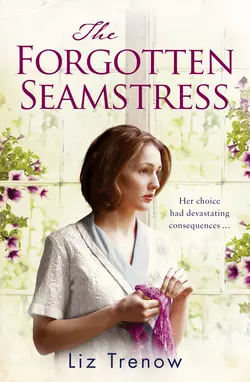

The Forgotten Seamstress

Liz Trenow

When Caroline Meadows discovers a beautiful quilt in her mother’s attic, she sets out on a journey to discover who made it, and the meaning of the mysterious message embroidered into its lining.Many years earlier, before the first world war has cast its shadow, Maria, a talented seamstress from the East End of London, is employed to work for the royal family. A young and attractive girl, she soon catches the eye of the Prince of Wales and she in turn is captivated by his glamour and intensity.But careless talk causes trouble and soon Maria’s life takes a far darker turn.Can Caroline piece together a secret history and reveal the truth behind what happened to Maria?

LIZ TRENOW

The Forgotten Seamstress

Copyright

AVON

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

Copyright © Liz Trenow 2013

Liz Trenow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007480845

Ebook Edition © December 2013 ISBN: 9780007480852

Version: 2014-07-25

Dedication

To David who has, as ever, been a constant source of love and support.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u0e31f0a5-a7f9-5df1-ac3a-758f4d2e006f)

Title Page (#u5f3c06a2-c7ba-5341-bb99-4eb26cd1bfa8)

Copyright (#ubb73fa71-5930-5578-ab24-f355e16ed6fe)

Dedication (#ufeaf518e-cf5c-5880-a3bf-cb7accba2213)

Chapter One (#u4434fa72-52c7-57a2-a722-3111897e38b4)

Chapter Two (#u2310fbc9-6606-5579-8277-848a0c5680f4)

Chapter Three (#ud9ac5f8a-b26b-54df-be98-53b343baca94)

Chapter Four (#u5ac2a607-812a-581d-b72d-67e4303dbef8)

Chapter Five (#uff6d0e33-21f0-5001-aae7-ed551e96a560)

Chapter Six (#ub030d365-2374-5938-9628-d9fd9e8fc21f)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Book Club Q&A for The Forgotten Seamstress, by Liz Trenow (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Liz Trenow (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Patchwork (noun):

1 Work consisting of pieces of cloth of various colours and shapes sewn together.

2 Something composed of miscellaneous or incongruous parts.

Quilt (verb):

1 To fill, pad or line (something) like a quilt.

2 To stitch, sew or cover (something) with lines or patterns resembling those used in quilts.

3 To fasten layers of fabric and/or padding in this way.

From the Medical Superintendent

Helena Hall, 2nd April 1970

Dear Dr Meadows

Thank you for your letter in reference to your student Patricia Morton. We are always keen to support the work of bona fide research projects, and will certainly endeavour to provide her with the contacts and other information that she seeks.

However, before giving permission we would like your personal written confirmation that she will observe the following:

All interviews must be carried out anonymously, and no information which might identify the patient or staff member must appear in the final publication.

No patient may be interviewed without their prior informed consent, supported by their psychiatric consultant and, where appropriate, a key family member.

Any member of staff must seek the prior written consent of their senior manager.

In regards to former staff members and patients, Eastchester Mental Health Service has no jurisdiction, but we would seek your reassurance that Ms Morton will observe the same conditions of confidentiality as above. I am sure she will appreciate that, in terms of research data, existing and former patients may not be the most reliable of informants. Most, if not all, will have suffered from lifelong illnesses which may lead them to hold beliefs and opinions which have no actuality or validity in real life.

You will understand that while patient confidentiality precludes us from giving information about individuals, I would be grateful for the opportunity to provide Ms Morton with guidance in relation to specific interviewees. Please ask her to contact my secretary on the number above, to arrange an appointment at the earliest possible opportunity.

With kindest regards

Dr John Watts, Medical Superintendent,

Helena Hall Hospital, Eastchester

Chapter One

Cassette 1, side 1, April 1970

They told me you want to know my story, why I ended up in this place? Well, there’s a rum question and I’ve been asking it meself for the past fifty years. I can tell you how I got here, and what happened to me. But why? Now that’s a mystery.

It’s a deep, smoke-filled voice, with a strong East London accent, and you can hear the smile in it, as if she’s about to break into an asthmatic chuckle at any moment.

They’ve probably warned you about me, told you my story is all made up. At least that’s what those trick-cyclists would have you believe.

Another voice, with the carefully-modulated, well-educated tones of a younger woman: ‘Trick-cyclist?’

Sorry, dearie, it’s what we used to call the psychiatrist, in them old days. Any roads, he used to say that telling tales – he calls them fantasies – is a response to some ‘ungratified need’.

‘You’re not wrong there,’ I’d tell him, giving him the old eyelash flutter. ‘I’ve been stuck in here most of me life, I’ve got plenty of ungratified needs.’ But he’d just smile and say, ‘You need to concentrate on getting better, my dear, look forward, not backwards all the time. Repeating and reinforcing these fantasies is just regressive behaviour, and it really must stop, or we’ll never get you out of here.’

Well, you can take it or leave it, dearie, but I have to tell it.

‘And I would very much like to hear it, that’s what I’m here for.’

That’s very kind of you, my dear. You see, when you’ve been hidden away from real life for so many years, what else is there to do but remember the times when you were young, when you were meeting new people every day, when you were allowed to have feelings, when you were alive? Nothing. Except for me needlework and other creations, they were the only things that would give me a bit of comfort. So I tell my story to anyone who will listen and I don’t care if they call me a fantasist. Remembering him, and the child I lost, is the only way I could hold onto reality.

So, where do you want me to start?

‘At the beginning would be fine. The tape is running now.’

You’ll have to bear with me, dearie, it’ll take some remembering, it was that long ago. I turned seventy-four this year so the old brain cells are not what they used to be. Still, I’ll give it a try. You don’t mind if I carry on with me sewing while I talk, do you? It helps me concentrate and relax. I’m never happy without a needle in my fingers. It’s just a bit of appliqué with a button-hole stitch – quite straightforward. Stops the fabric fraying, you see?

She is caught by a spasm of coughing, a deep, rattling smoker’s cough.

Hrrrm. That’s better. Okay, here we go then.

My name is Maria Romano and I believe my mother was originally from Rome, though what she was doing leaving that beautiful sunny place for the dreary old East End of London is a mystery. Do they all grow small, the people who live in Italy? Mum was tiny, so they said, and I’ve never been more than five foot at the best of times. These days I’ve probably shrunk to less. If you’re that size you don’t have a cat’s chance of winning a fight so you learn to be quick on your feet – that’s me. I used to love dancing whenever I had the chance, which wasn’t often, and I could run like the wind. But there have been some things in my life even I couldn’t run away from – this place being one of them.

The strange thing is that, after all those years of longing to get out, once we was allowed to do what we liked, we always wanted to come back – it felt safe and my friends were here. It was my home. When they started talking about sending us all away to live in houses it made me frightened just to imagine it, and if it was worrying me, what must it have been like for the real crazies? How do they ever cope outside? You’re a socio-wotsit, aren’t you? What do you think?

‘I’m happy to talk about that later, if you like, but we’re here to talk about you. So, please carry on.’

I will if you insist, though I can’t for the life of me imagine what you find so interesting in a little old lady. What was I talking about?

‘Your mother?’

Ah yes, me poor mum. Another reason to believe she was Italian is my colouring. I’m all grey now, faded to nothing, but my skin used to go so dark in summer they said I must have a touch of the tar brush, and my shiny black curls were the envy of all the girls at the orphanage. Nora told me the boys thought I was quite a looker, and I learned to flash my big brown eyes at them to make them blush and to watch their glances slip sideways.

‘The orphanage?’

Ah yes, Mum died when I was just a babe, only about two years old I was, poor little mite. Not sure what she died of, but there was all kinds of diseases back then in them poor parts of the city, and no doctors to speak of, not for our kind at least. They hadn’t come up with antibiotics or vaccinations, nothing like that – hard to believe now, but I’m talking about the really old days, turn of the century times.

