a funeral not a burlesque.’

Calder was saved by the doorman who, as the last of the mourners trailed past the coffin, herded by a KGB sheepdog in a square-shouldered topcoat, let the cold in. Whoosh, it entered snapping and Calder buttoned up his grey Crombie (Blooming-dales and still wearing well) as the girl put on her fur hat, tucking in her hair with long fingers.

He wondered how much, being in Personnel, she knew about him.

As the red-draped coffin, destined for Donskoi Monastery, was carried down the outside steps by six pall-bearers, their breath smoking with exertion, Maria dug him in the ribs. ‘Come.’ She licked red juice from her lips with the tip of her tongue.

But he didn’t follow her into the blue and white coach, doubling up as transport and hearse, along with the other forty or so mourners. Instead, although he had no intention of attending the last rites, he followed in his black Zhiguli.

He parked the small car in Donskaya Square and waited in it while the coffin and wreaths and red cushion bearing Kreiber’s three Soviet decorations were carried into the monastery, stone walls surrounding the five bunched domes of the cathedral still plastered with old snow. The corpse would be burned immediately, ashes flown to West Berlin in an earthenware casket adorned with a sprightly hammer and sickle. In the final reckoning both sides would be seen to be commendably decent. What harm could a few cinders do?

Through the exhaust fumes billowing past the windshield Calder picked out the defectors among the mourners following the coffin. American, British, German, French, Dutch, Canadian, Scandanavian, Australian … known to the KGB as The Twilight Brigade.

Twilight …. How many of them, trapped between day and night, between dog and wolf, had wondered, as he had done, about the deaths of their fellows?

Donald Maclean, British diplomat and partner in a celebrated defection in 1952, who had died in March ‘83, ostensibly from cancer. Could he have been slipped a few spoonfuls of Brompton Mixture, alcohol, cocaine and heroin? It was said to dispatch patients singing.

Be fair. Even if the mixture had been prescribed it could have been on compassionate grounds. After all it was prescribed in the West freely enough.

And Guy Burgess, Maclean’s partner in espionage and homosexual lush, who had died in his sleep in 1963 in an iron bed in the Botkin Hospital. He had died from booze. But, of course, the simplest way to hasten the death of an alcoholic is to inject him with alcohol.

When Maria and the girl – was she the reason he had driven to Donskaya Square? – had been hustled into the monastery by the shepherd from State Security, Calder drove onto Lenin Prospect and headed for the centre of the city. Tomorrow, he promised himself, such neurotic fantasies would be banished for ever. Unless another defector died too accidentally or too naturally or too soon.

If in doubt consult Dalby.

Calder arranged to meet him late that afternoon beside the waterless fountain at the entrance to Sokolinki Park. You could safely trade indiscretions in Sokolinki’s lonely pastures of snow and belts of silver birch thick with silence.

When Calder arrived on Friday night boozers were already gathering, tilting bottles of vodka bought legally or paid as wages or distilled by the friendly chemist on the corner of the block, banding together in case any of them collapsed, easy prey for teenage muggers.

Hands deep into the pockets of his Crombie, fur hat worn with a jauntiness he didn’t feel, Calder roamed between the burgeoning drunks and the pavilions remaining from international exhibitions. The cold crisped his nostrils.

No sign of Dalby. But, like the Russians with whom he mixed more compatibly than most defectors, he wasn’t noted for punctuality. From the very beginning of his banishment from Britain he had managed to adapt. Calder envied him.

‘Good evening my dear fellow.’

Calder spun round. Dalby still managed to surprise; that was thirty years of espionage for you. He was smiling benignly. Although the slanting lines on his face had settled into pouches Dalby, now in his seventies, still looked like an urbane pirate. He wore a peaked cap instead of a shapka, challenging the cold to take off his ears.

He squeezed Calder’s arm. ‘Come, let’s take a walk.’

They walked down one of the avenues that had once rung to the harness jingle of aristocratic coaches; on either side the snow had been packed hard and bright by children at play and cross-country skiers, but they had departed for the night and loneliness was settling.

Calder glanced at the fountain. He saw a figure detach itself from the boozers and strike out towards the avenue.

‘Is he there?’ Dalby asked.

‘I didn’t know you had a watchdog.’

Dalby chuckled. ‘Not me, my dear chap. You.’

Sokolinki was derived from the Russian for falcon because falconry had once been practised in the park and Calder felt the scissored nip of sharp talons. ‘I wasn’t aware I was being followed.’

‘You wouldn’t be, would you? Not if your watchdog is a pro. And the comrades are very professional in these m …matters.’ Paradoxically, Dalby’s occasional stammer refurbished his authority.

‘How did you know I was being followed?’

‘Let’s just say I’ve acquired a certain prescience over the years.’

No one quite knew what those years had entailed. But as he had been in the top echelon of British Intelligence it was safe to assume that he had blown great holes through many Western spy networks.

But he doesn’t know what I know. The knowledge gave Calder an edge over the enigma that was Austen Dalby; it also scared him. He was about to look over his shoulder again when Dalby, gripping his arm, said: ‘Don’t.’

‘Why would they want to follow me?’

‘You would know b … better than me. After all, you’re from another generation of … let us say idealists. Perhaps you know secrets to which I couldn’t possibly have had access.’

Did he – could he – know?

Calder directed the conversation into safer waters. ‘Idealists? A cosy euphemism.’

‘Then how would you describe us? Traitors?’

‘There isn’t a tag,’ Calder said. ‘We merely followed our convictions. We had our own sets of values but they weren’t necessarily idealistic.’

‘Values … you make Moscow sound very different from London or New York. Is it so different?’

‘It’s different all right,’ Calder said. He half-turned his head with exaggerated nonchalance. The crow-like figure was alone on the avenue. Perhaps he was just a lone walker – parks could be the most desolate places in the world.

‘Mmmmm. Outwardly, perhaps, but what about the equation?’

Always the equation. Vodka in the Soviet Union versus drugs in the West. Scarcities versus surfeits. Spartan flats versus chic apartments. Full employment versus unemployment ….

Dalby who, like most defectors, tilted the equation in Moscow’s favour, said: ‘Here a police state, in the West freedom. Such freedom. A g …gutter press that incites violence, encourages promiscuity. A political system hellbent on self-destruction. I sometimes wonder which is the CIA’s greatest enemy, the KGB or Congress.’

When they reached the birch trees and the silence made conspirators out of them Dalby said: ‘All right, out with it. Kreiber?’

‘He looked so … puzzled. Even in death he seemed to be saying, “Now what the hell was that about?”’

‘I should imagine everyone thinks that before they meet their maker, defectors, priests, gangsters.’

‘I doubt whether they ask themselves if they’ve wasted their lives by taking a wrong turning when they were too young to understand.’

‘Don’t they? I wouldn’t be too sure about that.’ Ice-sheathed twigs slithered together like busy knitting-needles. ‘But that isn’t what you really want to talk about, is it?’

Calder said abruptly: ‘Do you figure it was an accident?’

‘Kreiber? Why not? He had enough alcohol in his blood to fuel an Ilyushin from Moscow to Berlin.’

