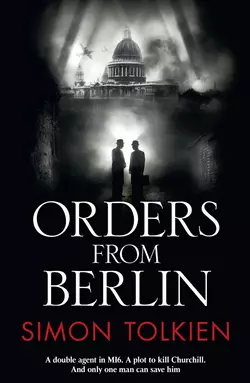

Orders from Berlin

Simon Tolkien

An ingenious thriller in which young Detective Constable Trave uncovers a sophisticated plot at the heart of MI6 to assassinate Churchill and bring the Second World War and the whole Allied effort to an untimely end.It’s 1940, and Bill Trave is a Detective Constable in his early thirties working in West London. France has fallen and the capital is being bombed both day and night – it seems against all odds that Britain can survive the onslaught. Almost single-handedly Winston Churchill maintains the country’s morale, with the German enemy convinced that his removal would win them the War.Albert Morrison, a rich widower forced into early retirement by failing eyesight, is stabbed to death in his Chelsea flat. His only daughter, Ava, tells Trave that she would read the newspapers to him every evening, and the night before his death he had become suddenly excited when she read him an obscure obituary notice.At Morrison’s funeral, Ava learns from an old colleague that her father worked for MI6 before the War. The obituary notice was a coded message preparing for an assassination, although it does not specify the target. Trave realizes that there is a Nazi double agent within MI6, with a plan to assassinate Churchill and to set up another agent to take the blame. He is in a race against time to save Churchill, for if he fails, Britain’s entire war effort could be at stake…

SIMON TOLKIEN

Orders from Berlin

For my father and for my son

CONTENTS

Title Page (#u004574a8-57a2-588a-8e76-1898e46eb166)

Dedication (#u53eb5e5b-7b60-5552-8e02-204d8c5f8d08)

September 1940: In High Places (#u11a06851-2190-5a1f-8d86-e1ce9b56179b)

Chapter I (#ua1df811e-4c3c-5d14-a368-2064fb8e0c35)

Chapter II (#ua0caa019-69e2-5aa8-b5e3-38e134a24428)

Chapter III (#uc249ab8e-41e1-5054-8209-37ac825b4770)

Chapter IV (#ubcddcb43-313f-5a12-8ee0-9720b0d3a24a)

Part One: Murder (#u9a4a3f94-83ad-5efe-9f31-603818a7b0a5)

Chapter 1 (#ubb48722e-8560-5014-b17e-d4a74bd6e370)

Chapter 2 (#ubf600878-7352-540e-880f-3baf6ad8f729)

Chapter 3 (#u6892c934-0345-5919-bab3-b5ba3f8d6fc8)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Berlin (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: Assassination (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Berchtesgaden (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

SEPTEMBER 1940 (#ulink_152d7537-a39b-5648-b545-db51c628bd01)

I (#ulink_9f73b100-0bd8-5e99-bf6e-97209a548dce)

Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Gestapo and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the intelligence division of the SS, stood to one side, a few yards away from the group of generals and admirals gathered around Adolf Hitler. An unfamiliar figure in his eyeglasses, the Führer was standing, looking down at a large map of Europe spread out across an enormous Teutonic oak table that had been moved for the purpose of the meeting into the centre of the main hall of the Berghof, Hitler’s summer residence high in the Bavarian Alps. One by one, the military leaders took turns to brief their commander-in-chief on the state of preparation for Operation Sea Lion, the high command’s code name for the invasion of England. It was due to be launched any day now according to timetables that had been agreed upon at previous conferences held during the summer either here or at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.

The line of the sharp late-summer sunlight coming in through the panoramic picture window at the back of the hall lit up the group around the table but left Heydrich a man apart, lurking in the shadows. He hadn’t been called on to speak yet, and he knew that this was unlikely to happen while the meeting remained concerned solely with issues of invasion strategy. He was here not as a soldier, but because it was his responsibility to plan and organize the control measures that would need to be taken against resistance groups and other undesirables once the panzer divisions had seized control of London, and he had already identified a suitably ruthless SS commander to take charge of the six Einsatzgruppen cleansing squads assigned to carry out the first wave of arrests and deportations. A special list of high-value targets assembled on Heydrich’s orders contained 2,820 names ranging from Winston Churchill to Noël Coward and H. G. Wells.

This was a military conference, so other than Heydrich and the Führer and Hermann Goering – here by virtue of his command of the Luftwaffe – there were no party men present. Heydrich’s thin upper lip curled in a characteristic expression of contempt as he watched the debate unfold. He hated these army and navy grandees bedecked in their medals and gold braid, and he sensed that the Führer did, too. They were careerists, men who had climbed the ladders of promotion in the inter-war years, drawing their state-guaranteed pay at the end of every month, playing war games in their barracks, and toasting the Kaiser, while true National Socialists like Heydrich had fought behind their Führer in the streets, prepared to die for the cause in which they all believed.

But there was another reason for Heydrich’s antipathy. Once upon a time, he too had been an officer with good prospects, an ensign on the battleship Schleswig-Holstein, until he had been summarily dismissed for conduct unbecoming an officer back in 1931. A woman he’d spurned when he’d met another he preferred had turned out to be a shipbuilder’s daughter who complained to her father, and Heydrich had paid the price. Admiral Raeder had taken away his honour with a stroke of a pen: the same Raeder who was now standing ten paces away from Heydrich, briefing Hitler on the naval preparations for the invasion. Every time he saw the admiral, Heydrich felt the injustice and humiliation flame up inside him again like a festering wound that would never heal. He fully intended to get even with Raeder, but not yet. The time wasn’t right. Heydrich was good at waiting. As the English said, vengeance was a dish best served cold.

Heydrich had no doubt that Raeder remembered. Not only that – he was sure that the admiral regretted his decision. It probably kept him up at night worrying. Everyone in this room knew Heydrich’s reputation. He’d observed the way they had all kept him at a distance when they first came in, throwing him uneasy sideways glances as they’d milled about the hall before the meeting began, drinking coffee from delicate eighteenth-century Dresden cups, until Hitler entered through a side door on the stroke of two o’clock and they all came to attention, raising their arms in salute.

Heydrich knew the names these men of power and influence called him behind his back – ‘blond beast’; ‘hangman’; ‘the man with the iron heart’. He knew how much they feared him, and with good reason. Back in Berlin, under lock and key at Gestapo headquarters, he had thick files on each and every one of them, recording every detail of their private lives in an ever-expanding archive of cross-referenced, colour-coded index cards that he had worked tirelessly to assemble over the previous nine years.

Some of them he’d even enticed into the high-class whorehouse he’d established on Giesebrechtstrasse with two-way mirrors and hidden microphones embedded in the walls. Within moments on any given day, he could summon to his desk photographs and sworn statements, letters, and even transcribed tape recordings of them spilling their sordid secrets to the girls he had had specially recruited for the task. Facts and falsehoods, truth and lies – it didn’t matter to Heydrich so long as the information could be of use in controlling people, forcing them by any means available to do his and the Führer’s will.

Heydrich smiled, thinking how one word from him in Hitler’s ear and the highest and mightiest of these strutting commanders in their glittering uniforms could find themselves down on their hands and knees, naked, manacled to a damp concrete wall in the cellar prison located in the basement underneath his office at 8 Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse. It amused him to have his victims cowering and screaming so close to where he worked, seated behind his magnificent nineteenth-century mahogany desk with an elaborately framed photograph of the Führer staring down at him from the oak-panelled wall opposite, ready to provide him with inspiration whenever he looked up from the stream of documents that required his constant attention every day.

From the outset, when he first joined the party back in 1931, Heydrich had felt a sense of kinship with Hitler that he had never experienced with anyone else he’d met before or since. And for several years now he had sensed that the Führer felt it too. Once, closeted together in the Führer’s apartment on the upper floor of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, where Heydrich had gone to brief Hitler in the aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom two years earlier, the Führer had held up his hand for silence and looked Heydrich in the eye. It was only for a moment or two, but it felt to Heydrich as if he were back in the church at Halle where he had grown up, with the Catholic priest examining his soul. As a child he had turned away ashamed, but as a man he had met Hitler’s gaze and felt as though the Führer were looking inside him, turning him inside out, searching for the truth of who he really was. And then, after a moment or two, Hitler had nodded as if pleased with what he’d seen.

