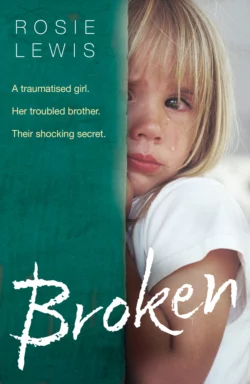

Broken: A traumatised girl. Her troubled brother. Their shocking secret.

Rosie Lewis

Nine-year-old Archie and his five-year-old sister, Bobbi, are taken into emergency police protective custody after an incident of domestic violence at their family home.Rosie collects the children from their out-of-hours foster carer on New Year’s Day and instantly recognises Archie from a domestic violence workshop she helped with. Rosie remembers that when asked what he enjoyed most about the course, Archie said: ‘the biscuits’.Social workers are concerned that Archie and Bobbi have been neglected. As Rosie gets to know the children, she begins to suspect that something far more disturbing lies in their past.Archie, jovial and polite, bats away Rosie’s attempts to talk to him about anything serious with witty one-liners and sophisticated distractions. Bobbi reacts violently, lashing out and throwing herself around. Rosie has never seen a child as young a Bobbi behaving so viciously, but it is Archie she is most concerned about as the weeks go by.After a worrying incident at school, Archie tearfully discloses the truth – a shocking secret that has left him and his sister traumatised. Horrified at what she learns, Rosie is determined to help the young siblings find a forever-home that will provide them with the love and care they deserve.

(#u0a4d892e-db9d-5747-96fe-08829501e9c2)

Copyright (#u0a4d892e-db9d-5747-96fe-08829501e9c2)

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2017

FIRST EDITION

© Rosie Lewis 2017

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers

Cover photograph (posed by model) © Images by Tracy/Alamy Stock Photo

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Rosie Lewis asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008242800

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780008242817

Version: 2018-11-05

Contents

Cover (#ubb869110-e3e1-5394-b980-e775d483ee3c)

Title Page (#u2c4f7b8e-35f0-52e4-bd58-1c54e9d001e2)

Copyright (#u02627150-acb3-5e04-9535-b6e020706bd8)

By the same author (#ud071f10c-8012-5bc8-96c4-1e5009eae6c5)

Prologue (#ud071f10c-8012-5bc8-96c4-1e5009eae6c5)

Chapter One (#u7efc1c48-df40-5181-b159-a1d0073dbad6)

Chapter Two (#u00c455e9-af1e-586d-a35f-0df46278193e)

Chapter Three (#uf6a79be5-77c1-5213-91e9-5b4b7f6f1831)

Chapter Four (#u628969a0-35c3-50e4-91e7-20b16f830dcd)

Chapter Five (#uc0e16525-e265-5c5e-bf6c-bcc0fa5db50d)

Chapter Six (#u93c290e9-ee34-59fd-bb05-4d35f53acb39)

Chapter Seven (#u393b9a0f-f0ab-525c-974e-08924ce82425)

Chapter Eight (#ub34c2465-ea0c-590b-8527-1462f2037ae4)

Chapter Nine (#ud289a200-175c-5561-9d51-314ced5f1084)

Chapter Ten (#u64ef020b-e114-5c7d-ad8f-2ca3ee7010ec)

Chapter Eleven (#ua9af0e29-63fb-51b5-ae48-09297bf9d9dd)

Chapter Twelve (#ua31b0dee-1ea0-5765-8e15-8aa2b95c5714)

Chapter Thirteen (#u38d4578c-c5b3-5d37-b8f7-590d45a1b8bd)

Chapter Fourteen (#u4a2514f5-b10a-5b00-8ffe-a7ef17811232)

Chapter Fifteen (#u69d541b9-4847-5ac2-8b97-8379a037e93c)

Chapter Sixteen (#u7c288214-84e0-51d6-a1b8-cd4a002c5e67)

Chapter Seventeen (#u75c9dcdc-3cf5-5764-957c-aa74818063bf)

Chapter Eighteen (#u377aeab9-e9ef-52f1-b585-433b56ccff4e)

Chapter Nineteen (#ub84a4af3-4cb0-5ffa-8040-e06e6442b383)

Chapter Twenty (#u4866c8a3-2ccf-5e92-96e2-f933a97d1f62)

Chapter Twenty-One (#u37a4d950-6cec-5715-b1ab-f93640550c7d)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#u4ea62133-4b7d-5d3e-b7ea-8732bf0d39ac)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#u2272b283-4cd6-5717-a43d-d4cf66f11fe8)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#u412fc3cc-71b5-5c47-b155-07d359756268)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#uc63743db-dc7c-585e-a47a-9971666f49ca)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#uce459e2f-6c3e-5e53-a558-2117dd08da3c)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#u92811559-c964-5dc1-bc45-7b9e778fff6f)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#ud67196e8-7035-5af2-be38-6d52af0736a9)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#u22c626f4-92b1-5049-a5f1-0a85fe8d23d4)

Epilogue (#u00a58299-3dcc-505d-8b59-9262f3ec2bef)

Helpful Reading (#u1706e413-c544-5cae-8f2f-6908911cfef2)

Also available (#u1a3b34d7-2d90-56f6-acd1-1c549d9fcc51)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#u32c52533-0fc4-54a0-bf0e-18b23249c92f)

About the Publisher (#ub622c207-6baf-508b-8b84-af50d5a341c4)

By the same author (#u0a4d892e-db9d-5747-96fe-08829501e9c2)

Helpless (e-short)

Trapped

A Small Boy’s Cry (e-short)

Two More Sleeps (e-short)

Betrayed

Unexpected (e-short)

Torn

Taken

Prologue (#u0a4d892e-db9d-5747-96fe-08829501e9c2)

July 2014

Archie opens his eyes and blinks. For a second he wonders where he is, then he realises and his tummy flips over. Something hard is digging in his side. It feels cold and pointy, like one of his Transformers. There’s something wrong with his back as well. Not an ache exactly, but it feels funny and wrong.

