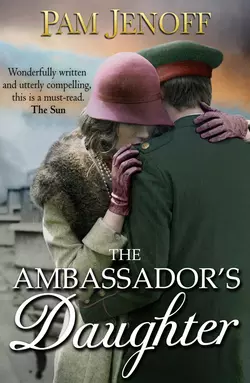

The Ambassador′s Daughter

Pam Jenoff

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING TITLE THE ORPHAN'S TALE OUT NOWParis, 1919The nation’s leaders have gathered to rebuild the world from the ashes of The Great War. But for one woman, the City of Light harbours dark secrets and dangerous liaisons Brought to the peace conference by her German Diplomat father, Margot resents being trapped in Paris where she is still looked upon as the enemy.Yet returning to Berlin means a life with the wounded fiancé she barely knows. Torn between duty and the desire to be free, Margot strikes up unlikely alliances: with Krysia, a musician who protects a secret; and with Georg, the handsome, damaged naval officer who makes Margot question where her true loyalties should lie.Against the backdrop of one of the most significant events of the century, a delicate web of lies obscures the line between the casualties of war and of the heart, making trust a luxury that no one can afford.THE STUNNING PREQUEL TO THE BESTSELLING NOVEL, KOMMANDANT’S GIRL, HERALDED A ‘BREATHTAKING DEBUT’ BY PUBLISHERS WEEKLY‘Wonderfully written and utterly compelling, this is a must-read’ – The SunPraise for Pam Jenoff:‘ heartbreakingly romantic story of forbidden love during WW2’ – Heat‘Must read’ – Daily Express

Praise for the author

Quill Award Nominee

‘This is historical romance at its finest.’

—Publishers Weekly on Kommandant’s Girl

‘In her moving first novel, Jenoff offers an insightful portrait of people forced into an untenable situation and succeeds in humanizing the unfathomable as well as the heroic.’

—Booklist

‘Poignant and intense’

—Good Book Guide on The Diplomat’s Wife

‘Jenoff explores the immediate aftermath of World War II with sensitivity and compassion, shedding light on an often overlooked era of European history. She expertly draws out the tension and illustrates the danger and poverty of Eastern Europe as it falls under communism. Highly recommended for all fiction collections.’

—Library Journal on The Diplomat’s Wife

‘… well constructed and a real page turner.’

—Birmingham Jewish Weekly on The Diplomat’s Wife

About the Author

PAM JENOFF is the author of several novels, including the international bestseller Kommandant’s Girl, which also earned her a Quill Award nomination. Along with a bachelor degree in International Affairs from George Washington University and Master’s degree in History from Cambridge, she received her Juris Doctor from the University of Pennsylvania and previously served as a Foreign Service Officer for the US State Department in Europe, as the Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Army at the Pentagon and as a practising attorney. Pam lives with her husband and three children near Philadelphia where, in addition to writing, she teaches law school.

Also byPam Jenoff

KOMMANDANT’S GIRL

THE DIPLOMAT’S WIFE

The

Ambassador’sDaughter

Pam Jenoff

In loving memory of Dad

Acknowledgments

The Ambassador’s Daughter represents joy on so many levels to me. First, it gave me the chance to return to some of my beloved characters and themes from Kommandant’s Girl, something that I—and many of my readers—have been hoping would happen for several years. It also allowed me to explore Europe after the First World War, an era that has fascinated me since I wrote about it in my thesis at Cambridge nearly two decades ago. Writing a story in this era required extensive research about historical events as well as the social and political climate at the time. As always when writing historical fiction, I had to make some judgment calls about when to remain historically accurate and when to “bend” history, melding fact and fiction for the sake of story (a creative indulgence for which I hope my readers will forgive me).

This book brought me back to the incomparable publishing team at HQ, including my wonderful editor, Susan Swinwood, and the many brilliant folks in editorial, marketing, publicity and sales, and Kim Young and the marvelous team at HQ. I am so grateful for your time and talents, and overjoyed to be working with you again! Big thanks as always to my agents Scott Hoffman and Michelle Brower at Folio Literary Management for all of your keen insight and tireless work on my behalf. Thanks also to my colleagues at Rutgers for your interest and support.

Even as it is joyous, writing this book has been bittersweet. When I began The Ambassador’s Daughter, a book that examines among other things the parent-child relationship, I had no idea that my own beloved father would not be here to see the finished project. With each book I always recognize the “village” that makes my writing life possible. However, this time I need to express even more deeply my gratitude for those closest to me: my husband, Phillip, mother, Marsha, brother, Jay, as well as my in-laws Ann and Wayne, dear friends, and of course, the three little muses who sustain and inspire me every day, Benjamin, Charlotte and Elizabeth. I love you all.

PROLOGUE

The sun has dropped low beneath the crumbling arches of Lehrter Bahnhof as I make my way across the station. A sharp, late-autumn breeze sends the pigeons fluttering from the rafters and I draw my coat closer against the chill. The crowds are sparse this Tuesday evening, the platforms bereft of the usual commuter trains and their disembarking passengers. A lone carriage sits on the track farthest to the right, silent and dark.

I had been surprised by the telegram announcing Stefan’s return by rail. There were hardly any trains since the Allies had bombed the lines. At least that’s what the newspapers write—the defunct trains and the British naval blockade are the excuses given for everything, from the lack of new pipes to start the water running again—a problem that has forced us back outside as though it were a century ago—to the impossibility of getting fresh milk. Looking around the desolate station now, I almost believe the excuse.

Stefan’s face appears in my mind. It was more than four years ago on this very platform that we said goodbye, the garland of asters I’d picked hung freshly around his neck. “Don’t go,” I pleaded a final time. Stefan was not cut out to fight—he had a round, gentle face, wide brown eyes that said he could never hurt anybody. But it was too late—he had gone down to the enlistment center two weeks earlier, ahead of any conscription, and come home with papers ordering him to report. The war was going to be quick, everyone said. The horse-mounted Serbs, with their swords, were no match for the Kaiser’s tanks and planes. The fighting would be over in weeks, and all of the boys wanted a piece of the glory before it was gone.

I peer back over my shoulder past the closing kiosk, which gives off the smell of stale ersatz coffee, at the station doors, creaking open and closed with the wind. Someone more important than me should have been here to meet Stefan. He is a soldier, wounded in battle. More to the point, he is the only young man from our Jewish enclave in Berlin who had gone off to fight and come back at all. I don’t know what I expected, not a marching band and reporters exactly, but perhaps a small delegation from the local war council. The once-proud veterans’ group had been disbanded, though. No one wanted to be identified as a soldier now, to face the glares of reproach and the questions about why they had not gotten the job done.

Fifteen minutes pass, then twenty. I clutch tighter the fine leather gloves that I’ve managed to twist into a damp, wrinkled ball. Fighting the urge to pace, I start toward the station office to inquire if there is news of the next arrival. I navigate around a luggage trolley, which has been upended and abandoned midstation. My skirt catches on something and I pause, turning to free the hem. It is not a nail or board, but a filthy, long-haired man sitting on the ground, a fetid mass of bandages where his right leg had once been.

“Bitte …” a voice rasps as I jump backward. “I’m sorry to startle you.” He is a soldier, too, or was, his tattered uniform barely recognizable. I fish a coin from my purse, trying not to recoil from the hand that reaches out for it. But inwardly, I blanch. Will Stefan look like this sorry creature?

I lift my head as a horn sounds long and low from the darkness beyond the edge of the station. A moment later a train appears, threading its way onto one of the tracks. It moves so slowly that it seems to have no engine at all, nudged instead by some slight tilt of the earth. Great clouds of steam billow from its funnel, filling the station. As I walk toward the platform, straining to see through the mist, my heart begins to pound.

The train grinds to a halt. The doors open with painstaking slowness and a few men spill out, some in uniform and others street clothes. I search those walking toward me for Stefan, knowing that he will not be among them.

When the platform has nearly cleared, a nurse pushes a wheelchair from one of the train carriages. I step forward, and then stop again. The chair does not contain Stefan, but an elderly man, hunched over so only the top of his bald head shows. The nurse struggles with the chair and as its rear wheels catch on the door, I hasten to help her.

