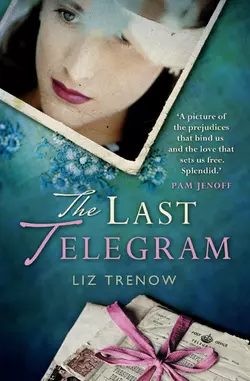

The Last Telegram

Liz Trenow

SPECIAL LOW PRICE FOR A LIMITED PERIOD TO DISCOVER THIS NEW AUTHOR.The war changed everything for Lily Verner.As the Nazis storm Europe, Lily becomes an apprentice at her family’s silk weaving factory. When they start to weave parachute silk there is no margin for error: one tiny fault could result in certain death for Allied soldiers.The war also brings Stefan to Lily: a German Jewish refugee who works on the looms. As their love grows, there are suspicions someone is tampering with the silk.Can their love survive the hardships of war? And will the Verner’s silk stand the ultimate test?The Last Telegram is an evocative and engaging novel for fans of The Postmistress and Pam Jenoff.

LIZ TRENOW

The Last Telegram

Copyright (#ulink_f9da40bb-5b93-5b74-b2be-f6c1e0e775ab)

AVON

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Liz Trenow 2012

Liz Trenow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content or written content has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007480821

Ebook Edition © September 2012 ISBN: 9780007480838

Version: 2018-07-17

In memory of my father, Peter Walters (1919–2011), under whose directorship the mill produced many thousands of yards of wartime parachute silk. All of it perfect.

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u12b0e5b9-562f-5174-8eed-7f620513f06a)

Copyright (#ud872aa7f-5eb6-52e4-84be-39d64124bf87)

Dedication (#ude9c172b-7627-5721-b2e0-bccdce8f3ca2)

Chapter One (#u974e1053-6f2d-52c5-b62a-fdf82d8a3a5f)

Chapter Two (#u9037527c-df02-542e-9ef3-16370742eb9b)

Chapter Three (#u44ab5e50-108c-50aa-8c6b-9e49998c73da)

Chapter Four (#u64ef9a73-c364-52ee-a630-0fd6f1ba1099)

Chapter Five (#uab4d5f18-50cc-56c8-9342-b194d338fc80)

Chapter Six (#u47f54fbf-5a89-55e8-8ac8-02e3418fec2e)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Book Club Q&A for The Last Telegram, by Liz Trenow (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Liz Trenow (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_fb70a6a1-e269-5875-8343-5f4f8a4f3df4)

The history of silk owes much to the fairer sex. The Chinese Empress Hsi Ling is credited with its first discovery, in 2640 BC. It is said that a cocoon fell from the mulberry tree, under which she was sitting, into her cup of tea. As she sought to remove the cocoon its sticky threads started to unravel and cling to her fingers. Upon examining the thread more closely she immediately saw its potential and dedicated her life thereafter to the cultivation of the silkworm and production of silk for weaving and embroidery.

From The History of Silk, by Harold Verner

Perhaps because death leaves so little to say, funeral guests seem to take refuge in platitudes. ‘He had a good innings … Splendid send-off … Very moving service … Such beautiful flowers … You are so wonderfully brave, Lily.’

It’s not bravery: my squared shoulders, head held high, that careful expression of modesty and gratitude. Not bravery, just determination to survive today and, as soon as possible, get on with what remains of my life. The body in the expensive coffin, lined with Verners’ silk and decorated with lilies, and now deep in the ground, is not the man I’ve loved and shared my life with for the past fifty-five years.

It is not the man who helped to put me back together after the shattering events of the war, who held my hand and steadied my heart with his wise counsel, the man who took me as his own and became a loving father and grandfather. The joy of our lives together helped us both to bury the terrors of the past. No, that person disappeared months ago, when the illness took its final hold. His death was a blessed release and I have already done my grieving. Or at least, that’s what I keep telling myself.

After the service the house fills with people wanting to ‘pay their final respects’. But I long for them to go, and eventually they drift away, leaving behind the detritus of a remembered life along with the half-drunk glasses, the discarded morsels of food.

Around me, my son and his family are washing up, vacuuming, emptying the bins. In the harsh kitchen light I notice a shimmer of grey in Simon’s hair (the rest of it is dark, like his father’s) and realise with a jolt that he must be well into middle age. His wife Louise, once so slight, is rather rounder than before. No wonder, after two babies. They deserve to live in this house, I think, to have more room for their growing family. But today is not the right time to talk about moving.

I go to sit in the drawing room as they have bidden me, and watch for the first time the slide show that they have created for the guests at the wake. I am mesmerised as the TV screen flicks through familiar photographs, charting his life from sepia babyhood through monochrome middle years and into a technicolour old age, each image occupying the screen for just a few brief seconds before blurring into the next.

At first I turn away, finding it annoying, even insulting. What a travesty, I think, a long, loving life bottled into a slide show. But as the carousel goes back to the beginning and the photographs start to repeat themselves, my relief that he is gone and will suffer no more is replaced, for the first time since his death, by a dawning realisation of my own loss.

It’s no wonder I loved him so; such a good looking man, active and energetic. A man of unlimited selflessness, of many smiles and little guile. Who loved every part of me, infinitely. What a lucky woman. I find myself smiling back, with tears in my eyes.

My granddaughter brings a pot of tea. At seventeen, Emily is the oldest of her generation of Verners, a clever, sensitive girl growing up faster than I can bear. I see in her so much of myself at that age: not exactly pretty in the conventional way – her nose is slightly too long – but striking, with smooth cheeks and a creamy complexion that flushes at the slightest hint of discomfiture. Her hair, the colour of black coffee, grows thick and straight, and her dark inquisitive eyes shimmer with mischief or chill with disapproval. She has that determined Verner jawline that says, ‘don’t mess with me’. She’s tall and lanky, all arms and legs, rarely out of the patched jeans and charity-shop jumpers which seem to be all the rage with her generation these days. Unsophisticated but self-confident, exhaustingly energetic – and always fun. Had my own daughter lived, I sometimes think, she would have been like Emily.

At this afternoon’s wake the streak of crimson she’s emblazoned into the flick of her fringe was like an exotic bird darting among the dark suits and dresses. Soon she will fly, as they all do, these independent young women. But for the moment she indulges me with her company and conversation, and I cherish every moment.

She hands me a cup of weak tea with no milk, just how I like it, and then plonks herself down on the footstool next to me. We watch the slide show together for a few moments and she says, ‘I miss Grandpa, you know. Such an amazing man. He was so full of ideas and enthusiasm – I loved the way he supported everything we did, even the crazy things.’ She’s right, I think to myself. I was a lucky woman.

‘He always used to ask me about stuff,’ she goes on. ‘He was always interested in what I was doing with myself. Not many grownups do that. A great listener.’

As usual my smart girl goes straight to the heart of it. It’s something I’m probably guilty of, not listening enough. ‘You can talk to me, now that he’s gone.’ I say, a bit too quickly. ‘Tell me what’s new.’

‘You really want to know?’

‘Yes, I really do,’ I say. Her legs, in heart-patterned black tights, seem to stretch for yards beyond her miniskirt and my heart swells with love for her, the way she gives me her undivided attention for these moments of proper talking time.

‘Have I told you I’m going to India?’ she says.

‘My goodness, how wonderful,’ I say. ‘How long for?’

‘Only a month,’ she says airily.

I’m achingly envious of her youth, her energy, her freedom. I wanted to travel too, at her age, but war got in the way. My thoughts start to wander until I remember my commitment to listening. ‘What are you going to do there?’

‘We’re going to an orphanage. In December, with a group from college. To dig the foundations for a cowshed,’ she says triumphantly. I’m puzzled, and distracted by the idea of elegant Emily wielding a shovel in the heat, her slender hands calloused and dirty, hair dulled by dust.

‘Why does an orphanage need a cowshed?’

‘So they can give the children fresh milk. It doesn’t get delivered to the doorstep like yours does, Gran,’ she says, reprovingly. ‘We’re raising money to buy the cows.’

‘How much do you need?’

‘About two thousand. Didn’t I tell you? I’m doing a sponsored parachute jump.’ The thought of my precious Emily hanging from a parachute harness makes me feel giddy, as if capsized by some great gust of wind. ‘Don’t worry, it’s perfectly safe,’ she says. ‘It’s with a professional jump company, all above board. I’ll show you.’

