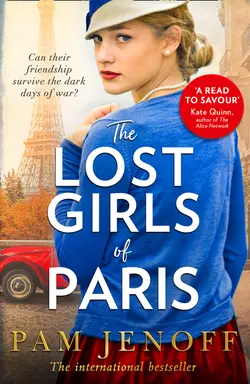

The Lost Girls Of Paris

Pam Jenoff

From the internationally bestselling author Pam Jenoff, The Lost Girls of Paris is an emotional and powerful journey through friendship and betrayal during the second world war, inspired by true events.1940s. With the world at war, Eleanor Trigg leads a mysterious ring of female secret agents in London. Twelve of these women are sent to aid the resistance.They never return home.1946. Passing through Grand Central Station, Grace Healey finds an abandoned suitcase tucked beneath a bench. The case is filled with a dozen photographs, each of a different woman.Setting out to find the women behind the pictures, Grace is drawn into the mystery of the lost girls of Paris. And as she delves deeper into the secrets of the past, she uncovers a story of fierce friendship, unthinkable bravery – and, ultimately, the worst kind of betrayal.

From the author of the runaway bestseller The Orphan’s Tale comes a remarkable story of friendship and courage centered around three women and a ring of female secret agents during World War II.

1946, Manhattan

One morning while passing through Grand Central Terminal on her way to work, Grace Healey finds an abandoned suitcase tucked beneath a bench. Unable to resist her own curiosity, Grace opens the suitcase, where she discovers a dozen photographs—each of a different woman. In a moment of impulse, Grace takes the photographs and quickly leaves the station.

Grace soon learns that the suitcase belonged to a woman named Eleanor Trigg, leader of a network of female secret agents who were deployed out of London during the war. Twelve of these women were sent to Occupied Europe as couriers and radio operators to aid the resistance, but they never returned home, their fates a mystery. Setting out to learn the truth behind the women in the photographs, Grace finds herself drawn to a young mother turned agent named Marie, whose daring mission overseas reveals a remarkable story of friendship, valor and betrayal.

Vividly rendered and inspired by true events, New York Times bestselling author Pam Jenoff shines a light on the incredible heroics of the brave women of the war and weaves a mesmerizing tale of courage, sisterhood and the great strength of women to survive in the hardest of circumstances.

PAM JENOFF is the author of several novels, including the phenomenal international bestseller The Orphan’s Tale, and Kommandant’s Girl, which was also an international bestseller and earned her a Quill Award nomination. Pam lives with her husband and three children near Philadelphia where, in addition to writing, she teaches law school.

Also by Pam Jenoff (#ud32e4584-82b1-54e6-9cbe-6d0b6a5f37b3)

Kommandant’s Girl

The Diplomat’s Wife

The Ambassador’s Daughter

The Winter Guest

The Last Embrace

The Orphan’s Tale

The Lost Girls of Paris

Pam Jenoff

Copyright (#ud32e4584-82b1-54e6-9cbe-6d0b6a5f37b3)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Pam Jenoff 2019

Pam Jenoff asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © January 2019 ISBN: 9781474083195

Praise for The Lost Girls of Paris (#ud32e4584-82b1-54e6-9cbe-6d0b6a5f37b3)

‘Based on true events, The Lost Girls of Paris brings us three courageous women who braved constant danger to survive.’

Martha Hall Kelly, author of Lilac Girls

‘Fraught with danger, filled with mystery, and meticulously researched, a fascinating tale of the hidden women who helped to win the war.’

Lisa Wingate, author of Before We Were Yours

‘Eleanor Trigg and her girls are every bit as human as they are brave. I couldn’t put this down.’

Jessica Shattuck, author of The Women in the Castle

‘Pam Jenoff’s meticulous research and gorgeous historical world-building lift her books to must-buy status.

An intriguing mystery and a captivating heroine make The Lost Girls of Paris a read to savour!’

Kate Quinn, author of The Alice Network

For my family

Contents

Cover (#ubc702a7c-7f91-52e1-ad09-8c4b6adf901c)

Back Cover Text (#uf2562c80-4702-5023-b1d1-daf1d832c67d)

About the Author (#u9e68a99b-e74a-5945-8847-7da90f0d3c23)

Booklist (#u0aec74bc-3558-59a9-a459-4180211dccf3)

Title Page (#uae2ab51b-ea51-5b42-8a3f-e58dc7a1d4af)

Copyright (#u0cf8752a-3277-5777-af8d-db5c15a22a08)

Praise (#uf388afcd-796c-587a-b1ac-4dddf1167284)

Dedication (#u88437c1d-08b9-5218-9756-993caa351643)

Quote (#ua00a26e8-f725-5418-b472-9924a7aab140)

Chapter One (#ufc8d26c5-59f5-506c-8e3c-68cb16724824)

Chapter Two (#ue818151f-6389-5f95-a8de-f29994a60017)

Chapter Three (#uf45c9482-b28f-5903-951b-117e02a4f583)

Chapter Four (#u4777d9c2-8f37-5360-89ff-0e4007459623)

Chapter Five (#uc1b9146d-5a31-5cf8-ba96-8244e0204ef5)

Chapter Six (#u5c494f0f-c8b4-5d82-a4d0-dadd9fddfcfb)

Chapter Seven (#ua897878d-42d5-5aac-8eec-367ae03bca52)

Chapter Eight (#u5d471e8a-63b0-5ee5-aaa1-7c0bf8eea906)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Questions for Discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

“In wartime, truth is so precious that she should alwaysbe attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

—Winston Churchill

Chapter One (#ud32e4584-82b1-54e6-9cbe-6d0b6a5f37b3)

Grace

New York, 1946

If not for the second-worst mistake of Grace Healey’s life, she never would have found the suitcase.

At nine twenty on a Tuesday morning, Grace should have been headed south on the first of two buses she took to get downtown, commuting from the rooming house in Hell’s Kitchen to the Lower East Side office where she worked. And she was on her way to work. But she was nowhere near the neighborhood she had come to call home. Instead, she was racing south on Madison Avenue, corralling her corkscrew hair into a low knot. She quickly removed her coat, despite the chill, so she could take off her mint green cardigan. She didn’t want Frankie to notice it was the exact same one she had been wearing at work the previous day and question the unthinkable: whether she had gone home at all.

Grace paused to study herself in the window of a five-and-dime. She wished the store was open so she could buy some powder to hide the marks on her neck and sample a bit of perfume to conceal the stench of day-old brandy mixed with that delicious-but-wrong smell of Mark’s aftershave, which made her dizzy and ashamed with every inhale. A wino sat on the corner, moaning to himself in sleep. Looking at his gray, lifeless pallor, Grace felt a certain solidarity. From the adjacent alley came the banging on a trash can, a sound marching in time with the thudding in her own head. The whole city of New York seemed green and hungover. Or perhaps she was confusing it for herself.

Sharp gusts of February wind cut across Madison, causing the flags that hung from the skyscrapers above to whip furiously. An old crumpled newspaper danced along the gutter. Hearing the bells of Saint Agnes’s toll half past nine, Grace pressed on, her skin growing moist under her collar as she neared a run. Grand Central Terminal loomed hulking ahead. Just a bit farther and she could turn left on Forty-Second Street and catch an express bus downtown on Lexington.

But as she neared the intersection at Forty-Third, the street ahead was blocked. Police cars sat three across, cordoning off Madison and preventing anyone from going farther south. A car accident, Grace suspected at first, noting the black Studebaker, which sat jackknifed across the street, steam billowing from the hood. More cars clogged the Midtown streets than ever these days, jockeying for space with the buses and taxis and trucks making deliveries. There did not appear to be another vehicle involved, though. A lone ambulance sat at the corner. The medics did not rush about urgently, but stood leaning against the vehicle, smoking.

Grace started toward a policeman, whose paunchy face pushed up from the high collar of his uniform, navy with gold buttons. “Excuse me. Will the street be closed for long? I’m late for work.”