‘He’d been fishing from that hole in the ice all winter. He wasn’t likely to fall in.’

‘People can die falling over their own doorsteps.’

‘There was blood on the rim of the hole.’

‘Sharp stuff ice, especially in minus twenty degrees.’

‘And bruising on one arm.’

‘You don’t fall down a well without touching the sides.’

‘It must be wonderful to be so sure of everything.’

‘Why doubt? We’re here. There’s not a damn thing any of us can do about it. Let’s enjoy our elected way of life.’ Dalby tore a strip of paper bark from a thin tree and began to shred it.

‘And Maclean?’

‘Cancer, surely. ‘Dalby threw tatters of bark into the air. ‘Ah, you mean euthanasia. A possibility,’ he admitted. ‘Compassionate people, the Russians. Just listen to their choirs.’

‘And Blunt?’

‘Poor old Anthony? He hadn’t even defected.’

‘He was blown,’ Calder pointed out. ‘And he died within three weeks of Maclean.’

The American newspapers, part of the material analysed by Calder and his staff at the Institute, had given a lot of prominence to Blunt’s death. Queen’s art adviser and Establishment figurehead, he had been exposed in 1979 as a one-time Soviet agent and died four years later.

‘Aren’t we being a little m … melodramatic? Paranoic even? Blunt died from a heart attack.’

‘They can be faked.’

‘True.’ Dalby knew about such things. ‘An injection of potassium chloride, usually into the main vein in the penis where it isn’t readily detectable. It alters the ionic balance between potassium and sodium and the heart febrillates. If the body isn’t found for five or six hours the potassium chloride isn’t detectable. But who would want to kill poor old Anthony? He wasn’t of any use to anyone any more.’

Somewhere a twig cracked.

‘I guess I’m getting morbid,’ Calder said.

‘Positively funereal. Anthony wasn’t neurotic. He would have been tickled pink to think that he was buried on Spy Wednesday – the Wednesday before Good Friday when Judas asked how much he would be paid to betray Jesus.’

‘Okay, I’m stupid.’

‘Not stupid, you just listen too much to Institute gossip.’

‘You’re right, let’s get out of here. I’m purged.’

As they emerged from the wood the figure on the avenue turned abruptly and began whistling to an invisible dog.

When they reached the fountain Calder asked: ‘Why weren’t you at the funeral?’

‘I find my enjoyment elsewhere,’ Dalby replied. ‘I don’t read obituary columns either.’ Smiling, he pointed at a group of tipplers who had begun to sing The Sacred War – ‘Arise enormous country, Arise to fight till death’ – and said: ‘I was once asked by a fellow traveller from London with bum-fluff still on his cheeks why Russians drank so much. Do you know what I told him?’

Calder shook his head although he could have hazarded a guess – Dalby’s contempt for naïve Communists from the West who, like penguins, gulped every morsel of doctrine tossed to them, was well-known.

‘I told him, “Because they like to get drunk.”’

They shook hands, confessor and penitent. Behind them park and sky were a black-and-white print. And chords of sadness could be heard in the strutting voices of the vodka choir. Compassion? For whom? Themselves?

Briskly, Calder walked to his Zhiguli outside Sokolinki metro station. Kreiber, Maclean, Blunt … stupid! He put the car into gear and drove down Rusakorvskoe Road towards the Sadovaya, the highway ringing central Moscow.

The Estonian at the wheel of the battered cream Volga who had been keeping Calder under surveillance in the park gave him a five-second start before following.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_f82e4a58-72e9-5ed6-8eaf-09dcaaf031b5)

March 8th. Women’s Day in the Soviet Union.

From the ice wastes of the north to the deserts of the south, from mid-Europe across eight time zones to the Pacific, women reigned in the country comprising one sixth of the world’s land masses.

In fretwork villages becalmed in Siberia, in the splendid dachas of the privileged outside Moscow, men made love with unaccustomed tenderness, dressed the children, cooked dinner, washed the dishes and bought carnations at ten roubles a blossom.

Beaming, Mother Russia loosened her stays and relaxed. Until the following day when the men became goats again. Or so the feminists asserted.

On a platform in a wooden hall that smelled of resin and carbolic to the south-west of Moscow near the Olympic Village on Michurinsky Prospect, the girl from Personnel was poised to make just such an assertion. As it was her first speech, apprehension fluttered inside her like a trapped bird.

While the introductory speaker, mannish and indignant, barked hatred of all men, Katerina Ilyina nervously smoothed her blue woollen dress, fashionable but not provocative in case it upset the clucking hens in the audience.

Svetlana Rozonova, sitting on the chair beside her, patted her hand. ‘Don’t worry, you’ll slay them.’

Contemplating the forty women listening impassively to the speaker, Katerina thought that was extremely unlikely. If, like Svetlana, you were leggily tall with wild blonde hair and didn’t give a damn what people thought about you then, yes, you could slay them.

Katerina shifted on her rickety chair. It creaked so loudly that the speaker turned and glared. The trapped bird beat its wings with renewed agitation.

It was daunting enough making a first speech but when you knew that three women had already been expelled from the Soviet Union for promoting the same cause …. Like her they had been loyal to their country, like her all they had wanted to do was improve the lot of its women. Their expulsion had been wicked and it had sharpened the protest within her.

From her vantage point in the hall in which a stove was burning incandescently in one corner, Katerina surveyed her small band of rebellious womanhood. The turn-out was disappointing but what did you expect with an icy breeze still at large? Come the thaw and the women of Moscow would unfurl their banners of feminism.

The women were mostly young but there were one or two of the older generation among them padded with valenki boots and heavy coats, scarves folded on their laps.

Svetlana, wearing a wolfskin coat bought in Vladivostok by an Aeroflot pilot – when you were employed by Intourist as a courier you had such luck, not when you worked with foreign defectors – nudged her. ‘That one over there who looks like a maiden aunt. KGB – bet you five roubles.’

The maiden aunt, pepper-and-salt hair combed into a bun, was writing busily in a blue notebook. ‘No bet,’ Katerina whispered. Through a window she could see the fur hat and bulky shoulders of a militiaman. Ten policemen to control forty women. What did they expect, an armed uprising?

The speaker sat down. Katerina stood up. The bird’s wings beat inside her. ‘Good luck,’ from Svetlana. The faces had become a blur, stationary white moths.

When she opened her mouth the bird flew out. Her voice rang and words bore little resemblance to the ones she had rehearsed. She astonished herself. This Katerina Ilyina was a stranger. She crumbled her notes into a ball and dropped it on the floor.

‘Today is Women’s Day and today your man will be kind and charming. Perhaps he has already prepared the breakfast, bought you a carnation …. How very considerate of him. Perhaps even now he is making the beds, queuing at the gastronom ….’ She paused with the cunning of a seasoned orator. ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if he did just one of those things for the other 364 days of the year?’

Some women smiled at such an improbable vision. That was the trouble: too many women were indulgent; their plight was a radio and TV joke alongside absenteeism from work and graft.

