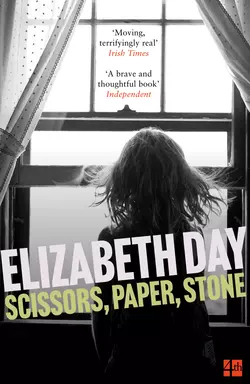

Scissors, Paper, Stone

Elizabeth Day

A frank and beautiful story of damage, survival and restoration from an exhilarating literary voice.As Charles Redfern lies motionless in hospital, his wife Anne and daughter Charlotte are forced to confront their relationships with him – and with each other. Anne, once beautiful and clever, has paled in the shadow of her husband's dominance. Charlotte, meanwhile, is battling with her own inner darkness and is desperate to prevent her relationship with her not-yet-divorced lover from disintegrating.As the full truth of Charles's hold over them is brought to light, both women must reconcile themselves with the choices they have made, the secrets they have kept, and the uncertain future that now lies ahead of them.

Scissors, Paper, Stone

Elizabeth Day

Copyright (#ulink_57b80b4b-8035-582a-bfa8-24fdc83d009a)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc in 2011

This eBook edition published by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © Elizabeth Day, 2011

Elizabeth Day asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008221775

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008221782

Version: 2018-03-06

Praise for Scissors, Paper, Stone (#ulink_4d8d5d44-7dd3-52d4-a54c-b53431dfe97d)

‘Elizabeth Day’s observations of a certain sort of middle-class life […] are altogether brilliant … Moreover, the self-restraint of the plot is as impressive as that of the characterisation: when the cause of the family’s unhappiness is finally revealed, it is all the more unpleasant for being so utterly unexpected’ Spectator

‘[A] tense, sensitive exploration of a mother and daughter's fractured relationship and the man between them’ Marie Claire

‘Deftly unpicks a daughter’s troubled relationship with her mother after her father has lapsed into a coma’ Observer

‘[Scissors, Paper, Stone] has the page-turning compulsion of a thriller combined with the horror of discovering exactly what happens when human behaviour skids from normal to disturbing’ Belfast Telegraph Morning

‘Rips along convincingly … Day reveals the horrible truth behind this ostensibly ordinary family. At this point Day's brilliance as a writer starts delivering a real punch … thoroughly believable’ New Zealand Herald

‘Clever and well-written’ Times Literary Supplement

‘Elizabeth Day has written an absorbing and moving novel in which she has managed to convey the chronic damage that a father, wife and daughter may do to one another. Her writing is both delicate and direct, not an easy combination to effect, but she has pulled it off’ Elizabeth Jane Howard

'A daring, absorbing and beautifully-written story of damage and betrayal, this is an exhilarating and deeply affecting first novel’ Jennie Rooney, author of Inside the Whale

To my parents,

for being nothing like Anne and Charles

Contents

Cover (#u3cb79802-9f70-53a8-997a-b36da8086986)

Title Page (#u6529dd63-d934-5322-ba61-acc1ed3faba3)

Copyright (#u5f4dbfe2-e06b-5e6c-9318-faf0b571bebe)

Praise for Scissors, Paper, Stone (#uf7098094-12a9-52e3-bdd0-0356cca5ba07)

Dedication (#u569e9445-8f74-5cdd-8e24-62b0021d4ec5)

Prologue (#ud75b1d66-e8e8-587d-b471-9ae19814ec74)

PART I (#uecbfee81-acf8-5e21-8ba8-e91b5035989d)

Anne (#ua33bfec0-2629-5ee8-a4fa-6581a2b76071)

Anne; Charles (#u71a14aff-cc95-57dd-80bd-2e07864eb903)

Charlotte (#u3ec1a7f1-c49e-5d93-bb86-e37d77a7d468)

Anne (#ud1886dd8-2cba-5175-9e28-2549e0a2e9f6)

Anne; Charles (#u355e849a-2cf1-5f36-b2ef-7f5b9bc2fc29)

Charlotte (#u4b523ace-e3d3-56ea-9383-7b980052e84f)

Anne; Charlotte (#u28d91224-7fa0-52f2-b361-2b82537f132c)

Anne; Charles (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Janet; Anne (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne; Charles (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne; Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne; Charles (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne; Charles (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Anne (#litres_trial_promo)

Charles (#litres_trial_promo)

Janet (#litres_trial_promo)

Janet; Anne; Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Janet (#litres_trial_promo)

Charlotte (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

A Note on the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_c0070a55-459d-535a-be33-f7205e6e0b3a)

At first he does not realise he is bleeding. He wakes in a state of numbness, with no memory of where he is. It takes him several minutes to notice the glutinous dark-red liquid but, even then, he cannot work out where it is coming from. It trickles past his nose with a slow insistence and gathers in a small pool at the tip of his finger. It smells of uncooked meat.

He can make no sense of his position. He appears to be lying on hard grey flagstones, his face parallel with the serrated metal surface of a manhole cover. His left cheek is pressed painfully against the pavement and he cannot open one eye. The other eye, sticky and blurred, is focusing on a blackened blob of chewing gum, trodden into the ground a few inches from his nose.

He rolls his eye around frantically in its socket, straining to see as much as possible. Out of one corner, he can make out the bridge of his nose. An arm is spread out underneath his head, disjointed and bent out of shape. He wonders briefly whose arm it is and then he works out with a jolt that it must be his and a sickness rises up inside him.

He finds that he cannot move. It is not that he feels any pain, simply that any physical exertion is impossible. Something is loose and rattling in his mouth. He presses at it with the tip of his swollen tongue and thinks it must be a tooth.

A voice that he does not recognise, male and throaty, is speaking. After a few seconds, he notices that the words make sense.

‘All right mate, all right, just keep still. The ambulance will be here soon.’

That is when he realises he must be bleeding. Instantly, he feels a desperate surge of white-hot panic. His one eye starts to weep, silently, and the tears drip down from the corner of his eyelid to the tip of his nose and on to the pavement, where they mix in with the blood, thinning it to a watery consistency. He tries to speak but no sound emerges. His mind is filling with infinite questions, each one expanding to fill the space like a sea anenome unfurling underwater.

What is happening?

Where am I?

What am I doing here?

He feels himself at the brink of something, as if he is about to fall a very long distance. He is overwhelmingly tired and his eyelid starts to droop, obscuring his field of vision even more. From the squinted sliver of sight that remains, he sees the rounded edge of a black leather boot. The boot is battered and laced and has a thick rubber sole and it is coming towards him and now it is treading into the redness that seems to be covering a larger area of pavement than before. As the boot moves away, he notices that it leaves an imprint on the ground, a stencilled trail of wet blood.

He can make out snippets of a conversation that is taking place above his head.

‘Yeah, he was knocked off his bike, poor sod.’

‘Christ. Was he wearing a helmet?’

‘Don’t think so. Driver didn’t even stop.’

‘Where’s the ambulance?’

‘On its way.’

His eyelid is pressing down, and despite telling himself that he must stay awake, that it is important to remain alert, he is powerless to stop it. Soon, he is enveloped by a throbbing darkness, a beating tide of black that crashes against the bones of his skull. He hears the sirens and, just before he allows himself to fall into nothingness, he has one startlingly clear vision of his daughter. She is twelve years old and lying in bed with the flu and he has made her buttered toast and she is too hot so she has drawn back the bedsheets.

The last thing he sees before his mind collapses is the precise curve of the pale flesh of her kneecap and he is saturated by love.

It was a curious thing, but when she was told that her husband was almost dead, her first thought was not for him but for the beef casserole. She had been in the process of boiling up a stock when the doorbell rang, tearing up parsley stalks and rummaging blindly in the cupboard for an elusive box of bay leaves. She answered the door while still wearing her apron and her hands were slightly damp as she unlocked the safety chain. A speck of indeterminate green foliage had attached itself to the cuff of her floral printed blouse. She was attempting to swat it away when she became aware of the uniformed officers on her doorstep.