‘We will go far together, you and I,’ the Führer had said – Heydrich remembered his exact words – ‘because you are a true believer, and because, like me, you have the will. The will is everything, Reinhard. You know that, don’t you?’

Afterwards they had carried on talking about round-ups and press releases and other administrative measures against the vermin Jews, but the moment had stayed with Heydrich, vividly engraved on his memory as a life-changing moment. He admitted it to no one, but secretly he thought of himself as Hitler’s heir and the Third Reich, vast in size and purified in blood, as his own personal inheritance.

Nowadays he looked forward to meetings with Hitler almost like a lover awaiting his next tryst, and when he was in the Führer’s presence he watched him intently, as if he were storing up every impression of his master in the filing cabinet of his mind, packing each one carefully away for later scrutiny when he was alone, back in Berlin. There was a power, a certainty, in Hitler that drew Heydrich like a magnet. It always had, even in the early days when the National Socialist faithful had been so few, meeting in the back of smoke-filled beer cellars and conspiring together in the watches of the night, dreaming the impossible – Heydrich had known from the outset that Hitler was the one who could make the impossible come true.

But today the Führer seemed unlike himself for some reason. He was uncharacteristically silent, allowing the debate between the Wehrmacht commanders to carry on unchecked. Backwards and forwards, reproach and counter-reproach, the argument growing more heated by the minute. It was as if he were unsure of what to do, uncertain of his next move. To Heydrich it felt as if they were on a ship in a storm, keeling from side to side while the rudder stood unattended, crashing around with the buffeting of the waves.

‘The weather conditions in the English Channel are extremely variable,’ said Raeder mournfully. He sounded just like some miserable provincial schoolmaster reading from an instruction manual, thought Heydrich, and a Cassandra too – everything he said seemed negative, designed to undermine the invasion plan. ‘And we lack specialized landing craft,’ Raeder continued. ‘Instead we are relying on converted river barges and ferryboats. Many of these are unpowered and can only be used in calm seas. They will make easy targets for the enemy. And there are also problems with transporting the heavy armour. We are working on making our tanks submersible, but we need more time. It is not the same as when we attacked Norway. We sustained heavy losses in that campaign, and this time the British know we are coming. They will use their navy against the beachheads even if we are able to establish them. And that is a big if—’

‘I have said it before. The invasion front is too narrow,’ interrupted Halder, chief of the army general staff, who had been shifting from one foot to another with growing impatience as Raeder talked. An old-school Prussian officer, he spoke in a clipped, angry voice, jabbing his finger down on the part of the map that showed the south-east coast of England. ‘One hundred miles is not enough even with paratroops landing in support. We might just as well put Army Group A through a sausage machine.’

‘Yes, yes, I have heard this before,’ said Hitler, showing undisguised irritation as he stepped back from the table. ‘More men; more armour; more boats. But it is air supremacy that we need – and before the autumn gales make a Channel crossing impossible. You promised me this,’ he said, wheeling round to face Goering, who was standing on his right. ‘And yet the enemy is shooting down our planes every day, hunting down our bombers like dogs. Tell me the truth, Herr Reichsmarschall. No gloss; no varnish. Can you control the skies or not?’

Everyone turned to look at Goering. He was a natural focus of attention, as he was far and away the most distinctive figure in the room. His flamboyant uniform marked him out from everyone else, which was in fact just what he intended. Rumour had it that Goering changed his uniform five times a day, and his choice for this meeting was garish even by his usual standards. It was one of several bright white outfits that he’d designed for himself, replete with multicoloured crosses and decorations. Some of the larger medals he’d awarded to himself, and Heydrich knew from his army of spies that Goering’s appearance in this costume on cinema newsreels was an object of popular ridicule throughout the country, as no one could understand how he kept his uniforms so white when most of the population couldn’t get enough soap to keep their clothes even passably clean. Goering’s vanity was as boundless as his appetite, dwarfed only by his gargantuan self-belief.

‘It is only a matter of time,’ he said, standing with his arms akimbo, inflated with his own importance. ‘London is burning. The population is cowering in makeshift shelters … the docks are half-destroyed—’

‘To hell with the docks,’ Hitler interrupted angrily. ‘The skies are what matters. You heard my question. Can you break the English air force; can you destroy them like you promised?’

‘Yes. Operation Eagle is succeeding,’ said Goering, responding immediately in a quieter voice. His acute sensitivity to Hitler’s changing moods had stood him in good stead over the years, and he had gauged correctly that a measured assessment of the Luftwaffe’s capabilities, free of hyperbole, was what was now required. ‘It is a matter of simple mathematics,’ he said. ‘Our attacks on British factories and airfields have massively reduced their capacity to keep pace with the severe losses that they are continuing to sustain every day. They are running out of planes and they are running out of pilots. Any day now their fighter command will have to withdraw from southern England and our landings can begin. Their weakness is shown by the damage we have already been able to inflict on London. They would never have allowed it if they could have prevented it.’

Hitler stared balefully at Goering for a moment, as if trying to assess whether his subordinate’s confidence was an act put on for his master’s benefit, but Goering met the Führer’s gaze full on without dropping his eyes.

‘We shall see,’ said Hitler, taking off his glasses. ‘We shall soon see if your assessment is correct, Herr Reichsmarschall.’

It was a signal that the conference was over. One by one, the military commanders saluted Hitler and left the hall. Heydrich moved to follow them, but Hitler held up his hand.

‘Stay,’ he said. ‘There is something I need to talk to you about. We can go out on the terrace. The fresh air will do us good.’

It was one of the last days of summer. The green-and-white umbrella canopies moved gently in the slight breeze above the white chairs and tables, and the bright afternoon sun threw shadows across the wide terrace and glittered in the windows of the Berghof. Across the tops of the pine trees down in the valley, the snow-capped mountains of Austria reared up under a cloudless blue sky. Who would have guessed, thought Heydrich, that hidden not far away from where they were standing, a battery of smoke-generating machines stood ready to drown the Berghof in a blanket of thick white fog should it come under threat from enemy bombers.

The war seemed very far away in the silence. The sound of his and Hitler’s footsteps echoed on the flagstones as they walked over towards the parapet.

‘We can talk here,’ said Hitler, sitting down at one of the tables and motioning Heydrich to the chair opposite. Hitler sighed, stretching out his legs, and then rubbed his knuckles in his eyes. Perhaps gazing at the map during the briefing had given him eye strain, or perhaps it was something more profound. Whatever the cause, the Führer had certainly seemed out of sorts at the conference.

‘I don’t like it,’ said Hitler, shaking his head. He had his hands folded in his lap now, but he was gently clasping them together – a sure sign of inner turmoil. ‘This is not what I wanted. This is not the war we should be fighting.’

‘Against England?’

‘Yes,’ said Hitler, bringing his hands together suddenly and holding them tight. His bright blue eyes were blazing with the intensity of his feeling. ‘They are not our enemy, and yet they will not listen to reason. It’s that fool Churchill. He has possessed them with his talk of blood and sacrifice. Don’t they understand that we have no quarrel with them? They can keep their empire. I want them to. It’s a noble institution. I have told them that again and again, but they will not listen.’

Hitler had begun to shout, but now he stopped suddenly. It was as though an electric motor had been suddenly turned off, and Heydrich tensed, waiting for the power to resume. But Hitler continued after a moment in a quiet voice, visibly holding himself in check.

‘I don’t want this invasion. I am fully prepared to spend German blood to get this great country what it needs, but that is in the east,’ he said, pointing with his forefinger out towards the mountains facing them across the valley. ‘We must defeat Bolshevism and take the land west of the Urals for our people. That is our destiny, but to lose an army trying to conquer Brighton or Worthing or Eastbourne … that is intolerable.

‘Unerträglich!’ Hitler spat out the word. It seemed once more as if rage were going to get the better of him, but again he pulled himself back from the brink. ‘The war in the west is a means to an end,’ he said slowly, choosing his words carefully. ‘The object is to ensure that we are not stabbed in the back when we begin the war that matters, the one against Russia. And that must be soon, Reinhard … soon. We cannot wait much longer. Stalin is rearming; the Soviets are expanding – they are like ants; they come up out of the soil and multiply, and soon we will not be able to destroy them. Not if we wait.’

‘Yes,’ said Heydrich, inspired by the Führer’s vision. ‘As always, you are right.’

