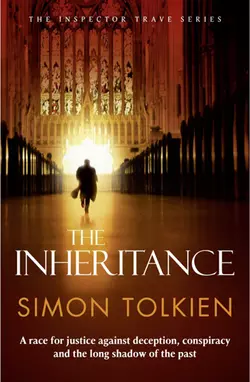

The Inheritance

Simon Tolkien

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Триллеры

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: When an eminent art historian is found dead in his study, all the evidence points to his estranged son, Stephen. With his fingerprints on the murder weapon, Stephen’s guilt seems undeniable.As the police begin to question five other people who were in the house at the time, it is revealed that Stephen’s father was involved at the end of World War II in a deadly hunt for a priceless relic in northern France, and the case begins to unravel.As Stephen’s trial unfolds at the Old Bailey, Inspector Trave of the Oxford police decides he must go to France and find out what really happened in 1944. What artefact could be so valuable it would be worth killing for? But Trave has very little time – the race is on to save Stephen from the gallows.