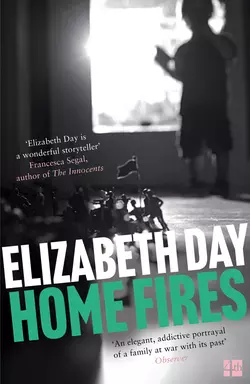

Home Fires

Elizabeth Day

A stunning, delicate portrait of a family bookended by war, Home Fires explores the legacy of loss, the strictures of class and the long road to redemption.Max Weston, twenty-one, leaves for his first army posting in central Africa. What happens to him changes the lives of his family forever. At home, his parents struggle to cope. The overwhelming love Caroline has always felt for her only child is now matched by the intensity of Max's absence. The silence is broken by the arrival of Caroline's mother-in-law, Elsa, who at the age of ninety-eight can no longer look after herself. After years of living in fear of putting a foot wrong in front of this elegant, cuttingly courteous lady, finally, Caroline has the upper hand.

Copyright (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc in 2013

This eBook edition published by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © Elizabeth Day, 2013

Elizabeth Day asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008221737

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008221744

Version: 2018-03-06

Praise for Home Fires (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

‘Elizabeth Day writes with unflinching, responsible honesty’ Sadie Jones

‘It’s to Elizabeth Day’s credit that she turns her back on the conventional narrative to explore the realistic consequences of war and violence on the women who, to cite the song to which the novel’s title alludes, keep the home fires burning. Day chooses the tough option at every turn, with the result that the novel becomes a powerful and, at times, heartbreaking account of Caroline and Elsa’s inability to deal with their crises. The prose is crisp and forthright, particularly when Day is describing the variations of violence, although she has a piercing eye for a telling phrase or a poetic flourish’ Irish Examiner

‘Brilliant’ Viv Groskop, Red

‘Day is an empathetic observer. She is meticulous in teaching and dissecting each sentence her characters experience … Home Fires conveys a broader version of life with the claustrophobia of emotional repression’ Eileen Battersby, Irish Times

‘Day has created a compelling study of grief, not least the conflicting ways in which the bereaved may wish to remember the dead … A bold novel, shocking in what it confronts and also in its suggestion that love will, ultimately, survive trauma’ Daily Telegraph

For my grandparents, who wanted me to write stories.

Contents

Cover (#u814cc6cb-cdb2-5282-a0aa-81d794db66c8)

Title Page (#uc0884c4d-7f18-5b32-9411-1c173efde51f)

Copyright (#u80ebf8a8-1c57-5e19-8306-1f7b1bfdcbf5)

Praise (#u7e24012d-8cd8-59d0-9ff8-253010b02ee4)

Dedication (#u0ded79ca-fbd9-5722-abf2-bb64fd4d3f06)

Prologue (#ub7947ad3-4977-5a9a-a63d-6e2e52211e99)

Part I (#u4eef91ef-ec05-5e24-88f3-3e443192ff02)

Elsa, 1920 (#u1882fbba-b393-51b7-884d-6675ef2eed76)

Caroline, 2010 (#u6acf4216-7bbe-5a23-9ec7-578a3c89d8c3)

Elsa, 2010 (#ubcb1b4ea-bc4c-5cfb-bcf5-caf9e36d2ea4)

Andrew, 1989 (#uc1c6b399-487c-5416-810a-8fb3ec6006be)

Part II (#ue31aea73-2ccd-5696-849b-d2c4614031bc)

Caroline (#uaec1dcf8-6a1d-5027-989f-9e9c24fbb3b6)

Part III (#litres_trial_promo)

Andrew (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa, 1919 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caroline (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa (#litres_trial_promo)

Caroline (#litres_trial_promo)

Andrew (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa, 1923 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caroline (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa (#litres_trial_promo)

Caroline (#litres_trial_promo)

Max (#litres_trial_promo)

Andrew (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa, 1936 (#litres_trial_promo)

Caroline (#litres_trial_promo)

Part IV (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa (#litres_trial_promo)

Caroline (#litres_trial_promo)

Caroline, Andrew (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsa (#litres_trial_promo)

A Note on the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

The water is closing in.

Her limbs are heavy. Waterlogged like wool left to soak.

Slipping, sliding, she feels herself go.

She smiles.

Nothing to stop her from falling.

Not now. Not any more.

Part I (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

Elsa, 1920 (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

They have come to see the marching men.

She is holding her mother’s hand, her fingers clasped around the familiar firmness of palm, knuckle, skin. She clings to it, tightly.

Her mother has told her that she must not, for any reason, let go in case they lose each other in the crowd. On either side of her, people jostle for space. She can hear the swish of ladies’ dresses, the dry coughs and small exhalations. All around, there are legs and waists and shoes. She fixes her gaze on the back of a pale blue skirt directly in front of her, the heavy material gathered up in an old-fashioned bustle that sticks out as if it is a face, as though the skirt is talking to her.

If she cranes her head round, still holding on to her mother’s hand, she can just about make out the street, appearing here and there in between the gaps left by shifting adult limbs. She wishes she could see better. She is always wishing for more than she has. When her father came back from the war, it was one of the first things he noticed about her: that she was too impatient, that she should be quiet and meek and talk only when spoken to.

‘Bite your tongue, child,’ he would say, even though he had been away for years and was a stranger to her.

She stares through the crowd, trying to focus on the procession. Her mother has told her this is a solemn occasion.

Solemn.

She likes the sound of the word, dense and slippery on the tongue.

There is a quick movement to one side of the blue skirt, a shifting swirl of something that Elsa takes several seconds to make out. Squinting hard, she sees it is the brown-beige lacquer of a horse’s hoof. From her vantage point, she can make out the silvery glimmer of its shoe, a crescent shape nailed neatly into the curve of its foot. The horse walks forward. The road is coated with sand and when the horse’s hoof makes contact with the ground, it thuds gently, the impact blotted by the granular surface.

The pale blue skirt with the bustle moves to one side so that Elsa now has an uninterrupted view of a broad sweep of street. A black gun carriage, pulled by six dark horses, draws in front of her. One of the horses is more jittery than the others, bucking its head against the bridle, nostrils flaring and shrivelling as it walks past. The crowd is quiet and then there is a rustling and when Elsa looks up she realises that it is the noise of everyone simultaneously removing their hats.

Behind the horse-drawn carriage, several hundred men are marching. Their feet thump with simultaneous regularity on the ground and behind that noise, there is another, less definable sound of the clatter and jangle of metal. Thump, clatter. Thump, clatter. As they pass, she sees the colour of their uniforms changing like a spreading bruise: blue into green into gunmetal grey, the shade of a thundercloud.

The silence of the crowd presses down on her. She turns back, tilting up her head to reassure herself her mother is still there. When she sees her, Elsa notices that her mother’s eyes are glinting, that the tip of her nose has reddened. She is still holding Elsa’s hand but her fingers have loosened. She seems distant, swallowed up by the men and women to her left and right, as if she is no longer Elsa’s mother but simply a person among many others.

‘Mama?’ Elsa whispers.

Her mother bends down, leaning on the handle of her umbrella, bringing her lips level to Elsa’s ears. ‘Yes?’ Her voice is distant, unspooling.

‘Why are all the men wearing different colours?’

Her mother looks at her strangely. ‘The soldiers wear different uniforms,’ she says. ‘Some are in the army, as Papa was, but some are in the navy or the air force.’

Elsa nods. She recites the names in her head like a poem: army, navy, air force, army, navy, air force.

The men file on by.

It was their next-door neighbour Mrs Farrow who had suggested the trip to London.

‘They are bringing home an unknown soldier to bury,’ she said one afternoon, sitting by the bay window of the drawing room, backlit by the fading sunlight so that Elsa could make out the fuzzy outline of downy hairs across Mrs Farrow’s cheek. Elsa’s mother seemed distracted but before she could say anything, Clara the maid brought the tea tray in, tripping over the edge of the woven silk rug and almost sending the crockery spinning to the ground. She managed to right herself just in time but her cap slipped down her forehead, giving her the appearance of a skittish, one-eyed shire horse. She looked flustered, embarrassed. Elsa felt sorry for her.

Her mother sighed and raised her eyebrows. Mrs Farrow glanced away, politely.

‘Thank you, Clara,’ her mother said. ‘That will be all.’

