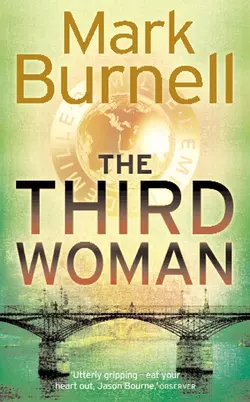

The Third Woman

The Third Woman

Mark Burnell

In a world where everyone and everything has its price, who do you trust? The Third Woman is a powerful and fascinating thriller following the adventures of Burnell’s unique heroine Stephanie Patrick. From conspiracy to terrorism, Vienna to Paris, will she find the truth?

The world isn't run by governments. It's run by corporations. In other words, everything and everyone has a price.

Stephanie Patrick operates under a number of names; Petra Reuter, known as a gun for hire, is probably the one she uses most frequently. She used to work for the government. Now she works for herself.

Robert Newman, who spends more nights at 35,000 feet than in his own bed, is an international troubleshooter. But twenty years at the top have still not purged for him the ghosts of the past.

A plea for help from an old friend draws Stephanie to Paris, where she narrowly survives a terrorist attack, an outrage that according to the authorities was masterminded by Petra Reuter. Betrayed in every way, pursued ruthlessly by a faceless enemy, her identity stolen from her, Stephanie seizes a hostage to give her a slim possibility of escape. But is the encounter with Robert Newman really just chance?

Hunted from Paris to Vienna, Stephanie and Newman are forced together to survive. Yet the more she learns, the closer Newman seems to be to the heart of the conspiracy. Stephanie becomes sure of only one thing: that the answers will lie with the person who she knows as The Third Woman.

‘The Third Woman’ is vividly contemporary, with a welcome return for a unique heroine

MARK BURNELL

THE THIRD WOMAN

Copyright (#ulink_832fe8ac-5cdb-5310-b8ed-913c29f9a0aa)

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2005

Copyright © Mark Burnell 2005

Mark Burnell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007152674

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2012 ISBN 9780007369904

Version: 2015-12-14

Dedication (#ulink_65a4b793-2ec1-5717-a9f0-e58f4b5b1285)

For Greta with love

Epigraph (#ulink_6fae5c1d-4ac0-5e2b-a126-f78eedf20eb0)

The true religion of America

has always been America.

NORMAN MAILER

Most people are other people. Their thoughts

are someone else’s opinions, their lives a

mimicry, their passions a quotation.

OSCAR WILDE

Contents

Cover (#u28193787-2b41-51e1-abee-e6350d8f5fa7)

Title Page (#ue894cdef-f627-5459-9e78-1d4407856097)

Copyright (#ufd8c12bc-53ed-592f-8aea-6237d3b74b59)

Dedication (#u5ff6abdd-9d26-5585-9689-c9f2164561cc)

Epigraph (#u8395b135-5ac4-5c3e-9adc-2b3c48f59d83)

Early October (#ud234b7dd-089e-54fc-9275-ba5a05aa5714)

Day One (#uccdbc3ba-c5b6-5760-b265-917a118c370c)

Day Two (#u0c86e0f2-72a8-5739-8e62-20d050df6a80)

Day Three (#u4677edc9-e9c8-5342-a3c7-6ab004cd3b73)

Day Four (#ucf66fc7b-079e-57a9-ad6f-71120ee4127f)

Day Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Early February (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Early October (#ulink_d2494ecf-48f1-5ac4-a021-5be75527921c)

He loved the ritual. It was as essential to his enjoyment of the countryside as the open space or clean air. A final stroll around the property before bed, the last of a cigar to smoke, the glowing embers of a good cognac warming his stomach. His only regret was that he didn’t come here often enough. Otto Heilmann stepped out of his dacha onto brittle grass; five below zero, he estimated, perhaps even ten.

His guests had gone to bed. Their cars were parked beside the boat-shed; a black Mercedes 4x4 with dark glass, and an Audi A8 with an auxiliary engine and armour-plating. Frost had turned both windscreens opaque.

Heilmann wandered to the edge of the lake, trailing clouds of breath and smoke. The silvery light of a three-quarter moon shone on the ice. He saw buttery pinpricks in the blackness of the far shore; two dachas, one belonging to a senior prosecutor from St Petersburg, the other to a Finnish architect.

There was no cloud and only the faintest whisper of a breeze. Heilmann smoked for a while. As Bruno Manz, a Swiss travel consultant based in St Petersburg, he felt a very long way from the grim years of the German Democratic Republic. A long way from Erich Mielke, his Stasi boss during those years, and a long way from Wolfasep, the ubiquitous industrial-strength detergent that was the defining odour of the Honecker regime for millions of East Germans. Once smelled, never forgotten, a scar of memory.

He tossed his soggy cigar stump onto the ice and continued his circuit. Along the lake shore, past the creaking jetty, up towards the wood-shed.

‘Hello, Otto.’

A female voice. He thought he recognized it. Except she was supposed to be in Copenhagen. But it was her face that emerged from the darkness of the birch forest.

Heilmann clutched the coat over his chest. ‘I hope you know what to do if I have a heart attack.’

Krista Jaspersen stared deep into his eyes and smiled. ‘Don’t worry, Otto. I’ll know exactly what to do.’

He wasn’t reassured.

She was wearing thick felt boots, a great overcoat and the sable hat he’d given her two nights ago at the Landskrona restaurant on top of the Nevskij Palace Hotel in St Petersburg.

He tried to recapture his breath. ‘What are you doing, Krista?’

‘Waiting for you.’

‘Out here?’

‘I remembered your routine.’

An answer of sorts, Heilmann conceded, yet hardly adequate. ‘You could have phoned to say you were coming. Like normal people do.’ He glanced over one shoulder, then the other. ‘How did you get here?’

‘By car.’

‘I mean … here.’

‘The men at the gate let me through.’

‘Just like that?’

‘Just like that.’

She looked the same – long fair hair, dark green eyes, a mouth of invitation – but she was radiating a difference that Heilmann couldn’t quite identify.

‘It’s freezing,’ he said. ‘Let’s go inside.’

‘You have guests.’

‘They’re asleep.’

‘I’m not staying, Otto.’

‘The mystery is why you’re here at all. You should be in Copenhagen.’

Krista reached inside her coat and pulled out a gun. A SIG-Sauer P226. Moonlight glittered on a silencer.

There was no outrage. That surprised her; Heilmann had a notoriously fragile temper. Instead, after a digestive pause, he simply nodded glumly and said, ‘Let me take a guess: you’re not even Danish.’

She shook her head. ‘Not really, no.’

‘Who are you?’

The seconds stretched as they stared at each other, eyes watering in the cold, neither prepared to look away.

‘The stupid thing is, I knew it,’ he murmured. ‘In my head, I knew it. But I let my heart overrule and …’

‘More likely it was another part of your anatomy.’

‘You were too good to be true. That was my initial reaction to you.’

‘I’ve been accused of many things but never that.’

A deep breath deflated slowly. ‘So … what is it?’

‘You’ll never guess.’

‘The ghosts of the past?’

‘That doesn’t narrow the field much, does it? Not after your glittering career with the Stasi. But no, it’s not that.’

His surprise seemed genuine. He considered another option. ‘The S-75s?’

Krista smiled. ‘I knew you’d say that.’

The S-75 air defence missile was a relic of the Soviet era, prominent in conflicts from Vietnam to the Balkans. Hundreds of them had been transported from the nations of the Warsaw Pact to the Ukraine for decommissioning and dismantling. Many had vanished into thin air, leaving no trace, a feat made possible by the astonishing elasticity of the accounting practices at the Ukrainian Defence Ministry.

‘Scrapyard junk,’ Heilmann declared.

‘Maybe. But you know what they say about muck and brass. How much time have you spent in Kiev over the last decade?’

‘I don’t know. Plenty. What is your point, Krista?’

‘Otto Heilmann, store manager at the Ukraine Hypermarket, flogging the decrepit remains of the Soviet arsenal to Third-World psychopaths. A lucrative business judging by the way you live, Otto. And better than pulling fingernails out of old ladies in the damp cellars of Leipzig, I imagine. The gap in the military inventory from the Soviet era – how much would you say it’s worth today?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘The figure I hear most often is $180 billion. But I’ve heard higher. Last year, the Ukraine’s spending budget was $10 billion. In terms of a trading environment I’d say that left plenty of room for manoeuvre. What do you think?’

‘Is that what this is about? Missing missiles?’

‘Two hundred of them.’

‘They’re museum pieces.’

