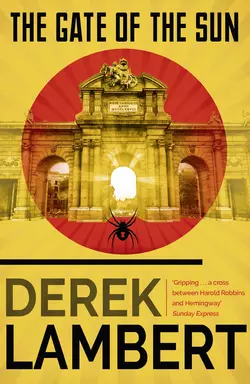

The Gate of the Sun

The Gate of the Sun

Derek Lambert

Spain, over a span of forty turbulent years, is the theatre for a drama of love, friendship, ideals, ambition and revenge in this powerful and passionate novel about the Spanish Civil War by Derek Lambert.

Gripping a cross between Harold Robbins and Hemingway’ Sunday Express

On the bitter battlefields of the Spanish Civil War, an unlikely friendship is forged. Tom Canfield and Adam Fleming are from different countries and on opposing sides, yet they have one thing in common a passionate love for Spain

With a fervour to match their own, a woman is battling in the same bloody struggle. She is Ana, the Black Widow; young, beautiful, bereaved and a dangerous freedom fighter.

The end of the armed conflict will not end the conflicting emotions that draw these people together. For over forty turbulent years, from the dark days of Franco’s victory to the birth of modern Spain, they will be bound together in an intricate web of love betrayal, ambition and revenge

Derek Lambert, who knew and loved Spain for many years, uses his unique understanding of Spanish history and character in this sweeping novel which encompasses some of the most crucial events of twentieth-century Europe, creates characters of extraordinary depth and humanity, and tells a story of compelling power and vitality.

Pure unadulterated story telling’ Daily Telegraph

The Gate of the Sun

Derek Lambert

Copyright (#u53534a36-00d4-5d2e-9bf7-efbfcd353a8e)

Collins Crime Club

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain

by Hamish Hamilton Ltd 1990

Copyright © Estate of Derek Lambert 1990

Cover Design by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018 © HarperCollins Publishers 2018

Cover images © Shutterstock.com (https://www.shutterstock.com)

Derek Lambert asserts the moral right

to be identified at the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008287689

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008287696

Version: 2018-05-09

Dedication (#u53534a36-00d4-5d2e-9bf7-efbfcd353a8e)

For Jonathan, mi hijo

Table of Contents

Cover (#u6b8d1bdb-0f15-514c-83d2-375d12e5e26f)

Title Page (#uddc5c125-553d-552b-9d21-2016e2c0d29f)

Copyright (#u35ffb0e8-10b2-5970-85fa-64d72da14cf4)

Dedication (#ue3ef8456-6adc-5bc5-b754-9aff078820fd)

Author’s Note (#u02803bc0-9751-519c-8229-e569a700cba3)

1975 (#ue1759523-ce34-5de5-83f5-62a6bf72c516)

Prologue (#u245fc779-4a6a-5551-914f-19d4c82dddab)

Part I: 1937–1939 (#u91981672-f193-515a-aa8b-99e60103d8d5)

Chapter 1 (#ud98bc92e-501a-57d7-9139-639e5de44f41)

Chapter 2 (#uaf9256a8-f9d2-5d63-beaf-128a90064bd8)

Chapter 3 (#ua6501dc8-0a20-59a5-a909-2475bf912519)

Chapter 4 (#u20193dc5-9662-57cd-9922-76b8abb2579f)

Chapter 5 (#u27db2c4d-d2a6-5f03-8576-714f06570d75)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II: 1940–1945 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III: 1946–1950 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part IV: 1950–1960 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part V: 1964–1975 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#u53534a36-00d4-5d2e-9bf7-efbfcd353a8e)

There must be an element of masochism in my nature because it would be intimidating enough for a Spaniard to write a novel about the labyrinth (Gerald Brenan’s apposite choice of word) that is Spain, let alone a foreigner. It may also be interpreted by Spaniards as an impudence. What possible pretext can an Englishman proffer for chronicling in fiction 40 years of Spanish history beginning with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1936? My only justification is that I wrote the book because I love Spain and its people, and I seek forgiveness for the mistakes and occasional liberties – the over-simplification in the Civil War of Fascist and Republican was perpetrated in the interests of clarity – that inevitably occur. I would like to believe, however, that I may have arranged the words in such a way that the vibrancy of Spain rises from the pages to obscure such infelicities.

1975 (#u53534a36-00d4-5d2e-9bf7-efbfcd353a8e)

PROLOGUE (#u53534a36-00d4-5d2e-9bf7-efbfcd353a8e)

Every morning the old woman in black packed a Bible in her worn bag, walked to church and prayed for forgiveness.

At first, newcomers drinking coffee and Cognac beneath the hams hanging in the Bar Paraiso questioned her fragile intensity but soon, like the old hands, they accepted her as part of the assembling day, as predictable as the arrival of Alberto, the one-legged vendor of lottery tickets and the screams of abuse from Angelica Perez as her husband scuttled from their apartment above the bakery.

None, unless they could cast their minds back 40 years, would have suspected that she had once set a torch to pews and vestments dragged from another church and spat upon a plump priest as he ran a gauntlet of hatred.

As for the woman she cared nothing for what they thought – scarcely heeded them, or the muted roar of traffic on the M30, or the squawk of the rag seller, as she made her way down a narrow street off the Marqués de Zafra in the east of Madrid.

She was 68 years old but she had spent her passions early and did not carry her years easily. Sometimes she mistook the boom and crackle of fireworks for gunfire, occasionally she confused the uniforms of the city police for the blue monos the militiamen once wore, but she did not dwell in the past. She lived rather in a suspended capsule in which the lengthening years and changing seasons were scarcely acknowledged.

Her hair was a lustrous white, combed tightly into a bun; her gaze, although the focus was remote, was steady; and her face had not yet assumed the fatalistic mask of the old and unwanted.

This bitter winter day she walked at her usual pace that never varied, whether the city was sweating in the heat of August or cowering before the snow-stinging winds of January. And such was the remote authority of her gait that the crowds parted before her as nimbly as pecking pigeons.

When she reached a corner lot, where children played basketball, the walls were daubed with fading graffiti and geraniums hung from pots crowding the balconies, she turned down an alley where, at the end, stood the church, its dome like a blue mushroom.

As she made her way down the street its occupants set their watches by her. A solicitor practising the scrolls of his signature, a purveyor of religious tracts scanning a mildly pornographic magazine, a greengrocer polishing fruit from the Canaries … At 9.18 she would enter the church, pray in the last-but-one pew and emerge at 9.23. What prayer she held in the chapel of her hands no one knew, only that it had been thus for 10 years or more.

But today she walked straight past the open door of the church without so much as a glance inside, causing consternation in this modest thoroughfare. What none of the inhabitants knew was that it was vengeance that had imparted that air of impartial arrogance for all those years and that today, instead of a Bible, she carried a gun in her worn bag.

PART I (#u53534a36-00d4-5d2e-9bf7-efbfcd353a8e)

CHAPTER 1 (#u53534a36-00d4-5d2e-9bf7-efbfcd353a8e)

Difficult to believe on this February morning in 1937 that, as a new day was born in the sky, men on the earth below were dying.

Tom Canfield lowered his stubby little Polikarpov from the cloud to take a closer look, but all he could see were swamps of mist, broken here and there by crests of hills – like the backs of prehistoric monsters, he thought – and the occasional flash of exploding shells.

He nosed the monoplane with its camouflaged fuselage and purple, yellow and red tailplane even lower, as though he were landing on the mist over the Jarama river. Hilltops sped past, vapour slithered over the wings; he had no idea whether he was flying over Fascist or Republican lines, only that the Fascists were trying to cut the road to Valencia, the main supply route to Madrid, 20 miles north-west of the beleaguered capital and had to be stopped.

Three months ago he could not have told you where Valencia was.

Despairing of finding the enemy, he raised the snout of the Polikarpov, known to the Fascists as a rat, and flew freely in the acres between mist and cloud, a tall young man – length sharpened into angles by the confines of the cockpit – with careless fair hair that gave an impression of warmth, and the face of a seeker of truths. The mist was just beginning to thin when he spotted another aircraft sharing the space. He banked and flew towards it and as it grew larger and darker he identified it as an enemy Heinkel 51 biplane.

Enemy? I don’t know the pilot and he doesn’t know me. Why should we, strangers in a foreign land, try and shoot each other out of the wide sky? He adjusted his goggles which were in no need of adjustment and, with the ball of his thumb, touched the button controlling the little rat’s 7.62 mm machineguns.