‘And so we need peace with the English, not war,’ Hitler went on after a moment. ‘But how do we achieve this? Not with an invasion. Not unless we have to, and even then I am reluctant. Raeder is an old woman, but he is right about the difficulties that we face with the crossing. You cannot rely on the weather. The Spanish tried 350 years ago and their ships were wrecked. Napoleon could not even make it across the Channel. Our landing craft are second-rate and we don’t have the naval superiority we need to protect them.’

‘But if we win in the air,’ said Heydrich, ‘perhaps that will make the difference. The Reichsmarschall said that it is only a matter of time—’

‘Time that we do not have,’ said Hitler, interrupting. ‘I will believe Goering when the English air force stops bombing Germany. For now we need to try something else. And that is where you come in, Reinhard.’

Heydrich came alert. He’d been absorbed by the discussion of grand strategy and had forgotten for a moment that the Führer had had him wait behind after the conference for a purpose.

‘What can I do?’ he asked eagerly.

Hitler held a finger to his lips in a warning gesture. A pretty serving girl wearing a Bavarian peasant dress had appeared behind Heydrich with a tray of peppermint tea. She set the cups on the table and curtsied to the Führer, who smiled affably in response.

‘Tell me about Agent D. Is he continuing to be reliable?’ asked Hitler, sipping from his cup. He seemed serene now, and there was no trace of the anger and frustration that had been in evidence before the tea arrived. It was as if he were introducing a subject of minor interest into the conversation.

‘Yes,’ said Heydrich without hesitation. ‘He is one of the best agents I have ever had. I trust him implicitly.’

‘Good. And his intelligence – is it useful?’

‘He is doing well. As agreed, he provides disinformation where it cannot be detected as false and true intelligence where it does not threaten our security and can be verified by the enemy. His masters in the British Secret Service are pleased with him – he has recently been promoted to a level where he is present at some MI6 strategy meetings, and his reports are read by their Joint Intelligence Committee. Soon, if we are patient, he should have access to the most top-secret information.’

‘Excellent,’ said Hitler, rubbing his hands. ‘As always, your work does you credit, Reinhard. You make the Abwehr look like circus clowns.’

Heydrich bowed his head, savouring the compliment. There was nothing he would have liked better than to further extend his Gestapo empire into the field of foreign intelligence, where he was currently forced to compete not only with the Abwehr, the traditional Secret Service headed by Admiral Canaris, but also with Ribbentrop’s equally second-rate Foreign Office outfit.

‘But I am afraid that we are going to have to be a little less patient,’ Hitler went on smoothly. ‘Agent D gives us an opportunity not just to make the British believe that we are serious about the invasion, but also to make them think that we can succeed. That is what is missing now. Churchill still thinks he can win. If he receives information that makes him stop believing that, then he will have to negotiate. He will have no choice. Do you understand me, Reinhard?’

‘Yes, of course. But if they find out that what D is telling them is untrue, then his cover will be blown. He is an important asset—’

‘And will remain so,’ said Hitler, holding up his hand to forestall further objection. ‘If D’s cover is blown, then Churchill won’t believe the information he’s being given and our scheme fails. No, we must exaggerate our strength on the sea and in the air, but not to the point where it strains credibility. It’s a delicate balance – a task requiring a sure hand. Can I rely on you, Reinhard? Can you do this for me?’

‘Yes. I am in your hands. You know that. But I will need authority to obtain details of our capability from the service chiefs and advice on the level to which it can be distorted without arousing suspicion.’

‘Here. This should be sufficient,’ said Hitler, taking a folded document from his pocket and handing it across the table. ‘Now, tell me about D’s source for his information. What do the British believe the source’s position is at present?’

‘On the general staff, attached to General Halder.’

‘I see,’ said Hitler, licking his lips meditatively. ‘Well, I think we are going to have to award him an increase in status if the British are going to believe that he’s able to provide D with information of the value that I have in mind. What do you suggest, Reinhard?’

‘Aide-de-camp?’

‘Yes, very good – that sounds just right,’ said Hitler, looking pleased. ‘Sufficient status to give him access to top-level military conferences like the one today, and to make it credible that he’s heard me speak of both my willingness to invade and my desire for peace. We can downgrade the source’s status later if it becomes too conspicuous for a fictional character,’ Hitler added with a smile.

‘All as you say – it will be done,’ said Heydrich, getting up from the table and putting on his SS cap, which he had held balanced on his knees during the conversation. He was about to salute, but Hitler forestalled him.

‘Remind me – what is your usual method for communicating with D?’ he asked.

‘We have a reliable contact in the Portuguese embassy in London. Information and reports are sent through the diplomatic bag to Lisbon and then brought on to Berlin from there, and the same in the other direction. It takes time, but it is safe and efficient.’

‘And radio?’

‘The codes we have work for short messages. But not for anything longer – D does not have an Enigma machine and so a report or a briefing instruction like this one wouldn’t be secure. There is a drop we can use that D knows about.’

‘A drop?’

‘Yes. On the coast of Norfolk, north-east of London. We have a sleeper agent there who will pick up documents that we drop from a plane. It works. I have used it before, but D would have to go there to collect.’

‘Very well. Use the drop. Time is of the essence. Everyone needs to understand that. If we wait too long, the weather will turn against us and Churchill will know we are not coming. So you must give this task top priority – put aside everything else that you are working on until the briefing document is ready for me to look at. And when it is, bring it here in person, and then, if I approve, you can send it.’

Hitler nodded and Heydrich raised his right arm in salute and turned away. At the top of the steps leading down to the road, he looked back at the Führer, who was now leaning back in his chair with his hat tipped down over his eyes and his legs stretched out in front of him. He looked like a holidaymaker, Heydrich thought, enjoying the last of the day’s sunshine with a cup of afternoon tea at his side. A neutral observer would have laughed at the suggestion that this was the most powerful man in Europe, who held the fate of nations balanced in the palm of his hand.

II (#ulink_c0229146-ec69-535d-951e-2a97e30b0f36)

A flight of geese rose up in a sudden rush from the island in the lake, beat the air above the ruined bird-keeper’s cottage, and then soared into the London sky towards the white vapour trails of the fighter aircraft that had been engaged in aerial battles above the city for most of the day.

Seaforth stopped to look, but Thorn paid no attention, continuing his angry march down Birdcage Walk with his hands thrust deep inside his trouser pockets. Ever since he first came to London, Seaforth had loved St James’s Park, and he felt profoundly grateful that he now worked so close to it that he could come here almost every day, sit under the ancient horse-chestnut trees, and look up past the falling boughs of the weeping willows to where the buildings of Whitehall rose from out of the water like the palaces of a fairy kingdom. But today there was no time to dawdle. Churchill was waiting for them in his bunker, and Seaforth turned away from the view and walked quickly to catch up with his companion.

He felt intensely alive. In the morning and again in the afternoon, he’d left his desk and gone out and joined the crowds in the street outside, gazing up at the aerial dogfights going on above their heads – Hurricanes and Spitfires and Messerschmitts wheeling and twisting through crisscrossing vapour trails, searching for angles of attack. The noise had been tremendous – the roar of the machine guns mixed up with the exploding anti-aircraft shells; the underlying drone of the aeroplanes; the shrapnel falling like pattering rain on the ground; bombs exploding. Several times he’d watched transfixed as planes caught fire and tumbled from the sky, with black smoke pouring out behind them as they fell. A Dornier bomber had hit the ground a few streets away, exploding in a column of crimson-and-yellow flame, and Seaforth could still hear the people around him cheering, throwing their hats up into the air while the German crew burned. Some bombs had fallen close by – there was a rumour that Buckingham Palace had been hit – but Seaforth had been too absorbed in the battle to worry about his personal safety. He’d felt he was watching history unfold right above his head.

And then at the end of the day he had been caught up in the drama when the unexpected summons had come from the prime minister’s office and he and Thorn had set off together through the park. Now the day’s fighting seemed to be over – there was no more sign of the enemy, only a few British fighters patrolling overhead, although Seaforth knew that the bombers would almost certainly return after dark to rain down more terror on the city’s population. Seaforth wondered about the outcome of the day’s battle. He’d tried to talk to Thorn about it, but Thorn had shown no interest in conversation.