‘There’s value in antiquity, Otto. Even in yours,’ Krista smiled coldly. ‘Actually, that’s not what this is about. But it’s nice to know I was right about you. No, this is a private matter.’

‘Between you and me?’

‘Between you and your bank.’

‘My bank?’

‘You’ve over-extended yourself, Otto.’

‘So here you are? With a gun?’

‘That’s right.’

‘That’s shit. I have business with a lot of banks. Which one?’

‘Guderian Maier.’

Heilmann looked incredulous. ‘You work for them? I don’t believe you.’

‘You made a mistake in Zurich.’

‘And you’re making one here.’

‘Your money’s no longer any good.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Most bank managers send you a letter. Yours has sent me.’

Heilmann snorted dismissively. ‘Very funny. But banks don’t shoot people. So no more games, okay? Just tell me. Why are you here?’

Krista Jaspersen raised the SIG-Sauer P226. ‘I’ve come to close your account, Otto. Permanently.’

Day One (#ulink_d18114b0-fe14-50e3-96f1-b66d9ae1b2d4)

When she opened her eyes, the face beside her was a surprise. She’d expected to be alone in the bedroom of her crumbling apartment off boulevard Anspach. Instead, she found herself in a room with curtains, not shutters, a room overlooking avenue Louise, not rue Saint-Géry.

Brussels, twenty-to-seven on a bitter January morning. Outside, a tram grumbled on the street below. She’d always liked the sound of trams. Next to her, Roland was still asleep, half his head lost in the quicksand of a pillow. Stephanie pulled on his blue silk dressing-gown, which was too big for her, and rolled up the sleeves. In the kitchen, she poured water into the kettle and switched it on.

Gradually, she recalled a day that had started in Asia. She’d called Roland from the airport at Frankfurt while waiting for her connection to Brussels and again when she’d touched down at Zaventem. Earlier, in Turkmenbashi and then on the Lufthansa flight back from Ashgabat, she’d been aware of the familiar sensation; the seep of corruption that always followed the adrenaline rush. She’d needed Roland because she couldn’t be alone.

His bathroom belonged in a hotel; heated marble floor, marble sink, fluffy white towels folded over a ladder of hot chrome rails, a soap dish full of Molton Brown miniatures. Typical, really; a bathroom at home to remind him of the hotels he used abroad. Still, lack of imagination in a man was not always a disadvantage.

She showered for five minutes. Stepping on to the white bath-mat in front of the mirror, Stephanie saw Petra Reuter looking back at her. Her other self, the differences between them at that moment counting for nothing, though the body they shared now belonged more to Petra than Stephanie. In that sense, it was a barometer of identity. Where Petra favoured muscular definition, Stephanie slipped happily into softness.

She ran a hand over the stone ripple of her abdomen and looked into a pair of hard, dark eyes. Only her mouth appeared warm and inviting; there was nothing she could do about those generous lips. The rest of her looked cold and mean. When she was in this mood, even the slight bump on her nose – courtesy of two separate breaks – looked large and ugly. Worse was the cosmetic bullet-wound through her left shoulder. In forty-eight hours, beneath an Indian Ocean sun, Stephanie knew she’d despise it; Petra’s badge of honour was a reminder of the life she couldn’t escape.

She dressed in the crumpled clothes she’d scooped off Roland’s sitting-room floor; dark grey combat trousers with a neon-pink stripe down each leg, two T-shirts beneath a Donna Karan jersey and a pair of Caterpillar boots.

Towelling long, dark hair she returned to the kitchen, made coffee, then took two mugs to the bedroom, setting one on Roland’s bedside table. He began to stir. She drew the curtains. On avenue Louise, the first hint of rush-hour, headlights slicing through drizzle.

From behind her came a muffled murmur. ‘Marianne.’

Stephanie turned round. ‘You look a little … crumpled.’

Roland grinned, pleased at the description, then propped himself up on an elbow and patted the mattress. ‘Come back to bed.’

‘I’ve got to go.’

‘So have I. Now come back to bed.’

‘Exactly what kind of investment bank do you work for?’

‘The kind that understands a good worker is a happy worker.’

The candle of temptation flickered briefly. Generally, the more attractive the man the more cautious Stephanie was. In her experience, good-looking men tended to make lazy lovers. Not Roland, though.

‘Last night,’ he said, reaching for the mug, ‘that was really something.’

If only you knew.

A surgical procedure to cut away tension. That was what it had been. There, on the floor of the entrance hall, tenderness cast aside as roughly as their clothes. Around nine, they’d gone out to eat at Mont Liban, a Lebanese place on rue Blanche, a couple of minutes’ walk away. By the time they’d returned to his apartment, her desire had been back, less frantic but just as insistent. Which was how her clothes had ended up on his sitting-room floor.

Strange to think of it now, like an out-of-body experience. Roland was staring at her through the steam rising from his coffee, his disappointment evident.

‘What are you thinking?’ she asked.

‘That I went to bed with one person and woke up with another.’

Stephanie said, ‘I know the feeling.’

It’s no longer raining when I step on to avenue Louise. Winter blows shivers through the puddles and snaps twigs from the naked plane trees. Ahead, the rooftop Nikon and Maxell signs are backlit by a cavalry charge of dark cloud.

Brussels; bitter, grey, wet. And perfect.

This city at the heart of the European Union is an ideal home for me. It’s a city of bureaucrats. In other words, a city of transient people who shy from the spotlight and never have to account for their actions. People like me.

In some respects, the city is an airport hub. When I’m here, there’s always the feeling that I’m passing through. That I’m a stranger in transit, even in my own bed.

I had a proper home once. It didn’t belong to me – it belonged to the man I loved – but it was mine nevertheless. It was the only place I’ve ever been able to be myself. And yet he never knew my name or what I did.

With hindsight, civilian domesticity – Petra’s professional life running in parallel to Stephanie’s private life – was an experiment that failed. I took every precaution to keep the two separate, to protect one from the other. But that’s the truth about lies: you start with a small one, then need a larger one to conceal it. In the end, they swamp you. Which is exactly what happened. One life infected the other and was then itself contaminated. The consequences were predictable: I hurt the ones I loved the most.

These days I no longer delude myself. That’s why I live in Brussels but spend so little time here. It’s why I was in Turkmenistan the day before yesterday and why Eddie Sullivan’s obituary is in the papers today. It’s why I see Roland in the way that I do and it’s why he calls me Marianne.

He became my lover in the same way that Brussels became my home; by chance and as a matter of temporary convenience. Random seat assignments put us together. We met on a train, which seems appropriate; sensory dislocation at two hundred miles an hour. All very contemporary, all very efficient. There is no possibility that I will ever give anything of my soul to him. For the moment, however, like the city itself, he serves a transitory purpose.

Rue Saint-Géry, the walls smeared with graffiti, the pavements with dog-shit. Home was a filthy five-storey wedge-shaped building with rotten French windows that opened onto balconies sprouting weeds. The bulb had gone in the entrance hall. From her mail-box she retrieved an electricity bill and a mail-shot printed in Arabic. The aroma of frying onions clung to the staircase’s peeling wallpaper.

Stephanie’s apartment was on the third floor; a cramped bedroom and bathroom at the back with a large room at the front, one quarter partitioned to form a basic kitchenette. There were hints of original elegance – tall ceilings, plaster mouldings, wall panels – but they were damaged, mostly through neglect.

Her leather bag was where she’d left it late yesterday afternoon, at the centre of a threadbare rug laid over uneven stained floorboards. The luggage tag was still wrapped around a handle. So often it was the smallest detail that betrayed you. In the past she’d been supported by an infrastructure that ensured there were no oversights, no matter how trivial. These days, as an independent, there was no one.

On the floor by the fireplace a cheap stereo stood next to a wicker basket containing the few CDs she’d collected over ten months. They were the only personal items in the apartment. She slipped one into the machine. Foreign Affairs by Tom Waits; more than any photograph album could, it mainlined into the memory.

The first albums she’d listened to were the ones she’d borrowed from her brother: Bob Dylan, Bringing It All Back Home; David Bowie, Heroes; The Smiths, The World Won’t Listen. She remembered being given something by Van Morrison by a boy who wanted to date her. Not a good choice. She’d disliked Van Morrison then and still did.

Elton John’s ‘Saturday Night’ had been the song playing on the radio the first time she sold herself in the back seat of a stranger’s car. Every time she heard the song now, that same meaty hand grasped her neck, jamming her face against the car door. The same fingernails drew bloody scratches across her buttocks. Later, she’d been routinely brutalized and humiliated but nothing had ever matched the emotional impact of that initiation. She felt she’d been hung, drawn and quartered. And that the music coming from the tinny radio in the front had somehow been an accomplice.