After he’d had his fun, my father disappeared off the scene as far as I knew, and I never heard tell of any grandparent, so when she died I ended up at The Castle – well, that’s what we called it because the place was so huge and gloomy and it had pointy windows and those whatchamacall-ums, them zigzaggy patterns around the top of the walls where the roof should be.

‘Castellations?’

It was certainly a fortress, with high iron gates and brick walls all around. To keep dangerous people out, they told us – this was the East End of London after all – but we knew it was really to stop us lot running away. There was no gardens as such, no trees or flowers, just a paved yard we could play in when the weather was good.

Inside was all dark wood and stone floors, and great wide stairways reaching up three or four storeys; to my little legs it felt like we was climbing up to heaven each time we went to bed. It sounds a bit tragic when I tell it, but I don’t remember ever feeling unhappy there. I knew no different, it was warm and the food was good, and I had plenty of company – some of them became true friends.

The nuns was terrifying to us littl’uns at first, in their long black tunics with sleeves that flared out like bats’ wings when they ran along the corridors chasing and chastising us. Most of ’em was kindly even though some could get crotchety at times. No surprise really, with no men in their lives, and just a load of naughty children.

It was a better start in life than I’d have had with my poor mum, I’ll warrant. Pity it didn’t turn out like that in the end.

Anyway, the nuns’ sole aim in life was to teach us little monsters good manners and basic reading and writing, as well as skills like cooking, housework and needlework so we could go into service when we came of an age, which is exactly what happened to me. I ’specially loved needlework. I was good at it, and I loved the attention it give me.

‘It’s a gift from God,’ the nuns would say, but I didn’t believe that. It was just ’cos I had tiny fingers, and I took more trouble than the others, and learned to do it properly. We had all the time in the world, after all.

D’you do any sewing, Miss?

‘Not really, I’m more of a words person.’

You should give it a try. There’s nothing more satisfying than starting with a plain old piece of wool blanket that no one else wants and ending up with a beautiful coat that’ll keep a child warm through many a winter. Or to quilt up scraps of cotton patchwork to make a comfy bedcover that ain’t scratchy and makes the room look pretty besides.

The needlework room at The Castle had long cutting tables and tall windows set so high you couldn’t see out of them, and that was where we spent most of our days. In winter we’d huddle by the old stove in the corner, in summer we’d spread out round the room in gaggles so that we could gossip away from those nuns’ ears, which was sharp as pins.

It was all hand-stitching, mind, no sewing machines in those days of course. And by the time I was ten I knew which needle to use with which fabrics and which kind of thread, and I could do a dozen types of stitch, from simple running stitch and back stitch, to fancy embroidery like wheatear and French knots, and I loved to do them as perfect and even as possible so you could hardly tell a human hand had made them. Sister Mary was a good teacher and loved her subject, and I suppose she passed her enthusiasm on to us, so before long I could name any fabric with my eyes closed, just by the feel, tell the difference between crêpe and cambric, galatea and gingham, kersey and linsey-woolsey, velvet and velvetine, and which was best for which job.

Not that we saw a lot of fine fabrics, mind, it was mostly plain wool and cotton, much of it second hand what we had to reclaim from used garments and furnishings. But on occasions the local haberdashery would bring rolls of new printed cottons and pattern-weave wools they didn’t want no more, out of charity I suppose for us poor little orphan children, and the other little orphans we was making the clothes for.

You look puzzled? Sorry, I get carried away with me memories. The reason we was so busy sewing at The Castle was because the nuns had been asked by the grand ladies of the London Needlework Society to help them with their good works – which was making clothes for poor people. It made us feel special; we had nothing in the world except our skills, and we were using them to help other children like us.

The days when those haberdashers’ deliveries arrived was like birthdays and Christmases rolled into one: taking the wrappers off the rolls and discovering new colours and patterns, and breathing in that clean, summery smell of new fabric, like washing drying on a line – there’s nothing to match it, even now. When we was growing out of our clothes the nuns would let us have offcuts of patterned cotton to make ourselves new dresses and skirts, and Nora and me would always pick the brightest floral prints. We didn’t see too many flowers for real, so it brought a touch of springtime into our lives.

‘Nora? You knew each other even then?’

Oh yes, we go way back. She was my best friend. We was around the same age so far as we knew, and always shared a dormitory, called ourselves sisters – the family kind, not the nun kind – and swore we’d never be parted. Not that we looked like family by any stretch: she was blonde and by the time we was fourteen she towered above me at five feet six, with big feet she was always tripping over, and a laugh like a tidal wave which made anyone around her – even the nuns – break out into a smile. She had large hands, too, double the size of mine, but that didn’t stop her being a good needleworker. We was naughty little minxes but we got away with it ’cos we worked hard.

Like I say, we was happy because we knew no different, but we was also growing up – even though my chest was flat and my fanny still smooth as a baby’s bottom, Nora was getting breasts and hair down there, as well as under her arms, and both of us was starting to give the eye to the gardener’s lad and the baker’s delivery boy, whenever the nuns weren’t watching.

That day we was doing our needlework when this grand lady with a big hat and feathers on the top of her head comes with a gaggle of her lah-di-dah friends, like a royal visit it was, and she leans over what I am embroidering and says, ‘What fine stitching, my dear, where did you learn that?’

And I says back, ‘It’s daisy chain, Ma’am. Would you like to see how it works?’ And I finish the daisy with three more chain links spaced evenly round the circle like they are supposed to be, and quickly give it a stem and a leaf which doesn’t turn out too bad, even though my fingers are trembling and sweaty with being watched by such a grand person. She keeps silent till I’ve finished and then says in her voice full of plums and a bit foreign, ‘That is very clever, dear, very pretty. Keep up the good work’, and as she moves on to talk to another girl I breathe in the smell of her, like a garden full of roses, what I have never smelled before on a human being.

Afterwards I hears her asking Sister Mary about me and Nora, was we good girls and that sort of thing, but we soon forgot about her and that was it for a few months till my birthday – it was January 1911 when I turned fifteen – and me and Nora, whose birthday was just a few days before, gets a summons from Sister Beatrice, the head nun. This only usually happens when one of us has done something wicked like swearing ‘God’ too many times or falling asleep in prayers, so you can imagine the state that Nora and me are in as we go up the stairs to the long corridor with the red Persian runner and go to stand outside the oak door with those carvings that look like folds of fabric in each panel. I am so panicked that I feel like fainting, and I can tell that Nora is trying to stifle the laugh that always bubbles up when she’s nervous.

Sister calls us in and asks us to sit down on leather-seated chairs that are so high that my legs don’t reach the ground and I have to concentrate hard on not swinging them ’cos I know that annoys grown-ups more than anything else in the world.

She turns to me first. ‘Miss Romano? I think it is your birthday today?’ she asks, and I am so startled at being called ‘Miss’ that I can’t think of anything better to say than, ‘Yes Ma’am.’

‘Then God bless you, child, and let me wish you many happy returns of this day,’ she says, nearly smiling.

‘Thank you, Ma’am,’ I say, trying to ignore the way Nora’s body is shaking beside me.

‘Miss Featherstone?’ says Sister, and I know that if Nora opens her mouth the laugh will just burst out, so she just nods and keeps her head bent down but this doesn’t seem to bother Sister Beatrice, who just says, ‘I understand that you two are good friends, are you not?’ I nod on behalf of us both, and she goes on, ‘I hear very positive things about the two of you, especially about your needlework skills, and I have some very exciting news.’

She goes on to tell us that the grand lady who came a few months ago is a duchess and the patron of the Needlework Society and was visiting to inspect the work that the convent was doing for the poor children of the city. She was so impressed by the work Nora and me showed her that she is sending her housekeeper to interview us about going into service.

