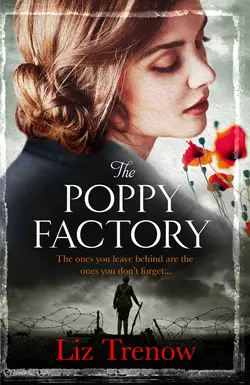

The Poppy Factory

Лиз Тренау

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A captivating story of two young women, bound together by the tragedy of two very different wars. Perfect for fans of Katie Flynn and Maureen Lee.With the end of the First World War, Rose is looking forward to welcoming home her beloved husband, Alfie, from the battlefields. But his return is not what Rose had expected. Traumatised by what he has seen, the Alfie who comes home is a different man to the one Rose married. As he struggles to cope with life in peacetime, Rose wrestles with temptation as the man she fell in love with seems lost forever.Many years later, Jess returns from her final tour of Afghanistan. Haunted by nightmares from her time at the front, her longed-for homecoming is a disaster and she wonders if her life will ever be the same again. Can comfort come through her great-grandmother Rose’s diaries?For Jess and Rose, the realities of war have terrible consequences. Can the Poppy Factory, set up to help injured soldiers, rescue them both from the heartache of war?