Wings beat in the cage of his ribs.

He thought the German pilot of the Heinkel waved but he could not be sure. He waved back but he had no idea whether the German could see him.

His chest ached with the beat of the wings.

Tom learned to fly in the good days, in his father’s Cessna at Floyd Bennett Field, before his father was wiped out on Wall Street in the Crash of 1929.

Those were the days when, without pausing to spare good or bad fortune a thought, Tom had lived with his parents in a 32-roomed mansion at Southampton on Long Island, an apartment overlooking Central Park and a cabin at Jackman in Maine, near the Canadian border, where there was a lake stuffed with trout.

One day’s dealings on the Stock Exchange had erased these visible assets, and a lot more besides. Harry Canfield, self-made and bullishly proud of it, had suffered a stroke and his wife had mourned his convalescence with stoic martyrdom; the Cessna had been sold and Tom had quit Columbia Law School to earn a living.

Unprepared for routine labour, he had not prospered, succeeding only as a bouncer in a speakeasy until five Italians beat him senseless and concluding that period of his life share-cropping in Arkansas. By then he had lived in accommodation no bigger than a garden shed in a coal town in West Virginia and subsisted on soup made from potato peelings, and he had stood in a line in sub-zero temperatures in Minnesota waiting for a meal that had evaporated when he reached the head of the queue, and he had shared a brick-built shack in Central Park with commanding views of the blocks where the more fortunate citizens of New York still resided. And he had become rebelliously inclined.

When civil war broke out in Spain in July 1936, he and some 3,000 other Americans identified immediately and passionately with the Republicans – the workers, the peasants, the people – and crossed the Atlantic to help them fight their terrible, fratricidal battles. Some went through the Pyrenees, some reported to the recruiting centre of the International Brigades in Paris on the rue Lafayette.

Tom was interviewed in Paris by a chain-smoking Polish colonel with a shaven scalp and pointed ears who was reputed to have fought for the reds in the Russian civil war. He made notes in an exercise book with a squeaking pen in tiny mauve lettering.

What were Tom’s qualifications?

‘I can fly,’ Tom told him.

‘Aircraft?’ The colonel stared at him through the smoke rising from a yellow cigarette.

‘Boeings,’ Tom said.

‘Stearmans?’

‘P-26s,’ Tom lied because Stearmans were trainers and this shiny-scalped Pole with the exhausted eyes seemed to know his aircraft.

‘Age?’

‘Twenty-five.’

‘What’s the landing speed of a P-26?’

‘High, maybe 75 miles per hour.’

‘Politics?’

‘None.’

The colonel laid down his chewed pen. ‘Everyone has a political attitude whether they realize it or not.’

‘Okay, I’m for the people.’

‘An Anarchist?’

‘Sounds good,’ said Tom who had not thrown up on a cargo boat all the way from New York to Le Havre to be interrogated.

‘Communist?’

Tom shook his head and stared at the rain-wet street outside.

‘Socialist?’

‘If you say so.’

The colonel lit another cigarette, inhaling the smoke hungrily as though it were food. He scratched another entry in the exercise book. ‘Why do you want to fight in Spain?’

Tom pointed at a poster on the wall bearing the words SPAIN, THE GRAVE OF FASCISM.

‘Tell me, Comrade Canfield, are you anti-poverty or anti-riches?’

What sort of a question was that? He said: ‘I believe in justice.’

The colonel dipped his pen into the inkwell and wrote energetically. The rain made wandering rivulets on the window. Lenin smiled conspiratorially at Tom from a picture-frame on the wall.

‘You were born in New York?’

‘Boston,’ Tom said.

‘Why didn’t you go to Harvard?’

‘I went share-cropping instead.’

‘Please don’t play games with me. You see I, too, lived in New York. You’re no peasant, Mister Canfield, not with that accent.’

‘My father went bust.’

‘So why does the son of a capitalist want to fight for the Cause?’

‘Because bad luck is a two-edged sword, comrade. When we were rich I saw only the sea and the sky; when we went broke I saw the land and I saw people trying to make it work for them.’

‘And did it?’

‘I lived in a shack with a married couple with five kids in a coal town in West Virginia. Know what they paid them with?’

The colonel shook his head.

‘Coal,’ Tom said.

‘What were you paid in?’

‘Ideals,’ Tom said. ‘Do you have any objections to those, comrade?’ thinking: ‘Watch your tongue, or you’ll blow it.’

‘Why didn’t you join the Party?’

‘Which party?’

‘There is only one.’

‘You don’t reckon the Democrats or the Republicans?’

‘There’s not much to choose between them, is there? They’re all capitalists.’

‘What do you believe in, Colonel?’

‘In the class struggle. I believe that one day the slaves and not the slave-drivers will rule the world.’

‘Rule, Colonel?’

‘Co-exist. But please, I am supposed to be asking the questions. Do you believe in God?’

‘I guess so. Whether he’s Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish, or Catholic. Or Communist,’ he said.

‘The Fascists believe they have God on their side. Maybe you should fight for the Fascists.’

‘Perhaps I should at that.’

‘I’m afraid we can’t allow that.’ The colonel almost smiled and his pointed ears moved a little. ‘You see, we need pilots.’ He leaned forward and made a small, untidy entry in the exercise book.

At first Paris was a disappointment. The inhabitants of the arrondissement where he was staying resented penniless mercenaries on their streets and the other foreigners taking part in the crusade, particularly the Communists, were hostile to an American who, although he had picked fruit in California and collected duck shit at the east end of Long Island for fertilizer, still possessed the sheen of privilege. He was either slumming or spying.

When one Russian on his way to Spain as an adviser – they were all ‘advisers’, the Russians – accused him in a café of being a spy he resorted to his fists, a not infrequent expedient when his tongue failed him. The Russian, a Georgian with beautiful eyes and a belly like a sack of potatoes, fought well but he was no match for the middle-weight champion of Columbia.

‘So,’ the Russian said from between fist-thickened lips, ‘if you’re not a spy what the hell are you?’ He picked himself up from the wreckage of a table.

‘An idealist, I guess.’

‘With a punch like that?’ The Russian shook his head tentatively and touched one slitted eye. ‘Are you reporting to Albacete?’ Tom said he was. ‘Maybe I will become your commissar,’ continued the Russian. ‘I would like that.’ Followed by other advisers, he walked into the rain-swept street.

When the Russians had gone the sturdy bespectacled man in the corner said, ‘So you pack your ideals in your fists?’

Tom, who was beginning to think that ideals could get him into a lot of trouble, said, ‘He asked for it.’

‘And got it. Where did you learn to fight like that?’ His accent was Brooklyn, as refreshing as water from a sponge.

‘Columbia,’ Tom said, sitting at the table. ‘Where did you learn to talk like that?’

‘A rhetorical question?’

‘Rhetorical, Jesus!’

‘I come from Brooklyn and I mustn’t use long words?’ He beckoned a waiter. ‘Beer?’

‘Fine,’ Tom said, examining a bruised knuckle.

‘You a flier?’

‘Am I that obvious?’

‘I can see it in your eyes. Searching the skies. My name’s Seidler,’ stretching a hand across the table. His grip was unnecessarily strong; when people gripped his hand firmly and looked him straight in the eye Tom Canfield looked for reasons – he had become wise in the coal fields and the orchards.

The waiter placed two beers on the table.

‘Are you going to Spain?’ Tom asked doubtfully because with his spectacles and the roll of flesh under his chin Seidler did not have the bearing of a crusader.

‘To Albacete. Wherever the hell that is.’

‘Why?’ Tom asked.

‘Because Spain seems like a good place to fly.’

‘You’re a pilot? Wearing spectacles?’

‘For reading only.’

‘So why are you wearing them now?’

‘And for drinking beer,’ Seidler said.

‘Okay, stop putting me on. Why are you going to Spain?’

‘Isn’t it obvious? Me, a German Jew, Hitler and Mussolini, Fascists in Spain … Or am I addressing a punch-drunk college dropout?’

‘I used to collect duck shit,’ Tom said.

‘Guano,’ Seidler said. ‘Best goddamn fertilizer in the world.’ He took a deep draught from his glass. ‘So your old man went bust?’

‘How did you know that?’

‘Instinct,’ Seidler said tapping the side of his nose. ‘Who interviewed you? A Polak with pointed ears?’

‘He told you?’

‘Said you were a flier, too.’

‘A very stupid flier,’ Tom said. ‘Eyes searching the skies … Didn’t you have your eyes tested before you started flying?’