Cold, that’s what it is. He tries rolling over but a pain shoots down his shoulder and his head begins to hurt. It feels as if his skin is stuck to the wooden floor. Where’s his top? He can’t remember taking it off but his brain is fuzzy. He shakes his head and tries to think. If he can just get back to his room, maybe he can work it out. There’s a clinking noise as he tries to roll again. He freezes and holds his breath. As his eyes adjust to the half-light he realises there’s a pile of empty glass bottles wedged between his body and the bed.

He begins to ease himself away but stops suddenly and cocks his head. Someone is snoring, someone close by, and there are other sounds as well. Softer sounds. Like people breathing in and out. How many, he can’t tell. He tries to keep track but all the sounds keep tripping over each other and mixing him up.

If there are just two or three of them he might risk creeping back to his room – he wants to check that Bobbi’s okay – but if there are more and one of them wakes up … no, he can’t chance it. Not after what happened before.

If only he could decide what to do.

And then it starts. A stirring. A swishing noise, then a thud. A wire of fear flashes through his tummy. Strange scary shadows rise above him and he holds his breath, shrinking back into the cold floor.

The shapes move over one another, two, then three, then more. All making a tangled, groaning mess. There’s a strange smell as well. Sweat and booze and something musty that makes his throat burn. Then he hears a woman’s voice. She sounds sad, frightened. His stomach lurches and there’s a vile taste in his mouth. All he wants to do is run back to his room and to Bobbi. With a stab of shame, he realises that he’s too frightened to move.

The shadows and the noises, they make him feel sick, make his tummy roll. Somehow, though, he can’t tear his eyes away. Biting down on his lower lip, silent tears roll down his cheeks.

Chapter One (#u0a4d892e-db9d-5747-96fe-08829501e9c2)

‘You can’t miss it, love,’ the elderly gentleman assured me, pointing towards the complicated one-way system I’d just escaped from. It was New Year’s Day 2015 and I was on my way to meet a nine-year-old boy named Archie Brady and his five-year-old sister, Bobbi. The siblings had been temporarily accommodated by Joan Oakley, a foster carer who had accepted the referral four days earlier. ‘Follow the road round as far as the greengrocer’s then take an immediate left. Straight over the next roundabout, under the railway bridge and Bob’s your uncle.’

I thanked him distractedly, trying to get my bearings. I performed a U-turn on the icy road, hoping that this time I wouldn’t get tangled up in the endless maze of side streets around the town centre. It was already 10 a.m. and I wanted to have a quick handover chat with Joan and make it back home before lunchtime. One thing I’ve learned over the last twelve years of fostering is that car journeys and fretful children are a toxic mix. Adding hunger to the equation would be a bit like tossing a stick of dynamite into the interior of my Fiat and hoping for the best.

The children were bound to feel uncertain about another move so quickly after the last and I wanted to do everything I could to lessen their anxiety. It’s generally acknowledged that any change in carer should take place as early in the day as possible. That way the child has a chance to acclimatise to their new surroundings before climbing into an unfamiliar bed.

Joan was keen to bring an end to the unexpected placement as well, by all accounts. ‘She’s tearing her hair out’ were the actual words the social worker from the placements team used when I spoke to her the day before. Apparently Joan already had her hands full caring for a baby with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). She had agreed to take the siblings as a favour after the out-of-hours team had been unable to get hold of the foster carer on their emergency rota.

Like me, Joan was a short-term or task-based foster carer. Our ‘job’ is a temporary one but placements can last anything from one night to four years. Short-term foster carers support the child from the moment they’re removed from home and through the uncertain stage when their birth family is being assessed by the local authority. Once a final judgment has been made by the courts, foster carers help to manage the child’s transition either back to their birth family or onto permanency with long-term foster or kinship carers or an adoptive family.

At least, being a bank holiday, the roads were free of the usual weekday traffic, and I arrived at Joan’s house a little over ten minutes later. As I walked across her driveway, where a Ford Focus full of child car seats was parked, my eye was drawn by the flicker of a curtain at one of the windows on the second floor. I looked up as I rang the doorbell and caught a glimpse of blonde hair.

‘Rosie, you’re just how I pictured you,’ Joan said warmly, holding the door open with one hand, the other cradled around the small bump strapped to her chest. Around sixty or so, Joan wore a cheery expression, despite the dark circles under her eyes. We had never met before, but knew of each other through a social worker who worked at Bright Heights, the fostering agency I was registered with. I had heard that Joan was a well-respected carer and rarely had a vacancy.