Katerina hurried on. ‘They say we enjoy equality with men. They being men. All right, there is equality during the day when you and your husbands are both at work. But what about those long evenings after work. Is there equality then? Well, is there?’

A few heads shook.

‘While you scrub and sew and cook they enrich their minds in front of the television and refuel the inner man with firewater. What sort of equality is that? How can they talk about emancipation when fifty-one per cent of the work force are women? When eighty-three per cent of all doctors and health workers are women? When seventy-four per cent of all teachers are women?’

‘And what are you?’ a tough-looking woman wearing a red shawl demanded.

‘An adviser,’ Katerina retorted. My first heckler, she thought. ‘A seeker of women’s rights. Your rights,’ pointing at the woman. She felt quite capable of handling her. ‘Sad, isn’t it, that Soviet women are still cowed, yes cowed, by the fear of pregnancy. Not because you don’t want children,’ hastily, ‘because every woman wants children, but because you can’t afford them. Granted a mother is given twelve months off work after she’s had a baby. But if she wants to continue giving the child the care it needs she loses her job. And what does the State do about that? It provides facilities for abortion, that’s what. Only the other day I read about a woman in Kiev who had fifteen ….’

The woman with pepper-and-salt hair scribbled furiously.

The heckler in the red shawl shouted: ‘Tell her old man to buy some goloshes.’

A few women smirked at the reference to sheaths spurned by most men because the latex was so thick that it spoiled pleasure. For the first time Katerina faltered. Smut she hadn’t anticipated. Then she decided to invoke it. She was amazed at her adaptability.

She said resonantly: ‘In a truly liberated society there won’t be any place for remarks like that. Sex isn’t dirty, you know. Smut is merely a by-product of suppression.’

There, that should put paid to the potato-faced heckler. If she wasn’t interested in the movement why had she come? A paid trouble-maker?

Svetlana clapped her hands. ‘Hear, hear!’

Face screwed up with fury, the heckler rose to her feet and pointed a stubby finger at Svetlana. ‘I bet she’s fitted a few goloshes in her time.’

Svetlana had this effect on some women. Innocently she reminded them of girlhood dreams never fulfilled. Once she had worn a mini-skirt in the Arbat and women had leaped from doorways bunching their fists.

This time no one smiled and that might have been the end of it if Svetlana had allowed the heckler to get away with it; but that wasn’t Svetlana’s style. ‘What can she know about sex?’ she asked Katerina in a penetrating whisper. ‘Except on a very dark night.’

The heckler planted her hands on her hips. ‘Night,’ she proclaimed, ‘is for the modest, daytime for the shameless. There are some,’ glaring at Svetlana, ‘who don’t care whether they see the sun or the stars when they’re lying on their back.’

From the other side of the hall came a voice: ‘Sit down you with the face like a boot.’

Svetlana was rising to her feet but Katerina restrained her; sometimes she was wiser than her friend. What I need, she thought, is a rallying cry. She flattened her hands against her audience. ‘By arguing among ourselves we are playing into the hands of the male chauvinists.’

Chauvinistas pigs in the West. But Katerina didn’t feel that way about them: she liked men’s company. It was injustice that angered her.

The heckler, now under attack from her neighbours, finally sat down and Katerina moved triumphantly onto divorce – its alarming popularity – and the plight of the housewife with children abandoned by a husband for a rival down the assembly line.

She had intended to finish as she had started with an ironic reference to Women’s Day. Instead she heard herself saying: ‘The Revolution was supposed to have given women equality. It failed. Now another Revolution is under way. Women of the Soviet Union arise, you have nothing to lose but your chains!’

Desultory clapping. Well, there was surely nothing wrong with adapting Marx. Or was there? At that moment the militia moved in, three of them in long grey coats, from a door behind the platform.

Hands on the pistols at their hips, they stood beside the speakers menacing the audience.

Tossing her blonde hair, Svetlana said: ‘Hallo boys, and what can we do for you?’ while Katerina shouted: ‘Go on, shoot us.’

A fourth militiaman materialised, a tired-looking officer who needed a shave. He addressed the meeting. ‘Leave quietly by the door over there,’ pointing at the exit by the stove, ‘and you won’t come to any harm.’

Svetlana blew him a kiss.

Katerina, still raging, turned to the audience. ‘Take no notice of him: it’s Women’s Day.’

The officer nodded to a militiaman with a Tartar face and pock-marked skin. He clapped one hand over Katerina’s mouth and trapped her flailing arms with the other. Svetlana hit him on the head with her handbag before she, too, was pinioned.

More militiamen came onto the stage and Katerina thought: ‘This is monstrous, the way foreigners see us. ‘She bit one of the Tartar’s fingers. He swore but didn’t release his grip; oddly there was something gentle about his strength.

Two militiamen jumped from the stage, jackboots exploding puffs of dust on the floorboards. The women backed away knocking over chairs.

The officer shouted: ‘Take it easy, don’t panic. No action will be taken against you.’

Katerina continued to struggle but the Tartar’s arms were steel bands. The hand clamped to her mouth smelled of onions; perhaps he had been preparing a Women’s Day supper before being called out to put down a riotous assembly of female hooligans. Beside her Svetlana was vigorously kicking her captor, young with fat cheeks, with the heels of her magnificent boots.

The militiamen on the floor advanced steadily but placidly on the women. Regaining some of their dignity, they turned and made an orderly exit.

As the door opened the breeze brushed sparks from the glowing stove.

When the women had all gone – all, that was, except for the scribe with the pepper-and-salt hair – Katerina and Svetlana were released.

‘Well done, comrade,’ Svetlana said to the officer. ‘A great job, terrorising a handful of women. Guns against handbags. They’ll make you a Hero of the Soviet Union for this.’

The officer regarded her impassively.

While the Tartar sucked his bleeding finger, Katerina, fight gone out of her, said: ‘So what are the charges?’

They had several to choose from, the officer told her in his tired voice. Creating a breach of the peace, holding an assembly without permission, inciting violence. And how about hooligan behaviour for good measure? But he made no move to arrest them.

The exit door banged shut tossing dust and woodshavings against the stove.

The scribe mounted the platform and showed the officer a red ID card. He nodded and departed with his men.

‘After all, it is Women’s Day,’ she said, smiling at Katerina and Svetlana. ‘And now may I see your papers, please?’ She smelled of lavender water.

They showed her their blue work passbooks and internal passports containing their propiskas, their residential permits. The woman studied them cursorily, as though confirming what she already knew.

‘And now,’ Svetlana said, ‘may we examine your identification?’

‘If you wish.’ The woman dug in her handbag again. The red ID was militia, not KGB; that was something. ‘You know, my dear,’ she said to Katerina as she replaced the ID, ‘I agree with everything you say but not with the way you say it.’

Svetlana said: ‘What you mean is you don’t agree with freedom of speech.’

The woman tut-tutted. ‘Come now, let’s be realistic: this is the Soviet Union not outer space. We can’t allow public protest can we? That’s a phenomenon in the West.’

Svetlana buttoned up her wolfskin with exasperated precision. ‘Without protest we shall achieve nothing.’