Clara bobbed her head and mumbled something under her breath. She had often overheard her mother saying the war made it difficult to get good domestic staff. Perhaps, now it was over, Clara would go. She hoped not. She liked Clara.

Her mother did not immediately respond to what Mrs Farrow had said, but instead busied herself with the tea. Elsa watched as she poured the milk, a growing pool of white leaking to the edges of the cup.

Eventually, her mother spoke. ‘Does it not strike you as being –’ she seemed to be searching for the right word, ‘a little morbid?’

Mrs Farrow laughed. ‘Alice, the whole war was morbid. I think the burial is intended as a symbol.’

‘A symbol?’ She passed the cup of tea across. There was a plate of cucumber sandwiches on the tray, the bread springy and thinly sliced, the translucent green discs slipping out like wet tongues. Elsa looked at them longingly. She was always hungry and hated herself for it. Her father said it was unladylike to display one’s appetite so nakedly.

‘Yes,’ Mrs Farrow continued, placing her cup and saucer on the lacquered side table. ‘All those poor people who were denied a funeral, who did not have a chance to grieve for their fathers or brothers or sons.’ She dipped her head. There was a small pause. ‘Or their husbands,’ she said, quietly.

The thought seemed to float between the two women, a leaden shadow that redistributed the weighted atmosphere of the room.

‘But of course, Alice, it is entirely up to you,’ Mrs Farrow said. ‘I merely thought that, as I intended to go and take Bobby with me, you and Elsa might wish to come along too.’ She stopped, before adding rapidly, ‘and Horace of course.’

The mention of her father’s name caused Elsa to breathe in sharply and to hold the air there, deep down in the pit of her stomach, where it would not make a sound. It made her feel small to do this, unnoticeable, a crumpled-up ball of paper that could be flicked to one side.

She sat on the chair by the fireplace not moving, straining to understand what was being said without appearing to eavesdrop, without drawing attention to herself. Through the corner of her eye, she could see her mother smiling her blank, colourless smile. Elsa had never met anyone else who could smile in quite the same way, so that whoever was on the receiving end of it could read whatever they wanted into the shape of her lips. It made her shiver to see it. The smile seemed to belong to another person; a borrowed piece of clothing.

She suspected that Mrs Farrow knew her father would not come, but the truth of it would not be spoken out loud. She glanced across at her mother. The smile was still there, fixed in place like glass in a window.

Her father didn’t want anything to do with the war, not any more. He couldn’t even touch the newspaper if there was a mention of the war on the front page. He would go out of his way to avoid the engraved plaque of names that had recently been erected at the bottom of their street. ‘Our Glorious Dead’ was the inscription across the top. Elsa thought that was an odd phrase. She couldn’t imagine a glorious way of dying. Even Our Lord Jesus who died on the cross – how could you call it glorious when he had nails hammered through his palms and feet?

But that was the phrase they had carved smooth and clear into the stone, the lettering cut so deep that Elsa could fit the tip of her little finger in the shallow grooves of the curving G. The stone felt cold to the touch.

On the morning they went to Westminster Abbey with Mrs Farrow, Elsa’s father was locked in his study working on his papers. They left him behind, even though he was the only one of them who had experienced the war first-hand.

Now here she is, holding her mother’s hand and standing amidst rows and rows of silent strangers. Above her, the russet-brown leaves of the sycamore trees quiver and twist in the sunlight. Mrs Farrow says it is ‘unseasonably warm’ for the time of year and Elsa thinks the men in uniforms must be hot, the collars of their tunics scratching against their neck as they walk. Hundreds upon hundreds of them seem to march past her and she imagines that each one of them has a family akin to hers that stretches all the way back from children to parents to aunts and uncles and grandparents and nieces and nephews and cousins and wives.

At school, the teacher had once drawn the family tree of Queen Victoria in chalk on the board. It had branches like a real tree, but made straight and long, and where you might have expected there to be a leaf, there was instead a name, a date of birth, of marriage and of death. She had been intrigued by that family tree, by the simple beauty of it, by the way everything could be connected. She had found the idea of it comforting.

She recalls it now, mapping out a family tree for each of these soldiers in her mind’s eye, the lines unravelling and criss-crossing through the generations, each interlinked branch expanding until she imagines the chalked-out marks covering the ground and the sky and the faces of the people who stood around her.

She begins to feel faint and her vision blurs around the edges. She blinks twice in quick succession to clear her sightline, dropping her head so that the muscles in her neck relax. When she looks up again, the procession is retreating into the distance, on its way to the Abbey. Someone has put a dented steel helmet on top of the coffin and Elsa finds herself wondering if it had been the unknown soldier’s helmet or not. How would they have worked it out? And if it wasn’t his helmet, whose was it? She does not like the thought of a soldier lying on his own, his head uncovered and defenceless. Would he be missing his helmet now, wherever he was? Wouldn’t his family want it back?

Her arm is aching. She wishes she could shake herself loose and let go of her mother’s hand. She twists back to look at her and sees that her mother is crying. She is embarrassed for her and shocked that she is showing such visible emotion in public.

But then Elsa realises that someone else is crying too. There is a tall woman in a pale pink cloche hat and threadbare gloves standing next to her. The woman has not made eye contact with anyone since she arrived a few minutes before the horse-drawn carriage came past. She had been flustered because she was late and her face had been covered in a light sheen of sweat. She had jostled her way to the front, bumping into Elsa as she did so but offering no apology. Instead, the woman had stood impassively to one side, her shoulders sloping. Her demeanour had not altered as she saw the coffin but now Elsa sees that tears are slipping down the woman’s cheeks, making her face appear misshapen. The woman is sobbing openly, oblivious to anyone else around her. The sobs are dry little hiccups and they catch in the woman’s throat as though she does not want to let go of them completely, as though she is frightened about what might happen if she forgets to control herself.

For a second, Elsa is ashamed for the woman and for her mother, but then her ears seem to pop, as if they had been filled with wax until that moment, and she hears the same scratchy sobbing sound replicated a dozen times over from all different directions. The whole crowd seems to be crying as one, their breaths heaving and creaking like a swinging rope.

She is unsettled by the strangeness of what is happening and, in search of reassurance, turns to find Mrs Farrow but her neighbour’s eyes are shaded by the tree leaves and Elsa cannot make out the expression on her face. Mrs Farrow’s son Bobby, who has been unusually quiet throughout the procession, is looking intently at his feet, scuffing the toe of his boot into the sand until his mother tells him to stop fidgeting. After several minutes, the woman in the pale pink cloche hat wipes her eyes with her gloved fingertips and turns to go. Slowly, the crowd thins out and disperses. Her mother lets Elsa’s hand drop and Mrs Farrow suggests they should start making their way home.

On the train back to Richmond, the four of them sit in a carriage, empty apart from an elderly gentleman in one corner, his left eye obscured by a glinting monocle. For a while no one speaks.

‘Alice, my dear, are you quite well?’ Mrs Farrow asks. The train judders forwards, hissing and spitting as it does so. Her mother nods, listless. Mrs Farrow leans across to pat the back of her hand. ‘That’s the spirit.’ She turns to look at Elsa and cocks her head to one side.

‘What a day,’ she says.

She has dark brown eyes that are almost black and Elsa finds that she cannot look away. She gazes back at Mrs Farrow without speaking. Bobby is swinging his legs against the train seat, his feet beating out an irregular rhythm.

‘Quiet now,’ Mrs Farrow says, resting a cautionary hand on his arm. He stops immediately and Mrs Farrow smiles, gently. She is a kind woman, Elsa thinks. Kind but firm.

She wishes she could say something to her, something that would explain how she feels. She wishes she could tell Mrs Farrow that she is scared to go home, that she does not like her father, that his return has changed everything for the worse, that her mother no longer loves her as much as she used to, that she does not know what to do about any of it, any of it at all. She wishes she could find the words, that she was old enough to know how.

Instead, Elsa breaks away from Mrs Farrow’s gaze and rests her head against the leather-lined upholstery. She does not want to have to think. After a while, she falls asleep. The war fades away in her mind: a bubble pricked before it reaches the ground. For the remainder of the train journey, her thoughts sink under a shroud of blankness, the flakes of its quietness falling like silent snow.

Back at the house, her father is nowhere to be seen.