‘I’m short-sighted which means I can see long distances.’

‘So?’

‘I keep crashing,’ Seidler said.

After that Tom Canfield enjoyed Paris.

On 28 November Seidler and Canfield departed from the Gare d’Austerlitz on train number 77 on the first stage of their journey to the Spanish city of Albacete which lies on the edge of the plain, half-way between Madrid and the Mediterranean coast.

There were many volunteers on the train, French, British, Germans, Poles, Italians, and Russian advisers. Tom felt ill at ease with the leather-jacketed Russians: he had journeyed to Europe to fight injustice, not espouse Marx or Lenin or, God forbid, Stalin. But, as the train paused at small stations he was comforted by the crowds on the platforms waving banners, offering wine and, with clenched fists raised, chanting, ‘No pasarán!’ – they shall not pass. He was also cheered by the knowledge that he and Seidler were fliers, not foot soldiers; there is, as he was discovering, a pecking order in all things.

‘Tell me how you became a flier,’ he said to Seidler as the train nosed slowly past ploughed, wintry fields. Wine had spilled on his scuffed flying jacket, much shabbier than Seidler’s, and he felt a little drunk – happy to be here in Spain.

‘I wanted to join the Air Force,’ Seidler said, chewing grapes that a well-wisher had handed him and spitting the pips on the floor. ‘Actually volunteered, would you believe? I mean, do I look like Air Force material?’

‘It’s the spectacles,’ Tom said, but it was more.

‘They were polite. “Not quite what we’re looking for, Mr Seidler, but thank you for offering your services.” So I went back to selling books in a discount store on 42nd Street and learned to fly in New Jersey and waited for a war some place.’

Tom pointed at a miniature haystack on a church. ‘What the hell’s that?’

‘A stork’s nest,’ Seidler said. ‘Did you leave a girl behind?’

‘Nothing serious,’ Tom said.

‘Parents?’

‘My father had a stroke after he was cleared out. They live in a small hotel in upstate New York. They didn’t want me to come out here’ – the understatement of the year.

‘And you’re obviously an only child.’

Obviously? He remembered the house on Long Island and he remembered avenues of molten light on the water with yachts making their way down it, and men dressed in shorts and matelot jerseys drinking with his father, fierce moustache trimmed for his 60th birthday, and his mother dutifully reading to him in bed. She had been beautiful then, an older Katherine Hepburn, with chestnut hair piled high. He had never told them that he hated boats and, when he was lying on his back on the deck of the yacht, he was imagining himself at the controls of a yellow biplane exploring the castles of cloud on the horizon.

‘But you’re not,’ he said to Seidler.

‘Two brothers, one sister, all gainfully employed in the Garment Centre.’

The train which they had joined at Valencia stopped at a station, little more than a platform, and a dozen militiamen climbed on board. They wore blue overalls and boots, or rope-soled shoes, and berets or caps – one wore a French-style steel helmet, and two of them sported blood-stained bandages. Although the war had been in progress for only four months they conducted themselves like veterans and one carried a long-barrelled pistol which he laid carefully on his knees, as though it were made of glass. They were all young but they were no longer youthful.

Seidler spoke to them in Spanish. They were, he told Tom, returning to Madrid which had miraculously held out against the Fascist onslaught.

As Seidler talked and handed out Lucky Strikes, which were taken shyly and examined like foreign coins, Tom spread a map on his knees and tried to understand the war.

He knew that the Fascists, or Nationalists, were drawn from the army, the Falange and the Church, the landowners and the industrialists; that the Republicans were Socialists, trade unionists, intellectuals and the working class.

He knew that, to protect their privileges, the Fascists had risen in July 1936 to overthrow the lawful government of the Republic, established in 1931, which was being far too indulgent towards the poor. He had read somewhere that before the advent of the Republic a peasant had earned two or three pesetas a day.

He knew that the Fascists, led by General Francisco Franco, had, with the help of German transport planes, invaded Spain from North Africa and that in the north, led by General Emilio Mola, they had swept all before them. But great swathes of Spain, including the cities of Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia, were still in the hands of the Republicans. No pasarán!

He knew that the Moors fighting for Franco took no prisoners and cut off their victims’ genitals; he knew that the heroine of the Republicans was a woman known as La Pasionaria.

He knew that on the sides of this carriage where, on the wooden seats, peasants sat with their live chickens and baskets of locust beans were scrawled the letters UGT and CNT and FAI, but he had no idea what they meant and was ashamed of his ignorance.

The plain rolled past; water and smuts from the labouring engine streaked the windows.

‘So what else have you found out?’ Tom asked Seidler.

‘That Albacete is the asshole of Spain but they make good killing knives there.’

The militiamen, Tom reflected later, had been right about Albacete. It was cold and commonplace, and the cafés were crammed with discontented members of the International Brigades from many nations drinking cheap red wine.

The garrison was worse. It was the colour of clay, the barrack-room walls were the graveyards of squashed bugs and the floors were laid with bone-chilling stone. Tom and Seidler were quartered with Americans in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion – seamen, students and Communists – but France was in the ascendancy: the Brigade commissar, André Marty, was a bulky Frenchman with a persecution complex; parade-ground orders were issued in French; many uniforms, particularly those worn resentfully by the British, were Gallic leftovers from other conflicts.

He and Seidler complained to Marty the day the commander of the Abraham Lincolns, good and drunk, fired his pistol through a barrack-room ceiling.

From behind his desk Marty, balding with a luxuriant moustache, regarded them suspiciously.

‘You are guests in a foreign country. You shouldn’t complain – just think of what the poor bastards in Madrid are going through.’

‘Sure, and we want to help them,’ Seidler said. ‘But the instructors here couldn’t organize a piss-up in a brewery.’

Marty fiddled with a button on his crumpled brown uniform.

‘You Jewish?’ He sucked his moustache with his bottom lip. ‘And a flier?’ – as though that compounded the crime.

And it was then that Tom Canfield realized that Marty was jealous, that fliers were different and that this would always be an advantage in life.

‘We didn’t come here to march and clean guns: we came here to fly,’ Tom said. He loved the word ‘fly’ and he wanted to repeat it. ‘We came here to bomb the Fascists at the gates of Madrid and shoot their bombers out of the sky. We’re not helping the Cause sitting on our asses; flying is what we’re good at.’

Marty, who was said to have the ear of Stalin, listened impatiently and Tom got the impression that it was Communism rather than the Cause that interested him.

‘I want your passports,’ Marty said.

‘The hell you do.’

‘In case you get shot down. You’re not supposed to be in this war. Article Ten of the Covenant of the League of Nations.’

‘So what about the Russians?’ Tom asked.

‘Advisers,’ Marty said. ‘Give me your passport.’

‘No way,’ Tom said. Then he said, ‘You mean we’re leaving here?’

‘To Guadalajara, north-east of Madrid. You’ll be trained by Soviet advisers. There’s a train this afternoon. On your way,’ said Marty who could do without fliers in his brigade. He flung two sets of documents on the desk. Tom was José Espinosa, Seidler Luis Morales. ‘Only Spaniards are fighting this war,’ Marty said. ‘It’s called non-intervention.’

‘Congratulations, Pepe,’ Seidler said outside the office.

‘Huh?’

‘The familiar form of José.’

Tom scanned his new identification paper. It was in French. Of course. But he still had his passport.

At the last minute the Heinkel from the Condor Legion, silver with brown and green camouflage, ace of spades painted on the fuselage, veered away. Tom didn’t blame the pilot: the Russian-made rats were plundering the skies. Or maybe the pilot was no more a Fascist than he was a Communist and could see no sense in joining battle with a stranger over a battlefield where enough men had died already.

He banked and flew above the dispersing mist, landing at Guadalajara, which the Republicans had captured early in the fighting. Seidler was playing poker in a tent with three other pilots in the squadron’s American Patrol. He was winning but he displayed no emotion; Tom had never heard him laugh.

Tom made his reconnaissance report to the squadron commander – he was learning Spanish but his tongue grew thick with trying – debating whether to mention the Heinkel. If he did the commander would want to know why he hadn’t pursued it.

‘No enemy aircraft?’ asked the commander who had already shot down 11.

‘One Heinkel 51,’ Tom said.

‘You didn’t chase it?’

Tom shook his head.

‘Very wise: he was probably leading you into an ambush.’

