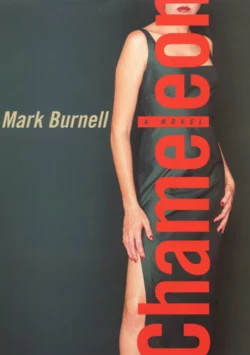

Chameleon

Mark Burnell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Триллеры

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1241.23 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: They are chameleons. Beyond the law, beyond morality, they’ve survived by adapting, whatever the circumstances. And by trusting nobody but themselves.IT’S A QUESTION OF IDENTITY.Stephanie Patrick, a woman who was more comfortable under an alias than she was with hersef, she traversed the world and forgot who she was. Now, she wants to put all her pasts behind her.Konstantin Komarov. The FBI call him the Don from the Don. Today, at the heart of a financial empire created by the Russian crime pandemic, he’s as comfortable in Manhattan as he is in Moscow or Magadan.Between them exists Koba, an old alias for a new threat.In a world where trust is weakness, honesty is naivety, brutality is routine, could falling in love be the greatest risk?