A duchess! Well, you can imagine how excited we are, but scared too as we haven’t a clue what to expect and our imaginations go into overtime. We was going to live in a beautiful mansion with a huge garden and sew clothes for very important people, and Nora is going to fall in love with one of the chauffeurs but I have my sights set a bit higher, a soldier in the Light Brigade in his red uniform perhaps, or a city gent in a bowler hat. Either way, both of us are going to have our own comfortable houses next door to each other with little gardens where we can grow flowers and good things to eat, and have lots of children who will play together, and we will live happily ever after.

There’s a pause. She clears her throat loudly.

Forgive me, Miss, don’t mind if I has a smoke?

‘Go ahead, that’s fine. Let’s have a short break.’

No, I’ll just light up and carry on, please, ’cos if I interrupt meself I’ll lose the thread.

A cigarette packet being opened, the click of a lighter, a long inward breath and a sigh of exhaled smoke. Then she clears her throat and starts again.

Not that there’s much chance of me forgetting that day, mind, when the duchess’s housekeeper is coming to visit. We was allowed a special bath and then got dressed in our very best printed cottons and Sister Mary helped us pin our hair up into the sort of bun that domestic servants wear, and a little white lacy cap on top of that.

At eleven o’clock we got summoned into Sister Beatrice’s room again and she looked us up and down and gave us a lecture about how we must behave to the visitor, no staring but making sure we look up when she speaks to us, no talking unless we are spoken to, answering clearly and not too long. She gives Nora a ’specially fierce look and says the word slowly in separate chunks so she’s sure we understand: and there is to be ab-so-lute-ly no giggling.

‘How you behave this morning will determine your futures, young ladies,’ she said. ‘Do not throw this opportunity away.’

She went on some more about if we got chosen we must do our work perfectly and never complain or answer back or we’ll be out on the streets because we can’t never return to The Castle once we have gone. My fantasies melted on the spot. We was both so nervous even Nora’s laugh had vanished.

The housekeeper was a mountain of a woman almost as wide as she was tall, and fierce with eyes like ebony buttons, and spoke to us like she’s ordering a regiment into battle.

She wanted to see more examples of our needlework because, she said, we would be sewing for the highest in the land.

‘“The highest in the land”?’ Nora whispered as we scuttled off down the corridors to the needlework room to get our work. ‘What the heck does that mean?’

‘No idea,’ I said. My brain was addled with fear and I couldn’t think straight for all me wild thoughts.

We were told to lay our work out on Sister Beatrice’s table, and the mountain boomed questions at us: what is the fabric called, what needles did we use and what thread, why did we use those stitches, what did we think of the final result? We answered as well as we could, being clear but not too smart, just as Sister told us. One of my pieces was the start of a patchwork. I’d only finished a couple of dozen hexagons as yet but I was pleased with the way it was shaping up, and when I showed her the design drawn in coloured crayons on squared paper she said, ‘The child has some artistic talent, too.’

‘Indeed,’ Sister Beatrice said back, ‘Miss Romano is one of our best seamstresses,’ and my face went hot and red with pride.

When the housekeeper sat down the poor old chair fair creaked in torment and Nora’s giggles returned, shaking her shoulders as Sister Beatrice poured the tea. Not for us, mind. We just stood and waited, my heart beating like I’d just run up all four staircases at The Castle, while they sipped their tea, oh so ladylike. She ate four biscuits in the time it took to give us a lecture about how we must, as she called it, comport ourselves if we was to be invited to join the duchess’s household: no answering back, no being late for anything ever, no asking for seconds at dinner, no smoking, no boyfriends, wearing our uniform neat and proper every day, clean hands, clean face, clean hair, always up, no straggly bits.

When she stopped there was a pause, and I was just about to say we are good girls, Miss, very obedient girls, but she put her cup and saucer down on the table with a clonk and turned to Sister Beatrice and said, ‘I think these two will do very nicely. Our driver will come to collect them the day after tomorrow.’

Oh my, that drive was so exciting. Don’t forget we’d been stuck in The Castle for most of our lives, never been in a coach, never even been out of the East End. Our eyes was on stalks all the way, like we had never seen the wonderful things passing by, watching the people doing their shopping, hanging out their washing, children playing. In one place we passed a factory at clocking-off time and got stuck in a swarm of men on bicycles – like giant insects, they looked to us – and so many we quickly lost count. They saw us gawping through the coach windows and waved, which made them wobble all over the place, and it was an odd feeling to be noticed, not being invisible for once.

It was just as well we had plenty to distract us ’cos by the time we’d said our goodbyes at The Castle both of us were blubbing. Strange, isn’t it, you can spend so many years wishing yourself out of somewhere and, once you get out, all you want to do is go back? Not that I ever felt that about this place. It’s a funny old feeling, coming here today, I can tell you.

‘It was very good of you to take the trouble to see me.’

Don’t mention it, dearie. Makes a good day out, Nora said. Now, where was I?

‘You were sad to leave The Castle.’

Ah yes, them nuns was a kindly lot, as I think I’ve said before – forgive my leaky old brain, dearie – but they never showed it, not till the last minute when both Sister Mary and Sister Beatrice gave each of us a hug and pressed little parcels into our hands. I nearly suffocated in all those black folds, but this was what set me off on the weeping – it showed they really did care about us, after all. We waved at all the other children peering through the windows and climbed up into the coach with the lay sister Emily, who was to be what Sister Beatrice called a chaperone.

After a while the dirty old streets of the East End turned into clean, wide roads with pavements for people to walk, and tall beautiful houses either side.

‘I didn’t know we was going to the countryside,’ Nora whispered to me, pointing out her side of the coach and sure enough it was green grass, shrubs and trees stretching away as far as our eyes could see, and even people riding horses. Around the edges were real flowers, planted in dazzling carpets of colour, brighter than you could imagine. More brilliant even than the printed cottons we loved so much.

‘That’s Hyde Park, silly,’ sharp ears Emily said, ‘where the grand ladies and gentlemen go to take the air, to walk or ride.’ Well, that silenced us both – the very idea of having the time to wander freely in a beautiful green place like that – and it wasn’t long after that the coach passed beside a long, high wall and slowed down to enter a gate with guardsmen on either side, went round the back of a house so tall I had to bend down beside the window to catch a glimpse of the roof, and then we came to a stop.

We had arrived.

The voice stops and the tape winds squeakily for a moment or two then reaches the end, and the machine makes a loud clunk as it switches itself off.

Chapter Two

London, January 2008

‘Panic stations, darling. The Cosy Homes people are coming next week, and they say I have to clear the lofts before they get here, and Peter down the road was going to help me, you know, the man who suggested it all in the first place, but he’s gone and hurt his back so he can’t come any more and I don’t know what I’m going to do …’

My mother Eleanor is seventy-three and her memory’s starting to fail, so it doesn’t take much to upset her. Plus she’s always nervous on the telephone.

‘Slow down, Mum,’ I whispered, wishing she wouldn’t call me at work. The office was unusually quiet – it was that depressing post-Christmas period when everyone is gloomily slumped at their desks pretending to be busy while surreptitiously job hunting. ‘You’re going to have to tell me what all this is about. For a start, who are Cosy Homes?’

‘The insulation people. It’s completely free for the over-seventies, imagine that, and they say it will cut my heating bills by a quarter and you know what a worry the price of oil is these days so I could hardly refuse, could I? I’m sure I told you about this.’

I racked my brains. Perhaps she had, but with everything that had been going on in the past few days, I’d clearly forgotten. On our first day back after the break we’d received an email announcing yet another round of redundancies. Happy New Year, one and all! Morale was at an all-time low and the rumour mill working overtime. And, joy of joys, next week we were all to be interviewed by some of those smug, overpaid management consultants the company had called in.

I didn’t really want to be here anyway – it was only meant to be an ‘interim job’ to raise enough cash to realise my dream of starting my own interior design business. But the macho, target-driven environment, the daily bust-a-gut expectations and ridiculous deadlines had become surprisingly tolerable when I saw the noughts on my monthly pay slip and annual bonus-time letter. The financial rewards were just too sweet to relinquish. Especially now that I was newly single, with a massive mortgage to cover.