She returns with her handbag – an impractical affair covered in sequins – extracts a brochure and gives it to me. I pretend to read it, but the photographs of cheerful children preparing for their jumps seem to mock me and make me even more fearful. She takes the leaflet back. ‘You should know all about parachutes, Gran. You used to make them, Dad said.’

‘Well,’ I start tentatively, ‘weaving parachute silk was our contribution to the war effort. It kept us going when lots of other mills closed.’ I can picture the weaving shed as if from above, each loom with its wide white spread, shuttles clacking back and forth, the rolls of woven silk growing almost imperceptibly thicker with each turn of the weighted cloth beam.

‘But why did they use silk?’

‘It’s strong and light, packs into a small bag and unwraps quickly because it’s so slippery.’ My voice is steadying now and I can hear that old edge of pride. Silk seems still to be threaded through my veins. Even now I can smell its musty, nutty aroma, see the lustrous intensity of its colours – emerald, aquamarine, gold, crimson, purple – and recite the exotic names like a mantra: brigandine, bombazine, brocatelle, douppion, organzine, pongee, schappe.

She studies the leaflet again, peering through the long fringe that flops into her eyes. ‘It says here the parachutes we’re going to use are of high quality one-point-nine ounce, ripstop nylon. Why didn’t they use nylon in those days? Wouldn’t it have been cheaper?’

‘They hadn’t really invented nylon by then, not good enough for parachutes. You have to get it just right for parachutes,’ I say and then, with a shiver, those pitiless words slip into my head after all these years. Get it wrong and you’ve got dead pilots.

She rubs my arm gently with her fingertips to smooth down the little hairs, looking at me anxiously. ‘Are you cold, Gran?’

‘No, my lovely, it’s just the memories.’ I send up a silent prayer that she will never know the dreary fear of war, when all normal life is suspended, the impossible becomes ordinary, when every decision seems to be a matter of life or death, when goodbyes are often for good.

It tends to take the shine off you.

A little later Emily’s brother appears and loiters in his adolescent way, then comes and sits by me and holds my hand, in silence. I am touched to the core. Then her father comes in, looking weary. His filial duties complete, he hovers solicitously. ‘Is there any more we can do, Mum?’ I shake my head and mumble my gratitude for the nth time today.

‘We’ll probably be off in a few minutes. Sure you’ll be all right?’ he says. ‘We can stay a little longer if you like.’

Finally they are persuaded to go. Though I love their company I long for peace, to stop being the brave widow, release my rictus smile. I make a fresh pot of tea, and there on the kitchen table is the leaflet Emily has left, presumably to prompt my sponsorship. I hide it under the newspaper and pour the tea, but my trembling hands cause a minor storm in the teacup. I decant the tea into a mug and carry it with two hands to my favourite chair.

In the drawing room, I am relieved to find that the slide show has been turned off, the TV screen returned to its innocuous blackness. From the wide bay window looking westwards across the water meadows is an expanse of greenery and sky which always helps me to think more clearly.

The house is a fine, double-bayed Edwardian villa, built of mellow Suffolk bricks that look grey in the rain, but in sunlight take on the colour of golden honey. Not grand, just comfortable and well-proportioned, reflecting how my parents saw themselves, their place in the world. They built it on a piece of spare land next to the silk mill during a particularly prosperous period just after the Great War. ‘It’s silk umbrellas, satin facings and black mourning crepe we have to thank for this place,’ my father, always the merchant, would cheerfully and unselfconsciously inform visitors.

Stained-glass door panels throw kaleidoscope patterns of light into generous hallways, and the drawing room is sufficiently spacious to accommodate Mother’s baby grand as well as three chintz sofas clustered companionably around a handsome marble fireplace.

To the mill side of the house, when I was a child, was a walled kitchen garden, lush with aromatic fruit bushes and deep green salads. On the other side, an ancient orchard provided an autumn abundance of apples and pears, so much treasured during the long years of rationing, and a grass tennis court in which worm casts ensured such an unpredictable bounce of the ball that our games could never be too competitive. The parade of horse chestnut trees along its lower edge still bloom each May with ostentatious candelabra of flowers.

At the back of the house is the conservatory, restored after the doodlebug disaster but now much in need of repair. From the terrace, brick steps lead to a lawn that rolls out towards the water meadows. Through these meadows, yellow with cowslips in spring and buttercups in summer, meanders the river, lined with gnarled willows that appeared to my childhood eyes like processions of crook-backed witches. It is Constable country.

‘Will you look at this view?’ my mother would exclaim, stopping on the landing with a basket of laundry, resting it on the generous windowsill and stretching her back. ‘People pay hundreds of guineas for paintings of this, but we see it from our windows every day. Never forget, little Lily, how lucky you are to live here.’

No, Mother, I have never forgotten.

I close my eyes and take a deep breath.

The room smells of old whisky and wood smoke and reverberates with long-ago conversations. Family secrets lurk in the skirting boards. This is where I grew up. I’ve never lived anywhere else, and after nearly eighty years it will be a wrench to leave. The place is full of memories, of my childhood, of him, of loving and losing.

As I walk ever more falteringly through the hallways, echoes of my life – mundane and strange, joyful and dreadful – are like shadows, always there, following my footsteps. Now that he is gone, I am determined to make a new start. No more guilt and heart-searching. No more ‘what-ifs’. I need to make the most of the few more years that may be granted to me.

Chapter Two (#ulink_ec628ffa-3043-52bf-a578-97c56f59a18a)

China maintained its monopoly of silk production for around 3,000 years. The secret was eventually released, it is said, by a Chinese princess. Given unhappily in marriage to an Indian prince, she was so distressed at the thought of forgoing her silken clothing that she hid some silkworm eggs in her headdress before travelling to India for the wedding ceremony. In this way they were secretly exported to her new country.

FromThe History of Silk,by Harold Verner

It’s a week since the funeral and everyone remarks on how well I’m doing, but in the past couple of days I’ve been unaccountably out of sorts. Passing the hall mirror I catch a glimpse of a gaunt old woman, rather shorter than me, with sunken eyes and straggly grey hair, dressed in baggy beige. That can’t be me, surely? Have I shrunk so much?

Of course I miss him, another human presence in the house; though the truth is that it’s been hard the last few years, what with the care he needed and the worry I lived through. Now I can get on with the task in hand: sorting out this house, and my life.

Emily comes round after school. I’m usually delighted to see her and keep a special tin of her favourite biscuits for such occasions. But today I’d rather not see anyone.

‘What’s up, Gran? You don’t usually refuse tea.’

‘I don’t know. I’m just grumpy, for some reason.’

‘What about?’

‘I haven’t a clue, perhaps just with the world.’

She looks at me too wisely for her years. ‘I know what this is about, Gran.’

‘It’s a crotchety old woman having a bad day.’

‘No, silly. It’s part of the grieving process. It’s quite natural.’

‘What do you mean, the grieving process? You grieve, you get over it,’ I snap. Why do young people today think they know it all?

She’s unfazed by my irritation. ‘The five stages of mourning. Now what were they?’ She twists a stub of hair in her fingers and ponders for a moment. ‘Some psychologist with a double-barrelled name described them. Okay, here we go. Are you paying attention? The five stages of grieving are,’ she ticks them off on her long fingers, ‘denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance – something like that.’

‘They’ve got lists for everything these days: ten steps to success, twenty ways to turn your life around, that kind of rubbish,’ I grumble.

‘She’s really respected, honestly. Wish I could remember her name. We learned it in AS psychology. You should think about it. Perhaps you’ve reached the angry stage?’

She goes to make the tea, leaving me wondering. Why would I be angry? Our generation never even considered how we grieved, though heaven knows we did enough of it. Perhaps there was too much to mourn. We just got on with it. Don’t complain, make the best of a bad lot, keep on smiling. That’s how we won the war, or so they told us.

Emily comes back with the tea tray. Along with knowing everything else she seems to have discovered where I hide the biscuits.

‘No school today?’

‘Revision week,’ she says, airily. ‘What are you up to?’

‘Packing. Sorting out stuff for the charity shop.’

‘Can I help?’

‘There’s nothing I’d like more.’

After tea we go upstairs to the spare room, where I’ve made a tentative start at turning out cupboards and wardrobes that have been untouched for years. Inside one of these mothball-scented mausoleums we find three of my suits hanging like empty carapaces. Why have I kept them for so long? Ridiculous to imagine that one day I might again wear a classic pencil skirt or a fitted jacket. It’s been decades since I wore them but they still carry the imprint of my business self; skirts shiny-seated from office chairs, jacket elbows worn from resting on the table, chin in hand, through many a meeting.

