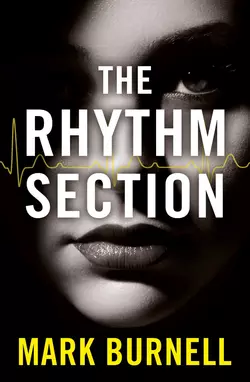

The Rhythm Section

Mark Burnell

Soon to be a major motion picture, from the producers of the James Bond film series, starring Jude Law and Blake Lively.She has nothing to lose and only revenge to live forShe thought her life was over…Stephanie Patrick's life is destroyed by the crash of flight NE027: her family was on board and there were no survivors.Devastated, she falls into a world of drugs and prostitution – until the day she discovers that the crash wasn't an accident, but an act of terrorism.Filled with rage, and with nothing left to lose, she joins a covert intelligence organization. But throughout her training and operations she remains focused on one goal above all: revenge.

THE RHYTHM SECTION

Mark Burnell

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_075da065-9873-5508-a77d-060cf71f863b)

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 1999 Copyright © Mark Burnell 1999

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780006513377

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007397556

Version: 2018-07-04

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

DEDICATION (#ulink_19921ba0-89e2-5169-aced-2212c798b0d0)

To my parents, with love and thanks for your ceaseless support.

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_c9b04da1-1348-542c-a0f6-2c36bbe8986c)

Character is destiny.

George Eliot/Mill On The Floss

Let’s make us medicine of our great revenge,

to cure this deadly grief.

William Shakespeare/Macbeth

CONTENTS

Cover (#u72587cd9-ecb8-5c84-a059-41a471122b73)

Title Page (#uaa082568-adad-5220-8aef-eed29ed0c1b8)

Copyright (#uc550b0a9-3368-5dbc-a46c-942e2bd370c3)

Dedication (#ue7772c33-da0e-5a8b-8308-e06f05b5a5b0)

Epigraph (#u3322e29b-be04-5ae5-ba75-70cc7289aea0)

Foreword (#uf572c8f0-f983-5e27-85e4-5c6cbcec2df5)

0617 GMT/0117 EST (#u8b4f05d5-1f7a-5f65-aac2-f36450640e36)

1: Lisa’s World (#u7890dd91-9eec-50f3-81cc-e9cf313dcea3)

1 (#u8f335a0a-54c2-5333-95a5-7a7eec6cac5a)

2 (#u63bb850d-826f-531b-ac03-49581314cb9b)

3 (#uf3816a7d-74fe-5df5-8320-aff851b73fb5)

4 (#u9c8002ef-edaa-5762-8a2f-dc48b2725a01)

5 (#uf8764d95-ddc7-5275-b8ab-82ebc1d74c45)

2: Stephanie’s World (#u11ccc365-a623-51b5-9020-193ff2bc9570)

6 (#u1463a290-7d6f-57c2-8a4a-77e345297bf3)

7 (#ud23cf6ff-ffa1-503c-9a4d-d2b88bdaa38a)

8 (#udc4ab67b-90ca-56cb-95bf-bca356faef23)

9 (#litres_trial_promo)

10 (#litres_trial_promo)

11 (#litres_trial_promo)

12 (#litres_trial_promo)

13 (#litres_trial_promo)

3: Petra’s World (#litres_trial_promo)

14 (#litres_trial_promo)

15 (#litres_trial_promo)

16 (#litres_trial_promo)

17 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 (#litres_trial_promo)

19 (#litres_trial_promo)

20 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 (#litres_trial_promo)

4: Marina’s World (#litres_trial_promo)

22 (#litres_trial_promo)

23 (#litres_trial_promo)

24 (#litres_trial_promo)

25 (#litres_trial_promo)

26 (#litres_trial_promo)

27 (#litres_trial_promo)

28 (#litres_trial_promo)

5: The Rhythm Section (#litres_trial_promo)

29 (#litres_trial_promo)

30 (#litres_trial_promo)

0617 GMT (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mark Burnell (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_c34ef8e9-252d-5116-8768-5a845f44efc8)

The Rhythm Section was first published in 1999 and the question I am most frequently asked about it is a variation of this: how did you know about 9/11 two years before it happened? The answer, of course, is that I didn’t. The reason I get asked this, however, is because of the similarities between the events of 11 September 2001 and the terrorist plot within the novel. Those similarities are not a coincidence. The terrorist plot in The Rhythm Section is actually closer in structure to the failed 1995 Bojinka plot than to anything that occurred on 9/11, but there is a strong connection between the two because 9/11 was born out of Bojinka.

On 26 February 1993, a Pakistani man known as Ramzi Yousef (probably born Abdul Basit Mahmoud Abdul Karim, according to the 9/11 Commission, although this is disputed), parked a hired Ryder van in the car park beneath the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York. The bomb in the back of the van was intended to collapse the North Tower into the South Tower. The device detonated, killing six people and injuring more than a thousand others, but failed to topple the North Tower. In the aftermath, Yousef evaded capture and fled the United States.

The following year, on December 11, travelling on an Italian passport, Yousef boarded Philippine Airlines PAL 434, bound for Tokyo from Manila, stopping at Cebu. During the first leg of the flight, he assembled and concealed a timer-controlled bomb with components he brought on board in Manila. He then disembarked at Cebu. The device detonated over Japan, as the aircraft cruised at 33,000 feet, blowing a hole in the floor but, crucially, failing to pierce the fuselage. Astonishingly, there was only one fatality, a Japanese businessman named Haruki Ikegami, whose body absorbed much of the force of the blast. The captain diverted to the airport at Okinawa and executed an emergency landing without further loss of life.

This attack was a successful test run for a far larger operation that would employ substantially more powerful bombs. Satisfied with his progress to that point, Yousef returned to Manila and began preparations for what became known as the Bojinka plot. His chief co-conspirator in this endeavour was Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, one of the architects of 9/11, while finance was provided by Osama bin Laden.

The Bojinka plot had three distinct phases: firstly, to assassinate Pope John Paul II; secondly, to place bombs on eleven airliners flying between South-East Asia and the United States (each flight included a stop): thirdly, to fly an aircraft into the CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia. The third phase was a reduction of a more ambitious attack that had originally included other targets, among which were the White House, the Pentagon and the World Trade Center in New York.

The Bojinka plot was scheduled for January 1995, with the first phase, the assassination of Pope John Paul II, earmarked for January 15, three days after the Pontiff’s arrival in the Philippines. However, on the evening of January 6, a fire broke out in Room 603 of the Doña Josef apartment building in Manila. Yousef had rented Room 603 and was using it as an operational base. When the Manila police raided the apartment, the plot was exposed in its entirety; the bomb-making ingredients, the plans for the assassination of the Pope, the false passports to be used on the targeted flights and a laptop detailing almost every aspect of the plan.

The Bojinka plot was over and the conspirators scattered. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, however, remained convinced of the viability of the plan. Six years later, he revisited and refined it. 9/11 was a streamlined, simplified version of the Bojinka plot where bombs were ditched in favour of making the aircraft themselves the weapons. Like so many others, I watched the attacks on the Twin Towers as they occurred, understanding instantly that I was seeing history in the making. I remember feeling distinctly uncomfortable about the link between the plot of The Rhythm Section and the Bojinka plot, even though I could not have known at the time that what I was watching was a refined version of it.

Ramzi Yousef was eventually captured in Pakistan in February 1995 and is currently serving a life sentence of 240 years with no parole at the ADX Florence supermax prison in Colorado. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was arrested in Pakistan in March 2003 and is being held at Guantanamo Bay pending trial.

All of this information is now universally available and has been for years. Much of it, though not all of it, was already in the public domain back in 1997 and 1998 when I was preparing and writing The Rhythm Section.

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, I found my opinion being sought. I remember sitting on a panel of a late-night radio talk show, surrounded by experts from the intelligence community and feeling somewhat of a fraud. There was an assumption among people I met that I had some special insight to offer, that I must have had sources or contacts within the intelligence community who had provided me with raw material for the novel. This was not the case. I never met anybody from the intelligence community until after 9/11. In some instances, my insistence upon this only appeared to strengthen their suspicion: well of course you would deny it, wouldn’t you?

Interestingly, those from the intelligence community whom I have subsequently met are often more interested in the fact that I reference Osama bin Laden in The Rhythm Section. I have always found this surprising for two reasons: firstly, bin Laden is only referenced once in the novel, and rather briefly at that; secondly, although he had yet to become a household name, bin Laden was already an established and recognised terrorist entity by 1997.