‘It’s okay, Mum,’ I said, distractedly scrolling down the recruitment agency website on my screen. ‘I was planning to come at the weekend, anyway. I’m sure we can get it sorted together in a few hours.’

I heard her relieved sigh. ‘Oh could you, dearest girl? It would be such a weight off my mind.’

My Mini can virtually drive itself to Rowan Cottage, home for the first eighteen years of my life. My parents moved there in the 1960s, after they married and my father was recruited by the new university that had recently opened on the outskirts of Eastchester. He was already in his fifties and there was a twenty-year age difference between them – they met at University College, London, where he had been her doctorate tutor – but it was a very loving marriage. I was born five years later, to the great joy of both.

When I was three years old, he and my grandfather were killed in a terrible head-on collision on the A12 in heavy fog. All I can recall of that dreadful night is two large policemen at the door, and the woman officer who held me when my mother collapsed. She took my hand and walked me down the lane in my pyjamas and slippers, clutching my favourite teddy, to be looked after by our neighbours.

My grandfather was fairly senior in the local police, and my father by then a noted academic, so the accident was widely reported, but no cause ever explained. When I turned seventeen and began to take driving lessons, I asked Mum who’d been at the wheel that night, whether anyone else had been involved or whose fault it had been, but her eyes had clouded over.

‘We’ll never know, dear. It was a long time ago. Best let sleeping dogs lie,’ was all she would say.

Thanks to my father’s life insurance policy she managed to hang on to the house and kept his spirit alive by displaying photographs in every room and talking about him frequently. He looked like a typical sixties academic, with his gold-rimmed glasses and baggy olive green corduroy jacket, leather-patched at the elbows, often with his head in a book or a journal. Mum always says that she fell for his eyes, a kingfisher blue so brilliant that they seemed to hold her in a magic beam every time he looked at her.

There he is, frozen in time, lighting his pipe, playing cricket at a family picnic, sitting in the car with our small dog, Scottie, on his knee. In the photographs he seems to wear a perpetual smile, although apparently he could also be impatient and bossy – traits which, alas, he seems to have passed on to me. I have also inherited his slight stature, blond hair, blue eyes and fair skin, although the genes that gave him a brilliant academic brain seem to have passed me by. I’m more like my mother in temperament: always daydreaming and with a tendency to become distracted.

Money must have been tight. We had few luxuries but I always felt happy and loved, and never overly troubled by the lack of a father in my life. Mum never had any other relationships, not that she let me know about, at least. ‘You should join a dating agency,’ I suggested once – such things appearing to my teenage self as exotic and daring.

She brushed away the suggestion. ‘What a stupid idea,’ she said. ‘Why would I want a new beau? I’ve got my house and my health, my friends and my singing. And I’ve got you, my lovely girl. I don’t need to go out dating at my age.’

I took the slip road off the A12 and into the peace of the lanes. After the urban sprawl and unlovely highways of outer London, North Essex is surprisingly rural and beautiful. At this time of year, furrows in the bare fields collect rainwater and reflect silver stripes of sky against the brown soil; giant elms and oaks stand leafless and black against the wide sky, and rooks gather in their branches each evening, their fierce cawing echoing across the countryside.

Every village is dominated by an outsized flint church, each with its tower reaching robustly towards heaven, built in medieval times by a landed gentry grown fat on wool farming, who sought to secure their seats in paradise. These days the villages still attract fat cats: sleek City types drawn here by the newly-electrified line to Liverpool Street, who worship the great god of annual bonuses and whose vision of paradise is a new Aga in the kitchen, a hot tub on the patio and a sports car in the double garage.

At the end of the lane, in a shallow dip between two gentle hills, is a small green clustered around with a dozen cottages and farm buildings now converted into the price-inflated dream homes of weary commuters. At the edge of the green is Rowan Cottage, once a pair of farm labourers’ houses, with a pantiled roof and dormer windows. It’s the scruffiest property around but, unlike most of the others, seems to be fully at ease with the landscape, as if it has always been there.

As a teenager I hated the isolation, and the fact that the last bus left our local town at the ridiculously early hour of nine o’clock. But Mum still loves it here. After her shockingly early widowhood, she gave up her own academic ambitions and took a job as a school secretary so that she could be at home for me. Then, when I was about ten, she took a part-time job as a lecturer at the local polytechnic and, on those days, my grandmother would pick me up from school, take me back to her house and indulge me with chocolate biscuits.

Granny Jean, my father’s mother, was a feisty old woman with strong views, who read The Times from cover to cover, finished the crossword in a few hours and always had a book or a notebook and pen at her side, and sometimes a needle, darning, sewing up a hem or taking in a seam.

I loved going to stay with her, even though she refused to have a television. After tea, she would read to me all the children’s classics: Wind in the Willows, the Just So Stories and, my favourite, Alice in Wonderland. Of course I was too young to get Carroll’s surreal humour, but I loved the illustrations, especially the ones of Alice with long hair held back with that trademark hairband, her white apron, puffed sleeves and blue stockings. Oh how I wanted long hair and a pair of bright blue stockings!

When I grew old enough, Granny taught me how to sew: embroidery stitches and some very basic dressmaking. One memorable weekend, when I was about twelve and desperate for the latest fashions, we made a lurex mini-skirt – I cringe to recall it, but this was the 1980s after all – which I adored but never had the courage to wear. I’m sure it was Granny’s influence which led me, in the end, to study fashion.

But after she died and there were just the two of us left, it became ‘Mum and Caroline against the world’, a close, almost hermetic relationship which has left me with an overdeveloped sense of duty and a fear of letting her down. Her job was demanding, dealing with unruly students and warring staff, and I sometimes wonder whether the stress of being a single working parent, on top of the grief of losing her husband and father-in-law on a single day, caused changes in her brain that, many years later, have resulted in the tragic and insidious onset of her dementia.

Mum’s face lit up when, after a second’s hesitation, she recognised me.

‘Caroline, dearest girl, how lovely to see you,’ she said, reaching out with skeletal arms. She used to be tall, with dark curly hair and high colour to her cheekbones, but she’s shrinking now and her hair is now almost pure white, her skin pale grey. She seems, literally, to be fading away.

‘Come in, come in, I’ll get the coffee on,’ she said, leading the way to the kitchen, all stripped pine and eighties brown-and-orange decor. Little has changed at Rowan Cottage since I left home, and my interest in interior design must surely have been triggered by my parents’ lack of it. Their minds were focused on higher matters; what did anyone care what the inside of their house looked like, or how ragged the furnishings, so long as they were still serviceable and comfortable?

As a teenager I was so embarrassed by what I perceived as my parents’ lack of style that I refused to invite friends home. These days I’ve come to accept that Mum feels comfortable here, and will never change it. Colours and patterns clash with joyous abandon, chintz loose covers fight with geometric cushions, Persian carpets lie alongside rugs in swirly sixties designs – quite retro cool these days. Books jumble higgledy-piggledy on cheap pine bookshelves that sag under their weight of words. Some of the furniture, such as the Parker Knoll chairs and G-Plan coffee table, is so old-fashioned that it’s become desirable again.

The bedrooms are built into the roof of the cottage, just two of them, each with a dormer window, so there is hardly any proper ‘attic’ above them. But the space between the walls and the angle of the roof has been converted into long cupboards, triangular in section and too low to stand up in, accessed through sliding doors in each bedroom. Despite their awkward shape these cupboards are spacious and, I knew, contained the junk of a lifetime. Clearing them was going to be a mammoth task.

My initial plan was to help Mum do a kind of ‘life laundry’, sorting out what she wanted to keep and giving the rest away. But the idea was stupidly ambitious and it soon became clear it was going to take far too long. We ended up hauling everything out of the cupboards and piling it up in my old bedroom, now a spare room.

Before long we had constructed a small pyramid: boxes of books and papers, old toys, trunks of clothes too good to give away but too outdated ever to be worn again, loose off-cuts of carpet, broken chairs, ancient empty suitcases, stray rolls of wallpaper and even several pairs of old-fashioned leather ice-skates, kept in case the pond should freeze over as it did in the seventies. We could sort it all out later, I reassured Mum, once Cosy Homes had done their work.