There were two of them – a white man and a pretty Asian woman, standing shoulder to shoulder underneath the porch awning as though their primary purpose was to advertise the police force’s ethnically diverse recruiting practice. Anne braced herself to receive a fistful of glossy leaflets and a promotional plastic keyring, but then she noticed that neither of them was smiling.

‘Mrs Redfern?’ the man said, and the silver numbers on his epaulettes glinted in the mid-morning light.

‘Yes.’

‘It’s about your husband.’ He had flabby pink cheeks and small, round eyes and a kindness that hung loosely around his lips. He looked as though he should be outdoors, building dry-stone walls and eating thick ham sandwiches. Anne felt a twinge of sympathy for him, for how difficult he was finding it to enunciate the words. There was a short pause that Anne realised she was expected to fill.

‘Yes?’

‘I’m afraid there’s been an accident.’

She felt a coolness seep into her bones but she stood straight-backed in the doorway and did not move. The policeman looked relieved that she was not breaking down. The pretty Asian woman reached out to touch her arm. Anne became aware of the pressure of her hand and although she usually disliked the tactile presumption of strangers, she found it oddly comforting.

The man was talking, telling her something about Charles being knocked off his bicycle and being taken to hospital and the fact that he was unconscious: still alive, but only just.

Only just. She found herself thinking how strange it was that two small words could encapsulate so much.

Then the woman was talking about cups of tea and lifts to the hospital and is-there-anyone-you-could-call and Anne found that she was not thinking of Charles, of what state he might be in or of how worried she should be, but that instead her mind was filled with the perfectly clear image of four unpeeled carrots that she had left draining in a colander in the sink.

She told the police officers that she would drive herself to hospital.

‘Are you sure?’ the man asked, eyebrows pushed together in furrowed concern.

She nodded and added a smile for good measure.

‘Perhaps you’d like us to come inside and sit with you for a bit?’ said the woman, her eyes darting beyond Anne’s shoulder into the hallway.

‘No, honestly, I’ll be fine,’ Anne said firmly. ‘Thank you,’ and she started to close the door before they could say anything else. The casserole. She had to finish the casserole.

As she walked back through to the kitchen, she passed the ugly dark wooden hat-stand at the foot of the staircase. Charles had brought it home with him one evening several years ago, with no explanation. When she asked where it was from, he replied coldly that a colleague had wanted to get rid of it. She had known, by the tone of his voice, not to push the point any further.

The hat-stand struck Anne as a particularly useless piece of clutter, but it had taken up permanent residence in the hallway, casting grotesque shadows over the tiles like a stunted tree, its branches gnarled and misshapen into arthritic wooden fingers.

She had grown used to it and normally never gave it a second glance. But this time she noticed that Charles’s cycling helmet was still hanging on one of the lower hooks. She winced. A sudden vision of his bloodied skull, squashed and bruised like overripe red fruit, rose unbidden in her mind. She pushed the thought back under and returned to the chopping board.

For twenty minutes, Anne peeled carrots and diced potatoes and roughly sliced the marbled red beef that was springy and cool to the touch. When she lifted away the polythene bag in which the butcher had wrapped the meat, it left a trickle of bloodied water on the metallic indentations of the sink. Anne shuddered when she noticed, wiping it away briskly with a cloth.

She slid all the ingredients into a big saucepan, angling the chopping board at its lip and pushing the vegetables into the simmering stock with the back of the knife. She left it to boil and then she took off her apron and went upstairs and brushed her hair, tucking it neatly behind her ears. She unbuttoned the floral blouse and changed into a loose-fitting V-neck scented with the ferric freshness of fabric conditioner.

She was conscious of the fact that she was behaving oddly and she wondered for a moment whether she might be suffering from shock. But Anne did not feel shocked. She felt – what exactly? She felt cocooned, un-tethered from actuality. She felt vaguely anxious, but there was an underlying sense that nothing was quite happening as it should. It was not so much unreal as hyper-real, as if she had just been made aware of each tiny dot of colour that made up every solid object she looked at. It felt like the pins and needles sensation she got in the tips of her fingers after she warmed her cold hands against a hot radiator, only then becoming aware of the completeness of her physical presence.

The smell of the casserole wafted up from the kitchen, steamed and earthy. Anne walked downstairs, taking her time, placing each foot carefully in front of the other. She was conscious of the need for extreme caution because, whatever happened when she got to the hospital, she would need somehow to deal with it and she wanted to stretch out this small scrap of leftover time as long as she could. This, now, here: this was still the time before, the space that existed prior to knowledge. She had no idea yet what would be required of her or how badly Charles was hurt.

She could not work out how much she cared. She found that, given everything that had happened during their years together, she was not unduly upset by the thought of his death but then, almost simultaneously, she felt a bottomless nausea when she allowed herself the rapid shiver of contemplation of her life without him.

But she did not have to face him until she got there.

So she would finish making the casserole and then she would get into her car and drive to the hospital and from then on, her life would be different in some way that she could not yet fathom.

But not just yet.

The saucepan bubbled, the lid clattering gently against its sides.

Her mother’s name flashes up on her mobile.

‘Mum?’

‘Can you talk?’

‘Yes.’

She knows immediately that something is wrong.

‘It’s Charles . . . I mean, it’s Dad. Daddy.’

All at once, she is sick with anticipation. A desperate calm settles itself around her heart. For a second, she thinks her father is dead. The certainty of it filters through her skin, leaving a trail of goosebumps along one arm. A coolness tightens around her shoulders.

‘Oh God, no. No.’

She hears her voice begin to shudder. A gasping, dry sob rises in the back of her throat.

‘It’s all right,’ her mother is saying on the other end of the line. ‘Listen to me. He’s OK. He’s alive.’

She hears the words but does not, at first, understand them. She lets them slot into place, slowly reforming the sentence in her mind.

Not dead.

Alive.

Still living; still part of her.

And then, she no longer knows what to feel.

PART I (#ulink_49c43fbf-3ac9-5ebe-917e-917ea91a731f)

Anne (#ulink_966c10ab-8443-5391-9661-e0a78eb81b87)

When Anne was a child and her parents returned late at night from a party, she liked to pretend to be asleep. It was partly because she knew the babysitter had let her stay up longer than she should but it was also because she enjoyed the feeling of play-acting, of feigning something, of playing a trick on adults.

She would hear their footsteps on the stairs, the heavy and deliberate murmur of drunken whispers and half-giggles, and she would flick the switch of her bedside lamp and shut her eyes tightly, drawing the blankets up around her. Her parents would approach her bedroom and halt for a moment outside, shushing each other with exaggerated seriousness, before pushing open the door and poking their heads round. Her mother’s voice would say her name softly, each movement punctuated by the tinny jangle of earrings and bracelets.

Her mother would tiptoe over to the side of the mattress and lower her head to kiss her daughter gently on the cheek, and Anne, her senses heightened by the darkness, would feel the dryness of face powder and the creamy texture of her lipstick and inhale the thrilling adult tang of smoke and drink. Still, she would not open her eyes. Her parents must have known that she was awake but they played along. It became a harmless childhood lie.

She thinks of this now as she looks at her husband, lying on his hospital bed, attached to various tubes and drips. It looks like a pretence, this enforced sleep. His chest rises and falls. His eyes are closed. His mouth is turned down at the corners and over the last few days stubble has appeared on the pale folds of his face, like bracken stealing across a hillside. The sleep doesn’t seem at all convincing. It looks as if he’s trying too hard. Occasionally, his left eyelid will flicker slightly, a tiny electronic pulse emitted from some unidentified synapse.

She knows the facts. She has been told by the doctors that he is in a coma and she has nodded and been serious and given the reliable impression of a woman in her mid-fifties who understands what is expected of her. She has taken care of things, informed people, she has been calm and logical on the phone when issuing necessary instructions. She has been to the police station to pick up his bicycle, eerily unmarked by the accident, its metal frame sleek and grey and cool to the touch. She has packed bags and tidied and filled in forms and arranged for his transfer to a private hospital covered by his insurance. She has frozen the beef casserole. She has carried on, knowing that this is what everyone wants her to do.