Sometimes mainlining into the memory was as risky as mainlining into a vein; you didn’t necessarily get the rush you were depending on. So she changed the CD to Absolute Torch & Twang, a k.d.lang album she’d discovered as Petra.

Petra meant no bad memories. In fact, no memories at all.

She emptied the leather bag. Dirty clothes, a roll of dollars, a wash-bag containing strengthened catgut in a plastic dental-floss dispenser, an Australian passport in the name of Michelle Davis, a ragged copy of Iain Pears’s An Instance of the Fingerpost and a guide to Turkmenistan featuring out-of-date maps of Ashgabat and Turkmenbashi.

In the bathroom, beneath the basin, she kept a battered aluminium wash-bowl. She shredded the passport, luggage tag, receipts and ticket-stubs, then dropped them into the bowl, which she placed on the crumbling balcony. She squirted lighter fuel over the remains and set light to them. A small funeral pyre for another version of her.

There were four messages on the answer-phone including one from Tourisme Albert on boulevard Anspach. Your tickets are ready for collection. Shall we courier them to you or would you like to collect them from our office? She looked at her watch. In thirty-six hours, she would be gone; a fortnight in Mauritius, intended as a buffer between Turkmenistan and the next place. Yet again, a woman in transit.

In her bedroom, she shunted the single bed to one side, rolled back the reed mat and lifted two loose floorboards. From the space below she recovered a small Sony Vaio laptop in a sealed plastic pouch.

Back in the living-room, she switched on the computer and accessed Petra’s e-mails. Spread over six addresses, split between AOL and Hotmail, Petra hid behind four men and two women. She checked Marianne Bernard’s mail at AOL; one new message. Roland, predictably. Gratitude for the best night of the year. Not the greatest compliment, Stephanie felt, in early January.

She sent one new message. To Stern, the information broker who also acted as her agent and confidant. It had to be significant that almost the only person she truly trusted was someone she had never met. She didn’t even know whether Stern was a man or a woman, even though she called him Oscar.

> Back from the Soviet past. With love, P.

She left the laptop connected, then took her dirty clothes to Wash Club on place Saint-Géry. She bought milk and a carton of apple juice from the LIDL supermarket on the other side of the square, then returned home to find two messages waiting for her. One was from Stern. He directed her to somewhere electronically discreet and asked:

> How was it?

> Turkmenistan? Or Sullivan?

> Both.

> Depressing, dirty and backward. But Turkmenistan was fine.

Eddie Sullivan was a former Green Jacket who’d established a company named ProActive Solutions. An arms-dealer with a flourishing reputation, he’d been in Turkmenistan to negotiate the sale of a consignment of weapons to the IMU, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. The hardware, stolen from the British Army during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq, was already in Azerbaijan, awaiting transport across the Caspian Sea from Baku to the coastal city of Turkmenbashi.

Petra’s contract had been paid for by Vyukneft, a Russian oil company with business in Azerbaijan. But Stern had told her that the decision to use her had been political. Made in Moscow, he’d said. Hiring Petra meant no awkward fingerprints. It wasn’t the first time she’d worked by proxy for the Russian government.

The final negotiation between Sullivan and the IMU had been scheduled for the Hotel Turkmenbashi, a monstrous hangover from the Soviet era. Hideous on the outside, no better on the inside, she’d eliminated Sullivan in his room, while the Uzbek end-users gathered two floors below. She’d masqueraded as a member of hotel staff, delivering a message with as much surliness as she could muster.

Distracted by the imminent deal, Sullivan had been sloppy. He’d never looked at her, even as she loitered in the doorway waiting for a tip. When he’d turned his back to look for loose change, she’d pulled out a Ruger with a silencer and had kicked the door shut with her heel. The gun-shot and the slam had merged to form one hearty thump. Two minutes later she was heading away from the hotel on the long drive back to Ashgabat and the Lufthansa flight for Frankfurt.

> Are you available?

> Not until further notice.

> Taking a vacation?

> Something like that. Anything on the radar?

> Only from clients who can’t afford you.

> Then your commission must be fatter than I thought.

> Petra! Please. Don’t be cruel.

The second message, at one of the Hotmail addresses, was a real surprise. No names, just a single sentence.

> I see you chose not to take the advice I gave you in Munich.

Petra Reuter was sipping a cappuccino at a table close to the entrance of Café Roma on Maximilianstrasse. It was late September but winter had already made its presence felt; two days earlier there had been snow flurries in Munich.

The man rising from the opposite side of the table was Otto Heilmann. A short man, no more than five-foot-six, with narrow sloping shoulders, he wore a loden hunting jacket with onyx buttons over a fawn polo-neck.

‘We will meet again, Fräulein Jaspersen?’

‘I expect so, if you wish.’

‘Perhaps you would consider coming to St Petersburg?’

Petra wondered where this stiff courtesy came from. Probably not from two decades with the Stasi. Nor from the last fifteen years of arms-dealing. She didn’t imagine there was much call for Heilmann’s brand of politeness in Tbilisi or Kiev. Or even in St Petersburg. Yet here he was, dressed like a benevolent Bavarian uncle, hitting on her with a formal invitation that fell only fractionally short of stiff card and embossed script.

She gave him her best smile. ‘I’d certainly consider it, Herr Heilmann.’

‘Please. Otto.’

‘Only if you promise to call me Krista.’

A small inclination of the head was followed by a reciprocated smile that revealed a set of perfectly calibrated teeth. ‘This could be the beginning of something very good for us, Krista.’

She watched him leave, a navy cashmere overcoat folded over his right arm. Outside, a Mercedes was waiting, black body, black windows, a black suit to hold open the door for him. Perhaps that was why he’d chosen Café Roma; black wooden tables, black banquettes, black chairs. Crimson walls, though. Like blood. A more likely reason for Heilmann to choose the place. Her eyes followed the car until it faded from view.

The remains of the day stretched before her. Nothing to do but wait for the call. More than anything, Petra’s was a life of waiting. Like a movie actor; long periods of inactivity were intercut with short bursts of action.

She drained her cappuccino and decided to order another. Twenty minutes drifted by. It grew busier as afternoon matured into evening; shoppers, businessmen and women, mostly affluent, mostly elegant.

‘Jesus Christ, I don’t believe it. Petra, Petra, Petra …’

She looked up and took a moment to staple a name to the face. Not because she didn’t recognize him but because he was out of context.

He misunderstood her silence. ‘Or are we not Petra today?’

John Peltor. A former US Marine. Still looking every inch of his six-foot-five.

‘Is this bad timing?’ he asked.

‘That depends.’

He glanced left and right. ‘Am I intruding?’

‘No.’

Clearly not the answer he was expecting. ‘You’re alone?’

‘Aren’t we all?’

‘Always the smart-ass, Petra.’

‘Always.’

‘I wasn’t sure at first. The hair, you know.’

It was the longest she’d ever worn it. Halfway down her back and dark blonde.

‘Kinda suits you,’ he said.

‘Do you think so?’

She didn’t like it: although it went well with her eyes, which were now green. She wasn’t sure Peltor had noticed that change.

He looked into her cup, which was two-thirds empty. ‘Want another?’

‘I’ve got to go,’ she lied.

‘You sure? It would be good to catch up again.’

Perversely, that was true. Social opportunities in their solitary profession were rare although it wasn’t the first time they’d run into each other by chance. Peltor wasn’t her type but that hardly mattered. How many of them were there in the world? Not the cheap battery-operated types, but those rare hand-crafted precision instruments. Less than a hundred? Certainly. Whatever their respective backgrounds they were bound by the quality of their manufacture and they both knew it.

‘How long are you in Munich?’ she asked.

‘Leaving tomorrow, around midday. How about tonight?’

‘Busy.’

Another lie.

‘Can you make breakfast? At my hotel. Say nine?’

Petra tilted her head to one side and allowed herself a smile. ‘You won’t be sharing it with some lucky lady?’

Peltor feigned wounded pride. ‘Not unless you say yes.’

Petra arrived at the Mandarin Oriental on Neuturmstrasse at nine. When she asked for Peltor at the front desk – ‘Herr Stonehouse, bitte’ – her instructions were specific: he was running a little late so could she take the lift to the sixth floor, the stairs to the seventh and then proceed up to the roof terrace.

It was a freezing morning, no hint of cloud in the sky. The sun sparkled like the Millennium Star over a roof terrace that offered an unobstructed view of all Munich.

‘Not bad, huh? It’s why I always stay here when I’m in town.’