‘I expect he’s still in the study,’ says Elsa’s mother, removing her gloves finger by finger. She leaves them on the hall table in a careless heap. Elsa stands by the doorway, not wishing to make a noise. Her mother looks at her and something about the way she is hanging back, wordlessly, seems to aggravate her.

‘What are you doing, dear?’ she says. ‘Close the door properly behind you and then . . .’ The sentence hangs between them, incomplete. A single strand of hair sticks to her mother’s forehead. Elsa wonders if she has noticed it there, the gentle itch of it against her skin. ‘Why don’t you go up and see if your Papa would like some tea?’ says her mother, walking into the drawing room.

She watches her go and whereas, in the past, Elsa might have felt a lurch of disappointment at her mother’s absence, she realises that her feelings have changed. She does not allow herself to need her, not like she used to. She thinks: I am no longer a baby.

Elsa, still in her coat, makes her way towards the staircase. She walks slowly, so as to eke out each second before she has to confront her father, before the shape of the day will be changed by his mood. She holds out her hands. The right one is shaking and she is irritated by this, annoyed with herself for not being able to steady her nerves.

Upstairs, she creeps down the corridor to her father’s study. The door is ajar, a glimpse of sunlight streaming through in a narrow beam across the carpet. For a moment, she is dazzled by the whiteness of the light. Then, she can see her father, at his desk. He is sitting upright in the oak chair, his arms resting on the blotting pad. There is no evidence that he has been working on any papers. He is staring straight ahead, not moving, barely even breathing, and facing a blank wall that used to have a picture on it. There is a faint, discoloured triangle on the picture rail where once it had hung. It had been a faded reproduction of a country scene: a silty river, a hay cart, a pale blue sky, a man in a bright red coat. Elsa wonders where it has gone.

She knocks on the door. Horace starts at the noise. He shakes his head, as though to rid it of something and then takes out a pile of loose paper from a drawer, setting it in front of him.

‘Yes,’ he says. His voice is tired.

Elsa walks in. ‘Good afternoon, Papa. Mama has sent me up to ask whether you would like any tea.’ The words tumble out quickly. She dislikes how childish she sounds.

He shifts the chair round so that he is looking directly at her. She takes a step backwards, pressing herself as close to the wall as she can. His eyes seem unfocused, glittery.

‘Tell me,’ he says, leaning forwards, his expression intent. ‘How was it?’

Briefly, she is not sure what he is asking about. And then she thinks: of course, the procession. He is interested after all.

‘It was . . .’

‘Well, speak up, child, speak up.’

Elsa clears her throat. ‘It was . . .’ she cannot think what to say. What does he want her to say? What is the right way to answer? ‘It was busy.’

‘Busy?’ He repeats, eyebrows raised. Then he chuckles, a quiet sound that makes her nervous. ‘What else?’

‘It was impressive, sir.’

He nods his head. ‘Good, good.’ He stands up, without warning, the movement so quick that Elsa is startled. He comes towards her, arms behind his back. When he gets to within a foot of his daughter, he stops. He seems to be considering something, the thoughts scudding across his brow. And then he brings his right arm round to his chest and she notices that his hand is clenched tightly in a fist.

Elsa flinches.

He looks at her, surprised, then shakes his head again: quickly, in a succession of jerky movements.

‘Did you think …?’ he starts. Then again: ‘Did you . . .’ He does not complete the question but goes to the desk and sits down so that his back, once again, is turned towards her. ‘Go,’ he says, the words sharp, unkind.

She stands there for a second too long. ‘For God’s sake, go!’ he shouts and as she is running out of the study, she hears a crash and then a falling sound.

It is only later that she realises he must have thrown something at the wall.

Caroline, 2010 (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

‘Caroline?’

She can hear Andrew calling her from downstairs but she can’t bring herself to answer. She lies on their bed, drifting in and out of consciousness, her thoughts half-disappearing into a grey sludginess that teeters perpetually on the brink of sleep. The curtains are drawn and fluttering gently as draughts filter through the gaps in the window frame.

They had been meaning to get the whole house double-glazed for months. Now, it seemed unlikely she would ever care enough to make it happen. Bricks and mortar did not seem to mean very much any more. The house had become a void; an unconvincing imitation of the home it had once been.

It seems almost funny to think of how concerned she used to be with how it looked, of how she had spent hours leafing through interminable sofa catalogues and pale, tasteful paint samples until she found the perfect combination of style and homeliness. She had liked the act of redecoration, of papering over something that she did not want to see. The smell of fresh paint, of clean, glossy newness, was soothing to her.

She had spent years refurbishing the house, stripping back the damp, acrid-smelling carpets, sanding the floorboards and covering them artfully with thick, woven rugs. She had painted every single wall and skirting board herself, from the duck-egg blue of the downstairs bathroom to the delicate ivory hues of their bedroom, offset by the wrought-iron bed frame and the dark, almost blackened wood of the wardrobe. She had discovered that you can learn taste quite easily. The home she had created for her family bore little relation to the Artex tiles and pebble dash of her youth.

There was one room she left untouched so that, now, still, after everything that has happened, the walls are magnolia, the floor is carpeted in a brownish-grey that does not show up the dirt. There are two stripped-pine bookcases on either side of the fireplace, the shelves devoid of books so that they stand empty as a toothless mouth. The wardrobe door bears the pitted marks of blu-tack and the shallow black dots of drawing pins withdrawn. The sheetless single bed, covered by a thin, tartan blanket, looks hollow. In this room, it is only the spaces that have been left behind.

Sometimes, when she passes the door, she thinks she sees him there in a lump beneath the blankets, sleeping in, wasting half the day, snoring gently. But it is always a trick of the light, or of the mind. And then she is forced to remember, all over again.

‘Caroline!’ Andrew’s voice resurfaces, this time more impatient. She knows she should answer but she thinks hazily that if it is important, he will come upstairs to find her. She stays sheltered underneath the duvet, numbed against any sense of time by those oblong white pills the doctor has given her to blot out the sharpest edges of her grief. Xanax, they are called, and the name makes her think of a creature from science fiction, an alien being burrowing away inside her, reshaping her internal moonscape.

‘These should make you feel a bit better,’ the doctor had said, in an attempt to be reassuring. But they do not make her feel better so much as remove the need to feel in the first place, so that her distress becomes strangely separated from her sense of self. The pain is still there but it begins to exist almost as a curiosity, a thing to be looked at and acknowledged rather than the awfulness that envelops her, that makes existing on any sort of practical level seem impossible.

Most of the time these days, she finds that the best way of dispersing the encroaching shadow, the slow puddle that spreads across her consciousness like spilt ink, is to take another pill. She is aware that she is ignoring the doctor’s advice. The printed label on the front of the brown plastic bottle tells her she is allowed a maximum of four over a period of twenty-four hours. Yesterday, Caroline took six, convincing herself that she needed them, craving the consolation. Also, if she is truly honest, part of her likes the thought that she is deliberately causing herself harm. There is something so comforting in the thought of self-destruction, in the thought of painting herself out altogether.

‘Caroline! Where are you?’

But there is Andrew to think about, of course. There is always him. Always, always Andrew . . . She hears him bounding up the stairs, taking them two at a time and the mere thought of this makes her feel exhausted. She is mystified that he can still possess so much energy. There is something unseemly about it, she thinks, something untrustworthy about his absurd good health. His hair has turned grey in the last twelve weeks but oddly this change appears to suit him, emphasising the prominent incline of his cheekbones and the dark hazel of his wide-set eyes. He has grown into his looks, the weathering of his flesh lending him an air of self-contained purpose.

By contrast, Caroline’s looks have been slipping away from her, as though her physical appearance is no longer under her control. Her skin, once fair and smooth, has turned sallow. She has dark circles under her eyes and a delicate web of faint wrinkles at each corner, radiating outwards. Her lips have narrowed and dried so that she finds herself licking them without thinking, running the tip of her tongue across the surface, feeling the sticky bits of skin dislodge as she does so. She has lost weight and although she has always disliked being plump in the past, has always tried to shift the extra heaviness around her belly and thighs, this new thinness does not suit her: her arms poke out of T-shirts and her hair has got thinner at the ends, sparse as straw.