Seaforth didn’t like Thorn; he didn’t like him at all. He objected to the disdainful, upper-class voice in which Thorn spoke to him, treating him like a member of some inferior species. He rebelled against having to answer to a man for whom he had no respect. He tipped his felt hat back at a rakish angle and amused himself with trying to annoy Thorn into talking to him.

‘Is it true what they say, that Churchill receives visitors in his bath?’ he asked. ‘I hope he doesn’t do that with us. I think I’d find it hard to concentrate. Wouldn’t you?’

Thorn grunted and stopped to light a cigarette, cupping the lighted match in his hand to protect it from the wind.

‘You hear so many strange things,’ Seaforth went on, undaunted by his companion’s lack of response. ‘Like how he takes so many risks, going up on the roof of Downing Street to watch the bombs and the dogfights – as if he’s convinced that nothing will ever happen to him, like he’s got some kind of divine protection; a contract with the Almighty.’

‘Why are you so interested in where he goes?’ Thorn asked sharply.

‘I’m not. I’m just trying to make conversation,’ said Seaforth amicably.

‘Well, don’t.’

‘Whatever you say, old man,’ said Seaforth, shrugging. He whistled a few bars of a patriotic song and then went back on the attack, taking a perverse pleasure in Thorn’s growing irritation.

‘How many times have you seen the PM? Before now, I mean?’ he asked.

‘Two or three. I don’t know,’ said Thorn. ‘Does it matter?’

‘I’m just trying to get an idea of what to expect, that’s all. Where did you go – to Number 10 or this underground place?’

‘You ask too many damn questions,’ said Thorn, putting an end to the conversation. He took a long drag on his cigarette, inhaling the smoke deep into his lungs. He was trying not to think about Seaforth or the forthcoming interview with the Prime Minister, and the effort was making his head ache.

He was eaten up with a mass of competing thoughts and emotions, and he felt too tired to work out where genuine distrust of Seaforth ended and his own selfish resentment of the young upstart began. Churchill’s summons to the two of them had placed him in an impossible position. His inclusion was recognition that he was the one in charge of German intelligence, but Thorn knew perfectly well that it was Seaforth Churchill wanted to talk to. It was Seaforth’s report that the Prime Minister wanted to discuss; it was Seaforth’s high-value agent in Germany he was interested in. Thorn was no better than a redundant extra at their meeting.

They reached Horse Guards and climbed the steps to 2 Storey’s Gate. Thorn felt a renewed surge of irritation as he sensed Seaforth’s growing excitement. They showed their special day-passes to a blue-uniformed Royal Marine standing with a fixed bayonet at the entrance and went down the steep spiral staircase leading to the bunker. Through a great iron door and past several more sentries, they came to a corridor leading into the labyrinth. Seaforth blinked in the bright artificial light and greedily took in his surroundings – whitewashed brick walls and big red steel girders supporting the ceilings. It was like being inside the bowels of a ship, Seaforth thought. The air was stale, almost fetid, despite the continuous hum of the ubiquitous ventilation fans pumping in filtered air from outside, and there was an atmosphere of concentrated activity all around them. Through the open doors of the rooms that they passed, Seaforth saw secretaries typing and men talking animatedly into telephones – some in uniform, some in suits. People hurried by in both directions, and Seaforth was struck by the paleness of their faces, caused no doubt by a prolonged deprivation of light and fresh air. Tellingly, a notice on the wall described the day’s weather conditions, as if this were the only way the inhabitants of this God-forsaken underworld would ever know whether the sun was shining or rain was falling in the world above.

They stopped outside the open door of the Map Room. This was the nerve centre of the bunker, where information about the war was continually being received, collated, and distributed. Two parallel lines of desks ran down the centre of the room, divided from each other by a bank of different-coloured telephones – green, white, ivory, and red – the so-called beauty chorus. They didn’t ring but instead flashed continuously, answered by officers in uniform sitting at the desks. Over on a blackboard in the corner, the day’s ‘score’ was marked up in chalk – Luftwaffe on the left with fifty-three down and RAF on the right with twenty-two. It was a significant number of ‘kills’ but fewer than Seaforth had anticipated, judging from the mayhem he’d witnessed in the skies over London during the day.

Seaforth’s eyes watered. The thick fug of cigarette smoke blown about by the electric fans on the wall made him feel sick, but he swallowed the bile rising in his throat, determined to see everything and to try to understand everything he saw. No detail escaped his notice – the codebooks and documents littering the desks lit up by the green reading lamps; the map of the Atlantic on the far wall with different-coloured pins showing the up-to-date location of the convoys crossing to and from America; the stand of locked-up Lee-Enfield rifles just inside the entrance to the room.

‘What are you looking at?’ asked a hostile voice close to his ear. It was Thorn. Seaforth had been so absorbed in his observation of the Map Room that he had momentarily forgotten his companion. But Thorn had clearly not forgotten him. He was staring at Seaforth, his eyes alive with suspicion.

‘Everything,’ said Seaforth. ‘This is the heart of the operation. Of course I’m curious.’

‘Curiosity killed the cat,’ said Thorn acidly.

‘Mr Thorn, Mr Seaforth. If I could just see your passes?’ A man in a dark suit had appeared as if from nowhere. ‘Good. Thank you. If you’d like to come this way. The Prime Minister will see you now.’

They passed through an ante-room, turned to their left, and suddenly found themselves in the presence of Winston Churchill, dressed not in a bathrobe but in an expensive double-breasted pinstripe suit with a gold watch chain stretched across his capacious stomach. He was wearing his trademark polka-dot bow tie and a spotless white handkerchief folded into a precise triangle in his top pocket. It was the Churchill that was familiar from countless Pathé newsreels and photographs, except for the stovepipe hat, and that was hanging on a stand in the corner. Without the hat he seemed older – the wispy strands of hair on his head and the pudginess of his face made him seem more a vulnerable, careworn old man than the indomitable British bulldog of popular imagination.

He got up from behind his kneehole desk just as they came in, depositing a half-smoked Havana cigar in a large ashtray that contained the butts of two more.

‘Hello, Alec,’ he said, shaking Thorn’s hand. ‘Good of you to come – sorry about the short notice. And this must be the resourceful Mr Seaforth,’ he went on, fixing a look of penetrating enquiry on Thorn’s companion, who had hung back as they’d entered the room, as if overcome by an uncharacteristic shyness now that he was about to meet the most famous Englishman of his generation.

Eagerness and then timidity: Thorn was puzzled by the sudden change in Seaforth, who seemed momentarily reluctant to go forward and shake Churchill’s outstretched hand. And then, when he did so, Thorn could have sworn that Seaforth grimaced as if in revulsion at the physical contact. But Churchill didn’t seem to notice, and Thorn realized that it could well be the cigar smoke that was causing Seaforth discomfort. He was well aware how much Seaforth hated tobacco, and the sight of his subordinate’s nauseated expression had been the only redeeming feature for Thorn of Seaforth’s recent inclusion at strategy meetings in the smoke-filled conference room back at HQ.

‘I don’t need you, Thompson,’ said Churchill. For a moment, Thorn had no idea whom the Prime Minister was talking to, until he turned to his right and realized that another man was present in the room. It was Walter Thompson, Churchill’s personal bodyguard, sitting like a waxwork in the corner, tall and ramrod straight. Without a word, Thompson went out and closed the door behind him.

‘Drink?’ asked Churchill, crossing to a side table and mixing himself a generous whisky and soda. ‘By God, I need one. I hate being down here with the rest of the trogs, but Thompson and the rest of them insist on it when the bombing gets bad, so I don’t suppose I’ve got too much choice. I’d much prefer to have been up topside watching the battle. Seems like Goering’s thrown everything he’s got at us today, but the brass tell me we’ve weathered the storm so far, at least. You know, I don’t think I’ve been as proud of anyone as I’ve been of our pilots these last few weeks. Tested in the fiery furnace day after day, night after night, and each time they come out ready for action. Extraordinary!’

Churchill looked up, holding out the whisky bottle. Thorn accepted the offer, but Seaforth declined.

‘Not a teetotaller, are you?’ asked Churchill, eyeing Seaforth with a look of distrust.

‘No, sir,’ said Seaforth. ‘I just want to have all my wits about me, that’s all. I’m expecting some difficult questions.’