The Rhythm Section was researched and written in my own pre-internet era. As a technological late adopter, I didn’t use the internet at all during the preparation of the novel. Planning was done the old-fashioned way, collating material from books and articles. It’s a method that has served me well and which I still prefer. Although I use the internet now, I still require alternative verification for research. To mis-paraphrase a quote: ‘Google will provide you with a thousand answers. A library will provide you with the correct answer.’

I always travel to the locations in which my novels are set. Again, the internet is a useful starting point and can certainly reduce the amount of time spent scouting locations. But it cannot be a perfect substitute. Authors who are over-reliant upon on the internet run the risk of getting found out and that is a serious flaw for a thriller, where the suspension of disbelief is critical. The better the research, the more likely you will be able to take the reader with you. To remind me of this, I keep a terrible novel on a shelf in my office as a permanent warning of all the pitfalls that a thriller writer needs to strive to avoid: lack of character development, an over-reliance on plot, an overly contrived plot, any form of cliché, bad dialogue, to name but a few. This novel was a huge international bestseller and comfortably one of the worst books I have ever read. Its presence in my office, and the fact that is so awful yet sold so well, serves two purposes – firstly, as a constant reminder to be vigilant, and, secondly, to remind myself that the true taste of the public is ultimately unknowable and that the Gods that govern writing are capricious.

The Rhythm Section is written almost exclusively from the perspective of its central character, Stephanie Patrick. This was a proactive choice that was made much easier by the decision not to dwell too much on the characters of the terrorists. In almost everything I have ever read, heard or seen, it is striking how screamingly tedious most terrorists appear to be. They are voids, character replaced by incoherent rage or dogma, often spoon-fed rather than self-generated. Nothing in them is original. I see a similarity between the type of individual who becomes a suicide-bomber and the lengthening list of men who rampage through American schools armed with assault rifles. What unites them is their extraordinary solipsism. They dehumanise their victims because they lack empathy, a key marker for psychopathy. With a suicide-bomber or a school-shooter, it’s never really about the cause or the grievance. It’s about them. Hey, look at me. Please, just for a second…

Their empty lives are given relevance for a fleeting moment, although the increasing frequency of such events inevitably dilutes and diminishes even that. I wonder whether there may be a societal connection between the increase in American school slaughters and the rise of the age of the selfie. Suicide-bombers, after all, have often resorted to narcissistic pre-recorded messages which, while chilling to watch, are also pathetic and empty, generally leaving a lasting impression that they are the calling cards of the perennial loser.

Originally, the central character in The Rhythm Section was going to be male. This decision was more of a lazy default than a considered choice. Yet, looking back, I am convinced there must have always been some part of me that knew the character should be a woman. I have no recollection now of whether I ever ascribed a name to this male character. I don’t remember anything about his background. Perhaps that is the point: he was going to be central to the story whereas Stephanie is the story. Tellingly, when the central character was going to be male, I was focused on the plot. Once Stephanie assumed that role, I was focused on her and the plot evolved around her.

A lot of writing is procedure – planning, execution, revision – but occasionally one has a ‘eureka’ moment. And so it was with Stephanie. Once I committed myself to a female central character, Stephanie arrived fully formed, almost instantaneously. This I remember clearly. She came with a look, an attitude and a well-defined background. Most significantly, she had a name. I never considered other options. She was always Stephanie Patrick and that name represented to me everything that she was. Even the sound of it seemed to embody somehow the crystallisation of all that she was before The Rhythm Section begins, and of everything she then becomes.

If Stephanie’s greatest asset is her intelligence, her greatest flaw may be her temperament. She is difficult, spiky. She is prone to a quip when silence would be better. She’s got a smart mouth on her that can get her out of trouble, but no more frequently than it lands her in trouble. Academically gifted, she was rebellious at school just because…

Having played the part of the teenage rebel within the secure and nurturing environment of her family, her life is then ripped apart and, for all her superficial toughness, she is utterly incapable of dealing with it. By the time the novel starts, she is physically and emotionally ruined and, to a large degree, it’s self-inflicted.

This is a constant theme in Stephanie’s evolution; she may be appalled by her own behaviour and choices but she is no fan of self-pity. She is searingly honest about her weaknesses and the poor decisions she makes. She would love to be loved but can’t see how that could happen. Or that she deserves it. When she falls for someone she can never really do it completely: total trust is just too great a leap for her. Stephanie is a woman within whom there is a perpetual state of emotional civil war.

I am pleased to have been given the opportunity to write this introduction to The Rhythm Section since Stephanie will very soon cease to exist as a purely literary character. At the time of writing, filming is underway for a screen version of The Rhythm Section. The novel has been under option constantly since it was first published in 1999 and the wait has, at times, been very frustrating. For many years, I was convinced the film would never be made. But the team that has now been assembled to change that is so gifted that I can say, in all honesty, it’s been worth the wait. Blake Lively stars as Stephanie and her performance is just mesmerising. It has exceeded everything I had hoped for and anything I had to a right to expect.

A film is a collective effort and I would like to thank the many talented people who have worked on The Rhythm Section. Few, if any, authors have been better served by cast and crew. The public face of this film is most definitely female; producer Barbara Broccoli, director Reed Morano and Blake herself are a deeply impressive trio and it feels totally appropriate that they should bring Stephanie to the screen. She would definitely approve!

Mark Burnell, September 2018

0617 GMT/0117 EST (#ulink_01b22374-b602-5bde-951e-47daa890e665)

Outside, the temperature has reached –52°C. Inside, it’s a constant 23°C. Outside, there is speed. Inside, there is stillness. Outside, the air pressure is consistent with an altitude of thirty-seven thousand feet. Inside, the air pressure is equivalent to an altitude of six thousand five hundred feet. Made from aluminium and assembled near Seattle, the dividing line between these two mutually hostile environments is just two millimetres thick.

Martin Douglas had his eyes closed but he was not asleep. The occupant of seat 49C, a resident of Manhattan and a native of Uniondale, New York, Douglas focused on his breathing and tried to ignore the tension that was his invisible co-passenger on every flight he took. The airline’s classical music channel piped Mahler through his headphones. The music took the edge off the drone of the engines, masking the tiny changes in pitch, every one of which usually accelerated Douglas’ pulse. Now, however, with soothing music in his ears and with the fatigue that follows relentless anxiety starting to set in, he was almost relaxed. His eyelids were heavy when he half-opened them. An inflight movie was flickering on the TV screens above the aisles but most of the passengers around him were asleep. He envied them. On the far side of the cabin he noticed a couple of cones of brightness falling from reading lights embedded in the ceiling. He closed his eyes again.

When the explosion occurred, North Eastern Airlines flight NE027 was flying over the Atlantic, bound for London’s Heathrow Airport from New York’s JFK. Including flight crew and cabin crew, there were three hundred and eighty-eight people on board the twenty-six-year-old Boeing 747.

First Officer Elliot Sweitzer was drinking coffee. Larry Cooke, the engineer, was returning to his seat after a brief walk to stretch his legs. The lights on the flight deck were dimmed. Outside, it was a beautiful clear night. A brilliant moon cast silver light on to the gentle ocean below. The stars glittered above the aircraft. To the east and to the north, the sky was plum purple with a hint of bloody red along the curved horizon.

The countless hours spent in a 747 simulator combined with years of actual flying experience counted for nothing in preparing the pilots for the physical shock of the blast. Sweitzer’s coffee cup flew free of his grasp and shattered on the instruments in front of him. Cooke’s seat-belt was not properly fastened and he was hurled into the back of Sweitzer’s seat. He heard his collar-bone snap.

Instantly, the flight deck was filled with mist as the howl of decompression began. Captain Lewis Marriot reacted first. Attaching an oxygen mask to his face, he began to absorb the terrifying information that surrounded him. ‘Rapid depressurization drill!’ He turned to his co-pilot. ‘Elliot, are you all right?’

Sweitzer was fumbling with his mask. ‘Okay … I’m okay …’

‘You fly it,’ Marriot commanded him, before turning to check on Cooke. ‘Larry?’

There was blood on Cooke’s forehead. His left arm was entirely numb. He could feel the break in the collar-bone against his shirt. Gingerly, he hauled himself back into his seat and attached his own oxygen mask. ‘I’ll be … fine …’

‘Then talk to me.’