She is not yet so far gone that she does not care about these changes. She has never been enamoured by her own appearance but these days it makes her sad to look at herself in the mirror. She sees an image of a face reflected but it does not seem to be her. There is no recognition at the image in the glass. There is nothing there, just emptiness, a lack of expression.

She feels defeated.

She senses Andrew sitting down on the edge of the bed, his weight causing her to roll slightly towards him. She thinks: why can’t he just leave me alone?

‘How long have you been in bed for?’ he asks and she hears in his voice the tone of disapproval. In fact, she does not know the answer. Her sense of time has become rather elastic but she knows she must offer him something concrete, so she lies.

‘About forty minutes or so,’ she says, choosing a number that is long enough to convince him she is telling the truth and yet short enough still to be within the realms of respectability.

He nods his head once, satisfied, and then he reaches out and strokes her hair softly. She has not had a shower for days and for a brief moment she worries that Andrew will notice the grease, coating the palm of his hand.

‘Darling, you must try and keep going,’ he says.

He is a good man, her husband. She knows this. He is good in spite of her badness, in spite of her being unable to pull herself together. He loves her still, even though he knows her love has gone somewhere else, has been lost and cannot find its way back.

‘There’s something I need to talk to you about,’ Andrew continues and she notices there is a small note of hesitation in his voice. She can still read him so precisely, so intimately. This knowledge, which used to provide her with such a sense of security, now seems only to frustrate her. She hates the thought that they have become so dependent on each other, moulding their shapes and their silences around the solidifying shadows cast by the other person.

‘It’s about my mother.’ Andrew’s voice drifts back. ‘She’s taken a turn for the worse. Mrs Carswell called up this morning and said she’d found her in her nightdress, lying in a heap at the bottom of the stairs. We don’t know how long she’d been there but she wasn’t making much sense, apparently.’ Andrew breaks off, waiting for a response. She opens her eyes lazily and meets his gaze. He looks sad and confused: a small boy. ‘It was already hard enough understanding her on the phone so goodness knows what state she’s in now.’ He shakes his head. Caroline sits up, propping the pillow against the curved bars of the bed frame so that the coldness of the iron does not press through her cotton nightdress. The effort of this single movement leaves her momentarily dizzy and unable to speak. She touches Andrew’s wrist lightly. He grabs hold of her hand too eagerly and lifts it up to his lips, brushing a kiss against her knuckles. She lets him hold her hand for a few moments longer and then slips it back down to the mattress.

‘Poor Elsa,’ she says and she can hear that the words are slurred. She tries to remember how many pills she’s taken today but she can’t. Not a good sign.

Andrew looks at her quizzically. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘Oh . . . fine.’ Caroline turns away. She glances at the rosy wash of the linen curtains held up against the fading evening light. There is a tap-tap-tapping sound against the window like pebbles scattering across glass. ‘Is it raining?’

‘Yes, I think so,’ Andrew replies. ‘It might even be hail by the sounds of it.’ He clears his throat. ‘Anyway, Mrs Carswell said that she’s not sure how much longer the current arrangement will be . . .’ he pauses, searching for the right word, ‘viable.’

‘Oh?’

‘She was very nice about it but she doesn’t think she can offer Mummy the necessary level of care. She seemed to think that Mummy might need someone with her on a more permanent basis and she suggested . . .’

Too late, Caroline can see where this was going. A scratchy panic rises up her gullet and lodges itself there.

‘Well, she suggested that maybe Mummy could come and live here,’ Andrew finishes, speaking the words quickly so that the damage is done as quickly as possible. ‘After all, we’ve got the room.’

She doesn’t say anything but the thought of looking after anyone else, of having to plan what to make for dinner, of having to exist on a day-to-day basis, of continuing normal life, of picking it up where they had left off as if she were picking up a fallen stitch in a piece of knitting . . . the thought of it overcomes her and seems to press the breath out of her lungs.

‘I know that the timing isn’t ideal,’ says Andrew. ‘But she is my mother, after all, and I feel I owe this to her.’

His voice is firmer now, less apologetic. He has a streak of steeled strength buried underneath all those layers of politeness and good-humoured kindness and a strong sense of right and wrong. It is part of the reason she used to love him so much.

‘Andrew, I don’t know if I can . . .’

‘Darling, I know you feel very weak at the moment –’ She looks at him, disbelieving. Does he honestly believe that is all it is? Weakness? ‘But maybe, just maybe, having someone else in the house might alleviate the pressure a bit.’

‘You think I’m wallowing, that I’m being self-indulgent.’

‘No, no,’ he insists. ‘I think you are having a terrible time, of course you are, but you can’t go on like this. At some point, you, we, both of us, we’ll have to get on with our lives . . .’

‘And forget Max ever existed?’

Andrew looks taken aback. ‘Neither of us will ever, ever do that,’ he says quietly. ‘But it’s been four months now –’

‘Three-and-a-half.’

‘OK, three-and-a-half months and I’m worried about you. I’m worried about these things –’ he takes the bottle of pills that is on the bedside table and rattles it in his hand. ‘You need to start living again. And part of that is being able to look outwards, to think about other people.’

She doesn’t say anything. She knows that this is Andrew’s way of coping: always doing things, thinking about the next thing, losing himself in involvement.

‘I’m not suggesting we move Mummy in immediately, but I do want her to come and stay with us. I know it’s an awful lot to ask but she’s old and fragile and she needs our help.’ He looks at her cautiously.

Caroline closes her eyes. After a while, she feels Andrew stand up and hears him walk out of the room, his footsteps going down the stairs. There is the sound of plates clashing as he loads the dishwasher. She is angry at that, at the resumption of normal service in the kitchen below, and she reaches, without thinking, for the pills, pressing down on the white lid of the bottle so that the catch releases as she twists. Caroline puts one in her mouth and swallows it with a sip of water from the glass on the bedside table. Within seconds, she eases into the familiar fog. Her thoughts relax. Her mind unclenches and fills slowly with the whiteness of space. The image of Andrew, washing plates, dissipates and his face is rubbed out, slowly, bit by bit, until there is nothing of him left and she falls into a state of numbness that is not quite sleep but near enough.

If she casts her mind back, she can remember the first time she met Elsa. The image comes to her completely intact: she is in the passenger seat of Andrew’s car, feeling the sticky rub of leather against her bare legs, and they have turned into a short gravel driveway and parked underneath the bending branches of a yellow-green willow. She has to be careful opening the door so that it does not scratch against the tree trunk and then she must squeeze herself out, shimmying through the narrow space, making sure her skirt doesn’t ride up her thighs as she manoeuvres herself upright and out of the car.

The house is medium-sized with latticed windows and a rambling rose climbing up the façade towards the tiled roof. The walls are painted the pink of iced cakes and there is a double garage with wooden doors to one side. Caroline has never seen a double garage.

‘Do they have two cars, your parents?’ she asks.

‘What?’ he says and then he notices her looking at the garage. ‘Oh, I see, no, only the one. They use the garage for storage mostly. Actually, there’s still some of my stuff in there.’

‘What kind of stuff?’

‘University stuff, old boxes of clothes, you know,’ he says. She nods her head as if the idea of university is unremarkable but inside she is impressed. She likes the fact that he is clever and more educated than she is. Caroline had never done well at school. Her father had always said she’d never amount to anything and, after a while, she began to think he was right and stopped making the effort. If her Dad could see her now, she thinks to herself, about to go for lunch with her boyfriend in a house with a double garage. That would make him stop and think.

She is nervous as she walks to the front door, her arm linked through Andrew’s. Sensing her unease, he smiles at her and pats her hand.

‘It’ll be fine,’ he says and a lock of hair falls forward over his left eyebrow. Caroline likes the way his hair does this. It was one of the first things she had noticed about him.

‘You’ll be wonderful,’ Andrew is saying.

She does not believe his reassurance, but she knows the appearance of confidence is important. She feels so lucky to be Andrew’s girlfriend, so surprised and flattered that he would choose to be with her that she is constantly on guard in case she does something wrong, in case she says something that will make him see who she really is.

The front door opens and a woman emerges, arms crossed over the front of her oatmeal-coloured cardigan, a small, precise smile on her face.

‘Andrew,’ the woman says and she leans forward, bending from her waist so that she does not step out beyond the doorframe, and then she brushes Andrew’s cheek against hers and kisses him but the kiss does not make contact so that all that is left is the suggestion of it.