‘Now that’s what you call power dressing,’ Emily says, pulling on a jacket and admiring herself in the long mirror on the inside of the door. ‘Look at those shoulder pads, and such tiny waists. You must have been a looker, Gran. Can I keep this one? Big shoulders are so cool.’

‘Of course, my darling. I thought they went out in the eighties.’

‘Back in again,’ she says, moving the piles of clothes and black bin liners and sitting down on the bed, patting the empty space beside her. ‘You really enjoyed your job, didn’t you?’

‘I suppose so,’ I say, joining her. ‘I never really thought about it before. We were too busy just getting on with it. But I suppose I did enjoy it.’ I hear myself paraphrasing Gwen’s analogy, ‘It’s a kind of alchemy, you know. Like turning dull metal into gold. But better because silk has such beautiful patterns and colours.’

‘That’s rather poetic,’ Emily says. ‘Dad never talks about it like that.’

‘Neither did your grandfather,’ I say. ‘Men are never any good at showing their emotions. Besides, even with something as wonderful as silk, you tend to take it for granted when you work with it every day.’

‘Didn’t you ever get bored?’

I think for a moment. ‘No, I don’t believe I ever did.’

‘You didn’t seem especially happy when I asked you about parachute silk the other day.’

I wish the words would not grip my heart so painfully. ‘It’s only because I don’t like the idea of you jumping out of a plane, dearest girl,’ I say, trying to soothe myself as much as her.

‘I’ll be fine, Gran,’ she says breezily. ‘You mustn’t worry. We’re doing other stuff to raise money, too. If you find anything I could put in for our online auction when you’re turning out your cupboards, that would be amazing.’

‘Anything you like,’ I say. She turns back to the wardrobe and seems to be rummaging on the floor.

‘What’s this, Gran?’ comes her muffled voice.

‘I don’t know what you’ve found,’ I say.

As she pulls out the brown leather briefcase my heart does a flip which feels more like a double cartwheel. It’s battered and worn, but the embossed initials are still clear on the lid. Of course I knew it was there, but for the past sixty years it has been hidden in the darkest recesses of the wardrobe, and of my mind. Even though I haven’t cast eyes on it for decades, those familiar twin aches of sorrow and guilt start to throb in my bones.

‘What’s in it, Gran?’ she asks, impatiently fiddling with the catches. ‘It seems to be jammed.’

It’s locked, I now recall with relief, and the key is safely in my desk. Those old brass catches are sturdy enough to withstand even Emily’s determined tugging. ‘It’s just old papers, probably rubbish,’ I mutter, dazed by this unexpected discovery. I know every detail of what the case contains, of course, a package of memories so intense and so painful that I never want to confront them again. But I cannot bring myself to throw it away.

Perhaps I will retrieve it when she is gone and get rid of it once and for all, I think. Yes, that’s what I’ll do. ‘Pop it back in the wardrobe, darling. I’ll have a look later,’ I say, as calmly as I can muster. ‘Shall we have some lunch?’

After this little shock my enthusiasm for packing goes into a steep decline. I need to pop to the shop for more milk, but it’s just started raining, so I am hunting in the cupboard under the stairs for my summer raincoat when something catches my eye: an old wooden tennis racket, still in its press, with a rusty wing nut at each corner. The catgut strings are baggy, the leather-wrapped handle frayed and greying with mould.

I pull it out of the cupboard, slip off the press and take a few tentative swings. The balance is still good. And then, without warning, I find myself back in that heat-wave day in 1938 – July, it must have been. Vera and I had played a desultory game of tennis – no shoes, just bare feet on the grass court. The only balls we could find were moth-eaten, and before long we had mis-hit all of them over the chain link fence into the long grass of the orchard. Tiptoeing carefully for fear of treading on the bees that were busily foraging in the flowering clover, we found two. The third was nowhere to be seen.

‘Give up,’ Vera sighed, flopping face down on the court, careless of grass stains, her tanned arms and legs splayed like a swimmer, her red-painted fingernails shouting freedom from school. I laid down beside her and breathed out slowly, allowing my thoughts to wander. The sun on my cheek became the touch of a warm hand, the gentle breeze in my hair his breath as he whispered that he loved me.

‘Penny for them?’ Vera said, after a bit.

‘The usual. You know. Now shut up and let me get back to him.’

Vera had been my closest friend ever since I forgave her for pulling my pigtails at nursery school. In other words, for most of my life. By our teens we were an odd couple; I’d grown a good six inches taller than her, but despite doing all kinds of exercises my breasts refused to grow, while Vera was shaping up nicely, blooming into the hourglass figure of a Hollywood starlet.

I was no beauty, neither was I exactly plain, but I longed to look more feminine and made several embarrassing attempts to fix a permanent wave into my thick brown hair. Even today the smell of perm lotion leaves a bitter taste in my mouth, reminding me of the frizzy messes that were the catastrophic result of my bathroom experiments. So I’d opted instead for a new chin-length bob that made me feel tremendously bold and modern, while Vera bleached her hair a daring platinum blonde and shaped it into a Hollywood wave. Together we spent hours in front of the mirror practising our make-up, and Vera developed clever ways to emphasise her dimples and Clara Bow lips. She generously declared that she’d positively die for my cheekbones and long eyelashes.

In all other ways we were very alike – laughed at the same things, hankered after the same boys, loved the same music, felt strongly about the same injustices. We were both eighteen, just out of school and aching to fall in love.

‘Do I hear you sighing in the arms of your lover?’

‘Mais oui, un très sexy Frenchman.’

‘You daft thing. Been reading too much True Romance.’

More silence, punctuated by the low comforting chug of a tractor on the road and cows on the water meadows calling for their calves. School seemed like another country. A mild anxiety about imminent exam results was the only blip in a future that otherwise stretched enticingly ahead. Then Vera said, ‘What do you think’s really going to happen?’

‘What do you mean? I’m going to Geneva to learn French with the most handsome man on earth, and you’re going to empty bed pans at Barts. That’s what we planned, isn’t it?’

She ignored the dig. ‘I mean with the Germans. Hitler invading Austria and all that.’

‘They’re sorting it out, aren’t they?’ I said, watching wisps of cloud almost imperceptibly changing their shapes in the deepest of blue skies. That very morning at the breakfast table my father had sighed over TheTimes and muttered, ‘Chamberlain had better get his skates on. Last thing we need is another ruddy war.’ But here in the sunshine, I refused to imagine anything other than my perfect life.

‘I flipping well hope so,’ Vera said.

The branch-line train to Braintree whistled in the distance and the bruised smell of mown grass hung heavily in the air. It seemed impossible that armies of one country were marching into another, taking it over by force. And not so far away: Austria was just the other side of France. People we knew went on walking holidays there. My brother went skiing there, just last winter, and sent us a postcard of improbably-pointed mountains covered in snow.

The sun started to cool, slipping behind the poplars and casting long stripes of shade across the meadow. We got up and started looking again for the lost ball.

‘We’d better get home,’ I said, suddenly remembering. ‘Mother said John might be on the boat train this afternoon.’

‘Why didn’t you say? He’s been away months.’

‘Nearly a year. I’ve missed him.’

‘I thought you hated him,’ she giggled, walking backwards in front of me, ‘I certainly did. I’ve still got the scar from when he pushed me off the swing accidentally-on-purpose,’ she said, pointing to her forehead.

‘Teasing his little sister and her best friend was all part of the game.’ The truth was that like most siblings John and I had spent our childhood tussling for parental attention, but to me he was always a golden boy; tall like a tennis ace, with a fashionable flick of dark blond hair at his forehead. Not intellectual, but an all-rounder, good at sports, musical like my mother and annoyingly confident of his attractiveness to girls. And yes, I had missed him while he’d been away studying in Switzerland.

Vera and I were helping to set the tea in the drawing room when the bell rang. I dashed to the front door.

‘Hello Sis,’ John boomed, his voice deeper than I remembered. Then to my surprise, he wrapped his arms round me and gave me a powerful hug. He wouldn’t have done that before, I thought. He stood back, looking me up and down. ‘Golly, you’ve grown. Any moment now you’ll be tall as me.’

‘You’ve got taller, too,’ I said. ‘I’ll never catch up.’