The man in the chair uncurls, straightening slightly as I near. It is Stefan, I realize, biting my lip so hard I taste blood. A giant slash across the right side of his face from temple to chin combines with the lack of hair to make him almost unrecognizable. But the worst part is his arms, skeletal and shaky. My mind races as I try to fathom the horrors that could age a man decades in a few years.

Stefan gazes up with vacant, watery eyes, not speaking. “Hello, darling,” I manage, bending to brush my lips against his papery cheek.

He reaches for me with a quivering hand. “Let’s go home,” he croaks, and as his fingers close around my wrist like cold death, I let out the cry I can hold back no longer.

My eyes fly open and I sit up in the darkness, still screaming.

PART ONE Paris, December 1918

1

I cycle through the Jardin des Tuileries, navigating carefully around the slippery spots on the damp gravel path. The December air is crisp with the promise of snow and the bare branches of the chestnut trees bow over me like a procession of sabers. I pedal faster past the park benches, savoring the wind against my face and opening my mouth to gulp the air. A startled squirrel darts behind the base of a marble statute. My hair loosens, a sail billowing behind me, pushing me farther and faster, and for a moment it is almost possible to forget that I am in Paris.

The decision to come had not been mine. “I’ve been asked to go to the peace conference,” Papa informed me unexpectedly less than a month ago. He had previously professed no interest in taking part in “the dog and pony show at Versailles,” and had harrumphed frequently as he read the details of the preparations in the Times. “Uncle Walter thinks …” he added, as he so often did. I did not need to listen to the rest. My mother’s older brother, an industrialist who had taken over the electronics firm their father founded, could not attend the peace conference himself after contributing so much to the war machine. He considered it important, though, to somehow have a voice at the table, a presence before the Germans were formally summoned. So he had secured an invitation for Papa, an academic who had spent the war visiting at Oxford, to advise the conference. It was important to be there before Wilson’s ship arrived, Papa explained. We packed up our leased town house hurriedly and boarded a ferry at Dover.

Papa had not been happy to come, either, I reflect, as I reach the end of the park and slow. The street is choked thick with motorcars and lorries and autobuses, and a few terrified horses trying to pull carriages amid the traffic. He had pulled forlornly on his beard as we boarded the train in Calais, bound for Paris. It was not just his reluctance to be torn from his studies at the university, immersed in the research and teaching he loved so, and thrust into the glaring spotlight of the world’s political stage. We are the defeated, a vanquished people, and in the French capital we loved before the war, we are now regarded as the enemy. In England, it had been bad enough. Though Papa’s academic status prevented him from being interned like so many German men, we were outsiders, eyed suspiciously at the university. I could not wear the war ribbon as the smug British girls did when their fiancés were off fighting, because mine was for the wrong side. But outside of our immediate Oxford circle it had been relatively easy to fade into the crowd with my accentless English. Here, people know who we are, or will, once the conference formally begins. The recriminations will surely be everywhere.

My skirts swish airily as I climb from the bike, thankfully free of the crinolines that used to make riding so cumbersome. The buildings on the rue Cambon sparkle, their shrapnel-pocked facades washed fresh by the snow. I stare up at the endless apartments, stacked on top of one another, marveling at the closeness of it all, unrivaled by the most crowded quarters in London. How do they live in such spaces? Sometimes I feel as though I am suffocating just looking at them. Growing up in Berlin, I’m no stranger to cities. But everything here is exponentially bigger—the wide, traffic-clogged boulevards, square after square grander than the next. The pavement is packed, too, with lines of would-be customers beneath the low striped awning of the cheese shop, and outside the chocolatier where the sign says a limited quantity will be available at three o’clock. A warm, delicious aroma portends the sweets’ arrival.

A moment later, I turn onto a side street and pull the bike up against the wall, which is covered in faded posters exhorting passersby to buy war bonds. A bell tinkles as I enter the tiny bookshop. “Bonjour.” The owner, Monsieur Batteau, accustomed to my frequent visits, nods but does not look up from the till.

I squeeze down one of the narrow aisles and scan the packed shelves hungrily. When we first arrived in Paris weeks earlier, it was books that I missed the most: the dusty stacks of the college library at Magdalen, the bounty of the stalls at the Portobello Road market. Then one day I happened upon this shop. Books had become a luxury few Parisians could afford during the war and there were horrible stories of people burning them for kindling, or using their pages for toilet paper. But some had instead brought them to places like this, selling them for a few francs in order to buy bread. The result is a shop bursting at the seams with books, piled haphazardly in floor-to-ceiling stacks ready to topple over at any moment. I run my hand over a dry, cracked binding with affection. The titles are odd—old storybooks mix with volumes about politics and poetry in a half-dozen languages and an abundance of war novels, for which it seems no one has the stomach anymore.

I hold up a volume of Goethe. It has to be at least a hundred years old, but other than its yellowed pages it is in good condition, its spine still largely intact. Before the war, it would have been worth money. Here, it sits discarded and unrecognized, a gem among the rubble.

“Pardon,” Monsieur Batteau says a short while later, “but if you’d like to buy anything …” I glance up from the travelogue of Africa I’d been browsing. I’ve been in the shop scarcely thirty minutes and the light outside has not yet begun to fade. “I’m closing early today, on account of the parade.”

“Of course.” How could I have forgotten? President Wilson arrives today. I stand and pass Monsieur Batteau a few coins, then tuck the Goethe tome and the book on botany I’d selected into my satchel. Outside the street is transformed—the queues have dissipated, replaced with soldiers and men in tall hats and women with parasols, all moving in a singular direction. Leaving the bike, I allow myself to be carried by the stream as it feeds into the rue de Rivoli. The wide boulevard, now closed to motorcars, is filled with pedestrians.

The movement of the crowd stops abruptly. A moment later we surge forward again, reaching the massive octagon of the Place de la Concorde, the mottled gray buildings stately and resplendent in the late-afternoon sun. The storied square where Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI were executed is an endless mass of bodies, punctuated by the captured German cannons brought here after the armistice. The statues in the corners, each symbolizing a French town, have been covered in laurels.

The crowd pushes in behind me, onlookers from every side street attempting to pack the already choked space. I am surrounded by a sea of tall men, the damp wool from their coats pressing against my face, making it impossible to breathe. Close spaces have never suited me. Trying not to panic, I squeeze through to one of the cannons. I hitch my skirt and climb onto the wheel, the steel icy against my legs through my stockings. “Pardon,” I say to the startled young man already on top of the gun.

There are flags everywhere, I can see from my new vantage point, banners unfurled from the balconies of the columned Hôtel de Crillon, American flags in the hands of the children. “Wilson the Just!” placards declare. A lane has been formed through the square, roped off with great swaths of sky-blue cloth to keep the crowd back. Airplanes, lower and louder than I’ve ever heard, roar overhead.

A few feet to the right of the cannon, a woman in a blue cape catches my eye. Nearly forty by the looks of her, she stands still in the feverish crowd. She is tall, her posture perfectly erect, with chestnut-brown hair piled upon her head. She is somehow familiar, though from where I cannot say. Abruptly, she turns and begins walking, swimming against the tide, slipping away from the gathering. Who would leave before Wilson’s arrival? Surely there is nowhere else to be in the city now. I wonder fleetingly if she is ill, but her movements are calm and fluid as she disappears into the crowd.

The din grows to a roar. I turn my attention back to the square as a row of mounted soldiers canters into view, wearing the bright helmets of the Garde Republicaine. The horses raise their heads high, snorting great clouds of frost from their flared nostrils. The crowd pushes in, twisting the once-straight lane into a serpentine. I shudder as unseen guns erupt jarringly in the distance. Surely that is not a sound any of us needs to hear anymore.

Behind the horses, a procession of open carriages appears. The first bears a man in a long coat and top hat with a woman beside him. Though it is too far away for me to see, I can tell by the whoops that he is President Wilson. As the carriage draws closer and stops in front of the hotel, I recognize Wilson from the photos. He waves to the crowd as he climbs down. But his bespectacled face is solemn, as if seeing for the first time the hopes of so many that hang on his promises.