‘But, my dear, a lot has been achieved without your assistance. You have no idea, when I was a girl ….’ Perhaps, Katerina thought, she had lost her man in the Great Patriotic War when twenty million souls had perished. ‘The point is that your goals must be achieved with subtlety. Nothing wrong with feminine wiles, is there?’

Katerina said: ‘Do you really believe that we are better off than we were?’

‘You must know that. Your life-style for instance. Clothes, entertainment, your relations with young men …. Why in my day we would have been shot for less.’

‘Then why,’ Katerina demanded, ‘can’t we speak our minds in public if we have such liberty? Why do the police have to be called in?’ She could still smell onions on her fingers.

‘I am merely advising you, nothing more. Just as an elder of your family might warn you.’ She smiled wistfully. ‘A maiden aunt?’ She touched Katerina’s arm. ‘I do hope you’ll take my advice, my dear.’ Apparently Svetlana was beyond redemption. ‘If not ….’

She didn’t finish the sentence. They all smelled smoke at the same time.

The fire was behind the stove. A tongue of flame snaked out from behind it, licked the stripped pine wall, fell back and returned to gain a hold. Resin crackled and spat.

The ‘maiden aunt’ took command. ‘Quick, the sand buckets.’

But the buckets were empty.

The flames leaped onto another wall. Smoke rolled towards the platform.

‘You,’ to Katerina, ‘call the fire brigade. You,’ to Svetlana, ‘get water from the rest-rooms.’ Grabbing a twig broom she jumped from the platform and advanced on the flames.

Katerina ran into the street. There, thank God, was a telephone kiosk. But when she reached it she discovered it had been vandalised. She ran around an apartment block, found another, dialled 01, fire emergency.

By the time she got back to the hall it was a bonfire. A crowd had collected and Svetlana and the ‘maiden aunt’ stood among them, snow melting at their feet. Sparks and ash spiralled into the grey sky. As the roof caved in the crowd sighed.

‘Happy Women’s Day,’ Svetlana said to Katerina.

‘So, what did you make of the maiden aunt?’ Katerina asked as they made their way to Vernadskogo metro station.

They had answered questions from a fresh detachment of militia, signed statements and finally been allowed to leave the smouldering wreckage.

Svetlana said: ‘She showed us the yellow card.’ Her pilot was a soccer fanatic, Moscow Torpedo. ‘Beware the red card next time. That means we’ll be sent off,’ she explained in case Katerina didn’t share her new wisdom. ‘Be warned, Kata.’

‘But why wasn’t she tougher with us? Why aren’t we locked up? After all we’ll be held responsible for burning the place down.’

Svetlana, hair escaping from her red and white woollen hat, glanced at her wristwatch and lengthened her stride, long thighs pushing at the wolfskin; she was hours late for a date with the pilot. ‘Odd, isn’t it? Let’s count our blessings.’

They passed a snow-patched playground in front of a new pink apartment block. Children were playing at war, Soviets against Germans. The Soviets were winning again.

‘What do you think will happen now?’ Katerina asked.

‘God knows. But take care, pussycat, take to your lair for a while.’

‘I can’t, it would deny everything the Movement stands for.’

‘Then get ready to spread the good word in a labour camp. Or outside the Soviet Union.’

Katerina thrust her hands into the pockets of her old grey coat, even shabbier than usual beside the wolfskin. ‘You forget things have changed since Tatyana Mamonova and the other two were expelled. There are letters about the plight of women every day in the newspapers.’

‘Whining letters, vetted letters. We’re inciting revolution. The Russians have had one of those and they don’t want another. If the Kremlin thinks we really pose a threat we’ll be hustled into exile and there won’t be a whisper about it in the media.’

‘But there would be in the West.’

‘So? Far less harmful than a forest-fire of protest in the Soviet Union.’

Katerina knew she was right and the knowledge saddened her. She was a patriot, didn’t they understand that? Of course they did, the final deterrent. The Motherland, don’t betray her. That’s why we put up with so much: it was something foreigners, confusing Country and Party, would never understand.

A man passed carrying a bunch of tulips, holding them like a baby to protect them from the breeze.

‘But,’ Katerina protested, ‘we’re doing this for Russia, for her women ….’

She remembered the old joke. Four men sitting in a bar nipping vodka. ‘Where are your women?’ asks a Western journalist. ‘The working classes aren’t allowed in here,’ replies one of the tipplers.

Things were changing, it was true. Five hundred of the toughest job categories had been designated Men Only and unmarried mothers were getting more money per child. But equality? It was light years away.

As they approached the metro station Katerina said anxiously to her friend: ‘But surely you aren’t thinking of quitting?’ It was unthinkable.

‘Why not? We won’t get anywhere.’

‘Not you!’

Svetlana turned and faced Katerina. ‘Well, not until they do something about those goloshes.’

Laughing, they slid five-kopek pieces into the slot in the turnstile and ran down the warm throat of the metro station.

Katerina had worked at the weekend updating the files on the defectors so she had a free day. In view of events that morning she thought it might be her last free day for a long time.

On the way home she broke her journey to pick up some Caspian caviar that Lev Koslov, her boss, had promised to supply for the party that evening.

Koslov was a past master at obtaining defitsitny goods. The only drawback was that he expected rewards – a pinch here, a fumble there. So far she had eluded his inquisitive fingers but a two-kilo tin of glistening black pearls, as rare these days as swallows in winter, that would take some evasion. At least he wouldn’t be able to come to the party: today being what it was he would have to dance attendance on his wife.

When she entered the tiny office she shared with Sonya Ivanovna the first thing she noticed on her desk was a vase of mimosa, a cloud of powdery yellow blossom that smelled of almonds. Koslov making his play! Under the vase was an envelope.

Katerina slit it with a paper-knife. The note inside said: ‘Enjoy your day.’ It was signed Robert Calder.

Katerina leaned back in her chair and stared at an avuncular Lenin on the wall. Since she had seen Calder at Kreiber’s funeral she had wondered about him.

Like the rest of her flock at the Institute he was a traitor and therefore contemptible. But Calder displayed qualities a cut above the rest of the turncoats. A sense of humour for one thing; she smiled as she remembered him stuffing the sugared redcurrants into his mouth, like a guilty schoolboy. And there was strength in his face that hadn’t quite gone out to grass.

Why had a man like Calder deserted his country?

It bothered her.

It also bothered her that she had come to work in this futile place. She had only been here for a month but already it depressed her. The legion of lost souls sifting foreign journals for insights into their country’s policies. Eyewash. The KGB grabbed shifts in policies before the policy-makers shifted them.

So why had she applied for the job? Come clean, Katerina Ilyina, blat, the influence that accompanies position. Bottom-of-the-scale blat, perhaps, but already she had a few perks – tip-offs about consignments of luxury goods in the stores, the promise of a one-roomed apartment of her own, the passbook that asserted she was someone to be reckoned with, a hint that one day she might be allowed to travel abroad.