Tom fetched a mug of coffee and met Seidler walking across the airfield where Polikarpovs, Chato 1-15 biplanes and bulbous-nosed Tupolev bombers stood at rest. It was cold and weeping clouds were following the Henares river on its run from the mountains.

The trouble with this war in which brothers killed brothers and sons killed fathers, he thought as they walked towards their billet, was that nothing was simple. How could a foreigner be expected to understand a war in which there were at least 13 factions? A war in which the Republicans were divided into Communists and Anarchists and God knows what else. A Communist had recently told him that POUM, Trotskyists he had thought, was in the pay of the Fascists. Work that one out.

They reached the billet and Seidler poured them each a measure of brandy. Tom shivered as it slid down his throat. Then he lay on his iron bedstead and stared at his feet clad in fleece-lined flying boots; at least fliers could keep warm. He had once believed that Spain was a land of perpetual sunshine … Sleet slid down the window of the hut and the wind from the mountains played a dirge in the telephone lines.

Seidler sat on the edge of his own bed, placing his leather helmet and goggles gently on the pillow; only Tom knew the secret of those goggles – the frames contained lenses to compensate for his bad sight.

He stared short-sightedly at Tom and said, ‘So how’d it go?’

‘Okay, I guess.’ He told Seidler, who had already recorded one kill, a Junkers 52 on a bombing mission, about the Heinkel. ‘I’m not sure I wanted to shoot it down.’

‘Know what I felt when I got that Junkers? I thought it was one of those passenger planes in a movie, you know, when Gary Cooper or Errol Flynn is trying to guide it through a storm. And as it caught fire and went into its death dive I thought I saw passengers at the windows. And then I thought that maybe it wasn’t a bomber because those Ju-52s are used as transport planes, too – 17 passengers, maybe more – and maybe I had killed them all. Kids younger than us, maybe.’

‘What you’ve got to do,’ Tom said, ‘is remember what we’re fighting for.’

‘I sometimes wonder.’

‘The atrocities …’

‘You mean our guys, the good guys, didn’t commit any?’

Tom was silent. He didn’t know.

‘In any case,’ Seidler said, ‘I’m supposed to be commiserating with you.’ He poured more brandy. ‘I hear that the Fascists have got a bunch of Fiat fighter planes with Italian crews. And that the Italians are going to launch an attack on Guadalajara.’

‘Where do you hear all these things?’

‘From the Russians,’ Seidler said.

‘You speak Russian?’

‘And Yiddish,’ Seidler said. The hut was suddenly suffused with pink light. ‘Here we go,’ Seidler said as the red alert flares burst over the field.

‘In this?’ Tom stared incredulously at the sleet.

They ran through the sleet which was, in fact, slackening – a luminous glow was now visible above the cloud – and climbed into the cockpits of their Polikarpovs. Tom knew that this time he really was going to war and he wished he understood why.

The Jarama is a mud-grey and thoughtful river that wanders south-east of Madrid in search of guidance. It had given its name to the battle being fought in the valley separating its guardian hills, their khaki flanks threaded in places with crystal, but in truth the fight was for the highway to Valencia which crosses the Jarama near Arganda. On this morose morning in February the Fascists dispatched an armada of Junkers 52s to bomb the bridge carrying this highway over the river.

Tom Canfield saw them spread in battle order, heavy with bombs, and above them he saw the Fiats, the Italians’ biplanes which Seidler had forecast would put in an appearance. He pointed and Seidler, flying beside him, peering through his prescription goggles, nodded and raised one thumb.

The Fiats were already peeling off to protect their pregnant charges and the wings were beating again in Tom Canfield’s chest. He gripped the control column tightly. ‘But what are you doing here?’ he asked himself. ‘Glory-seeking?’ Thank God he was scared. How could there be courage if there wasn’t fear? He waited for the signal from the squadron commander and, when it came, as the squadron scattered, he pulled gently and steadily on the column; soaring into the grey vault, he decided that the fear had left him. He was wrong.

The Fiat came at him from nowhere, hung on behind him. Bullets punctured the windshield. A Russian trainer had told him what to do if this happened. He had forgotten. He heard a chatter of gunfire. He looked behind. The Fiat was dropping away, butterflies of flame at the cowling. Seidler swept past, clenched fist raised. No pasarán! Seidler two, Canfield zero. He felt sick with failure. He kicked the rudder pedal and banked sharply, turning his attention to the bombers intent on starving Madrid to death.

Below lay the small town of San Martín de la Vega, set among the coils of the river and the ruler-straight line of a canal. He saw ragged formations of troops but he couldn’t distinguish friend from foe.

The anti-aircraft fire had stopped – the deadly German 88 mm guns could hit one of their own in this crowded sky – and the fighters dived and banked and darted like mosquitoes on a summer evening.

Tom saw a Fiat biplane with the Fascist yoke and arrows on its fuselage diving on a Polikarpov. As it crossed his sights he pressed the firing button of his machine-guns. His little rat shuddered. The Fiat’s dive steepened. Tom watched it. He bit the inside of his lip. The dive steepened. The Fiat buried its nose in a field of vines, its tail protruding from the dark soil. Then it exploded.

Tom was bewildered and exultant. And now, above a hill covered with umbrella pine, he was hunting, wanting to shoot, wasting bullets as the Fiats escaped from his sights. So close were they that it seemed that, if the moments had been frozen, he could have reached out and shaken the hands of the enemy pilots. But it had been a mistake to try and get under the bombers; instead he attacked them from the side. He picked out one, a straggler at the rear of his formation. A machine-gun opened up from the windows where Seidler had imagined passengers staring at him; he flew directly at the gun-snarling fuselage, fired two bursts and banked. The Junkers began to settle; a few moments later black smoke streamed from one of its engines; it settled lower as though landing, then, as it began to roll, two figures jumped from the door in the fuselage. The Junkers, relieved of their weight, turned, belly up, turned again, then fell flaming to the ground. Parachutes blossomed above the two figures.

Without looking down he saw again the white, naked faces of Spaniards killing each other, and reminded himself that among them were Americans and Italians and British and Russians, and wondered if the Spaniards really wanted the foreigners there, if they would not prefer to settle their grievances their own way, and then a Fiat came in from a pool of sunlight in the cloud and raked his rat from its gun-whiskered nose to its brilliant tail.

The Polikarpov was a limb with severed tendons. Tom pulled the control column. Nothing. He kicked the rudder pedal. Nothing. Not even the landing flaps responded. One of his arms was useless, too; it didn’t hurt but it floated numbly beside him and he knew that it had been hit. The propeller feathered and stopped and the rat began its descent. With his good hand Tom tried to work the undercarriage hand-crank, but that didn’t work either. Leafless treetops fled behind him; he saw faces and gun muzzles and the wet lines of ploughed soil.

He pulled again on the column and there might have been a slight response, he couldn’t be sure. He saw the glint of crystal in the hills above him; he saw the white wall of a farmhouse rushing at him.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_202bb53c-0494-5513-ae32-38a847a5c333)

Ana Gomez was young and strong and black-haired and, in her way, beautiful but there was a sorrow in her life and that sorrow was her husband.

The trouble with Jesús Gomez was that he did not want to go to war, and when she marched to the barricades carrying a banner and singing defiant songs she often wondered how she had come to marry a man with the spine of a jellyfish.

Yet when she returned home to their shanty in the Tetuan district of Madrid, and found that he had foraged for bread and olive oil and beans and made thick soup she felt tenderness melt within her. This irritated her, too.

But it was his gentleness that had attracted her in the first place. He had come to Madrid from Segovia because it had called him, as it calls so many, and he worked as a cleaner in a museum filled with ceramics and when he wasn’t sweeping or delicately dusting or courting her with smouldering but discreet application he wrote poetry which, shyly, he sometimes showed her. So different was he from the strutting young men in her barrio that she became at first curious and then intrigued, and then captivated.

She worked at that time as a chambermaid in a tall and melancholy hotel near the Puerta del Sol, the plaza shaped like a half moon that is the centre of Madrid and, arguably, Spain. The hotel was full of echoes and memories, potted ferns and brass fittings worn thin by lingering hands; the floor tiles were black and white and footsteps rang on them briefly before losing themselves in the pervading somnolence.

Ana, who was paid 10 pesetas a day, and frequently underpaid because times were hard, was arguing with the manager about a lightweight wage packet when Jesús Gomez arrived with a message from the curator of the museum who wanted accommodation for a party of ceramic experts in the hotel. Jesús listened to the altercation, and was waiting outside the hotel when Ana left half an hour later.