‘Sounds ominous,’ I joked as I wiped my feet on the doormat. Joan smiled and bobbed her way along the hall to the sitting room. It was a routine I’d been through several times before with newborns who were withdrawing from drugs. Babies with substance addiction – known as neonatal abstinence syndrome – often need the constant comfort of a cuddle during their first few weeks of life because the pain of withdrawal, the jitters, stomach cramps and fever can be intense.

The sitting room was cosy, the lights woven around the mantelpiece casting a cheery glow on the peach-coloured walls. There was no sign of the siblings, but distant chatter and a thump overhead suggested they were upstairs. I nodded towards her middle. ‘You’ve got a tiny one there.’

She eased the sling down an inch. I caught a glimpse of dark hair and the tiny curve of a delicate ear before the baby began to squall and Joan was on the move again. ‘Two weeks old and still only five pounds,’ she said, swinging her shoulders from side to side. ‘I heard you’d adopted recently. Megan, isn’t it? How’s she doing?’

News travelled with surprising speed around fostering circles. When Megan’s adoption was finalised in June 2014, I had been touched to receive congratulatory cards from lots of foster carers, some of whom I had only met once or twice. Like Joan’s new charge, Megan, now three and a half, had been born addicted to drugs. She suffered painful withdrawal symptoms and was barely out of my arms during her first few weeks of life.

Like me, my birth children, Emily and Jamie, then sixteen and thirteen, had grown increasingly attached to her, and vice versa. When Megan’s social worker suggested that I throw my hat into the ring for assessment as her adopter, I had jumped at the chance. ‘She’s a right little pickle,’ I said, remembering this morning’s meltdown over a major misdemeanour of mine – cutting her toast into triangles instead of squares. ‘But she’s our little pickle. We wouldn’t be without her now.’

The pouches beneath Joan’s eyes creased as she smiled. ‘I heard it was touch-and-go for a while.’

I blew out some air and nodded. It was true. After being turned down as an adopter for Megan because of safety concerns (her birth family knew where I lived), we went through the difficult process of moving her onto adoptive parents. The placement broke down and she returned to us a few weeks later, but the move had left its mark. Megan was still fearful of separation, even for short periods. Getting her settled at nursery in September had been a challenge. For the first few weeks she became so distressed at drop-off time that I decided to stay with her.

By the end of the winter term she was managing four mornings and one longer day a week on her own, but still clung to me before she went in. Fortunately the staff were amazing. They grew teary when I explained Megan’s background and always made an extra special effort to welcome her. ‘To be honest I forget she’s adopted most of the time.’

Joan smiled. ‘Make yourself comfortable, if you can find a space. You won’t mind if I don’t join you?’

‘Knock yourself out,’ I said with a chuckle, and then, ‘Oh dear, Joan, your poor back.’ I couldn’t actually find a space to sit down. Strewn across the sofa were several half-opened packets of wet wipes, a few unused nappies, a cellular blanket, a couple of children’s magazines and various other toys. ‘I’ll perch here, shall I?’ I gestured to the arm of the sofa.

She grimaced. ‘Sorry, Rosie. But you know how tough it is.’

I waved her apology away. ‘Joan, you’re dressed. That’s a miracle in itself.’

She came to a stop a few feet in front of me and gave me a grateful smile. ‘Talking of tough … you’re looking for a new challenge, are you?’

‘Ha, well … how much of a challenge are we talking about?’

She blew out some air. ‘Have you ever seen Armageddon?’

I laughed. ‘Oh, Joan, don’t.’ She didn’t laugh back, just half-cocked an eyebrow. ‘What? That bad?’

‘Put it this way,’ she said, glancing at the door and lowering her voice. ‘I’ve only had them a few days and I’ve been distracted, so it’s difficult to tell how much is boredom, how much is down to the shock of the move and – well, you’ll see for yourself soon enough. I mean, Archie’s been fairly quiet …’

She stopped at the sound of footsteps. Moments later a young girl burst into the room. As soon as she caught sight of me she came straight over and laid her head on my lap. My stomach clenched with pity. I glanced at Joan. She gave me a meaningful look and said something inaudible out of the corner of her mouth.

Being overfamiliar with strangers isn’t unusual behaviour for children from chaotic backgrounds. While some children with a history of trauma and neglect withdraw into themselves, others trust no one to keep them safe and take matters into their own hands. Bobbi was probably trying to minimise any threat I posed by making herself appear both appealing and vulnerable. It was the reptilian part of her brain at work; her own little fight for survival. ‘Hello. You must be Archie?’

She lifted her head. ‘Huh?’

I gave her a teasing smile. ‘Pleased to meet you, Archie.’

She giggled. ‘I’m not a boy! I’m Bobbi!’ She was a pretty girl with deep-set brown eyes and pale, barely-there eyebrows. Her complexion was pallid though, and she looked far too thin.

‘Oh, of course you are,’ I said, smiling. ‘Silly me.’ There was a flicker of movement across the room. I half-registered a boy standing in the doorway. ‘This must be your sister then?’

As I turned towards him I was struck by a flash of recognition. I ran my eyes over his wavy brown hair and the pale skin of his thin face and then I remembered where I’d seen him before. I had helped out on a domestic violence workshop for children a few months earlier and Archie had been one of the attendees. He had stuck in my mind because when the social worker asked the children at the end of the session what they had enjoyed most about the course, Archie had answered, ‘The biscuits.’