With her gift for languages, English, French and German, she had romped through the academic interviews. What occasionally bothered her was the way she had weathered all the other interrogations. Why hadn’t her involvement with the feminist movement damned her? Could they possibly understand that her belief in the rights of women was not a contradiction of patriotism? She doubted it.

The knock on the door startled her. It was probably Sonya returning from one of her furtive perusals of Western magazines, eyes shining behind her spectacles at the discovery of some new and wonderful decadence. Presumably she had knocked in case Koslov was seeking his rewards.

Katerina called out: ‘Come in,’ and Calder walked in.

He seemed to fill the room.

He said: ‘I wanted to make sure you got the flowers.’

She touched the saffron blossoms. ‘I got them, thank you, they’re beautiful. But ….’ She had only spoken to Calder twice since the funeral.

‘I’m glad you like them.’

‘I love all flowers. Muscovites are like that – they see too few of them. Soon we’ll see snow flowers.’

‘Snow flowers?’

‘In the winter people fall and die from exposure. The snow covers them and they are lost until the thaw. When the snow melts they’re found perfectly preserved …. Is anything the matter Comrade Calder?’

‘No, nothing.’ Calder smoothed the frown from his forehead with his fingertips. ‘I think I prefer mimosa. I suppose it comes from Georgia.’

‘Probably. Somewhere in the south, anyway. Have you seen much of the Soviet Union, Comrade Calder?’

‘Don’t you know?’ His smile tightened.

She skated over that one. ‘Do you feel you’ve been accepted?’

‘People have been very kind.’

What sort of an answer was that?

‘Why don’t you come to a party this evening?’ she said.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_f7aee5ee-eef9-54b1-9b04-3298a47eb771)

Spandarian was a Georgian and therefore a schemer and on the afternoon of Women’s Day he was scheming busily in his office on 25th October Street.

On his desk were eight buff dossiers, dog-eared and stained from frequent perusals, and one eggshell blue folder, relatively unscathed.

Thoughtfully, stroking his luxuriant moustache and pulling on a yellow, tube-tipped cigarette, he picked up the dossiers in turn and scanned the latest computer print-outs inside them.

He didn’t touch the blue folder.

A knock on the door and his secretary, Yelena, cheeks as bright as a wooden doll’s, came in carrying a glass of lemon tea brewed in an electric samovar in the outer office. Spandarian slugged it with Armenian brandy.

He gestured out of the window at the grey sky drooping over Red Square. ‘A typical Moscow day.’ He sipped his fortified tea.

‘Spring is just around the corner,’ she said brightly. ‘March the eighteenth, Maslennitsa.’

Madame, he thought, you delude yourself. There was no way winter in Moscow would be locked away that early; in any case Maslennitsa was a country festival. But all Muscovites were the same: they couldn’t accept the slightest criticism of their capital city.

That was because they were Russians and still believed that the Russian republic was the Soviet Union. Didn’t they ever pause to consider the other fourteen republics? The hundred or so ethnic groups speaking different languages? Moldavians, Uzbeks, Armenians, Georgians …. Didn’t they ever cast their eyes to the sun-drenched south, peer down the Golden Road to Samarkand?

But soon they would have to face reality. Admittedly Russians accounted for more than half the 260 million or so inhabitants of the Soviet Union but the combined populations of the other republics were overhauling them, particularly with virile Georgians multiplying like rabbits. Then the Slavs in the Kremlin would have to tread warily.

‘You’re looking very smart today, ‘he told Yelena. He couldn’t quite muster ‘attractive’ even though it was Women’s Day. But he had bought her half a dozen pink carnations flown in from Tbilisi – at a knockdown price because he was Georgian.

‘Thank you, Comrade Spandarian,’ bright cheeks bunching. She was severely built and the rouge gave her a clownish air.

Spandarian finished his tea and dismissed her. ‘Adlobt.’ He spoke Georgian whenever he could. ‘That will be all.’

When she had gone he lit another yellow cigarette and stared through the window at the clustered cupolas and spires of the Kremlin. The Politburo was meeting there tomorrow; thirteen strong and not a Georgian among them. It was enough to make Stalin turn in his grave. Nine Russians, two Ukrainians – the Russians had to pay lip service to the fifty million restless souls in the south-west – and a couple of minority republics.

But with the appointment of Mikhail Gorbachev as Party Leader, the old order was changing. Out with the aged roosters, in with the young hawks. And who better placed to lead them one day than an up-and-coming Georgian KGB department chief?

Spandarian, head of the department responsible, within the Second Chief Directorate, for the defectors in Moscow, smiled crookedly at the gilded baubles across the square.

He closed his eyes and the baubles became a bunch of purple grapes freshly washed and glistening in a bowl in the restaurant at the top of the funicular climbing Holy Mountain in Tbilisi. He was eating lobio, beans in walnut sauce – his mouth watered – and drinking red Khvanchkara, the wine that Stalin, the most wily Georgian of them all, drank. Beneath him sprawled the city, cobblestone streets teeming with gangsters and girls with beckoning eyes, cafés filled with conspirators, perfumed air rustling with money and intrigue.

No, there was no one better equipped to scheme his way to the secretaryship of the Communist Party than a devious Georgian. Why in Tbilisi the name of Otari Lazishvili, Godfather of the ‘sixties who had swindled the State out of two million roubles and lived like a Rockefeller, was revered alongside Stalin’s. Recently the Kremlin had decided to purge the Georgian Mafia. Fat chance.

Spandarian saw himself as part Stalin, part Beria – Stalin’s police chief and executioner – part Lazishvili.

But a much more polished schemer than either Stalin or Beria. Stalin, God rest his soul, was only a cobbler’s son and when Beria wanted a woman he pulled her off the street! Spandarian, who was forty-two, belonged to an aero club and flew his own plane in Georgia, favoured sharp suits, had his wavy brown hair cut by a barber imported from Tbilisi, jogged and enjoyed modern music and read contraband Playboy magazines. The naïve sometimes asked him how he got away with it; the answer which he never supplied was simple – he had too much on his bosses and, for that matter, the granite-faced old men in the Kremlin.

Just the same he had to succeed at the job in hand. Fail, like a five-year plan, and you were doomed whatever clout you possessed. Spandarian opened his eyes and met the gaze of the ubiquitous V.I. Lenin regarding him shrewdly from the wall of his sumptuous office. Then he picked up the fattest file on the leather-topped desk, opened it and began to read the computer summary.

ROBERT EWART CALDER

Born April 5, 1946, Mt. Vernon, Boston.

Height: 1.8 metres.

Educated: New England prep and Harvard.

Profession: lawyer.

Specialisation: member of legal team advising Secretary of State.

Marital status: divorced.

Progeny: one son, Harry, by ex-wife, Ruth.

Recreations: baseball, sailing and chess!

Spandarian wondered if the computer had added the exclamation mark unprompted.

Character: determined but resolution undermined by adolescent ideals exacerbated by death of brother in Vietnam.

First approach: second year Harvard. At Elsie’s, Mt Auburn St. (A whorehouse, Spandarian had surmised at first. In fact an establishment selling king-size sandwiches to students).