On the panel in front of Cooke the loss of cabin pressure was indicated by a red flashing light. A siren began to wail. Cooke pressed the light to silence it. ‘I got a master warning for loss of cabin pressure.’

Sweitzer said, ‘We need to get to a lower altitude.’

Marriot nodded. ‘Set flight level change. Close thrust. Activate speed brake.’

A yellow light began to flash in front of Cooke. ‘I’ve got a hydraulics master caution.’ He pressed the light to reset it. Two seconds later, it went off again. ‘We’ve lost one set of hydraulics.’ The 747–200 was fitted with three different hydraulics systems. ‘I also got a fuel imbalance warning.’ A red master warning light came on, accompanied by the ringing of a bell. ‘Fire!’

Sweitzer said, ‘The auto-pilot’s in trouble. I’m getting a vibration.’

Marriot looked at Cooke. ‘Engine fire check list. What’s it on?’

‘Two.’

Under Cooke’s supervision, Marriot closed the number two engine, shut off the fuel control switch, and then pulled the number two fire handle to close the hydraulics and fuel valves. Then he twisted the handle to activate the fire extinguishers.

‘We’re losing the auto-pilot. The second set of hydraulics is going.’

‘Deactivate the auto-pilot, Elliot.’

Sweitzer nodded. ‘We’re going to have to slow her down. There’s too much vibration.’

‘Just keep her steady and make the turn. We’re heading for Gander.’

Gander, in Newfoundland, was the closest runway to them.

Sweitzer was struggling with the control column. ‘God, she’s sluggish!’

The fire bell sounded again in conjunction with a master warning light. Cooke said, ‘We need the second shot with the fire extinguisher. It’s still burning.’

‘I think we’ve got a rudder problem and maybe a jammed stabilizer. The trim’s shot to hell.’

Marriot turned the radio to VHF 1215, the emergency frequency. ‘Mayday, Mayday, Mayday! This is North Eastern Zero Two Seven. We are in emergency descent. We have structural damage. We have an engine fire, not extinguished.’

The violent deceleration hurled everyone forwards. Those whose seat-belts were unfastened were ejected from their seats. Martin Douglas was lifted from his but the belt cut across the top of his thighs and restrained him. His head hit the seat in front. The blow knocked him senseless and his body was immediately snapped back against his own seat.

He was only unconscious for three seconds. Despite being dazed, Douglas knew that his nose was broken. The back of the seat in front had crushed it and ripped the skin in several directions. Blood was seeping from the star-shaped gash but it was not slithering down his face. It was not staining his shirt or splattering his lap. Instead, it was being sucked off his skin. A sticky stream of crimson drops was hurtling forwards, flying over the seats in front, borne on the rushing air.

Further forward, part of the cabin floor had collapsed. Broken seats were wrenched from their moorings and sucked into the night. A tornado tore through the fuselage, ripping clothes from bodies, bodies from seats, hand-luggage from floors and overhead lockers. All of this debris was inhaled by some enormous invisible force towards the front of the 747. The majority of those who could were screaming, but their pitiful shrieks were lost in the roar of decompression. Others were unconscious. Or already dead.

The pain in his ears was agonizing, a consequence of the colossal percussive clap and the violent change in air pressure. But compared to the fear, his pain was a minor irritation. The terror constricted his throat, his stomach, his chest. As the aircraft began to descend, Douglas instinctively pushed against the arm-rests, raising himself upwards, stretching himself, as if to counteract, in whatever minuscule way possible, the 747’s descent. The entire aircraft was vibrating uncontrollably. To Douglas, it seemed that this was Hell and that whatever was to follow could be no worse.

The boy who had been asleep in seat 49B was no longer there. His belt had been fastened but not securely enough. The girl by the window was either unconscious or dead. Her hair was drawn forwards, masking her face, but there was a thick smudge of her blood on the window’s blind. It looked black.

Oxygen masks fell from the ceiling and were drawn towards the source of depressurization. Douglas reached for one, retrieved it by the plastic tube and yanked it towards him, placing it over his nose and mouth. Breathing through the mask proved to be harder than fixing it to his face; his lungs seemed to be shutting down, each breath becoming shallower than the one before, the time between them shrinking. Small white stars were exploding in his eyes.

He allowed himself to look around. It was dark in the cabin but of those he could see, he was one of the few who was still conscious. Even as a nervous flyer, he had never imagined that any fear could be so acute, that his worst nightmare made real would be quite so surgical in the way that it sliced him apart.

The fire bell sounded again. Cooke didn’t know where to start. Every light was ablaze. He guessed – because he didn’t want to admit to himself that he knew – that the fire, which was still raging, was burning through the third and last of their hydraulics systems. The aircraft’s descent was transforming into a plunge.

He gripped Marriot’s shoulder. ‘The fire’s spreading. You better make the call.’

Marriot checked the 1215 frequency. ‘Mayday, Mayday, Mayday! This is North Eastern Zero Two Seven. We are in emergency descent. We are going down. We have an uncontrolled fire on board. We have a complete hydraulics failure. We cannot complete our turn for Gander. This is our last call. Our position is fifty-four north, forty west. We will try to –’

Martin Douglas was on the verge of hyperventilating, a condition that would have been welcome. To pass out would have been a merciful relief. There was smoke in the cabin.

He had been in a car crash once. Travelling at over seventy miles an hour on a road that cut through a forest in Vermont, he had hit a patch of black ice. His car had skidded sideways and veered on to the wrong side of the road. Fortunately, there had been no oncoming traffic. Unfortunately, there had been pine trees lining the road. He’d had time to think, then – a few moments to anticipate the collision, to feel fear, to contemplate death as a serious possibility. This was different. Death was not a serious possibility. It was an inevitability. The aircraft was falling like a rock. Essentially, he knew that he was already dead.

When his breathing could become no shallower or quicker, he stopped. For a second. And then took a deep breath. With it, the accumulated tension flooded out of him. He felt it drain from his head, through his chest and stomach, down his legs and out through the soles of his feet and into the frame of the disintegrating 747.

And for one moment in his life, Martin Douglas was at peace inside an aircraft.

1 LISA’S WORLD (#ulink_f4d3177c-0d1c-5dc5-92c4-fd3ae652bd34)

1 (#ulink_c075e252-8fa0-5c7f-b065-94f48ee4b428)

She’s a chemical blonde.

The carder was a stout skinhead in a Reebok track-suit who carried a canvas satchel stuffed with prostitutes’ advertising cards. Along Baker Street, he moved from phone-box to phone-box, sticking the cards to the glass with Blu-Tack. Keith Proctor watched him from a distance before approaching him. He showed him the scrap of card he’d been given by one of her friends and asked the man if he knew who she was. It cost fifty pounds to persuade the carder to talk. Yes, he knew who she was. No, she wasn’t one of his. He’d heard a rumour she was working in Soho.

On the fragment of dirty yellow card there was a photograph of a woman offering her breasts, plumping them between her hands. The bottom half of the card – the half with the phone number – was missing.

An hour later, Proctor hurried along Shaftesbury Avenue. The falling drizzle was so fine it hung in the air like mist but its wetness penetrated everything. Those who were heading across Cambridge Circus towards the Palace Theatre for the evening’s performance of Les Misérables looked suitably miserable, shoulders curved and heads bowed against the damp chill. The traffic on the Charing Cross Road was solid. Red tail lights shivered in puddles.

There was a cluster of four old-fashioned phone-boxes on Cambridge Circus. Proctor waited for five minutes for one of them to become free. As the heavy door swung behind him, muting the sound outside, he realized someone had been smoking in the phone-box. The smell of stale cigarettes was unpleasant but Proctor found himself grudgingly grateful for it since it mostly masked the underlying stench of urine.

Three sides of the phone-box were covered by prostitutes’ advertising cards. Proctor let his eyes roam over the selection. Some were photos, in colour or black and white, others were drawings. Some merely contained text, usually printed although, in a few cases, they had been scrawled by hand. They offered straight sex, oral sex, anal sex. They were redheads, blondes and brunettes. They were older women and they were teenagers. To the top of the phone-box, they were stacked like goods on a supermarket shelf. Black, Asian, Oriental, Scandinavian, Proctor saw specific nationalities singled out; ‘busty Dutch girl – only 21’, ‘Brazilian transsexual – new in town’, ‘Aussie babe for fun and games’, ‘German nymphomaniac, 19 – nothing refused’. One card proclaimed: ‘Mature woman – and proud of it! Forty-four’s not just my chest size – it’s my age!’