‘Are you now?’ said Churchill, raising his eyebrows quizzically as he resumed his seat and waved his visitors to chairs on the other side of the desk. ‘Well, it was certainly an interesting report you sent in,’ he observed, putting on his round-rimmed black reading glasses and examining a document that he’d extracted from a buff-coloured box perched precariously on the corner of the desk. ‘Lots of nuts-and-bolts information, which I like, but most of it saying how well prepared Herr Hitler is for his cross-Channel excursion, which I like rather less. We knew about the heavy build-up of artillery and troops in the Pas-de-Calais, of course, but the number of tanks they’ve converted to amphibious use is an unpleasant surprise, and we’d assumed up to now that most of their landing craft were going to be unpowered.’

‘They’ve installed BMW aircraft engines on the barges,’ said Seaforth. ‘They seem to work, apparently.’

‘So I see. Five hundred tanks converted to amphibious use,’ said Churchill, reading from the document. ‘It’s a large number if they can get them across, but that’ll depend on the weather, of course, and who’s in control of the air, and we seem to be holding our own in that department, at least for now, at any rate.’

‘There are the figures for Luftwaffe air production in the report as well – on the last page,’ said Seaforth, leaning forward, pointing with his finger.

‘Yes,’ said Churchill. ‘Again far higher than we expected. But to be taken with a pinch of salt, I think. Goering would be likely to exaggerate the numbers for his master’s benefit.’ He put down the report, looking at Seaforth over the tops of his glasses as if trying to get the measure of him. ‘Your agent’s report is basically a summary of what was discussed at the last Berghof conference, with a few opinions of his own thrown in for good measure. Is that a fair description, Mr Seaforth?’

‘He’s verified the facts where he can,’ said Seaforth.

‘But he’s an army man working for General Halder, who’s another army man,’ said Churchill. ‘He’s not going to have inside information about the Luftwaffe.’

‘He knows one hell of a lot for an ADC, and a recently promoted one at that,’ Thorn observed sourly. It was his first intervention in the conversation.

‘Too good to be true? Is that what you’re saying, Alec?’ asked Churchill, looking at Thorn with interest.

‘Too right I am. The source material was nothing like this before. Now it’s the Führer this, the Führer that. It’s like we’re sitting round a table with Hitler, listening to him tell us about his war aims.’

‘My agent didn’t have access before to Führer conferences,’ Seaforth said obdurately. ‘Now he does.’

‘Why’s he helping us?’ asked Churchill. ‘Tell me that.’

‘Because he hates Hitler,’ said Seaforth. ‘A lot of the general staff do. And he has Jewish relatives – he’s angry about what’s happening over there.’

‘How well do you know this agent of yours?’

‘I recruited him personally when I was in Berlin before the war. He felt the same way then – he loved his country but hated where it was going. I have complete confidence in him.’

‘As do his superiors, judging from his recent promotion,’ observed Churchill caustically. He was silent for a moment, scratching his chin, looking long and hard at the two intelligence officers as if he were about to make a wager and were considering which one of them to place his money on. ‘Betrayal is something I’ve always found hard to understand – even when it’s an act committed for the best of motives,’ he said finally. ‘It’s outside my field of expertise. But we certainly cannot afford to look a gift horse in the mouth, even if we do choose to regard the animal with some healthy scepticism. So, let us assume for a moment that what your agent says is true and that Hitler is ready and determined to come and pay us a visit once he’s got all his forces assembled—’

‘He thinks Hitler doesn’t want to,’ said Seaforth, interrupting.

‘Thinks!’ Thorn repeated scornfully.

‘Hitler said as much at the conference,’ said Seaforth, leaning forward eagerly. ‘He wants to negotiate—’

‘A generous peace based broadly on the status quo,’ said Churchill, finishing Seaforth’s sentence by quoting verbatim from the report. ‘And that may well be exactly what he does want,’ he observed equably, picking up his smouldering cigar and leaning back in his chair. ‘The Führer thinks he is very cunning, but at bottom the way his mind works is very simple. He’s a racist – he wants to fight Slavs, not Anglo-Saxons. But the point is it doesn’t matter what he wants. We cannot negotiate with the Nazis however many Messerschmitts and submersible tanks they may have lined up against us. Do you remember what I called them when I became Prime Minister four months ago – “a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime”?’ Churchill had the gift of an actor – his voice changed, becoming grave and solemn as he recited the line from his speech. But then he smiled, taking another draw on his cigar. ‘Grand words, I know, but the truth. We must defeat Hitler or die in the attempt. There is no hope for any of us otherwise. And so the strength of his invasion force and his wish for peace cannot change our course.’

Abruptly the Prime Minister got to his feet. Thorn nodded his approval of Churchill’s policy, but Seaforth looked as though he had more to say. He opened his mouth to speak, then changed his mind.

‘Thank you, gentlemen. Reports like this one are invaluable,’ said Churchill, tapping the document on his desk. ‘If you get more intelligence like this, I shall want to see you again straight away. Both of you, mind you – I like to hear both points of view. And you can call my private secretary to set up the appointment so we don’t have delays going through the Joint Intelligence Committee – he’ll give you the number outside. My predecessors made a serious mistake in my opinion keeping the Secret Service at arm’s length. It takes a war, I suppose, to inject some sense into government.

‘Goodbye, Alec. Goodbye, Mr Seaforth,’ he said affably, shaking their hands across the desk. ‘Seaforth – an interesting name and not one I’ve heard before,’ he said pensively. ‘Sounds a bit like Steerforth – the seducer of that poor girl in David Copperfield. Came to a bad end, as I recall. A great writer, Dickens, but inclined to be sentimental, which is something we can’t afford to be at present. The stakes are too high; much too high for that.’

III (#ulink_a4a794b6-eb4c-58a0-af93-d6360652ddfd)

Exactly the same people were present in the great hall of the Berghof as the week before; the same map of Europe was spread out across the table; and Reichsmarschall Goering was wearing the same brighter-than-white uniform with gold epaulettes and buttons and black Iron Cross medals dangling at his throat. He jabbed exultantly at the towns of south-east England with his fat forefinger and listed the damage that the Luftwaffe had inflicted upon them since the last conference. He seemed oblivious to the tight-lipped frigidity of the Führer, standing beside him.

Head of an air force and he can’t even fit inside an aeroplane. Heydrich smiled for a moment, his thin, pale lips wrinkling in contemptuous amusement at the thought of Goering trying to fit his great bulk inside the narrow cockpit of a Heinkel twin-engined bomber. Once upon a time, Goering had flown, of course – in the last war he had been a fighter ace, the last commander of von Richthofen’s Flying Circus after the Red Baron was killed in action in 1918. But now he was past it, over the hill; unfit for anything useful except to go back home to Carinhall, the ugly, tasteless mansion he’d built for himself in the Schorfheide forest north-east of Berlin and fill his belly full of rich French food while he feasted his bulbous eyes on the old master paintings he’d looted out of Paris when it fell.

Heydrich could fly. He hadn’t needed to. He could have stayed behind his desk in Berlin when the war broke out, issuing orders and decrees like other ministers. But instead he’d overcome his fears and learnt because he knew that flying would make him a god, turning in silver arcs through the clouds; insulated by silk and fur against the bitter, outlandish cold; pitting his wits and nerves against an unknown enemy until death took one or the other of them, plucking them from the skies forever. Earlier in the year, he’d flown sixty missions over Norway and France, watching as the panzer divisions below had thrust their shining black armour deep into the heartlands of the enemy, accomplishing in a few short weeks what the German army had failed to do in five years of fighting during the last war. And why? What had changed to make this possible? The answer was simple. It was the leadership of Adolf Hitler – his energy and power; his extraordinary intelligence and understanding; and yes, his will. He was the one who had made the difference. He had made the soldiers believe in themselves; he had carried them forward to victory.

And today the aura of power around the Führer was even more striking than usual. Everyone in the room was in uniform except Hitler, who was wearing a black double-breasted suit and a white shirt and tie, as if he were attending a funeral and not a military conference. The Führer was always meticulous in his dress, and Heydrich was sure that the suit had been a deliberate decision, meant to emphasize his displeasure at the current progress of the war. Heydrich’s report of Agent D’s short radio message concerning Churchill’s intransigence, which he’d sent to Hitler the previous day, had only increased the Führer’s angry gloom.

