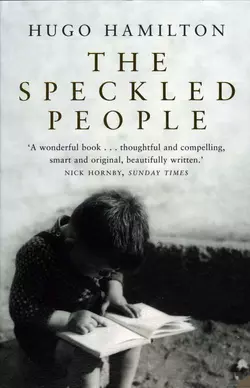

The Speckled People

Hugo Hamilton

‘This is the most gripping book I've read in ages … It is beautifully written, fascinating, disturbing and often very funny.’ Roddy DoyleThe childhood world of Hugo Hamilton, born and brought up in Dublin, is a confused place. His father, a sometimes brutal Irish nationalist, demands his children speak Gaelic, while his mother, a softly spoken German emigrant who has been marked by the Nazi past, speaks to them in German. He himself wants to speak English. English is, after all, what the other children in Dublin speak. English is what they use when they hunt him down in the streets and dub him Eichmann, as they bring him to trial and sentence him to death at a mock seaside court.Out of this fear and guilt and often comical cultural entanglements, he tries to understand the differences between Irish history and German history and turn the twisted logic of what he is told into truth. It is a journey that ends in liberation, but not before he uncovers the long-buried secrets that lie at the bottom of his parents wardrobe.In one of the finest books to have emerged from Ireland in many years, the acclaimed novelist Hugo Hamilton has finally written his own story – a deeply moving memoir about a whole family's homesickness for a country they can call their own.

The Speckled People

Hugo Hamilton

‘I wait for the command to show my tongue. I know he’s going to cut it off, and I get more and more scared each time.’

Elias Canetti

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u853e3e37-ec76-5a12-9831-fd58272153db)

Title Page (#u0e908caa-c6f6-53e5-aba6-0ad3fbe5d084)

Epigraph (#u069d8a17-7183-5bd7-980c-157a76329c89)

One (#ue2a431d6-6442-59ae-9970-6465e505c7a4)

Two (#uab6d4d9d-b40a-578f-a03d-a19934ec3211)

Three (#u22684170-0f82-5dad-b4d7-461557b665ea)

Four (#u133b7ca4-217e-5225-b6fb-d630056e3fa1)

Five (#u85aad810-e87b-508c-a9d6-fbc594872155)

Six (#u473a9ec2-fa9e-574b-adc3-7c9754698384)

Seven (#u3f86e088-b974-5a45-9ddb-ebcff3b4f225)

Eight (#u29df5a71-34c8-514c-8d6b-dd693f42d760)

Nine (#ub93c7a7e-6e8b-58db-9d05-06ff0fecb23e)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Twenty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#ulink_9c7beb47-266a-5206-8988-72337d31fa8e)

When you’re small you know nothing.

When I was small I woke up in Germany. I heard the bells and rubbed my eyes and saw the wind pushing the curtains like a big belly. Then I got up and looked out the window and saw Ireland. And after breakfast we all went out the door to Ireland and walked down to Mass. And after Mass we walked down to the big green park in front of the sea because I wanted to show my mother and father how I could stand on the ball for a count of three, until the ball squirted away from under my feet. I chased after it, but I could see nothing with the sun in my eyes and I fell over a man lying on the grass with his mouth open. He sat up suddenly and said, ‘What the Jayses?’ He told me to look where I was going in future. So I got up quickly and ran back to my mother and father. I told them that the man said ‘Jayses’, but they were both turned away, laughing at the sea. My father was laughing and blinking through his glasses and my mother had her hand over her mouth, laughing and laughing at the sea, until the tears came into her eyes and I thought, maybe she’s not laughing at all but crying.

How do you know what that means when her shoulders are shaking and her eyes are red and she can’t talk? How do you know if she’s happy or sad? And how do you know if your father is happy or whether he’s still angry at all the things that are not finished yet in Ireland. You know the sky is blue and the sea is blue and they meet somewhere, far away at the horizon. You can see the white sailing boats stuck on the water and the people walking along with ice-cream cones. You can hear a dog barking at the waves. You can see him standing in the water, barking and trying to bite the foam. You can see how long it takes for the sound of the barking to come across, as if it’s coming from somewhere else and doesn’t belong to the dog at all any more, as if he’s barking and barking so much that he’s hoarse and lost his voice.