He looked out at her disdainfully from under the brim of his hat, as if despite all of the women who had worked dutifully in the factories to take the place of the men who had enlisted and gone overseas during the war, the notion of a woman holding a job was still laughable. “You can’t go this way,” he replied officiously. “And you won’t be able to anytime soon.”

“What happened?” she asked, but the policeman turned away. Grace took a step forward, craning to see.

“A woman was hit by a car and died,” a man in a flat wool cap beside her said.

Taking in the shattered windshield of the Studebaker, Grace suddenly felt sick. “Such a shame,” she managed finally.

“I didn’t see it,” the man replied. “But someone said she was killed instantly. At least she didn’t suffer.”

At least. That was the phrase Grace heard too often after Tom had died. At least she was still young. At least there had not been children—as if that made it somehow easier to bear. (Children, she sometimes thought, would not have been a burden, but a bit of him left behind forever.)

“You just never know where it will all end,” mused the flat-capped man beside her. Grace did not answer. Tom’s death had been unexpected, too, an overturned jeep on the way from the army base to the train station in Georgia, headed to New York to see her before he’d deployed. They called him a casualty of war, but in fact it had been just another accident that might have happened anywhere.

A flashbulb from a reporter’s camera popped, causing her to blink. Grace shielded her eyes then backed away blindly through the crowd that had formed, seeking air amid the cigarette smoke and sweat and perfume.

Away from the police barricade now, Grace looked over her shoulder. Forty-Third Street was blocked to the west as well, preventing her from cutting across. To go back up Madison and around the other side of the station would take at least another half an hour, making her even later for work than she already was. Again, she cursed the night before. If it weren’t for Mark, she wouldn’t be standing here, faced with no other choice than to cut through Grand Central—the one place she had sworn to never go again.

Grace turned to face it. Grand Central loomed before her, its massive shadow darkening the pavement below. Commuters streamed endlessly through its doors. She imagined the inside of the station, the concourse where the light slatted in through the stained glass windows, the big clock where friends and lovers met. It was not the place she couldn’t bear to see, but the people. The girls with their fresh red lipstick, pressing tongues against teeth to make sure the color hadn’t bled through, clutching purses expectantly. Freshly washed children looking just a bit nervous at seeing a father who they could not remember because he had left when they were scarcely toddlers. The soldiers in uniforms rumpled from travel bounding onto the platform with wilted daisies in hand. The reunion that would never be hers.

She should just give up and go home. Grace longed for a nice bath, perhaps a nap. But she had to get to work. Frankie had interviews with a French family at ten and needed her to take dictation. And after that the Rosenbergs were coming, seeking papers for housing. Normally this was what she loved about the work, losing herself in other peoples’ problems. But today the responsibility weighed down heavy upon her.

No, she had to go forward and there was only one choice. Squaring her shoulders, Grace started toward Grand Central.

She walked through the station door. It was the first time she had been here since that afternoon she’d arrived from Connecticut in her best shirred dress, hair perfectly coiffed in victory rolls and topped with her pillbox hat. Tom hadn’t arrived on the three from Philadelphia, where he should have changed trains, as expected and she assumed he had missed his connection. When he didn’t get off the next train either, she became a bit uneasy. She checked the message board beside the information booth at the center of the station, where people pinned notes in case Tom had come early or she had somehow missed him. She had no way to reach him or check and there was nothing to do but wait. She ate a hot dog that smudged her lipstick and turned sour in her mouth, read the newspaper headlines at the kiosk a second, then a third time. Trains came and emptied, spilling onto the platform soldiers who might have been Tom but weren’t. By the time the last train of the night arrived at eight thirty, she was frantic with worry. Tom never would have left her standing like this. What had happened? Finally, an auburn-haired lieutenant she’d recognized from Tom’s induction ceremony came toward her with an expression of dread and she’d known. She could still feel his unfamiliar hands catching her as her knees buckled.

The station looked the same now as it had that night, a businesslike, never-ending stream of commuters and travelers, undisturbed by the role it had played so large in her mind these many months. Just get across, she told herself, the wide exit at the far side of the station calling to her like a beacon. She didn’t have to stop and remember.

Something pulled at her leg strangely, like the tearing of a small child’s fingers. Grace stopped and looked behind her. It was only a run in her nylons. Had Mark’s hands made it? The tear was growing larger with every step now, an almost gash across her calf. She was seized with the need to get them off.

Grace raced for the stairs to the public washroom on the lower level. As she passed a bench, she stumbled, nearly falling. Her foot twisted, causing a wave of pain to shoot through her ankle. She limped to the bench and lifted her foot, assuming that the heel that she had not had fixed properly had come off again. But the shoe was still intact. No, there was something jutting out from beneath the bench she had just passed that had caused her to trip. A brown suitcase, shoved haphazardly beneath. She looked around with annoyance, wondering who could have been so irresponsible as to leave it like that, but there was no one close and the other people passed by without taking notice. Perhaps whoever owned it had gone to the restroom or to buy a newspaper. She pushed it farther underneath the bench so that no one else would trip on it and kept walking.

Outside the door to the ladies’ room, Grace noticed a man sitting on the ground in a tattered uniform. For a fleeting second, she was glad Tom had not lived to fight and return destroyed from what he had seen. She would always have the golden image of him, perfect and strong. He would not come home scarred like so many she saw now, struggling to put a brave face over the brokenness. Grace reached in her pocket for the last of her coins, trying not to think about the coffee she so dearly wanted that she would now have to do without. She pressed the money into the man’s cracked palm. She simply couldn’t look away.

Grace continued into the ladies’ room, locking herself in a stall to remove her nylons. Then she walked to the mirror to smooth her ink-black hair and reapply her Coty lipstick, tasting in its waxiness all that had happened the night before. At the next sink, a woman younger than herself smoothed her coat over her rounded belly. Pregnancies were everywhere now, it seemed, the fruits of so many joyous reunions with the boys who came home from the war. Grace could feel the woman looking at her disheveled appearance. Knowing.

Mindful that she was even later now for work, Grace hurried from the restroom. As she started across the station once more, she noticed the suitcase she had nearly tripped over moments earlier. It was still sitting under the bench. Slowing, she walked to the suitcase, looking around for someone coming to claim it.

When no one did, Grace knelt to examine the suitcase. There was nothing terribly extraordinary about it, rounded like a thousand other valises that travelers carried through the station every day, with a worn mother-of-pearl handle that was nicer than most. Only this one wasn’t passing through; it was sitting under a bench unattended. Abandoned. Had someone lost it? She stopped with a moment’s caution, remembering a story from during the war about a bag that was actually a bomb. But that was all over, the danger of invasion or other attack that had once seemed to lurk around every corner now faded.

Grace studied the case for some sign of ownership. There was a name chalked onto the side. She recalled uneasily some of Frankie’s clients, survivors whom the Germans had forced to write their names on their suitcases in a false promise that they would be reunited with their belongings. This one bore a single word: Trigg.

Grace considered her options: tell a porter, or simply walk away. She was late for work. But curiosity nagged at her. Perhaps there was a tag inside. She toyed with the clasp. It popped open in her fingers seemingly of its own accord. She found herself lifting the lid a few inches. She glanced over her shoulder, feeling as though at any minute she might get caught. Then she looked inside the suitcase. It was neatly packed, with a silver-backed hairbrush and an unwrapped bar of Yardley’s lavender soap tucked in a top corner, women’s clothes folded with perfect creases. There was a pair of baby shoes tucked in the rear of the case, but no other sign of children’s clothing.

Suddenly, being in the suitcase felt like an unforgivable invasion of privacy (which, of course, it was). Grace pulled back her hand quickly. As she did, something sliced into her index finger. “Ouch!” she cried aloud, in spite of herself. A line of blood an inch or more long, already widening with red bubbles, appeared. She put her finger to her mouth, sucking on the wound to stop the bleeding. Then she reached for the case with her good hand, needing to know what had cut her, a razor or knife. Below the clothes was an envelope, maybe a quarter inch thick. The sharp edge of the paper had cut her hand. Leave it, a voice inside her seemed to say. But unable to stop herself, she opened the envelope.