But there is a secret part of her that thinks it is a colossal joke and that this isn’t actually happening at all. Her husband is lying in front of her, pretending to be asleep and he is once again the centre of attention, just as he always managed to be when he was awake. She knows he is pretending; he is misleading her into believing in something that does not exist. Well, she thinks to herself, I’m not going to be fooled this time.

And then, looking at his prone body, she becomes all at once aware of her own absurdity. She is shocked at her casual dismissal of her husband’s condition. She tries to think fondly of him, to remember some affectionate exchange they might have had in recent days. But instead all she can remember is the last conversation they had, just before Charles walked out of the door, dressed in his high-visibility cycling jacket, the zip undone so that the sides of it flapped in the breeze as he went.

He had not told her where he was going, and when she had asked, he did not lift his head to acknowledge that he had heard her. Instead, he carried on sipping his mug of breakfast tea in a succession of noisy slurps.

‘Charles?’

He raised his eyes to meet hers with familiar indifference.

‘Yes?’

‘I just wondered where you were going,’ Anne said a second time, hearing the meekness in her voice, the whining undertone, and hating it.

He put down his mug of tea with a quiet force. The mug gave a thunking sound as it made contact with the table and some of the liquid splattered on to the pale pine. Anne stared at the thin rivulets of brown, trying not to make eye contact with him.

‘Why would that possibly concern you?’ he said, his voice perfectly level. That would probably have been the end of it, but Anne had taken a dishcloth and started to wipe away the spilled tea and something in Charles had seemed to crack. No one else would have noticed it, but for Anne the change was immediately visible: a darkening of his pupils, a deliberate relaxing of the shoulders like a boxer priming himself for the ring, the ever-so-slight whistling sound of breath through his nostrils.

After a moment he spoke, his voice carefully modulated, as if holding itself back.

‘Do you know what I think of you?’ he asked, and although the question seemed out of place amid the mundane to-ing and fro-ing of the morning, Anne knew that he would have a reason for it.

She kept silent, balling up her hands into tight fists so that she could feel her fingernails digging into her palms. She concentrated on the discomfort of it, on the effort of marking her skin to prove she existed. When she relaxed her hands, there would be a row of sharply delineated crescents pock-marked across the tender pink flesh.

Charles was staring at her, his eyes stained with contempt, his head tilted in a quizzical pose. ‘Well?’ he asked, slowly, as if speaking to a stupid child.

Anne felt each muscle tense and prick against her flesh. She knew she had to answer or there would be no end to it. ‘No,’ she said and she could feel her voice disappear almost as soon as it hit the air, evaporating into wisps of nothing. She stood still, braced and alert for what would come next, the damp cloth cupped in her hand.

Charles coughed gently, a balled-up hand in front of his mouth. He looked at her and his eyes seemed dulled, like the dustiness on a window-pane when it caught the light. When he spoke, his tone was unchanged, innocuous, smooth like wax. ‘You disgust me,’ he said, so softly it was almost a whisper, and she wondered, once again, if she were in fact going mad. ‘Just looking at you, at your dishcloths and your dirty aprons, at your pathetic face. Just listening to you, your incessant whining, your pleading, snivelling voice asking me pointless questions.’ He paused to take a sip of tea and for a moment Anne thought he might have finished, but just as she was about to turn away, he put the mug down with exaggerated caution and continued. ‘You.’ He jabbed a finger at her. ‘You. You, with your tired eyes and your wrinkles and your housewifely flab spilling over at the sides and your thin lips and –’ He broke off and shook his head, as if disbelieving. ‘You used to be so beautiful.’

Anne went to the sink and busied herself with the taps so that she did not have to look at him. She felt herself about to cry and wondered why he still possessed the capacity to wound her so deeply. She had become accustomed to his bouts of callousness, to the random outbursts of his bristling, restrained fury. Surely she should be inured to it by now, should be able to sweep his cruelties aside? Why did she not simply walk out of the kitchen? Why did she not walk out of the house, out of this man’s life for good? Why did she stand here, bound to him, receiving each verbal blow as though she deserved it?

There was something that kept her here, a silken thread that tied her to him, that twisted around her wrists, her ankles, her chest, so tightly she could not move.

She found herself thinking about her youth, her dried-up beauty and the effortless slenderness that Charles had prized so highly. Once, in the very early days when they had been in bed together, he had lifted her skinny arm up to the light so that the delicate webbed skin between her fingers glowed like oyster shell held against the sun.

‘Almost translucent,’ he had said, before dropping her arm softly back on to the sheets and turning away from her. And she remembers now how happy she had felt with that small, dispassionate compliment. Had she really asked for so little?

But that had been years ago: a different woman in a different time. When she looked round from the sink, her vision blurred with the imprecise fuzziness of tears, she saw that Charles had gone.

The nurse comes in to check on the drip and smiles at her with a brisk nod of the head, just as they do in hospital dramas. It adds to her notion of play-acting. Of course, she thinks, the nurse is in on it too. He has somehow paid off the entire hospital to go along with this joke of his. How typical, she thinks, that he would go to such lengths to make her feel so beholden to him. She feels a familiar surge in the pit of her stomach, a pang somewhere between hunger and pain that she recognises as the beginnings of a small but lethal rage.

She has got used to these sudden, inexplicable bouts of anger and now barely notices them until they have subsided. She seems to be able to swing from extreme sadness and self-pity one minute to uncontained fury the next. Recently, at the wedding of a friend’s daughter, she was given a sparkler from a packet and told to light it and hold it aloft as the happy couple left for their honeymoon.

‘It’s instead of confetti,’ said the mother of the bride, an officious woman who prided herself on her organisational skills.

‘Oh,’ said Anne, realising she was meant to be impressed. ‘How . . . inventive.’

The sparkler burned quickly, throwing out bright shards of flame like dandelion spores. The guests whooped and waved until it all seemed a curious facsimile of joy, and then the mother of the bride started ushering people into taxis and Anne was left with the sparkler in her hand, a limp, ashen strip that smelled lightly of sulphur. It struck her then, after too much champagne, that this is what happened to her inside when she felt that heated explosion of intense disappointment. It burned bright, and then it burned out, and no one ever knew.

She had wanted to talk to someone about this, about the feeling that her life was gradually draining itself of purpose, revolving around the same dull axes, but she could no longer share such intimacies with Charles and her limited scattering of dull suburban friends would have been shocked by her honesty. Until Charles’s accident, she had felt oppressed by the cyclical nature of her days, as though she were stuck on a roundabout in an anonymous provincial town like the outer fringes of Swindon or a place called Blandford Forum that she had been to once with Charles; a town that had sounded vaguely Roman and exotic but that turned out to be full of grubby teashops and Argos outlets.

The worst of it was that it had all been entirely her doing. She had loved Charles, loved him completely, and probably still did in spite of no longer wanting to. But instead of giving her the contentedness she had once craved, her life with Charles has left Anne with a perpetual restlessness. She finds fault with everything. She picks at the stitches of each day with a relentlessness that leaves the seams frayed and the material torn out of shape. She does not understand happiness any more, cannot remember where to look for it, as if it is something she has mislaid – a coin that has slipped down the back of a sofa. She cannot remember the last time she laughed. She feels her core has been chipped away like marble. She no longer likes herself very much and can feel herself being ground down by her own defensiveness. She wishes she could be different, but it somehow seems too much effort to try.

She hadn’t always been like this. When her mother died last year after a prolonged descent into blindness and infirmity, Anne had sorted through the overstuffed little retirement flat and come across an enormous cache of family letters. Sifting through the postcards of long-ago mountainsides and the browning edges of airmail envelopes, she had discovered a series of letters written while she was at boarding school. Each of them was so funny, covered with illustrations and jokes and witty imprecations not to forget to make her favourite flapjacks for the holidays. She had been stunned to meet this youthful version of herself: so effortlessly full of character, so unaffectedly joyful, so naively sure of who she was. There were so many exclamation marks. She never thought in exclamations any more.