Progress: finally suborned third year – Cross-Ref 8943XA, Infiltration US universities.

Grading: B but promoted when posted Washington.

Value: inestimable until blown.

Spandarian speed-read the rest of the summary. Reactions to Soviet life-style, sexual inclinations, companions, ideological stability, veracity of information brought from Washington ….

He paused, feeling the last sheet between his fingertips. What information? Value: inestimable …. What the hell did that mean? To his Georgian mind in which every highway was a maze, the lack of definition jarred.

Ever since he had taken over the department Calder had bothered him. The apartment on Gorky Street, the dacha, the air of impregnability that he carried with him like a briefcase full of secrets …. Spandarian suspected that Calder possessed knowledge that had been denied to him and that was insufferable.

Which was why he had mounted Grade 2 surveillance on the American. Grade 1 as from now, following Dalby’s report that he had expressed doubt about the manner of Kreiber’s death and was generally expressing disquiet.

And today Calder had made his own contribution to that surveillance. Mimosa indeed! Spandarian picked up the eggshell blue folder and peered into the life of Katerina Ilyina.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_0fc9842b-2341-5f4b-9ee4-82648d172f3f)

The Kremlin – kreml, fortress – is the hub of Moscow, more so than the seats of government of most capital cities. Driving into town there is no escape from it, the great avenues converging on it like the spokes of a wheel.

Around this fabled triangle of palaces, towers and cathedrals and around the old town of Kitay-Korad lie seven squares hemmed by a belt of green boulevards which are linked in the south, beneath the Kremlin’s walls, by the River Moscow. After the boulevards, and the next layer of assorted development – Czarist baronial, Stalinist wedding-cake, 1980s’ functional – comes the Sadovaya, the Ring, the city’s broadest highway, and finally a roaring motorway that girdles Greater Moscow as the Périphérique girdles Paris.

Katerina Ilyina lived on a spoke of the wheel, Leningradsky Prospect, leading to Sheremetievo Airport and, eventually, Finland.

When he crossed the Sadovaya, Calder pulled into a side road to consult the map Katerina had drawn. She would never make a cartographer: she even managed to make Leningradsky, as wide and straight as a runway, look like the trail of some demented insect. Past the Bolshevik sweet factory, she had said, not far from the Dynamo stadium.

He compared her effort with a printed map; it wasn’t much better. Cars swooped past on the avenue, phantom-quick in the moonlight. Across the street a dewlap of snow hung from an old wooden house, one of the few left in this area, old teeth among new dentures.

Why had she invited him to the Women’s Day party? There were a number of possibilities, most of them unwelcome; those that were welcome were unlikely.

Why had he sent her the mimosa? Easier. She was an injection of impetuous youth into the Institute, that fount of futile endeavour, and he wanted to share it. (The defectors reminded him of Dickensian clerks.)

Apartment block 33. There it was on the insect trail. He read the name of the side street under the dewlap of snow. Raskovoj. He was almost there.

The block was white and square with a children’s playground and thinning lawns scattered with a dandruff of snow. There were several notices telling tenants what they should not do.

Calder took the elevator to the fourth floor. Party sounds came from the end of a long corridor that smelled of disinfectant. No. 41, that was where the action was.

Katerina opened the door. She was wearing a black dress cut provocatively but not shamelessly low, Baltic, probably, or one of Zaitsev’s specials which never reached the stores. Her shoulder-length hair had been brushed until it shone blue-black. She wore an amber necklace, almost certainly Baltic, and her grey eyes challenged.

For one disturbing moment Calder saw himself through her eyes. Ageing – forty if he was a day. (He was thirty-eight). Tall and dark and defeated.

‘Comrade Calder, come in.’

He handed her a bottle of pink champagne and walked into Baccanalia.

Rugs had been drawn back from the parquet flooring of the sitting room, dark lacquered furniture pushed flush with the walls. Television, potted plants and assorted chinaware were on high ground out of harm’s way, a bed was doubling up as a couch. Guests crowded the small arena expansively.

‘Can I get you a drink?’

Her English was almost perfect. Although he spoke near-perfect Russian he answered her in English. ‘Are you sure you’ve got enough?’

The table at the end of the room was a distillery. A dozen different vodkas, Stolichnaya, Starka, Russkaya, Yubileinaya, lemon, pepper, hunter’s – Kreiber’s tipple, Calder remembered – caraway, the liquid gunpowder known as animal killer, and a few bottles of moonshine. The firewaters took pride of place. Among the other ranks were Georgian wines and Armenian brandies, Zhigulovsky beer, mineral waters, Limonad and the Soviet Coke, Sayani.

She smiled back at him, the smile at the funeral. ‘I think we can manage.’

‘Vodka then. Yubileinaya.’

‘You’re a connoisseur.’ She poured him a shot of vodka and a glass of mineral water and pointed at the zakuski. ‘You have to eat or the vodka burns holes in your stomach.’

Calder inspected the snacks. Glistening mounds of black, golden and red caviar, slices of smoked salmon, pickled mushrooms, gherkins, blinis, salamis and salads tossed with sour cream, brown and black bread.

He selected a couple of gherkins, tossed back the vodka, drank some mineral water and snapped his teeth into a gherkin.

‘You’ve done that before,’ she said.

‘Many times.’

‘We have a saying that drinking is the joy of Russia.’ She drank some white wine.

‘Then everyone must be very happy.’

‘It’s also a problem,’ she said. ‘Crime, absenteeism, divorce – drinking is usually the culprit. Even children in the kindergartens have been found drinking alcohol.’ She poured him another shot of vodka.

Calder noticed a stocky man, black hair needled with grey, pushing his way through the throng towards them. He skirted a poet tearfully reciting, stepped over two guests arm-wrestling on the floor and stopped beside Katerina. He carried himself like a soldier.

Katerina introduced him as her step-father. He clasped Calder’s hand and crushed it. ‘My name’s Alexander,’ he announced in Russian. ‘Sasha to you. My home is your home and now you must drink or else I shall be offended.’ He laughed hugely. ‘And now a toast. Silence!’ He waited until the only sound was the sobbing of the poet. Raising his glass he proposed a toast: ‘To Anglo-Soviet friendship and our guest from the United States.’

For a frozen moment everyone stared at Calder. He sensed no hostility in the concentrated gaze. But what was all this about? He had left America five years ago.

The stares dissolved, heads tilted. There was some scattered applause.

Sasha tapped his throat with one finger. ‘Pah, it is good to drink is it not, Gaspadeen Calder?’ He refilled their glasses with Yubileinaya. ‘Where do you live in America? I have only been to New York. With the choir, you understand.’

‘Sasha was in the Red Army Choir,’ Katerina explained and, turning her back to her step-father for a moment, whispered: ‘I didn’t tell them who you are.’

‘Boston,’ Calder said.

‘Ah. I pahked my cah in Hahvahd Yahd. How is that?’

‘Spoken like a true Bostonian,’ Calder said in Russian. The vodka was beginning to reach his socks. He smeared caviar on a finger of toast and ate it.