‘What does it gain us if we bomb all these towns? What does it matter if the population of London goes stark raving mad?’ Hitler broke out in a nervous, angry voice, gesturing with a dismissive wave at the map. ‘That fool Churchill will not give in. He doesn’t care if the bodies are piled ten high in the London streets. You’ve heard him speak. He wants this war. It’s what he always dreamed about. What does it matter that there’s no sense to it; that there’s no justice to it? England can have its empire, but Germany can have nothing. That is what he says. You can’t reason with a man like that. The only thing that would have made a difference is if you had given me air supremacy. And isn’t that what you promised me a week ago, Herr Reichsmarschall? Isn’t it?’

It was a rhetorical question thrown out while Hitler was pausing for breath, and Goering knew better than to respond. Heydrich was secretly impressed by the way Goering stood almost at attention and silently took all that the Führer had to throw at him. Hitler was giving full rein to his fury now. He was shouting and beads of sweat stood out on his pale forehead. In a characteristic gesture, he kept brushing the fringe of his falling brown hair back from off his face.

‘If we can’t control the skies, we can’t control the sea. An invasion is a waste of time. Any fool knows that. And so I’m to wait here doing nothing, listening to you telling me about incendiary bombs while Stalin builds more tanks. The Bolsheviks are the enemy, not the British. That is where the panzers must go, that is our destiny,’ Hitler shouted, jamming his finger down on the right side of the map, into the huge red mass of the Soviet Union. ‘I always knew this. I wrote it in my book fifteen years ago. Perhaps you should read it again, Herr Reichsmarschall – refresh your memory. My Struggle, I called it; Mein Kampf. I should have called it My Struggle to Be Heard.’

‘We will win,’ said Goering, injecting a note of certainty into his voice that Heydrich was sure he didn’t feel. ‘Just a little more time is all we need. And the RAF will be finished. They cannot withstand us; they are on their last legs.’

‘They are bombing Germany!’ Hitler screamed. ‘That is what they are doing. And you talk like it isn’t happening.’

Hitler took out his handkerchief and mopped his sweating brow. He held hard on to the side of the table, trying to control his breathing.

‘The invasion of England is cancelled, indefinitely postponed – call it what you like. You have all failed,’ he said, looking slowly around at his generals as if he were registering each face for subsequent review. ‘All of you,’ he repeated. His voice was soft but venomous, and the men closest to him instinctively took a step back. ‘Let it be the last time.’

Abruptly he turned and walked away from the table towards the side door by which he had come in. The conference was over.

Ten minutes later, Heydrich stood at the top of the entrance steps, watching the leaders of the Third Reich leave the Berghof one by one in their chauffeur-driven black Mercedes-Benz staff cars. In just the last few days summer had turned to autumn, and the canvas umbrellas over the outdoor tables flapped disconsolately in the light breeze that was blowing up from the valley below. It seemed to Heydrich far longer than a week since he had sat with Hitler on the stone terrace, drinking tea in the afternoon sunshine.

Looking down the steps, Heydrich remembered the Führer standing where he was now, waiting to greet the straight-backed British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in the week before the Munich Conference in 1938. Chamberlain had watery eyes and a wispy moustache, and he’d wanted peace in our time. Heydrich remembered afterwards the way Hitler had scornfully described how the Englishman’s hands had trembled when he used the word war. And Chamberlain hadn’t been alone. Lord Halifax, England’s foreign minister then and now, had also wanted to find a peaceful solution to ‘Germany’s legitimate demands’, as he’d called them. Hitler was right – it was Churchill who had changed the rules of the game. The fat man was in love with the sound of his own voice, filling the radio waves with his hatred of Germany and his talk of blood, toil, sweat, and tears. The false briefing paper exaggerating Germany’s preparedness for the invasion of England on which Heydrich had lavished so much time and care had made no difference. D had reported that Churchill wouldn’t back down – the old fool had meant exactly what he’d said in his rabble-rousing speech to the British Parliament back in June: ‘We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall never surrender.’ Fine words, but meaningless when the British Army had left all its heavy weapons on the beach at Dunkirk and their Home Guard was armed with spades and pitchforks. Without Churchill things might be different: sense might prevail. And D’s radio message had contained an idea for how Churchill might be removed from the equation – only a possibility, but certainly one worth exploring. A new door seemed to be opening just as an old one was closing.

Heydrich hadn’t mentioned D’s idea in the report that he’d sent to Hitler by courier the day before. It required a face-to-face conversation; it was too sensitive to be put in writing, and besides, Heydrich wanted to ensure it remained a secret between him and the Führer. He hesitated as he slowly buttoned his greatcoat and adjusted the peak of his SS cap over his brow. On the face of it, now was a perfect opportunity to see the Führer alone. He’d watched all the generals leave. But Hitler might not be receptive to new ideas in his present angry mood – an unscheduled intrusion might only infuriate him more. Yet Heydrich had a solution to offer to the very problem that was causing the Führer’s ill humour.

He ran the tip of his tongue round the edges of his lips as he weighed the odds, and then, making up his mind, he turned on his heel and re-entered the house. The great hall was empty, so he went on into the pine-panelled dining room and practically collided with the Führer’s valet, Heinz Linge.

‘Please tell the Führer that I wish to see him,’ said Heydrich. He was nervous and made it sound like an order rather than a request.

‘But the Führer is resting, Herr General,’ said Linge, who was under instructions to take orders from no one except his master. ‘The conference has ended. Everyone has left.’

‘Tell the Führer that that is why I am here,’ said Heydrich, standing his ground. ‘Because of what was discussed at the conference. I have something important to tell him. I need to see him urgently.’

‘Something that can’t wait. But something that couldn’t be said before in front of your colleagues. You intrigue me, Reinhard.’ Hitler had appeared silently behind his valet in the doorway, standing with his hands behind his back, but Heydrich was reassured to see that the Führer was smiling and appeared to have entirely shaken off his earlier irritation. He’d changed into a simple white military jacket, the same colour as Goering’s but otherwise entirely unlike the Reichsmarschall’s ridiculously flamboyant uniform.

‘Come, let us go out,’ he said. ‘We can walk together and enjoy the view down over the valley, and you can tell me what it is that is so urgent.’

They set off, walking side by side along the wooded path that led from the Berghof to Hitler’s teahouse on the Mooslahnerkopf hill, with the Führer’s Alsatian dog bounding along in front of them. Heydrich knew that this was one of Hitler’s favourite walks – he went to the teahouse almost every day when he was at the Berghof, and Heydrich had accompanied him there on several occasions, but never alone like now. It felt awkward to be walking casually with the supreme leader, and Heydrich watched his pace and walked with a slight stoop to ensure that Hitler wasn’t aware of his height advantage.

There was a cold grip in the air, but no clouds in the pale blue sky. To their right, the trees were laden with golden leaves turning to red before they fell, and to their left the spires and roofs of the small resort town of Berchtesgaden were clearly visible spread out across the valley floor three thousand feet below. All around, the mountains of the Bavarian Alps towered above their heads. Heydrich instinctively understood why Hitler loved this place and had chosen to make it his home. They were in the very heart of the Reich. There was an elemental energy in the air, in the vista, that reminded Heydrich of Caspar Friedrich’s painting, The Wanderer Above the Sea of Mists. Heydrich liked beauty – he could create it himself at home in the evenings when he stood at the window of his study with his violin, playing the Haydn sonatas that he’d learnt from his father when he was a boy. He understood it just as he understood the web of complex emotions that motivated the actions of his fellow human beings; but his understanding was clinical, an entirely cerebral analysis. Heydrich had no capacity for empathy whatsoever and, like his leader, he stood apart, utterly unmoved by the suffering of others. All that mattered to him was the use and pursuit of power.

They walked in silence, with Heydrich waiting for Hitler to open the conversation. The wind had died down and their footsteps on the hard ground were the only sound, apart from the tap of Hitler’s walking stick. The dog had gone on ahead. Soon they reached the point where the path bent out from under the trees, providing a panoramic viewing point. Hitler sat on the wooden bench looking out over the railings, and Heydrich followed suit.

‘I never get tired of this place,’ Hitler said meditatively. ‘I have tried to paint it several times from different angles, but it is too vast, too much a theatre in the round for me to capture on a canvas. Its essence escapes me.’

‘They say that Charlemagne sleeps under that mountain,’ said Heydrich, pointing across the valley to the majestic Untersberg, which reared up to a distant snow-capped peak thousands of feet above them, barring the way into Austria.