Peltor was floating at one end of a miniature swimming pool. Petra had seen baths that weren’t much smaller.

‘I hope that’s heated.’

‘A little too much for my taste.’

‘Always the Marine, right?’

Petra looked at the board by the pool. Next to the date was the air temperature taken at seven-thirty. One degree centigrade.

‘Love to swim first thing in the morning,’ Peltor declared loudly.

‘I thought you people loved the smell of napalm in the morning.’

‘Not these days. How long’s it been, Petra?’

‘I don’t know. Eighteen months?’

‘More like two years. Maybe longer.’

‘The British Airways lounge at JFK? You said you were going to Bratislava. Two weeks later I was stuck in Oslo airport flicking through a copy of the Herald Tribune and there it was. Prince Mustafa, the Mogadishu warlord, hit through the heart by a long-range sniper. A Sako rifle …’

‘A TRG-S,’ Peltor added. ‘Won’t use any other kind …’

‘A 338 Lapua Mag from seventeen hundred metres, wasn’t it?’

‘Seventeen-fifty. What were you doing in Oslo?’

‘Nothing. I told you. I was stuck.’

‘Cute, Petra. Real cute.’

Peltor climbed out of the pool. Massive shoulders tapered to a waist so narrow it was almost feminine, a feature that reminded her of Salman Rifat, the Turkish arms-dealer. But where Rifat’s extraordinary physique was steroid-assisted, Peltor’s was natural. He exuded power as tangibly as the steam coming off his skin.

Oblivious to the cold, he dried himself in front of her, neither of them saying anything. It was an extravagant performance. A muscled peacock, Petra thought, as he reached for a dressing-gown. She wondered whether he was really running late or whether he’d orchestrated the display deliberately.

His suite was on the seventh floor. He emerged from the bathroom in a navy suit without a tie. Stephanie caught a trace of sandalwood in his cologne. Peltor wore a trim goatee beard at the same thickness as the hair on his head, somewhere between crop and stubble. He stepped into a pair of black Sebago loafers and they went down to Mark’s, the hotel restaurant.

Orange juice and coffee arrived. Peltor ordered scrambled eggs and bacon, Petra stuck with fruit and croissants. She said, ‘You running into me at Café Roma yesterday …’

He took his time, sipping coffee, playing with the teaspoon on the saucer. ‘Yeah. I know.’

‘And?’

He struggled for an answer, then looked almost apologetic. ‘All my adult life, I’ve had my finger on a trigger, Petra. First for my country, then for my bank balance. In that time, I’ve been the best there is. We both have. Different specialities, same environment. But nobody knows what we do. We have to lie to everyone. We can’t relax. That time at JFK – we were just a couple of business colleagues shooting the breeze in an airport lounge. A few stories, a few drinks. It was nice. But I didn’t think I’d get the chance to do it again. Then yesterday … there you were.’

‘A coincidence?’

‘I hope so.’

‘Someone I used to know said that a coincidence was an oversight.’

He sat back in his chair and held open his hands. ‘Shit, it happens, you know? You’re walking down a street somewhere – Osaka, Toronto, Berlin – and some guy calls out your name. When you turn round there’s a face you haven’t seen since the fourth grade back in Austin, Texas.’

‘Is that where you grew up?’

‘Never let your defences down, do you?’

‘Never.’

Peltor held up his hands in mock surrender. ‘Look, I saw you in Café Roma. I could’ve walked away but I didn’t. That’s all there is to it. I just thought we could talk again like we did in New York. You know, take a time-out. If you’re uneasy with that … well, then I guess you’ll leave.’

But she didn’t. Perhaps because she’d enjoyed JFK too. Taking a time-out, talking shop. Relaxing.

Peltor’s eggs and bacon arrived. The waitress poured Petra more coffee. The restaurant was mostly empty, the businessmen long gone, just four other tables occupied, none of them too close.

Gradually, they drifted into conversation. Nothing personal, not at first. They talked about Juha Suomalainen, a Finnish marksman whom Peltor had always regarded as a rival rather than a kindred spirit. Petra asked whether he was still active.

‘I doubt it. He’s been dead for six months.’

‘Who got him?’

‘Husqvarna.’

‘I don’t know the name. Sounds Nordic.’

‘Husqvarna make chainsaws.’

‘I’m not with you.’

‘Juha was at his home in Espoo. Up a ladder, cutting branches off a tree. Somehow he fell and the chainsaw got him. And before you ask, I was in Hawaii with a drink in my hand.’

Petra pulled apart a croissant. ‘Well, statistically speaking, this is a risky business. You just don’t expect any of us to go like that.’

‘Right. Like Vincent Soares. Cancer. Wasn’t even forty-five.’

When Peltor talked about his time as a Marine, Petra was surprised to learn that he wasn’t the rabid jock-patriot she’d suspected he might be, although he admitted to missing the comradeship. But not much.

‘This is a lot better. Like owning your own business, know what I mean? You work hard but you got no boss busting your ass.’

As far as Peltor was concerned, she’d always been Petra Reuter, the anarchist who turned assassin. Originally, however, Petra had been created by an organization. And controlled by that organization. Petra was an identity handed to Stephanie. A shell to inhabit. And in those days there had been a boss. A man who had regulated every aspect of her life. But as time passed, flesh and fabric had merged and Stephanie had become Petra. Or was it the other way round? In any case, Petra had outgrown her fictional self. Now, both the organization and the boss were consigned to her past while Petra Reuter was more of a reality than she had ever been.

Peltor ate a piece of bread roll smeared with butter and marmalade. Petra waited for the predictable reaction: the grimace. He picked up the small marmalade jar.

‘Look at this, will you? Look at the colour. Way too light. Like dirty water. Too much sugar, not enough orange. And no bitterness. Marmalade doesn’t work unless there’s a trace of bitterness.’

When he wasn’t killing people Peltor liked to make marmalade. The first time she’d discovered this she’d laughed out loud. Later, when she thought about it, it simply reinforced a truth: you can never really know someone.

‘You still getting the same kick out of it?’ she asked.

When they’d last met, Peltor had explained what drove him on: the quest for perfect performance. It all comes down to the shot, Petra. Last contract I took was nine months from start to finish. All of it distilled into half a second.

There was no longer any trace of that enthusiasm. ‘To be honest, I’m not sure I’ll take another contract.’

‘That surprises me.’

‘I’m kinda drifting into something new right now.’ He tugged the lapel of his jacket. ‘Something … corporate.’

‘That surprises me more.’

‘It shouldn’t. You know the way the math works. I’ve had my time at the plate, Petra. And if you don’t mind me saying so, so have you.’

‘If you don’t mind me saying so, I’d guess you’re a decade older than me.’

It was more like fifteen years, but technically Petra was older than Stephanie.

‘It’s not about age. It’s about time served.’

She reduced her indifference to a shrug. ‘I’m touched by your concern.’

‘Don’t outstay your welcome, Petra. Most of the assholes out there – I couldn’t give a rat’s ass if they get wasted. But I like you. You got class. Don’t be the champ who doesn’t know when to quit.’

‘When it’s time, I’ll know.’

‘Bullshit. The people who say that never know. Know why? Because the second before they realize it, they find their brains in their lap.’

‘I’ll try to remember that.’

‘Just do it. Retire. Or shift sideways like I have.’

‘What is this venture, then?’

‘Consultancy I’d guess you call it. First-class travel, expense accounts, places like this. I swear, there are corporate clients out there – the biggest names – ready to pay a fortune for what we have up here.’

Petra watched him drum a finger against the side of his head and said, ‘Not quite the double-tap I’ve come to associate with you.’

‘Funny girl. Seriously, though, you can name your price. They pay off-shore, share options, anything you want.’

‘Now I’ve heard it all.’

‘You’re not too young to think about it, Petra.’

‘It’s not that.’

‘No?’

‘No.’

‘So what is it?’

‘You know perfectly well. It’s obviously already happened to you. But it hasn’t happened to me. Not yet.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘The moment.’

Peltor’s evangelism sobered into silence and she knew she was right.

She said, ‘The moment you know. But before that moment … well, you don’t just retire from this life, John. You know that as well as I do. It retires you. Sometimes after just one job.’

Beyond the recognition, she thought she detected a hint of regret in his voice when, eventually, he said, ‘Damned if you’re not right, Petra. Damned if you’re not right.’