He gallantly walked beside her and sat with her at a table outside one of the covered arcades encompassing the cobblestones of the Plaza Mayor and bought two coffees served in crushed ice.

‘I admired the way you stood up to that old buzzard,’ he said. He smiled a sad smile and she noticed how thin he was and how the sunlight found gold flecks in his brown eyes. Despite the heat of the August day he wore a dark suit, a little baggy at the knees, and a thin, striped tie and a cream shirt with frayed cuffs.

‘I lost just the same,’ she said, beginning to warm to him. She admired his gentle persistence; there was hidden strength there which the boy to whom she was tacitly betrothed, the son of a friend of her father’s, did not possess. How could you admire someone who pretended to be drunk when he was still sober?

‘You should ask for more money, not complain that you have been paid less.’

‘Then I would be sacked.’

‘Then you should complain to the authorities and there would be a strike in all the hotels and a general strike in Madrid. We shall be a republic soon,’ said Jesús, giving the impression that he knew of a conspiracy or two.

Much later she remembered those words uttered in the Plaza Mayor that summer day when General Miguel Primo de Rivera still ruled and Alfonso XIII reigned; how much they had impressed her, too young even at the age of 22 to recognize them for what they were.

‘My father says we will not be any better off as a republic than we are now.’ She sucked iced coffee through a straw. How many centimos had it cost him in this grand place? she wondered.

‘Then your father is a pessimist. The monarchy and the dictatorship will fall and the people will rule.’

On 14 April 1931, a republic was proclaimed. But then the Republicans, who wanted to give land to the peasants and Catalonia to the Catalans and a living wage to the workers and education to everyone, fell out among themselves and, in November 1933, the Old Guard, rallied by a Catholic rabble-rouser, José Maria Gil Robles, returned to power. Two black years of repression followed and a revolt by miners in Asturias in the north was savagely crushed by a young general named Francisco Franco.

But at first, in the late 20s, before Primo de Rivera quit and the King fled, Ana and Jesús Gomez were so absorbed in each other that, despite the heady predictions of Jesús, they paid little heed to the fuses burning below the surface of Spain; in fact it wasn’t until 1936 that Ana discovered her hatred for Fascists, employers, priests, anyone who stood in her way.

When Jesús proposed marriage Ana accepted, ignoring the questions that occasionally nudged her when she lay awake beside her two sisters in the pinched house at the end of a rutted lane near the Rastro, the flea-market. Why after nearly a year was he still earning a pittance in the perpetual twilight of the museum whereas she, at his behest, had demanded a two-peseta-a-day pay rise and been granted one by an astounded hotel manager? Why did he not try to publish the poems he wrote in exercise books? Why did he not join a trade union, because surely there was a place for a museum cleaner somewhere in the ranks of the CNT or UGT?

They were married during the fiesta of San Isidro, Madrid’s own saint. The ceremony, attended by a multitude of Ana’s family, and a handful of her fiancé’s from Segovia, was performed in a frugal church and cost 20 pesetas; the reception was held in a café between a tobacco factory and a foundling hospital owned by the father of Ana’s former boyfriend, Emilio, who fooled everyone by getting genuinely drunk on rough wine from La Mancha.

Emilio, whose black hair was as thick as fur, and who had been much chided by his companions for allowing the vivacious and wilful Ana to escape, accosted the bridegroom as he made his way with his bride to the old Ford T-saloon provided by Ana’s boss. He stuck out his hand.

‘I want to congratulate you,’ he said to Jesús. ‘And you know what that means to me.’ He wore a celluloid collar which chafed his thick neck and he eased one finger inside it to relieve the soreness.

Jesús accepted the handshake. ‘I do know what it means to you,’ he said. ‘And I’m grateful.’

‘How would you know what it means to me?’ Emilio tightened his grip on the hand of Jesús, becoming red in the face, though whether this was from exertion or wine circulating in his veins was difficult to ascertain.

‘Obviously it must mean a lot,’ Jesús said, trying to withdraw his hand.

Ana, who had changed from her wedding gown into a lemon-yellow dress, waited, a dry excitement in her throat. The three of them were standing between the café where the guests were bunched and the Ford where the porter from the hotel stood holding the door open. No-man’s-land.

‘It means a lot to me,’ Emilio said thickly, ‘because Ana promised herself to me.’

‘Liar,’ Ana said.

‘Have you told him what we did together?’

‘We did nothing except hang around while you pretended to get drunk.’ What she had seen in Emilio she couldn’t imagine. Perhaps nothing: their union had been decided without any reference to her.

Emilio continued to grip the hand of Jesús, the colour in his cheeks spreading to his neck. Jesús had stopped trying to extricate his hand and their arms formed an incongruous union, but he showed no pain as Emilio squeezed harder.

The group outside the café stood frozen as though posing for a photographer who had lost himself inside his black drape.

‘We did a lot of things,’ Emilio grunted.

The porter from the hotel, who wore polished gaiters borrowed from a chauffeur and a grey cap with a shiny peak, moved the door of the Ford slowly back and forth. Fireworks crackled in the distance.

Jesús, thought Ana, will have to hit him with his left fist – a terrible thing to happen on this day of all days but what alternative did he have?

Jesús smiled. Smiled! This further aggrieved Emilio.

‘You would be surprised at the things we did,’ he said squeezing the hand of Jesús Gomez until the knuckles on his own fist shone white.

Finally Jesús, his smile broadening with the pleasure of one who recognizes a true friend, said, ‘Emilio, I accept your congratulations, you are a good man,’ and began to shake his imprisoned hand up and down.

‘Cabrón,’ Emilio said.

‘God go with you.’

‘Piss in your mother’s milk.’

‘Your day will come,’ Jesús said, a remark so enigmatic that it caused much debate among the other guests when they returned to their wine.

The two men stared at each other, hands rhythmically rising and falling, until finally Emilio released his grip and, massaging his knuckles, stared reproachfully at Jesús Gomez.

Jesús saluted, one finger to his forehead, turned, waved to the silent guests, proffered his arm to his bride and led her to the waiting Ford.

From the bathroom of the small hostal near the Caso de Campo, she said, ‘You handled that Emilio very well. He is a pig.’

She took the combs from her shining black hair and shed her clothes and looked at herself in the mirror. In the street outside a bonfire blazed and couples danced in its light. Would he ask her about those things that Emilio claimed they had done together?

‘Emilio’s not such a bad fellow,’ Jesús said from the sighing double bed. ‘He was drunk, that was his trouble.’

Didn’t he care?

‘He is a great womanizer,’ Ana said.

‘I can believe that.’

‘And a brawler.’

‘That too.’

She ran her hands over her breasts and felt the nipples stiffen. What would it be like? She knew it wouldn’t be like the smut that some of the married women in the barrio talked while their husbands drank and played dominoes, not like the Hollywood movies in which couples never shared a bed but nevertheless managed to produce freckled children who inevitably appeared at the breakfast table. She wished he had hit Emilio and she knew it was wrong to wish this.

In novels, the bride always puts on a nightdress before joining her husband in the nuptial bed. To Señora Ana Gomez that seemed to be a waste of time. She walked naked into the white-washed bedroom and when he saw her he pulled back the clean-smelling sheet; she saw that he, too, was naked and, for the first time, noticed the whippy muscles on his thin body, and in wonderment, and then in abandonment, she joined him and it was like nothing she had heard about or read about or anticipated.

It is true that Ana Gomez only encountered her hatred during the Civil War, but it must have been growing sturdily in the dark recesses of her soul to show its hand so vigorously.

When, slyly, was it conceived? In the black years, when one of her three brothers was beaten up by police, losing the sight of one eye, for rallying the dynamite-throwing miners of Asturias? When, at the age of 62, her father, a gravedigger, bowed by years of accommodating the dead, was sacked by the same priest who had married her to Jesús for taking home the dying flowers from a few graves? Or because the same fat-cheeked incumbent had declined to baptize her first-born, Rosana, because she had not attended mass regularly, although for a donation of 20 pesetas he would reconsider his decision … Ah, those black crows who stuffed the rich with education and starved the poor. Ana believed in God but considered him to be a bad employer.

As the hatred, unrecognized, fed upon itself. Ana noticed changes in her appearance. Her hair, pinned back with tortoiseshell combs, still shone with brushing, the olive skin of her face was still unlined and her body was still young, but there was a fierce quality in her expression that was beyond her years. She attributed this to the inadequacies of her husband.