He laughed. ‘You’d better not. Like the haircut.’ Reeling from the unexpected compliment, surely the first I’d ever received from my brother, I saw his face go blank for a second and realised Vera was on the step behind me.

‘Vera?’ he said tentatively. She nodded, running fingers through her curls in a gesture I mistook for shyness. He recovered quickly. ‘My goodness, you’ve grown up too,’ he said, shaking her hand. She smiled demurely, looking up at him through her eyelashes. I’d seen that look before, but never directed at my brother. It felt uncomfortable.

‘How did the exams go, you two?’

I winced at the unwanted memory. ‘Don’t ask. Truth will out in a couple of weeks’ time.’

Mother appeared behind us and threw her arms round him with a joyful yelp. ‘My dearest boy. Thank heavens you are home safely. Come in, come in.’

He took a deep breath as he came through the door into the hallway. ‘Mmm. Home sweet home. Never thought I’d miss it so much. What’s that wonderful smell?’

‘I’ve baked your favourite lemon cake in your honour. You’re just in time for tea,’ Mother said. ‘You’ll stay too, Vera?’

‘Have you ever known me turn down a slice of your cake, Mrs Verner?’ she said.

Mother served tea and, as we talked, I noticed how John had changed, how he had gained a new air of worldliness. Vera had certainly spotted it too. She smiled at him more than really necessary, and giggled at the feeblest of his jokes.

‘Why are you back so soon?’ Father asked. ‘I hope you completed your course?’

‘Don’t worry, I finished all my exams,’ John said cheerfully. ‘Honestly. I’ve learned such a lot at the Silkschüle, Pa. Can’t wait to get stuck in at the mill.’ Father smiled indulgently, his face turning to a frown as John slurped his tea – his manners had slipped in his year away from home.

Then he said, ‘What about your certificates?’

‘They’ll send them. I didn’t fail or get kicked out, if that’s what you are thinking. I was a star pupil, they said.’

‘I still don’t understand, John.’ Father persisted. ‘The course wasn’t due to finish till the end of the month.’ John shook his head, his mouth full of cake. ‘So why did you leave early?’

‘More tea, anyone?’ Mother asked, to fill the silence. ‘I’ll put the kettle on.’

As she started to get up, John mumbled, almost to himself, ‘To be honest, I wanted to get home.’

‘That’s nothing to be ashamed of, dear,’ she said. ‘We all get homesick sometimes.’

‘That’s not it,’ he said, in a sombre voice. ‘You don’t understand what it was like. Things are happening over there. It’s not comfortable, ‘specially in Austria.’

‘Things?’ I said, with an involuntary shiver. ‘What things?’

‘Spit it out, lad,’ Father said, gruffly. ‘What’s this is all about?’

John put down his cup and plate, and sat back in his chair, glancing out of the window towards the water meadows at that Constable view. Mother stopped, still holding the pot, and we all waited.

‘It’s like this,’ he started, choosing his words with care. ‘We’d been to Austria a few times – you know, we went skiing there. Did you get my postcard?’

Mother nodded. ‘It’s on the mantelpiece,’ she said, ‘pride of place.’

‘It was fine that time. But then, a few weeks ago, we went back to Vienna to visit a loom factory. Fischers. The owner’s son, a chap called Franz, showed us round.’

‘I remember Herr Fischer, Franz’s father. We bought looms from him once. A good man,’ Father said. ‘How are they doing?’

‘It sounded as though business was a bit difficult. As he was showing us round, Franz dropped a few hints, and when we got outside away from the others I asked him directly what was happening. At first he shook his head and refused to say anything, but then he whispered to me that they’d been forced to sell the factory.’

‘Forced?’ I asked. ‘Surely it’s their choice?’

‘They don’t have any choice,’ John said. ‘The Nazis have passed a new law which makes it illegal for Jewish people to own businesses.’

‘That’s outrageous,’ Father spluttered.

‘His parents think that if they keep their heads down it will all go away,’ John said as I struggled to imagine how all of this could possibly be happening in Vienna, where they trained white horses to dance and played Strauss waltzes on New Year’s Eve.

‘Is there any way we can help them, do you think?’ Mother said, sweetly. Her first concern was always to support anyone in trouble.

‘I’m not sure. Franz says it feels unstoppable. It’s pretty frightening. They don’t know where the Nazis might go next,’ John said solemnly. ‘It’s not just in business, you know. I saw yellow stars painted on homes and shops. Windows broken. Even people being jeered at in the street.’ He turned to the window again with a faraway look, as if he could barely imagine what he’d seen. ‘They’re calling it a pogrom,’ he almost whispered. I’d never heard the word before but it sounded menacing, making the air thick and hard to breathe.

Mother broke the silence. ‘This is such gloomy talk,’ she said brightly. ‘I want to celebrate my son’s return, not get depressed about what’s happening in Europe. More cake, anyone?’

Later, Vera and I walked down the road to her home. She lived just a mile away and we usually kept each other company to the halfway point. ‘What do you think?’ I asked, when we were safely out of the house.

‘Hasn’t he changed? Grown up. Quite a looker these days.’

‘Not about John,’ I snapped irritably. ‘I saw you fluttering your eyelashes, you little flirt. Lay off my brother.’

‘Okay, okay. Don’t lose your rag.’

‘I meant, about what he said.’

‘Oh that,’ she said. ‘It sounds grim.’

‘Worse than grim for the Jews,’ I said. ‘I’m not sure what a pogrom is, exactly, but it sounds horrid.’

‘Well there’s not much we can do from here. Let’s hope your father’s right about Chamberlain sorting it out.’

‘But what if he doesn’t?’

She didn’t reply at once, but we both knew what the answer was.

‘Doesn’t bear thinking about,’ she said.

When I got back Father leaned out of his study door.

‘Lily? A moment?’

It was a small room with a window facing out onto the mill yard, lined with books and heavy with the fusty fragrance of pipe tobacco. It was the warmest place in the house and in winter a coal fire burned constantly in the small grate. This was his sanctuary; the heavy panelled door was normally closed and even my mother knocked before entering.

It was one of my guilty pleasures to sneak in and look at his books when he wasn’t there – The Silk Weavers of Spitalfields; Sericulture in Japan; The Huguenots; So Spins the Silkworm; and the history of a tape and label manufacturer innocently entitled A Reputation in Ribbons that always made me giggle. Most intriguing of all, inside a plain box file, were dozens of foolscap sheets filled with neat handwriting and, written on the front page in confident capitals: A HISTORY OF SILK, by HAROLD VERNER. I longed to ask whether he ever planned to publish it, but didn’t dare admit knowing of its existence.

I perched uneasily on the desk. From his leather armchair by the window Father took a deep breath that was nearly, but not quite, a sigh.

‘Mother and I have been having a chat,’ he started, meaning he’d decided something and had told her what he thought. My mind raced. This was ominous. whatever could it be? What had I done wrong recently?

‘I won’t beat around the bush, my darling. You’ve read the reports and now, with what John told us this afternoon …’

‘About the pogrom?’ The word was like a lump in my mouth.

He ran a hand distractedly through his thinning hair, pushing it over the balding patch at the back. ‘Look, I know this will be disappointing, but you heard what he told us.’

I held my breath, dreading what he was about to say.

‘In the circumstances Mother and I think it would be unwise for you to go to Geneva this September.’

A pulse started to thump painfully in my temple. ‘Unwise? What do you mean? I’m not Jewish. Surely this pogrom thing won’t make any difference to me?’ He held my gaze, his expression fixed. He’d made up his mind. ‘It isn’t fair,’ I heard myself whining. ‘You didn’t stop John going.’

‘That was a year ago. Things have changed, my love.’

‘The Nazis aren’t in Switzerland.’

He shook his head. ‘Not yet, perhaps. But Hitler is an ambitious man. We have absolutely no idea where he will go next.’

‘But Chamberlain …?’ I was floundering, clinging to flotsam I knew wouldn’t float.

‘He’s doing his best, poor man.’ Father shook his head sadly. ‘He believes in peace, and so do I. No one wants another war. But it’s not looking too good.’

I couldn’t comprehend what was happening. In the space of two minutes my future life, as far as I could see it, had slipped away and I was powerless to stop it. ‘But I have to go. I’ve been planning it for months.’

‘You don’t need to make any quick decisions. We’ll let Geneva know you won’t be going in September, but other than that you can take your time.’ Father’s voice was still calm and reasonable. I felt anything but.