Stephanie was still thinking about Peltor’s e-mail and the meeting that had prompted it back in September when her taxi pulled up beside the church of Notre Dame du Sablon. When Albert Eichner had told her that he was coming to Brussels to take her to lunch, she’d been faintly amused by his choice of restaurant. The exterior of L’Écailler du Palais Royal was the essence of discretion; premises that were easy to miss, the name lightly engraved on a small stone tablet beside the door, net curtains to prevent inquisitive glances from the street. As the chairman of Guderian Maier Bank in Zurich, these were qualities that Eichner appreciated more than most.

He was at a table towards the rear of the restaurant, a solid man with a physique that had defeated his tailor. When she’d first met him his thick head of hair had been gun-metal grey. Now it was almost as white as his crisp cotton shirt. Each cuff was secured by a thick oval of gold. On his left wrist was an understated IWC watch with a leather strap.

Stephanie was wearing the only smart outfit she now possessed, a black Joseph suit with a plain, cream silk blouse. Chic and conservative, just the way she suspected she existed in Eichner’s imagination. As she approached the table he rose from his chair.

‘Stephanie, as beautiful as ever.’

Eichner was one of the few men Stephanie had entrusted with her original given name. As for the surname with which he was familiar – Schneider – that had been her mother’s.

A waiter in a blue tunic poured her a glass of champagne.

She said, ‘How long are you in Brussels, Albert?’

‘A friend of mine lent me his Bombardier. I flew here from Zurich this morning. I have to get back for a family engagement this evening.’

‘I’m flattered.’

‘Don’t be. You’ve earned it.’ He raised his glass. ‘To you, Stephanie. With our sincerest gratitude.’

It was three months since Otto Heilmann’s death. She smiled but said nothing. Eichner was right to be grateful. In the past, she’d saved him from personal disgrace and in return he’d consented to become her banker. This time, however, the entire institution had been under threat. In the first week of September, Eichner had implored her to come to Zurich. An emergency, he’d said. An emergency that threatened Guderian Maier. He’d let her fill in the blank spaces.

An emergency that threatens your arrangement with us.

Otto Heilmann. One of the very few to have become rich during the era of the GDR. Heilmann had links with Guderian Maier going back to the Seventies. When Stephanie had asked what kind of links, Eichner had reddened.

‘In those days, my uncle ran this bank. In the same way that he did when he first ran it back in the Forties.’ He’d paused to let her dwell on this, the gravity in his voice suggesting the subtext. ‘We do things differently these days. Heilmann doesn’t understand that. He’s of the opinion that a bank like ours will accept anyone’s money providing there is enough of it.’

‘I assume you’ve explained that this isn’t the case.’

‘As politely and as firmly as possible.’

‘But he’s not dissuaded?’

‘Unfortunately, no.’

‘Distressing.’

‘We can’t possibly be associated with an arms-dealer.’ When Stephanie had raised an eyebrow at him, Eichner had qualified himself. ‘Not like Heilmann. It’s simply out of the question. You know the kind of clients we have. The very idea of it is just too … appalling.’

‘I’d have thought your stand might have worked in your favour.’

‘On one level, possibly. But there’s something else. When the Stasi disintegrated, Heilmann headed to Russia and took what he needed with him. Information for his own protection, information for profit.’

‘Let me guess. You refuse him and he’ll find a way to incriminate the bank, tying it to the crimes of the Stasi.’

‘He won’t find a way. He has a way.’

‘The sins of the past …’

The traffic on Bahnhofstrasse and the ticking of the carriage-clock on the marble mantelpiece had provided the soundtrack to a moment of awkward truth.

Eventually, Eichner had said, ‘As I have already explained to you, Stephanie, we don’t behave that way any more.’

‘Yet you have me as a client.’

He’d smiled lamely. ‘The point is, my generation and the next generation have gone to great lengths to restore some honour to a very noble heritage. Despite that, if we had to, we would be prepared to face the potential humiliation he’s threatening. But it’s gone beyond that now.’

He’d slid a photograph across his desk. Stephanie had recognized Eichner at the heart of the gathering, his wife sitting to his right. A family portrait, the faces of their seven grandchildren scratched out by a sharp point.

‘Hand-delivered to this office last week. Six people in the bank have received similar material. Including my secretary.’

She’d told him not to worry. And when he’d raised the subject of her fee, she’d refused to discuss it. Consider it a gift, she’d said. From one friend to another.

Now, four months after that conversation, Eichner looked five years younger. ‘Shall we share a bottle of something good? The seafood here is fantastic but I hope you won’t be offended if we drink red wine. From memory, they have a very fine Figéac 93 but I think we’ll go for something a little better.’

He ordered for both of them, Iranian caviar with another glass of champagne, followed by grilled turbot and a bottle of Cheval Blanc 88. When they were alone again, he said, ‘That place you used to live – that farm in the south of France – remind me where it was.’

Her heart tripped. ‘Between Entrecasteaux and Salernes.’

‘Were you aware that it’s for sale?’

How many years was it since she’d been there? Four, perhaps? It felt longer. She’d rented it. The owner had been a German investment banker stationed in Tokyo. It was a beautiful place, a little run-down, terraces rising behind the house, olives, lemons, a vineyard falling away to the valley below, the house itself afloat on clouds of lavender bushes. She’d picked it as somewhere to hide from the world and had never wanted to leave.

‘The directors and I have discussed this and – with your permission, naturally – we have decided to acquire the property.’

Stephanie frowned. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘For you. As a token of our gratitude.’

‘I told you in Zurich that I would deal with Heilmann for free.’

‘Exactly so. And we would like you to view this gesture in the same spirit. Consider it a gift. From one friend to another.’

She reached across the table and took his hand. ‘Thank you, Albert. That’s so sweet of you. But I’ll need to think about it.’

‘Is that you, Petra?’

Ten-to-eleven. When the call came, she was sitting on the living-room floor, sorting through Marianne’s domestic bills, listening to Bright Red by Laurie Anderson. The track ‘Tightrope’ was on repeat.

Roland doesn’t know me as Petra. That was her first thought, quickly followed by another: it’s not his voice.

‘Who is this?’

‘Jacob Furst.’

Out of the blue. Or, to be accurate, out of the past.

Furst took her silence incorrectly. ‘You don’t remember me?’

‘Of course I remember you.’

Furst was an old man – in his late eighties now, she guessed – with each year etched into the timbre of his voice. Not surprising, given the life he’d led. And now she recognized the strangely distinct sound of that voice too; high and quavering, almost feminine.

‘I apologize for calling you like this but I need to see you. It’s urgent.’

Another thought was forming; this was Marianne’s mobile phone. How had Furst obtained the number? Through Cyril Bradfield, perhaps, a mutual friend. Stephanie felt Petra taking over, concern making way for pragmatism. ‘Where are you?’

‘Paris.’

Where Furst lived, so far as she knew. ‘I’m going away tomorrow but I’ll be back …’

‘Where are you?’

She felt Petra’s reflex, her mobile had a German number. Did Furst imagine she was in Germany, or did he know that she was in Belgium?

‘I’m right … here.’

He seemed to understand. ‘Could you be in Paris tomorrow?’

‘I could be just about anywhere tomorrow.’

‘I would never have called you if I’d thought there was an alternative but …’

From what she remembered of Furst, that much was true. ‘What is it?’

‘I can’t say,’ he whispered. ‘Not over the phone.’

‘Can it wait?’

The pause undermined the lie that followed. ‘For two or three days, maybe.’

Stephanie pictured Furst; a small man with a crooked frame and surprisingly large hands. Miriam, his wife, was taller and broader.

‘Tell me this: is it the same as last time?’

His reply was barely audible: ‘Almost.’

Almost?

She said, ‘I can’t promise you anything.’

‘Will you try?’

No. Instinctively, that was what she felt. Petra hated situations like this. Unsolicited, unprepared. But there would be no easy escape here. There was a barrier in the way constructed of obligation and sentimentality.

‘One o’clock. If I’m not there by half-past, I’m not coming. Shall I come to your home?’

‘No.’

‘Where?’

‘The place we first met. Do you remember it?’

Day Two (#ulink_edb887d6-9d8c-58c5-b503-5730636bf62c)

My carriage is almostempty on the Thalys train service from Brussels-Midi to Gare du Nord in Paris. Belgian countryside scrolls smoothly across my window at high speed, flat and brown beneath a grey sky, ploughed fields speckled with small woods and copses. The tops of the electricity pylons are lost in low, rolling cloud.

A woman in a dark red uniform pours me more coffee. In an hour I’ll be in Paris. In four, I’ll be hurtling through this same stretch of countryside in the opposite direction. In twelve, I’ll be at thirty-five thousand feet, heading for the Indian Ocean.