The asthmatic, mechanical, barely-there sound of her husband’s breathing interrupts her thoughts. He is still a handsome man, she thinks, looking at the clear, pronounced angle of his jawbone jutting out from beneath his earlobe as if welded in place. The skin around his eyes has been marked by a series of fine, engraved wrinkles in the last few years, but the crow’s feet suit him; give him an approachable air of bonhomie and sunkissed good health. His eyes look like crinkles of paper, twisted at the ends like packets of picnic salt. His lids are closed now, occasionally twitching as if a small bird’s heart is thumping delicately just below the surface of his face. But when they were open, his eyes were the bruised blue of faded hydrangea petals: flat, pale, remote.

The door opens and a nurse – the nice one with the dimpled smile – peers round the door. ‘Cup of tea, Anne?’

She nods her head, just as she is supposed to.

Anne; Charles (#ulink_a2227a92-54cc-5ed6-a421-5137151d4a07)

Charles Redfern was what her mother called ‘a catch’. She spotted him on the first day of lectures, sitting at the back in a tangle of splayed-out limbs and slumped shoulders. He raised his head briefly when she walked into the auditorium and she just had time to make out the arch of his eyebrows, peaking like precisely pitched tents, before his attention turned back to the well-thumbed paperback in his hands.

She couldn’t read the title. She found out later, much later, that it had been James Joyce’s Ulysses, a book that Charles had never read in its entirety, always giving up about a third of the way through the second chapter. But he liked to carry it around with him in those first few weeks of university in order to cultivate an impression of enigmatic intelligence; an aloofness that he thought made him both attractive and indefinable.

He was right, of course. Almost every girl had a crush on Charles Redfern by the end of freshers’ week. There would be a gentle buzz of whispered giggles when he walked down the corridor. Girls pressed their noses to the glass when he jogged past their windows on the way to an early morning training session by the river for the college rowing team. He was reported to have a girlfriend at secretarial college whom someone had once met at a hunt ball and who was believed to be astonishingly glamorous with unparalleled taste in clothes.

His was the type of beauty that lost all its originality in description. He was broad-shouldered and tall and possessed of a disarming smile that crept slowly over one side of his face when he was about to laugh. His hair was the gold of hard-boiled caramel. Once, a friend back home had asked her to describe his profile and she thought immediately of him lying next to her in the hazy light of early morning.

‘He’s like a Greek god,’ she said, totally serious.

‘What kind of answer’s that?’ shrieked her friend. ‘A Greek god? You’ve got it bad.’

‘Honestly. I think he’s the most handsome man I’ve ever met.’

‘And he’s your boyfriend? Well, I think you’re awfully lucky.’

The friendship hadn’t lasted much longer after that. There was something about Charles that made her both defensive and perpetually insecure – she feared never living up to his physical superiority, never being interesting or charming enough to keep his attention, as if his eyes would always drop, after a few seconds, back to a paperback he would never read all the way through.

But – miraculously, it seemed – he claimed to be smitten with her. He started seeking her out after that first lecture, turning up at odd intervals in the porter’s lodge of her college, a scuffed leather satchel slung across his shoulder. He would be there when she went for coffee on campus, sitting at a corner table with a group of boys in rugby shirts laughing raucously and throwing the occasional, level glance in her direction. He was there, standing in between the bookshelves of the university library, his unmistakable silhouette casting its shadow over the dusty spines. He was there at a cocktail party thrown by the German Society, an event she had gone to under duress from Frieda, her friend at the time. Frieda was a self-consciously dramatic Modern Languages student who believed that men her own age were all hopelessly immature and sought out the companionship of graduate students or professors wherever she could.

‘Come along,’ said Frieda, in that curiously mocking way she had. ‘You never know who you might meet.’

So she had gone because Frieda was too forceful to refuse. As a bribe, Frieda had lent her a greeny-blue shift dress, beautifully tailored from a length of raw silk inherited from her Parisian grandmother. It was the sort of material that was rough to the touch, yet glistened as smooth as an oil slick in the evening light. She was delighted with it.

‘It suits you,’ said Frieda. ‘I am too flat-chested to carry it off.’

‘Nonsense,’ she said, unsure whether to be offended or complimented. ‘Oh, I love it. Thanks so much for lending it to me.’

‘Pleasure. I’m glad it’s getting some use.’ Frieda stopped at the mirror above the basin in the corner of her room where she had been applying her make-up. She let the mascara wand hang in her hand in mid-air. ‘My grandmother went mad, you know. She ended up in a lunatic asylum, thinking she was Marie Antoinette.’

‘Oh,’ Anne said, because she wasn’t sure what else was expected. Frieda’s conversations were full of such brutal truths, buried strangely in the middle of a perfectly normal exchange. They would surprise her with their very matter-of-factness, their sudden bleakness bringing her up short and making her feel somehow frivolous, as if she had stubbed her toe against a half-concealed boulder.

Half an hour later, they set off, arm-in-arm, not quite intimate enough to be true friends and yet not antipathetic enough towards each other to bother much about this fact. She found that university was full of such thrown-together alliances. She planned to stay for an hour at most at the cocktail party, then walk back to her room and finish an essay that was bothering her.

As soon as they walked through the door, Frieda became engrossed in conversation with a lugubrious-looking professor who bounced up and down on his tiptoes every time he got excited. She, meanwhile, hung about on the fringes, feeling rather trivial. For some reason, as she had walked through the college gardens, she had been seized with the desire to pluck a bright purple bloom from the flowerbed and put it in her hair. Frieda had looked at her disapprovingly and she saw now that Frieda had been right: it was a studiedly whimsical gesture that all at once seemed out of place here, in this dark room, filled with earnest undergraduates in elbow-patched jackets and wire-rimmed spectacles. Along one wall, a long table was half-heartedly filled with two trays of damp mushroom vol-au-vents and bowls of Twiglets. Someone had tried to make a hedgehog shape with cocktail sticks of cubed cheese and pineapple, but the sticks appeared to be too heavily weighted, so that the display looked wilted. The desultory strains of an ana-chronistic harpsichord were emanating from a slim record player in the corner.

Anne hated clubs and groups and societies as a rule – had spent most of the first half of term avoiding enthusiastic recruiters for hockey teams or film appreciation discussions – and now here she was, feeling uncomfortable and cross with herself simply because she had been too weak to say no.

She was smiling listlessly, working herself into a gradual state of agitation, and then she turned round and Charles Redfern was suddenly in front of her, holding a bulbous champagne glass filled to the brim with a violently crimson liquid.

‘I want to take you out for a drink,’ he said, as simple as that.

‘You don’t even know me.’

‘I do. I know your name is Anne Eliott. I know you are a first-year History student at Newnham College, Cambridge. I know that you are approximately 5ft 6 and that you have –’ he broke off, leaned forwards and squinted intently at her face, ‘dark brown eyes flecked with green.’

‘They’re not flecked with green.’

‘Yes, they are. You should look at them some time.’

She couldn’t think of anything to say to that. He smiled, still looking straight at her, and she noticed that the smile didn’t quite reach his eyes but stopped at the bridge of his nose. Although she never usually blushed, she could sense an unfamiliar warmth creeping up from her clavicles to her face.

‘It’s much easier to say yes now. Otherwise, I’ll have to keep pursuing you and you’ll have to keep pretending to ignore me.’

‘How do you know I’m pretending?’

‘I don’t know . . . something about the tilt of your head. When you’re concentrating on a lecture, I’ve noticed that you sit very upright. And when you’re chatting to friends or whatever, your hair sort of bobs from side to side. But when you’re pretending not to notice me, it’s neither one nor the other. You stand very still and you stare very intently at something you’re meant to be concentrating on, but there’s a slight . . . well, I suppose it’s a tremble, for want of a better word.’

‘A tremble?’

‘Yes. Like when you pretend to be asleep, but other people can tell that you’re not. Like that.’

She couldn’t say anything much for several seconds and he just kept on looking at her, gravely and with such intensity she couldn’t help but think it meant something. He seemed irrevocably in control of the situation, silently directing its progress according to some plan he had already formulated and would not be diverted from. His calm, focused insistence was intimidating but also oddly flattering. She was disarmed by his attention.