Already classed as ‘children in need’ by the local authority following episodes of domestic violence between their mother and her partner, the comment had heightened professionals’ concerns over the siblings’ welfare, particularly as both were very small for their respective ages. As many as three children die each week in the UK through maltreatment and the biscuits comment, while far from definitive proof of neglect, was certainly something to jangle already twitching nerves.

I decided not to say anything about recognising him. He certainly didn’t need reminding of his past – ‘Coo-ee! I was there when you were at one of the lowest points in your life. Remember me?’

‘Archie,’ Joan said. ‘This is Rosie, love.’

He took a few steps into the room, his sister giggling a high-pitched cackle in front of me. ‘I think I know you. Weren’t you on that course I went to?’

‘Yes, that’s right. Lovely to see you again, Archie. You’re both coming to stay with me, then?’ They nodded in unison, Bobbi beginning to spin around on one leg. ‘That’s good. My children can’t wait to meet you.’

‘How many have you got?’ Archie asked as Bobbi lowered her head back to my thigh. Singing loudly, she grabbed the arm of the sofa and began running on the spot, head-butting me in the process. I put a hand on each of her shoulders and gently eased her away. She frowned at me then threw herself backwards onto a nearby footstool and made loud panting noises.

‘I have two daughters,’ I said, ignoring the sideshow and focussing my attention on Archie. For a brief second I pictured myself through his eyes; a woman in her mid-forties with shoulder-length, wavy blonde hair and hazel, slightly tired eyes, ones that hopefully displayed the promise of kindness. ‘Emily is twenty and studying to be a nurse, Megan’s going to be four in July, and then there’s Jamie. He’s seventeen.’

‘I want to be a nurse, Joanie!’ Bobbi shouted from the footstool. ‘Joanie, Joanie, I’m going to be a nurse one day!’

I decided now was as good a time as any to mention the new love in our lives and the latest addition to our family – a six-month-old pup whom Megan had named Mungo. A mongrel pup with some Spaniel and, I suspected from all the holes he’d dug in the garden, some Terrier as well, he was almost as effusive in his affection as little Megan. Although we all loved animals, I had resisted getting a pet because Jamie suffered from asthma. His symptoms had lessened over the years though, and so a few months ago we decided to take the plunge. ‘We also have a dog who’ll be very pleased to meet you,’ I said, aware that Joan was trying to calm Bobbi, who didn’t seem open to the idea at all. Alternately barking and lapping open-mouthed at the air, it was as if Joan wasn’t even there.

Archie smiled when I told him Mungo’s name, though his eyes kept an expressionless quality, as if they weren’t quite plugged in with the rest of him. ‘Does your son like football?’

‘Yes. He loves cricket and rugby as well. How about you?’

He nodded sombrely. ‘I support Man U.’

Before I could respond, Bobbi bolted off the foot stool and charged at him. Head down, she rammed him in the groin with such ferocity that he staggered backwards and clonked his head on the wall. He yelped, arms flailing as he struggled to regain his balance. Then, in a display of what I considered to be remarkable self-constraint, he gave her a mild push in the chest and then cradled his head, his other hand clamped to his groin.

I winced. Joan marched forwards. ‘What have I told you, Bobbi?’ she said crossly. ‘You mustn’t keep lashing out like that!’

Bobbi looked vacant, as if nobody had said a word. Joan took another step towards her and leaned close. ‘Bobbi! Did you hear me?’ she demanded. From her middle came the tiniest mewing sound. Joan straightened, shifting once again from one foot to the other. ‘Poor Archie, look, you’ve hurt him. Say sorry. NOW please!’

‘S’alright, Joan,’ Archie said, still rubbing the back of his head. ‘She didn’t mean it.’

‘Hmm, I’m not so sure about that.’ Joan puffed out some air. ‘Bobbi, upstairs. Fetch your things.’

After a resentful glance at her brother, Bobbi turned and stalked from the room. Archie rolled his eyes and limped after her. Joan gaped at me, her hand flapping towards the door. ‘Did you see that?! I don’t believe it!’

‘What? The head-butt?’

She snorted. ‘No, I can believe that alright. I can’t believe she actually did what I asked.’

I looked at her. ‘The placing social worker said you’re thinking ADHD.’

‘Yes, wouldn’t surprise me,’ Joan said. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a prevalent condition in fostered children. Latest research suggests that there may be a genetic link and one emerging theory is that undiagnosed sufferers turn to drugs in an unconscious attempt at self-medication. It’s one of the reasons I feel sorry for birth parents who lose their children through substance addiction, although my sympathy never extends to those who have been deliberately cruel or abusive. ‘She’s all over the place from morning till night,’ Joan continued. ‘Can’t keep still for a second. Can’t stop fretting about food either, poor little lamb. She can’t sleep. And when she blows, well, you’ll need to dive for cover. She never stops making a noise. I mean, literally never. She’s a little tea leaf as well.’

‘Oh?’

Joan nodded. ‘Yep. Pinches anything that’s not screwed down. And she bites.’

I nodded slowly, absorbing her words. This placement was certainly going to be lively. ‘And Archie?’

She thought for a moment. ‘I haven’t quite worked him out yet. He’s polite enough, I’ll give you that. And on the whole he’s been quiet.’