Proctor took the torn yellow card out of his pocket and scanned those in the phone-box. He made a match high to his left. The one on the wall was complete, the phone number running along the bottom half. He forced a twenty-pence piece into the slot and dialled.

A woman answered, her voice more weary than seductive.

‘I … I’m in a phone-box,’ Proctor stammered. ‘On … on Cambridge Circus.’

‘We’re in Brewer Street. Do you know it?’

‘Yes.’

‘The girl we’ve got on today is a real stunner. She’s called Lisa and she’s a blonde with a gorgeous figure and lovely long legs. She’s a genuine eighteen-year-old and her measurements are …’

Proctor felt deadened by the pitch.

‘It’s thirty pounds for a massage with hand-relief and her prices go up to eighty pounds for the full personal service. What was it you were looking for, darling?’

He had no answer at the ready. ‘I … I’m not sure …’

‘Well, why don’t you discuss it with the young lady in person?’

‘What?’

‘You can decide when you get here. When were you thinking of coming round?’

‘I don’t know. When would be …?’

‘She’s free now.’ Like a door-to-door salesman, she gave Proctor no time to think. ‘It’ll only take you five minutes to get here. Do you want the address?’

There were Christmas decorations draped across the roads and hanging from street lamps. They filled the windows of pubs and restaurants. Their crass brightness matched the gaudy lights of the sex shops. Proctor passed a young homeless couple, who were huddling in a shallow doorway, trying to keep dry, if not warm. They were sharing a can of Special Brew.

The address was opposite the Raymond Revuebar, between an Asian mini-market and a store peddling pornographic videos. The woman answered the intercom. ‘Top of the stairs.’

The hall was cramped and poorly lit. Broken bicycles and discarded furniture had been stored beneath the fragile staircase. Proctor felt a tightness in his stomach as he started to climb the stairs. On each landing there were either two or three front doors. None of them matched. Most were dilapidated, their hinges barely clinging to their rotting frames, rendering their locks redundant. On the third floor, though, he passed a new door. It was painted black and it was clear that a whole section of wall had been removed and rebuilt to accommodate it. It had three, gleaming, heavy-duty steel locks.

The door at the top of the staircase was held open by an obese woman in her fifties with tinted glasses. She wore Nike trainers, a pair of stretched grey leggings and a violet jersey, sleeves rolled up to the elbows. The flat was a converted attic. In a small sitting room, a large television dominated. On a broken beige sofa there was an open pizza carton; half the pizza was still in it. The woman steered Proctor into the room at the end.

‘You want something to drink, darling?’

‘No.’

‘All right, then. You wait here. She’ll be with you in a minute.’

She closed the door and Proctor was alone. There was a king-sized mattress on a low wooden frame. The bed-cover was dark green. On the mantelpiece, on the table in the far corner and on the two boxes that passed for bedside tables, there were old bottles of wine with candles protruding from their necks. On top of a chest of drawers there was a blue glass bowl with several dozen condoms in it. The room was hot and reeked of baby oil and cigarettes. Proctor walked over to the window, the naked floorboards creaking beneath his feet. Pulsing lights from the street tinted curtains so flimsy that he could almost see through them. He parted them and looked down upon the congested road below.

‘Looking for someone?’

He hadn’t heard her open the door. He turned round. She wore a crimson satin gown and when she turned to close the door, Proctor noticed a large dragon running down the back of it. The gown was open and beneath it, she wore black underwear, a suspender-belt and a pair of high-heeled shoes. Her hair was blonde – chemically blonde – but her dark roots were showing. It was shoulder-length and, even in the relative gloom, looked as though it could have been cleaner.

No trick of the light, however, could disguise her paleness, her thinness or her weariness. She had a frame for a fuller figure but she didn’t have the flesh for it. When she moved, her open gown parted further and, from across the room, Proctor could see her ribs corrugating her skin. Her face was made-up – peach cheeks, bloody lips and heavy eye-liner – but the rest of her body was utterly white, and when she smiled she only succeeded in looking tired. ‘My name’s Lisa. What’s yours?’

He ignored the question. ‘You don’t look like you do on the card.’

She shrugged. ‘I don’t want to be walking down the street seeing myself in every phone-box I pass. And I don’t want people pointing at me because they’ve recognized me from my picture, do I?’

‘I guess not.’

She kept her distance and put a hand on her hip, revealing a little more of herself. ‘So, what do you want?’

Proctor’s hand was in his coat pocket. He felt the torn yellow card. ‘I just want to talk.’

Her cheap smile faded. ‘I don’t charge less than thirty for anything. And for that, you get a massage and hand-relief.’

‘What’s your name?’

‘I told you. Lisa.’

‘Is that your real name?’

‘Maybe.’

‘Is that a yes or a no?’

‘What’s it to you?’

‘I’d just like to know, that’s all.’

She paused for a moment. ‘Tell you what, why don’t you tell me? Who do you think I am? Lisa, or someone else?’

‘I think you’re someone else.’

‘Really?’ She smiled again but it failed to soften the hardness in her gaze. ‘Who?’

‘I think your real name might be … Stephanie.’ Not even a flinch. Proctor was disappointed. ‘Are you Stephanie?’

‘That depends.’

‘On what?’

‘On your money. If I don’t see some, I’m nobody. If you just want to talk, that’s fine but it’ll still cost you thirty. I don’t do anything for free.’

Proctor reached for his wallet. ‘Thirty?’

She nodded. ‘Thirty. And for thirty, I’ll be Stephanie, or Lisa, or whoever you want.’

Proctor held three tens just out of her grasp. ‘Will you be yourself?’

She said nothing until he handed her the notes. And then, as she was folding them in half, she asked, ‘What are you doing here? What do you really want?’

‘The truth.’

‘I’m a prostitute, not a priest. There’s no truth here. Not from me, not from you.’ When Proctor frowned at this, she added: ‘When you get home this evening, are you going to tell your wife you went to see a hooker? That you paid her money?’

‘I’m not married.’

‘Your girlfriend, then. Anyone …’ Proctor didn’t need to say anything. ‘I thought not. So don’t come here and talk to me about the truth.’

Not only was her tone changing, so was her accent; south London was being displaced by something less readily identifiable. Just as her opening remarks had been laced with a dose of sleazy tease, now she was cold and direct.

Proctor was equally blunt. ‘I think your real name is Stephanie Patrick.’

This time, he knew he was right. The surname betrayed her and she froze, if only for a fraction of a second. He saw her try to shrug it off but he also saw that she knew he’d seen it.

‘I’m right, aren’t I?’

For the first time, she looked openly hostile. ‘Who are you?’

‘Your name is Stephanie Patrick, isn’t it?’

She looked down at the money in her fist and said, ‘Let me give this to the maid and then we’ll talk. Okay?’

It took Proctor a couple of seconds to realize that the ‘maid’ was the fat woman who had admitted him to the flat. ‘Okay.’

Lisa – for that was who she still seemed to be – turned away and left him alone in the room. When she returned, a couple of minutes later, she had transformed into a man who was six-foot-four and built like a weight-lifter. He had no neck, his huge shaven head merging with the grotesque bulges of his shoulder muscles. His white T-shirt was so tight it could have been body-paint.

He didn’t need to raise his voice when he pointed at Proctor and murmured, ‘You. Outside. Now.’

Proctor rolled over, vaguely aware of the soggy rubbish that was squashed beneath his body. The drizzle fell softly on to his stinging face. One eye was closing. Through the other, he saw two walls of blackened brick converging as they rose. He was in an alley of some sort and it stank.

The beating had been short, brutal and depressingly efficient; the administrator was clearly no novice. After a final kick to the ribs, he’d hissed a blunt warning: ‘If I ever see you here again, I’ll tear your fucking balls off. And that’s just for starters. Now piss off out of here.’

With that, a door had slammed shut and Proctor had been by himself, lying on a bed of rotting rubbish. For a while, he made no attempt to move. He lay on his back, his arms wrapped around his burning ribs. He tasted blood in his mouth.

He looked up and saw smudges of buttery light seeping from cracks in drawn curtains. And from a partially-opened window, he heard Bing Crosby crooning on a radio.

