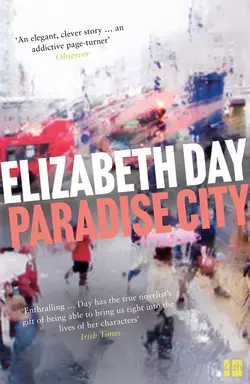

Paradise City

Elizabeth Day

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1348.51 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An audacious, compassionate state-of-the-nation novel about four strangers whose lives collide with far-reaching consequences.Beatrice Kizza, a woman in flight from a homeland that condemned her for daring to love, flees to London. There, she shields her sorrow from the indifference of her adopted city, and navigates a night-time world of shift-work and bedsits.Howard Pink is a self-made millionaire who has risen from Petticoat Lane to the mansions of Kensington on a tide of determination and bluster. Yet self-doubt still snaps at his heels and his life is shadowed by the terrible loss that has shaken him to his foundations.Carol Hetherington, recently widowed, is living the quiet life in Wandsworth with her cat and The Jeremy Kyle Show for company. As she tries to come to terms with the absence her husband has left on the other side of the bed, she frets over her daughter′s prospects and wonders if she′ll ever be happy again.Esme Reade is a young journalist learning to muck-rake and doorstep in pursuit of the elusive scoop, even as she longs to find some greater meaning and leave her imprint on the world.Four strangers, each inhabitants of the same city, where the gulf between those who have too much and those who will never have enough is impossibly vast. But when the glass that separates Howard′s and Beatrice′s worlds is shattered by an inexcusable act, they discover that the capital has connected them in ways they could never have imagined.