Then, just as she was preparing to say, yes, take me for a drink, I’d like that, he smiled at her, lifted his right hand so that it was just level with her cheek and quickly, so quickly she wondered afterwards if it had actually happened, brushed a tendril of her hair behind her ear, letting his fingertip graze against the nape of her neck. She breathed in, sharply. Then he turned and walked away.

So then, inevitably, she was smitten too. A week later, she ran into him again in the library, sitting at one of the long wooden desks in the reading room, rolling a cigarette.

‘Hello, Charles.’

He looked up and a grin spread slowly across his face.

‘Anne Eliott,’ he said, licking the cigarette paper. ‘When are you going to come for that drink with me?’

They cycled to a pub in Grantchester on a windy, grey day with the flat, grassy meadows spreading out beneath them like wet brushstrokes. Swans dotted the riverbanks, patches of white set with angular elegance against the murky brown water. Charles led the way, with Anne following breathlessly behind. She looked at his back, the dip and rise of his shoulders as he cycled over the ruts and bumps of the path. She saw the way his hair was just long enough to be ruffled by the breeze. She noticed that he kept checking she was keeping up, head turning just far enough to catch her eye. It felt entirely as it should.

Later, after her half shandy, he kissed her briefly on the lips and said she tasted of sherbert. Later still, he took her back to Newnham and pushed her gently against the red brick wall, taking her face in his hands and, without speaking, kissing her lips, her cheeks, her eyelids. Then, because male visitors were not allowed to stay the night, he left and she went up to her room, tingling with the quiet fizz of joy.

When she took him home two months later her parents were predictably charmed.

‘Darling, he’s wonderful,’ her mother said in a theatrical whisper, almost as soon as her father had shown him upstairs to his room. ‘What a catch!’

At supper, Charles complimented Mrs Eliott on the perfect pinkness of the roast lamb, and her mother, suffused with pleasure, let the gravy boat slip in her hand so that it almost spilled its contents all over the embroidered linen tablecloth. He engaged Mr Eliott in a lengthy and considered conversation about the American civil rights movement without ever proffering an opinion that might have been deemed overly controversial or uncomfortably radical. He seemed a perfect cut-out of everything her boyfriend should be.

‘He’s a damned sound chap, Annie,’ her father said in the drawing room the next morning, folding away his newspaper and leaning forwards to stab at the fire with a long brass poker.

‘Archie!’ said her mother, whose unnecessary horror at her husband’s language had become a sort of fond family joke.

‘I’m only saying, darling. I like him. Like his drive. You could do a lot worse, you know.’

‘I’m sure Annie knows her own mind.’ Her mother lifted her dark-grey eyes from her sewing. ‘Don’t you, darling?’

She smiled. Yes, she did. She knew her mind. But, as she was about to find out, she couldn’t have claimed to know his.

Charlotte (#ulink_b2977762-ef9a-5e3a-a20d-e1fc641baf9f)

Charlotte was late again and although her lateness had an inevitability about it, this was never the comfort that it should have been. You’d imagine, she thought as she wove perilously in and out of the dense London traffic in her small blue car, that knowing I was going to be late would make me prepare more thoroughly in advance so that I would end up being on time. But she never quite managed the crucial leap between thought and action. Her lateness was now one of her defining features, an aspect of her personality that was gently tolerated and jovially referred to with affectionate exasperation by almost everyone who knew her. She had friends who would deliberately factor in a delay of half an hour when Charlotte arranged to meet them. But her mother was different: she could never be late for her.

She was dreading seeing her, a cold, dank dread that lay fetid and heavy across her chest. Recently, she found that she could not even pretend to relax in her mother’s presence: every time she saw her, the whole situation felt so stilted and unreal that their conversations had become defined more by the gaps between what was said than by the words themselves.

It had all stemmed from the time a few months ago when her mother turned up unannounced on the doorstep in the early morning. It was Charlotte’s thirtieth birthday, a date that she had been determined to ignore, and she recalled opening the door of her flat and being unable to disguise her horror. She had literally taken a step back, as if recoiling from her mother’s presence, attempting to get away from her.

‘Anything wrong?’ her mother said.

‘No!’ Charlotte replied, the forced jollity jarring in her ears.

‘Well. Good. Thought I’d surprise you. Happy birthday.’ And, still standing on the threshold, she had passed her a square, neatly wrapped package, the action appearing unnatural and false.

‘Thanks.’ Charlotte did not invite her in. She was still in her pyjamas, and her boyfriend, Gabriel, was splayed across the bed in a tumble of duvet and sheet. She became aware that she wanted to get rid of her mother as quickly as possible, for some reason she could not grasp. She hastily tore off the wrapping paper to reveal a shiny dark blue box with a small gold clip at one end. When Charlotte opened it, she saw a familiar silver ring, topped with a small, oval ruby set in diamonds.

‘Mum . . .’

‘I want you to have it.’

‘But, Mum,’ Charlotte felt sick. Her heart started thumping. ‘What are you doing?’

Her mother cleared her throat. ‘It doesn’t fit me any more.’ She smiled oddly. ‘Besides, who else would I give it to?’

‘It’s your engagement ring.’

‘Yes.’ And her mother had turned and let herself out of the front door without another word. There had been no time for Charlotte to say she didn’t want it.

She braked too suddenly at a set of traffic lights and her handbag fell off the front passenger seat, scattering a motley assortment of hair clips and old postage stamps into the footwell. A necklace with a broken clasp that she had been carrying in her bag for weeks had started to unravel and several tiny purple beads were rolling on to the fuzzy grey carpet. ‘Bugger,’ she said out loud, although there was no one else to hear her. She scrabbled around to put everything back inside and then the lights changed and the looming double-decker bus behind her started beeping its horn. ‘All right, All right.’

Thinking about her mother generally had this sort of effect on her. It wound her up, made her tense and simultaneously guilty for no real reason. She felt somehow responsible for her mother’s happiness and yet resentful that the burden weighed so heavily on her. She hated that she still cared enough to try to be the dutiful, supportive daughter. After all, Charlotte thought, her mother had never once said that she loved her. It wasn’t her way. Instead, she seemed perpetually disappointed: by Charlotte, by herself, by life and its accumulated disenchantments.

Her parents had never been ones for hugging or good-natured arguments around the dinner table or the rambunctious rough-and-tumble that characterised those large, semi-aristocratic families she was always reading about in period novels. There had, instead, been an unspoken friction, a constant and wordless atmosphere of slights perceived and grudges held.

Supper-times had been the worst. They would sit round the pine kitchen table, straight-backed and solicitous, with wariness in their eyes. Her father would speak first, his comments punctuated by the metronome click of his jaw as he chewed. What he said was never as bad as the way he said it. He would start off with a bland observation, usually aimed at her mother.

‘Another new top, I see.’

There would be a pause, pregnant with the electric possibility of disaster. Her mother would make a great show of looking down to see what she was wearing before assuming an unnatural informality.

‘Oh this? Yes, I bought it the other day . . .’ She trailed off, aware of his uncomfortable stare.

‘How . . . extravagant,’ he said, administering each word as if it were a drop of acid pressed from a chemist’s pipette.

‘Not really,’ her mother rallied quietly. ‘It was in the sale.’

‘Oh, I see.’ He gave a dry chuckle and wiped the corners of his mouth with the edge of a table-napkin. ‘You’re saving me money. Well, I suppose I should be grateful.’

Sometimes that would be the end of it. Sometimes her father would keep pushing and pushing until her mother would leave the table, sliding her chair back so abruptly that it would shriek discordantly against the tiled floor. On those occasions, Charlotte would be forced to stay at the table in silence until he had finished eating.

After the dinner plates had been cleared away, there would be no television because every single programme apart from the news appeared to annoy her father, darkening his moods until it seemed all the air had been squeezed to the corner of the rooms and pushed through the cracks in the walls. He would never shout, but the repressed fury of his controlled breathing was somehow worse than anything else.