It was back-breaking, stooping inside the low spaces and lifting heavy cases and, after a couple of hours, the pyramid had become a mountain almost filling the room. My hands were black with dust and my hair full of cobwebs.

‘However did you manage to accumulate so much stuff?’

Mum gave me a stern look. ‘It’s not all mine. Some of it belongs to you, all those toys and children’s books you wouldn’t let me give away. If only you’d move into a proper house you’d have room for it.’

I hadn’t told her yet, but the prospect of living in a ‘proper house’ and having any need for toys and children’s books was looking extremely remote. A few weeks ago, just before Christmas, my boyfriend Russell and I had, by mutual consent, decided that our five-year relationship was really going nowhere, and he’d moved out. Of course I was sad, but relieved that we’d finally made the decision, and ready to enjoy my newly single status. At least, that’s what I tried to convince myself although, to be totally honest, what I mostly wanted was to find the right man, whoever that was. At thirty-eight I am only too aware of the biological clock ticking ever more loudly as each year passes.

‘Not just the baby things,’ Mum was saying, ‘there’s Granny’s stuff that I’m keeping for you.’

‘I’ve already got the books, the clock and the dining chairs she wanted me to have. Was there something else?’

‘There’s that quilt.’ She looked around vaguely. ‘It’ll be in one of these bags, somewhere.’

‘The patchwork thing that used to be on her spare bed? She used to tell me stories about it.’

‘I wonder where it’s got to?’ She gazed, bewildered, at the mountain.

‘Let’s not get distracted. Just a couple more things to clear.’ I bent into the cupboard once again, crawling to its furthest, darkest corner. Almost the last item was an old brown leather suitcase. I hauled it out and, as I dusted it off, three letters embossed into the lid became clear.

‘Who’s A.M.M., Mum?’

She frowned a moment. ‘That’ll be your grandfather, Arthur Meredith Meadows. I wonder what …?’ She struggled to release the clasps, but they seemed to be rusted closed.

‘Why not give yourself a break, Mum? I’ll have a go at opening that later. Go downstairs and make yourself a cuppa. I can manage the last few boxes on my own, and then we’re done.’

When all of the loft spaces were cleared, I lugged the old suitcase downstairs into the living room and, with the help of a screwdriver and a little force, the locks quickly came free. Inside, on top of a pile of fabrics, was a faded yellow striped sheet.

‘It’s only old bed linen,’ I called through to the kitchen. ‘Shall I take it to a charity shop?’

Mum set down the tea tray. ‘That’s it,’ she said, her face lighting up, ‘the quilt we were talking about.’

She was right: the sheet was just a lining. As I lifted the quilt out and unfolded it right side out across the dining table, light from the window illuminated its beautiful, shimmering patterns and dazzling colours. True, it was faded in places but some of the patches still glittered, almost like jewels. Textiles, plain and patterned, shiny satins, dense velvets and simple matt cottons, were arranged in subtle conjunctions so that groups of triangles took on the shape of a fan, semicircles looked like waves on the sea, squares of light and dark became three-dimensional stairways climbing to infinity.

The central panel was an elegantly embroidered lover’s knot surrounded by a panel of elongated hexagons, and a frame of appliqué figures so finely executed that the stitches were almost invisible. And yet, for all the delicate needlework, the design of the quilt seemed to be quite random, the fabrics so various and contrasted it could have been made by several people, over a long period of time.

‘Did Granny make this?’

‘I don’t think so,’ Mum said, pouring the tea. ‘She liked to sew but I never saw her doing patchwork or embroidery.’

‘Why’s it been hidden away for so long?’

‘Not really sure. You wouldn’t have it on your bed – said it was too old-fashioned or something.’

‘Can I take it home with me now?’

‘Of course, dear. She always wanted you to have it.’

It was only when I went to fold the quilt back into the suitcase that something on its reverse side caught my eye. In one corner of the striped sheet backing, cross-stitched inside an embroidered frame like a sampler, were two lines set out like a verse. Some of the stitching was frayed and becoming unravelled, but I could just about make out the words:

I stitched my love into this quilt, sewn it neatly, proud and true.

Though you have gone, I must live on, and this will hold me close to you.

I read it out to Mum. ‘It’s a poem. Did Granny dedicate it to Grandpa? Or was it for Dad?’

‘Just a mo … I’m just trying to remember something.’ Mum rubbed her temple. ‘I don’t think it was Jean who sewed it. It was something she said once …’

I waited a moment, trying to be patient with my mother’s failing memory.

‘Something about the hospital …’

‘Eastchester General?’

‘No, the other place, you know? It might have been someone she met there. Oh, it’s all so long ago now,’ she sighed, wearily. ‘When your father was a boy. Had a bit of a breakdown, poor old thing.’

‘Granny had a breakdown? I never knew about that. She had to go into hospital?’

‘Not for long. Just till she’d got better. It wasn’t far from here …’

‘And you said she met someone there who might be connected with the quilt?’ I prompted, but it was no good. I could see she was exhausted now. I started my usual routine before leaving her: cleaning up the kitchen, sorting out the fridge, taking out the rubbish and making a sandwich for her supper.

When I returned to the living room she was fast asleep. I wrapped a rug around her and kissed her tenderly on the forehead. It tore at my heartstrings to see how vulnerable and old she looked these days, and I wondered how long it would be before she was unable to manage on her own.

Back at my flat in London, I unfolded the quilt across the spare bed, scanning both sides to make sure I hadn’t missed any clues, and re-read the cross-stitched lines of that sentimental little verse several times, as if by studying them long enough they might yield their secret. One thing was clear: it certainly wasn’t the sort of thing my feisty grandmother would ever have composed.

Chapter Three

Cassette 1, side 2

That was a nice cuppa, thank you dearie. Much needed. So where was I?

‘You and Nora were going into service. You had just arrived at the big house.’

Oh my lord yes. What a day! We was terrified, of course. Nora, me and Emily got bundled out and straight down some steps into the basement; the servants’ entrance, you see, away from the eyes of upstairs. We stood in a dark, echoey hallway for what seemed like an hour while they called someone to call someone else, and finally a maid came and said she was to take us to our room.

We said goodbye to Emily and dragged our bags up hundreds of stairs to our room, which had four beds in, and the two closest the fire was already taken so Nora and me put our things on the other two cots and waited for someone to come and tell us what to do. The room was bare and the beds narrow and hard, but we weren’t much bothered by that ’cos we didn’t know any different. While we waited, we opened the little parcels Sister Beatrice gave us and ate the biscuits she had wrapped inside – oatcakes with a sprinkle of brown sugar – and the taste reminded me so much of The Castle that I started snivelling all over again.

The maid came back and told us we must hurry now, as we must never keep Mrs Hardy waiting. It turned out that Mrs Hardy was the mountain of a housekeeper, the one who came to interview us. Her office under the stairs was not a large room and felt even smaller with her filling up most of the space.

‘Ah, you two, wherever have you been? Come and get your uniforms. Now!’ she bellowed. I started to say we haven’t been anywhere, Ma’am, but Nora dug me in the ribs and put a finger to her lips to remind me that we was not allowed to answer back, or do anything except be clean, neat, hardworking and obedient. Them nuns was so quiet spoken that we was petrified of the woman’s shouting but we soon learned that was how she usually talked to anyone beneath her station.

We grew used to life at the new place pretty quickly, Nora and me, and it wasn’t a bad one. It was nothing near as friendly as at The Castle, mind, but we just had to get on with it and we had hardly any free time to dwell on anything. Our uniforms was plain pale blue with black stockings and we got new black shoes, too, and it was a relief to get out of the clothes what was growing too small for us anyway.

There was hundreds of servants, not to mention the upstairs lot. The two maids who shared our bedroom had to get up early every morning to make fires so we barely had any time to speak with them. They was nice enough, but kept themselves to themselves, at least till we had been there a few weeks.