I’m not sure what I can achieve while I’m with Jacob Furst but I’ll manage something. Furst is a man with a fierce sense of honour; the kind of man to squirm under obligation. And he will feel obligated towards me, no matter how hard I try to persuade him not to be. The truth is, my debt of obligation is greater.

For almost sixty years Furst was one of the great document forgers. A gifted painter from childhood, he was faking masterpieces for wealthy clients by the time he was twenty. At the outbreak of the Second World War, he turned his talents to a more practical purpose, forging documents to help Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. Later, he joined the Resistance, creating papers for SOE agents dropped into France between 1942 and 1943, before his eventual capture. He survived for two years at Auschwitz. After the war, he developed the trade in forged documents for profit, protected by the legitimate screen of the family garment business.

He retired from his art – art being exactly what he considers it – in 1995 when the arthritis in his fingers began to affect the quality of his work. Over the years, Furst passed on his expertise to a small handful of apprentices. One of them was an Irish art student who was studying in Paris during the 1960s. His name was Cyril Bradfield.

Cyril has been creating independent identities for me as long as I’ve been Petra Reuter. In that sense he knows me better than any person alive. In the perverse way that logic works in my world, it seems appropriate that he’s the closest thing I have to a parent; after all, he’s fathered so many of me.

Cyril feels for Jacob Furst the way I feel for him. Which is why the only time he’s ever asked me for help was when it was on Furst’s behalf. It wasn’t a complicated situation, just undignified; an elderly man and his wife threatened by a crooked landlord and his troop of Neanderthal thugs.

That was four years ago and it was the only time I spent with Jacob and Miriam Furst. But we formed a bond. A bond that feels as strong today as it did then. It’s no exaggeration to say this: without Furst, there would have been no Cyril Bradfield for me, and without some of his documents, I’d probably be dead. But the reason I’m going to Paris is that I liked Furst. If I think of Cyril as a surrogate father it’s easy to think of Jacob and Miriam as surrogate grandparents. With some people, you don’t need time to make the connection; it just happens. Often, when you least expect it.

Twelve-fifty, boulevard de Sébastopol in Sentier. Stephanie dropped euro coins into the driver’s palm and climbed out of the taxi. Despite the hard rain, she wanted to walk the last bit. She entered rue Saint Denis from rue Réaumur and it was how she remembered it; clothes shops and garment wholesalers along either pavement, the road itself a narrow artery clogged by double-parked vans, their back doors open, rolls of fabric stacked for delivery. And noise everywhere; bleating horns, music, the rain, half a dozen shouted languages. At the intersection with rue du Caire a dozen Indian and Bangladeshi porters were loitering with trolleys, waiting to be summoned. In the doorways and alleys were the whores; oblivious to the weather, the wrong side of forty, sagging breasts and bloody make-up done no favours by the dismal daylight.

Stephanie entered Passage du Caire, an arcade of cramped passages with filthy glass overhead, and came to the place where the Fursts’ family business had once been. Part of the sign still hung above the door, the red plastic letters faded to dirty pink. The window was crammed with mannequins; beige females with no heads or arms. A piece of paper pasted to the glass offered fifty percent discounts for bulk orders.

Four doors down was La Béatrice, the kosher café where Cyril Bradfield had introduced Stephanie to Jacob Furst. Seven tables with magnolia Formica tops, a selection of snacks laid out behind a glass counter, fluorescent tubes taped to sagging ceiling panels, one of them hanging loose. On the wall beside the espresso machine was a large wooden framed photograph of George Clooney next to a smaller frame containing a certificate bearing the words ‘Shin Beth de Paris’.

There were half a dozen people in the place. Mostly from the arcade, she guessed; none of them were wet. Stephanie recognized Béatrice, a haughty-looking woman with dyed black hair. She ordered a cappuccino and took it to a vacant table by the small circular staircase leading to the upper floor. Béatrice fiddled with the portable radio on the counter until Liane Foly was singing ‘Doucement’. In the café’s wet warmth, Stephanie caught a whiff of cinnamon.

One o’clock came and went. So did Béatrice’s customers. Stephanie noticed a man who seemed vaguely familiar; slim, tall, well dressed, in his fifties with the same dark blonde hair she’d had as Krista Jaspersen. He was sitting at a table near the staircase. She couldn’t pin a name to the face but wondered whether she might have seen him on TV.

At one-fifteen her mobile rang.

‘Petra?’

‘Jacob?’

‘Where are you?’

The high-pitched voice sounded more tremulous than usual.

‘I’m where you should be. Unless my memory’s going.’

He didn’t reply straight away and she regretted her sarcasm.

‘I apologize, Petra.’

‘Where are you? I don’t have long, Jacob.’

‘Fifteen minutes, okay?’

‘Okay.’

‘You’ll stay?’

‘Of course.’

‘Good. Two minutes, then …’

He finished the call and Stephanie sat there for a moment trying to remember something she’d forgotten. Something she’d intended to ask him. Something that had come back to her on the train.

The phone. The number. How had Furst got Marianne’s number? And now that she thought about that, there was something else. Fifteen minutes? Or two?

She found she was reaching into her coat pocket for loose change; as usual, Petra was ahead of Stephanie, her instinct taking over. There were no coins left. The last of them had gone to the taxi driver. She put a ten-euro note beneath the saucer and stood up.

Out in the passage she looked both ways. Nothing. She decided to wait for his call somewhere nearby. When he arrived and discovered that she’d left, he’d phone again. She was certain of it.

She turned back towards the rue Saint Denis entrance.

And was airborne.

The shockwave was the sound somehow. A flash. Light, heat, no air in her lungs. She was aloft in a hurricane of debris. Then gravity reclaimed her and she was smeared across … what, exactly?

Darkness followed. Unconsciousness? Or just darkness?

The screams began. Cutting through the hum in her head. When she opened her eyes she couldn’t see. A cloud of dust enveloped her, as impenetrable as highland mist. She didn’t know if she was injured because she was numb. But she was aware of wetness down her back. And dirt in her mouth. There was a smell too; something cloying. Burning plastic, perhaps?

Her foot was trapped, wedged between two solid shapes.

She closed her eyes. Time to sleep.

No.

Petra twisted her body so that she could see her right foot. A grey filing cabinet was on top of it, two of its three drawers blown out. Beneath it was half a beige mannequin. She used her left foot against the filing cabinet, creating a gap for the right, then rolled off her mattress of fractured dummies.

Water droplets splashed on her face. A burst pipe. Or rain. She looked up but saw only smoke and dust.

The right ankle was tender. She hauled herself to her feet. Nausea rose up inside her. One step, then another. For now, that was enough. Adrenaline, her most faithful servant, would see her through.

In the remains of the passage fires sprouted in the gloom, deep orange and gold. A severed cable spat white hot sparks over a soggy roll of material with a floral print. Except it wasn’t a roll. It was a body in a dress. Petra made out an arm, filthy black, the hand crushed to pulp.

The passage had a lawn of broken glass. Not just from store windows but from the canopy overhead; metres and metres of it reduced to splinters.

La Béatrice was burning rubble. How many people had been inside? Half a dozen? Maybe. The upper floor had collapsed into the café. She didn’t know whether there had been anyone up there. Scorched body parts hung from the fractured iron staircase. At the foot of the stairs, Béatrice’s head and upper torso were on fire. Petra couldn’t see the rest of the corpse but could smell her burning hair. Closer to the entrance, a single boot and shin protruded from beneath a concrete slab. Less than a metre away, blood was oozing through cracked brick.

There was music. Weak, muffled, rising up from beneath the debris; Béatrice’s portable radio, still working, no matter how improbably. Petra looked to her right. Rue Saint Denis had gone, concealed by the cloak of smoke.

She began to cough, lining her nostrils and mouth with dust. Stunned, all her training suspended, she staggered away, each step as uncertain as the one before. A few metres on, a pretty blonde woman in a lilac cardigan and brown tweed skirt lay on the ground, twitching, flayed by glass.

Under the screams she heard distant shouts; people making their way towards the carnage. Boots scrambled over loose brick, muttered curses followed falls.

To her left, a large fire was taking hold, glass cracking in the heat. She came to a fork in the passage. Over the ringing in her head an orchestra of alarms grew louder. She veered right, then stopped.

‘… to be careful, okay?’

A snatch of conversation coming her way. Then another voice: ‘Check everywhere.’

‘… watch overhead for collapsing …’

Shapes were forming in the murk.

‘… somewhere in here … keep looking …’

‘… extremely dangerous … and armed …’

Two figures, certainly, perhaps three.

‘… take any chances …’

Petra coughed again, spitting out brown saliva.