Inside lay a pack of photographs, wrapped carefully in a piece of lace. Grace pulled them out, and as she did a drop of blood seeped from her finger onto the lace, irreparably staining it. There were about a dozen photos in all, each a portrait of a single young woman. They looked too different to be related to one another. Some wore military uniforms, others crisply pressed blouses or blazers. Not one among them could have been older than twenty-five.

Holding the photos of these strangers felt too intimate, wrong. Grace wanted to put them away, forget what she had seen. But the eyes of the girl in the top photo were dark and beckoning. Who was she?

Just then there were sirens outside the station and it felt as though they might be meant for her, the police coming to arrest her for opening someone else’s bag. Hurriedly, Grace struggled to rewrap the photos in the lace and put the whole thing back into the suitcase. But the lace bunched and she could not get the packet back into the envelope. The sirens were getting louder now. There was no time. Furtively, she tucked the photos into her own satchel and she pushed the suitcase back under the bench with her foot, well out of sight.

Then she started for the exit, the wound on her finger throbbing. “I should have known,” she muttered to herself, “that no good could ever come from going into the station.”

Chapter Two (#ud32e4584-82b1-54e6-9cbe-6d0b6a5f37b3)

Eleanor

London, 1943

The Director was furious.

He slammed his paw-like hand down on the long conference table so hard the teacups rattled and tea sloshed over the rims all the way at the far end. The normal banter and chatter of the morning meeting went silent. His face reddened.

“Another two agents captured,” he bellowed, not bothering to lower his voice. One of the typists passing in the corridor stopped, taking in the scene with wide eyes before scurrying on. Eleanor stood hurriedly to close the door, swatting at the cloud of cigarette smoke that had formed above them.

“Yes, sir,” Captain Michaels, the Royal Air Force attaché, stammered. “The agents dropped near Marseille were arrested, just hours after arrival. There’s been no word and we’re presuming they’ve been killed.”

“Which ones?” the Director demanded. Gregory Winslow, Director of Special Operations Executive, was a former army colonel, highly decorated in the Great War. Though close to sixty, he remained an imposing figure, known only as “the Director” to everyone at headquarters.

Captain Michaels looked flummoxed by the question. To the men who ran the operation from afar, the agents in the field were nameless chess pieces.

But not to Eleanor, who was seated beside him. “James, Harry. Canadian by birth and a graduate of Magdalen College, Oxford. Peterson, Ewan, former Royal Air Force.” She knew the details of every man they’d dropped into the field by heart.

“That makes the second set of arrests this month.” The Director chewed on the end of his pipe without bothering to light it.

“The third,” Eleanor corrected softly, not wanting to enrage him further but unwilling to lie. It had been almost three years since Churchill had authorized the creation of Special Operations Executive, or SOE, and charged it with the order to “set Europe ablaze” through sabotage and subversion. Since then, they had deployed close to three hundred agents into Europe to disrupt munitions factories and rail lines. The majority had gone into France as part of the unit called “F Section” to weaken the infrastructure and arm the French partisans ahead of the long-rumored cross-Channel Allied invasion.

But beyond the walls of its Baker Street headquarters, SOE was hardly regarded as a shining success. MI6 and some of the other traditional government agencies resented SOE’s sabotage, which they saw as amateurish and damaging to their own, more clandestine, operations. The success of SOE efforts were also hard to quantify, either because they were classified or because their effect would not be fully felt until the invasion. And lately things had started to go wrong, their agents arrested in increasing number. Was it the size of the operations that was the problem, making them victims of their own success? Or was it something else entirely?

The Director turned to Eleanor, newfound prey that had suddenly caught the lion’s attention. “What the hell is happening, Trigg? Are they ill prepared? Making mistakes?”

Eleanor was surprised. She had come to SOE as a secretary shortly after the organization was created. Getting hired had been an uphill battle: she was not just a woman, but a Polish national—and a Jew. Few thought she belonged here. Oftentimes she wondered herself how she’d come from her small village near Pinsk to the halls of power in London. But she’d persuaded the Director to give her a chance, and through her skill and knowledge, meticulous attention to detail and encyclopedic memory, she had gained his trust. Even though her title and pay had remained the same, she was now much more of an advisor. The Director insisted that she sit not with the other secretaries along the periphery, but at the conference table immediately to his right. (He did this in part, she suspected, to compensate for his deafness in his ear on that side, which he admitted to no one else. She always debriefed him in private just after the meeting to make certain he had not missed anything.)

This was the first time, though, that the Director had asked for her opinion in front of the others. “Respectfully, sir, it isn’t the training, or the execution.” Eleanor was suddenly aware of every eye on her. She prided herself on lying low in the agency, drawing as little attention as possible. But now her cover, so to speak, had been blown, and the men were watching her with an unmasked skepticism.

“Then what is it?” the Director asked, his usual lack of patience worn even thinner.

“It’s that they are men.” Eleanor chose her words carefully, not letting him rush her, wanting to make him understand in a way that would not cause offense. “Most of the young Frenchmen are gone from the cities or towns. Conscripted to the LVF, off fighting for the Vichy collaborationist militia or imprisoned for refusing to do so. It’s impossible for our agents to fit in now.”

“So what then? Should we send them all to ground?”

Eleanor shook her head. The agents could not go into hiding. They needed to be able to interact with the locals in order to get information. It was the waitress in Lautrec overhearing the officers chatter after too much wine, the farmer’s wife noticing changes in the trains that passed by the fields, the observations of everyday citizens that yielded the real information. And the agents needed to be making contacts with the reseau, the local networks of resistance, in order to fortify their efforts to subvert the Germans. No, the agents of the F Section could not operate by hiding in the cellars and caves.

“Then what?” the Director pressed.

“There’s another option...” She faltered and he looked at her impatiently. Eleanor was not one to be at a loss for words, but what she was about to say was so audacious she hardly dared. She took a deep breath. “Send women.”

“Women? I don’t understand.”

The idea had come to her weeks earlier as she watched one of the girls in the radio room decode a message that had come through from a field agent in France with a swift and sure hand. Her talents were wasted, Eleanor thought. The girl should be transmitting from the field. The idea had been so foreign that it had taken time to crystalize in Eleanor’s own mind. She had not meant to bring it up now, or maybe ever, but it had come out nonetheless, a half-formed thing.

“Yes.” Eleanor had heard stories of women agents, rogue operatives working on their own in the east, carrying messages and helping POWs to escape. Such things had happened in the First World War as well, probably to a greater extent than most people imagined. But to create a formal program to actually train and deploy women was something altogether different.

“But what would they do?” the Director asked.

“The same work as the men,” Eleanor replied, suddenly annoyed at having to explain what should have been obvious. “Courier messages. Transmit by radio. Arm the partisans, blow up bridges.” Women had risen up to take on all sorts of roles on the home front, not just nursing and local guard. They manned antiaircraft guns and flew planes. Why was the notion that they could do this, too, so hard to understand?

“A women’s sector?” Michaels interjected, barely containing his skepticism.

Ignoring him, Eleanor turned to face the Director squarely. “Think about it, sir,” she said, gaining steam as the idea firmed in her mind. “Young men are scarce in France, but women are everywhere. They blend in on the street and in the shops and cafés.”

“As for the other women who work here already...” She hesitated, considering the wireless radio operators who labored tirelessly for SOE. On some level they were perfect: skilled, knowledgeable, wholly committed to the cause. But the same assets that made them ideal also rendered them useless for the field. They were simply too entrenched to train as operatives, and they had seen and knew too much to be deployed. “They won’t do either. The women would need to be freshly recruited.”

“But where would we find them?” the Director asked, seeming to warm to the idea.

“The same places we do the men.” It was true they didn’t have the corps of officers from which to recruit. “From the WACs or the FANYs, the universities and trade schools, or in the factories or on the street.” There was not a single résumé that made an ideal agent, no special degree. It was more of a sense that one could do the work. “The same types of people—smart, adaptable, proficient in French,” she added.

“They would have to be trained,” Michaels pointed out, making it sound like an insurmountable obstacle.