‘Yes, you’ve said.’

She nodded, glancing down at the baby.

‘What is it, Joan?’

She frowned. ‘I’m not sure,’ she said, giving me a long steady look. ‘Be careful is what I’m saying, I suppose, with your little one around.’

I stared at her for a moment and then glanced away. My eyes were drawn to a lopsided Christmas tree draped with cracked baubles and balding tinsel. It was leaning cheerlessly against a side table, as if all the socialising of the festive season had literally drained the life out of it. Joan noticed my interest. ‘One of Bobbi’s recent victims,’ she said soberly. I laughed, but she shook her head woefully. ‘I’m not joking, Rosie. Be ready to hit the ground running. You’re in for a bumpy ride.’

If I’m honest her words did worry me a little, but perhaps not as much as they should have.

Chapter Two (#u0a4d892e-db9d-5747-96fe-08829501e9c2)

‘You got food at your house, miss, have you? Have you got food?’

‘It’s Rosie. And yes, don’t worry, we have plenty of food.’

‘Cos I like bread and chocolate spread and crisps, have you got some? Have you, Rosie? Have you?’

‘Yes, Bobbi, we –’

‘I like jam as well but not peanut butter, I hate that. Have you got jam, Rosie? Have you got any jam?’

And so it continued all the way home. She was a nervous passenger, startling every time I applied the brake, craning her head and strumming the window as we stopped at each red light. When we went over a sleeping policeman she clutched at the headrest in front of her and held on for dear life. My heart went out to her. She really was an anxious little girl. I glanced at her brother in the rear-view mirror. He sat gazing out of the window, quietly self-contained. I should have been grateful for his calm, but there was something unsettling about the glazed look in his eyes. I felt relieved when he finally spoke. ‘Shut it, Bobbi,’ he said, but mildly. I don’t think she heard him. She certainly didn’t react, or listen when I tried to get a response in.

I suspected that her constant chatter was another sign that her reptilian brain stem was in control of her thinking, trying to ensure her survival by reminding me that she needed attention. I felt sad to think that a little girl had been so poorly treated that she feared for her life. That said, I also wondered how my three were going to react to her constant chatter.

The roads narrowed as we neared home; a typical Edwardian semi-detached house of red brick in the north of England, with a windswept garden and a river beyond. Our surrounding towns are lively enough to keep the youngsters interested once they hit their teens, but small enough to retain some of their old-world charm.

‘Here we are,’ I said cheerfully over the top of Bobbi’s monologue. I pulled up outside our house and peered through the windscreen. Emily was holding Megan up at the living-room window. I waved as I got out of the car and Megan jumped up and down in Emily’s arms. ‘Looks like we have a welcoming committee,’ I said as I opened one of the rear doors and helped Bobbi release her seatbelt. Archie climbed out the other side, threw his rucksack over his shoulder and came to stand beside me.

‘I can do it,’ Bobbi said, refusing my proffered hand and slinking out of the seat herself. As soon as her feet touched the driveway, Megan appeared in front of her, a big beaming smile on her face. Mungo skidded over as well and, just over Bobbi’s hip-height, sniffed excitedly at her armpits and then at her feet.

Bobbi grinned and screamed excitedly. Mungo turned tail and shot off back to the house. A bit taken aback, Megan stared at her for a second, but then reached for her hand. ‘Come and play!’ she chirped, her breath misting the cold air. Bobbi, who was over a year older but only about two inches taller, scowled and shrank away. Megan gave me a bewildered look and my heart lurched. She had been so excited yesterday when I told her that two new children were coming to stay.

Archie leaned over and rested his hands on his knees. ‘Hello, what’s your name?’ he asked engagingly, his whole demeanour softening.

‘Meggie,’ she said with a smile, noticing him properly for the first time.

‘Nice to meet you, Meggie. I’m Archie.’

‘Arty,’ Megan repeated as best she could, a big grin on her face.

‘Hi, Archie,’ Emily said with casual friendliness. She had been welcoming little strangers into our home since she was around eight years old and seemed to have a natural ability for making them feel at ease. Archie flushed and leaned down to stroke Mungo’s floppy brown ears.

Megan made another attempt at grabbing Bobbi’s hand. With her effusive spirit and tactile nature, it was hard for her to comprehend anyone turning down the offer of instant friendship.

‘I know!’ Emily said, eyeing me over the top of the girls’ heads. ‘Let’s go back inside and find some toys for Bobbi.’ She swept Megan up and headed back towards the door.

‘Yay!’ Megan shouted over her shoulder. I felt a swell of gratitude for Emily’s quick thinking. Since Megan’s adoption I had been more careful when considering referrals, only accepting those I was confident would allow me to give her plenty of individual attention. Being born with a cleft palate had left her hard of hearing so she needed more support than other children her age, though she managed well with the use of a hearing aid. Besides struggling with transitions, her exposure to drugs and alcohol in utero had left its mark developmentally. She struggled to learn at nursery, partly because of her hearing difficulties but also because she was easily distracted – a common legacy of exposure to dangerous substances in the womb.

She was a confident girl though, with an awe-inspiring zest for life. She loved the company of other children and was used to fostering – she had grown up with it – but still, she was a vulnerable child with her own set of challenges. I had to bear that in mind.