A minute later Wilson disappears into the hotel. The show quickly over, the onlookers begin to ebb, bleeding down the dozen or so arteries that lead from the square. I glimpse the woman in the blue cape, several yards away now, still fighting her way through the crowd. Impulsively, I hop down from the cannon, catching the hem of my skirt as I do. I free the material, then push toward her, weaving through narrow gaps, heedless now of the closeness as I follow the flash of blue like a beacon.

As I reach the street, I spy the woman fifty or so meters ahead, turning into the park where I’d been cycling an hour earlier. There is nothing unusual about that. But one would not have left Wilson’s arrival for a stroll and her gait is purposeful, suggesting an errand more interesting than just fresh air. I push forward, following her into the park. A moment later, she turns off the main path into a smaller garden where I’ve not been before.

I pause. A gate, tall and tarnished, marks the entrance, elaborate lions carved into either side standing sentry. Ahead, the path is obscured by winter brush. Turn back, a voice seems to say. But the woman in blue has disappeared at a turn in the bend and I cannot resist following her.

I step through the gate and into the garden. A few meters farther, the path ends at a small, frozen pond, dividing to follow its banks on either side. I scan the deserted park benches, but do not see the woman. From beyond the bend comes the sound of laughter. I follow the path as it curves around the pond and it opens to reveal a wide expanse of frozen water, nestled in a cove of trees. A group of well-dressed young women in their late teens, perhaps a year or two younger than me, skate on the ice, chatting in loud, carefree voices.

Across the pond, something stirs against one of the trees. The woman in blue. Will she join the skaters? Maybe two decades older, she appears an odd fit, but the conference has brought together all sorts of unusual people, blurring the conventions and distinctions that might have separated them back home. The woman hangs in the shadows, like the witch out of a fairy tale, watching the skaters raptly. Her gaze is protective and observant, a scientist studying a subject about which she really cares.

The skaters start for the bank and the woman in blue steps back, disappearing. I consider following her farther, but the sun has dropped low behind the trees, the early winter afternoon fading.

Twenty minutes later, having retrieved my bike, I reach the hotel. Papa chose our lodgings at the tiny Hôtel Relais Saint-Honoré carefully. Just across the river from the foreign ministry, it keeps him close to the conference proceedings while still maintaining a bit of privacy. The lobby, with its cluster of red velvet chairs in the corner, feels more like a parlor.

“Mademoiselle,” the desk clerk calls as I cross the lobby. I turn back reluctantly. He holds out a letter toward me, between his thumb and forefinger, as though the German postmark might somehow be infected. I reach for it, my stomach sinking as I eye the wobbly script.

I start for the elevator once more. As the doors open, I am confronted unexpectedly by Papa and two men with swarthy complexions and dark mustaches. “And if you look at the prewar boundaries …” Papa, speaking in French, stops midsentence as he sees me. “Hello, darling. Gentlemen, may I pre sent my daughter? Margot, these are Signore DiVin-cenzo and Ricci of the Italian delegation.”

“A pleasure,” I say. They nod and stare at me strangely. It is my dress, soiled and torn at the hem from where I caught it on the cannon, as well as my disheveled hair. I may quite possibly smell, too, from my vigorous bike ride through the park.

But Papa does not seem to notice, just smiles a warm mix of affection and pride. “I’ll be up in a moment, my dear.” It is not just that he is an absentminded academic—Papa has always accepted me wholly as I am, with all of my rough spots and imperfections. He is not bothered by my unkempt appearance, any more than I mind his predisposition to forgetting about meals or the days of the week.

The attendant closes the elevator gates and my stomach flutters in the queer way it always does as we ride upward to the third floor. I unlock the door to our suite, which consists of a bedroom each for Papa and me, adjoined by a sitting room. I go to the washroom and run the water in the large, claw-foot tub, then pour in some salts. As the tub fills, I remove my soiled dress and the undergarments that have etched themselves to my body. Crinolines may have gone out of style but corsets, unfortunately, are another matter. I turn off the tap and slip into the deep, warm bath, grateful to be enveloped by the steam.

Thinking of the unopened letter, Stefan’s face appears. It is hard to remember exactly when we became romantically involved. He had always been present—a boy on the neighboring block and in the class a grade above mine across the hallway at school. We had played together often as children and he’d been beside me at my mother’s funeral, taking my hand and helping me slip away from the crowded house after. One autumn morning when I was fifteen and reading on the front step of our home in Berlin, Stefan rode by on his bicycle, slowing but not quite stopping as he passed. This did not strike me as unusual—he had a paper route delivering the Post to the houses on our block that ordered it. Half an hour passed and he circled again. I looked up, my curiosity piqued. Stefan’s house was around the corner on a nicer block than ours, twice as big but with a drooping roof and cracked steps in need of repair. I’d seen him on our street three or more times a day lately, though the paper came only daily.

“Wait,” I called after him, standing up. He stopped abruptly, grabbing the handlebar to stop the bike from lurching sideways. “Did you want something?”

He climbed off the bike and set it down at the curb then walked over to me. There was something different about him. Though his strawberry-blond hair and pale skin were the same, he had started shaving, the peach fuzz that had once adorned his upper lip now a faint stubble. He had shot up in height and stood several inches above me and there was a new thickness to his arms.

“I was wondering,” he said, “if you’d like to go to the movies.”

I averted my eyes, caught off guard. I’d expected an invitation to join the football game the boys played Sundays in the park, though Tante Celia said I was getting too old for such things. But his tone was different now and when I turned back to him, I noticed that perspiration soaked his collar. He was nervous.

“Yes,” I say hurriedly, wanting to ease his discomfort.

“I’ll call for you tonight at seven.” He stepped backward, nearly tripping over his bike before getting on and racing away.

The night at the movies was unremarkable, an American comedy, followed by an ice cream at the Eiscafé. After that day, Stefan became increasingly present, coming by the house after school, joining us for Sunday lunch at Uncle Walter’s villa in Grunewald. One afternoon as we strolled around the lake behind the villa, I looked down at our hands, fingers intertwined, and realized that we were courting. Not that it was so very different from when we had just been friends. Stefan was unobtrusive and left me to my own devices. Being with him was rather like being with myself.

We were at Uncle Walter’s for Sunday lunch when news of the war came. One of his aides rushed into the dining room and whispered in his ear and he broke the usual quiet by turning on the radio that sat on the mantelpiece. The men nodded with approval as Germany’s declaration of war crackled over the airwaves. Our ally Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated, murdered in broad daylight by a heathen Serb. We had to take a stand.

Ten minutes later, I climb from the tub, still thinking of Stefan as I dry and put on a fresh dress. I could have gone back to Berlin after the war, insisted that Papa allow me to be with Stefan as he recovers. But I had not. I swallow against my guilt. He is well cared for by his family. It is me he wants above all else, though, I can tell from his letters, which always speak excitedly of my return. I have sent packages of French jellies and other delicacies, but answering his letters is harder. What can I say to this man I hardly know anymore?

I rummage through my toiletries for some salve to relieve my hands, which have grown dry and chapped from the air here. It is my insistence on taking off my gloves too often, Tante Celia says. The items in my kit are few—some face powder, a single tube of pale pink lipstick for special occasions, a fragrance that Celia had given me for my birthday last year, too flowery for my taste.

By the time I emerge, Papa has returned, shuffling papers at the rolltop desk in the corner that doubles as his study over a glass of Pernod. Dinner, two plates covered by metal domes and a thick loaf of bread wrapped in cloth, sits un-served as is our preference.

“Papa,” I say gently, nudging him from his work. I bring the candlesticks down from the mantelpiece as he pours the wine. “Baruch atah Adonai …”

“Celia is at a reception,” he says without my asking when we’ve finished the blessings. I exhale slightly. I would not have been uncharitable and turned away kin with nowhere to go. But spending each Sabbath together is a tradition that Papa and I have observed wherever we have been in the world, bringing our silver Kiddush cup and candlesticks with us, and we continue it here in Paris. No matter how busy he is, Papa always stops what he is doing so that we can have a meal and talk, just the two of us.

I cut the crusty, still-warm loaf of bread. Living in the hotel, it is easy to forget about the shortages the outside world still endures. I hand Papa a piece and notice then that his face is pale. Though he is immaculately dressed and groomed as always, a trim sliver of silver hair circling his head, there are dark circles around his eyes. “Have you taken your medicine?” I ask gently. He gets so caught up in his work that he can forget to eat or sleep much less to take the pills that the doctor said are important for his heart condition. I’ve been reminding him for as long as I can remember.