“Just like the men,” Eleanor countered. “No one is born knowing how to do this.”

“And then?” the Director asked.

“And then we deploy them.”

“Sir,” Michaels interjected. “The Geneva Convention expressly prohibits women combatants.” The men around the table nodded their heads, seeming to seize on the point.

“The convention prohibits a lot of things,” Eleanor shot back. She knew all of the dark corners of SOE, the ways in which the agency and others cut corners and skirted the law in the desperation of war. “We can make them part of the FANY as a cover.”

“We’d be risking the lives of wives, daughters and mothers,” Michaels pointed out.

“I don’t like it,” said one of the other uniformed men from the far end of the table. Nervousness tugged at Eleanor’s stomach. The Director was not the most strong-willed of leaders. If the others all lined up behind Michaels, he might back away from the idea.

“Do you like losing a half-dozen men every fortnight to the Germans?” Eleanor shot back, scarcely believing her own nerve.

“We’ll try it,” the Director said with unusual decisiveness, foreclosing any further debate. He turned to Eleanor. “Set up an office down the street at Norgeby House and let me know what you need.”

“Me?” she asked, surprised.

“You thought of it, Trigg. And you’re going to run the bloody thing.” Recalling the casualties they had discussed just minutes earlier, Eleanor cringed at the Director’s choice of words.

“Sir,” Michaels interjected. “I hardly think that Miss Trigg is qualified. Meaning no offense,” he added, tilting his head in her direction. The men looked at her dubiously.

“None taken.” Eleanor had long ago hardened herself to the dismissiveness of the men around her.

“Sir,” the army officer at the far end of the table interjected. “I, too, find Miss Trigg a most unlikely choice. With her background...” Heads nodded around the table, their skeptical looks accompanied by a few murmurs. Eleanor could feel them studying her, wondering about her loyalties. Not one of us, the men’s expressions seemed to say, and not to be trusted. For all that she did for SOE, they still regarded her as an enemy. Alien, foreign. It was not for lack of trying. She had worked to fit in, to mute all traces of her accent. And she had applied for British citizenship. Her naturalization application had been denied once, on grounds that even the Director, for all of his power and clearances, had not been able to ascertain. She had resubmitted it a second time a few months earlier with a note of recommendation from him, hoping this might make the difference. Thus far, she had not received a response.

Eleanor cleared her throat, prepared to withdraw from consideration. But the Director spoke first. “Eleanor, set up your office,” he ordered. “Begin recruiting and training the girls with all due haste.” He raised his hand, foreclosing further discussion.

“Yes, sir.” She kept her head up, unwilling to look away from the eyes now trained upon her.

After the meeting, Eleanor waited until the others had left before approaching the Director. “Sir, I hardly think...”

“Nonsense, Trigg. We all know you are the man for the job, if you’ll pardon the expression. Even the military chaps, though they may not want to admit it or quite understand why.”

“But, sir, even if that is true, I’m an outsider. I don’t have the clout.”

“You’re an outsider, and that is just one of the things that makes you perfect for the position.” He lowered his voice. “I’m tired of it all getting mired by politics. You won’t let personal loyalties or other concerns affect your judgment.” She nodded, knowing that was true. She had no husband or children, no outside distractions. The mission was the only thing that mattered—and always had been.

“Are you sure I can’t go?” she asked, already knowing the answer. Though flattered that he wanted her to run the women’s operation, it would still be a distant second-best to actually deploying as one of the agents in the field.

“Without the paperwork, you couldn’t possibly.” He was right, of course. In London, she might be able to hide her background. But to get papers to send her over, especially now, while her citizenship application was pending, was another matter entirely. “Anyway, this is much more important. You’re the head of a department now. We need you to recruit the girls. Train them. It has to be someone they trust.”

“Me?” Eleanor knew the other women who worked at SOE saw her as cold and distant, not the type they would invite to lunch or tea, much less confide in.

“Eleanor,” the Director continued, his voice low and stern, eyes piercing. “Few of us are finding ourselves where we expected at the start of the war.”

That, she reflected, was more true than he possibly could have known. She thought about what he was asking. A chance to take the helm, to try to fix all of the mistakes that she’d been forced to watch from the sidelines these many months, powerless to do anything. Though one step short of actual deployment, this would be an opportunity to do so much more.

“We need you to figure out where the girls belong and get them there,” the Director continued on, as though it had all been settled and she’d said yes. Inwardly, Eleanor felt conflicted. The prospect of taking this on was appealing. At the same time, she saw the enormity of the task splayed before her on the table like a deck of cards. The men already faced so much, and while in her heart she knew that the women were the answer, getting them ready would be Herculean. It was too much, the kind of involvement—and exposure—that she could hardly afford.

Then she looked up at the photos on the wall of fallen SOE agents, young men who had given everything for the war. She imagined the German security intelligence, the Sicherheitsdienst, at their French headquarters on the Avenue Foch in Paris. The SD was headed by the infamous Sturmbannführer Hans Kriegler, a former concentration camp commandant who Eleanor knew from the files to be as cunning as he was cruel. There were reports of his using the children of locals to coerce confessions, of hanging prisoners alive from meat hooks to withdraw information before leaving them there to die. He was undoubtedly planning the downfall of more agents even as they spoke.

Eleanor knew then that she had no choice but to take on the task. “Fine. I’ll need complete control,” she added. It was always important to go first when setting the terms.

“You shall have it.”

“And I report only to you.” Special sectors would, in other circumstances, report through one of the Director’s deputies. Eleanor peered out of the corner of her eye at Michaels, who lingered in the hallway. He and the other men would not be happy about her having the Director’s ear, even more so than she already had. “To you,” she repeated for emphasis, letting her words sink in.

“No bureaucratic meddling,” the Director promised. “You report only to me.” She could hear then the desperation in his voice, how very much he needed her to make this work.

Chapter Three (#ud32e4584-82b1-54e6-9cbe-6d0b6a5f37b3)

Marie

London, 1944

The last place Marie would have expected to be recruited as a secret agent (if indeed she could have anticipated it at all) was in the loo.

An hour earlier, Marie sat at a table by the window in the Town House, a quiet café on York Street she had come to frequent, savoring a few minutes of quiet after a day of endless clacking at the dingy War Office annex where she had taken a position as a typist. She thought of the coming weekend, just two days off, and smiled, imagining five-year-old Tess and the crooked tooth that surely would have come in a bit more by now. That was the thing about only seeing her daughter on the weekend—Marie seemed to miss years in the days in between. She wanted to be out in the country with Tess, playing by the brook and digging for stones. But someone had to stay here and make a few pounds in order to keep their aging row home in Maida Vale from falling into foreclosure or disrepair, assuming the bombs didn’t take it all first.

There was a booming noise in the distance, causing the dishes on the table to rattle. Marie started, reaching instinctively for the gas mask that no one carried anymore since the Blitz had ended. She lifted her gaze to the plate glass window of the café. Outside the rain-soaked street, a boy of no more than eight or nine was trying to scrape up bits of coal from the pavement. Her stomach ached. Where was his mother?

She remembered the day more than two years ago that she’d decided to send Tess away. At first, the notion of being separated from her daughter was almost unthinkable. Then a bomb had hit the flats across the street, killing seven children. But for the grace of God, that might have been Tess. The next morning, Marie began making arrangements.

At least Tess was with Aunt Hazel. The woman was more of a cousin and a bit dour to be sure, but was nevertheless fond of the little girl. And Tess loved the old vicarage in East Anglia, with its endless cupboards and musty crawl spaces. She could run wild across the fens when the weather permitted, and help Hazel with her work at the post office when it did not. Marie couldn’t imagine putting her girl on a train to be sent off to the countryside to a cold convent or God-knows-where-else, into the arms of strangers. She had seen it at King’s Cross almost every Friday last year as she made her way north to visit Tess—mothers battling back tears as they adjusted coats and scarves on the little ones, younger siblings clinging to older, children with too-large suitcases crying openly, trying to escape through the carriage windows. It made the two-hour journey until she could reach Tess and wrap her arms around her almost unbearable. She stayed each Sunday until Hazel reminded her that she had best take the last train or miss curfew. Her daughter was safe and well and with family. But that didn’t make the fact that it was only Wednesday any more bearable.