Andrew’s mother is slender and elegant and taller than Caroline expected. She is wearing a tweed skirt that stops just above the calf, belted tightly around her small waist. Her hair is grey but she does not look old, even though Caroline knows that she is in her sixties.

She glances down at Elsa’s shoes. She has found that you can learn a lot about someone from their shoes. Elsa’s are made from expensive leather, buffed to a gleaming black patency, and Caroline is surprised to notice they are high-heeled, with a flat gold circular button on each toe. The shoes are beautiful but impractical, especially in the middle of the Cambridgeshire countryside. Caroline finds herself wondering whether Elsa has different, outdoors shoes that she keeps by the front porch or whether she has put these heels on because she feels the need to dress for the occasion. She makes a mental note of this, storing it for later.

‘And this must be –’ Elsa says.

‘Yes, Mummy, this is Caroline.’ He places the flat of his hand on Caroline’s back and she takes a step forward, leaning in at exactly the same angle as Andrew did for a perfunctory brush of the cheek, but Elsa puts out her arm and, slightly too late, Caroline realises she is meant to shake hands.

‘Oh,’ she stumbles. ‘Pleased to meet you, Mrs Weston.’

‘Do call me Elsa,’ says Andrew’s mother. ‘Mrs Weston makes me feel far too old.’ And then she takes her hand back a touch too quickly, moving it up to the silver chain necklace lying delicately across her collarbone as if checking it is still in place. For a few seconds, Elsa leaves her hand resting there, her long fingers static but tense, like a lizard on a rock.

‘The pink walls are very pretty,’ says Caroline and the words are out before she can stop them and when she hears them she feels stupid and wishes she hadn’t said anything.

Elsa gives a mock shudder. ‘Oh don’t! We’ve been wanting to get them painted ever since we moved in.’ She stands to one side, beckoning them indoors. ‘Come in, come in,’ and she leads them through a dark, windowless hallway into a room with mismatched armchairs and a cream sofa running the length of one wall. A large tabby cat is dozing in a basket by the fireplace and the sound of its purring mingles with the tick-tock of a grandfather clock. Andrew squeezes Caroline’s hand, then lets go and, instead of sitting down with her, walks across to the bookcase, where he stares intently at the orange paperback spines.

She stays standing, shifting her feet.

‘Where’s Father?’ he asks and Caroline thinks the word seems formal, stilted. She calls her own parents Mum and Dad. Or she did, before she left home. She pushes the idea of them away. She does not want to think of them, not now.

‘Oh, he got held up with some paperwork,’ Elsa says. ‘Lecture notes or something, you know what he’s like. Please, Caroline –’ She gestures to one of the armchairs and Caroline sits down, perched on the very edge of the seat because she is aware, all at once, that her skirt is too short. She presses her knees together, feeling the flesh between them get clammy and hot, and then she searches for something to say. She is so desperate to impress Elsa, so keen that she should not make a fool of herself or say something wrong. She wants, more than anything, to fit in.

Her nose starts to run but she has no handkerchief so tries to sniff discreetly.

Elsa is bending down to the gramophone player, putting on a record and placing the needle carefully on the vinyl. A piece of classical music starts up, hesitant and stuttering. Caroline can make out a piano and some strings. It is soothing, she thinks to herself, relaxing. Perhaps she can ask about the music. She clears her throat.

‘This is lovely,’ she starts, but even those words sound wrong – her accent too nasal, her vowels too flat. ‘What is it?’

Elsa walks across to the sofa, her heels click-clacking against the parquet floor. She balances herself on one of the arms, crossing her legs so that Caroline can hear the smoothness of her sheer stockings as they slide against each other.

‘Chopin,’ Elsa says. And then she smiles, brightly. ‘It is nice, isn’t it? The sonatas have always been a favourite of mine. What kind of music do you prefer, Caroline?’

Caroline feels her cheeks go hot. She does not know how to answer. She looks at Andrew for help but he still has his back to them, still examining something of interest in the bookcase.

‘I – I – don’t listen to much music,’ Caroline says. ‘But I like this very much.’ There is a pause, so she continues. ‘It’s so –’ she searches for the right word. ‘So delicate.’

Elsa nods her head, slowly, obviously, as though she is making an effort to be encouraging. ‘I agree,’ she says in a way that suggests exactly the opposite. ‘Nothing quite so elegant as the tinkling of the ivories, is there?’ She glances at Andrew. ‘What do you think, darling?’

He turns around, hands in his pockets. ‘What would I know, Mummy?’ He smiles, affectionate, joshing. ‘I only listen to young people’s music these days.’

Elsa laughs. She throws her head back as she does so, revealing the soft pallor of her throat.

‘Oh darling, I hope that’s not true,’ Elsa says. ‘You’re not getting all rebellious on me now, are you? Do you know, Caroline, he was always such a serious little child. He used to look at me exactly the way he is now, even as a baby. The Steady Gaze, we used to call it.’ She cocks her head to one side. ‘Does he do that to you?’

Caroline shakes her head, unsure of how to reply. She stares down at the hem of her skirt, wishing she had chosen to wear something different. Before coming, Andrew had told her his mother was fashionable, that she liked clothes, and Caroline had taken this literally. She had worn the most up-to-date items in her wardrobe: a bright yellow miniskirt and a chiffon blouse with swirly patterns, tied at the neck with a bow. But now she saw that had been a mistake. Andrew did not mean fashionable – he meant classic, refined; he meant his mother had taste and wealth and breeding. He meant his mother was posh, but, like all posh people, he would never have seen the need to say it.

She feels acutely uncomfortable sitting here, in her out-of-place clothes and her overly styled hair. Elsa seems to have no make-up on other than a small circle of blush on each cheek. Caroline’s lashes are caked in mascara. Her lids feel heavy as she blinks. She is worried that her eyeliner has smudged, that there are dark, unbecoming patches of black on her skin that everyone is too polite to mention. She has lost the thread of the conversation and it is only when she hears her name again that she resurfaces.

‘So,’ Elsa is saying, ‘Andrew tells me he found you on a doorstep?’ She smiles as she asks the question but Caroline can sense the implied disapproval, the deliberate intimation that the idea of this is somehow ridiculous, to be made fun of.

‘Yes,’ Caroline says. ‘I was locked out.’

In fact, she had been crying. A few weeks earlier, she had run away from home with £20 in her pocket. She had caught the train to London, found a room to rent in a dingy flat in Notting Hill and, after a few days, got a job as a cinema usherette in the Coronet. She spent the evening of her nineteenth birthday handing out mini-pots of Italian ice-cream and a middle-aged man had cornered her by the Ladies’ and tried to stick his tongue down her throat before she kneed him in the groin, letting the ice-cream tray fall to the ground. She lost her job after that. She had soon realised that city life was not as liberating as she had expected it to be. She was glad to be away from her parents but she found she missed the familiarity of her childhood home, the dreary pebble-dash bungalow beneath the flight path in Sunbury-on-Thames. She had been so unhappy there, had hated it so much and yet now, when she was finally free of it, paradoxically, she found she missed it. Still she kept trudging on, attempting to forge a new life for herself, eating unheated soup out of cans, buying clothes in second-hand shops, trying not to speak to anyone, not wanting to be discovered. She felt as though she could have slipped through the seams of life altogether and no one would notice she had gone. She became small, unobtrusive, silent. She left no trace. And then, one day, she had lost her keys, sat on her doorstep and started to cry. And that was how she had met Andrew.

‘She was in tears,’ Andrew is saying now. He is crouching down by the basket, tickling the cat’s chin with the tips of his fingers and grinning at Caroline as he talks. ‘I could never resist a beautiful damsel in distress so I did what any decent man would do and took her for a coffee to warm her up.’ He stops and Caroline is flushed by the compliment. She has never thought of herself as beautiful before. Her shame dissipates, replaced by pride that Andrew wants to talk about her, wants to prove how much he cares in spite of his mother’s unconcealed belief that he could do better. ‘I’m incredibly grateful that she said yes.’ He winks at her and she is flooded with happiness. ‘So, here we are.’

Elsa smiles, her lips stretched like a rubber band on the brink of snapping. ‘Well, that’s a charming story,’ she says, getting up in one swift, fluid movement. ‘Do please excuse me. I must go and check on the chicken.’