The tension would be so unbearable, the need to apologise for whatever she was watching so constant in her mind, that the whole thing ended up being horribly unrelaxing. The only time she found she could watch television with impunity was just after she got home from school and just before her father returned from work, a golden period of two hours where she could sit herself on a beanbag in the front room with a slice of Battenberg cake and with the luxurious prospect of an uninterrupted session of Grange Hill and Blue Peter stretching out in front of her. Her ears were finely tuned into the precise sound of her father’s car engine. When she heard the first growling rumbles of his BMW, she would leap up, switch off the television and sprint upstairs, closing the door to her bedroom and opening her school exercise books so that she would not have to talk to him.

Sometimes, he would knock on her door on his way upstairs.

‘Charlotte?’ He waited until she replied before he pushed the door open, but even then he refused to walk over the thin metallic strip that separated the dark red hallway carpet from the light, beige tones of her bedroom floor. It always felt awkward, his standing there as if on sentry duty, casting his wordless eye over what she was doing.

‘Busy day?’ he asked.

‘Sort of,’ Charlotte said and then couldn’t think of anything else to add. She smiled at him as neutrally as she could. He stood looking at her in silence for a few seconds, loosening his tie with one hand.

‘Good,’ he said. He shifted on his feet, as if he were about to step forward and move closer to her. She saw this and instantly she felt her shoulders jolt backwards, a movement so slight it might not have happened, but he noticed and immediately he turned from her and walked out, making long strides towards the bathroom. After a few minutes, she heard the sound of running water.

She did not know if her family was normal or not. She had few friends to confide in. She was a very lonely child, scared of other children and terrified of new experiences. She had no siblings and was unsure how to relate to people her own age. There was nothing she hated more than her mother saying she must go to a party ‘because so-and-so’s daughter will be there and she’s the same age as you’. Or those horrifying dinners where her parents would sit on one table with the adults and all the children would be expected to gather round a shaky fold-out picnic table with novelty napkins and coloured paper crowns. ‘It’s more fun for them that way, isn’t it?’ the hostess would say, with a facile smile on her face, when actually everyone knew the only reason for their annexation was that the adults couldn’t be bothered to look after them.

It wasn’t ever more fun, thought Charlotte. As a rule, she found that most children regarded her with a naked distrust that soon turned into a virulent mutual loathing. The worst thing was getting stuck with a group of girls who were already, through a series of esoteric family connections, the firmest of friends. They would either gang up on her and whisper about her behind cupped hands, or she would try to be friendly to one of them and immediately be accused by another girl of ‘trying to take her away from me’. She never seemed to wear the right clothes or to have done the right things. Once, when she admitted she had never watched Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, a girl called Kitty with frizzy blonde hair and shiny lips said she was ‘odd’, which had seemed the cruellest possible insult at the time.

Instead, she revelled in isolation. At home, she would spend hours reading in the shed at the back of the garden, sandwiched between old deckchairs and the greasy oiliness of lawnmower spare parts. The shed was her favourite retreat. Sometimes, when things in the house got almost too much to bear, she would come to the shed and imagine that she had run away. She would sit for hours in between two coal sacks wondering if anyone had noticed that she was no longer there and then, when the floor got too hard and the night-time draughts started to seep through the cracks in the wood, she would be forced back inside and neither of her parents would remark on her absence. And it was this – the fact that they had not been worried about her – that used to upset her more than any unhappiness she might have felt in the first place.

‘Get out of the fucking way!’ she screamed as a moped screeched to a halt in front of her. She swerved just in time and saw the familiar outline of the London Bridge Hospital down a road to her left. She indicated, then remembered that the left light wasn’t working and she had yet to get it fixed. Her father had always told her she should do hand signals out of the window if this ever happened, but she was too embarrassed, so she took her chances when she saw a gap in the traffic.

The thought of him made her shiver.

Once inside the hospital car park, where a space was hardly ever available despite the outrageously high charges, she felt the familiar sense of unease settle like a shroud. She hated hospitals: the smell of disinfectant and surgical gloves, the squeaky linoleum, the endless corridors without windows, the collapsed grandmothers shuffling to the loo in their slippers, the enforced cheerfulness of the nurses that made everything seem so much more terrifying.

‘Deep breath,’ she said to herself. ‘You’re not the one who’s ill, after all.’ She picked up her battered handbag, put it over the crook in her arm and walked inside. The automatic glass doors whirred open into the reception area. Along one wall was an ersatz gift shop which sold newspapers (the Daily Express always went first, she had noticed) and sad-looking teddy bears with sickly purple bows tied round their necks. The lift pinged when she pressed the call button and she was soon on the fifth floor. She walked to the end of the hallway, pausing to squeeze a blob of alcohol on her hands from the anti-MRSA dispenser on the wall, and pushed the door on her right, sliding it slowly open.

‘Hello, Mum.’

Her mother was standing by the window, looking outwards to the indistinct greyness of the sky. She turned suddenly when Charlotte walked in. ‘Oh, hello,’ she replied absent-mindedly, as if she had not been expecting her.

‘How is he?’

‘Much the same,’ her mother said, her eyes obscured by the pair of pastel-framed bifocals she wore for reading. ‘The doctor says we should try to talk to him.’

Charlotte looked at the crumpled figure of her father, shrunken and pale against the hospital sheets. She felt unhappiness wash over her. The light in the room seemed to bleach at the edges, draining the room of colour so that everything became shaded in a matt greyness.

It was time to start acting the role that was expected of her. She pushed her shoulders back and smiled too brightly.

At the foot of the bed hung a thin wire basket in which was slotted a cheap blue ring binder containing his hospital notes. Above his head, on an easy-wipe noticeboard, a nurse had written hurriedly in red felt-tip: ‘Charles Redfern. 55 yrs’.

‘Hello, Dad.’

Anne (#ulink_19f5b019-ebf5-5b70-ba26-6f63a9c74049)

Anne loved her daughter so much it felt like a glass splinter lodged deep in her heart. Yet she found herself incapable of expressing it and this, more than anything else, seemed to drive them apart.

She was unaccountably cross that Charlotte was late. She had promised faithfully to be at the hospital at 6.30 p.m., but it was now 7.15 p.m. In that time, Anne had worked herself up into a state of highly pitched emotion that was a complicated knot of fury, fear and the suspicion that Charlotte simply didn’t care enough about her to turn up. The anger had crept up on Anne so imperceptibly that she had been unable to stop it leaking out in small but significant gestures; a succession of cold stares and raised eyebrows.

She knew that Charlotte picked up on it immediately, that her daughter sensed the tension in the atmosphere as soon as she walked in the room.

‘How was the traffic?’ Anne asked, trying to pepper her voice with lightness, but sensing in spite of herself the dried-up husks of her words.

‘Oh, pretty rubbish, you know. Rush hour. That kind of thing,’ Charlotte said abstractedly.

‘It’s terrible the traffic in London these days,’ Anne said, because nothing else came to mind. She gave a dry little cough. ‘What time did you leave work?’

Although Charlotte’s face remained perfectly immobile, Anne could see that the tendons in her neck were taut with some indeterminate strain. When she replied, her voice was prickly.

‘Normal time. Six-ish.’ She put her handbag down on the floor, shrugging herself out of her jacket. She sighed, audibly enough that Anne could not help but hear it. ‘You know, I didn’t mean to be late. It’s not deliberate.’

Anne said nothing. She hated it when Charlotte became irritable. She had wanted her to notice her obvious discontent but only because she had craved an affectionate, apologetic response. And now it was too late to backtrack.

‘Well,’ Anne heard herself say. ‘You’re here now.’

The air between them crackled.

Charlotte shook her head, so slightly that no one else but Anne would have seen it. But she noticed every tiny movement Charlotte made. It was her substitute for spoken intimacy. If nothing else, she could watch her. She could know her like a collector knows his butterflies: beautiful samples, pinned up in glass cases, wings outstretched so that every marking was clear. And by knowing her this way, by checking every nuance of her light and shade, by detailing each twitch and tremble, every gentle susurration of an unintended sigh, Anne could move as close to her as she dared. She gazed at Charlotte from a safe distance.

She was worried that she loved her daughter too greatly, that to reveal the extent of it would be to overwhelm the precarious balance of their relationship. She felt her emotions were calcified by guilt at not having been a good enough mother, a deep, unspoken, dug-away sort of shame that burrowed away inside like a creature with vicious teeth and claws. To let Charlotte see how much she cared, to be honest about her imperfect love, would be somehow to reveal this failing. Anne was scared at the thought of it.