‘I don’t want to take my time. I want to go now,’ I whined, like a petulant child. ‘Besides, what would I do instead?’

He felt in his pocket for his tobacco pouch and favourite briar pipe. With infuriating precision he packed the pipe, deftly lit a match, held it to the bowl and puffed. After a moment he took it from his mouth and looked up, his face alight with certainty. ‘How about a cookery course? Always comes in handy.’

I stared at him, a hot swell of anger erupting inside my head. ‘You really don’t understand, do you?’ I registered his disapproving frown but the words spilled out anyway. ‘Because I’m a girl you think my only ambition is to be a perfect little wife, cooking my husband wonderful meals and putting his slippers out every evening.’

‘Watch your tone, Lily,’ he warned.

To avoid meeting his eyes I started to pace the Persian rug by the desk. ‘Times have changed, Father. I’m just as intelligent as any man and I’m not going to let my brain go soggy learning to be a wonderful cook or a perfect seamstress. I don’t want to be a wife either, not yet anyway. I want to do something with my life.’

‘And so you shall, Lily. We will find something for you. But not in Geneva, or anywhere else in Europe for that matter,’ he said firmly. ‘And now I think we should finish this discussion. It’s time for bed.’

I nearly slammed the study door behind me, but thought better of it at the last minute and pulled it carefully closed. In my bedroom I cursed Father, Chamberlain and Hitler, in that order. I loved my room, with its pretty damask curtains and matching bedcover, but these treasured things now seemed to mock me, trapping me here in Westbury. After a while I caught sight of myself in the mirror and realised how wretched I looked. Self-pity would get me nowhere, and certainly not into a more interesting life. I needed to get away from home, perhaps to London, to be near Vera. But what could I do? I was qualified for nothing.

I remembered Aunt Phoebe. She was a rather distant figure, a maiden aunt who lived in London with a lady companion, worked in an office somewhere, drove an Austin Seven all over Europe and cared little for what anyone else thought about her unconventional way of life. Perhaps I could train as a secretary, like her? Earn enough to rent a little flat? The idea started to seem quite attractive. It wasn’t as romantic as Geneva, but at least I would get away and meet some interesting people.

Now all I had to do was convince Father that this was a reasonable plan.

At breakfast the next day I crossed my fingers behind my back and announced, ‘I’ve decided to get a job in London. Vera and I are going to share a bedsit.’ I hadn’t asked her yet, but I was sure she would say yes.

‘Lovely, dear.’ Mother was distracted, serving breakfast eggs and bacon from the hotplate.

‘Sounds fun,’ John said, emptying most of the contents of the coffee jug into the giant cup he’d bought in France. ‘Vera’s a good laugh. What are you going to do?’

‘Leave some coffee for me,’ I said. ‘I could do anything, but preferably something in an office. I’ll need to get some experience first. I thought perhaps I could spend a few weeks helping Beryl at Cheapside?’ Beryl managed Verners’ London office. ‘What do you think, Father?’

‘Well now,’ he said, carefully folding his newspaper and placing it beside his knife and fork. ‘Another Verner in the firm? There’s an idea.’ He took the plate from Mother and started to butter his toast, neatly, right to the edges. ‘A very good idea. But you’d have to work your way up like everyone else.’

‘What do you mean, “work my way up”?’ Was he deliberately misinterpreting what I’d said?

‘You’d have to start like John did, as a weaver,’ he said, moving his fried egg onto the toast.

‘That’s not what I meant. I want secretarial experience, in an office. Not weaving,’ I said, sharply. ‘I don’t need to know how to weave the stuff to type letters about it. Does Beryl have to weave?’

He gave me a fierce look and the room went quiet. Mother slipped out, muttering about more toast, and John studied the pattern on the tablecloth. Father put down his knife and fork with a small sigh, resigned to sacrificing his hot breakfast for the greater cause of instructing his wilful daughter.

‘Let me explain, my dearest Lily, the basic principles of working life. Beryl came to us as a highly experienced administrator and you have no skills or experience. You know very well that I do not provide sinecures for my family and I will not give you a job just because you are a Verner. As I said, you need to learn the business from the bottom up to demonstrate that you are not just playing at it.’

He took a deep breath and then continued, ‘But I’ll make you an offer. Prove yourself here at Westbury and if, after six months, you are still determined to go to London and take up office work, I will pay for you to go to secretarial college. If that is what you really want. Otherwise, it’s a cookery course. Take it or leave it.’

Chapter Three (#ulink_541f5191-5785-5b6b-893d-4ada97259ce8)

Weaving is the process of passing a ‘weft’ thread, normally in a shuttle, through ‘warp’ threads wound parallel to each other on a ‘beam’ of the total width of the cloth being woven. The structure of the weave is varied by raising or lowering selected warp threads each time the weft is passed through.

FromThe History of Silk, by Harold Verner

I never intended to become a silk weaver, but Herr Hitler and my Father had left me with little choice.

Of course I was already familiar with the mill, from living next door, carrying messages for Mother, or visiting to ask Father a favour. It held no romance for me – it was just a building full of noisy machinery, dusty paperwork and hard-edged commerce. The idea of spending six months there felt like a life sentence.

Then, as now, the original Old Mill could be seen clearly across the factory yard from the kitchen window of The Chestnuts: two symmetrical storeys of Victorian red brick, a wide low-pitched slate roof, green painted double front doors at the centre, two double sash windows on either side and three above. These days it’s just a small part of the complex my son runs with impressive efficiency.

Behind Old Mill stretches an acre of modern weaving sheds where the Rapier looms clash and clatter, producing cloth at a rate we could never have imagined in my day. Even now, in the heat of summer, when the doors are opened to allow a cooling breeze, I hear the distant looms like the low drone of bees. It reassures me that all is well.

The ebb and flow of work at the mill had always been part of our family life. In those days employees arrived and departed on foot or by bicycle for two shifts every weekday, except for a fortnight’s closure at Christmas and the annual summer break. It’s the same now, except they come by car and motorbike. Families have worked here for generations, ever since my great-great-grandfather moved the business out of London, away from its Spitalfields roots. In East Anglia they found water to power their mills and skilled weavers who had been made redundant by the declining wool trade.

Even today the weavers’ faces seem familiar, though I no longer know them by name. I recognise family traits – heavy brows, cleft chins, tight curls, broad shoulders, unusual height or slightness – that have been handed down from father to son, from mother to daughter. They are loyal types, these weaving families, proud of their skills and the beauty of the fabrics they produce.

Then, as now, vans pulled into the yard several times a week to deliver bales of raw yarn and take away rolls of woven fabric. When not required at the London office, my father walked to work through the kitchen garden gate and across the yard, and came home for the cooked lunch that Mother had spent much of the morning preparing. She rarely stepped foot in the mill. Her place was in the home, she said, and that’s how she liked it.

When I came in to breakfast that first day John looked me up and down and said smugly, ‘You’d better change that skirt, Sis. You’re better off in slacks for bending over looms. And you’ll regret those heels after you’ve been on your feet for nine hours.’

‘While you sit on your backside pushing papers around,’ I grumbled, noticing his smart new suit and striped tie. It was bad enough that I had to start as a lowly apprentice weaver, but John had recently been promoted to the office, which made it worse.

I’d never envied what was in store for him: a lifelong commitment to the responsibility of running a silk mill in a rural town. As the eighth generation of male Verners it was unthinkable that he would do anything other than follow Father into the business, and take over as managing director when he retired. John was following the natural order of things.

‘I bet you’ll get the old battle-axe,’ he said, crunching loudly on his toast.

‘Language, and manners, please, John,’ Mother muttered mildly.

‘Who’s that?’ I asked.

‘Gwen Collins. Assistant weaving floor manager. Does most of the training. Terrifying woman.’

‘Thanks for the encouragement.’

‘Don’t listen to your brother, you’ll get on splendidly,’ Mother said encouragingly. ‘You never know, you might even enjoy it.’

I was unconvinced. Setting off across the yard, the short trip I had seen my father and, more recently, John, take every morning, I felt depressed: this was far from the glamorous life I’d planned. But why were butterflies causing mayhem in my stomach – was I afraid of being ridiculed as the gaffer’s daughter, I wondered, of letting him down? Or scared that I might not be able to learn fast enough, that people might laugh behind my back? Oh, get a grip Lily, I muttered to myself. This is a means to an end, remember? Besides, you haven’t let anything beat you yet and you’re not about to start now.