‘I want fooooood!’ Bobbi whined as I carried their suitcases into the hall. Still wearing her hat, coat and gloves, she charged off up the hall. ‘Where’s the fridge, Rosie? Is it in here? Rosie, is it here?’

‘Come in, love,’ I said to Archie, who was hovering at the open door. I smiled at him. ‘I’ll just see to your sister and then I’ll give you a tour.’

‘Thank you,’ he said politely as I stowed their belongings in front of the stairs. ‘You have a nice house,’ he added as I straightened. I did a double take. Compliments from a child of his age were unexpected, and even more so from someone with a background of domestic abuse. Whenever I accepted a placement I braced myself for verbal insults and even physical abuse. Charming behaviour wasn’t something I’d prepared myself for.

I smiled at him then draped my coat over the banister and went through to the kitchen, where Bobbi had already opened several cupboard doors. ‘Here you are, Bobbi, you can have this for now,’ I said, planting a banana in her hand. I shepherded her out of the kitchen and pulled out one of our dining chairs. She threw herself onto it and immediately began kicking the legs. I bent down and slipped off her shoes. The kicking stopped but almost instantly she began banging her free hand on the table and shouting at the top of her voice.

Her brother appeared at the doorway. ‘Would you like some fruit, Archie? Or do you want to wait for lunch? It won’t be long.’

‘I can wait,’ he said quietly. ‘I need the toilet though.’ At that moment Megan scooted in, carrying a box of Duplo, closely followed by Emily and Jamie.

‘Rosie, Rosie, Rosie!’ Bobbi shouted with a mouth full of banana. She pulled on my top. When I didn’t turn around she picked up one of the placemats from the table and jabbed me in the back with it.

‘Just a minute, Bobbi,’ I said firmly, stepping out of her reach. ‘The bathroom’s straight ahead at the top of the stairs, Archie. This is Jamie, by the way.’

‘Hi, Archie,’ Jamie said easily, as if he were already part of the furniture. And then to me, ‘I’m off to band practice, Mum. See you later.’

Archie, still wearing his rucksack on top of his coat, studied Jamie with interest then followed him up the hall. Emily planted a kiss on my cheek. ‘Sorry to run out on you so quickly, Mum, but I said I’d meet Holly at the library.’ In her middle year of nurse training, Emily spent much of her time off duty from the local university teaching hospital either at the library or bent over the desk in her room.

‘We’ll be fine,’ I said chirpily. I was a big fan of subliminal messages and I was talking as much to the children as to her. I usually muddle through the first few days after children arrive, doing my best to keep a calm environment while everyone adjusts to the changing family dynamics.

Employing foster carers is a snip for local authorities, who have to pay upwards of £5,000 a week if a child is placed in a residential unit or care home. Apart from financial considerations, a care home is usually the last resort for any child. Establishing them in a safe, family environment is the best way for them to build self-esteem as well as a sense of belonging and fair play.

It’s much cheaper for local authorities to place children with their own in-house carers than with those registered with private fostering agencies like Bright Heights, but recruitment challenges mean that it often isn’t possible.

While the allowances I receive as an agency foster carer are on a par with the amounts paid to carers registered with the local authority, the heavy fees charged by the agencies make fostering a profitable business; one of the reasons that hedge-fund investors have been so keen to get involved. It’s a fact I’m uncomfortable with and I’m often tempted to jump ship and transfer to my local authority.

‘Would you two like to do some colouring while I rustle up some lunch?’ I said as Emily and Jamie left.

The suggestion was not to Bobbi’s liking. ‘No, I want food now!’ she shouted, underlining the sentiment by flinging one of the placemats across the room.

It isn’t unusual for fostered children to have issues with food. The digestive discomfort caused by a surge in stress hormones can be difficult to distinguish from hunger pangs, and lots of children seek to cure their ‘funny tummy’ by feeding it. Megan’s exposure to drugs and alcohol had left her with her own digestive difficulties and she suffered with frequent tummy aches, as well as bouts of unexplained sickness. ‘It’s coming very soon, Bobbi. You don’t need to worry; they’ll always be enough food for you here.’ I quickly set out some paper and colouring pens on the table and Megan climbed up onto the chair next to Bobbi.

Thanks to a knock-through by the previous owner our house is open-plan downstairs, so I could see the girls from the kitchen as I prepared some sandwiches. Bobbi chattered continuously as she drew, the noise rising as she washed her hands at the kitchen sink. ‘Rosie, it is ready now? Is it? Is it ready?’

‘Yes, my sweet, it’s here.’ There was still no sign of Archie so as the girls sat next to each other at the table I called up to him.

‘Coming!’ he called back. ‘This looks nice,’ he said when he eventually came down. I smiled at him as he sat next to me but he kept his gaze averted. I noticed a few dark blotches that looked suspiciously like chocolate sticking to his chin and, poking out through the zipped opening of the rucksack at his feet, a shred of clear cellophane wrapping.

‘Rosie, have you got more food in the kitchen?’ Bobbi asked, her faint eyebrows furrowed with anxiety.

I laughed. ‘I have, but we have enough here for now.’ I had placed a platter of nibbles at the centre of the table and sandwiches with a variety of fillings, giving everyone a plate so that they could help themselves. Bobbi already had eight triangles piled high on her plate, as well as some crisps and about ten cherry tomatoes.