Before he can answer, I sneeze once, then again. “It’s the dry air,” I say hastily, reaching for my handkerchief. Papa’s brow wrinkles with consternation, now his turn to worry about me. Spanish flu, like the one that had taken my mother more than a decade ago, has been on the rise since autumn. Though I had also come down with the flu as a child, it had spared me like the angel of death in the Passover story, passing by as if lamb’s blood had been painted on the door. I had labored with a fever for days. Then I’d awakened with a permanent crescent-shaped scar on my neck, a reaction to one of the medicines.

But this new flu strain is even more virulent, having taken twelve lives at Oxford alone before our departure. People talked endlessly about how to prevent it—wash out the nose with warm water and soda, wear garlic around the neck, drink a shot of whiskey before bedtime. Some whispered that the Germans unleashed it as a weapon of war, stopping just short of blaming me and Papa personally. “More likely,” Papa said once, “it came across the Atlantic with the soldiers.” In London, people had all but stopped going out. But here the parties continue on gaily, as if germs were some invention of the science fiction writers.

I sample a spoonful of the rich coq au vin. “I’m fine, really. Tell me about your day.”

As we eat, Papa describes his meeting with the men from the Italian delegation, who are seeking his support for an independent Macedonia. “And then there are the West African colonies,” he says, jumping topics as always with mercurial speed. “The French are going to put up a fight on granting independence. They want mandates instead.”

“So it is only to be self-determination for some.”

“Liebchen, we must be practical. One cannot change the entire world in just a few months.”

Then what is the point of the conference? I wonder. “We have to work within the system,” he adds, as if responding to my unspoken question. “Though I know you do not agree. Enough about my work,” he says, as I clear the plates and set out coffee and apple cake. “How are you, my dear?”

“Fine. A bit restless.”

“Oh? I thought you and Celia might enjoy some of the museums….” His voice trails off and he winces at the gulf between me and mother’s sister, a woman he dearly wishes I would accept. “Perhaps if you had a brother or sister,” he frets, as he has so many times over the years. Small families like ours are the exception rather than the rule but, for some reason not quite clear to me, siblings had not been possible.

I kiss his cheek. “I would not have cared to share you,” I say, trying to assuage his guilt. It is the truth. The two of us have always been enough. I see then our Sabbath meals as a tableau, a scene that has played itself out in various cities over the years. “And I’m fine, really. The parties are all well and good, but the women are just silly.” I stop, hearing myself complaining again.

“Would you be happier outside the city?” Papa asks.

I contemplate the question. I have always felt freest when close to nature, like on the hiking trips we took when I was a child. Papa, despite being bookish, had an amazing capacity for the outdoors, an ability to navigate the densest forest without a compass, to find fresh water and sense the weather that was coming. We would climb high with a day’s food in our packs and stay in the cabins that populated the high hills, reaching the next before sundown.

But Paris, while cramped, has a certain energy. And I don’t want to be exiled to some boring suburb with Tante Celia. “I don’t know. I don’t think so, anyway.”

It isn’t the city itself that I dislike, I decide as we eat dessert. I came here every spring as a child, shopping the fine boutiques of Faubourg Saint-Honoré with my mother until Papa joined us at the end of the day for cakes at one of the patisseries. I’d even dreamed of one day studying at the Sorbonne.

No, it’s Paris now that I hate. On the eve of the conference, the city is bursting at the seams with journalists and delegates from every conceivable cause and country. Hotels empty since before the war have been aired out, their rooms hastily refreshed to accommodate everyone who has come to the show. I don’t mind those who have cause to be here, the stuffy clusters of suited men who will decide the future of the world, the scrappy delegates from countries seeking to be born. But the hangers-on, the socialites and doyennes that have come to provide the parties and other window dressing, having stifled Paris to the choking point.

“Well, the question will be out of our hands at some point. When the Germans arrive,” he says. My brow wrinkles. We are the Germans. “The official delegation, I mean, we’ll be expected to go out to Versailles where they are to be housed.”

I consider this new bit of information. The conference proceedings are being held in Paris, but the Germans will be housed outside in Versailles. The site where the Germans had imposed their draconian peace terms on France a half-century earlier, it is now where we are to get our just deserts. “Are the conference proceedings to move out there when the delegation arrives?”

“Not that I’m aware.”

“But one would think, if the Germans are to participate in the conference that they should be near the meetings….”

“One would think.” He pauses for a sip of coffee. “One would think that they would have invited the German delegation here for the early months of the conference if they were really to participate.”

How could one negotiate peace without the other side at the table? “Are you familiar with the delegation?” I ask.

“Oh, the usual sorts. Rantzau—he’s the new foreign minister—as well as the defense minister and the ambassador, of course, Uncle Walter’s old nemesis.” The men in power form a very tight club, raised in the same circles and educated at the same schools. It was a club to which Papa had never wanted to belong, but now he had found himself drawn back in by the conference. “There’s a younger fellow, too, a military captain, but I can’t recall his name.”

“Are they bringing anyone with them? Families, I mean?”

Papa shakes his head. “Hotel accommodations are quite limited in Versailles.” It was unusual for delegates, even from the victorious countries, to bring their wives and children. “You still haven’t told me what you’ve been up to today, other than avoiding Tante Celia.”

I consider mentioning the woman in the blue cape, but even in my head it sounds inconsequential, my own interest silly. “I saw Wilson’s arrival today,” I say instead.

“Oh?”

“The crowd was most receptive.”

“They have such high hopes. The Fourteen Points, self-determination, a new world order …” He shakes his head. “Wilson is idealistic. It’s like the notion in Judaism—tikun olam means, quite literally, to repair the world. That’s what he is trying to do.”

“You don’t think he will be able to do it.”

“I think it isn’t that simple.” He picks up his pipe, but does not light it, instead waving it like a pointer in a lecture hall. “Take self-determination for example. What does that mean? Who is the self—a nationality, a religious group or something altogether different?” He jabs at the air in front of him. “Do I believe they will make a difference or reshape the world? I don’t know. The world will never go back to what it was—kaisers and czars and kings, but the question is whether we can make something better in its place. I believe the world will be a better place for the trying.” He sighs. “Anyway, you’ll get to see a bit more of Wilson at the welcoming reception tomorrow night.” I cock my head. “I mentioned it to you last week.” The social calendar had been so full with stuffy affairs, I’d stopped listening, rather allowing Papa and Celia to lead me where needed. “It should be quite the occasion.”

I groan. “Must I attend?”

“I’m afraid so. It is an important event and it wouldn’t do for us to miss it. You’ve heard from Stefan?” he asks, changing the subject again. Papa has allowed me much liberty as a young woman, but on this one point he pushes. He is nearly seventy now, and eager to see me settled, rather than left alone in the world.

“I have.” I do not admit that I’ve not opened today’s letter, instead focusing on things that Stefan wrote last week. “They’ve apparently got a good deal of snow in Berlin, much more so than here.”

He nods. “Uncle Walter said the same. I’m sure you are eager to return to him. Stefan that is, not Uncle Walter.” I smile at this. My mother’s brother has never been a favorite of mine. “How is he?” Papa asks, an unmistakable note of fondness to his voice. Papa always liked Stefan—their gentle personalities were well suited to each other. Stefan did not share Papa’s razor-sharp intellect, but he always listened with rapt attention to Papa talk about the latest article he was writing.

“He’s working very hard at rehabilitation. He’s even managed to stand up a few times.”

“That’s remarkable. He wasn’t expected to live, so to get out of a chair is really something. Perhaps he’ll even get around with a walker someday. What an extraordinary young man.”

A pang of jealousy shoots through me. In some ways, Stefan is the son Papa never had. Not that Stefan could follow Papa into academia. The Osters were a once well-to-do banking family that had fallen on hard times. Stefan, as the oldest of four children and the only son, has been expected to somehow restore the family to a better station. We had hoped that he might join Uncle Walter and run one of the plants. But imagining him trying to navigate around the heavy machinery of the factory floor with a walker seems quite impossible now.