We spent our days in the needlework room doing mending for the household, and for the rest of the servants too, and there was only the three of us: the chief needlewoman, Nora and me. It was a small white painted room with no furniture save for the three cutting tables and hard chairs, with high wide windows and the floor painted white, too, what we had to sweep and wipe clean every day. There was no fire, on account of the coal dust would soil our work. Instead there was hot water pipes which we put our feet on when we was working, it were that cold sometimes.

The chief needlewoman, Miss Garthwaite, was surely the ugliest woman we’d ever seen. Not as large as Mrs Hardy, mind, but she made up for it with several double chins and warts on her eyelids and on her hands too. Though she tried very hard to hide them, if she ever touched us we’d shiver and have to make an excuse and run to the toilet to wash ourselves, just in case. Her voice was right posh and we wondered where she’d got that way of talking and how she’d ended up in service. We reckoned she must have been born to a good family but they couldn’t find anyone ugly enough to marry her and take her off their hands.

At first she treated us like we was something blown in off the street but after a few days she softened up, especially when she saw we was quite good at needlework. That didn’t stop us having a laugh at her expense: Nora would go on about finding a toad in the pond at the park and bringing it back to cure her. ‘My prince has come,’ she (that is, Nora) would say all hoity toity, ‘when shall we be married?’ And she’d give the toad (which was a rolled-up sock, or a pincushion) a great smacker on its slimy lips, and the toad (that was me in a deep growly voice) would say, ‘I may be able to cure you, Missus, but I ain’t marrying you, warts or no warts.’ We laughed a lot, Nora and me, when we was just the two of us against the rest of the world, or so it seemed.

They gave us three meals a day in the second servants’ hall and cocoa at night. The food was good, better than at The Castle, and in the evenings the people who weren’t cooking or serving used to sit by the fire and read and smoke and gossip, which is how we learned about who we were working for, and where we were living.

Well, you may not believe me, and the psychiatrist fella says I’m making it up, but it turns out that the grand lady of the house wasn’t a duchess after all, but had become a princess because, canny soul that she was, she’d married a prince, Prince George, who was about to be king because his old dad had died. King of England! And more than that, this place we was living in was Buckingham Palace! We nearly fell off our chairs when we first heard it.

She erupts into a chesty laugh, which turns into a cough.

Sorry about me cough. Don’t mind if I stop for a gasper, do you, always helps to calm it?

‘Please go ahead, Maria.’ The sounds of cigarette packet, lighter, an inward breath and a sigh that seems to clear the cough.

Of course I don’t expect you to believe me either, dearie, not many do. It sounds a bit unlikely, don’t it, little old me working at Buckingham Palace? But you can ask Nora – she was there. Well, we didn’t even believe it ourselves at first – thinking we must have understood it wrong but later we found out it was the truth. Fancy, Nora and me working for the future Queen of England! Her name was May, which seemed to us the most beautiful name in the world and after that, on the warm spring days when we was allowed out for walks in St James’s Park, we’d make ourselves daisy-chain crowns and dance under the hawthorn bushes pretending that we were both Queens of the May.

Well, the household was all at sixes and sevens because so many important occasions was about to take place. A coronation in June when May would become Queen Mary, and after that the oldest son, whose name is David, was to be what they call invested as Edward, Prince of Wales. Why those people had to keep changing their names was a mystery to us. What would be wrong with Queen May, or Prince David for that matter?

Of course we never met any of them because our lives was lived downstairs, and we weren’t involved in the planning because all the robes and gowns were made by official costumiers and designers and all the fittings took place in the royal rooms, where me and Nora had never been and never expected to. But there was such an air of excitement and tension everywhere, and because of so much coming and going, so many visitors and suchlike staying at the palace, we got more and more repairs to do: darning socks and stockings, mending torn seams, taking up hems, letting out or taking in darts.

We never knew whose clothes we was working on – Miss Garthwaite kept all that close to her chest – but we could tell they was just servants’ clothes. Not the housemaids or outside servants of course, but the housekeeper, the butler, the valets and the ladies’ maids, we did their mending because they were too busy to do their own and because they had to be dressed perfect every time they went upstairs.

After a while, Miss G came to trust us and started to give us more complicated work on interesting pieces which, we guessed, might belong to the lords and ladies, as some of them fabrics was so soft and beautiful, and the designs like paintings you would want to hang on your wall. Their names were strange to our ears – brocade and black bombazine, chiffon and crêpe de chine, cashmere and organzine – and this made sense when Miss G told us that most silks were called by French words, on account of the weavers who came across the Channel in the olden days.

Every now and again she was summoned upstairs to make a last-minute mend, or adjust a hem or a dart which the ladies’ maids or valets didn’t have time for, and this turned her into a right flap. When she got back she would be flustered and huffy, snapping at anyone who dared to talk. It would take her a good hour or so to recover her nerves.

As Coronation Day came closer there was more and more work for us, and Miss G got called more often, to the point that one day we thought she might just go pop with the stress of it all. She never said what she had been doing or who she had been helping, and we wasn’t allowed to ask her, but my curiosity was so keen I felt like a kettle boiling with its lid clamped on tight. When she went out and left us on our own we had a good laugh, Nora and me, and would sometimes get up and jump about a bit just to let off steam.

On the big day even the underlings like us was allowed to look out of a window on the fourth floor which overlooked the palace gates and The Mall. Well, I’ve never seen so many people in one place, not before nor since. There must have been millions, like when you stir up an ants’ nest by mistake and they all come swarming about, only this lot were so packed in there was no room for them to move, so they were just standing and waving.

There was a long procession of red and gold uniforms on horseback and eventually there was the top of the coach which looked like a crown itself, and though of course we couldn’t see inside ’cos we were looking from so high up, they told us it was Prince George and Princess May, who would come back as King George and Queen Mary. When the crowd saw the coach we could hear a cheer like a roar of thunder which went on for the whole time till everyone had passed, and then we had to go back to work.

In the evening we was told there’d be a ten-course banquet for a hundred guests and the chefs and kitchen staff were frantic so we kept well out of their way, and after our supper we were sent back to work because Miss G kept getting summoned upstairs to help the ladies’ maids and valets with emergency repairs to ballgowns and penguin suits.

The following day the fuss and bother continued, what with all the visiting royalty, and our meals were weird and wonderful left-overs from the banquets: I had never eaten venison before and I was enjoying it till they told me it was deer, them pretty little animals we used to spy in the parks in the early mornings, and then I lost my appetite for it.

That day we overheard conversations in the staff quarters about the prince’s birthday celebrations, and how because he was next in line to the throne he would become king when his father died. There was a deal of discussion about who he would marry – German royalty or Russian? I remember feeling sorry for him, thinking how strange it must be to have your life all mapped out for you. Of course I never understood that I had precious little control over what happened to me, neither. Like all young girls I believed I would fall in love and marry who I liked, and if they had enough money we could have our own little place and not live in servants’ quarters for the rest of my life. If only I’d known what life had in store – what a joke fate would play on me.

A couple of days later after the Coronation, Mrs Hardy calls us servants together after breakfast and tells us to make sure we’re dressed extra-smart, polished shoes and the rest because we had been summoned. We hadn’t a clue what this meant, but there was such an air of excitement it felt a bit like a holiday. We were gathered in the main hall at eleven o’clock sharp and it took a while for all two hundred of us to traipse up the stairs. At the top we went through a door into another world, a world of thick carpets and high ceilings, tall windows and larger-than-life paintings of grand people from history. Imagine two hundred people all walking in silence, and no footsteps to be heard because the carpets are that deep they swallow all the sound. I got ticked off for gawping with my mouth open at the mountains of glittering glass hung in the ceiling what I later found out were called chandeliers, not to mention the dazzling redness of the wallpaper and the glowing gold of flowery carvings where the ceilings met the walls. It was like what I imagined heaven to look like, not just someone’s home – hard to get your head around for an orphan girl like me.