When you’re small you know nothing. You don’t know where you are, or who you are, or what questions to ask.

Then one day my mother and father did a funny thing. First of all, my mother sent a letter home to Germany and asked one of her sisters to send over new trousers for my brother and me. She wanted us to wear something German – lederhosen. When the parcel arrived, we couldn’t wait to put them on and run outside, all the way down the lane at the back of the houses. My mother couldn’t believe her eyes. She stood back and clapped her hands together and said we were real boys now. No matter how much we climbed on walls or trees, she said, these German leather trousers were indestructible, and so they were. Then my father wanted us to wear something Irish too. He went straight out and bought hand-knit Aran sweaters. Big, white, rope patterned, woollen sweaters from the west of Ireland that were also indestructible. So my brother and I ran out wearing lederhosen and Aran sweaters, smelling of rough wool and new leather, Irish on top and German below. We were indestructible. We could slide down granite rocks. We could fall on nails and sit on glass. Nothing could sting us now and we ran down the lane faster than ever before, brushing past nettles as high as our shoulders.

When you’re small you’re like a piece of white paper with nothing written on it. My father writes down his name in Irish and my mother writes down her name in German and there’s a blank space left over for all the people outside who speak English. We’re special because we speak Irish and German and we like the smell of these new clothes. My mother says it’s like being at home again and my father says your language is your home and your country is your language and your language is your flag.

But you don’t want to be special. Out there in Ireland you want to be the same as everyone else, not an Irish speaker, not a German or a Kraut or a Nazi. On the way down to the shops, they call us the Nazi brothers. They say we’re guilty and I go home and tell my mother I did nothing. But she shakes her head and says I can’t say that. I can’t deny anything and I can’t fight back and I can’t say I’m innocent. She says it’s not important to win. Instead, she teaches us to surrender, to walk straight by and ignore them.

We’re lucky to be alive, she says. We’re living in the luckiest place in the world with no war and nothing to be afraid of, with the sea close by and the smell of salt in the air. There are lots of blue benches where you can sit looking out at the waves and lots of places to go swimming. Lots of rocks to climb on and pools to go fishing for crabs. Shops that sell fishing lines and hooks and buckets and plastic sunglasses. When it’s hot you can get an ice pop and you can see newspapers spread out in the windows to stop the chocolate melting in the sun. Sometimes it’s so hot that the sun stings you under your jumper like a needle in the back. It makes tar bubbles on the road that you can burst with the stick from the ice pop. We’re living in a free country, she says, where the wind is always blowing and you can breathe in deeply, right down to the bottom of your lungs. It’s like being on holiday all your life because you hear seagulls in the morning and you see sailing boats outside houses and people even have palm trees growing in their front gardens. Dublin where the palm trees grow, she says, because it looks like a paradise and the sea is never far away, like a glass of blue-green water at the bottom of every street.

But that changes nothing. Sieg Heil, they shout. Achtung. Schnell schnell. Donner und Blitzen. I know they’re going to put us on trial. They have written things on the walls, at the side of the shop and in the laneways. They’re going to get us one of these days and ask questions that we won’t be able to answer. I see them looking at us, waiting for the day when we’re alone and there’s nobody around. I know they’re going to execute me, because they call my older brother Hitler, and I get the name of an SS man who was found in Argentina and brought back to be put on trial for all the people he killed.

‘I am Eichmann,’ I said to my mother one day.

‘But that’s impossible,’ she said. She kneeled down to look into my eyes. She took my hands and weighed them to see how heavy they were. Then she waited for a while, searching for what she wanted to say next.

‘You know the dog that barks at the waves?’ she said. ‘You know the dog that belongs to nobody and barks at the waves all day until he is hoarse and has no voice any more. He doesn’t know any better.’