They both knew where this guilt came from and Charles, when he had been awake, he had known too, but they never spoke of it. Instead, there was a triangulation of silence, a delicate construction of half-accepted ignorance that was as brittle as spun sugar.

Charlotte drew up a hospital chair to sit beside her father’s bed. She was close enough that, if she had wanted to, she could have touched him, but Anne saw that she stayed a little apart, in her own separate space. She did not take his hand.

Charlotte’s hair hung loose around her face, strands of wavy dark brown that were neither entirely straight nor tightly sprung enough to be curly. It annoyed her, Anne knew, that her hair could never be relied upon. She would use these dreadful hair straighteners each morning that seemed almost to frazzle her hair to a cinder. Sometimes Anne would notice she had burned herself on the top of her forehead, a small reddish imprint that no one else would see. In spite of the straighteners, Charlotte’s hair would always be crinkled by the end of the day. Anne preferred it like this, untampered, but she knew that her daughter hated its uncontrollable nature.

Her daughter was a pretty girl, not that she had ever told her this. But Anne knew it, objectively, because other people remarked on it when they saw her photo or when they first met her. She had an oval face and smooth skin with a faint splattering of freckles across the bridge of her nose. Her eyes were large and light blue and quizzical-looking. She had dainty earlobes, carefully defined and covered with soft downy hair that Anne stopped herself from reaching out to touch. Today, she was wearing earrings that looked like pieces of birch bark: silvery brown crescents that shivered when she spoke.

She was speaking to her father in a low, careful voice. The doctors had insisted that talking to Charles could have a positive effect on his recovery but Anne could not shake the unnaturalness of it; the slight embarrassment of a one-way conversation consisting almost entirely of the sort of mundane trivialities that Charles had always hated being subjected to. Listening to her daughter’s hesitations and forced jollities, Anne realised that Charlotte felt it too. It had never been particularly easy to talk to Charles. Now, it seemed almost impossible.

She tuned into what Charlotte was saying and realised she was talking about the holiday she had just been on with her boyfriend, a man Anne neither liked nor trusted.

‘. . . so then we went to this beautiful hilltop village and it took ages to walk up to the top because it was unbelievably steep.’ Charlotte broke off and poured a glass of water from the plastic jug on the bedside cabinet. She furrowed her brow, thinking of the best way to continue and then, before she started to speak again, Anne saw her quite deliberately force a smile on to her face. She wondered why she did this and then she realised that Charlotte’s words now sounded warmer as she spoke them, the curve of her lips shaping each sentence with a brightness that had not been there before.

‘When we finally got there, we were both so exhausted and sweaty that the first thing we did was find a nice outside table at this café on the square to drink a citron pressé and just look for a bit at the view. It really is the most lovely part of France – un-touristy, for some reason, I suppose because it’s not that close to the coast, but . . .’

‘Where was this?’ Anne asked a little too loudly.

Charlotte looked up, surprised and slightly flustered by the interruption. ‘Oh, it’s a region called the Tarn.’ She stopped and Anne waited for her to continue, just long enough that the silence started to feel scratchy. ‘I’d never heard of it, although it turns out that Claudia – you remember Claudia don’t you? – well, her parents have a house fifteen minutes from where we were staying, but I only found out when we got back, otherwise we would have dropped in.’

‘What’s Claudia doing with herself these days?’

‘She’s, um, she’s in banking. Something to do with hedge funds. I don’t really understand it.’

‘She was always such a nice girl. Very polite. I remember she wrote the most charming thank-you letters when she came to stay.’

‘Yes,’ Charlotte said, and Anne could see instantly from the vague wrinkle between her eyebrows that she thought she was being unfavourably compared.

‘Well, anyway, I’m sure your job is much more interesting.’

‘Mm-mm.’

And so the conversation juddered on, halting and uncomfortable and never entirely real, as if they were both reading from a bad script and neither of them knew what to do about it. And there was Charles, lying gloriously in the middle of it all like a stone figurine sculpted for the top of a medieval king’s tomb; static yet simultaneously alive, able to hear yet not listening, her husband, Charlotte’s father and yet, at the same time, neither of these things. Not really. Not now.

Later, as they stood outside the hospital doors saying their awkward goodbyes, Anne leaned forward and gave her daughter a half-peck on the cheek. She inhaled the fig-scented perfume that Charlotte always wore, taking a deep breath in and then holding it for a moment, like something precious and breakable, in the pit of her stomach.

‘Anyway,’ said Charlotte, pulling away, pushing up the shoulder strap of her leather bag that kept slipping down her arm. Her smile was pained, almost embarrassed. ‘See you.’

Charlotte turned and strode towards the car park, her silver birch earrings swinging as she walked. Anne watched her climb into the driving seat and for a brief moment their eyes met through the windscreen and both of them seemed surprised by this unexpected moment of recognition. Charlotte smiled and raised a hand. Anne nodded, more curtly than she’d intended.

Anne drove along the main roads to get back to Kew, past the fried chicken shops and the sari emporiums and the queues of tourists outside the London Dungeon and Southwark Cathedral, through the endless traffic lights that turned to red just as she approached them. It would have been quicker to go the back way but she felt the need for bright streetlamps and noise and urban chaos. It felt reassuring to see it all going on as usual, everyday life continuing undaunted beyond the hospital’s distillation of loss and hurt and illness.

Her mobile phone rang, the screen flashing up with a ghoulish light. It was Janet. ‘Oh no,’ Anne said out loud, fumbling to connect the hands-free set with one hand on the steering wheel. ‘Janet?’

‘Hello, Anne. Just calling to see how things went at the hospital today?’

It was typical of Janet to call at just the wrong moment, proffering just the wrong sort of concern – the kind that required exhaustive explanation and a decent show of emotion. Speaking to her always left one with a residual feeling of baseless unease, a sense of not having quite met up to the exacting standards of her goodness. She was so unremittingly nice it was impossible not to be irritated by her and yet simultaneously ashamed of this irritation. It made for draining conversations.

They had met years ago at the local Salvation Army Christmas carol concert, an event that Anne had found herself attending with dreary regularity in an attempt to paint herself as an upstanding and contented member of the community, a family-oriented mother and wife, a fund-raiser for assorted charities and a dedicated watcher of Antiques Roadshow. For a while, she had believed that pretending her life had some sort of meaning would actually give it some, as if the acting was half the effort.

Charles had never come along with her – he called himself an atheist and made a great show of shirking any sort of religious pomp – and this had been a relief, in a way. It allowed Anne to create an alternative persona: one of wholesome cake-baking goodness and jumble sales. She found a safety in this pretence, singing along heartily to rousing carols and contributing generously to the collection plate. She liked Christmas and discovered that seasonal festivity was the perfect opportunity for anonymity without isolation. Strangers smiled at her and caught her eye, but it was easy to elude conversation, to slip out just as the mulled wine was being poured.

That was until she met Janet. Janet had suddenly appeared one year, wreathed in jollity and home-knitted scarves, bearing Tupperware boxes filled with mince pies. She made a bee-line for Anne as soon as she spotted her trying to leave.

‘Sure I can’t tempt you?’ Janet asked, a beaming smile on her face. Anne looked at her and noticed the filmy eyes, perpetually on the brink of some extreme enthusiasm and the garish, orange-red lipstick beginning to bleed into tiny lines around her trembling mouth. She felt sorry for her, a small, unfamiliar twinge of empathy, a sense that Janet too was struggling to fit in, was desperate to find her own place in all of this communal bonhomie.

‘I was just on my way home, actually.’

‘Oh go on!’ Janet tinkled cheerily. ‘One mince pie won’t do any harm. I made them this morning. Grab one while you can.’

So Anne had taken a mince pie and the pastry had crumbled all over her coat and Janet had been so pathetically grateful that Anne stayed far longer than she wanted, trapped by the force field of Janet’s self-conscious jollity.