Not that he was indolent or drunken or wayward. He cooked and scavenged and cleaned and Rosana and Pablo, who was one year old, loved him. But he cared only to exist, not to advance. Why did he not write his sonnets in blood and tears instead of pale ink? wondered Ana who, since the heady days of courtship and consummation, had begun to ask many questions. It was she who had found the shanty in Tetuan, it was she who had found him a job paying five pesetas a week more than the National Archaeological Museum. But his bean soup was still the finest in Madrid.

When the left wing, the Popular Front, once again dispatched the Old Guard five months before the Civil War, Ana understood perfectly why strikes and blood-letting swept the country. The prisoners released from jail wanted revenge; the peasants wanted land; the people wanted schools; the great congregation of Spain wanted God but not his priests. What she did not understand were the divisions within the Cause and, although she reacted indignantly as blue-shirted youths of the Falange, the Fascists, terrorized the streets of the capital, she still didn’t acknowledge the hatred that was reaching maturity within herself.

On May Day, when a general strike had been called, she left the children with her grandmother and, with Jesús, who accompanied her dutifully but unenthusiastically, and her younger brother, Antonio, marched down the broad paseo that bisects Madrid, in a procession rippling with a confusion of banners. One caught her eye: ANTI-FASCIST MILITIA: WORKING WOMEN AND PEASANT WOMEN – red on white – and the procession was heady with the chant of the Popular Front: ‘Proletarian Brothers Unite’. In the side streets armed police waited with horses and armoured cars.

Musicians strummed the Internationale on mandolins. Street vendors sold prints of Marx and Lenin, red stars and copies of a new anti-Fascist magazine dedicated to women. And indeed women marched tall as the widows of the miners from Asturias advanced down the promenade. The colours of the banners and costumes were confusing – blue and red seemed to adapt to any policy – and occasionally, among the clenched fists, a brave arm rose in the Fascist salute.

After the parade the hordes swarmed across Madrid, through the West Park and over the capital’s modest river, the Manzanares, to the Casa de Campo, a rolling pasture of rough grass before the countryside proper begins. There they planted themselves on the ground, boundaries defined by ropes or withering glances, released the whooping children and foraging babies, tore the newspapers from baskets of bread and ham and chorizo, passed the wine and bared their souls to the freedom that was soon to be theirs.

Ana pitched camp between a pine and a clump of yellow broom where you could see the ramparts of the city, the palace and the river below, and, to the north, the crumpled, snow-capped peaks of the Sierra de Guadarrama.

Her happiness as she relaxed among her people, her Madrileños, who were soon to have so much, was dispatched by her brother after his third draught of wine from the bota. As the jet, pink in the sunshine, died, he wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and said, ‘I have something to tell you both. A secret,’ although she knew from the pitch of his voice that its unveiling would not be an occasion for rejoicing.

Antonio, one year her junior, had always been her favourite brother. And he had remained so, even when he married above himself, got a job, thanks to his French father-in-law in the Credit Lyonnais where, with the help of the bank’s telephones, he also traded in perfume, and mixed with a bourgeois crowd. He was tall, with tight-curled, black hair, a sensuous mouth and a nimble brain; his cheeks often smelled of the cologne in which he traded.

‘I have joined the Falange,’ he said.

It was a bad joke; Ana didn’t even bother to smile. Jesus took the bota and directed a jet of wine down his throat.

‘I mean it,’ Antonio said.

‘I knew this wine was too strong; it has lent wings to your brains,’ Ana said.

‘I mean it, I tell you.’ His voice was rough with pride and shame.

There was silence beneath the pine tree. A diamond-shaped kite flew high in the blue sky and a bird of prey from the Sierra glided, wings flattened, above it.

Ana said, ‘These are your wife’s words. And her father’s.’

‘It is I who am talking,’ said Antonio.

‘You, a Fascist?’ Ana laughed.

‘You think that is funny? In six months time you will be weeping.’

‘When you are taken out and shot. Yes, then I will weep.’ She turned to Jesús but he had settled comfortably with his head on a clump of grass and was staring at the kite which dived and soared in the warm currents of air.

Antonio leaned forward, hands clenched round his knees; he had taken off his stylish jacket and she could see a pulse throbbing in his neck. She remembered him playing marbles in the baked mud outside their home and throwing a tantrum when he lost.

He said, ‘Please listen to me. It is for your sake that I am telling you this.’

‘Tell it to your wife.’

‘Listen, woman! This is a farce, can’t you see that? The Popular Front came to power because enemies joined forces. But they are already at blows. How can an Anarchist who believes that “every man should be his own government” collaborate with a Communist who wants a bureaucratic government? As soon as the war comes the Russians, the Communists, will start to take over. Do you want that?’

‘Who said anything about a war?’

‘There is no doubt about it,’ Antonio said lighting a cigarette. ‘Within months we will be at war with each other.’

‘Who will I fight against? A few empty-headed Fascists in blue shirts?’

‘Listen, my sister. We cannot sit back and watch Spain bleed to death. The strikes, the burnings, the murders, the rule of the mob.’ He stared at the black tobacco smouldering in his cigarette. ‘We have the army, we have the Church, we have the money, we have the friends …’

‘Friends?’

‘I hear things,’ said Antonio who had always been a conspirator. ‘And I tell you this: the days of the Republic are numbered.’

Jesús, eyes half closed, said, ‘I am sure everything will sort itself out.’ He had taken a notebook from his pocket and was writing in it with an indelible pencil.

‘You were a Socialist once,’ Ana said to Antonio.

‘And I was poor. If I had stayed a Socialist or a Communist or an Anarchist I would have stayed poor. How many uprisings have there been in the past 50 years? What we need is stability through strength!’

‘And who will give that to us?’ She took the bota from her husband, poured inspiration down her throat. Her brother a Fascist? What about their brother, the sight knocked out of one eye by a police truncheon? What about their father, sacked by a priest with a trough of gold beneath his church? What about the miners, with their homemade bombs, gunned down by the military? What about the peasant paid with the chaff of the landowners’ corn?

‘There are many good men waiting to take command.’

‘Of what?’

‘I have said enough,’ Antonio said.

Jesús, licking the pencil point, said, ‘Good sense will prevail. Spain has seen too much violence.’

‘Spain was fashioned by violence,’ Antonio said. ‘But now a time for peace is upon us. After the battle ahead,’ he said. ‘Join us. The fighting will be brief but while it rages you can take the children into the country.’

She stared at him in astonishment. ‘Have you truly lost your senses?’

‘Life will be hard for those who oppose us.’

‘Threats already? A time for peace is upon us?’

Jesús said, ‘The milk of mother Spain is blood.’ He wrote rapidly in his notebook.

Antonio poured more wine down his throat and stood up, hands on hips. ‘I have tried,’ he said. ‘For the sake of you and your husband and your children. If you change your mind let me know.’

‘Why ask me? Why not ask my husband?’

Antonio didn’t reply. He began to walk down the slope towards the Manzanares dividing the parkland from the heights of the city.

When he was 50 metres away from her she called to him. The diamond-shaped kite dived and struck the ground; the bird of prey turned and flapped its leisurely way towards the mountains.

‘What is it?’

He stood there, suspended between distant childhood, and adulthood.

She raised her arm, bunched her fist and shouted, ‘No pasarán!’

The militiamen came for the priest at dawn, a dangerous time in the lawless streets of Madrid in the summer of 1936. Failing to find him, they turned on his church.

The studded doors gave before the fourth assault with a sawn-off telegraph pole. Christ on his altar went next, battered from the cross with the butt of an ancient rifle. They tore a saint and a madonna from two side chapels and trampled on them; they dragged curtains and pews into the street outside and made a pyre of them; they smashed the stained-glass window which had shed liquid colours on the altar as Ana and Jesus stood before the plump priest at their wedding. They were at war, these militiamen in blue overalls, some stripped to the waist, and a terrible exaltation was upon them.

Ana, who knew where the priest was, watched from the gaping doors and could not find it in herself to blame the wild men who were discharging the accumulated hatred of decades. Since the Fascist rising on July 17 the ‘Irresponsibles’ in the Republican ranks had butchered thousands and invariably it was the clergy who were dispatched first. Ana had heard terrible tales; of a priest who had been scourged and crowned with thorns, given vinegar to drink and then shot; of the exhumed bodies of nuns exhibited in Barcelona; of the severed ear of a cleric tossed to a crowd after he had been gored to death in a bullring.

