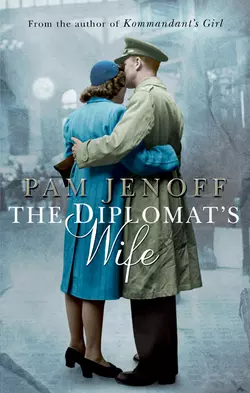

The Diplomat′s Wife

Пэм Дженофф

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING TITLE THE ORPHAN′S TALE OUT NOWHow have I been lucky enough to come here, to be alive, when so many others are not? I should have died. . . . But I am here.1945. Surviving the brutality of a Nazi prison camp, Marta Nederman is lucky to have escaped with her life. Recovering from the horror, she meets Paul, an American soldier who gives her hope of a happier future. But their plans to meet in London are dashed when Paul′s plane crashes.Devastated and pregnant, Marta marries Simon, a caring British diplomat, and glimpses the joy that home and family can bring. But her happiness is threatened when she learns of a Communist spy in British intelligence, and that the one person who can expose the traitor is connected to her past.Praise for Pam Jenoff:‘[A] heartbreakingly romantic story of forbidden love during WW2’ – Heat‘Must read’ – Daily Express