After his mother has gone, Andrew gets up and comes across to Caroline, bending down to murmur in her ear. ‘She likes you,’ he says and Caroline is so surprised by this obvious lie that she laughs.

‘She thinks I’m common.’

He shakes his head, bringing his face close to hers so that the tips of their noses almost touch.

‘No, she doesn’t.’

‘She thinks I look cheap.’

‘You look gorgeous. That’s what I think.’

Caroline giggles, feeling the knot in her stomach relax.

‘She just takes a while to warm up,’ Andrew says. ‘That’s the way she is. Don’t worry so much.’

He traces the curve of her cheek with his fingers. She thinks, not for the first time, that he must have had practice at this. He is ten years older than her, so it stands to reason he would have had other girlfriends; girls who were prettier, classier, cleverer than her; girls from good families who knew what a Chopin sonata was. But instead of feeling downcast by this, it makes her even more determined to please him, to keep his attention. She wants to be better than the lot of them. She wants to prove his mother wrong. She wants to love him more than he has ever been loved before. And she can do it. She knows she can. She just has to keep trying.

Elsa, 2010 (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

Elsa has been told by Mrs Carswell that she is going somewhere. She knows that she has been told this many, many times but still she cannot quite remember where it is she is meant to be going. If she could just reach out that little bit further, she thinks, if she could only stretch the thread of memory that tiny bit more, she would be able to grab hold of the elusive fact.

She looks around her for clues and finds she is sitting in her customary armchair and there is a battered leather suitcase in the corner of the room, staring at her accusingly.

Where am I going? she asks herself.

Will the journey be long?

What will happen when I get there?

Much of Elsa’s life nowadays seems to be taken up with the thankless task of trying to remember things. It is as if she is trying to see something clearly through a frosted window – the outline is visible but the detail, the crucial sense of it, remains cloudily lost.

She blames Mrs Carswell for this. Elsa is waging a secret war against her daily. She still calls her ‘the daily’, at least in her own mind, even though, for the last few months, she has been doing considerably more than simply cleaning the house. Mrs Carswell is a fat, red-cheeked publican’s wife wreathed in purposeful cheerfulness that Elsa finds especially irritating. It is Mrs Carswell’s briskness, tinged with condescension, that is so galling. It is always ‘How are we today?’ and ‘Shall we tuck this blanket in a bit? We don’t want to catch cold do we?’, always delivered with an inane grin, always accompanied by the rapid, forceful movements that make Mrs Carswell’s flesh rise and wobble like a baking cake. Elsa will sit there, the blanket now tucked in so uncomfortably tight it seems to cut off the circulation in her legs, and the resentment will rise silently within her until she becomes more and more furious and determined to say something.

But she is never able to find the right words. Ever since she’d had that fall a while back, she has not been feeling herself. And then there had been a stroke – at least, that’s what she has been told; all she can remember is waking up one morning with a burning sensation in her head, unable to move – which leaves her frustratingly incapable of expressing herself. She knows exactly what it is she wants to say and yet she can never quite remember the way to say it. When she does try, her tongue lolls loosely in her mouth and her voice comes out as an embarrassing groan. It is mortifying. She used to be so eloquent, so fluent in her speech, so intolerant of other people’s grammatical errors and sloppy vocabulary and now here she is, an old saliva-drooling nuisance pushed around and patronised by her former cleaner.

When she tries to describe it to herself, the metaphor she comes up with is a crack in the pavement. There is a crack, a fatal gap, between Elsa’s thoughts and the capacity to act on them and in this crack grows a thick weed of festering anger, almost entirely directed at Mrs Carswell, who knows nothing about Elsa’s blackly murderous thoughts.

Sometimes Elsa entertains herself by imagining a giant speech bubble magically appearing above her head containing all the vicious insults passing through her mind at any given time. She envisages Mrs Carswell turning round from the washing or the cooking or the lighting of the gas fire or whatever menial task she was engaged in and being confronted by the brutal reality of what was going on in Elsa’s head. Elsa can while away several happy hours imagining her reaction: Mrs Carswell’s mouth would slip open slackly, the expression one of horror compounded by the sudden, inescapable knowledge of how much she was hated. She would scream, perhaps, or whimper in distress. Then Mrs Carswell would run out of the house, shrieking, never to return.

Well, thinks Elsa grimly, one can but dream.

For the last couple of weeks, Elsa had been taking her revenge in small but deadly ways. A few nights ago, she had unscrewed the hot water bottle cap and let the tepid dampness seep all over her sheets. It had taken her the best part of an hour to get her arthritic fingers to do what she wanted them to, but she had managed it eventually and when Mrs Carswell came in the morning to get her out of bed, there was a delicious moment where Elsa noticed the glimpse of panic on her face when she thought her increasingly infirm charge had wet herself. Ha! Elsa thought. That’ll teach her.

‘Dear me, what have we here?’ Mrs Carswell said, roughly pushing Elsa over on to her side so that she could inspect the cotton nightdress clinging wetly to her withered thighs. ‘What have you done to yourself, eh?’ She tutted gently under her breath before spotting the hot water bottle, lying flaccid and shrunken at the foot of the bed. ‘Oh my stars,’ said Mrs Carswell, picking up the offending object and examining it closely. ‘How on earth did that happen? I thought I screwed it on ever so tightly.’ She looked at Elsa levelly, her piggy little eyes flashing with something like distaste. ‘Well. It’s a mystery.’ But Mrs Carswell was no fool. She knew what this meant. Still, she wasn’t about to let on. ‘Let’s get you up, shall we?’ she said with exaggerated brightness and she started dressing Elsa in dry clothes, managing to strip and remake the bed with such efficiency that within half an hour, the episode seemed barely to have happened. ‘There,’ said Mrs Carswell, clapping her hands together once the task was completed. ‘All done. Let’s get you some breakfast, shall we?’

Today, Elsa is taking a different approach. She has been left in the usual armchair by the single-bar gas fire in what Elsa calls the sitting room and what Mrs Carswell insists on calling the lounge. From here, Elsa can hear the tell-tale ping of the microwave that signifies Mrs Carswell is making lunch. A wheeled table, of the sort they have in hospital wards, has been moved over to the side of the chair, the white metal tray lifted several centimetres over her knees. On the tray is a single spoon with which Elsa is expected to eat her food. The indignity of that spoon enrages her. She is perfectly capable of using a knife and fork, even if it takes her longer and the results are rather messier than she would like. But to be reduced to a spoon – such a babyish piece of cutlery! – makes her feel so powerless, so demeaned that she can barely look at it without feeling her eyes fill with unintentional tears. After staring at it for a while, she tells herself firmly to lift her right arm (it is almost impossible to get her left side to do what she wants) and slowly, she feels her shoulder socket click into action. She lifts her arm, heavy as a flooded sandbag, and feels a shooting pain across her chest as she does so. Elsa winces and pauses for a second to gather her strength. Finally, she manages to get her hand on to the table, to close her knotted fingers around the spoon handle and to hide it, as quickly as she can, under the chair cushion.

She can feel her heart beating lightly against her chest in a breathless tap-tap-tap. A flash of memory comes to her of when she was a small girl, lifting up a dying sparrow from the patch of garden behind the house. The bird lay in her cupped hands, its beady eyes swivelling frantically and Elsa had wanted more than anything to help it, to soothe its panic with a friendly touch, but she found she was unable to. The bird twisted uncomfortably but had no strength to escape. She noticed its chest twitching and realised after a moment that this was the sparrow’s heart, twitching frail and fast against its feathers, pressing so forcefully against the bird’s delicate flesh that it looked as though something were trying to escape and burrow its way out. The thought disgusted her. She dropped the bird on to the ground and ran back into the house.