Then we arrived in a room the size of a football pitch and got ourselves arranged in rows. I was at the front because I was so short, and Nora was right behind me. After a bit, in came Miss Hardy the head housekeeper, followed by the new king and queen and their children herded by a nanny. I couldn’t stop goggling at the lot of them, but it was the eldest boy who really caught my eye. He would have been about sixteen then, not tall but fair like a Greek god, and with a mischievous look on him.

They stopped in front of us and we all bowed or curtseyed like we was taught, only I put the wrong foot behind and realised too late and stumbled a bit as I tried to change it, and Nora caught me from behind to stop me falling over. When I dared to look up again my cheeks were burning but the golden-haired boy was smiling at me with a face like an angel giving me a blessing, and I couldn’t help but smile back till I caught the nanny glaring at me, and had to study my shoes again.

The king made a speech with that prune-in-his-mouth voice thanking us lot for the hard work that we had all put in to make their Coronation Day run smooth as clockwork, and the queen (our very own May) said something of the same, and then they went to leave, except that just as she turned, May looked directly at Nora and me and said quietly, ‘You two are my little needlework orphans, are you not?’ We both blushed fit to match the carpet but Nora was the first one to find her voice. ‘That’s right, Your Majesty,’ she said, nipping in an extra little bob curtsey.

May said, ‘I hope you are settling in well?’ and this time I managed to reply, ‘We are very happy, thank you, Ma’am.’ She smiled and said, ‘Very good, very good,’ and walked out with the rest of them.

Well you can imagine that Nora and me was on cloud nine for days afterwards; she because the queen had talked to us, and me because I was head-over-heels in love with the boy. Of course I knew this was stupid, but if others could idol-worship their music-hall heroes I reckoned that surely I was allowed my own?

Over the next few days, by sneaky questions, I managed to find out that this was the same boy whose birthday they celebrated the day after the Coronation Day, the boy who will marry some German or Russian princess and eventually become king. Apparently he attended naval college and now was going to become Prince of Wales, which I thought rather curious. Wales is part of Great Britain, so why should it have its own prince? And why not Scotland or Ireland? It was very confusing.

After the fuss and bother of the Coronation it went quiet for a few weeks, which was just as well because there was a summer heatwave and we sweltered in the sewing room with its high windows barely catching the breeze. Miss G felt it the worst and had to have a cloth nearby to wipe her hands on every couple of minutes to save staining her sewing with sweat. Then one day she didn’t turn up for work, and Nora and me just got on with the mending pile, only it was more fun because we could chatter all we liked and play our favourite game of ‘happy ever after’.

Nora’s changed each time we played it, but usually involved marrying someone she had read about in the newspapers which got left lying around the servants’ hall, a music-hall star, or perhaps an explorer, like Shackleton or Scott, having six children and living in a large, comfortable house in the country with servants who never gave her any lip like we did.

My happy-ever-after dreams also came from the newspapers: I wanted to be a suffragette like Emmeline Pankhurst, and I would win the respect of women all over the country by persuading the prime minister to allow votes for women and after that, having become famous, I would marry Prince Edward and become queen. Or, perhaps it would be better to become queen first, and then I could change the rules however I liked.

Miss Garthwaite didn’t return the next day nor the next, and we were told she had been taken poorly with her nerves, and might not be back for a few days. The days stretched into a week and then two, and we were working all hours to keep up, but we didn’t complain because we had no one to interfere or bother with us, a kind of freedom we hadn’t never enjoyed before.

That night I had just climbed into bed, weary as a sack of potatoes, when there was a knock on our door and there was Mrs Hardy, the chief housekeeper, with a gentleman in valet’s uniform beside her, whose face I vaguely remembered from the servants’ hall.

‘Miss Romano, Mr Finch needs your help,’ she said. ‘Get dressed at once, smart as you can. We’ll wait here for you.’

If she hadn’t such a serious face on I’d have thought it was a joke but since it wasn’t I nearly fainted out of sheer terror. I shut the door and started trying to get dressed, and Nora didn’t help by teasing me about going for a midnight rendezvous with my lover.

When I was ready Mrs H said, ‘You’re to get your sewing kit, then go with Mr Finch, and do exactly as he tells you. Remember to curtsey when you are introduced. You must not speak unless you are spoken to, nor look him directly in the eye, and you must do whatever you are told without saying anything at all, except if you have to ask Mr Finch something.’ I nodded to show I’d understood, but I hadn’t a clue who we was going to see – surely not the king himself? – and my heart was pounding so hard I was sure I’d not remember a thing.

Mr Finch strode off with me trotting to keep up, down the stairs of the servants’ wing to the sewing room to collect what Miss G calls her ‘basket of necessaries’, then we was off again, up the stairs to the door which leads into the palace proper, and along those deep carpeted corridors and up more stairs, great wide ones with shiny brass handrails and massive paintings all over the walls, and then along another corridor with so many doors I lost count of them. No one else seemed to be around, no footmen or other servants, nor any other members of the family.

All the while Mr Finch was talking to me. ‘Urgent alterations are required, Miss Romano, to an item of clothing for his investiture,’ he said, and I tried to recall where I’d heard the word before, to give me a clue about where we was headed. Mr Finch was rabbiting on. ‘The costume has been made for him by the royal costumiers but His Royal Highness is not happy with it. I have made a number of adjustments but I have been unable to please him. Specifically, the breeches are too wide and he would like them taken in. The fabric is so fine that it puckers with every stitch, so I hope that your small hands will be more successful than my own efforts. Are you listening, Miss Romano?’

As it slowly dawned on me who we was heading for, I felt sure I would faint clear away before I got there.

‘Yes sir,’ I puffed, ‘I will do my best to please the prince.’

‘Not “the prince”,’ he snapped in a fearsome whisper. ‘“His Royal Highness” it should be, at all times, and you are not to address him directly, ever.’

‘Understood, Mr Finch,’ I said, praying I would remember all the instructions flying my way.

‘We are going to his private chambers, and afterwards you are not to breathe a word to anyone about where we have been, is that understood?’

‘Yes sir,’ I managed to gasp again, just as we arrived. Mr Finch smoothed down his hair and pulled his jacket straight, and I checked that my dress and apron were in order, and my hair still neatly tied back. Then he opened the door.

The tape comes to an end.

Patsy Morton research diary, 2nd June 1970

Meeting with Dr Watts at lunchtime today, as Prof insists, to get the benefit of his ‘guidance’ about my potential ex-patient interviewees. In other words, he wants to make sure I’m only talking to people who will tell it as he wants it told.

To be honest I didn’t take to the man at all. He talked down to me as if I was a child, calling me ‘dear’. I’m not his ‘dear’. We’ve only just met. Perhaps that’s how he treats all women, but by the end I felt like slapping him.

He didn’t seem to have any objections to the other three patients on the list but when it came to Maria Romano he’s definitely warning me off. He started with the usual caution about patient confidentiality and then proceeded to break all his own rules, telling me that she’d been a patient for many years suffering from what he called persistent paranoid delusional mania, and even reading direct from her file, like he really had a point to prove. Of course I didn’t tell him I’ve already started interviewing her!

His secretary came and whispered something in his ear and he asked me to excuse him for a few minutes. He was gone for much longer so I started wandering around his office, looking through the windows, etc., till I noticed he’d left M’s file open on the desk.

I had a quick flick through but it was all a bit technical and there was not enough time to make proper notes. Then remembered I’d brought my camera so took photos of a couple of pages then got jumpy. Dr W came back after about quarter of an hour, all bright and breezy, we chatted a bit more and I said goodbye.

New problem: how to get my photographs of the medical notes developed without revealing personal information? Can’t take them to Boots the Chemist, can I?

Chapter Four

London, 2008

That very week, despite my impeccable answers to those consultants’ crass questions, I was made redundant. ‘Pack-up-your-desk-within-the-hour’ redundant. And although I knew that the immediate dismissal was nothing to do with their assessment of my honesty and everything to do with protecting commercial secrets, it felt as though I’d been kicked in the teeth and all my hard work for them over the past few years was entirely wasted.