‘And they say that Jesus is the son of God,’ said Hitler tartly. ‘Why do you talk to me of Charlemagne? He’s been dead a thousand years.’

The riposte was typical of the Führer – always challenging those he was with, refusing to relax. But Heydrich was ready with his answer.

‘Because he did what you did,’ he said. ‘Charlemagne united the Volk; he made a Reich just like you have done. He had the will and the vision and the power to accomplish his mission. Men like you come rarely. They can change history, but there are always spoilers like Churchill who stand in their way, trying to destroy their work.’

‘And without Churchill the British would make peace. Is that what you are trying to say?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, you are probably right,’ said Hitler, nodding. ‘This war makes no sense for them and none for us. It’s like I have always said – I am England’s friend. There is room for them in the world and room for us too. We are all Aryans. But Churchill will not listen. He is the Bolsheviks’ greatest ally. I am sure Stalin has a picture of fat Winston in his bedroom in Moscow and that he kisses it with his filthy icons at night.’ Hitler’s sudden harsh laughter cut the air before he abruptly resumed the quiet, serious voice with which he had been speaking before. ‘What is it you are trying to tell me, Reinhard?’ he asked. ‘Don’t talk in riddles.’

Heydrich took a deep breath of the cold mountain air. He felt his heart beating hard under his uniform and a sense of vertigo rising through his body that didn’t come from their elevated position. He knew instinctively that this was his opportunity. With the credit for Churchill’s assassination, he could be Hitler’s deputy. With England out of the war, he would have succeeded where Goering and the generals and admirals had failed.

‘I think I can solve the problem,’ he said quietly. ‘I think I can remove Churchill from the equation.’

‘Kill him, you mean? How are you going to do that?’

‘As you know, I received a radio message from our agent yesterday. What I didn’t mention in my report is that he saw Churchill in person, and he seems to think that if he’s summoned to see Churchill again, then there might be an opportunity. I don’t know the details, obviously – it was a very short message.’

‘Well, get the details.’ Hitler snapped out the order. He got up from the bench, smoothing the crease of his black trousers into place, and walked over to the railings, standing with his back to Heydrich and looking out towards the mountains, drumming his fingers on the wood.

After a moment, he turned around. ‘We must not get ahead of ourselves,’ he said slowly. ‘I need to know whether this is a harebrained scheme or a real chance to eliminate Churchill once and for all. We don’t want to throw away our best intelligence asset on a thousand-to-one bet. But if it can be done, then let it be done.’ Hitler rubbed his hands together, a characteristic gesture when he was excited. He smiled, exposing his teeth, and his blue eyes glowed. ‘This is the best idea I have heard in a long time. The worms will have a feast when Churchill’s fat body goes underground. But you must be quick in finding out what is possible, you understand? East is where we must go. And before next year is too far advanced; before Stalin is ready for us. We must give our troops enough time – I have no intention to be another Napoleon, freezing to death in the Moscow cold.’

‘You can count on me,’ said Heydrich, getting up from his seat and standing to attention opposite Hitler, the image of a loyal soldier.

‘I hope so,’ said Hitler, looking searchingly at his subordinate. ‘We are playing for high stakes. Do not let me down, Reinhard.’

Hitler whistled and the dog came running up through the trees. ‘We will go back now,’ he said, turning towards the Berghof. ‘You have work to do. But next time you come, we will walk all the way to my teahouse. The view from the Mooslahnerkopf is excellent, even better than from here. And you can tell me more about this opportunity.’ Hitler smiled as he repeated Heydrich’s word. ‘I shall look forward to it.’

There was a spring in Hitler’s step now as he walked, and he hummed a tune under his breath. They rounded a corner and, looking up, Heydrich caught sight of the Eagle’s Nest, the retreat built for the Führer by the party faithful on a ridge at the top of the Kehlstein Mountain, three thousand feet above the Berghof. Thirty million Reichsmarks, five tunnels, and an elevator – an engineering miracle – yet Hitler hardly ever went there, preferring his small teahouse on the Mooslahnerkopf Hill. Heydrich smiled, thinking of the wasted effort. Results were what mattered; they were what led to advancement up the ladder of power. And now finally he believed he held the keys to the citadel dangling in his hand.

They parted in the hall. The map had been cleared away and the oak table moved back against the wall. It was as if the conference had never happened. Heydrich raised his arm in salute and felt Hitler’s pale blue eyes fixed upon him again, boring into his soul, before the Führer turned and walked away, releasing him back into the world.

IV (#ulink_100cf75f-302f-5d15-b99c-99b1179d1127)

They sat restlessly around the long table arranged in a kind of hierarchical order, with the least powerful among them exposed to the wintry draught by the door and the most important positioned closest to C’s empty chair and the fire behind it, which had died down to a black, smoky residue of itself in the last half-hour. There was no coal left in the scuttle, and nobody had volunteered to descend the seven flights of stairs to fetch more from the store in the basement.

It was ten in the morning outside, but inside it might as well have been the dead of night. The thick blackout curtains were kept permanently in place in Con 1, as this room was known – God knows why, as there were no other conference rooms in the building – and the only illumination came from two milky-white electric globes hanging by rusty metal chains from the ceiling overhead. Up until yesterday there had been three of these lights, but the one nearest the door had given up the ghost during the previous night’s air raid and Jarvis, the caretaker, had not yet got round to replacing it.

Far too busy ministering to C’s ceaseless stream of demands, thought Seaforth with wry amusement. By long-hallowed custom, the head of MI6 was always known by the single letter C – short for chief, Seaforth supposed. And even though he hadn’t been in the job that long, this C was already notorious for his enjoyment of life’s luxuries: the best Havana cigars; malt whisky brewed in freezing conditions on faraway Hebridean atolls; pretty girls in the bar at the Savoy. Not that Jarvis was likely to be providing them, thought Seaforth, glancing across at the bent, skeletal figure of the caretaker standing over by the half-open door.

Jarvis was clad as always in the same grey overall that reached down to just below his arthritic knees. Seaforth had never seen him wearing anything else – the old man would have seemed naked in a suit and tie. Service rumour had it that Jarvis had fought as a non-commissioned officer in the Boer War and killed five of the enemy with his bare hands during the relief of Mafeking, but Seaforth had no way of knowing if this was true, as Jarvis made a point of never discussing his personal history. He’d been at HQ longer than any of the current occupants or indeed most of their predecessors and had over the years become a fixture of the place, like the soot-stained walls and the ubiquitous smell of cheap disinfectant.

Seaforth had only recently been permitted to join these meetings of the top brass, and he knew that if Thorn had had his way, he would still be sitting marooned in his tiny windowless office at the back of the building. But C had overruled Seaforth’s boss in this as in numerous other matters, and now Seaforth sat two chairs up from the door, three chairs away from Thorn, and four away from C’s empty seat, savouring his position as an up-and-coming man.

With a sigh of contentment, he ran his hands slowly through the mane of his thick, dark hair and stretched out his long, athletic legs under the table, rocking slowly back on his straight-backed chair, expertly keeping his balance. Like everyone else in the room, he was working harder than ever, existing on small amounts of sleep snatched between air raids; but unlike them, he managed somehow to look healthy and rested, his good looks enhanced if anything by the faint thin lines that had recently begun to crease his brow.

The only blemish on his day so far was the cigarette smoke. It hung in a thick, blue-grey cloud in the unventilated room, blending with the fumes from the dying fire, and clung to Seaforth’s suit, making his eyes water. He hated cigarettes – the poor man’s narcotic. They reminded him of home, of labourers coughing in the gloomy public houses after work, drowning their sorrows in watered-down beer. He looked round the room at his fellow spies sucking greedily on their John Player’s Navy Cut and Senior Service and did his best to conceal his disgust. C’s cigars were different – a symbol of his power, like the thick Turkish carpet that began at the threshold of his office in the next-door building or the slow, careful way in which he spoke, the perfectly rounded vowels enunciated in his aristocratic, Eton-educated voice. C was old school, but old school with a new broom, ready to give the young generation its head. Not like Thorn with his Oxford University tie and his visceral suspicion of anyone who hadn’t been to a public school. As far as Seaforth was concerned, the last war had been about sweeping away men like Thorn, but so far, at least, Thorn didn’t seem to have got the message.

