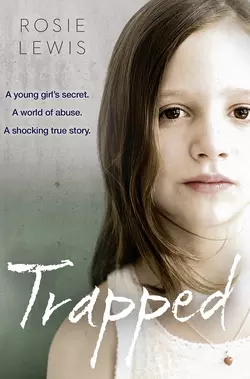

Trapped: The Terrifying True Story of a Secret World of Abuse

Rosie Lewis

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Социология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 577.47 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Trapped was a Sunday Times bestseller and the first memoir from foster carer Rosie Lewis.Phoebe, an autistic nine-year-old girl, is taken into police protection after a chance comment to one of her teachers alerts the authorities that all might not be what it seems in her comfortable, middle-class home. Experienced foster carer Rosie accepts the youngster as an emergency placement knowing that her autism will represent a challenge – not only for her but also for the rest of the family.But after several shocking incidents of self-harming, Pica and threats to kill, it soon becomes apparent that Phoebe’s autism may be the least of her problems.Locked for nine years in a secret world of severe abuse, as Phoebe opens up about her horrific past, her foster carer begins to suspect that Phoebe may not be suffering from autism at all.