And then, another memory: this time, she is wearing a cotton nightdress that is too thin to keep her warm even in summer. She is walking noiselessly down the hallway, being careful to avoid the creaking floorboards and it is night-time, the heavy sort of darkness that envelops the first hours after midnight. She is pushing open the door to her mother’s room, reaching up with one arm to turn the handle, the brass cool and dry against the palm of her hand. She stops in the doorway, until she can make out the recognisable outlines of the chest of drawers, the heavy oak wardrobe and the bedstead. She starts to walk on tiptoe towards the bed, inhaling her mother’s familiar sleep smell – clean linen mixed with the faintest traces of her hair and the sweetness of her sweat. She can hear the rise and fall of her slow breathing, calmer than it is in the daytime. And then she can hear another, unfamiliar sound, a throaty, deeper noise that she cannot place. But before she has time to work out what it is, the bed jolts and a large, dense shape rises up from the mattress. She hears the shape take three strides across the floor and she feels herself being lifted up, her chest squeezed with the force of two hands pressing against her skin. ‘This is no place for little girls,’ says a male voice and then she finds herself in the hallway, her mother’s bedroom door slammed shut behind her. She stares down at her bare feet, her toes turning white-blue with the cold, and she tries for a while to make sense of what has happened but she can’t and so she walks quietly back to her room, feeling scared and alone. She thinks: I wish my father had never come back.

Elsa starts at the thought, as though she has woken, quickly, from a desperate dream. The cushion she has been leaning against slips to one side and she cannot get comfortable again. She sees the brown suitcase, lurking in the corner like a shadow, and grimaces. It is strange how these glistening shards of the remembered past come to her, strong and clear as though they were more real than what is happening to her in the present. They are never the memories she expects to have – first days at school, weddings, family Christmases – those regular friends that become little more than well-thumbed photographs the more they are leafed through. They are, instead, memories that she had forgotten she possessed, memories that had been buried deep beneath the seabed for years before rising: a gleaming piece of driftwood, the bark stripped back to reveal an untouched whiteness glimmering in the bleakness of daylight.

She calms down after a while and can feel the reassuring lump of the spoon’s outline underneath her thigh. She hears Mrs Carswell opening the fridge door, humming off-key as she does so. The radio is tuned to a station that plays unchallenging popular music for older people and Elsa can make out the occasional tinny chord of easy jazz, her irritation rising with each syncopated beat. When Elsa had been herself, the radio had two settings – Radio 3 for classical music in the morning and evenings and Radio 4 for the news and The Archers in between. The wireless dial never wavered from this strict routine: if Mrs Carswell had ever listened to her commercial rubbish when she came to clean, she was always scrupulously careful to retune it at the end of her two-hour session. Now, Elsa noticed, she doesn’t bother. Dear God, it is boring waiting for a lunch that she knows will taste exactly the same as her lunch yesterday and the day before that. She tries to entertain herself by taking flights of fancy in her mind but after a while, even her own thoughts bore her. She remembers a book she once read when her eyesight was still workable about a man who had suffered a brain haemorrhage and who had woken up with his mind perfectly intact but unable to move. The only way he could communicate was by blinking a single eyelid. It had struck Elsa at the time as a peculiarly nightmarish existence but now, horribly, she feels she is stuck in a similar limbo. Of course, she is still able to speak after a fashion but it takes so much effort to form the words and she is aware that her periods of complete clarity are becoming more and more irregular. She can shuffle around on her own but her movements have to be self-consciously slow and considered and planned some time in advance of being executed. It is the helplessness she couldn’t stand: the enforced dependence on other people.

It embarrasses her to be so reliant on Mrs Carswell, a woman she had always looked down upon and poked fun at in the past. She had not meant to be cruel or supercilious, but it was rather that her relationship with Mrs Carswell was marked by the benign exercise of an employer’s power over her employee. Mrs Carswell had understood this perfectly well. She was staff. Elsa was a lady. They belonged to different classes, different backgrounds, different life experiences. They were fond of each other but only in a distant, careful sort of way. At Christmastime, Elsa would give Mrs Carswell an envelope with two crisp £20 notes and a box of chocolate-covered Brazil nuts that she knew were a particular favourite. Mrs Carswell would be genuinely grateful, her face flushed with pleasure. Every year, Elsa received a card in return, always festively emblazoned with a garish snowman or a winter skating scene, always written with economy in Mrs Carswell’s roundly looped handwriting. ‘To Mrs Weston,’ it would say and then there would be the printed line – Happy Christmas or Season’s Greetings (which Elsa sniffed at for being politically correct) – and then Mrs Carswell always added the words ‘with best wishes from Barbara and Doug’ even though Elsa had never spoken more than two sentences to Doug and never once referred to Mrs Carswell by her Christian name.

But Elsa’s increasing decrepitude has changed all that. Now Mrs Carswell is in control and although she remains polite and respectful, there is part of Elsa that suspects she rather enjoys the shift in circumstance. Mrs Carswell is no longer intimidated by her employer, by her big house or her clever words, and she no longer exercises that quiet, particular deference that Elsa had always believed was her due. The balance of power has tipped in Mrs Carswell’s favour but Elsa is not surrendering without a fight.

She can hear Mrs Carswell dimming the radio’s volume in the kitchen – this is another thing that drives Elsa mad: why does she not turn the blasted thing off when she is leaving the room? It’s a terrible waste of electricity, she thinks to herself, but people never seem to care nowadays about things running out.

Mrs Carswell’s footsteps squeak on the linoleum as she walks down the corridor towards the sitting room. Elsa holds her breath in anticipation. She shifts in her seat.

‘Here we are then,’ Mrs Carswell says, carrying a tray through the doorway. She places it on the table with an unnecessary flourish. There is a plastic cup of water, a small glass bowl of tinned fruit salad and a plate of glutinous-looking pasta shells covered in a virulent red sauce that had obviously come straight from a packet. ‘Let’s just get this serviette in place,’ she says, apparently oblivious that the word ‘serviette’ causes Elsa to wince in pain. She unfolds a cheap blue paper napkin and tucks it into Elsa’s collar, rough knuckles grazing the stringy veins in her neck. ‘There we are.’ Mrs Carswell straightens up, casting her eye approvingly over the scene in front of her. There is, Elsa thought, something so self-satisfied about her. Then Mrs Carswell notices there is no spoon. Elsa can see it happen: the trace of a smile fading gradually from her face, the brow becoming furrowed, her expression clouding over with uncertainty.

‘What the . . .’ Mrs Carswell shakes her head, causing her helmet-shaped hair to quiver like a set jelly. ‘Well, I’ll be jiggered. I could have sworn I brought that spoon out here.’ She stands for a second with her fleshy pink arms crossed in front of her ample chest, assessing the situation, a vague crinkle appearing between her eyes.

Elsa is delighted. She couldn’t have hoped for a better reaction. It’s the confusion she relishes the most: Mrs Carswell, who was always so sure of herself, always so practical and efficient, is now reduced to second-guessing and hesitation. Let her feel what it’s like to be confronted with one’s own forgetfulness! Let her be filled with doubt, with the encroaching sense of paranoia that her faculties are not what they once were!

Elsa feels her insides contract with joy at the point she has scored and, before she can stop herself, her lips curve themselves into a crooked little smile. She notices too late that Mrs Carswell is looking at her curiously, her head tilted appraisingly to one side. ‘I don’t suppose you’d know where that spoon went, would you?’ she says, her voice light and good-humoured. She throws her head back and laughs, a full-throttled sound. ‘Well I never,’ she says, bubbling with jollity. ‘You little minx. You’ll be the death of me, you will.’ Mrs Carswell wags her finger vigorously, as though remonstrating with an endearing toddler. She makes a great show of searching for the missing spoon as if it were a game Elsa had devised purely for her enjoyment. ‘Is it here then?’ she asks gaily, bending down and looking underneath the piano pedals and then when she sees that is not the hiding place, she potters brightly around the room, examining increasingly ludicrous objects in order to make the joke last even longer. ‘Ooh, I know,’ she says, picking up one of Elsa’s precious enamel pill boxes, ‘it’s in here, isn’t it?’ Mrs Carswell opens the delicate lid with her thick fingers and Elsa holds her breath. The worst of it is that Mrs Carswell thinks she is being a terribly good sport. She thinks that Elsa wants her to make light of it, to include her in the pretence when, in actual fact, it makes the whole episode gruesome and painful because Elsa is powerless to put her sharply in her place and tell her to stop being so silly. She tries to form a suitably icy put-down but her mouth feels too thick and slow. When she does finally ask Mrs Carswell to stop, the sound comes out as ‘shop’ which triggers a whole new comic monologue. ‘Oh I see, you want me to go to the shop and buy a new one, do you?’ Mrs Carswell giggles, her cheeks pink with exertion. ‘Well, I’m afraid I’m not made of money. I can’t very well go and do that when you’ve hidden it, can I? Ooh, you little tinker! I shall just have to get another spoon from the kitchen until you tell me where it is.’ And off she bustles, repeating, ‘Well I never, well I never’ under her breath.