She glugged down a cupful of water and picked up two more triangles, squashing them together and ramming them into her mouth. ‘Slow down, sweetie, there’s no rush!’ I said. I preferred not to worry too much about table manners early on in a placement – I usually had plenty of other fish to fry – but Bobbi was almost gagging on her food. I was worried that she might actually choke.

‘We have plenty of food for everyone here,’ I repeated. Her eyes flicked in my direction. She slowed her chewing, but within a few seconds later she had renewed her mission with gusto. Archie ate with less abandon, but had probably already partaken of a starter in the loo.

I remembered reading something about babies and young children who have experienced real hunger internalising the idea that no one will keep them safe. Once hardwired into their brain, it can take years to overwrite such a deeply ingrained belief. A pat on my arm from Megan interrupted my thoughts. ‘Did you see my cloptiker, Mummy?’ she said, pointing to the picture at the top of a pile of drawings at the side of the table.

‘Wow, that’s great, Meggie!’ Already showing a flair for art, she would sit for hours drawing and colouring. She looked at me, her eyes shining with pride.

‘It’s horse shite,’ Bobbi piped up, her voice thick with food. I gave her a sharp glance and looked back at Megan, who, thankfully, seemed not to have heard. Though her hearing difficulties were only mild and her hearing aid helped, she still struggled to make out words when they were muffled.

‘I think it’s cool, Megan,’ Archie chipped in kindly. She beamed.

I gave him a grateful smile then looked at Bobbi. ‘We don’t use rude words like that, Bobbi.’

‘Huh?’ She folded another triangle of bread in half and rammed it into her mouth.

‘I said, you mustn’t use rude words. Say “fiddlesticks” if you can’t think of anything nice to say.’

She swallowed hard and then giggled. Megan laughed too. The pair of them grinned at each other and shouted ‘Fiddlesticks!’ at the tops of their voices. It was the first positive interaction between them and I couldn’t help but smile.

Ten minutes later as I piled the plates together, Bobbi asked for more sandwiches. ‘You’ve had enough for now, sweetie,’ I said gently. ‘But next time you feel hungry, I promise there will be food for you. There’s always fruit, whenever you want it. And we’ll be having dinner in a few hours, okay?’

She scowled at me and went red in the face. I thought she might protest further but, with every last crumb consumed, she agreed to join us for a tour of the house.

Megan led the way upstairs. Mungo waited obediently at the bottom, head cocked with interest. ‘This is my room,’ Megan announced proudly at her open door. ‘None of you are definitely not allowed in here.’

‘Alright, Meggie,’ I said, dropping a hand to her shoulder. Every foster carer is obliged to draw up a Safer Caring policy detailing a set of house rules that every house member must comply with. Designed to keep everyone safe, one of the universal rules is that everyone must stay covered up at all times, whether in pyjamas and dressing gown or fully clothed. Every member of the house must also stay out of every bedroom but their own. Even as the children’s foster carer, I was supposed to knock before entering their room, and should never, under any circumstances, sit on their beds.

Strictly speaking, only the under-fives or same-sex siblings should share bedrooms, but with foster placements in short supply there’s sometimes no alternative but to stretch the rules. I knew that if a vacancy became available with a foster carer who could provide the children with a room of their own, it was likely that Bobbi and Archie would be moved on.

‘But it’s a rule,’ Megan said with feeling. She yawned and leaned against my leg, looking crestfallen.

I smiled. ‘You’re right, sweetie, it is.’ We’d spent most of yesterday evening at my mother’s house and, being New Year’s Eve, she hadn’t gone to bed until late. I could tell she was flagging so I quickly showed Bobbi the bathroom, pointed out where I’d be sleeping, and then opened the door to the room opposite my own.

‘Wow!’ Bobbi shouted, running in and diving face down on the sheepskin rug in the middle of the floor. We had spent yesterday afternoon filling the room with Lego and Bratz dolls, Transformers and Brio; anything we thought might appeal to children of Archie and Bobbi’s age. There was a large purple beanbag beside the bunk bed and a giant teddy next to the bookshelf in one of the alcoves. Of all the accessories, it was the furry rug that always seemed to appeal most to the children I looked after.

Archie walked slowly around the room, stopping to examine the framed pictures on the wall that I’d put up when he was referred. I wasn’t a fan of stereotyping but sports tended to be more or less a safe bet when it came to boys of Archie’s age, and several of the pictures around the top bunk were football related. ‘It’s such a cool room,’ he said, straightening one of the slightly lopsided frames. ‘Thanks, Rosie.’

I smiled at him and he made an attempt at smiling back, though his eyes once again refused to join in. My stomach contracted with pity. I was beginning to get the sense that his compliments were driven by panic, as if his survival depended on them.

‘I thought you could have the top bunk, Archie. Happy with that?’

He nodded. ‘We have bunk beds at home.’

I had dotted a few soft toys around the bottom bunk and one of them, a pink rabbit, seemed to take Bobbi’s fancy. She dived onto the mattress, grabbed it in her mouth and then rolled back onto the rug with it dangling from her jaws. ‘This is the best bedroom in the whole world!’ she declared, rolling around. I smiled, wondering what her bedroom at home was like. I looked at Archie, but his expression was unreadable.