“He is doing really well,” I say, but something nags at me. “Do you think he is damaged, beyond his legs, I mean? His letters just feel a little off.” Papa wrinkles his brow, as if asking me to say more. But I can’t quite articulate my concern.

“It’s the war, darling. Give him time.” I nod. Stefan is such a good man. My heart breaks for the things he has seen and suffered. I cannot help but wonder, though, whether he will ever be whole again.

“Hopefully the conference will move quickly and we can return to Berlin soon so you can see him.”

I swallow over the lump that has formed in my throat. “Hopefully.”

“Good night, dear.” He walks to the desk and reaches for a stack of papers. Despite his slight size and quiet demeanor, Papa has always been the strongest man I’ve known. Not just strong: brave. Once when I was about six we’d been walking our German shepherd, Gunther, through the Tiergarten when a large stray confronted us, blocking the path ahead. My first instinct had been to leap back in fear. But Papa moved forward placing himself between gentle Gunther and the snarling beast. In that moment, I understood what it took to be a parent, in a way I might never quite be able to manage myself.

He has given up so much to raise me. After Mother died, it would have been logical for him to leave my upbringing to Tante Celia or governesses. But instead he had cut short his schedule at the university, declining to teach in the late afternoon and evening, and taking his work home so he could read alongside me. He had made me a part of his journeys and declined the opportunities where he could not because the destinations were too far-flung or the travel unsafe or good schools not available. There were times, I could tell, that conversation was too much and he was eager to escape into his work from the harshness of everyday life and the pain that he carried. He made sure, though, that I was never alone.

But now, hunched over the desk, he appears vulnerable. I am seized with the urge to reach down and hug him. Instead, I place a hand on his shoulder. He looks up, startled by my unexpected touch. We have never been very physically affectionate. “Good night, Papa.”

I return the dinner tray to the hall, then carry the lamp to my room so that Papa can work in the sitting room uninterrupted. I pull out the volume of Goethe I’d purchased from the bookseller and run my hand over the cover. Stefan would love it—or would have, once upon a time. We had always shared a deep passion for books and our families were frequently amused to find us sitting together under a tree in the garden or in the parlor, reading silently side by side, each lost in our own world. But is he even reading now? And would the book, with its references to death and suffering, just make things worse for him? I set it down on the table.

Stefan’s letter sits on the dresser. Reluctantly I open it.

Dearest Margot—

I can tell from the almost illegible script that he has tried to write himself this time instead of having the nurse do it.

I hope that this letter finds you well. Exciting news: Father is modifying the cottage and building an extension for us so we can live there after the wedding.

I cringe. Stefan is immobilized in a wheelchair—of course he cannot return to the Berlin town house with its many narrow stairs. I recall the Osters’ vacation cottage, a two-room house on the edge of a maudlin lake, more than an hour from the city. Are we really to live in the middle of nowhere? How will he earn a living?

I finger the ring that Stefan gave me before leaving for the front. I should have gone to be with him, a voice inside me nags for the hundredth time. I had good reasons for not going—first the war and later the railway lines and now Papa being summoned to Paris. There were ways I might have gone, though, if I pushed hard enough. But I hadn’t, instead embracing the excuses like a mantle, shielding myself from the truth that inevitably awaits. I slip the ring from my finger and put it in my pocket.

I fold the letter and put it back into the envelope without reading further.

A scrap of paper falls from the envelope and flutters to the floor. A photograph. I pick it up, wishing he had not sent it. He meant it as a good thing, sitting up in the wheelchair and smiling as if to say, Look how far I’ve come. In some ways it is better than the man I see in my nightmares, but his face is a stranger’s to me, the hollow eyes confirming everything I fear about our future together.

Perhaps being in Paris is not the worst thing, after all.

2

As we ascend the marble staircase to the ballroom at the Hôtel de Crillon, my impression is one of white—wreaths of lilies and roses climbing the columns, great swaths of snowy tulle draped from the balconies above. “I’ll just be a moment,” Papa says, heading in the direction of the cloakroom with our coats. I take the glass of wine that is offered to me by one of the servers, then step out of the flow of the crowd. The reception is like all of the other parties we have attended since coming to Paris, only magnified tenfold, the pond of gray-haired men in black tuxedos now a sea. A handful of women in expensive gowns, the deep maroon and dusky-rose shades that are the fashion this year, cling to the periphery. The savory smell of the hors d’oeuvres mixes with a cacophony of floral perfumes and cigarette smoke.

The orchestra at the front of the room breaks from the waltz it had been playing midstanza and bursts into a robust rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The guests hush, turning expectantly toward the entrance and there is a low murmur as President and Mrs. Wilson enter. The crowd parts to let them through. Closer now, he is taller than I thought, with a grimly set jaw.

A man I recognize from other occasions as the American ambassador, Stan Stahl, steps forward to greet the Wilsons. But before he can reach them, an Oriental boy, no older than myself, cuts in front of him and approaches the president. The boy, who wears not the uniform of a formal server but the white shirt and apron of the kitchen staff, holds an envelope outstretched in his shaking hand. An audible gasp runs through the ballroom.

One of the guards flanking Wilson moves to place himself between the president and the boy, but Wilson shakes him off. “He means no harm.” Wilson takes the letter and opens it. “Thank you,” he says, as solemnly as though he is speaking with one of the other Allied leaders. Apparently satisfied, the kitchen boy bows, then turns and disappears through one of the servers’ doors. Yelling can be heard from the other side.

What does the letter say, I wonder. The spectacle over, the crowd closes in to greet the Wilsons. I scan the room for Papa and find him in the corner, shanghaied by someone, undoubtedly a delegate wanting to secure his support for a resolution. Now that the conference is about to begin in earnest, those lobbying for certain issues have dropped all pretense of subtlety, haranguing Papa and others in positions of influence nonstop for their support. I don’t mind his being delayed—it is easier to be anonymous on my own, to slip back among the draperies and observe rather than participate. I only hope he will be able to extricate himself at some point. My curiosity at seeing Wilson satisfied, I am eager to escape back to the hotel, out of this starchy gown that Tante Celia selected for me and back to the novel I’d been reading.

The orchestra begins playing a waltz. Watching couples swirl around the floor, a memory flashes through my mind of a night not long after Stefan and I had started courting when he had come to the house to escort me to a school dance. He had arrived too early and as I brushed my hair I could hear him talking with Papa in the parlor below, their conversation somehow more awkward than usual. I came downstairs a few minutes later and Stefan’s eyes widened at the sight of me in my pink party dress. His hair was freshly trimmed and he wore a crisp white shirt I had not seen before.

“Here.” He held out a small corsage. As he helped me pin it on awkwardly, I smelled the aftershave he had surely borrowed from his father. We did not speak on the short ride to school. Everything was more formal, the way he held doors for me and helped me from the car, and I disliked the stiffness that interfered with our usual easy company. The school cafeteria had been decorated with crepe paper and vases of fresh wildflowers that could not quite mask the lingering smell of sauerkraut and wurst lunches that had worn its way into the cinder-block walls over the years.

As I see Stefan’s face in my mind, an unexpected flash of tenderness wells up inside me. He cared for me in a way that no one ever had except Papa—and I liked that. Before him, my world had always been solitary, with my mother gone and Papa ensconced in his work. Stefan’s near-constant presence made me feel somehow less alone. But I am longing for the boy I left four years ago. Even if I returned to Berlin this minute, things would be different.

My foot throbs, reminding me of the cracked dress shoe that I’ve neglected for months to replace. I duck into one of the side salons off the main ballroom, where a handful of people cluster around small tables with tiny white candles at the center, and sink into an empty chair by a potted fern. In the far corner, an older woman sits at a piano, head bowed, eyes closed as she plays.

When the pianist lifts her head I gasp slightly. She is the woman in blue who fled Wilson’s arrival, the one I’d followed from the square. That is why she looked familiar—I have seen her playing at a handful of the other gatherings since we arrived. I stand and start toward the piano. She is not beautiful, I decide instantly. The bridge of her nose is curved and her eyes set close, giving her a hawkish appearance. But her cheekbones are high and her hair upswept, making the harsh somehow regal.