Elsa watches her go. She is crushed by exhaustion. How could it have gone so awry? She can feel the tears starting again. Since the stroke, she seems to be unable to regulate her feelings in the way she had been able to in the past. Everything appears heightened: the most trivial thing can make her weep while the mere sound of her son’s voice at the end of a telephone line is often enough to give her a surge of love. She has become emotionally incontinent. Now here she is with tears streaming down her cheeks, their wetness serving only to underline the dryness of her skin. She wipes her face with the back of her hand. She would have liked a handkerchief but there is never enough time to get it out from the sleeve of her blouse. Lately Mrs Carswell has got a bit slapdash about dressing her and today Elsa is wearing an over-the-top cardigan with an extravagant feathered collar over a plain, checked shirt. Looking at these mismatched garments somehow makes everything seem worse and the tears start dropping on to her blue serge skirt, leaving damp dot-to-dot circles in the fabric. And still she cannot remember where it is she is meant to be going.

She must pull herself together. She does not want Mrs Carswell to see her like this. It would be too undignified. But she can hear Mrs Carswell’s footsteps and then it is too late because she is in the room, crouching down next to Elsa, her fat, kindly arms around her, saying ‘There, there. No harm done’ and being so nice and so sincere in her comfort that Elsa feels even worse. Why had she been so mean to Mrs Carswell? What had prompted her spitefulness? She cannot remember. She is suddenly awash with gratitude and wants simply to snuggle into Mrs Carswell’s chest and be protected from the harshness of the world around her. More than anything, she wants to be looked after; she wants not to have to fight this constant battle to defend herself, to pretend her mind is intact. She wants finally to surrender, to snap the worn rope that connects her to the rational present and to allow her thoughts to dissolve like melting granules of sugar in a mug of hot, hot tea.

‘It’s because you’re leaving, isn’t it?’ Mrs Carswell is saying, patting Elsa’s hair softly with the palm of her hand. ‘Oh you poor darling, there’s nothing to be upset about now, is there? Andrew will take good care of you, of course he will. Yes, of course he will.’

And then Elsa remembers: she is going to live with her son and his wife in Malvern. Her son is called Andrew and his wife is called . . . what is her name? She can picture his wife so vividly – peaky face, too much make-up, a skirt that is too short, hair all puffed up like she had something to prove – and yet she cannot put a name to her.

And there was a child too, wasn’t there? A son, blond and broad and beautiful. A son called Max. Yes, she thinks, Max, that was it, and she can remember him also, sitting by the fire, his breath smelling of coffee walnut cake, the crumbs of a just-eaten slice falling on to the rug, a shame-faced smile when he realised he was making a mess.

It is all coming back to her, she thinks in a spasm of clear-sightedness, but Max . . . something had happened, something bad. What was it? Why couldn’t she put her finger on it?

And as she is thinking these thoughts, the questions chasing round her mind, a half-recalled memory comes back to her, the edges of it gleaming like the planes of a cut diamond catching the light.

It is a memory of a christening.

Andrew, 1989 (#u87c53aff-a294-54c1-a407-d3d1962a57c6)

He has not been particularly involved with the preparations for Max’s christening. In truth, he is not even sure that he wants his child blessed by a God he doesn’t believe in, but Caroline has been quietly determined that it is ‘the right thing’ to do and so he has gone ahead with it. These kinds of things are important to her.

In the end, the service goes without a hitch. Max is extremely well behaved until the moment Caroline hands him over to the vicar, at which point his face screws up tightly and there is a dangerous semi-quaver of absolute silence while he breathes in, ominously gathering his strength before emitting the most gargantuan howl. The baby looks at them all, clenching his fists together and punching the air, simultaneously bewildered and disgusted that he should have been placed in such an undignified situation.

Andrew finds it rather gratifying to witness this unexpected streak of stubbornness developing in his son’s character. But Caroline, her face pale, immediately lurches forward from the pew, hand outstretched as though she fully intends to take her child back. Andrew grips her arm to stop her. ‘It’s fine,’ he murmurs in her ear. There is a silvery thread of sweat in the dimple of her chin. She has been panicky since Max’s birth, more than usually anxious. ‘He’s fine. Leave him be.’

Caroline does not acknowledge him, but shifts away to one side, releasing her arm from Andrew’s grasp. She sits perfectly still and Andrew is left feeling that he has done something wrong, that he is being reproached by her, silently. But then, when they stand to sing the next hymn, she turns and smiles at him and mouths ‘Thank you’ and the natural equilibrium between them is restored. He puts his arm round her waist, lightly, to let her know he loves her.

But the organist is thumping out the notes too loudly and a headache that has been plaguing him since morning thuds insistently back into life, pricking the tightness behind his eyes, so that by the time the small congregation emerges, blinking, into the midday light, Andrew feels untethered from the ground, as though he is viewing proceedings through a pool of shallow water, his ears muffled so that everyone’s speech sounds disjointed and slow.

He removes his sunglasses from his jacket pocket and slips them on. The crispness of the autumnal daylight is immediately softened by an overlay of sepia. He looks around and sees Caroline, standing underneath the spreading branches of a sycamore tree just in front of a cluster of faded and slanting gravestones. She is laughing, relieved to have her son back in her arms, able now to joke about the timing of his tears.

‘Typical,’ he hears her saying to the vicar. ‘He’s been good as gold all morning and then just at the moment . . .’

Good as gold, thinks Andrew. She never used to speak like that. It amuses him, this habit she has of picking up phrases like a magpie picks up glitter. She tries so hard to be someone else, something better and yet Andrew loves her exactly as she is. It doesn’t matter how much he tells her this. She has no faith in herself, he thinks as he walks towards her. No faith at all. ‘Happens all the time,’ the vicar is chuckling amiably. ‘I seem to have that effect on babies.’ His mother is standing next to the vicar in a smartly tailored two-piece suit in royal blue. She laughs, causing the feathers on her fascinator to tremble. ‘Our son was just the same,’ Elsa says. ‘You should have heard the fuss that Andrew made. Of course, he’s been compensating ever since by being so terribly sensible.’

Caroline giggles, arching her eyebrows to show she knows exactly what her mother-in-law means, that she gets the joke.

Andrew edges into the circle of conversation, giving a non-committal smile. He holds out his arms to take Max, overtaken by the need to hold him, to feel him close.

‘Are you all right?’ Caroline asks and he sees that instead of giving him the child, she has moved to one side so that Max’s face is obscured by the folds of her blouse, the silhouette of her hip.

‘Fine, fine,’ he says, putting his hands back into his pockets. ‘Just a bit of a headache.’

Elsa looks at him. Her face, still beautiful through the wrinkles, is impeccably made up: blended brushstrokes of crimson lipstick, brown-black mascara, grey eyeshadow at the corners of her lids, lighter brown on the inside. She smells lightly of tuberose. ‘Have you taken anything for it?’

He nods. Elsa pats him on the arm. ‘Some champagne will do you good,’ she says. ‘When we get back, you’ll sit down and I’ll bring you an ice-cold glass of fizz.’

He sees Caroline frowning and then he remembers: they haven’t bought any champagne. Caroline had thought sherry would be more ‘appropriate’.

‘But first, I insist on having a cuddle with my glorious grandson,’ Elsa is saying, moving towards Caroline with elegant arms outstretched, a discreet gold bracelet hanging from her left wrist. ‘Oh I could just eat him alive.’

The vicar gives a giant guffaw, arching his back so that his stomach protrudes over his waistband. ‘Grandparents have the best of both worlds, don’t they?’ he says. ‘They can always give the little blighters back at the end of the day!’

The vicar carries on talking, but Andrew is not listening. He is looking, instead, at the interaction between his mother and his wife. Elsa still has her arms outstretched, is still waiting for her grandson to be handed over. Perhaps it is the headache that makes it seem such an interminable wait, as though the ticking of time has slowed down until it is more pause than motion. But it seems to him as though Elsa waits for several long minutes, her arms gradually sagging and falling back down to her sides when she finally realises Caroline is not going to pass the baby over.