‘I just don’t know who I am any more,’ I moaned, pouring myself a third glass of Pinot, when Jo arrived that evening. ‘It sounds so stupid. It was a hellish, boring job and I couldn’t wait to get out. But being made redundant makes you feel as though they haven’t valued a single thing that you’ve done for them, in four years. I walked out of there feeling like a non-person.’

Jo and I have been best friends since fashion college. We’d shared several grubby bedsits in the early years and were virtually inseparable until relationships and careers took us on different paths. I still have a photograph of us on graduation day, snapped by my proud mum. Jo is squinting at the camera in an attempt to please, and I am gazing into the distance, perhaps daydreaming or simply bored by the whole event. Neither of us would wear a traditional gown and mortar board for the occasion, of course, being far too cool for that sort of thing. We opted instead for some of our more outlandish fashion statement outfits, all torn edges and spray painted patterns – we’d dubbed it graffiti chic, as I recall. I cringe whenever I look at it. She is tall and angular, with an unkempt mop of hair blowing into her eyes; I’m a head shorter, slightly built, my round face topped with a rebellious retro-punk hairstyle like a blonde pincushion. It was not a flattering look and soon got discarded once I started job hunting and saw the disdainful glances of the slick-suited bosses I was trying to impress.

She was always fascinated by historical fabrics and went to work as a textile conservator while I spent my first year out of college living on sofas and struggling as an unpaid intern for various interior design companies until landing a dogsbody job. But I hated the cliquey, hothouse atmosphere of the studios and the arrogance of their rich, self-obsessed customers. Before long I was deeply disillusioned, and decided to get out.

When I joined the bank I’d had to adopt the uniform of the City – dark suit and heels, bleached hair in a neat elfin cut and a mask of make-up re-applied several times daily. Jo still disdained such conformity. She went to work in skinny jeans and a tee-shirt, artfully embroidered, dyed or painted, perhaps, but still a tee-shirt. I never envied her temporary contract hand-to-mouth existence, but respected her for hanging on with fierce determination, despite everything, to her long-held passion for textiles. The respect was not reciprocated: Jo had never disguised her disapproval of my ‘selling out’ to the banking world and her disgust at the bonus culture which, for me, was its only real attraction.

Despite our divergent lives we’d remained the best of friends. Although I’d been devastated when Jo and her boyfriend Mark moved to distant south London for more affordable house prices, we met as often as we could, and she was still the only person in the world in whom I could confide really personal things, the person I turned to when everything was going wrong. This evening, she’d decided to stay over because Mark was away on business.

She sat on the floor hugging her knees, dark curls falling in front of her face, reminding me of our student days, before we could afford chairs. ‘Looking on the bright side, perhaps it’ll be the spur you need to get you back into interior design,’ she said. ‘You can do whatever you want. Something you really enjoy.’

She was right, of course. It had always been my plan to save enough to set up my own business but, even with the generous payoff, how could I do this with no job to fall back on, plus a massive mortgage? Once upon a time I’d had talents and passions, but they’d been so neglected recently that they’d probably packed their bags and emigrated.

‘And that, on top of splitting up with Russell …’ I croaked.

Russell and I had parted more in sorrow than in anger. He is a man of such absurdly perfect features that when he enters a room every female glance is drawn involuntarily towards him. As if that didn’t make him desirable enough, he also has a starry career, having just been made the youngest-ever partner in his law firm. We were the perfect match, or so our friends believed, but appearances can be so misleading. Couples may seem enviably united and loving on the outside, but who can tell what goes on behind closed doors?

Apart from our sex life, which was great, Russ and I had little in common. He wasn’t the slightest bit interested in art or interiors, and I’d rather watch paint dry than go to a rugby match, which was his grand passion outside work. He was a massive carnivore and never understood why meat could be so repugnant to me; in his world vegetarians were there to be converted or, at best, baited for their whimsical ways.

His ideal holiday was skiing, hang gliding or white water rafting; I usually wanted to visit galleries and old houses, or simply crash out on a beach in the sun and read. Apart from law tomes and the occasional trashy thriller, I never saw Russell with a book in his hand. For him, relaxation was getting hammered in the bar on a Friday evening, shouting to fellow lawyers. He didn’t do chilling out, and he wasn’t too fond of my alternative ex-uni friends, either. I think he was terrified I might one day give up being a banker and revert to my artsy roots, take up painting again, dig out my eighties tie dye and big earrings, and start serving organic quinoa with every meal.

Despite our differences we got along fine for a few years but, eventually, the sparkle just wasn’t there anymore and, though we’d tried hard to revive it, deep down we both knew we weren’t right for each other. One tearful evening last November we found ourselves admitting it and, although we were both devastated, agreed to spend some time apart.

I calculated that my salary would just about cover the mortgage payments on the flat, so he’d moved out just before Christmas. Apart from a drunken sentimental night together on New Year’s Eve, we were still officially separated and on New Year’s Day, once I’d guzzled enough painkillers to kill the hangover, I promised myself that this would be my year, a year for rediscovering my sense of adventure, my independent spirit. I might even request extended leave from work and go on that round-the-world trip I’d always been too broke, or too timid, to do in my twenties. When I returned, I would start building a business plan for the design company I’d always dreamed of setting up, but never had the courage.

Jo had already spent several evenings consoling me about the break-up; unfailing reserves of mutual sympathy have always been the currency of our friendship. Now, she crawled across the floor and climbed onto the sofa, wrapping her arms around me.

‘You’re having a really crap time, but in a few weeks you won’t believe you were saying these things. You’ll get another job, start meeting other people. You’re so talented you could do anything you want.’

‘High-class escort, perhaps?’

‘No, idiot, something in design,’ she laughed. ‘Something you really enjoy, for once, and not just for the money. Plus, there are plenty of men out there for the taking. You’re so funny, and gorgeous with it, you won’t be single for long, I know it.’

I gulped another massive swig of wine. Jo seemed to be on water. ‘But I’ve just taken on the mortgage. How will I ever afford it? I can’t bear to lose this place.’

Russ and I found our airy top floor flat, in a quiet, leafy north London street, two years ago, and I knew from the moment we stepped through the door that this was the one. We’d redecorated in cool monotones of cream, taupe and dove grey, restored the beautiful marble fireplaces and plaster ceiling roses, furnished it with minimalist Scandinavian furniture and spent a fortune on wood flooring and soft, deep carpets.

‘I’m so sorry to be such a moan. I really appreciate you coming over.’

‘It was the least I could do. You will survive, you know.’

I took a deep breath. ‘Anyway, what’s new in the star-studded world of textile conservation?’

Her face brightened. ‘I’ve had my contract renewed at Kensington Palace. Another two years of security, at least, and I’ve been given some cool projects. There’s a new exhibition planned and they need all hands on deck, which is good news for me.’ She smiled mysteriously. ‘We’re going to need all the money we can get.’

‘Go on. What haven’t you told me?’

‘Now Mark’s got a permanent job and my contract’s been renewed, we think we can afford it so,’ she paused and lowered her eyes, ‘we’re trying for a baby.’

‘Ohmigod, Jo. That’s sooo exciting,’ I squealed. ‘I thought he hated the idea of a buggy in the hallway? I’m so glad he’s come round.’

Even as I congratulated her I could feel the familiar ache of melancholy in my own belly. Each time a friend announced the ‘big news’, I had to steel myself to enter the baby departments in search of an appropriate gift. It was the tiny Wellington boots that really twisted my heart.

Jo knew all this, of course. ‘I’m sorry. It’s hard for you, just when you’ve finished with Russ.’

‘No worries,’ I said, more breezily than I felt. ‘I’m just thrilled for you. And I’ll be the best babysitter in the world.’

As I went to put away the glasses, she called from the spare room: ‘I haven’t seen this quilt before. Is it yours?’

‘I’ve just brought it back from Mum’s; we found it in the loft at the cottage. It belonged to my granny. Look at this,’ I said, showing her the poem.

‘How bizarre. I’ve seen sampler verses incorporated into quilts, but never sewn into the lining like that. Do you know who made it?’