Should she have brought Tess back already? That was the question that had dogged Marie these past few months as she had seen the trickle of children coming back to the city. The Blitz was long over and there was a kind of normalcy that had resumed now that they weren’t sleeping in the Tube stations at night. But the war was far from won, and Marie sensed that something far worse was yet to come.

Pushing her doubts aside, Marie pulled a book from her bag. It was poetry by Baudelaire, which she loved because his elegant verse took her back to happier times as a child summering on the coast in Brittany with her mother.

“Excuse me,” a man said a moment later. She looked up, annoyed by the interruption. He was fortyish, thin and unremarkable in a tweedy sport coat and glasses. A scone sat untouched on the plate at the table next to her from which he had risen. “I was curious about what you are reading.” She wondered if he were trying to make advances. The intrusions were everywhere now with all of the American GIs in the city, spilling from the pubs at midday and walking three abreast in the streets, their jarring laughter breaking the stillness.

But the man’s accent was British and his mild expression contained no hint of impropriety. Marie held up the book so that he could see. “Would you mind reading me a bit?” he asked. “I’m afraid I don’t speak French.”

“Really, I don’t think...” she began to demur, surprised by the odd request.

“Please,” he said, cutting her off, his tone almost imploring. “You’d be doing me a kindness.” She wondered why it meant so much to him. Perhaps he had lost someone French or was a veteran who had fought over there.

“All right,” she relented. A few lines couldn’t hurt. She began to read from the poem, “N’importe où hors du monde (Anywhere Out of the World).” Her voice was self-conscious at first, but she felt herself slowly gain confidence.

After a few sentences, Marie stopped. “How was that?” She expected him to ask her to read further.

He did not. “You’ve studied French?”

She shook her head. “No, but I speak it. My mother was French and we spent summers there when I was a child.” In truth, the summers had been an escape from her father, an angry drunk unable to find work or hold down a job, resentful of her mother’s breeding and family money and disappointed that Marie wasn’t a boy. That was the reason Marie and her mother summered far away in France. And it was the reason Marie had run away from the Herefordshire manor where she’d been raised to London when she was eighteen, and then took her mother’s surname. She knew if she stayed in the house she had dreaded all her childhood with her father’s worsening temper, she wouldn’t make it out alive.

“Your accent is extraordinary,” the man said. “Nearly perfect.” How could he know that if he didn’t speak French? she wondered. “Are you working?” he asked.

“Yes,” she blurted. The transition in subject was abrupt, the question too personal. She stood hurriedly, fumbling in her purse for coins. “I’m sorry, but I really must go.”

The man reached up and when she looked back she saw he was holding a business card. “I didn’t mean to be rude. But I was wondering if you would like a job.” She took the card. Number 64 Baker Street, was all it said. No person or office named. “Ask for Eleanor Trigg.”

“Why should I?” she asked, perplexed. “I have a job.”

He shook his head slightly. “This is different. It’s important work and you’d be well suited—and well compensated. I’m afraid I can’t say any more.”

“When should I go there?” she asked, though certain that she never would.

“Now.” She’d expected an appointment. “So you’ll go?”

Marie left a few coins on the table and left the café without answering, eager to be away from the man and his intrusiveness. Outside, she opened her umbrella and adjusted her burgundy print scarf to protect against the chill. She rounded the corner, then stopped, peering over her shoulder to make sure he had not followed her. She looked down at the card, simple black and white. Official.

She could have told the man no, Marie realized. Even now, she could throw out the card and walk away. But she was curious; what kind of work, and for whom? Perhaps it was something more interesting than endless typing. The man had said it paid well, too, something she dearly needed.

Ten minutes later, Marie found herself standing at the end of Baker Street. She paused by a red post box at the corner. The storied home of Sherlock Holmes was meant to be on Baker Street, she recalled. She had always imagined it as mysterious, shrouded in fog. But the block was like any other, drab office buildings with ground floor shops. Farther down the row there were brick town houses that had been converted for business use. She walked to Number 64, then hesitated. Inter-Services Research Bureau, the sign by the door read. What on earth was this all about?

Before she could knock the door flew open and a hand that did not seem attached to anybody pointed left. “Orchard Court, Portman Square. Around the corner and down the street.”

“Excuse me,” Marie said, holding up the card though there seemed to be no one to see it. “My name is Marie Roux. I was told to come here and ask for Eleanor Trigg.” The door closed.

“Curiouser and curiouser,” she muttered, thinking of Tess’s favorite book, the illustrated version of Alice in Wonderland Marie read aloud to her when she visited. Around the corner there were more row houses. She continued down the street to Portman Square and found the building marked “Orchard Court.” Marie knocked. There was no answer. The whole thing was starting to feel like a very odd prank. She turned, ready to go home and forget this folly.

Behind her, the door opened with a creak. She spun back to face a white-haired butler. “Yes?” He stared at her coldly, like she was a door-to-door salesman peddling something unwanted. Too nervous to speak, she held out the card.

He waved her inside. “Come.” His tone was impatient now, as though she was expected and late. He led her through a foyer, its high ceiling and chandelier giving the impression that it had once been the entranceway to a grand home. He opened a door on his right, then closed it again quickly. “Wait here,” he instructed.

Marie stood awkwardly in the foyer, feeling entirely as though she did not belong. She heard footsteps on the floor above and turned to see a handsome young man with a shock of blond hair descending a curved staircase. Noticing her, he stopped. “So, you’re part of the Racket?” he asked.

“I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

He smiled. “Just wandered in then?” He did not wait for an answer. “The Racket—that’s what we call all of this.” He gestured around the foyer.

The butler reappeared, clearing his throat. His stern expression gave Marie the undeniable sense that they were not supposed to be speaking with one another. Without another word, the blond man disappeared around the corner into another of what seemed to be an endless number of doors.

The butler led her down the hallway and opened the door to an onyx-and-white-tiled bathroom. She turned back, puzzled; she hadn’t asked for the loo. “Wait in here.”

Before Marie could protest, the butler closed the door, leaving her alone. She stood awkwardly, inhaling the smell of mildew lingering beneath cleaners. Asked to wait in a toilet! She needed to leave but was not quite sure how to manage it. She perched on the edge of a claw-footed bathtub, ankles neatly crossed. Five minutes passed, then ten.

At last the door opened with a click and a woman walked in. She was older than Marie by at least a decade, maybe two. Her face was grave. At first her dark hair appeared to be short, but closer Marie saw that it was pulled tightly in a bun at the nape of her neck. She wore no makeup or jewelry, and her starched white shirt was perfectly pressed, almost military.

“I’m Eleanor Trigg, Chief Recruitment Officer. I’m sorry for the accommodations,” she said, her voice clipped. “We are short on space.” The explanation seemed odd, given the size of the house, the number of doors Marie had seen. But then she remembered the man whom the butler seemed to chastise for speaking with her. Perhaps the people who came here weren’t meant to see one another at all.

Eleanor appraised Marie as one might a vase or piece of jewelry, her gaze steely and unrelenting. “So you’ve decided then?” she said, making it sound as if they were at the end of a long conversation and had not met thirty seconds earlier.

“Decided?” Marie repeated, puzzled.

“Yes. You have to decide if you want to risk your life, and I have to decide if I can let you.”

Marie’s mind whirled. “I’m sorry... I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

“You don’t know who we are, do you?” Marie shook her head. “Then what are you doing here?”

“A man in a café gave me a card and...” Marie faltered, hearing the ridiculousness of the situation in her own voice. She had not even learned his name. “I should just go.” She stood.

The woman pressed a firm hand on her shoulder. “Not necessarily. Just because you don’t know why you’ve come, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be here. We often find purpose where we least expect it—or not.” Her style was brusque, unfeminine and unquestionably stern. “Don’t blame the man who sent you. He wasn’t authorized to say more. Our work is highly classified. Many who work at the most senior levels of Whitehall itself have no idea what it is that we do.”