But although she understood – the flowers that her father had taken from the graves of the privileged had been almost dead – such happenings sickened her and she could not allow them to happen to the priest hiding in the vault of the church with the gold and silver plate.

The leader of the gang, the Red Tigers, shouted, ‘If we cannot find the priest then we shall burn the house of his boss.’ He had the starved features of a fanatic; his eyes were bloodshot and his breath smelled of altar wine.

Ana, to whom blasphemy did not come easily, said, ‘What good will that do, burro, burning God’s house?’

‘He has many houses,’ the leader said. ‘Like all Fascists.’ He thrust a can of gasoline into the hand of a bare-chested militiaman who began to splash it on the walls. ‘What has God ever done for us?’

‘He did you no harm, Federico. You have not done so badly with your olive oil. How much was it per litre before the uprising?’

He advanced upon her angrily but spoke quietly so that no one else could hear him. ‘Shut your mouth, woman. Do you want that scribbling husband of yours shot for collaborating with the Fascists?’

‘As if he would collaborate with anyone. No one would believe you. They would think you were trying to take his place in my bed.’

‘The olive oil,’ the leader said more loudly, ‘is 30 centimos a litre. Who can say fairer than that?’

‘I asked what it was.’

‘So you know where the priest is?’ he shouted as though she had confessed and the militiamen paused in their pillaging and looked at her curiously.

She stared into the nave of the church where, with her parents and her brothers, she had prayed for a decent world and a reprieve for a stray alley cat and for her grandfather whose lungs played music when he breathed. She remembered the boredom of devotion and the giggles that sometimes squeezed past her lips and the decency of it all. She stepped back so that she could see the blue dome. A militiaman attacking a confessional with an axe shouted. ‘Do you know where the priest is, Ana Gomez?’

And it was then that Ana Gomez was visited by a vision of herself: one fist clenched, head held high, the fierceness that had been in gestation delivered. She told Federico to drag a pew from the pile in the street and when, grumbling, he obeyed, she stood on it.

She said, ‘Yes, I do know where the priest is,’ and before they could protest she held up one hand. ‘Hear me, then do what you will.’

As they fell silent she pointed at one young man with the tanned skin and hard muscles of a building labourer: ‘You, Nacho, were married in this church, were you not?’ And, when he nodded, ‘Then your children are the children of God and this is their house. Can you stand back and see it burned?’ He unclenched one big fist and stared at the palm in case it contained an answer.

‘And you,’ to a white-fleshed man whose belly sagged over his belt, ‘should be ashamed. Wasn’t your mother buried in the graveyard behind the church barely two weeks ago? Do you want her soul to go up in flames?’

‘And you,’ to a youth who had filled his pockets with candles, ‘put those back. Don’t you know they are prayers?’ She paused, waited while he took back the candles which cost ten centimos each.

When he returned she raised both hands. ‘Our fight is not against God: it is against those who have prostituted his love. If you take up arms against God you are destroying yourselves because you came into this world with his blessing.’

‘So the priest who grew fat while we starved should not be punished?’ Federico demanded.

They looked at her, these vandals, and there was a collective pleading in their gaze.

Again she waited. Raised one arm, clenched her fist.

‘Of course he must be punished. So must all the other black crows who betrayed the Church. Beat him, spit on him’ – they wouldn’t settle for less – ‘but don’t degrade yourselves. Why stain your hands with the blood of one fat hypocrite?’

They cheered and she watched the muscles move on their lean ribs, and she saw the light in their eyes.

‘Where is he?’ demanded Nacho.

Another pause. Then, ‘Beneath your feet.’ They stared at the baked mud. ‘In the vaults. With the gold and silver.’

‘Who has the key?’

‘The fat priest. Who else?’ She placed her hands on her hips. ‘Don’t worry. I’ll get him.’

She went into the church. Long before the priest had started to squirrel the altar plate in the vaults he had given her father a key; she had it in her hand now as she made her way through the vestry to the door. The key turned easily; in the thin light filtering through a barred window she saw a kneeling figure.

The priest said, ‘So it has come to this,’ and she thought, ‘Please God don’t let him plead.’ ‘Here, take this.’ He handed her a gold chalice. ‘And help me.’

She distanced herself from him and said, ‘This is what you must do. When you emerge in the sunlight they’ll beat you and scream at you and spit on you. Run as if the wrath of God is behind you’ – which it must be, she thought – ‘and make your way to the old house where I used to live.’

‘They’ll kill me,’ the priest said. As her eyesight became accustomed to the gloom she saw that his plump cheeks had sagged into pouches. ‘And make me dig my own grave.’

She wanted to say, ‘My father could do it for you if you hadn’t sacked him,’ but instead she said, ‘Give them the gold and silver, that will speed you on your way.’

‘It’s a trap,’ the priest said. He bowed his head and gabbled prayers. ‘How can they hate me like this? I have been a good priest to them.’

‘That is for God to decide.’

‘You are a good woman,’ the priest said, standing up.

She handed him back the chalice. ‘Take this and the other ornaments and follow me.’

He said, ‘I wish I were brave,’ and she wished he hadn’t said that because it made her think of her husband.

‘If you believe,’ she said, ‘if you truly believe then you need not fear.’

‘Do you believe, Ana Gomez?’

‘In a fable? A black book full of stories? Angels with wings and a devil who lives in a dark and deep place? Yes, I believe,’ she said and led the way out of the vaults.

In the vestry she ripped up a surplice, wrapped it round the leg of a shattered chair, dipped it in gasoline and lit it with a match. She picked up a green and gold vestment, soaked that in gasoline and, torch carried high in one hand, vestment in the other, emerged into the sunlight.

The mob stared at her, confused. She threw the vestment on the pyre; the gold thread glittered in the sunlight. She applied the torch to it. Flames leaped across the cloth, swarmed over the gasoline-soaked fixtures of the church. Thick smoke rose and sparks danced in it.

She turned and signalled to the priest lurking in the church. He had removed his clerical collar and he was wearing a grey jacket and trousers and big black boots, and was more clown than cleric. His eyes narrowed in the sunlight, his dewlap quivered.

He threw the altar plate at the foot of the flames and began to run. She spat at him, threw the torch on the pyre and ran towards the gold and silver.

The crowd hesitated; then those at the front made a dash for the booty. Federico, the leader, held aloft a gold salver. ‘And we had to count our centimos,’ he shouted.

Then they were after the priest as, weaving and stumbling, he reached the edge of the poor square. Some made a gauntlet in front of him; rifle butts and axe handles smote him on the shoulders. He tried to protect his face with his plump hands but he uttered no sound. Ana reached him and spat again and hissed to him to run down an alley to his left.

She blocked the alley. ‘To think we obeyed such a donkey,’ she cried and indeed he looked too absurd to pursue.

She listened to the receding clatter of his boots on the cobblestones. The pursuers hesitated and, frowning, looked to each other for guidance.

Federico pushed his way through them. ‘Out of the way, woman,’ he said. ‘We must have the priest.’

‘You will have to move me first.’ She folded her arms across her breast and stared at him.

He advanced upon her but as he reached her a burning pew slipped from the pyre belching flames like cannon fire, and smoke heavy with ash billowed across the square.

Ana raised her arms above her head. ‘It is God’s word.’

As they dispersed she returned to the church, locked the door and made her way down rutted lanes to the house where the priest was waiting for her.

She had listened to La Pasionaria broadcasting on Radio Madrid. ‘The whole country throbs with rage in defiance … It is better to die on your feet than to live on your knees.’

And on 20 July she had stood ready to die in the Plaza de España, where Don Quixote’s lance pointed towards the Montana Barracks in which Fascist troops were beleaguered – Fascists later pointed out that Quixote’s outstretched arm closely resembled a Fascist salute – and she had moved inexorably forward with the mob as they stormed the garrison.

She had watched the troops being butchered, although many, it was learned later, had been loyal to the Republicans, and she had watched a marksman drop officers from a gallery high in the red and grey barracks on to the ground.

She had heard about the Republican execution squads, the bodies piled up in execution pits at the university and behind the Prado – more than 10,000 in one month, it was rumoured – and she had wondered if her brother, Antonio, had been among them because although the bourgeoisie and the priests were fair game there was no more highly prized victim than a Falangist.

And she had heard about the inexorable progress of the Fascists in the south, under the command of General Francisco Franco with his Army of Africa – crack Spanish troops in the Foreign Legion whose battle cry was ‘Long live death’ and Moors who raped when they weren’t killing – and General Emilio Mola’s four columns in the north.