I’m dreaming of a White Christmas …

2 (#ulink_7519f8a0-d20e-5d9d-bc89-6db6e4503cac)

Proctor saw her before she saw him. He was standing in a restaurant doorway, trying to keep dry. The drizzle of the previous night had matured into real rain. When he glimpsed her, she was heading his way, so he retreated from view. Inside the restaurant, staff were preparing for lunch, placing tall wine glasses and small dishes of chilled butter on tables draped in starched white cloth.

He waited until she was close. ‘Lisa?’

She stopped but it took a moment for her to recognize him beneath his mask of bruises. Proctor raised his hands in surrender. ‘I don’t want any trouble. I just want to talk.’

She looked as though she would run. ‘Leave me alone,’ she hissed.

‘Please. It’s important.’

He saw the hardness in her gaze again. ‘Which part don’t you understand? Or maybe you just enjoy getting your head kicked in.’

‘No, I don’t. That’s why I waited for you here and not in Brewer Street.’

‘How’d you know I’d come this way?’

He shrugged. ‘I didn’t. But I guessed you didn’t live there so you’d be coming from somewhere else. And then I guessed you’d come on the Underground, not a bus. And since this is on the shortest route between the nearest station and Brewer Street …’

‘Smart,’ she said, flatly. ‘But I could’ve come another way. I often do.’

‘You could’ve. But you didn’t.’

According to Proctor’s information, Stephanie Patrick was twenty-two. The woman in front of him looked at least ten years older than that. Her dyed blonde hair was dishevelled and with her make-up removed, her face was as colourless as the rest of her. Except for the dark smudges around both eyes. But now, in the morning, they were natural, not cosmetic.

She wore a tatty, black, leather bomber-jacket over a grey sweatshirt. Her jeans were frayed at the knees and down the thighs; given the weather, this seemed more like a financial statement than one of fashion. Her blue canvas trainers were soaked.

‘How long have you been here?’ she asked him.

‘Since nine-thirty.’

She glanced at her plastic watch. It was after eleven. ‘You must be cold.’

‘And wet. And in pain.’

He saw a hint of a smile.

‘I can imagine. He’s not known for his subtlety. Just for his thoroughness.’ She examined Proctor’s face. ‘You look like shit.’

Proctor hadn’t slept. When the paracetamol had failed, he’d resorted to alcoholic painkiller, which had also failed. And not being a seasoned drinker, the experience had left him with a hangover to compound his misery. His body was peppered with bruises, his left eye was badly swollen, his ribs ached with every breath and his right ankle, which had been twisted on the stairs, was aflame.

‘Look, if you’re not going to talk to me, fine. But let me ask you one question. Are you or are you not Stephanie Patrick, daughter of Dr Andrew Patrick and Monica Patrick?’

He needed to hear the answer that he already knew. She took her time.

‘First, who are you?’

‘My name is Keith Proctor.’

‘Why are you asking me these things?’

‘It’s part of my job.’

‘Which is what?’

‘I’m a journalist.’ Predictably, she grew yet more defensive, her posture betraying her silence. Proctor said, ‘Your parents were on the North Eastern Airlines flight that crashed into the Atlantic two years ago. So were your sister and your younger brother.’

He watched her run through the phrases in her mind before she chose one. ‘I’ve got nothing to say to you. Leave me alone. Leave it alone.’

‘Believe me, I’d like to. But I can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because it wasn’t an accident.’

The bait was cast and she considered it for a moment. Before ignoring it. ‘I don’t believe you.’

‘I don’t expect you to. Not yet. Not until you’ve given me a chance.’ She shook her head but Proctor persisted. ‘I need a cup of coffee, Miss Patrick. Will you let me buy you one, too? I’ll pay for your time.’

‘People pay me for my body, not my time.’

‘They pay for both. Come on. Just one cup of coffee.’

Bar Bruno, on the corner of Wardour Street and Peter Street, was half-full. It offered fried breakfasts all day. There was a large Coke vending machine just inside the door. Behind a long glass counter, sandwich fillings were displayed in dishes. The table-tops looked like wood but weren’t. The banquettes were covered in shiny green plastic.

They ordered coffee and sat at the back where there were fewer people. Stephanie wriggled out of her leather jacket and dumped it beside her. Proctor’s eyes were immediately drawn to her wrists. Both were seriously bruised. She looked as if she was wearing purple handcuffs. They hadn’t been there the previous night; he was sure he would have noticed. She saw him looking at them.

‘What happened?’ he asked.

‘Nothing,’ she snapped.

‘It doesn’t look like nothing.’

‘You’re a fine one to talk. Have you looked in a mirror this morning?’

‘Unfortunately, yes.’

Momentarily angry, she thrust both wrists in front of Proctor’s face for closer inspection. ‘You want to know what this is? It’s an occasional occupational hazard, that’s what it is.’ Then she was calm and stirring sugar into her milky coffee, before changing the subject. ‘Have you got any cigarettes on you?’

‘I don’t smoke.’

‘I didn’t think so, but you never know until you ask.’ Proctor watched her produce a packet of her own from her jacket pocket. She lit one and dropped the dead match on her saucer. ‘So, you’re a journalist.’

‘Yes.’

‘You don’t look like one.’

‘I didn’t realize there was a look.’

‘I’m not saying there is. I’m talking about the way you look. Good haircut, nice suit, expensive shoes and clear skin – apart from the bruises, of course. You look like you take care of yourself.’

‘I try to.’

‘Who do you work for?’

‘I’m freelance. But I used to work for The Independent and then the Financial Times.’

‘Impressive.’

‘Not to you, I shouldn’t think.’

Stephanie took a sip of coffee. ‘You haven’t a clue what I think.’

More than anything, she looked nervous, despite the aggression in her small talk. She fidgeted incessantly and her eyes never settled on anything. Proctor took a sip of his own coffee and grimaced.

‘Your parents were murdered,’ he said for effect. She seemed oblivious, as though she hadn’t even heard him. ‘Along with everyone else on that flight.’

‘That’s not true. There was an investigation –’

‘Faulty electrics in the belly of the aircraft which produced a spark igniting aviation fuel fumes, causing the first of two catastrophic explosions? I read the FAA and CAA findings like everyone else. And until recently, I believed them. Everyone believed them. And, as a consequence of that, some of the electrical systems on some of the older 747s were changed. Problem addressed, problem solved. Except it wasn’t. The problem’s still out there, walking around with a pulse, a brain and a name.’

Her look said it all. You’re either crazy or you’re stupid. Proctor leaned forward and lowered his voice. ‘It was a bomb that destroyed that aircraft. It wasn’t an accident.’

He waited for the reaction; a gasp of shock, or a denial, or something else. Instead, he got nothing. Stephanie picked at her fingernails and he noticed how dirty they were. And cracked. Her fingertips looked raw.

‘How much money have you got on you?’ she asked.

‘What?’

‘Cash. How much have you got on you?’

‘I don’t know.’

She looked up to meet his eyes. ‘I need money and you said you’d pay me.’

Proctor was at sea. ‘Look, I’m trying to explain to you –’

‘I know. But I need this money now.’

‘Aren’t you interested?’

‘Are you going to give it to me or not? Because if you’re not, I’m leaving.’

‘I paid you thirty last night and look what it bought me.’

She stood up and picked up her jacket.

To buy himself time, Proctor reached for his wallet again. ‘There was a bomb on that flight. The authorities know this but they’re keeping it secret.’

Stephanie sounded bored. ‘You reckon?’

‘They even know who planted it.’

‘Right.’ Her eyes were on the wallet.

‘He’s alive and he’s here, in London. But they’re making no attempt to apprehend him.’

She held out her hand. ‘Whatever you say.’

Proctor gave her two twenties. ‘I don’t get it. This is your family we’re talking about, not mine.’

‘Forty? I need a hundred. Seventy-five, at least.’

Proctor gave a cough of bitter laughter. ‘For what? Your time? Do me a favour …’

‘Bastard.’

He reached across the table and grabbed a purple wrist. She winced but he didn’t loosen his grip. With his other hand, he pressed a business card on to the two twenties and then closed her cold fingers over it. ‘Why don’t you go home and think about it, and then give me a call?’

She stared him down with a face as full of hatred as any he had ever seen. ‘Let go of me.’

I am difficult. I always have been and I always will be. I’m not proud of it but I’m not ashamed of it, either. It’s just the way I am, it’s my nature. In the past, I was aggressively difficult – sometimes out of pure malice – but these days, I would say that I am difficult in a more defensive way. It’s a form of protection.