“Which is what, exactly?” Marie ventured to ask.

“We’re a branch of Special Operations Executive.”

“Oh,” Marie said, though the answer really didn’t clarify matters for her.

“Covert operations.”

“Like the codebreakers at Bletchley?” She’d known a girl who had left the typing pool to do that once.

“Something like that. Our work is a bit more physical, though. On the ground.”

“In Europe?” Eleanor nodded. Marie understood then: they meant to send her over, into the war. “You want me to be a spy?”

“We don’t ask questions here,” Eleanor snapped. Then it was not, Marie reflected, the place for her. She had always been curious, too curious, her mother would say, with never-ending questions that only made her father’s temper worsen as Marie progressed through her teen years. “We aren’t spies,” Eleanor added, as though the suggestion was offensive. “Espionage is the business of MI6. Rather, here at SOE, our mission is sabotage, or destroying things like railroad tracks, telegraph lines, factory equipment and such, in order to hinder the Germans. We also help the local partisans arm and resist.”

“I’ve never heard of such things.”

“Exactly.” Eleanor sounded almost pleased.

“But what makes you think I could have any part in something like this? I’m hardly qualified.”

“Nonsense. You’re smart, capable.” How could this woman, who had only just met her, possibly know that? It was perhaps the first time in her life that anyone had described her that way. Her father made sure she felt the very opposite. And Richard, her now-gone husband, had treated her as if she was special for a fleeting moment, and look where all that had led. Marie had never thought of herself as any of those things, but now she found herself sitting a bit taller. “You speak the language. You’re exactly who we’re looking for. Have you ever played a musical instrument?” Eleanor asked.

Though it seemed nothing should surprise her anymore, Marie found the question strange. “Piano when I was very young. Harp in school.”

“That could be useful. Open your mouth,” Eleanor ordered, her voice suddenly terse. Marie was certain that she had misheard. But Eleanor’s face was serious. “Your mouth” came the command again, insistent and impatient. Reluctantly, Marie complied. Eleanor stared into her mouth like a dentist. Marie bristled, resenting the intrusion by a woman she had only just met. “That back filling will have to go,” Eleanor said decisively, stepping back.

“Go?” Marie’s voice rose with alarm. “But that’s a perfectly good filling—just a year old and was quite expensive.”

“Exactly. Too expensive. It will mark you as English right away. We’ll have it replaced with porcelain—that’s what the French use.”

It all came together in Marie’s mind then: the man’s interest in her language skills, Eleanor’s concern over whether a tooth filling was too English. “You want me to impersonate a Frenchwoman.”

“Among other things, yes. You’ll receive training in operations skills before you are deployed—if you make it through training.” Eleanor spoke as though Marie had already agreed to go. “That’s all I can say about it for now. Secrecy is of the utmost importance to our operations.”

Deployed. Operations. Marie’s head swam. It seemed surreal that in this elegant town house just steps from the shops and bustle of Oxford Street, covert war against Germany was planned and waged.

“The car will be here for you in one hour to take you to training school,” Eleanor said, as though it were all settled.

“Now? But that’s so soon! I would have to sort out my affairs and pack.”

“It is always the way,” Eleanor replied. Perhaps, Marie reflected, they didn’t want to give people a chance to go home and have second thoughts. “We’ll provide everything you need and give notice to the War Office for you.” Marie stared at Eleanor with surprise. She hadn’t said where she worked. She realized then that these people, whoever they were, knew too much about her. The meeting in the café had not been by chance.

“How long would I have to be gone?” Marie asked.

“That depends on the mission and a variety of other circumstances. You can resign at any time.”

Leave, a voice not her own seemed to say. Marie was into something much bigger and deeper than she had imagined. But her feet remained planted, curiosity piqued. “I have a daughter up near Ely with my aunt. She’s five.”

“And your husband?”

“Killed in action,” she lied. In fact, Tess’s father, Richard, had been an unemployed actor who had gotten by on parts as extras in West End shows and disappeared shortly after Tess was born. Marie had come to London when she was eighteen, fleeing her father’s home, and had promptly fallen for the first bad apple that dropped at her feet. “He went missing at Dunkirk.” The explanation, a morbid lie, was preferable to the likely truth: that he was in Buenos Aires, spending what was left of her mother’s inheritance, which Marie had naively moved to a joint account to cover their household expenses when they had first married.

“Your daughter is well cared for?” Marie nodded. “Good. You would not be able to concentrate on training if you were worried about that.”

She would never stop worrying about Tess, Marie thought. She knew in that instant that Eleanor did not have children.

Marie thought about Tess up in the countryside, the weekend visits that wouldn’t happen if she accepted Eleanor’s proposal. What kind of mother would do such a thing? The responsible choice would be to stay here in London, to thank Eleanor and go back to whatever ordinary life was left during the war. She was the only parent Tess had. If she failed to come back, Tess would have no one but aging Aunt Hazel, who surely couldn’t look after her much longer.

“The work pays ten pounds per week,” Eleanor added.

That was five times what Marie made typing. She’d found the best work she could in London, but it hadn’t been enough. Even combined with a second job, the kind that would have kept her from getting up to see Tess at the weekends, she would not have made what Eleanor was offering. She did the calculations. She would have enough to keep up the house even after sending money to Hazel each week to cover Tess’s care and expenses, something that simply was not possible now. She imagined a new dress for her daughter, perhaps even a few toys at Christmas. Tess was unspoiled and never complained, but Marie often wished to give her more of the things she had taken for granted in her own childhood. It wasn’t like she could be with Tess now while she was stuck working in London anyway. And, in truth, Marie was curious about the mysterious adventure Eleanor was dangling in front of her. She felt so useless sitting here in London, typing endlessly. Might as well do some good, make a real difference in the war effort—if, as Eleanor had said, she in fact had what it took.

“All right then. I’m ready. But I have to phone and let my daughter’s caretaker know that I won’t be coming up.”

Eleanor shook her head firmly. “Impossible. No one can know where you are going—or even that you are going. We’ll send a telegram informing your family that you’ve been called away for work.”

“I can’t simply leave without saying anything.”

“That is exactly what you must do.” Eleanor stared at her evenly. Though her expression did not change, Marie saw a flicker of doubt behind her eyes. “If you aren’t prepared to do this, you can just leave.”

“I have to speak to my daughter. I won’t go unless I can hear her voice.”

“Fine,” Eleanor relented finally. “But you cannot tell her that you are going. There’s a phone in the next room you can use. Keep it brief. No more than five minutes.” Eleanor spoke as though she was in charge of Marie now, owned her. Marie wondered if accepting had been a mistake. “Say nothing of your departure,” Eleanor reiterated. Marie sensed it was some sort of test—perhaps the first of many.

Eleanor started for the door, indicating that Marie should follow. “Wait,” Marie said. “There’s one thing.” Eleanor turned back, the start of annoyance creeping onto her face. “I should tell you that my father’s family is German.” Marie watched Eleanor’s face, half hoping the information might cause Eleanor to change her mind about accepting Marie for whatever she was proposing.

But Eleanor simply nodded in confirmation. “I know.”

“But how?”

“You’ve sat in that same café every day, haven’t you?” Marie nodded. “You should stop that, by the way. Terrible habit. Varying one’s routine is key. In any event, you sit there and read books in French and one of our people noticed and thought you might be a good recruit. We followed you back to work, learned who you are. We ran you through the cards, found you qualified, at least for initial consideration.” Marie was stunned; all of this had been going on and she’d had no idea. “We have finders, recruiters looking for girls who might be the right sort all over Britain. But in the end I decide if they are the right sort to go. Every single one of the girls passes through me.” There was a note of protectiveness in her voice.

“And you think I do?”

“You might,” Eleanor said carefully. “You’ve got the proper credentials. But in training you’ll be tested to see if you can actually put them into use. Skills on paper are useless if you don’t have the grit to see it all through. Do you have any political allegiances of your own?”

“None. My mother didn’t believe in...”