‘Sadly I had to return from New York before I could visit anywhere else. There was, ah, a little trouble ….’ Sasha winked theatrically. ‘But my voice stayed with me. Later I will sing to you.’

Katerina said: ‘The kitchen first. Have you forgotten what day it is?’

‘Ah, the most terrible day of the year. But if we don’t play their little game, Gaspadeen Calder, then we shall be denied our creature comforts for the other 364 days of the year.’ He winked again, with the other eye this time. ‘Isn’t that right, dochka?’ He pinched Katerina’s cheek and thrust his way back to the kitchen.

Katerina sighed. ‘Another male chauvinist.’

Beside them the arm-wrestlers, hands locked, veins bulging from their necks, grunted. In another corner a young man with long pale hair began to strum a guitar.

‘So I’m just visiting, huh?’

‘I couldn’t say you were a defector. My step-father wouldn’t have let you in. And not a single person in this room would have raised his glass to you.’

‘And you?’

Katerina sipped her wine. ‘You won’t find anyone in Russia who has much time for someone who ….’

‘Betrayed their country?’

She shrugged. ‘Deserted.’

‘Then why did you invite me here?’ He held up one hand. ‘Don’t tell me – you felt sorry for me.’

‘Because you worry me. You know, you left the West because you were disillusioned. That was the reason, wasn’t it? And now you seem to be disillusioned with the Soviet Union. I thought I’d show you what life here can be like.’

Calder gestured with his empty glass around the room. ‘Your friends certainly know how to enjoy themselves.’ It was the first time he had been inside a home like this; all the other invitations had been arranged – safe, tame, dull Communists. ‘It’s a bash.’

‘Would you find people enjoying themselves like this in Boston?’

Here we go, he thought, the equation. There was no escape from it. He said: ‘Sure you would.’ In his shared apartment near Fenway Park in his long-ago student days, for instance.

The arm of one of the wrestlers almost touched the floor, then sprang back again. The poet, to whom no one was listening, petulantly threw his glass against the wall.

A small woman with dimples and bright brown eyes said: ‘Is this the gentleman you were telling me about, Kata?’

Katerina introduced her mother.

Her mother said: ‘His glass is empty, Kata. Fill it with the demon. And don’t forget to eat, Gaspadeen Calder. We have a saying in the Soviet Union. Food on an empty stomach makes a full grave.’

Calder had long decided that Russians made up their sayings on the spur of the moment. ‘A wise proverb,’ he said graciously as she handed him cucumber salad and sour cream on a side-plate.

‘And what are you doing in Moscow, Gaspadeen Calder?’

Hurriedly, Katerina said: ‘He’s a writer. He’s writing an article for an American magazine.’

‘The National Geographic,’ Calder said, looking Katerina straight in the eye.

‘And how do you like our city?’ her mother asked. ‘Beautiful, no?’

‘Noble,’ Calder said. ‘Especially the Kremlin and the metro stations. They put ours to shame.’

Creases of pleasure appeared at the corners of her mouth. ‘We are very clean people, we Russians. Orderly and exuberant. Nothing by halves. And we look after our old people,’ she added.

Why don’t Intourist and Novosti introduce foreigners to people like this? Calder wondered. Instead visitors were forced to listen to actors reciting tired scripts, and taken to brochure showplaces instead of wooden villages clustered round a pump, to escape the dreaded condemnation: ‘Primitive.’

Not that the West managed much of a PR job: most Russians still thought London was a nineteenth-century stew.

Katerina’s mother said: ‘Soon we will eat and see what sort of a mess our men have made of it,’ sounding very indulgent towards male inefficiency. ‘And you, Kata, what have you been doing with yourself today?’

Calder sensed maternal worry: at the Institute it was common knowledge that Katerina was into Women’s Lib. What surprised everyone was that she was allowed to keep her job.

Katerina told her mother that she had been to a meeting. She didn’t elaborate and, although there was transparently more to it than that, her mother accepted the compromise and departed for the kitchen to see what sort of a hash the menfolk were making of supper.

‘What sort of meeting?’ Calder asked when she had gone.

‘You know perfectly well.’

‘The feminist movement?’ Calder frowned. ‘But why? I realise women get a pretty raw deal here. Divorce, abortion, exploitation …. But why do you care so much?’

She told him.

She was nineteen now, her father had left her mother when she was three. He met a girl at a summer camp on the Black Sea organised by the snow-plough factory where he worked and came home only to pick up his belongings.

The babushka, Katerina’s grandmother on her father’s side, left too and her mother had to quit her job as a waitress in the National Hotel to look after her daughter.

Her family helped financially and the State helped but she had to move into an apartment block of ‘boxes’ near the docks at Khimki Port. She got a job in a canteen there and paid a neighbour to look after Katerina during the day.

She tended to Katerina in the evenings and worked late into the night cooking and cleaning and mending.

A docker moved in briefly. He beat her up and stole her savings from under the mattress. Where else?

Her mother became bitter towards men. The bitterness was infectious.

Apart from visits from a family friend – ‘Yury Petrov, a pirate,’ Katerina said fondly – and an expedition to his home in Siberia this state of affairs lasted for thirteen years.

Then she met Sasha at the Central Soviet Army Drama Theatre on Kommuny Square and everything changed.

A miracle.

‘He sang his way into our hearts,’ Katerina told Calder. Her eyes were moist. ‘A wonderful man.’

‘But a chauvinist.’

‘Beyond redemption,’ she said happily.

‘Don’t you think the big-heartedness of Russian men outweighs their faults?’ They were both speaking English now.

‘You don’t understand: it’s injustice I’m fighting. I lived with it for thirteen years; it’s part of me. Just as it’s part of your Judy Goldsmith. When her father left home her mother lived for three years with five children in a chicken-coop. Now Judy Goldsmith is president of the National Organisation for Women, but I bet she still dreams she’s living in a chicken-coop.’

‘And you want to become president of something like that?’

‘Doubtful, after what happened today.’

‘The meeting?’

‘I burned down the hall,’ she said.

Sasha made his ceremonial entry from the kitchen carrying a dish of chicken cutlets and singing:

A circle for the sun

Sky all around

That’s what the little boy drew

Carefully sketched on his paper

Wrote underneath the corner.

Sasha paused. Children had materialised from another room. They stood like a choir poised for song. Sasha winked at them. Piping voices joined his baritone:

Let there always be sunshine

Let there always be blue skies

Let there always be Mummy

Let there always be me.

Then everyone fell on the food. Chicken and meat dumplings and beef stewed with sour cream and borsch. The men, Katerina’s mother admitted, hadn’t made such a hash of it.

‘So,’ Katerina said, spearing a meat dumpling with her fork, ‘do you feel as if you’ve been accepted?’

‘Marvellous people.’

‘That song – the chorus was written by a four-year-old boy. Sentimental people, the Russians.’

‘What would Sasha do now if I told him I was a defector?’

‘Throw you out on your ear.’

‘Has it ever occurred to you that it can take more courage to defect than to stay in your own country?’

‘You didn’t defect,’ she said, ‘you ran away,’ voice suddenly frosted.

