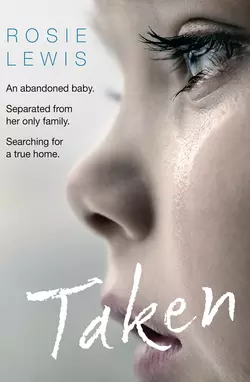

Taken

Rosie Lewis

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Семейная психология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 481.09 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Experienced foster carer, Rosie Lewis, takes on the heart-breaking case of Megan, a baby born with a drug addiction and a cleft palate.Addicted to drugs from birth because of her mother’s substance abuse during pregnancy, new-born Megan is taken into Rosie’s loving care. Rosie is supposed to help Megan find her new permanent home, but it turns out that Megan has already found her ‘forever mummy’ in Rosie.Rosie grows incredibly attached to Megan and applies to adopt her, but the system refuses her in favour of a young couple and Rosie is devastated. Against all her instincts, Rosie does her job and prepares Megan for her new ‘forever family’, but everything about Megan leaving feels wrong.When Rosie learns a few months later that Megan’s adoption has broken down, she is saddened but also filled with hope – will this little girl be allowed to return to her true ‘forever home’?