To hell with Thorn, Seaforth thought. Unlike Thorn, he was here on merit – because he’d been able to produce intelligence out of Germany that the rest of the pathetic pen pushers in this room could only dream of, and his recent summons to Churchill’s bunker had sealed his advancement to the top table. And there wasn’t one damned thing that Thorn could do about it. Seaforth grinned, thinking of the way Thorn hadn’t said one word to him on the walk back through St James’s Park, just stared down at his feet as if he were thinking of putting an end to it all – which would be no loss to the Secret Service, Seaforth thought. Alec Thorn had become an encumbrance that MI6 could most certainly do without.

Over by the door, Jarvis cleared his throat. ‘’E’s coming,’ he announced in a thin, wheezing voice, and seconds later C entered the room, dressed in a green tweed suit and a red bow tie. He was a tall, impressive figure, possessed of a natural authority and an air of resolution intensified by the piercing blue of his eyes. They were a tool that C knew how to use to his advantage. ‘Look a man in the eye, and if he shrinks, then ten to one he’s a bounder,’ was one of the chief’s favourite adages.

C was nearly five years Thorn’s senior, but looking at the two of them, chief and deputy chief, sitting side by side at the end of the table, Seaforth thought that Thorn looked far and away the older man. He was careworn, with worry lines etched deep into his wide forehead and thinning grey hair receding from a rapidly spreading tonsure on his crown. And he sat bent over in his chair, alternately turning his filterless cigarette over in his fingers and then tapping its fiery end against the overflowing ashtray in front of him. His suit was worn and the edges of his shirt collar were frayed. Everything about him contrasted with the dapper, handsome figure of C on his left. It wasn’t hard to see why Whitehall had picked C for the job when the old chief had been given his marching orders three years before.

‘All present and correct,’ said C, glancing affably round the table. ‘Now we can’t be too long today, I’m afraid. I’ve got to be at the Admiralty by twelve for one of their invasion conclaves. I assume everyone’s seen young Seaforth’s latest intelligence report about the German plans – the one that was circulated three days ago?’ he asked, waving a piece of densely typewritten paper with ‘Top Secret’ stamped across the top. ‘Good. Well, it’s pure gold as usual. Winston’s delighted with the quality of the intelligence, apparently, although not so happy with what the Nazis have got pointed at us across the Channel. Did he say anything about the situation when you saw him, anything you can share with us?’ he asked, turning to his deputy.

Everyone else had their attention fixed on Thorn too. The whole country was jittery about the threat of the invasion, and the people in the room had access to privileged information about how real the threat actually was. A week earlier, GHQ had sent out the code word ‘Cromwell,’ meaning ‘invasion imminent,’ to all southern and eastern commands. Church bells had been rung – the agreed signal for an invasion – and widespread panic had ensued.

‘The PM doesn’t see how they can invade without air supremacy, and they’re a long way from having that,’ said Thorn. ‘He says we’re going to fight to the death even if they do come, but we already know that. Still, it was inspiring to hear it from him first-hand.’

‘I’m sure it was. Must have been an experience for you too, young Seaforth. Not every day an officer of your rank gets summoned to an audience with the Pope. But, as we all know, the PM likes to get his information first-hand and you’re the one providing it this time, so full credit to you,’ said C, lightly clapping his hands for a moment. Everyone joined in except Thorn, who looked stonily ahead, keeping his eyes fixed on a photograph of Neville Chamberlain on the opposite wall that no one had got round to replacing since Chamberlain had resigned the premiership back in May after the Norwegian disaster.

‘And what we need now is more of the same,’ C went on. ‘All the powers that be want from us is news of when the bastards are coming and what they’re bringing with them, and Seaforth’s man is giving us exactly that – and on a regular basis.’

‘Yes, pretty convenient, isn’t it?’ Thorn said softly.

‘What, you don’t trust the source, Alec?’ C asked sharply, turning to his deputy. ‘Well, he’s been right every time up until now, you know – about the build-up of the expeditionary force, about troop movements, about bombing objectives.’

‘Except for when the Luftwaffe switched their attention from the aerodromes to London. He didn’t tell us about that, did he? Might have spoilt the surprise,’ said Thorn, whose doubts about the authenticity of Seaforth’s intelligence had mushroomed in the three days since their visit to Churchill’s bunker.

‘Well, there really wasn’t time for that, was there?’ said C equably. ‘The Germans were provoked into bombing London by us bombing Berlin. Stupid fools! Winston tricked them. The RAF couldn’t have withstood it much longer if the Luftwaffe had carried on attacking planes rather than people, or at least that’s what I’ve heard on the grapevine. There were just not enough Spitfires to go round. Instead Goering’s given them a chance to catch their breath and reinforce.’

‘You asked me a question,’ said Thorn, looking C in the eye and acting as though he hadn’t heard anything C had just said. ‘And here’s my answer: No, I don’t trust the source, and I don’t buy the idea that his access has improved because he’s just been promoted. It’s too damned convenient if you ask me.’

‘But people get promoted in wartime, Alec,’ C said smoothly. ‘You should know that – it’s one of the facts of life.’

‘I know it is. And not just in Berlin, either,’ said Thorn, making no effort to disguise his meaning as he darted a furious glance down the table at Seaforth and angrily ground out his cigarette in the overflowing ashtray. C watched his deputy carefully for a moment and then began to speak again.

‘So, moving on, our agent tells us that Hitler’s ordered a short delay to Operation Sea Lion while the expeditionary force is expanded and the rest of the heavy armour is brought up to the coast,’ he said, holding up Seaforth’s briefing paper again. ‘So this is what I need, gentlemen: reliable information about what’s actually happening on the ground – in Belgium, in France, all the way round to bloody Scandinavia. Soldiers practising amphibious landings; sailors kissing their sweethearts goodbye … you know what I’m talking about. We need to fill in the blanks. And quickly, gentlemen, quickly.’

C paused, glancing around the table, but no one spoke. Jarvis, standing behind his boss’s chair, darted forward and filled up C’s glass from a decanter of cloudy water.

‘All right, then,’ said C. ‘Let’s get to work. Is there anything else?’

‘We’ve had several decodes in this morning,’ said Hargreaves, a small bespectacled man sitting opposite Seaforth who was in charge of liaison with the boffins, as the communications branch of the Secret Service was euphemistically known. He had thick grey eyebrows that incongruously matched his grey woollen cardigan. ‘One of them’s interesting – it’s an intercept from yesterday. It’s quite short: “Provide detailed written report. What are the chances of success? C.” Seems like it’s someone called C somewhere in Germany who’s communicating with an agent here in England, although apparently there’s no way of pinpointing the receiver’s location without more messages. They’re checking to see if there are any other messages that have come in up to now using the same code, although it could well be the agent is using a different code to communicate back to Germany. That’s an extra precaution they take sometimes. I’ll let you know what they come up with.’

‘Someone pretending to be me,’ said C with a hollow laugh. ‘I’m flattered. Well, we all know that the Abwehr’s been dropping spies on parachutes and landing them from U-boats all over the place this year. But they’re in a rush – none of the agents are well trained, and some of them can’t even speak proper English from what I’ve heard. MI5 catches up with them all in a few days, and I believe they’ve even turned one or two, so I can’t imagine this one’s going to be any different.’

‘Except that most of them don’t have radios,’ said Thorn. ‘Can I see that?’ he asked, leaning forward to take the piece of paper that the small man had just read from.

‘Well, thank you, Hargreaves,’ said C after a moment, with a glance of slight irritation at his deputy, who was continuing to turn the paper over in his hand. ‘Like I said, I’m sure MI5 will deal with the problem. Now, let’s get to work. Alec, you stay behind. I need to pick your brains for a moment.’

C stared ahead with a fixed smile as the people around him got up from their chairs, gathered their papers together, and headed for the door. Once it was closed and the sound of voices had disappeared down the corridor, C turned to Thorn.

‘This has got to stop, Alec, you hear me? You and Seaforth have got to work together—’

‘Not together,’ interrupted Thorn angrily. ‘He works for me, in case you’ve forgotten. I’m his section chief, although you’d never know it to hear him talk.’

‘All right, he works for you. But he also works for me and for the PM and for the good of this dangerously imperilled country, and his agent in Berlin is producing intelligence product of a quality that we haven’t seen out of Nazi Germany in years. And just when we need it the most …’