The noise around him seemed to swell. Chink of cutlery against china, laughter, talk, the strummed notes of the guitar. The arm-wrestlers had called it a day, neither vanquished, the poet was asleep curled up like a bulky foetus. Sasha had his arm round the shoulders of Katerina’s mother.

He thought: ‘I’ll never belong.’

He heard her voice distantly. ‘… told you my story. Isn’t it time you told me what happened?’

He concentrated. ‘Not yet. Not here.’

‘Are you all right?’

‘I think I drank some animal killer by mistake.’

Would Sasha really throw him out? Of course. The Red Army Choir rang with patriotism. The Twilight Brigade took a different view. Their motto was Samuel Johnson’s: Patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel.

Calder felt like an island. He told Katerina that he was leaving.

‘So soon?’

‘Perhaps you’ll show me more of your Moscow. The city foreigners never see. I remember as a kid on the waterfront in Boston there were some slot machines. You fed them a nickel and a tableau came to life. A circus, a rodeo, that sort of thing. That’s the Russia foreigners see. Feed Intourists with hard currency and the tableaux come to life. But with you I have a passport ….’

‘You have Soviet citizenship, an internal passport. You’re free to travel.’

‘You know that’s not true.’

She gave a shrug, a dismissal. ‘Perhaps one day ….’

Calder said goodbye to Katerina’s parents. ‘But the party’s only just beginning,’ Sasha objected. He sung a few bars of the Volga Boatman. ‘The song all Americans know.’ Calder braced himself for Sasha’s handshake but it was limper this time, emasculated by firewater.

Calder left.

Outside the cold embraced him like an old friend and sent the vodka coursing through his veins. With a skull full of fancies he made his way on rubber knees to the Zhiguli in the parking lot.

The cream paint on the battered Volga that followed him shone silver in the moonlight.

When he got back to his apartment off Gorky Street Calder found Jessel from the American Embassy waiting for him.

Jessel, a New Yorker, was his link with the United States: he was one of Jessel’s links with the Soviet Union. Jessel worked for the Commercial Counsellor. He was middle-aged with amiable features and a soft voice and thin, ear-to-ear hair. He didn’t look at all like a spy and that was his strength.

He pretended to like Calder but from time to time Calder caught a frayed glance and he knew that Jessel was thinking: ‘How can you have done it?’

To make things easier for themselves they played chess.

For Calder chess was his therapy. It gave him direction. He believed it to be the distillation of human behaviour encompassing prodigious foresight, petty opportunism, grand strategems, puny deceptions and glittering combinations that could fail because of a single unsighted flaw. Moreover chess was the honed product of centuries of trial and error, a diamond made of compressed genius.

Jessel, who had the key to the apartment, was sitting in front of a crowded chess board drinking bourbon.

‘Make yourself at home,’ Calder said.

‘And where,’ Jessel asked, moving a white pawn, ‘have you been making yourself at home?’

‘At a party.’

‘Obviously. Whose?’

‘None of your business.’

‘That,’ Jessel said mildly, ‘is for me to decide.’

Calder took off his coat and shapka. In the kitchen he dropped ice-cubes into a glass and poured Narzan mineral water onto them. The ice-cubes cracked back at him. The vodka had made his tongue thick and unmanageable.

Glass in hand, he went back to the living room. Jessel had lit his pipe and rearranged the chess pieces in pre-battle order.

Calder gestured around the room with “his glass. ‘Clean?’

Jessel picked up the bag containing his electronic sweep. ‘As a whistle. The comrades must trust you. What were you drinking, paint-remover?’

Jessel wasn’t a great drinker. He took care of himself and jogged every morning along the banks of the Moscow River. He was tougher than his appearance suggested.

Calder said: ‘You know better than that: they don’t trust anyone.’

He moved to the window and gazed at the floodlit public gardens below. He enjoyed them. In summer they dozed dustily; in winter they radiated vitality as youngsters with polished faces skated exuberantly along paths hosed with water to convert them into canals of ice.

In fact he enjoyed the apartment near the monumental buildings of Gorky Street, the best bakery in town and the extravagances of Gastronom No. 1. Compared with the barrack-block flats occupied by most of the defectors it was a palace and attracted much envious comment. But then they didn’t know what he knew. He was a VID, a Very Important Defector, and as such was entitled to a home isolated from the Brigade. He even had a wooden dacha in the country. Dalby was the only other defector with one of those.

Jessel said: ‘You’d better take white. In your condition you need the extra move.’

‘I can still beat you blind-folded,’ Calder told him. In fact there wasn’t much to choose between the two of them, although Jessel was the more cautious player, Calder finding it difficult to resist a potentially swashbuckling brilliancy without assessing it thoroughly. Patience was what he lacked. Jessel’s careful intricacies had earned him the right to play in a few minor tournaments in the Soviet Union and to spy in unlikely places. ‘I’ll take black,’ Calder said.

P-K4.

P-K4.

Calder made his move standing beside the marble-topped coffee table and continued to patrol the living room; movement, he hoped, would help to sober him up. The apartment helped to settle him – he had grown into it and it was shabby like himself. Period Muscovite with sombre furnishings and a rich, balding carpet; but it did contain small glories such as carvings leafed with gold, a painting of Siberian pastures feathered with mauve blossom, a chandelier whose frozen tears had been washed with soapy water only that morning by Lidiya, his maid. Unlike so many members of the Twilight Brigade he hadn’t cluttered it with bric-à-brac, the detritus of the abandoned West.

‘Your move,’ Jessel said.

‘Knight to queen’s bishop three,’ Calder replied without looking at the board.

‘You’re very sure of yourself.’ Jessel undid his button-down collar and loosened his striped tie.

‘How many times have we played the Ruy Lopez before?’

‘I might surprise you this time.’

‘Surprise me,’ Calder said.

A few minutes consideration, then: ‘Your move again.’

‘Pawn to queen’s rook three,’ Calder said, again without looking. The popular line these days, when vodka was your second and you had to play carefully.

Looking at the sparkling chandelier, he hoped he hadn’t been too abrupt with Lidiya earlier that day. She had been waiting for him when he had returned from the Institute, normally docile features animated. Apparently she had joined a queue in Warna, the Bulgarian store on Leninsky, and bought a cherry-coloured dress with a flared skirt. Despite the fact that five hundred other women would be wearing the same dress she was delighted with her purchase and she was wearing it for him.

He was touched. ‘Very pretty,’ he told her.

She smoothed the skirt against her thighs. She had been allotted to him when he first came to Moscow and she had served him well in the apartment, adequately in bed.

Respect had arisen between them although even now he didn’t really know if she enjoyed the love-making: it seemed to him to owe a lot to a Western sex manual given to her to cater for a decadent American’s appetites.

She was a lean woman with surprisingly large breasts. She was frankly plain and might one day look spinsterish, but there was a pleasing serenity about her and her brown hair curled prettily at the nape of her neck.

‘Would you like me to stay?’ she asked him but he told her no, he had work to do, and she departed ostensibly unperturbed, but you could never really tell with Lidiya.