The friendship had stopped and started over the years, like a wheezy old car that struggled to accelerate up hills. But each time it threatened to extinguish itself completely, Janet had come up with some novel ruse to keep it going – free tickets to Chelsea Flower Show, a cake recipe she’d been dying to try out on someone, the chance to go to a lecture on Darwin’s evolutionary theory at the Natural History Museum, a new cheese shop that had just opened round the corner and was meant to stock the most fabulous Pecorino. And each time, Anne had capitulated – partly because it was easier that way and partly because, in spite of herself, she found Janet’s company strangely soothing. She never had to make any conversational effort in her presence and found it easy to let Janet’s cheerful monologues wash over her, smiling and nodding her head when it was required. She was, Anne supposed, her only real friend.

Once, but only once, Janet had stared at her across a café table and said, out of nowhere, ‘You never really listen to me, do you?’ Anne had protested unconvincingly and was mortified to see tears well up in Janet’s eyes. She couldn’t think of anything else to say, so she had lapsed into silence. After a while, the tears receded and Janet flapped her hands in front of her face. ‘Sorry. Ridiculous. Don’t know what’s wrong with me today.’ And that had been that.

This Friday, they had been due to go to Paris for the weekend – ‘A girls’ trip,’ Janet had said when they booked their Eurostar tickets – but now it all had to be cancelled. Janet was being purposely cheery about it, as if living up to her own notions of what a ‘trooper’ she was. She had insisted on dealing with all the paperwork, in enquiring about refunds and phoning up the hotel to let them know they would no longer be requiring two single rooms with en-suite showers. And then she had told Anne all about what she’d done, seeking approval with a single-mindedness that recalled a dog gripping a stick between its teeth. Anne knew that what Janet most wanted was someone to reassure her how selfless she was, how wonderful she’d been in a crisis, to say, ‘I don’t know what I’d do without you,’ and yet it was precisely because she was so needy, so oppressively grateful for any morsel of attention, that Anne found herself feeling perversely disinclined to play the game.

She knew this was mean and she was half-horrified by her own capability for small cruelties, but she couldn’t help herself. To an extent, her friendship with Janet enabled her to vent the frustrations accumulated in the rest of her life: it was the only situation she remained entirely in control of. For some reason, that was important.

‘You sound tired,’ Janet was saying now on the phone. ‘Was it a terribly draining day?’

‘No, no,’ said Anne. ‘It was fine.’ A mini-van stopped suddenly in front of her without warning. ‘Oh, bloody hell.’

‘Anne? Are you all right?’

‘Yes. Just a van driver who doesn’t know his highway code.’

Janet tittered on the end of the line. ‘So is there any update from the doctors?’

‘Much the same. They never really want to say anything in case they get sued. In any case, they’ve got to wait for the brain swelling to go down before they can be sure.’

‘Sure of what?’

‘Of whether there’s any permanent . . . well, you know, brain damage.’

There was a self-consciously dramatic intake of breath on the other end of the line.

‘They said that if he’d been wearing his bicycle helmet he might have walked away unscathed. I kept telling him to wear it,’ Anne said, rather pointlessly, she thought.

‘Are they any closer to finding out what happened?’

‘No. The police say there were no witnesses, which frankly I find hard to believe, but they never care much about cyclists, do they? The doctors think his bike was clipped by a passing car and he was thrown off. He was lucky to have landed on the road. If he had fallen into the path of a moving car, then it could have quite possibly been fatal. As it is . . . well, he’s in this coma.’

‘Goodness, Anne. How horrific.’

‘I suppose it’s just something we’ll have to deal with,’ Anne said, her impatience breaking through. ‘He might wake up tomorrow and be absolutely fine.’ She found she was unable to muster the requisite good cheer that this thought should have provoked.

‘I think you’re being a tower of strength, I really do.’

Anne stayed silent for a beat too long.

‘And you needn’t worry about Paris. Because we cancelled more than forty-eight hours in advance, the hotel has very kindly reimbursed our deposit, although it took quite a bit of doing, I tell you. My schoolgirl French isn’t what it used to be.’

Another tinkle of forced laughter.

‘Anyway, Anne, I should let you get on if you’re driving. Did you see Charlotte at the hospital?’

‘Yes, she came after work. Turned up late, obviously.’

‘Oh . . . well. That was nice of her to make the effort.’

‘Mmm,’ said Anne, non-committally. ‘I think she had a nice holiday in France with the man, although she never really tells me anything.’

‘Well, it’s a tricky one, isn’t it, Anne?’ Janet cleared her throat, preparing to take a leap into dangerous territory. ‘Perhaps she feels you might not approve.’

‘I don’t approve of him. He’s married, for goodness sake.’

‘I thought he was separated?’

‘Separated, maybe, but certainly not divorced from what I can make out.’

‘Well, Anne, these things do take time, after all.’

‘How would you know?’

There was a small, offended pause.

‘Sorry, Janet. I’m rather at the end of my tether at the moment.’

‘Of course,’ she said, the words sounding strangulated. ‘Well, look after yourself, Anne, and I’ll call tomorrow.’

‘Thank you. Bye.’

‘Bye.’

Janet hung up and Anne sat still for several minutes, hands on the steering wheel in a precise ten to two position, glaring at the traffic jam in front of her. Then, after a few minutes, she turned on the radio and rotated the volume dial until it was almost too loud to bear.

Anne; Charles (#ulink_d4801532-ffa5-5848-84f4-aecda6364425)

So Charles and Anne became an item, inevitably, irreversibly and without much questioning on either side. Anne had never slept with anyone before, had never even had a boyfriend, and was always mildly astonished if a man expressed that sort of sexual interest in her. It hadn’t really crossed her mind that her friendships with boys could be misinterpreted and this made for several uncomfortable exchanges when news of her alliance with Charles trickled down through the college hierarchies.

‘But I thought you liked me,’ said a second-year undergraduate called Fred, with meek desperation. Anne could not conceal her bafflement.

‘Fred, we’re friends,’ she said, shaking her head at the sudden impossibility of it all. ‘Can’t we just be good friends?’

She couldn’t understand why her relations with men were suddenly constrained, punctuated by pockets of conversational difficulty and unease. Charles laughed at her when she told him.

‘Can you really not see the effect you have on men?’

‘But I’ve only ever been nice to them,’ she protested, feebly.

‘That’s the problem,’ he said. ‘You shouldn’t be too nice. It’s easy to misinterpret.’

For the first few weeks, being with Charles had been a glorious bubble of shared experience – of kissing and hand-holding and staring meaningfully at each other across a restaurant table; of buying roses and eating sticky buns for tea-time; of sitting next to each other in lectures and giggling under their breath at some inexplicable mutual joke. The sex, when it came, had been perfectly nice. It had not been the cataclysmic cymbal-clash that Anne had secretly anticipated for years. Nor had it been a painful, brutal semi-disaster of fumbling and not-quite-knowing. It had been a fleshy clasping of two bodies, a swift exchange of fluids, a brief glimpse of half-shut eyes and then, for a few seconds afterwards, a sense of tenderness, of having achieved a closeness that seemed secret from the rest of the world. He enjoyed it more than she did, if enjoy was the word. He seemed to view it as some sort of necessity or duty: a task to be performed to his best ability, without much concern for the pleasure it could bring the other person.

But, at last, Anne felt she had gained access to a tantalising adult existence that had only ever been hinted at. She assumed that other people had sex just like they did, the same physical bargain struck swiftly under the blankets. She never questioned Charles, given that he seemed so much more experienced than her. He knew what to do. She let him get on with it.

As if to compensate for the lack of physical passion, she became gently obsessed instead with the trace and curve of his body: the downy plump cushion of his earlobe, the unexpectedly ticklish patch behind his knee, the twisted purple of veins running down his forearm. She liked to kiss him awake in the mornings, starting at the tip of his forehead and running down past the fragile skein of his eyelids, meeting his lips at the last moment, the exhalation of his breath metallic against her tongue.

‘Morning,’ he would say, blue eyes lazily opening.

Frieda was unconvinced and sulky about the burgeoning relationship. ‘You spend all your time together,’ she said at dinner in hall one evening. ‘I never see you any more.’