‘I am Eichmann,’ I said. ‘I am Adolf Eichmann and I’m going to get an ice pop. Then I’m going down to the sea to look at the waves.’

‘Wait,’ she said. ‘Wait for your brother.’

She stands at the door with her hand over her mouth. She thinks we’re going out to Ireland and never coming back home again. She’s afraid we might get lost in a foreign country where they don’t have our language and nobody will understand us. She is crying because I’m Eichmann and there is nothing she can do to stop us going out and being Nazis. She tells us to be careful and watches us going across the street until we go around the corner and she can’t see us any more.

So then we try to be Irish. In the shop we ask for the ice pop in English and let on that we don’t know any German. We’re afraid to be German, so we run down to the seafront as Irish as possible to make sure nobody can see us. We stand at the railings and look at the waves crashing against the rocks and the white spray going up into the air. We can taste the salt on our lips and see the foam running through the cracks like milk. We’re Irish and we say ‘Jaysus’ every time the wave curls in and hits the rocks with a big thump.

‘Jaysus, what the Jaysus,’ I said.

‘Jaysus, what the Jaysus of a big huge belly,’ Franz said, and then we laughed and ran along the shore waving our fists.

‘Big bully waves,’ I shouted, because they could never catch us and they knew it. I picked up a stone and hit one of the waves right in the under-belly, right there as he stood up and rushed in towards us with his big, green saucer belly and his fringe of white hair falling down over his eyes.

‘Get down, you big bully belly,’ we laughed, as the stone caught the wave with a clunk and there was nothing he could do but surrender and lie down across the sand with his arms out. Some of them tried to escape, but we were too fast for them. We picked up more and more stones and hit them one by one, because we were Irish and nobody could see us. The dog was there barking and barking, and we were there holding back the waves, because we didn’t know any better.

Two (#ulink_49c8dee3-cf8b-5bc7-b081-abf162490766)

I know they don’t want us here. From the window of my mother and father’s bedroom I can see them walking by, going from the football field around by our street and down to the shops again. They carry sticks and smoke cigarette butts and spit on the ground. I hear them laughing and it’s only a matter of time before we have to go out there and they’ll be waiting. They’ll find out who we are. They’ll tell us to go back to where we come from.

My father says we have nothing to worry about because we are the new Irish. Partly from Ireland and partly from somewhere else, half-Irish and half-German. We’re the speckled people, he says, the ‘brack’ people, which is a word that comes from the Irish language, from the Gaelic as they sometimes call it. My father was a schoolteacher once before he became an engineer and breac is a word, he explains, that the Irish people brought with them when they were crossing over into the English language. It means speckled, dappled, flecked, spotted, coloured. A trout is brack and so is a speckled horse. A barm brack is a loaf of bread with raisins in it and was borrowed from the Irish words bairín breac. So we are the speckled-Irish, the brack-Irish. Brack home-made Irish bread with German raisins.

But I know it also means we’re marked. It means we’re aliens and we’ll never be Irish enough, even though we speak the Irish language and my father says we’re more Irish than the Irish themselves. We have speckled faces, so it’s best to stay inside where they can’t get us. Inside we can be ourselves.

I look out the window and see the light changing on the red-bricked terrace across the street. I see the railings and the striped canvas sun-curtains hanging out over the front doors. There’s a gardener clipping a hedge and I hear the sound of his shears in English, because everything out there is spoken in English. Out there is a different country, far away. There’s a cloud moving over the street and I can see the gardener looking up. I hear my mother behind me saying that there’s something strange about the light this afternoon. She says the sun is eclipsed by the cloud and throws a kind of low, lantern light across the red-bricked walls and it feels like the end of the day.

‘Falsches Licht,’ she calls it, because everything inside our house is spoken in German, or in Irish. Never in English. She comes to the window to look for herself and says it again, false light. She takes in a deep breath through her teeth and that means it’s going to rain. It means the seagulls will soon come in from the sea and start screeching and settling on the chimneys. It’s a sign for people to run out and bring in their washing. A sign for the gardener to go inside, because large drops are already appearing on the pavement. And when all the drops are joined together and the pavement is fully wet, then my mother goes downstairs to the kitchen.