“Enough,” Eleanor snapped. “Don’t answer a question with any more than you have to.” Another test. “You must never talk about yourself or your past. You’ll be given a new identity in training.” And until then, Marie thought, it would be as if she simply didn’t exist.

Eleanor held open the door to the toilet. Marie walked through into a study with high bookshelves. A black phone sat on a mahogany desk. “You can call here.” Eleanor remained in the doorway, not even pretending to give her privacy. Marie dialed the operator and asked to be connected to the post office where Hazel worked each day, hoping she had not yet gone home. She asked for Hazel from the woman who answered.

Then a warbling voice came across the line. “Marie! Is something wrong?”

“Everything’s fine,” Marie reassured quickly, so desperately wanting to tell her the truth about why she had called. “Just checking on Tess.”

“I’ll fetch her.” One minute passed then another. Quickly, Marie thought, wondering if Eleanor would snatch the phone from her hand the moment five minutes had passed.

“Allo!” Tess’s voice squeaked, flooding Marie’s heart.

“Darling, how are you?”

“Mummy, I’m helping Aunt Hazel sort the mail.”

Marie smiled, imagining her playing around the pigeonholes. “Good girl.”

“And just two more days until I see you.” Tess, who even as a young child had an acute sense of time, knew her mother always came on Friday. Only now she wouldn’t be. Marie’s heart wrenched.

“Let me speak to your auntie. And, Tess, I love you,” she added.

But Tess was already gone. Hazel came back on the line. “She’s well?” Marie asked.

“She’s brilliant. Counting to a hundred and doing sums. So bright. Why, just the other day, she...” Hazel stopped, seeming to sense that sharing what Marie had missed would only make things worse. Marie couldn’t help but feel a tiny bit jealous. When Richard abandoned her and left her alone with a newborn, Marie had been terrified. But in those long nights of comforting and nursing an infant, she and Tess had become one. Then she’d been forced to send Tess away. She was missing so much of Tess’s childhood as this bloody war dragged on. “You’ll see for yourself at the weekend,” Hazel added kindly.

Marie’s stomach ached as though she had been punched. “I have to go.”

“See you soon,” Hazel replied.

Fearful she would say more, Marie hung up the phone.

Chapter Four (#ud32e4584-82b1-54e6-9cbe-6d0b6a5f37b3)

Grace

New York, 1946

Forty-five minutes after she had started away from Grand Central, Grace stepped off the downtown bus at Delancey Street. The photographs she’d taken from the suitcase seemed to burn hot against her skin through her bag. She’d half expected the police or someone else to follow her and order her to return them.

But now as she made her way through the bustling Lower East Side neighborhood where she’d worked these past several months, the morning seemed almost normal. At the corner, Mortie the hot dog vendor waved as she passed. The window cleaners alternated between shouting to one another about their weekends and catcalling at the women below. The smell of something savory and delicious wafted from Reb Sussel’s delicatessen, tickling her nose.

Grace soon neared the row house turned office on Orchard Street and began the climb that always left her breathless. Bleeker & Sons, a law practice for immigrants, was located in a fourth-floor walk-up above a milliner and two stories of accountants. The name, etched into the glass door at the top of the landing, was a misnomer because it was just Frankie, and always had been as far as she could tell. A line of refugees fifteen deep snaked down the stairs, hollow cheekbones above heavy coats and too many layers of clothing, as though they were afraid to take off their belongings. Their faces were careworn and drawn and they did not make eye contact. Grace noticed the unwashed smell coming from them as she passed, and then was immediately ashamed at herself for doing so.

“Excuse me,” Grace said, stepping delicately around a woman sitting on the ground with a baby sleeping on her lap. She slid into the office. Across the single room, Frankie perched on the edge of his worn desk, phone receiver cradled between his ear and shoulder. He grinned widely and waved her over.

“I’m sorry I’m late,” she said as soon as he hung up the phone. “There was an accident by Grand Central and I had to go around.”

“I moved the Metz family to eleven,” he said. There was no recrimination in his voice.

Closer she could see the imprint of papers creasing his cheek. “You were here all night again, weren’t you?” she accused. “You’re wearing the same suit, so don’t try to deny it.” She immediately regretted the observation. Hopefully, he would not realize the same about her.

He raised his hands in admission, touching the spot near his temples where his dark hair was flecked with gray. “Guilty. I had to be. The Weissmans needed papers filed for their residency and housing.” Frankie was tireless when helping people, as though his own well-being did not matter at all.

“It’s done now.” She tried not to think about what she had been doing while he had been working all night. “You should get some sleep.”

“Don’t lecture me, miss,” he chided, his Brooklyn accent seeming to deepen.

“You need rest. Go home,” she pressed.

“And tell them what?” He gestured with his head toward the line of people waiting in the hallway.

Grace looked back over her shoulder at the never-ending stream of need that filled the stairwell. Sometimes she was overwhelmed by all of it. Frankie’s practice consisted mainly of helping the European Jews who had come to live with relatives in the already teeming Lower East Side tenements; it sometimes felt more like social work than law. He took all of their cases, trying to find their relatives or their assets or get them citizenship papers, often for little more than a promise of payment. He had never missed her salary, but she sometimes wondered how he kept up the lights and rent.

And his own health. His white shirt was yellowed at the neck and he was covered as always in a fine layer of perspiration that made him seem to glow. A lifelong bachelor (“Who would have me?” he’d joked more than once) approaching fifty, he was a dilapidated sort, five-o’clock shadow even at ten in the morning and hair seldom combed. But there was a warmth to his brown eyes that made it impossible to scold and his quick smile always brought out her own.

“You need to at least eat breakfast,” she said. “I can run and get you a bagel.”

He waved away the suggestion. “Can you just find me the number for social services in Queens?” he asked. “I want to freshen up before our first meeting.”

“You’ll do our clients no good if you make yourself sick,” she scolded.

But Frankie just smiled as he started out the door for the washroom. He ruffled the hair of a young boy who sat on the landing as he passed. “Just a minute, okay, Sammy?” he said.

Grace picked up the ashtray from the corner of his desk and emptied it, then wiped the top of the table to clear away the dust left behind. She and Frankie had, in a sense, found each other. After she had taken the narrow room with a shared bath off Fifty-Fourth Street close to the West River, she’d quickly run through what little money she had and started to look for a job, armed with no more than a high school typing class. When she’d gone to answer an ad for a secretary for one of the accountants in the building, she had walked into his law office by mistake. Frankie said he’d been looking for someone (whether or not that was the case, she would never actually know) and she’d started the next day.

He didn’t really need her to work there, she quickly came to realize. The office was tiny, almost too small for the both of them. Though his papers were seemingly tossed in haphazard piles, he could put his fingers on a single page he needed within seconds. The work was hectic, but he could do it all by himself; in fact, he had been doing it all for years. No, he hadn’t needed her. But he sensed that she needed the job and so he had made a place. She loved him for it.

Frankie walked back into the office. “Are you ready?” he asked. She nodded, though she still wanted to go home for a bath and a nap, or at least find coffee. But Frankie was headed purposefully toward his desk with the young boy from the landing in tow. “Sammy, this is my friend Grace. Grace, I’d like to introduce Sam Altshuler.”

Grace looked behind the boy toward the door for the others. She had been expecting a whole family, or at least an adult, to accompany him. “Mother? Father?” she mouthed silently over the boy’s head so he could not see.

Frankie shook his head gravely. “Sit down, son,” he said gently to the boy, who could not be older than ten. “How can we help?”

Sammy looked up uncertainly through long eyelashes, not sure whether to trust them. Grace noticed then a small notebook in his right hand. “You like to write?” she asked.

“Draw,” Sammy replied with a heavy East European accent. He held up the pad to reveal a small sketch of the queue of people waiting on the stairs.

“It’s wonderful,” she said. The details and expressions on the people’s faces were stunningly good.

“How can we help you?” Frankie asked.

“I need sumvere to live.” He spoke the broken but functional English of a smart kid who had taught himself.

“Do you have any family here in New York?” Frankie asked.