Proctor was wrong when he accused me of not listening. I listen to everything. I just don’t absorb much. I am like a stone; a product of molten heat turned cold and hard. Yes, we were talking about my family. But the four that are dead cannot be retrieved – nor, for that matter, can the one that still lives – and that is all there is to it.

So as I walk along Wardour Street leaving Bar Bruno behind me, I don’t think about Keith Proctor. I am not interested in his conspiracy theories. I think about the hours ahead and those who will come to see me. The regulars and the strangers. And the one who left these bands of bruising around both my wrists last night. I doubt a man like Proctor could understand how I accept that and then return the following day to run the risk of receiving the sametreatment. Or something even worse. The truth is, it’s not so hard. Not any more. I live alone inside a fortress of my own construction. Physical pain means nothing to me.

I am sure there are analysts out there who would enjoy studying me. Of course, they would be frustrated by me since I would refuse to speak to them. Nobody is allowed inside. That is how I survive. I am two different people; the protected, vulnerable soul within the walls and the indestructible, empty soul on the outside. When I am on track, this is how I live; but when I am derailed, it’s a different story.

It’s not easy being two different people at once. The pressure never ceases. Unless you have experienced it, you cannot know. So sometimes, when the borders blur, I fall apart. When I am cold and hard, I have to be in total control of myself – even in the worst situations. If I lose the slightest fraction of that control, I effectively lose it all. And then I crash. Spectacularly. Alcohol and narcotics are what I resort to in my pursuit of utter oblivion. When I come round from one bout of drinking or drug-taking, I immediately embark upon the next. It’s critical that I allow no time for sober thought because it’s during these prolonged lows that I see myself as others see me. Then the guilt, the shame and the self-disgust set in. In these moments, the hatred I feel for myself is too much to bear and it scares me to consider the options. So I’ll ignore the taste of vomit in my mouth and reach for the vodka bottle again. And I’ll keep going until I wake up and find the phase has passed and that I am as hard as stone once more.

Those analysts would probably say that my situation is, in part, a consequence of circumstance. And, in part, they might be right. But the greater truth is this: my situation is a product of choice. I chose this life. I could have had any life I wanted. I’m certainly intelligent enough. In fact, immodest as it sounds, I can’t remember the last time I encountered an intellectual equal. Most of the time, though, I pretend I’m stupid so as to avoid unnecessary trouble; in this business, nobody likes a smart mouth. They prefer a willing mouth.

So, of all the options available to me two years ago, this is the one I chose, which begs the obvious question: why? And the honest answer is, I don’t remember any more.

3 (#ulink_72ae2a28-2399-5e79-961e-662a9ce178f0)

It was the smoker’s cough that woke her, a ghastly rib-rattling hack that repeated itself for the first hour of every morning. Stephanie was glad that it wasn’t hers. Then she remembered that it belonged to Steve Mitchell, Anne’s husband, and this reminded her of where she was. On their sofa, in their cramped sitting room.

Headswim brought on a wave of nausea. She swallowed. Her throat was dry, her skull ached, her nose was blocked. Anne and Steve were arguing in their bedroom, shouting between the coughs. The radio was on, loud enough to compete with them. Stephanie tried to ignore the noise and the smell of burned toast. How many consecutive hangovers was this? How long was it since Keith Proctor had bought her coffee? Four days? Five?

She struggled to her feet and tiptoed to the window. The Denton Estate in Chalk Farm, on the corner of Prince of Wales Road and Malden Crescent, had one high-rise building with several smaller buildings crawling around its ankles. It was a cheerless place, an ugly marriage of vertical and horizontal construction, in possession of one saving grace. The high-rise, where Steve and Anne Mitchell had their small eighth-floor flat, was a grim tower of red brick, but the view to the south was spectacular, worthy of any Park Lane penthouse. Stephanie absorbed it slowly, panning over Primrose Hill, Regent’s Park, Telecom Tower and the city beyond.

She went to the bathroom and locked herself in. She sat on the edge of the avocado bath, clutching the sink, wondering whether she was going to throw up. Last night, there had been gin, then some hideous fluid that passed for wine – possibly Turkish – before other drinks, the quantities and identities of which were now a mystery. She had no recollection of returning to Chalk Farm. But she did remember the foreign businessmen at the hotel in King’s Cross and how they had plied her with alcohol and yapped at her in a language that made no sense. With their droopy moustaches, their hairy backs, their potbellies, their gold medallions and their cheap polyester suits, they offered no surprises. Stephanie was regrettably familiar with the type.

At least it had only been alcohol. On the night after her second encounter with Proctor, she’d gone to see Barry Green and traded Proctor’s money for heroin. She’d asked Green to inject it into her – a service he sometimes provided for his regular customers – but he’d refused.

‘No punter likes to shag a slag with puncture points in her arm.’

‘What do you care?’

‘Plenty, as it happens. I don’t want to have to explain to Dean West why I put one of his girls out of action.’

‘I don’t belong to Dean West. I don’t belong to anybody.’

Green always found it hard to deny those who waved cash at him and so Stephanie got her heroin, smoking it instead of injecting it. As she had anticipated – indeed, as she secretly demanded – it was too much for her system; she threw up and passed out. When she came round, she was on a stained, damp mattress in a dimly lit store-room on the premises adjacent to Green’s ticketing agency. She was surrounded by cans of chopped tomatoes, bags of rice, drums of vegetable oil. She smelt the vomit on her jacket and the stench made her retch.

Green was standing over her. ‘That’s the last time, Steph, you got that? Any more and you’re gonna develop a habit. Are you listening to me?’ He bent down and slapped her face three times before wiping her saliva off the palm of his hand on to her leg. ‘You already do enough damage to yourself. You don’t need this.’

‘You’re right,’ she’d croaked. ‘I don’t need any of this.’

Anne Mitchell made Stephanie another cup of coffee. There was barely room for both of them in the kitchen. They sat at the small table, a tower of dirty plates between them; on the top one, tomato sauce had hardened to a crust. The gas boiler on the wall grumbled intermittently.

‘Steph, we need to talk.’

Stephanie had sensed this moment coming since Steve had gone to work. He was a plumber, which seemed unfortunately ironic considering his numerous infidelities. Whether Anne was fully aware of the extent to which he was unfaithful was unclear to Stephanie, but she knew he cheated on her and that she tolerated it because it was better than the alternative. Anne had been a prostitute when Stephanie first came to London and believed, for no good reason, that without Steve she was destined to become one again. He was still ignorant of her history and, in her mind, Anne had convinced herself that his infidelity was the price she should pay for concealing her past from him.

‘It’s Steve,’ she said, staring into her mug.

‘That’s what it sounded like.’

‘I’m sorry. Did you hear?’

‘Just the volume. Not the content.’

Anne had been pretty once; fine-featured with strawberry-blonde hair and freckles on her cheeks. Ten years ago, her regular clients had taken her away for weekends and bought her gifts. But when Stephanie had first met her, just two years ago, and shortly before she met Steve, she was selling herself cheaply and indiscriminately, and still not making enough. Now, she just looked exhausted, fifteen years older than she really was, suffering from too little sleep and too much worry.

‘You said a night, maybe two. It’s almost a week now and –’

‘It’s okay.’

Anne scratched a sore on her forearm. ‘If it was up to me, you could stay as long as you like. But you know how he is.’

Stephanie knew exactly how he was. Steve might not have known she was a prostitute but he regarded her as one, or as something equally deserving of his contempt. He never overlooked an opportunity to grope Stephanie, or to press himself against her. On one occasion, when she’d been in the bathroom, he’d barged in and locked the door behind him. Anne had been asleep on the other side of the flimsy partition wall, which was why he’d whispered his instruction to Stephanie, as he dropped his trousers: ‘On your knees.’

Similarly, she’d whispered her reply. ‘You put that anywhere near my mouth and you’re going to end up with a dick so short you’ll need a bionic eye to find it. Now put it away and get out.’

Since that incident, Steve had been increasingly hostile towards Stephanie. Consequently, her visits to Chalk Farm had become less frequent. Stephanie never stayed anywhere for long. It was nine months since she’d paid rent for a room of her own, in a flat for five that was home to eleven. Since then, she had rotated from one sofa to the next, stretching the charity of her ever-decreasing number of friends on each occasion.

‘How long have I got?’

‘You can stay tonight.’

Anne’s expression suggested that it would be better for her if Stephanie didn’t.