I watch, fascinated. It is unusual to see a female musician, or a woman doing anything other than accompanying a man on his arm at these affairs. Of course, there are the cooks and maids and such, but the woman’s high-collared silk blouse and straight posture does not bespeak the serving class. She plays with her whole body, shoulders swaying side to side as her hands traverse the keys, partners in a dance.

She finishes playing and the last note resonates throughout the salon, but the guests are too engrossed in their conversations to notice or applaud. “That was lovely,” I remark. The woman glances up and I wait for her to thank me, or at least smile. But a flicker of something close to annoyance crosses her face. “Mahler, wasn’t it?” I say.

She blinks. “Yes, from his Sixth Symphony.” Her voice is low and husky, just short of masculine, and her French is accented slightly, hailing from somewhere eastern I cannot place.

“One of my favorites, though I haven’t heard it since before the war. I didn’t think they would have you play it here.” My words come out more bluntly that I’d intended.

“Music is not political.”

I want to tell her that everything is political now, from the wine that is served (always the chardonnay, never the Riesling) to the color of the tablecloths (a patriotic French blue). But I do not know her well enough to get into a debate.

“I play what I want,” the woman adds. She adjusts the thick chignon of hair, the chestnut color broken by a few strands of gray. “It’s not as if they pay me.”

“Oh?”

The woman shakes her head. “My parents won’t allow it. They think it would be unseemly to take money.” It sounds odd, a woman who must be close to forty listening to her parents. But I will always care about Papa’s approval.

She points through the doorway toward a cluster of silver-haired men in the main ballroom. “My father. He’s a diplomat.”

“Mine, as well.” I leap too eagerly at the commonality, ignoring the fact that Papa’s title is in fact only a formality, conferred to credential him to the conference.

“Mine is with the Polish delegation.” My excitement fades. The Germans and Poles had been on opposite sides of the war, enemies. We could not, in fact, have less in common. “I’m Polish, or will be if they ever get around to making us a country again,” she adds. I nod. Poland had been partitioned among Germany, Austria and Russia for the better part of a half century. “Hard to see how they’ll have the time with all of this socializing.” She gestures toward the larger gathering. “You’re German, aren’t you?”

I flush. I had worked so hard to remove any trace of an accent from both my French and English. But a musician with a trained ear, the woman can hear the slight flaws in my speech and discern their origin. “Yes.” I hold my breath, waiting some sign of disapproval.

Her expression remains neutral. “Or at least you are until they get around to making Germany no longer a country,” she says wryly.

I cringe at this. It is the great unanswered question of the peace conference, whispered about in the salons, debated openly in the bars and parties: What will happen to Germany? “Back home they believe that it will be a fair peace.”

“Yes, they have to, don’t they? I’m Krysia Smok,” she says, extending a hand.

“Margot Rosenthal. A pleasure.” I want to mention the fact that I have seen her before but that would beg the question of what she was doing in the park, too intrusive of someone I’ve just met.

“I didn’t think the German delegation was coming until late spring,” she remarks.

“They aren’t. That is, we aren’t part of the delegation. My father is a professor, he teaches at Oxford at the moment….” I can hear myself babbling now. “And he’s detailed to the conference, not the delegation.” I study her face, wondering if she is impressed by the distinction.

From behind the column comes tittering laughter. “Really, even the kitchen staff have political aims,” a woman comments in English. “Are we to have soufflé tonight or a political rally?”

“They say the Japanese will demand a statement of racial equality, too,” her companion replies in a hushed tone, as though saying it aloud might make it real.

“Americans,” Krysia scoffs as they walk away. “They think they’re so progressive. And yet women in the States still do not have the right to vote.” I consider her point. Women were only given the vote in Germany a year ago and I haven’t been back to have the chance.

Papa is at my side then. “Darling, I’m sorry to have left you. I was waylaid by a Dutchman.”

“It’s quite fine. Did you hear about the kitchen boy?”

“Yes, Indochinese, by the sound of things, and seeking Wilson’s support for some sort of autonomy.”

“Do you think he lost his job?”

“I think,” Papa replies gently, “that he did what he set out to do at the conference and …” He stops midsentence and turns to Krysia. “Forgive my manners.” Papa is not like some of the men at the conference, seeing through the staff as though they are not here. “I’m Margot’s father, Friedrich Rosenthal.”

“Papa, this is Krysia Smok.”

She tilts her head. “Rosenthal, the writer?”

He shifts, uncomfortable with the attention. “I’ve written a few academic books, yes.”

“I’m more acquainted with your articles.” How is Krysia, a pianist from Poland, familiar with my father? “I particularly enjoy your work on the interplay between the suffragist cause and socialism,” she adds, animated now.

Papa bows slightly. “I’m humbled. And I’d be delighted to discuss the subject with you further if you’d like to come around for tea tomorrow. For now, I must excuse myself. Margot, I’m afraid I need to stay to speak with one of the British representatives after this.” He pats my cheek. “The car will be out front for you. Don’t wait up for me. I shall see you in the morning.”

When he has gone, I turn back to Krysia. “How do you know my father’s work?”

“His writings on the advancement of women in the communist system have been very helpful to the suffragist cause.”

“Papa isn’t a communist,” I reply quickly, though I’ve never read Papa’s work myself.

She doesn’t hear me, or pretends not to. “I detest pure academics. But your father, well, he was quite active in the protests in his day.” Papa out of his study is an animal removed from natural habitat; it is difficult to fathom him on the streets, chanting angrily like the Serb nationalists in front of the foreign ministry on the Quai d’Orsay. There is much about him, I realize, that I do not know.

Her gaze travels the room and stops on the catering manager who has entered the salon and is staring at us. The reception is winding down and Krysia is meant to be playing as the guests leave, not talking. “It was a pleasure meeting you,” she says, shuffling through her sheet music.

“Come to tea tomorrow,” I press. I’m lonely for company beyond the superficial chatter of the parties and I’ve enjoyed these few brief moments of conversation more than any since our arrival.

She shakes her head, demurring. “Is it because we are German?”

“Of course not.” Her tone is sincere. “I have a prior obligation. Another time.”

“Here.” I reach into my pocket and pull out one of the calling cards that Tante Celia had insisted I need. They seemed so frivolous at the time, but I’m glad to have them now. “In case you change your mind.”

“Thank you.” Krysia puts the card in her pocket in a way that tells me she will never use it.

She resumes playing and I walk from the salon, deflated. In the main ballroom, the gathering has begun to dissipate. I make my way to the cloakroom and when I return, the piano bench is empty.

Outside, I scan the line of cars and find ours. There is a dampness to the frosty night air that I can almost taste. As I get in, I see Krysia walking from the hotel with her parents. She kisses them each on the cheek and starts in the other direction, her blue cape radiant in the sea of black. I watch as she slips away, quiet as a cat, then ducks into the alleyway before reaching the boulevard.

Where is she going alone at night? It is after ten and there is still a curfew. I climb from the car once more. “I’ll make my own way,” I say to the driver, shutting the door before he can protest.

I weave my way through the departing crowd, breaking free and turning down the alleyway where I last saw Krysia. The street is dark and I fear that I have lost her, but I hear footsteps ahead and quicken my pace. A moment later the passageway opens onto a wide avenue and Krysia appears in a yellow pool of streetlight. She moves swiftly, almost seeming to fly beneath the billowing cape. I struggle to stay back far enough so as not to be noticed.

Krysia reaches the corner and stops. Then she turns, facing me before I have time to hide. “You again!” I freeze, an animal trapped. “Are you following me?”

“No—” I protest too quickly.

“I was joking, of course. You’re staying in the area?”

“My hotel is nearby, but I am going to visit some friends.” I regret the lie as soon as I have spoken, the notion that I would be calling on anyone at this hour of the night hardly plausible.

She does not respond but continues walking, shrugging her shoulders in a way that suggests I am welcome to join her. We travel wordlessly along the rue Royale, the swish of her cape giving off a faint hint of lilac perfume.

“Did you come to Paris before the war?” I ask, hoping she will not mind conversation. My breath rises in tiny puffs of frost.