I took a deep breath and went through the big green double doors into the mill, and climbed the long wooden stairs to Father’s office.

My first impressions of Gwen Collins were certainly not favourable. She wasn’t exactly old – in her late twenties I judged – but otherwise John’s description seemed pretty accurate. An unprepossessing woman, dumpy and shorter than me, in a shapeless brown overall and trousers with men’s turn-ups, she had concealed her hair beneath an unflattering flowery scarf wrapped and knotted like a turban. There was something rather manly about her – a disregard for how others saw her, perhaps. Her expression was serious, even severe. But something softened it, gave her an air of vulnerability. Then I realised what it was: I had never seen anyone with so many freckles. They covered her face, merging into blobs which almost concealed the pale, nearly translucent skin beneath. She’d made no effort to hide them with make-up. Even her eyelids were speckled.

I returned the forceful handshake with what I hoped was a friendly smile. ‘Pleased to meet you, Gwen. Father tells me you’re going to teach me all you know. He says you’re a mine of information.’

‘Mr Harold is very kind, the regard is mutual,’ she replied without returning the smile, and without even a glance at Father. Pale green eyes regarded me with unsettling intensity beneath her almost invisibly blonde eyelashes.

After an awkward pause she said briskly, ‘Right, we’ll make a start in the packing hall, so you can learn about what we produce, then we’ll go round the mill to see how we weave it.’ With no further pleasantries, she turned and led the way, striding down the corridor so purposefully I had to trot to keep up.

The packing hall was – still is today – a large room running the length of the first floor of Old Mill. Sun poured in through six tall windows along the southern wall, and the room was almost oppressively warm with that dry, sweet smell of raw silk that would soon become part of my very being. Along the opposite wall were deep wooden racks stacked from floor to ceiling with bolts of cloth.

In the centre, two workers stood at wide tables edged with shiny bronze yard-rules, expertly measuring, cutting, and rolling or folding bundles of material and wrapping them with sturdy brown paper and string. On the window side four others sat at tilted tables like architects’ drawing boards, covered with cloth stretched between two rolls, one at the top and another at the bottom.

‘These are pickers,’ Gwen said, introducing me as ‘Miss Lily, Mr Harold’s daughter’. As we shook hands they lowered their eyes deferentially, probably cursing the fact that they would have to watch their language with another Verner hanging around.

‘Just call me Lily, please,’ I stuttered. ‘It’s my first day and I’ve got a lot to learn.’ Naïvely, I imagined they might in time consider me one of them.

‘They check the silk and mark each fault with a short red thread tied into the selvedge, that’s the edge of the fabric,’ Gwen said, pointing at the end of the roll. ‘For every fault we supply an extra half yard – it’s our reputation for quality.’ I nodded frequently, trying to appear more enthusiastic than I felt. ‘Now, how much do you know about silk?’

‘Not much, I’m afraid,’ I admitted, embarrassed. Surely a Verner should have silk in the blood?

I caught the first hint of a smile. ‘I’ll take that as a challenge, then.’

Gwen turned to a shelf and lifted a heavy roll onto the table, steadied an end with one hand and, in a single deft movement, grasped the loose end of the material and pulled out a cascade that unravelled like liquid gold.

‘Wow,’ I said, genuinely dazzled. She crumpled a bundle between her hands, lowering her ear to it. ‘Listen.’ I bent my head and she scrunched it again. It sounded like a footstep on dry snow, or cotton wool tearing. ‘That’s called scroop, a good test for real silk when it’s been dyed in the yarn.’ As I crumpled it the vibration ran through my hands, up my arms and into my ears, making me shiver.

She rolled up the gold with practised ease and pulled out a bolt of vivid scarlet, deep purple and green stripes, spread it across the table with that same skilled movement, then expertly folded a diagonal section into a necktie shape and held it beneath her chin. ‘Tie materials are mostly rep stripes and Jacquard designs,’ she said, ‘woven to order for clubs and societies. Men so love their status symbols, don’t they?’ Again, I saw that puzzling crimp at the corner of her eyes.

‘Jacquard?’

‘Type of loom. Clever bit of kit for weaving patterns, brought here by your Huguenot ancestors. You’ll see our looms when we go down to the weaving shed.’

She unravelled a third roll. This one had a navy background with a delicate gold fleur-de-lys pattern. She pulled a small brass object from her pocket, carefully unfolding it into a tiny magnifying glass hinged onto two plates, one of which had a square hole. She placed this on the silk and gestured for me to put my eye to the glass.

The motif was so enlarged that hair-like individual silk threads, almost invisible to the naked eye, looked like strands of wool so thick that I could measure them against the ruler markings along the inner square of the lower plate. ‘I had no idea,’ I murmured, fascinated by the miniature world under the glass. ‘There’s so much more to it than I ever imagined.’ As I looked up, the glint of satisfaction that passed across Gwen’s face reminded me of my Latin teacher when I’d finally managed to get those wretched declensions right.

She moved along the racking and pulled out a fat roll. ‘This one’s spun silk,’ she said, unravelling the cloth and draping it over my hands. It was heavy, the texture of matt satin, the colour of clotted cream, and wonderfully sensuous. It felt deliciously soft and warm, like being stroked with eiderdown, and almost without thinking I lifted it to my cheek. Then I caught that knowing smile again, felt self-conscious and handed it back rather too hastily. Gwen’s manner was unnerving; most of the time she was coolly professional and business-like, but sometimes her responses were disconcertingly intimate, as though she could read my thoughts.

She looked up at the clock. ‘It’s nearly coffee-break. Just time for the pièce de résistance.’

At first I thought the taffeta was aquamarine. But when its shimmering threads caught the light, the colour shifted to an intense royal blue. It was like a mirage, there one moment and gone the next. ‘Beautiful, isn’t it? It’s shot silk. A blue weft shot through a green warp.’ She held up a length, iridescent as a butterfly wing, into a shaft of sunlight. I almost gasped.

As I took a piece of cloth and angled it to watch the colours change, I could feel Gwen’s pale eyes interrogating my response. And in that moment I realised I’d never before properly appreciated silk, its brilliant, lustrous colours, the range of weaves and patterns. Father and John never talked about it this way.

That morning Gwen showed me how to use all my senses; not just seeing the colours and feeling its weave, but holding it up to the light, smelling it, folding to see how it loses or holds a crease, identifying the distinctive rustles and squeaks of each type of material, examining its weave under a magnifier, enjoying its variety. I was already hooked, like a trout on a fly-line, but I didn’t know it yet. Only later did I come to understand how Gwen simply allowed the silk to seduce me.

The canteen, a large sunny room at the top of Old Mill that smelled not unpleasantly of cabbage and cigarette smoke, seemed to be the heart of the mill. A team of cheerful ladies provided morning coffee, hot midday meals and afternoon teas with homemade cakes and biscuits. Men and women sat at separate tables talking about football and politics, families and friendships. Weavers and warpers kept together, as did throwsters. Loom engineers – called tacklers – were a strong male clan in their oily overalls. The dyers, their aprons stained in many colours, another. But a shared camaraderie crossed divides of gender and trade; old hands teased the newcomers, and if they responded with good humour they became part of the gang.

Gwen wasn’t part of any gang, and seemed immune from canteen banter. We sat down at an empty table and she pulled off her turban, running her fingers through the ginger curls that corkscrewed round her head. Without her working woman’s armour she seemed more approachable.

‘Why haven’t we met before, Gwen? Were you brought up in Westbury?’

She shook her head, stirring three teaspoons of sugar into chocolate-brown tea.

‘How long have you lived here?’

‘Six years. Six happy years, mostly,’ she said, that rare smile lighting her face and giving me permission to ask more.

‘Whatever made you want to become a weaver?’ I said.

‘I started out wanting to be an artist. Went to art school. One thing led to another …’

I was intrigued. I’d never met anyone who had been to art school and, from what I’d heard, they were full of bohemians. But Gwen didn’t seem the type. ‘Golly. Art school? In London?’

‘It’s a long story,’ she said, stacking her teacup and plate. ‘Another time, perhaps.’

‘So what brought you to Verners?’ I persevered.

‘Your father, Lily.’ She paused, looked away, out of the canteen window towards the cricket willow plantation on the other side of the railway line. ‘He’s a very generous man. I owe him a lot.’ I felt a prickle of shame for not having appreciated him much. He was my Father, strict but usually kindly, rather remote when he was wrapped up in work. I’d never considered how others might regard him.