Stephanie sat in the last carriage, where a bored guard amused himself by hanging his head out of the door every time the train pulled away from the platform, reeling it in just before the tunnel. The Northern Line was running slow. It took half an hour to get to Leicester Square from Chalk Farm.

Stephanie preferred Soho in the morning, when it was quieter, when street-cleaners and dustmen were the ones who congested the pavements, not tourists and drunks. She stopped for a cup of coffee in a café and recognized three prostitutes at a table. None of them appeared to recognize her. She sat at the counter with her back to them. In her experience, friendships and solidarity were scarce among prostitutes. In a world mostly populated by transients, one hooker’s client was another’s missed opportunity, so there was little room for sentiment.

She overheard their conversation. They were talking about a Swedish hooker who had been gang-raped after stripping at a drunken stag night. Stephanie had recognized one of the girls at the table in particular. She called herself Claire. She was a seventeen-year-old from Chester, or Hereford, or Carlisle, or any one of a hundred other English towns that offered total disenchantment to the teenagers who grew up in them. Claire had come to London at fourteen and had been selling herself ever since. The previous year, she had spent three months in hospital after a drunken vacuum-cleaner salesman from Liverpool had beaten her to a pulp and left her for dead in a sleazy hotel off Oxford Street. She had deep, livid scars around her eyes and Stephanie knew that the reason she grew her hair long was to disguise the burns her attacker had left at the nape of her neck.

They were commenting on the Swede’s injuries with the indifference of accountants discussing tax rebate. Claire was as outwardly unmoved as the other two. As unpleasant as the facts were, they were not uncommon; if you were on the game long enough, you were bound to encounter violence. Stephanie was no exception. It was a risk run daily, a risk run hourly.

When working, Stephanie usually arrived in the West End during the late morning, from wherever she had spent the night, and then killed a few hours before being ‘on-call’. Most often, she watched TV with Joan, her ‘maid’. They drank coffee, smoked cigarettes and read the tabloids. At some point, she might eat – this was usually the only period of the day that Stephanie considered food – rolling all her meals into one. Sometimes she went to McDonald’s or Burger King, or sometimes she bought tourist fodder; grease-laden fish and chips or huge, triangular slices of pizza with lukewarm synthetic toppings and bases like damp cardboard. On other days, she visited the few friends she had made in the area; a nearby Bangladeshi newsagent, a Japanese girl from Osaka named Aki, or Clive, a diminutive Glaswegian who had a stall in the Berwick Street market and who allowed her to take a free piece of fruit from him each time she passed. When her mood was wrong, she drank before work, most often at the Coach and Horses, or else at The Ship.

As a rule, the later the hour, the rougher the trade so, given a choice, Stephanie preferred to stop working by ten. Generally, however, she found herself working later than that. And whatever the final hour, she was exhausted when it was over, even on a quiet night. Even on a blank night. Staying emotionally frozen bled all her mental stamina.

Stephanie drained her cup, left the three girls in the café – they were still discussing the attack on the unfortunate Swede – and walked to Brewer Street. She climbed the stairs and noticed that the reinforced door on the third-floor landing was open. A familiar voice came from within.

‘In here, Steph.’

Dean West. She felt her body tense and took a moment to compose herself before entering. West was drinking from a can of Red Bull. He wore a burgundy leather coat, a black polo-neck, black jeans and a pair of Doc Martens. As usual, Stephanie found her own eyes drawn to his eyes, which bulged out of his head like a frog’s, and to his teeth, which were a disaster. His mouth was too small for them; a dental crowd in an oral crush, a collage of chipped yellow chaos.

‘How was last night? Some hotel in King’s Cross, right?’

She nodded. ‘But there were two of them when I got there. Bulgarians, I think. Or Romanians.’

‘So? Twice the money.’

‘They wouldn’t pay twice.’

‘What?’

‘They didn’t speak English. They thought they’d already paid for both of them.’

‘I don’t care what they fucking thought. Money up front. That’s the rule. Always.’

‘Not this time.’

His anger deepening, West’s brow furrowed. ‘What the fuck’s wrong with you? We used to get on, you and me. I thought you was smarter than the others but now I ain’t so sure. What was the one thing I always said? Money up front! How many times d’you have to be told?’

‘I got the money up front.’ Stephanie handed West his cut. ‘For one.’

He began to count it. ‘Ain’t my fault you didn’t collect right. I want my piece of the second. And before you start, I don’t care if it comes out of your cut.’

‘They were both drunk when I arrived. They wanted me drunk too. Given the mood they were in, I thought it was best to go along with them. So I did everything they wanted and then I drank them under the table. That was when I lifted these.’ Stephanie produced two wallets from her pocket and tossed them to West. ‘You can take your cut for the second one out of there.’

West’s bloodless lips stretched into a smile as he examined the wallets. ‘Credit cards? Diners, Visa and Mastercard. Nice. What’ve we got in the other one? Visa and Amex Gold. Very tasty. Barry’ll be well chuffed.’ Barry Green, occasional vendor of drugs to Stephanie, also had a line in reprocessing credit cards, using a Korean machine that altered PIN codes on the magnetic strips. West’s good humour vanished as quickly as it had materialized. ‘But only sixty quid in cash? How much are you charging these days, Steph?’

‘The usual.’

‘And after that they only had sixty quid between them?’

‘I wouldn’t know. I haven’t counted it.’

‘Bollocks. You’ve trousered a little for yourself, ain’t you?’

A total of three hundred and fifty-five pounds. All she’d left them with were their coins. ‘They must have blown what they had on all that cheap wine they were throwing down my neck.’

‘Don’t try to be funny, Steph. And don’t try to pull a fast one on me, neither. Now cough it up.’

‘Just what Detective McKinnon was always saying to me. I’ve still got his number somewhere, you know.’

Superficially, West’s anger dissipated but, internally, he was seething and they both knew it. ‘Don’t push your luck, Steph. One day, it’s gonna run out.’

‘I know. And so will yours. We’re both on borrowed time.’

Dean West raped me once. I say ‘raped’ because that is how it appears to me now but, at the time, I was less sure. Anne Mitchell was the one who introduced me to him. She was still a prostitute in those days, working for West, and I think she did it purely to please him although she said it was in my best interest. She told me that for a small percentage of my earnings he would provide protection for me and that, anyway, without his authority, I wouldn’t be allowed to operate in this area. That was a lie. So were most of the things that Anne said in those days. But I don’t hold that against her. She was no different to anyone else in this business, no different to me.

It occurred here, in Brewer Street, in the very room in which I am currently standing. In fact, I am looking at West right now and I am wondering if he is also thinking about it. It seems a lifetime ago. Or rather, it seems like another life altogether. Not mine, but someone else’s. I barely recognize the Stephanie who features in my memories. If I was ever really her, I no longer am.

As I entered this room on that morning, he was polite in an old-fashioned way. Courteously, he held out a chair for me to sit in. This, I later learned, was typical of West. One moment he’s charm itself, the next he’s a savage. I have never discovered whether this is genuine or whether it’s something he has cultivated but, either way, it’s part of his legend. What is beyond dispute is that West has always enjoyed his reputation as a man not to be crossed. He’s thirty-five years old and has spent twelve of his last nineteen years in custody.

To look at him, you would never think he was so vicious. There is nothing in his physique that suggests menace. He is not particularly tall – five-nine, I should think – and he’s very thin with fine features; he has hands as delicate and long-fingered as a female pianist’s. His lank, light-brown hair falls limply from a centre parting, giving a rather effeminate appearance. In a crowd, he is invisible. But when the rage is in him, the bulging eyes threaten to pop out of their sockets, the pale skin becomes so bloodless it almost looks blue and he radiates a feeling that is unmistakable: pure evil.

There is no bluff with West. Everyone knows it. If he says he’ll play noughts and crosses on your face with a pair of scissors, you know he will because if you know anything about him, you’ll know that he’s done it before. When I first entered this room, about two years ago, I never even noticed the screwdriver on the table next to where I was sitting.

At first, he told me how sexy I was, how I was going to make so much money. He told me that if there was anything I needed all I had to do was ask him. Then he came round from the other side of the desk, picked up the screwdriver and stood behind me, before stooping to whisper in my ear, ‘I want to see what you’ve got. And then I’m gonna try you out. Now get your clothes off.’