“Yes. There was not so much work for pianists in southern Poland.” She unfurls detail a bit at a time, like a kite string, or thread off a spool. “When the war broke out I found myself stranded here.” There is something deeper beneath the surface, a longing in her voice that belies a part of the story she is not willing to share with me. “But I miss home terribly. Do you?”

“I suppose.” I have not until just this moment thought about it. Our town house in Berlin’s Jewish quarter is not large—even as a child, I could touch both walls of my bedroom at the same time if I stretched my arms out sideways. But it is cozy and made beautiful by all of my mother’s decorations, the floral trim and slipcovers that Papa never would have thought to do himself and that he has left untouched since she died. There’s a tiny garden with a fountain in the back, a park down the road for strolling. It’s been years since we’ve actually lived there for any period of time, though. “We’ve been abroad for so long. Now home is wherever Papa and I land with a place to lay our heads and books to read.”

She smiles. “The vagabond lifestyle.” We reach the steps of the metro, a dark cavernous hole I’ve passed before but never entered. Krysia stops. “Your friends,” she says suddenly. For a moment I am confused. She is referring to my alibi for being out walking, the fact that we’ve long since left the neighborhood I purported to be visiting. “You really were following me.” It is not a question.

“I just …” I falter.

“What is it that you want from me?”

I try to come up with another excuse and then decide to be honest. “Company. I’m bored,” I say, my voice dangerously close to a whine.

Krysia arches an eyebrow. “Bored, in Paris?”

My statement must sound ludicrous. “Not with the city, exactly. It’s all of the parties and silly gossip.”

“So don’t go. Play your own game. No good can come from idleness. Come.”

The metro steps are damp and slick and I take care not to fall as I follow her down. Below, my senses are assaulted by the dank odor of garbage and waste. I avert my eyes from a pair of rats scurrying along the tracks, fighting the urge to yelp. The ground rumbles beneath our feet and a long wooden train rolls into the station, looking not unlike the trolley cars that travel the streets above. The car we board is empty but for an old man sleeping at the other end. It begins to move swiftly through the darkness. I try to act normal, as though accustomed to this strange mode of travel.

“I saw you at the arrival parade for Wilson,” I say, unable to hold back. Krysia stares vaguely over my shoulder and for a minute I doubt my memory, wondering if the woman at the parade had been someone else. “You left in the middle,” I press. The statement comes out abrupt and intrusive.

“I had somewhere to be.” She does not elaborate.

Two stops later the doors open and I follow Krysia back up onto the street, breathing in the fresh air deeply to clear the dankness from my lungs. We are on the Left Bank now, with its narrow, winding streets. This is Paris as I knew it as a girl, buildings leaning close, whispering secrets to one another. Parisians, still in the habit of conserving from the war, have shuttered and darkened their houses and only every other streetlight splutters in an attempt to save electricity. A low fog has rolled in from the river now, swirling eerily around us.

A few minutes later, we reach the boulevard du Montparnasse. The wide avenue is as bright as midday, light spilling forth from beneath the café awnings. A door to a café opens and a woman’s high tinkling laugh cascades over the music. La Closerie des Lilas reads the painted sign on the glass window of the café, smaller print advertising the billiards and rooms available on the floors above.

I follow Krysia inside, where she weaves through a maze of tables without waiting to be seated, steering toward the high mahogany bar with red leather stools. Shelves filled with bottles climb to the ceiling of the mirrored wall behind it. The room is warm and close, plumed with clouds of cigarette smoke. Ragtime music from an unseen gramophone plays lively in the background, mixing with boisterous conversation in French, German and a handful of other languages.

Behind the bar, a skinny brown-haired boy, eighteen or nineteen maybe, with coal-black eyes, stacks beer steins. Feeling his gaze follow me, I flush. I’m still not used to the kind of attention young women receive in Paris, so much more admiring and less veiled than in London or Berlin.

We reach an alcove behind the bar, not quite set off enough from the main part of the café to be its own room, a few tables with an odd assortment of chairs thrown haphazardly around them. A half-decorated Christmas tree lists in the corner.

Krysia pulls up two chairs to one of the tables, where a handful of men are gathered. I await the introductions that do not come, then sit down beside her. The marble table is littered with overflowing ashtrays and empty wine bottles and an untouched carafe of still water. Two candles in a brass dish burn at the center, melting together in a molten pool. The only woman, Krysia looks out of place in this group of rough men. But she chats easily, as if among family. The gathering crackles with conversation. Across from me two men are debating how the war will be remembered in the literature, while to my left there is a lively discussion about the future of Palestine. Ideas rise like champagne bubbles around me and I struggle to keep up, to grasp one before it is displaced by the next

“Is Marcin coming?” one of the men asks in accented French. His sideburns, wide and deep, lash onto his cheeks like daggers. He wears a red silk scarf around his neck, knotted jauntily.

Krysia shakes her head. “He’s playing a wedding at Chartres.”

The man snorts. “That’s a disgrace.”

“One has to eat,” Krysia replies vaguely, then turns to me. “Marcin is my husband.”

“Oh.” Krysia seems so solitary and stoic, an island unto herself. It is hard to imagine her needing or living with anyone.

“He plays cello.”

An older man, fiftyish and portly with a shock of white hair, pads over to the table and places fresh, foaming mugs of beer in front of us. “She’s too modest.” His vowels are rounded, as though his cheeks were full, a Russian accent unmuted by his time in France. “Marcin is one of the foremost cellists in Europe,” the man informs me. He begins twirling a coin between the knuckles of his left hand, index finger, middle, ring, pinky, and then back again without stopping. His fat fingers, each a sizable sausage, are surprisingly nimble. “He should be playing filled concert halls, not background music for wedding guests munching on canapés and cheap wine.”

The red-scarfed man beside me raises his glass. “Hear, hear.” His words are slurred.

Krysia pats the arm of the man who has handed us our drinks. “Margot, this principled fellow is Ignatz Stein.” I am surprised to hear her introduce the barman as a friend. “He owns this place.” I take a sip too large, caught off guard by the full, cold taste of hops, carrying me back to the fields of Bavaria in late harvest when Papa and I hiked there years earlier. The extra liquid spills out of the corner of my mouth. I reach for a napkin and, seeing none, furtively blot at the moisture with my sleeve, hoping no one will notice. Krysia turns to the man seated beside her. “And this is Deo Modigliani.”

“The artist?” I cannot help but blurt out, awestruck. I have studied his work, seen it in the finest galleries and museums. Yet here he is sitting in this nondescript café and drinking beer like everyone else. I’ve heard of this Paris, artists and writers gathering in the Montparnasse cafés to drink and share ideas. It exists beneath the surface, separate and secret from the pomp and formality of the conference and everyday life overhead.

Krysia does not answer but turns her attention to a debate on the future of Alsace-Lorraine that has heated up at the far end of the table. “Surely the territory will be returned to France now.” I have not been introduced to the man who is speaking.

“If the Americans and the French don’t tear one another apart first,” Krysia interjects. I nod. The conference is just days old and things had reportedly gotten quite contentious already.

“But the Americans …”

“It is quite easy to have views from halfway around the globe.” Her observation is unfair and yet at the same time true. The Americans came to help with the fighting and they are here to help make the peace. Yet they will return home, largely unscathed by what is decided here. So why are they at the center of it?

She continues, “If the conference is to be democratic, then why is so much being done by the Big Four behind closed doors? And where is Russia?” I watch in awe as Krysia speaks her mind in a forthright way, mixing logic and passion in the way of a woman long accustomed to debate. Holding court, she appears ethereal, bathed in light. I have seldom heard women offer up opinions and have never seen them received with such respect. There is a keen intensity to the way she speaks, her voice low and melodic and commanding, that makes her somehow beautiful.

“Did you hear a kitchen boy from the Orient sent Wilson a petition for his country’s freedom?” Modigliani offers, changing the subject.

“Ask Margot about it,” Krysia says, gesturing toward me with her head. “I was playing in one of the salons, but she saw the whole thing.”

“You were at the Wilson reception?” The barman, Ignatz, comes up to my chair, regarding me with newfound interest.

“Yes, my father is with the conference.”

“Her father is Friedrich Rosenthal,” Krysia adds with emphasis. Heads nod in recognition.

“Your father doesn’t write under a nom de plume,” Ignatz observes, still twirling a coin.