The squawk of the klaxon signalled the end of break-time. Over the loud scraping of utility chairs – the stackable sort of metal piping with slung canvas seats and backs – Gwen shouted, ‘Time to learn about the heart of the business, Miss Lily.’

After the peace of the packing hall, the weaving shed was a shock. As the door opened the noise was like running into a wall. Rows of grey-green looms stretched into the distance, great beasts, each in their own pool of light, a mass of complex oily iron in perpetual noisy motion – lifting, falling, sliding, striking, knocking, crashing, vibrating. How could anyone possibly work in this hellish metallic chaos?

The weavers seemed oblivious, moving unhurriedly between their looms, pausing to watch the material slowly emerge from the incessant motion of the shuttle beam, or stooping over a stilled machine. I quickly realised that they were skilled lip-readers and could hold long conversations in spite of the noise. But much of the time their eyes were focused intently on the cloth.

That first evening, John mocked me for falling asleep on the sofa and had to wake me for supper. As I prepared for bed I wondered what I would have been doing in Geneva. Getting dressed for a party, perhaps, or having hot chocolate and pastries in a café? For the moment I was too tired for regrets. Ears ringing, eyes burning, legs aching, my head full of new information, I wondered how I would get up and do the same again tomorrow.

The following day I was relieved to discover that we were spending it in the relative peace of the winding mill. Here, the silk skeins shimmered and danced as they rotated on their spindles releasing threads to be doubled, twisted and wound onto bobbins, and from bobbins onto pirns that would go into the shuttles. I learned the difference between the warp – the lengthways threads held taut between two rollers at either side of the loom – and the weft, the cross-threads woven into the warp from the shuttle.

Gwen no longer seemed so formidable. I was quickly learning to respect her skill and deftness, and her encyclopaedic knowledge of silk in all aspects of its complex manufacture. But she was still an enigma. Why would an educated woman like her choose to come and live in Westbury, to work in a mill?

I would find out soon enough.

Chapter Four (#ulink_e83b16bd-fe35-5aaf-9bd3-7d1017b6209e)

Another outstanding property of silk is its resilience, which can be demonstrated by crushing a silk handkerchief in one hand and a cotton handkerchief in the other. When released, the silk version will spring or jump upwards, the cotton one will stay crushed for some time. It is this property, along with its strength, toughness, elasticity and resistance to fire and mildew that makes silk so valuable for the manufacture of parachutes.

FromThe History of Silk,by Harold Verner

Long afterwards, John liked to embarrass me by claiming, sometimes publicly, that eight generations of weaving history had been rescued by his little sister’s sex appeal.

It’s true that Verners survived the catastrophe of war because of our contracts to weave parachute silk. While other mills folded or were converted into armament or uniform factories, we made it through, and came out the other side. But the invitation that arrived for John just a few months after I started work at the mill was really the start of it all. ‘It’s from my old school chum,’ he said, ripping open the heavy bond envelope with its impressively embossed crest. He proudly placed the gilt-edged card next to the carriage clock on the mantelpiece in the drawing room.

Mr John Verner and partner. New Year’s Eve, 1938. Black tie. Dinner and dancing 8 p.m., carriages 2 a.m. Overnight accommodation if desired, it read. Underneath was scrawled: Do come, Johnnie. Would be good to see you again. Marcus.

‘His ma and pa have a pile near the coast,’ he said. ‘They’re faded gentry but still not short of a bob or two. Should be a good bash.’ I was green with envy, of course. Vera’s latest bulletins from London had left me feeling very sorry for myself. She had discovered the ‘local’ next to the nurses’ home, met lots of dishy doctors and went to the flicks at least once a week. Even with Christmas coming up, my social calendar was blank, and I was bored stiff.

So I didn’t hesitate a single second when John said, a couple of days later, ‘Want to come with me to that New Year’s Eve bash, schwester? Dig out the old glad rags,’ he went on, ‘we both deserve a break.’ But I had no glad rags, at least nothing remotely passable for a sophisticated do. In the code language of formal invitations, ‘black tie’ meant women should wear ball gowns. Where would I find one of those in Westbury? And even if I could, how could I possibly afford it?

Then I remembered the blue-green shot silk that had so thrilled me on my first day at the mill, and asked Father if I could have a few yards as a Christmas present. I pored over fashion magazines, trying to imagine what style would make the most of my beanpole figure. It had to be modern, but formal enough to pass muster in ‘black tie’ company. At last I found the perfect pattern; the dress had a halterneck bodice that flowed into a wide full-length skirt to emphasise my waistline, and a bolero jacket for warmth.

In the days after Christmas Mother and I slaved over her old treadle sewing machine, and I endured countless pin-prickled fittings to get the dress just right. Now it was finished, and I barely recognised the elegant young woman looking back from the long mirror in my room. The cut of the gown and the shimmering silk made my figure, usually obscured in slacks and baggy jumpers at the factory, positively curvy.

My experiments with lipstick and mascara seemed to highlight interesting new features in a face I’d always considered plain. Even my straight brown bob seemed more sophisticated when I tucked the hair behind my ears to show off Mother’s emerald drop-earrings. We had fashioned a little clutch bag from scraps of leftover silk, and my old white satin court shoes – with low heels, I didn’t want to tower over any potential partner – had been tinted green by the dye works, to match the colour of the warp.

You’ll do, I thought, observing myself sideways, sticking out my chest and practising a coy, leading-lady smile. You might even get asked for a dance or two.

As we drove up the mile-long drive through acres of parkland and caught sight of the manor, my excitement gave way to apprehension. It was a red-brick Victorian gothic mansion with stone-arched windows, ornate chimneys and little turrets topping each corner of the building. Today I’d call it grandiose but at the time I was awestruck. The driveway was stuffed with smart motors: Jaguars, MG sports and Bentleys. John parked our modest Morris well out of view.

We were welcomed into a cavernous oak-panelled hallway by a real butler who led us upstairs to our rooms, carrying my case while I held the dress on its hanger before me like a shield. I feared I would never retrace our route as we trod endless gloomy corridors, taking frequent turns past dozens of identical doors.

My bedroom, when we finally reached it, seemed the size of a ballroom. It had once been very grand, I could see, but now the chintz curtains and bed coverlet were faded, and a miserly coal fire in a small grate made little impact on the overall chilliness. As I waited several minutes for a small stream of tepid water to emerge from the tap at the sink, I imagined the miles of piping it had to pass through to reach this distant room.

Shivering, I pulled on the dress and peered into the foxed glass of the mirror to apply my make-up, cursing as I dropped blobs of mascara onto my cheek. In the dim light of a single bulb hung from high in the ceiling I couldn’t be sure whether I’d managed to scrub it off properly.

But it was ten past eight and I couldn’t postpone the moment any longer. Tottering nervously through the maze of corridors, I lost my way several times. Eventually I found the top of the stairs and, having managed to negotiate these without tripping, followed the roar of voices to the drawing room. There, about forty people were knocking back champagne and talking at the tops of their voices, as if they had known each other for years.

I looked around urgently for John but he was nowhere to be seen. Instead, I found myself near a tall man holding court to three young women who waved their long cigarette holders ostentatiously and giggled a lot. With some alarm I noticed that the man was wearing what I at first took for a skirt but then realised was a Scottish kilt. I hugged myself into the corner against the wall, trying not to stare, and was greatly relieved when the gong sounded for dinner. Then, to my dismay, I noticed that the man in the skirt was smiling in my direction. The three girls glared as he walked over and offered his hand.

‘Robert Cameron, pleased to meet you. Would you do me the pleasure of accompanying me to dinner?’

‘Lily Verner, good evening.’ I said, as I returned the handshake and noted his startlingly blue eyes.

‘May I just say, Miss Verner, that dress is a stunner. Extraordinary colours. Silk, isn’t it?’ He took my arm and steered me firmly in the direction of the dining room. As we walked I stole a closer look; a kind of furry purse affair hung from his waist that I later learned was called a sporran. The kilt ended at the knees, and below that were hairy legs clad only in white socks, a small dagger stuffed into the top of one of them. It felt uncomfortably intimate being so close to those bare legs, and I barely dared imagine what he might or might not be wearing beneath those swinging pleats.

By the precision of his courtesies I guessed Mr Cameron had once been in the forces but wasn’t any more, not with those raffish sideburns. Slightly receding hair and deep smile lines suggested he was in his late twenties, and the high colour at his cheekbones and the small bulge above his crimson cummerbund seemed to evidence a life already well led.