He never threatened me verbally, or with the screwdriver. He didn’t have to. And the fact that he didn’t somehow persuaded me at the time – and for some time after – that it wasn’t really rape. Now I know that it was because my compliance was automatic and was based on the certainty that, one way or the other, West would have sex with me. There was no choice in the matter. Compliance was self-preservation. And this was before I knew of his fearsome reputation. I could feel the menace and I knew it was genuine. I think he would have preferred me to protest, or even to struggle, just to provide him with some justification for violence. But I didn’t. Instead, I stripped and let him take me as he wanted. It was mechanical, brutal and painful but I never let it show.

This disappointed him. So over the following fortnight, he forced me to have sex with him on a dozen occasions. Each time, he was rougher than before, determined to provoke some reaction from me, but I never gave him that satisfaction. My icy composure remained intact, each humiliation only serving to strengthen me. Every time he finished, I held his gaze in mine and we’d both know whose victory it was. With every attempt to break me, West unmanned himself a little more.

I see now how stupid this was. Sooner or later, his patience would have snapped and I would have paid a fearful price for his humiliation. Fortunately, it never came to that.

An East End heroin peddler named Gary Crowther fell out with Barry Green over some money that Crowther owed. As a favour to Green, Dean West agreed to teach Crowther a painful lesson, choosing to deal with him personally. Unfortunately, Crowther had come off a Kawasaki on the M25 the previous year. The accident had left him with multiple skull fractures and had required two operations on the brain to save his life. West’s first punch knocked Crowther unconscious and he never recovered. What should have been a mere warning ended up as murder.

I never saw the blow that killed Crowther – by all accounts, it was more of a slap than a punch – but I did glimpse the unconscious body through a partially-opened door. Just for a second, but a second is all it takes.

I was the only witness that West couldn’t trust. Those who dumped theunconscious Crowther in Docklands were West’s closest men. They were never going to be a problem. But considering how he had treated me, West had every reason to be nervous.

Most of all, I remember the confusion in his face because I don’t think I’ve seen it since. He was truly scared. He knew that if he was convicted, he was looking at a life sentence. As for me, he wasn’t sure whether to try to sweet-talk me or whether to resort to violence. As it was, he did neither because I made up my mind before he made up his. I said to him, ‘If I was never here, you’re never going to touch me again. Do you understand?’

Dumbfounded, he’d simply nodded.

‘Let me hear you say it.’

‘I understand.’

Since then, I’ve kept silent and West has kept his word and Detective McKinnon – the officer who headed the investigation – has remained frustrated.

As for the rape – or should I say, the first rape? – I have analysed it constantly since it happened. I cannot pretend it was the brutal assault it could have been – the type that makes the news, the type that leaves a mutilated corpse in its wake – but it was a horror to be endured nevertheless. Having been endured, however, I think the experience has been strangely empowering. Primarily, having survived such an ordeal, it taught me that I could survive such an ordeal.

I began to be able to see myself as West saw me – as a thing, not a person – and this has enabled me to divide myself in two so that there is a part of me that nobody can reach, no matter what abuses they visit upon my body. This has allowed me to do what I do, to cope with the repulsive acts I perform for my repellent clients. It’s allowed me to live with the threat of violence without it driving me crazy.

West still makes me nervous and my hold over him is tenuous. There is no guarantee that I won’t become a victim of his violence at some point. As the months have passed and the Crowther incident has receded, West has become more intolerant of me. Thinly-veiled threats are starting to seep into our conversations. I’ve seen the way he looks at me and I know he’d like to try to break me again, even though he says I am no longer attractive, that I’m disgusting to him.

It is true that I don’t look good these days. I’ve lost so much weight. My skin has no real colour, except for the red blotches. My eyes look permanently bruised but aren’t and my gums are always bleeding.

Perhaps the most humiliating thing that has happened to me in this, the most humiliating of trades, is that I’ve been forced to lower my prices. Anneonce said to me, just as she was on her way out of the business and I was on my way in, ‘You don’t know what true degradation is until you have to discount yourself, only to find out it makes no difference.’

I am not in that position yet. But I am not far away.

I am twenty-two years old.

Joan was peeling the wrapper off her third packet of Benson & Hedges of the day. ‘You’re shaking.’

It was true. Stephanie’s hands were trembling. ‘I’m tired, that’s all.’

For Anne’s sake, she hadn’t returned to Chalk Farm, so the next two nights had been spent upon the lumpy sofa currently occupied by Joan’s sprawling bulk. Uncomfortable nights they had been, too; once the heating cut out, it had been freezing, so she’d curled herself into a ball and pulled two coats around her to keep warm. Then she’d sucked at the gin bottle until she’d passed out, managing three hours’ sleep the first night and two the second. Now she was paying the price for it.

Shrouded in smoke, Joan was chewing peanuts while flicking through the TV channels with the remote. On the floor, next to her overflowing ashtray, there were three phones, waiting for business. None of them was ringing. She said, ‘He’s ready when you are.’

‘What’s he like?’

‘Big bloke. I think he’s had a few.’ She glanced at Stephanie through her tinted lenses and shook her head. ‘Better pull yourself together, girl. You don’t look a million dollars.’

Joan looked like a beached whale. In Lycra. Stephanie said, ‘Who among us does?’

She poured herself half a mug of gin, stole one of Joan’s cigarettes, and went to the bathroom. She washed her face, the cold water bringing temporary refreshment, before applying foundation and mascara. When she looked this bad, Stephanie always tried to draw attention to her mouth and to her eyes, which were deep brown beneath long, thick lashes. The lipstick she selected was a bloodier red than usual. No matter how emaciated the rest of her became, her fleshy lips looked as ripe as they ever had.

She changed back into her lacy black underwear and fastened her suspender-belt. There were mauve smudges on her thighs, souvenirs from anonymous fingers that had pressed into her too eagerly. The bruises around her wrists had faded to a band of pale yellow that was barely noticeable.

She drained the gin, took a final drag from the cigarette and rinsed out her mouth with Listerine. Then she took a deep breath and tried to clear her mind. But when she caught her reflection in the mirror, the feeling returned; the fear of the stranger, the fear of fear itself. It was in her stomach, which was cold and cramping, and in her throat, which was arid and tight.

To the cadaverous face in the glass, she whispered a terse instruction. ‘No. Not now.’

‘Hi, I’m Lisa. What’s your name?’

He thought about it, presumably choosing something new. ‘Grant.’

Joan was right about his size. Not only was he tall, but he was massive. An ample gut hung over the top of black trousers that looked painfully tight. Stephanie never knew that Ralph Lauren shirts came in such a gargantuan size. His sleeves were rolled up to the elbow, exposing thick forearms, each of which sported a large tattoo. His hair was buzz-cropped and a band of gold hung from his left ear. But the watch on his wrist was a Rolex. He looked as if he was in another man’s things. He looked like an impostor. Then again, they nearly always did.

‘What are you looking for?’

He shrugged. ‘Dunno.’

Stephanie put her hand on her hip, as she always did at this moment, allowing her gown to fall further open. In the right mood, it felt like a tempting tease. Today, it felt cold and sad. She watched his eyes roll down her body. ‘I start at thirty and go up to eighty. For thirty, you get a massage and hand-relief. For eighty, you get the full personal service.’

‘Sex?’

She wanted to snap but managed to restrain herself, forcing a smile instead. ‘Unless you can think of something more personal.’

Grant frowned. ‘What?’

Stephanie saw the fog of alcohol clouding his eyes. ‘So, what do you want?’

‘The full … thing … service …’

‘That’s eighty.’

‘Okay.’ When he nodded, his entire body swayed.

‘Why don’t we get the money out of the way now?’

‘Later.’

‘I think now would be better.’

‘Half now, half after?’

‘No. Everything now. It’s better this way.’

His mouth flapped open, as though he were about to protest, but no sound emerged. So he stuffed a hand into his pocket and pulled out a fistful of fives and tens. As he came close, she smelt the alcohol on his breath and the body odour that is peculiar to sweat. With fat, pink fingers, he sorted through the grubby notes and handed them to her.

She counted quickly. ‘There’s only seventy here.’

‘It’s all I got.’

‘It’s not enough. Not for sex. Perhaps there’s something else you’d like?’

He grinned stupidly. ‘Come on,’ he slurred. ‘Ten quid. That’s all it is …’

‘Yeah, I know. Ten quid too little.’

‘It’s my birthday on Saturday.’

Stephanie was aware of her irritation rising to the surface, the blood flushing her skin. ‘So come back then. And make sure you bring your wallet.’

Her change in tone seemed to have a sobering effect upon him. He straightened. ‘What do I get for seventy?’