“My cousin, he shares an apartment vith some fellas in the Bronx. But it costs two dollars a veek to stay vith them.”

Grace wondered where Sammy had been living until now. “What about your parents?” she couldn’t help asking.

“I vas separated from my father at Vesterbork.” Westerbork was a transit camp in Holland, Grace recalled from a family they had helped weeks earlier. “My mother hid me vith her for as long as she could in the vomen’s...” He paused, fumbling for a word. “In the barracks, but then she was taken, too. I never saw them again.”

Grace shuddered inwardly, trying to imagine a child trying to survive alone under such circumstances. “It’s possible that they survived,” she offered. Frankie’s eyes flashed above the boy’s head, a silent warning.

Sammy’s expression remained unchanged. “They vere taken east,” he said, his voice matter-of-fact. “People don’t come back from there.” What was it like, Grace wondered, to be a child with no hope?

Grace forced herself to focus on the practicalities of the situation. “You know, there are places in New York for children to live.”

“No boys’ home,” Sammy replied, sounding panicked. “No orphanage.”

“Grace, can I speak with you for a moment?” Frankie waved her over to the corner, away from Sammy. “That boy spent two years in Dachau.” Grace’s stomach twisted, imagining the awful things Sammy’s young eyes had seen. Frankie continued, “And then he was in a DP camp for six months before managing to get here by using the papers of another little boy who died. He’s not going to go to another institution where people can hurt him again.”

“But he needs guardians, an education...” she protested.

“What he needs,” Frankie replied gently, “is a safe place to live.” The bare minimum to survive, Grace thought sadly. So much less than the loving family a child should have. If she had a real apartment, she might have taken Sammy home with her.

Frankie started back toward the boy. “Sammy, we’re going to start the process of having your parents declared deceased so that you can receive payments from social security.” Frankie’s voice was matter-of-fact. It wasn’t that he didn’t care, Grace knew. He was helping a client (albeit a young one) get what he needed.

“How long vill that take?” Sammy asked.

Frankie frowned. “It isn’t a quick process.” He reached in his wallet and pulled out fifty dollars. Grace stifled a gasp. It was a large sum in their meager practice and Frankie could hardly afford it. “This should be enough to live with your cousin for a while. Keep it on you and don’t trust anyone with it. Check in with me in two weeks—or sooner if things aren’t good with your cousin, okay?”

Sammy looked at the money dubiously. “I don’t know ven I can repay you,” he said, his voice solemn beyond his years.

“How about that drawing?” Frankie suggested. “That will be payment enough.” The boy tore the paper carefully from the notepad and then took the money.

Watching Sammy’s back as he retreated through the doorway, Grace’s heart tugged. She had read and heard the stories in the news, which came first in a trickle then a deluge, about the killings and other atrocities that had happened in Europe while people here had gone to the cinema and complained about the shortage of nylons. It was not until coming to work for Frankie, though, that she had seen the faces of the suffering and began to truly understand. She tried to keep her distance from the clients. She knew that if she allowed them into her heart even a crack, their pain would break her. But then she met someone like Sammy and just couldn’t help it.

Frankie walked up beside her and put his arm on her shoulder. “It’s hard, I know.”

She turned to him. “How do you do it? Keep going, I mean.” He had been helping people rebuild their lives out of the wreckage for years.

“You just have to lose yourself in the work. Speaking of which, the Beckermans are waiting.”

The next few hours were a rush of interviews. Some were in English, others she translated using all of the high school French she could muster, and still others Frankie conducted in the fluent German he said he had learned from his grandmother. Grace scribbled furiously the notes Frankie dictated about what needed to be done for each client. But in between meetings, Grace’s thoughts returned to the suitcase she had found at the train station that morning. Why would someone simply have abandoned it? She wondered if the woman (Grace assumed it was a woman from the clothing and toiletries inside) had left it inadvertently, or if she knew she wasn’t coming back. Perhaps it was meant for someone else to find.

“Why don’t we break for lunch?” Frankie asked when it was nearly one o’clock. Grace knew he really meant that she should take lunch, while he would keep working, at most eat whatever she brought back for him. But she didn’t argue. She hadn’t eaten either today, she recalled as she started down the stairs.

Ten minutes later, Grace stepped out onto the flat rooftop of the building where she liked to eat when the weather permitted. It had a panoramic view of Midtown Manhattan stretching east to the river. The city was beginning to resemble one big construction site, from the giant cranes building glass-and-steel skyscrapers across Midtown to the block apartments going up on the edge of the East Village. She watched a group of girls on their lunch hour step out of Zarin’s Fabrics, long-legged and fashionable, despite the years of shortages and rationing. A few even smoked now. Grace didn’t want to do that, but she wished she fit in just a bit. They seemed so sure of their place. Whereas she felt like a visitor whose visa was about to expire at any moment.

Grace wiped off a sooty windowsill and perched on it. She thought of the photos in her purse. A few times that morning, she’d wondered if she had imagined them. But when she’d gone into her purse to fish out some coins for lunch, there they sat, neatly wrapped in the lace. She had wanted to bring them with her and have another look over lunch, but the roof tended to be breezy and she didn’t want them to blow away.

Grace unwrapped the hot dog she’d bought from the vendor, missing the egg salad sandwich she usually packed. She liked a certain order to her world, took comfort in its mundaneness. Now the whole apple cart seemed toppled. With last night’s misadventure, she had moved just one piece out of place (admittedly a very big one, but a single piece nonetheless) and now it seemed that everything was in complete disarray.

Turning her gaze uptown, her eyes locked on the vicinity of a certain high rise on the East River. Though she couldn’t see it, the elegant hotel where she had spent the previous night loomed large in her mind. It had all started innocently enough. On her way home from work, Grace had stopped for dinner at Arnold’s, a place on Fifty-Third Street that she had passed dozens of times, because she didn’t have anything in the shared icebox in the boardinghouse kitchen. She had planned to ask for her meal to go, broiled chicken and a potato. But the mahogany bar, with its soft lighting and low music, beckoned. She didn’t want to sit in her cramped room and eat alone again.

“I’ll have a menu, please,” Grace said. The maître d’s eyes rose. Grace made her way to the bar trying to ignore the looks of the men, surprised to see a woman dining alone.

Then she noticed him, a man at the edge of the bar in a smart gray suit, facing away from her. He had broad shoulders and close-cut, curly brown hair tacked into place with pomade. A long-forgotten interest stirred in her. He turned and rose, his face lifting with recognition. “Grace?”

“Mark...” It had taken a second for her to place him so far out of context. Mark Dorff had been Tom’s college roommate at Yale.

More than Tom’s roommate, she realized as the memories returned. His best friend. Though two years older than Tom, Mark had been a constant presence among the sea of boys in navy wool blazers at events, and at the homecoming dances. He had even been an attendant in her wedding. But this was the first time they had really spoken, just the two of them.

“I didn’t realize that you were living in New York,” he remarked.

“I’m not. That is, sort of.” She fumbled for the right words. “I’m here for a time. And you?”

“I’m living in Washington. I was here for a few days for work, but I’m headed back first thing tomorrow. It’s good to see you, Gracie.” She had always disliked the nickname her family had given her, that Tom had picked up for his own. It felt diminutive, designed to keep her in her place. But now there was a kind of warmth to hearing it that she realized she had missed during her months alone in the city. “How are you?”

There it was, the question she dreaded most since Tom’s death. People always sounded as though they were trying to get the level of sympathy in their voices just right, to ask in a personal-but-not-too-personal way. Mark looked concerned, though, like he really meant it. “That’s such a stupid thing to ask,” he added when she did not answer. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s fine,” she said quickly. “I’m managing.” In truth, it had gotten easier. Being in New York and not seeing the places that would remind her of Tom every day allowed her to put it behind her, at least for a time. That numbness, that kind of forgetting, was part of what had driven her to New York. Yet she felt guilty for having found it.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t be at the funeral. I was still overseas.” He dipped his chin. His features were not perfect, she noticed then. Hazel eyes a bit too close together, chin sharp. But the way they fit together was handsome.