The first figure emerged from the dust, a light grey raincoat billowing around him. The next was in uniform. An armed police officer with a full moustache. Other silhouettes took shape behind them.

The first man saw her, halted abruptly, then pointed directly at her. ‘Shit! It’s her! There she is!’

There who is?

Who was he looking at? Why was he pointing at her?

A third figure was forming, another armed officer in uniform, then a fourth man in a tan leather coat.

‘Shoot her.’

A mistake, clearly. Except Petra knew that it wasn’t.

The first armed officer looked unsure.

‘It’s her,’ barked the man in the grey raincoat. ‘I tell you, it’s her!’

‘I don’t see the …’

‘She’s armed! Now shoot her!’

The man in the leather coat was already raising his right hand. The second officer was pushing past the first. And Petra was moving, taking the passage directly ahead, already aware of the fact that it was too straight. In a matter of seconds, before she could melt into the smoke, they would have a clear view of her back.

Behind her now, the same voice again. ‘Henri! Watch out! She’s coming your way! She’s got a gun …’

What gun?

Movement grew in the dimness ahead. Petra entered the smoking remains of a boutique; retro-punk T-shirts, studded leather mini-skirts, frayed tartan hot-pants, a severed hand with a silver thumb-ring. She dragged a sloping chunk of partition wall from across the doorway at the back.

‘Shit – Didi, you asshole! I nearly shot you! Where is she?’

More coughing. ‘I don’t know. Maybe you passed her …’

‘In there!’ cried a third voice. ‘Look!’

There was a single shot as Petra plunged into more darkness. She felt the thud of a bullet hitting a panel of MDF to her left. She came to a shoulder-wide passage with stairs to her right. Up to the first floor, a cramped storage area, the ceiling less than a foot taller than she was. The blast had blown the glass from the internal window overlooking the passage. She could hear them arguing below.

No weapon. No way out.

Except for the window. She approached the hole cautiously. Just above her was a web of iron struts, pipes and rubber cable, all of it ancient. Through the dust-haze she watched the four men beneath her. They were looking into the blackened shell of the boutique, shouting at those who’d followed her inside.

No choice, so no need to think about it. Up on to the sill and out on to the ledge, the remaining fragments of glass in the window-frame nibbling the palms of her right hand. There was a rusting water-pipe above her head. She gave it a quick tug; it seemed secure. She held on to it and swung, her toes catching the corner of a sturdy junction box, one of six bolted to a panel, cables spewing from them like black spaghetti.

‘Up there!’ bellowed a man below. ‘Quick!’

But not quick enough. She was already over the ledge above, propelling her body through a mesh of twisted metal ribs. On the roof, she gauged the way the passages worked, the ridges, the intersections. Most of the glass had gone. To her left, thick black smoke was curling skywards, the flames beneath undeterred by the rain.

It was slippery underfoot, years of grime given gloss by the downpour. She tried to work out where rue Saint Denis was so that she could head in the opposite direction. It wasn’t obvious from the backs of the surrounding buildings but there was a gap so she headed for that. The roof tapered to a short stretch of crumbling wall that abutted a taller building; apartments from the first floor up, a business at street level, the shutters pulled down over the windows.

She took the drainpipe to the first floor, swiping three potted plants from a window-ledge, then lowered herself on to the roof of a white Renault Mégane that was parked on the pavement.

Now she was in a small triangular square: rue Saint Spire, rue Alexandrie, rue Sainte Foy. She took Sainte Foy.

Five-past-two, the sirens now a long way behind her. She was still walking, the rain still falling. And helping. Under the circumstances, better to be drenched than dirty. Which was all the logic she could handle.

Head for Gare du Nord. Use the return ticket. Go home, have a shower, catch the plane. Worry about it over a cocktail on the beach.

She was sorely tempted yet knew she couldn’t. Stations were out. So was home. Which meant Marianne Bernard’s integrity was suspended. And it was Marianne’s name on the air ticket.

How had the police got there so quickly? How had they identified her so quickly? And the order to shoot – because she was armed – what did that mean?

One part of her wanted to stop and think. To collate. But another part of her wouldn’t let her. She had to keep moving. That was the priority.

Never stop. The moment you do …

Three-thirty-five. The cinema provided a temporary sanctuary of darkness. The film was a Hollywood romantic comedy, predictably short on romance, utterly devoid of comedy. Stephanie waited until the main feature had started before going to the washroom. She peeled off her denim jacket and the black polo-neck. Both were soaked. The long-sleeved strawberry T-shirt beneath was stuck to her skin. She filled a basin with warm soapy water, rolled up the sleeves to the elbow, scrubbed her face, hands and arms, rinsed, refilled the basin with clean warm water and dipped her head into it, before trying to claw some order through her hair.

A little cleaner but still dripping, she locked herself into one of the stalls, hanging the jersey and jacket on the door-peg. She lifted the T-shirt, examined her torso and ran her fingertips over as much of her back as she could. Nothing but a few cuts and grazes. She pulled down the toilet lid, sat on it, pulled off a dark grey Merrell shoe and checked the right ankle; swollen, tender to the touch, but no significant damage. When she envisaged Béatrice it seemed little short of a miracle. And all because of Petra; Stephanie would have stayed at the table for Jacob Furst.

She pulled on her wet clothes and checked her possessions; the return portion of her train ticket, Marianne’s credit-cards, a Belgian driving licence, flat keys, six hundred and seventeen euros in cash, mobile phone, cinema ticket.

Stephanie returned to the comforting dark of the auditorium, taking a seat near the back, and was grateful for the stuffy warmth. First things first, a plan of action. The primary urge was to run. And she would run. As she had in the past. That was the easy part. Nobody ran as effortlessly as Petra. But she couldn’t allow fear to be the fuel. Before that, however, there were questions.

She rose into the ethnic melting-pot of Belleville. The pavement along the eastern flank of the broad boulevard de Belleville was busy. Stephanie weaved through Afghans, Turks, Iranians, Georgians, Chinese. A group of five tall Sudanese were arguing on the corner of rue Ramponeau. A Vietnamese woman barged past her dragging a bulging laundry bag. Traffic was stationary in both directions, frustrated drivers leaning on their horns.

Stephanie switched on her mobile. No messages and no missed calls since she’d turned it off twenty minutes after clearing Passage du Caire. She return-dialled Jacob Furst’s number. No answer. She switched the phone off again and walked up rue Lémon to rue Dénoyez. The five-storey building was on the other side of the road. At street level, the Boucherie Shalom was closed. The restaurant next to it was open but Stephanie couldn’t see any diners through the window.

The Fursts’ apartment was on the third floor. No lights on, the curtains open. There were weeds sprouting from the plaster close to a fracture in the drainpipe. There was no building to the right. It had been demolished, the waste ground screened from the street by a barricade of blue and green corrugated iron.

She ventured left, away from the building, heading up the cobbled street past graffiti and peeling bill posters, past the entrance to the seedy Hotel Dénoyez – rooms by the hour – until she came to rue Belleville. Then she made a circle and approached rue Dénoyez from the other end at rue Ramponeau.

The Furst family had a Parisian lineage stretching back two centuries. In that time, there had been two constants: a family business centred on the garment industry and active participation within the Jewish community. Which included living among that community. And here was the proof. On rue Ramponeau, Stephanie stood with her back to La Maison du Taleth, a shop selling Jewish religious artefacts. Restaurants and sandwich shops all displayed with prominence the Star of David.

She returned to boulevard de Belleville. From the France Télécom phonebooth by the Métro exit she rang the police. An incident to report, some kind of break-in, she told them. She’d heard noises – screams for help, breaking glass, a loud bang – and now nothing. Please hurry – they’re an old couple. Vulnerable …

When they’d asked for her name, she put down the phone.

She watched from the bright blue entrance to Hotel Dénoyez. When the patrol car pulled up a pair of officers emerged and she noticed two things. First, they looked casual; from the way they moved she guessed they were expecting an exaggerated domestic disturbance. Or a hoax. The second thing was the dark blue BMW 5-series halfway between her and the patrol car.

It had been there as long as she’d been loitering by the hotel entrance. She’d assumed there was no one in it. But when the patrol car pulled up, the BMW’s engine coughed, ejecting a squirt of oily smoke from the exhaust. She peered more carefully through the back window and now saw that there were two people inside. The car didn’t move until the police officers had entered the building. Then it pulled away from the kerb, tyres squeaking on the cobbles, turning right at rue Ramponeau.

