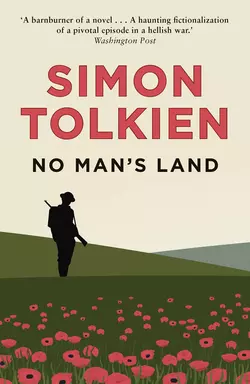

No Man’s Land

Simon Tolkien

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 791.89 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From the slums of London to the riches of an Edwardian country house; from the hot, dark seams of a Yorkshire coalmine to the exposed terrors of the trenches, Adam Raine’s journey from boy to man is set against the backdrop of a society violently entering the modern world.Adam Raine is a boy cursed by misfortune. His impoverished childhood in the slums of Islington is brought to an end by a tragedy that sends him north to Scarsdale, a hard-living coalmining town where his father finds work as a union organizer. But it isn’t long before the escalating tensions between the miners and their employer, Sir John Scarsdale, explode with terrible consequences.In the aftermath, Adam meets Miriam, the Rector’s beautiful daughter, and moves into Scarsdale Hall, an opulent paradise compared with the life he has been used to before. But he makes an enemy of Sir John’s son, Brice, who subjects him to endless petty cruelties for daring to step above his station.When love and an Oxford education beckon, Adam feels that his life is finally starting to come together – until the outbreak of war threatens to tear everything apart.