After the tour we all sat in the living area to watch Paddington. When I say ‘sat’, Megan, Archie and I sat. Bobbi spun in circles on the rug, threw herself into kamikaze-style forward rolls and snatched every soft toy that Megan chose to sit on her lap. Every time I intervened, she asked if she could have more food.

Megan lost patience about twenty minutes into the film and began throwing herself around as well. Mungo watched the rumpus from beneath the coffee table, growling softly whenever Bobbi got too near. ‘Tell you what,’ I said, ‘let’s get you into your coats and shoes and you can have a bounce on the trampoline while I prepare dinner, okay?’ It was only two o’clock, but I had a feeling that late afternoon held the potential for trouble. I wanted to prepare something to throw in the oven so that I’d be free to deal with whatever cropped up.

I watched them through the kitchen window as I fried some mince and peeled potatoes for a cottage pie. Megan and Bobbi dived crazily around the trampoline, giggling and bumping into one another. I felt a jolt of encouragement as I watched them. Archie bounced to one side, slowing protectively whenever they veered close.

After a particularly violent collision Megan fell awkwardly and bumped her ear on one of the posts holding the safety net. She clamped a hand to the side of her head and looked mournfully towards the house. I slipped my shoes on, but by the time I’d reached the door Archie had already given her a cuddle.

About twenty minutes later she climbed, rosy cheeked, through the net and pulled Archie by the hand to the house. ‘She wants to show me how to draw a cloptikler,’ he said with a wry smile as they came into the house.

‘Oh, brilliant!’ I mouthed a thank you over the top of Megan’s head. He gave me a slow eye roll and shook his head, the sort of reaction I’d expect from someone much older. I tried to remember being nine years old. Shy and home-loving, I knew I wouldn’t have coped with such a momentous move the way Archie seemed to have done.

I realised then what Joan had meant when she said that Archie was an unknown quantity. Was it possible that he possessed enough resilience to cope with what the last few days had thrown at him, without the tiniest crack in his composure? As I stood at the sink washing up, my eyes drifted back to the trampoline at the end of the garden. Bobbi was still there but her movements had slowed. She was bouncing lethargically, without the faintest glimmer of enjoyment on her face. All alone, she looked completely bereft.

Abandoning the saucepan I was holding, I was about to go outside and talk to her when Megan shot past me, back into the garden. ‘Bobbi, we’re back!’ she yelled, running towards the trampoline with her arms in the air, jazz hands shimmying all the way. Bobbi’s expression brightened. She ran over and parted the net for Megan to pass through, and the pair stood grinning at each other.

‘Here we go again,’ Archie said, trudging past me. I laughed, but again I was struck by the sense that his words mismatched his age. It was as if he were acting a role, one he didn’t have much heart to play.

‘Archie, just a second. I thought I might sort your clothes out now. Are you happy for me to go through your suitcase? Or would you prefer to do it yourself?’

He shrugged. ‘Not really. You can do it. Not my rucksack though, I can do that.’ He went to the door but then stopped and turned. ‘Thank you, Rosie.’

A slow shiver ran across the back of my neck as I watched him walk down the path. I took to mashing the boiled potatoes, trying to shake the uncomfortable feeling away. I puzzled over my reaction. I couldn’t quite fathom why his apparent maturity should make me feel so uncomfortable.

His sister’s struggles were clear to see. Bobbi was in ‘flight’ mode, so that she literally couldn’t keep still. I told myself that, being that bit older, Archie had perhaps managed to devise better coping strategies in dealing with the stress.

At a little after half past four, when I put the cottage pie in the oven, there was still no sign of their play fizzling out. I decided to make the most of the time by sorting through their clothes to see if anything needed to be washed. When children arrive in placement I usually wash most of their clothes straight away, only holding a few items back to retain the comforting smell of their home. I carried their suitcases into the kitchen and set them down in front of the washing machine, but when I opened them up, the fresh scent of washing powder rose to greet me. Joan had washed everything. It was a lovely, welcome surprise.

I watched the children from the upstairs window as I put everything away in their room. They were still playing happily and I began to feel quietly confident that the placement would be manageable, and that everything was going to work out just fine.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/rosie-lewis/broken-a-traumatised-girl-her-troubled-brother-their-shocking/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Rosie Lewis

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Семейная психология

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Nine-year-old Archie and his five-year-old sister, Bobbi, are taken into emergency police protective custody after an incident of domestic violence at their family home.Rosie collects the children from their out-of-hours foster carer on New Year’s Day and instantly recognises Archie from a domestic violence workshop she helped with. Rosie remembers that when asked what he enjoyed most about the course, Archie said: ‘the biscuits’.Social workers are concerned that Archie and Bobbi have been neglected. As Rosie gets to know the children, she begins to suspect that something far more disturbing lies in their past.Archie, jovial and polite, bats away Rosie’s attempts to talk to him about anything serious with witty one-liners and sophisticated distractions. Bobbi reacts violently, lashing out and throwing herself around. Rosie has never seen a child as young a Bobbi behaving so viciously, but it is Archie she is most concerned about as the weeks go by.After a worrying incident at school, Archie tearfully discloses the truth – a shocking secret that has left him and his sister traumatised. Horrified at what she learns, Rosie is determined to help the young siblings find a forever-home that will provide them with the love and care they deserve.