She continued to wait. A third-floor light came on. Stephanie pictured Miriam Furst in the kitchen at the rear of the flat. Making coffee for the policemen, taking mugs from the wooden rack above the sink. That was how she remembered it. Beside the rack, a cheap watercolour of place des Vosges hung next to a cork noticeboard with family photographs pinned to it: three children, all girls, and nine grandchildren, none of whom had been inclined to steer the Furst textile business into its third century.

Fifteen minutes after the arrival of the first police car, a second arrived. Followed within forty-five seconds by an ambulance, then a third police car and, finally, a second ambulance. Three policemen began to cordon off the street.

Now it was no longer just Stephanie’s fingers that were going numb.

We pull into Tuileries, in the direction of La Défense. I’ll probably change at Franklin D. Roosevelt and head for Mairie de Montreuil, then change again after a dozen stations or so. It’s five-to-eleven and I’ve been riding the Métro for more than two hours. There’s no better way to make yourself invisible for a short while than to ride public transport in a major city late at night. Later, they’ll see me on CCTV recordings, drifting back and forth. But by then I’ll be somewhere else. And someone else.

Above ground, in the bars and restaurants, in private homes, there is only one topic of discussion tonight. The bomb blast in Sentier. Many dead, many wounded, many theories. There’ll be grief and outrage on the news, and plenty of inaccurate in-depth analysis from the experts.

I know that Jacob and Miriam Furst are dead. Nobody will read about them tomorrow. They will have died largely as they lived; unnoticed. I also know that I should be dead too.

The men who chased me through the smoking wreckage in Passage du Caire were there to make sure. They were there so quickly. And they weren’t looking for anyone else; they recognized me.

I try to fix a version of events in my head. Furst is held against his will until he’s made the call to establish that I’m in place. He’s surprised that I’m there. Did he think I wouldn’t come? He tells me he’ll be with me in fifteen minutes, then two. Why the difference? To arouse my suspicion? To warn me?

How did he get the number? And why wasn’t I more vigilant? Perhaps, mentally, I was already halfway to Mauritius.

After our conversation is over, the explosion occurs within a minute. But the more I consider it, the more perplexing it becomes. They – whoever ‘they’ are – needed to be sure that I’d be in Paris today. That I’d be in La Béatrice at one o’clock. How could they be confident that I’d make the trip from Brussels? And if I’m to assume that they knew I was in Brussels, which as a matter of security I must, shouldn’t I also assume that they know I’m Marianne Bernard? And if they know that, where does the line of enquiry stop? Whether they knew about Marianne Bernard or not, it’s obvious who they really wanted. Petra Reuter. She’s the one with the reputation.

So why the elaborate deceit? Nobody who knew anything about her would risk that. They’d take her down the moment they found her. At home, for instance, in a run-down apartment in Brussels. They’d catch her with her guard down. Simpler, safer, better.

There can be only one answer: they needed me to be at La Béatrice.

Day Three (#ulink_5a84cf8e-ed37-5193-9752-f2dcb0348959)

The Marais, quarter-past-five in the morning, the streetlamps reflected in puddles not quite frozen. Rue des Rosiers was almost empty; one or two on the way home, one or two on the way to work, hands in pockets, chins tucked into scarves.

It had been after midnight when she abandoned the Métro. Since then, she’d stopped only once, when the rain had returned just before three. She’d found an all-night café not far from where she was now; candlelight and neon over concrete walls, leather booths in dark corners, Ute Lemper playing softly over the sound system.

Stephanie stretched a cup of black coffee over an hour before anyone approached her. A tall, angular woman with deathly pale skin and dark red shoulder-length hair, wearing a purple silk shirt beneath a black leather overcoat. She smiled through a slash of magenta lipstick and sat down opposite Stephanie.

‘Hello. I’m Véronique.’

Véronique from Lyon. She’d been awkwardly beautiful once – perhaps not too long ago – but thinness had aged her. And so had unhappiness. Stephanie warmed to her because she understood the chilly solitude of being alone in a city of millions.

They talked for a while before Véronique reached for Stephanie’s hand. ‘I live close. Do you want to come? We could have a drink?’

Petra considered the offer clinically: Véronique was an ideal way to vanish from the street. No security cameras, no registration, no witnesses. Inside her home, Petra would have options; some brutal, some less so. But it was after four; there was no longer any pressing need for a Véronique.

Stephanie let her down gently with a version of the truth. ‘It’s too late for me. If only we’d met earlier.’

She turned left into rue Vieille du Temple. The shop was a little way down, the red and gold sign over the property picked out by three small lamps: Adler. And beneath that: boulangerie – patisserie.

Stephanie knocked on the door. Behind the glass a full-length blind had been lowered, fermé painted across it. A minute passed. Nothing. She tried again – still nothing – and was preparing for a third rap when she heard the approach of footsteps and a stream of invective.

The same height as Stephanie, he wore a creased pistachio shirt rolled up at the sleeves and a black waistcoat, unfastened. A crooked nose, a mash of scar around the left eye, thick black hair everywhere, except on his head. The last time, he’d had a ponytail. Not any more, the close crop a better cut to partner his encroaching baldness. There was a lot of gold; identity bracelets, a watch, chains with charms, a thick ring through the left ear-lobe. As Cyril Bradfield had once said to her, ‘He looks like the hardest man you’ve ever seen. And dresses like a tart.’

‘Hello, Claude.’

Claude Adler was too startled to reply.

‘I knew you’d be up,’ Stephanie said. ‘Four-thirty, every day. Right?’

‘Petra …’

‘I would’ve called, of course …’

‘Of course.’

‘But I couldn’t.’

‘This is … well … unexpected?’

‘For both of us. We need to talk.’

It was delightfully warm inside. Adler locked the door behind them and they walked through the shop, the shelves and wicker baskets still empty. The cramped bakery was at the back. Stephanie smelt it before she saw it; baguettes, sesame seed bagels, apple strudel, all freshly prepared, all of it reminding her that she hadn’t eaten anything since Brussels.

Adler took her upstairs to the apartment over the shop where he and his wife had lived for almost twenty years. He lit a gas ring for a pan of water and scooped ground coffee into a cafetière. There was a soft pack of Gauloises on the window-ledge. He tapped one out of the tear, offered it to her, then slipped it between his lips when she declined.

‘Is Sylvie here?’

‘Still asleep.’ He bent down to the ring of blue flame, nudging the cigarette tip into it, shreds of loose tobacco flaring bright orange. ‘She’ll be happy to see you when she gets up.’

‘I doubt it. That’s the reason I’m here, Claude. I’ve got bad news.’

Adler took his time standing. ‘Have you seen the TV? It seems to be the day for bad news.’

‘It is. Jacob and Miriam are dead.’

He froze. ‘Both?’

Stephanie nodded.

At their age, one was to be expected. Followed soon after, perhaps, by the other. But both together?

‘When?’

‘Last night.’

‘How?’

‘Violently.’

He began to shake his head gently. ‘It can’t be true.’

‘It is true.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I saw the police. The ambulances …’

‘You were there?’

‘Afterwards, yes.’

‘Did you see them?’

Stephanie shook her head.

‘Then perhaps …’

‘Trust me, Claude. They’re dead.’

He wanted to protest but couldn’t because he believed her. Even though she hadn’t seen the bodies. Even though he didn’t know her well enough to know what she did. Not exactly, anyway.

‘Who did it?’

‘I don’t know.’

He thought about that for a while. ‘So why are you here?’

‘Because I’m supposed to be dead too.’

Adler refilled their cups; hot milk first, then coffee like crude oil, introduced over the back of a spoon, a ritual repeated many times daily. Like lighting a cigarette. Which he now did for the fourth time since her arrival, the crushed stubs gathering on a pale yellow saucer.

Now that he’d absorbed the initial shock, Adler was reminiscing. Secondhand history, as related to him by Furst: the pipeline pumping Jewish refugees to safety; the false document factory he’d established in Montmartre; 14 June 1940, the day the Nazis occupied Paris; smuggling Miriam to Lisbon via Spain in the autumn of 1941; forging documents for the Resistance and then SOE. And finally, betrayal, interrogation, Auschwitz.

Adler scratched a jaw of stubble, some black, some silver. ‘He always said he was lucky to live. Listening to him tell it, I was never so sure.’ He stirred sugar into his coffee. ‘You survive something like that, the least you expect is to be left alone to die of natural causes. Fuck it, he was nearly ninety.’

‘You’re right.’

‘You know what I admired most about him?’

‘What?’

He drew on his cigarette and then exhaled over the tip. ‘That it never occurred to him to leave. From 1939 on, he could’ve run. But he didn’t. He chose to stay behind, to create false documents to help others escape. He knew the risks better than most. Yet even when they got Miriam out, it never crossed his mind to go with her.’