To Mola fell some of the responsibility for the killings in Madrid. Hadn’t he boasted, ‘In Madrid I have a Fifth Column: men now in hiding who will rise and support us the moment we march,’ thus inciting the gunmen, many of them criminals released from jail in an earlier amnesty, to further blood-letting? He had also boasted to a newspaper correspondent that he would drink coffee with him in the Puerta del Sol, so every day coffee was poured for him at the Molinero café.

She had doled out bread to refugees roaming the capital, in the sweating alleys of its old town, on the broad avenues of its heartland, and when the first aircraft, three Ju-52s, had bombed the city on 27 August she had organized air-raid precautions for the barrio – shatter-proofing windows with brown paper, painting street lamps blue, making cellars habitable.

So what am I doing drinking coffee in my old home with the enemy, a priest?

Her brother, a street cleaner whose eye had been knocked out long ago by the police, railed. ‘What is this fat crow doing here? He should have been crucified like all the other sons of whores.’

Salvador harboured a bitterness that was difficult for anyone with two eyes to understand, Ana thought. The patch over the socket stared at her blackly. Salvador hosed down streets at dawn but often his aim was bad.

She said quietly, ‘He baptized you and he married me and he listened to our sins.’

‘Did he ever listen to his own? Did he ever do penance?’

The priest, cheeks trembling as he spoke, said, ‘I did my best for all of you. For all of my flock.’

‘For my eye?’

‘That was none of my doing.’

‘Did you pray for the miners in Asturias?’

‘I pray for Mankind,’ the priest said.

‘Ah, the Kingdom of God. We have to pay high rents to occupy it, father.’

‘Jesus was the son of a carpenter. A poor man.’

‘But, unlike us, he could work miracles. Why did you only educate the rich, father?’

‘We have made mistakes,’ the priest admitted.

This took Salvador by surprise. He adjusted his black patch, good eye staring at Ana accusingly. The three of them, and her father who was dying on the other side of the thin wall, were the only people in the house. The house was a hovel but that had never occurred to her when they had been a family. The patterned tiles on the floor were worn; the whitewashed walls had been moulded with the palms of plasterers’ hands and, since her mother’s death, dust had collected in the hollows.

Salvador lit a cigarette and puffed fiercely. ‘I shall have to report his presence to the authorities,’ he said.

‘Which authorities?’

This bothered him too, as Ana had known it would. Before July he had supported the Socialist Trade Union. But now he suspected that Communists were infiltrating it – Russians who had forged tyranny instead of liberty from their Revolution. And they in their turn were at odds with the anti-Stalin Communists.

So Salvador was beginning to move towards the Anarchists, who believed in freedom through force, and didn’t give a damn about political power.

Already families were divided between the Fascists and the Republicans. Please God, Ana prayed while the priest shakily sipped his coffee, do not let the Cause divide us too.

‘The police,’ Salvador said lamely.

‘Which police? There are many of those, too.’

‘Stop trying to confuse me,’ Salvador said. ‘Get rid of him,’ he said pointing at the priest.

‘Kill him?’

‘Just get rid of him. I don’t want to see his face round here.’

‘Since when was it your home?’

‘You think our father would want a priest, that priest, here?’

‘I don’t know what our father would want,’ Ana said.

‘You realize,’ he said, touching his black patch, ‘that we are now the revolutionaries?’

‘Weren’t we always, in spirit?’

‘Now we are doing something about it and we have the Fascist insurgents to thank for it. We are taking over the country.’

‘Do you think the Fascists know about that?’ Ana asked, and the priest said, ‘We are all God’s people,’ and Salvador said, ‘So why are we fighting each other?’

Ana and Salvador looked deeply at each other but they did not speak about Antonio, their brother who had betrayed them. Had he managed to reach Fascist armies in the north or south? It was possible: certainly Republicans trapped behind Fascist lines were reaching Madrid. Salvador pushed back the top of his blue monos exposing his right shoulder. ‘Do you know what that is?’ pointing at bruised flesh.

‘Of course,’ said Ana who knew that he wanted a distraction from their brother. ‘The recoil of a rifle butt.’

‘The badge of death,’ Salvador said. ‘That’s what the Fascists look for when they capture a town. Anyone with these bruises has been fighting against them and they kill them. In Badajoz they herded hundreds with these bruises into the bullring and mowed them down with machine-guns.’

‘You have been firing a rifle?’ Ana looked at him with disbelief. ‘With one eye?’

‘Think about it,’ Salvador said. ‘When you fire a rifle do you not close one eye?’

‘Where have you been firing a rifle?’ she asked suspiciously.

‘Not, who have I been shooting?’ He smiled, one eye mocking. ‘Don’t worry, I’m not a murderer. Not yet. There’s a range on the Casa de Campo and I have been practising.’

From the other side of the wall they heard a moan.

Ana, followed by Salvador, went to their father who was dying from tuberculosis. He looked like an autumn leaf lying there, Ana thought. His grey hair grew in tufts, his deep-set eyes gazed placidly at death. On the table beside him stood a bottle of mineral water and a bowl in which to spit. His prized possession, a stick with an ivory handle shaped like a dog’s head, lay on the stiff clean sheet beside him. He was 67 years old and he looked 80; his mother-in-law, who walked in that moment, would outlive him.

He acknowledged his children with a slight nod of his head and stared beyond them.

‘Is there anything you want?’ Ana asked.

A slight shake of his head.

Salvador took one of his hands, a cluster of bones covered with loose skin, and pressed it gently. ‘We are winning the war,’ he said but the old man didn’t care about wars. He closed his eyes, kept them shut for a few moments, then opened them. Some of his lost expression returned and there was an angle to his mouth that might have been a smile. Ana turned. The priest stood behind them. Salvador rounded on him but Ana put her finger to her lips. He stretched out one hand and the priest who had taken away his living for stealing a few expiring blossoms held it.

‘May God be with you,’ the priest said.

Back in the living-room the priest said, ‘I think it would be a good thing if I stayed. I can administer the last rites.’

Salvador wet one finger, drew it across his own throat, and said, ‘But who will administer them to you?’

Ana’s sister-in-law, Antonio’s wife, came to her home one late September day. She had discarded the elegant clothes that Ana associated with girls in Estampa and her permanent waves had spent themselves; she was pregnant, her ankles were swollen. Ana regarded her with hostility.

‘Slumming, Martine Ruiz?’ she demanded at the door. Not that the shanty was a slum; it might not have electric light or running water but Jesús left no dust on the photographs of stern ancestors on the walls of the living-room, and the nursery, if that’s what you could call one half of a partitioned bedroom, still smelled of babies, and the marble slab of the sink was scoured clean. But it was very different from Antonio’s house to the south of the Retiro which was built on three floors with two balconies.

‘Please let me in,’ Martine said. Ana hesitated but there was a hunted look about the French woman and, noting the swell of her belly, she opened the door wider.

Jesús was stirring a bubbling stew with a wooden ladle. Food was becoming scarcer as the Fascists advanced on Madrid but he always managed to provide. He greeted Martine without animosity and continued to stir.

Martine sat on a chair, upholstered in red brocade, that Jesús had found on a rubbish dump, the expensive leather of her shoes biting the flesh above her ankles.

Ana said, ‘Take them off, if you wish.’ Martine eased the shoes off, sighing. ‘So what can we poor revolutionaries do for you?’ Ana asked.

Martine spoke in fluent Spanish. Jesús should leave, she said. Ana shrugged. Everyone suspected everyone these days. She said to Jesús, ‘I hear there are some potatoes in the market; see if you can get some.’

‘Very well, querida. Take care of the stew.’ He wiped his hands on a cloth and, smiling gently, walked into the lambent sunshine.

‘He is a kind man,’ Martine said. ‘A gentle man.’

Born in the wrong time, Ana thought. ‘You never thought much of him in the past.’

‘I don’t understand politics. They are not a woman’s business.’

‘Tell that to La Pasionaria. She is our leader, our inspiration.’

‘Really? I thought Manuel Azaña was the leader.’

‘He is president,’ Ana said. ‘That is different. He is a figurehead: Dolores is our lifeblood.’ Martine leaned back in the chair. Ana noticed muddy stains beneath her eyes. ‘So what is it you want?’ she asked her.

Martine arranged her hands across her belly. She stared at Ana. Whatever was coming needed courage. When she finally spoke the words were a blizzard.