‘And where have they been hiding you, Miss Lily Verner?’ he asked, helping me to be seated and then sitting himself beside me. I faltered, wishing I’d thought about this beforehand, planned what I would say. In this elevated company I could hardly admit I was an apprentice silk weaver.

‘Oh, I’ve been around,’ I answered airily, trying to sound sophisticated.

‘Then tell me where you found this beautiful gown,’ he persisted.

I tried to think of a posh London shop where they might sell ball gowns, but my mind went blank. Out of the blue, I decided to be completely honest. What did it matter, I’d never see any of these people again.

‘From our family’s silk mill,’ I said, ‘Verners, in Westbury. My father’s the managing director.’

I’d anticipated a blank look, or at least a swift change of subject, but to my great surprise Mr Cameron leapt to his feet, clipped his heels in a military manner, bowed deeply, picked up my hand and kissed it.

‘My goodness. Silk? How splendid. You look like a wee angel, but now here’s proof you’ve been sent from heaven, Lily Verner.’ Forty diners in the process of taking their places peered curiously at us between the silver candelabra, as I blushed to the tips of my ears. A few seats away on the opposite side, John raised his eyebrows: Are you all right with that man?

Mr Cameron sat down again. ‘You could be the answer to my prayers. Let’s get some wine and you can tell me all about it.’

‘There’s not such a great deal to tell,’ I said, overwhelmed by his display of enthusiasm. I wasn’t used to such effusive compliments.

‘Rubbish,’ he said robustly. ‘I want to know everything, from start to finish. And you absolutely must call me Robbie.’

He clicked his fingers at a waiter and barked an order for wine, then listened with great attention as, between sips of nondescript soup, I told him about the mill, the silk, where it came from, how we wove it, the trade we supplied. Feeling bolder by the minute, I even admitted that I worked there, adding quickly, ‘Just as a stopgap of course.’

‘How charming,’ he said, his face close to mine as he poured me another glass of wine, ‘a beautiful girl like you, working in a silk mill. That’s a new one on me.’

‘But now you must tell me about you,’ I said, feeling uncomfortable, ‘and why you are so interested in silk.’

As we washed down the main course of rubbery grey meat with liberal quantities of red wine, he explained that he had been born in Scotland – hence his entitlement to wearing a kilt – but had lived in England most of his life, was a cousin of our host, Johnnie’s school friend Marcus, and had been a guards officer until quite recently. But now he was dedicating his life – and, I guessed, a private fortune – to his two great passions: flying, and parachute jumping. A glamorous girl I’d noticed earwigging from the other side of the table chimed in, ‘Parachute jumping? Isn’t that rather dangerous?’

‘Of course, it used to be,’ he said, becoming more expansive with the added attention. ‘Those Montgolfiers and their French buddies back in the last century did a lot of experimenting with dogs. They didn’t always survive.’

‘Ooh, poor little poochies,’ she simpered, ‘that’s awfully mean.’

Most of the guests at our end of the table were now listening to the conversation. ‘Isn’t a parachute dangerous if you jump out of a moving plane? Wouldn’t it get tangled in the wings or the prop?’ asked a military-looking chap opposite.

‘Total myth, old man,’ said Robbie, ‘invented by the Air Ministry. They were dead scared that fliers might jump and dump expensive chunks of ironware before it was absolutely necessary. But they’ve finally accepted that parachutes save lives, if they’re the right kind.’

‘Is there a wrong kind?’ I found myself genuinely curious.

‘Lord, yes. Parachutes that collapse in the middle, that get pushed in by wind, lines that tangle, packs that don’t unfurl quickly enough. The design is critical.’ He paused and took a long sip of wine, carefully wiping his lips with the napkin. His audience was waiting. ‘But the most important thing is the silk. It has to be just right. Not too thick, not too thin, not too porous, not too impervious.’ Then he turned to me and lowered his voice, ‘Which is why, Miss Verner, I would like to have a serious conversation about silk with your father and brother – and you too of course – at some point very soon.’

‘We’d be delighted,’ I said, glowing in his attentiveness and flattered to be included, ‘but if I am to call you Robbie, you must stop calling me Miss Verner. Call me Lily, please.’

‘So, lovely Lily,’ he said, refilling my glass, ‘have you ever flown in a plane?’

‘Er … no,’ I stuttered nervously, ‘I’m not sure it’s my sort of thing.’

‘Would you like to give it a try? We could go for a spin.’

‘Perhaps, but can I finish my dinner first?’

He laughed generously, and as dessert was served I became vaguely aware of music coming from a distant room. ‘Can you hear the band, Miss Lily Verner? I’ll wager you’re a good dancer. Hope you like Swing.’

I smiled and said nothing, to conceal my ignorance.

‘Watch out for that one, Sis. Looks like a bit of a rogue and too old for you, anyway,’ John whispered as we left the dining room. But I didn’t care. The wine made me daring and confident, and I was determined to enjoy myself.

After a couple of rather sedate waltzes, Robbie went over and spoke to the bandleader. With broad smiles on their faces, the musicians switched pace and started to play a very fast jazzy number. He pulled me out onto the floor and started to dance like a wild thing, kicking his legs so high I barely dared look in case the skirt flew up too. He gestured to me to do the same, swinging me from side to side and twirling me around. It was exhilarating, dancing so freely, to such irresistible rhythms.

‘It’s the Lindy Hop,’ he shouted over the music. ‘Just come over from America. Named after Charlie Lindbergh. Fun, eh?’

I’d never heard of the man but it certainly was fun, if rather absurd, dancing like this in our formal gowns and dinner jackets, in a country house ballroom with its bright merciless light glittering from chandeliers and mirrors. It was impossible to keep still, and we Lindy Hopped right through until midnight, when the band reverted to Scottish tradition and we welcomed in the New Year with ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

After champagne toasts to ‘a peaceful 1939’, Robbie proved equally accomplished at quicksteps and foxtrots, guiding me firmly across the floor and spinning me round at every opportunity. It felt so safe in his arms, and it was so easy to be graceful, that I was disappointed when the band stopped and the dancers started to drift away.

Robbie escorted me to the foot of the stairs with his arm fitted snugly around my waist.

‘Goodnight, Miss Lily Verner.’ He put a finger to my chin, tipped my face upwards and pinned his lips to mine. My first kiss. I’d expected it to be more exciting, but it just felt a bit awkward, and after a polite pause I pulled away.

‘I’ve had a lovely evening, but I must go to bed now,’ I gabbled.

He was unabashed. ‘You’ve already made it very special, you sweet thing. Sleep tight. See you in the morning.’ He kissed my nose this time, and patted my backside as I turned to run up the stairs. As I climbed into my chilly bed, churning with champagne and confusion, I wondered if I might be falling in love.

Next day we were eating breakfast in proper country-house style – bacon, eggs, kedgeree and kippers served on ornate silver hotplates casually arrayed on the antique sideboard – when we heard the sound of an aircraft flying low over the house.

A small bi-plane came into view, circling twice, each time lower than before, and John said, ‘Crikey. Look Lily, he’s coming in.’

Sure enough, to our astonishment the plane flew even lower and then landed bumpily on the parkland between the trees, scattering the peacefully grazing flocks of deer.

‘It’s just Robbie showing off again,’ said Miranda, our host’s sister, to whom we’d been introduced the night before. Sure enough, as the plane drew to a halt, we saw his leather-clad figure emerging from the cockpit, jumping down and starting to lope towards the house. Before long he was helping himself to a hearty plateful of kedgeree and joining us at the table.

‘Flying make you hungry?’ John said casually, as if this kind of arrival at breakfast happened every day in our family.

‘Ravenous.’ Robbie shook clouds of pepper over his plate. ‘I’ve been up since six.’ We chatted for a while about last night, what fun it had been, and then he turned to John and said, almost offhand, ‘Lovely day for a spin, old man. Care to join me? She can take a co-pilot and a passenger. Perhaps Lily would like to come too?’

‘That’d be cracking,’ John said, his face lighting up.

I panicked. ‘Not for me, thank you. I haven’t got anything warm to wear. Anyway, don’t you think we should be getting home, John?’

‘I’d really like to go,’ he said. ‘Come on, sis. You’re always moaning about life being boring. Have a bit of fun. When are you going to get a chance like this again?’