“No, why should he?”

“I think Ignatz only meant that not every writer has the courage to speak of such things in his own name,” Krysia clarifies. Courage. I recall the news from back home in Berlin, the violence that had erupted as a result of the civil unrest. Politicians has been shot for no more than their views. Could Papa and the other academics be in similar danger?

Modigliani leans in, his artist eyes soulful. “And what are you, ma petite?”

“Deo,” Krysia warns in a low voice, protective like an older sister.

I am uncertain how to answer. “I’m engaged,” I offer. My response is met with blank stares around the table.

“I believe,” Krysia prompts gently, “that he was asking what you are planning to do now that the war is over?” Krysia’s clarification is of little help. Before the war, my future was clear—marriage to Stefan, the biggest question being whether to live with Papa indefinitely or save for an apartment of our own. That world is gone now. But still the old ties and expectations remain.

“I don’t know,” I confess finally. The room is warm and wobbly from the beer.

“How exciting.” I search for sarcasm in her voice and find none. “Starting fresh, reborn out of the ashes. The war was horrible, but it has shaken things up, given each of us a chance to stake a claim for what she wants.”

“They say that Kolchak’s Whites are making gains at Perm …” Ignatz offers, turning the topic to Russia. I sit back, grateful to no longer be the focus. But I find the topic unsettling. Russia has become a wild land since the czar was taken down, his whole family murdered. The Bolsheviks are in charge, or at least most think so—the country has largely been cut off from the West and so only rumors trickle out.

“Papa says we need to engage with the Whites as well as the Bolsheviks,” I say, speaking up in spite of my own desire to remain inconspicuous. I fight to keep the uncertainty from my voice. But I sound childish, falling back on my father’s opinions as if I have none of my own. “That is, perhaps we can help them to form some sort of coalition government….” I falter, unaccustomed to the eyes on me. Even the dark-eyed boy behind the bar appears to be listening with interest. I have discussed politics with Papa all my life, but never in a public forum such as this.

“What else does Papa say?” Ignatz asks from where he stands behind Krysia, a note of chiding to his voice.

“That the conference will move quickly to act before Russia can subsume too much territory.” I speak quickly now, too far gone to stop. “With a quick vote on recognition of the new Croat-Serb state, for example. The vote is to take place as soon as the conference opens. And it seems that Wilson and Lloyd George are favorably predisposed to a Pan-Slavic nation. But Clemenceau is likely to side with Orlando and the Italians and hold it up….”

“They can vote all they want. Lenin will not compromise on any sort of coalition,” Krysia remarks. She is talking about the Bolshevik leader not with the same fear I’ve heard at the parties, but with a kind of hushed reverence.

“You’re communist?” I ask, recalling her description of Papa’s work.

“I detest labels,” she replies coolly. “I’d say socialist, really, though there’s nothing wrong with communism as an ideal.”

Thinking of the stories I’ve read about Russia, I shudder. “It’s anarchy. They destroy businesses and overthrow leaders. They murdered the czar’s whole family, even the children.”

“That’s the problem with Germans,” one of the men scoffs derisively. “No stomach for reform. As Lenin says, revolution will never come to Berlin because the Germans would want to queue up for it.”

“It’s a shame that social change has to be accomplished by such violent means,” Krysia says before I can respond to the insult. “Though the previous rulers were hardly saints. Really the ideas behind communism of equal contributions and distributions are good. But they’re being corrupted for power just like any other ideology.”

One of the men snorts. “Bah! The socialists are too weak to act on their principles. We can sit around here talking all night and it will do nothing. We need to do something.”

“Raoul …” Krysia says, and there is an undercurrent of warning to her voice. “We should go,” she adds abruptly.

I’ve offended her, I fret. But the gathering has begun to break up, and around us everyone is gathering their coats and reaching for their pockets for a few loose francs. I picture guiltily Papa’s allowance money folded neatly in my purse. Should I offer to pay? Only Modigliani sits motionless. “Am I to accept another drawing from you?” Ignatz asks him chidingly. I notice then that the wall behind the bar is covered with artwork, framed paintings and hastily pinned sketches to pay for food and drink. The artist does not answer, but stares into the distance, his eyes heavy lidded.

“You’ll see him home?” Krysia asks Ignatz, then turns to me without waiting for a response. “Spirits help the creative soul to a point,” she says in a low voice, as we make our way through the main room of the café. The crowd has ceded to the curfew, leaving beer bottles and overflowing ashtrays in their wake. “And then they destroy it.”

“Monsieur Modigliani, will he be all right?”

She nods. “Stein will kick him out at some point. Otherwise a good number of them would stay all night—these days, it’s cheaper than heating their flats.”

“So many artists. I’d heard of such things, but I had no idea….”

“They suffered during the war like everyone else with lack of food and money. But now they’re trying to recapture the lost time, the frenzy of life. And art is such a solitary business. Coming together like this gives them a sense of companionship. Though with all of the drinking and such, it’s a marvel they get any work done at all.”

Outside the night is icy. “What did that man, Raoul, I believe you called him, mean about ‘doing something’?”

She hesitates. “Nothing. They all like to talk big when they drink. What could a few artists do, anyway? It’s just that the way the peace conference is being conducted, it will still only be justice for some, a gift from the powerful if they choose to be beneficent. But true freedom is innate—given not by man but from God herself.” My jaw drops slightly at Krysia’s reference to God as a female.

Krysia hails a taxi and holds the door for me. I slide across the seat to make room for her. She does not get in, but starts to hand the driver some bills. “My flat is nearby,” she explains.

“I have money,” I say.

“Well, get home safely. And Deo is right. You should figure out what you want to do.”

“Do?”

“With your life. Self-determination isn’t just some abstract political notion, intended for the masses. Each of us must decide whom she will be, what we want for ourselves.” I had not thought about it in such a manner. “You’re not bored,” she observes. “You’re restless. Bored suggests a lack of interest in the world around you. But you drink in everything and can’t get enough. The world has come to Paris and you’re at the center of it all,” she adds. “The question now is what you do with it.”

I see myself then as undefined, a lump of clay. “But I’m just an observer.” In that moment, I grasp my own frustration—I am tired of just watching things play out in front of me like a performance on a stage. I want to take part.

“Why?” she demanded. “Why not allow yourself even for a minute to step outside the box into which you were born?”

“My father. And there are other reasons. My fiancé was wounded….” I falter, swept by the urge to tell Krysia how I feel about Stefan.

“We all have pasts.” Her tongue seems loosened by the alcohol and I think she might say something about her mysterious errand to the park. “There’s a new world being born,” she observes. “We each might as well make what we want of it.”

I look up at the dark slate of gray sky above, picturing the kitchen boy from the Orient, the one who was fighting for his country’s independence among the dirty dishes and food scraps. If he was not daunted in his quest, then how could I be? I hadn’t until this very moment seen the opportunity in all of the change, rules and norms discarded.

“Make Paris your own,” she exhorts again. “Do something, write something, take a class. You are young and unattached, at least for the moment.” I hold my breath, waiting for her to ask about my fiancé, but she continues. “You’re in one of the world’s greatest cities at the dawn of the modern age. You have resources, wits, talent. There’s no greater sin than to waste all of that. Find your destiny.” Before I can ask her how, she turns and disappears into the night.

3

I sit in the stillness of the study, the room dim but for the pale light that filters in, silhouetting the windowpane. Beyond the lattice of dark wood, the robin’s-egg-blue sky is laced with soft white clouds. A rolling wave of slate-gray domes and spires spills endlessly across the horizon, poking out from the haze that shrouds the city like a wreath. Bells chime unseen in the distance.

I wrap my hands around the too-hot cup of tea that sits before me on the table, then release it again and gaze down at the front page of yesterday’s Le Journal. The early mornings have always been mine. Papa loves to work long into the night, a lone lamp at the desk pooling yellow on the papers below. As a child, I often fell asleep to the sweet smell of pipe smoke, the sound of his pen scratching on the paper a familiar lullaby.

I eye the letter I’d started writing to Stefan the previous evening. I had written to him regularly when we were in En gland, of course. But I have not put pen to paper since our arrival in Paris simply because I did not know what to say about the fact that I had come here instead of going home.