She lets us play with some of her things. My older brother Franz, my younger sister Maria and me examine everything on her dressing table – lipstick, scissors, nail clippers, rosary beads. There’s a brush lying on its back with a white comb stuck into it like a saw. A bowl of hair clips and a box of powder and a gold and blue bottle with the big number 4711 written on it. We empty out a box of jewellery and find the emerald snake which my mother calls the Smaragd. Maria keeps calling out the big number 4711 as she blesses herself around the ears and on the wrists and behind the knees, again and again, just like my mother does, and the whole room fills up with scent of cologne. I look at the print that the hairbrush makes on my arm. Franz finds the crocodile-skin purse with lots of heavy silver coins inside and we’re rich. The smell of rain and leather are mixed together all in one with the smell of cologne. In the drawers on each side of the dressing table we find letters, scarves and stockings. Passports and photographs, rail tickets, sleeper accommodation on night trains.

And then we came across the medals. I knew immediately that they were German medals because everything that belongs to my mother is German. She tells us lots of stories about Kempen where she grew up, so I knew that my grandfather Franz Kaiser was in the First World War and that my mother was in the Second World War. I knew that my grandmother Berta was an opera singer and that my grandfather Franz once went to listen to her sing at the state opera house in Krefeld, and because everyone else was sending her flowers, he decided to send her a bouquet of bananas instead, and that’s how they fell in love and got married. Sometimes my mother puts on the radio to see if she can hear some of the songs that her own mother sang. I know how far away Germany is by the way my mother sometimes has shadows around her eyes. By the way she stays silent. Or by the way she sometimes throws her head back and laughs out loud at some of the things that her father used to do. Like the time he once asked to borrow the postman’s cap and said thank you very politely and then climbed up the monument in the middle of the square to put it on top of St George’s head.

We didn’t have to be told that these were military medals which belonged to Franz Kaiser. When he was on duty during the First World War, his wife Berta brought him his dinner once a day by train in a straw basket. Sometimes she just put the straw basket on the train by itself and it came back empty in the evening. Then he had to go to the front one day and came back with a disease in his lungs that killed him. He was not well even before the war started and my mother says he should never have been taken into the army because he died when she was only nine years old. She says she still remembers the smell of flowers in the room around his coffin and the shadows around her mother’s eyes. So I put on Franz Kaiser’s medal with the cross and march up and down the bare floorboards of my mother and father’s bedroom, looking at myself in the mirror of the dressing table and saluting, while my brother salutes behind me with his own medal and my sister behind him with the emerald snake.

Then the sun lit up the street outside and I thought somebody had switched on a light in the room. The cloud had already passed over and gone somewhere else and there was steam rising from the pavement. The gardener was back out, clipping the hedge, and there was no other sound anywhere except my sister Maria breathing through her mouth and sometimes the sound of a train in the station. The smell of baking was coming all the way up the stairs from the kitchen and we should have rushed down to get the leftovers in the bowl. We should have been running up to collect my father from the train. But we were too busy looking for all these old things.

At first there was nothing much in my father’s wardrobe, only cufflinks, ties and socks. But then we found a big black and white picture of a sailor. He was dressed in a sailor’s uniform with square, white lapels over his tunic and a rope lanyard hanging down over his chest. He had soft eyes and I liked the look of him. I wanted to be a sailor, even though I had no idea what this sailor was doing in my father’s wardrobe.

I know that my father comes from Cork and works as an engineer in Dublin and writes his name in Irish. When he was small, Ireland was still under the British. His father’s family were all fishermen. His father fell on deck one day and lost his memory and died not long after that in a hospital in Cork city. But we never talk about that. I knew there would be trouble when my father came home, but I didn’t think about it, not even when I saw the shape of his good Sunday suit swinging on the hanger in front of me. Not even when I heard the trains coming into the station, one by one. We continued to inspect everything quickly, pulling out drawers full of handkerchiefs and gloves and mothballs and socks rolled up.

There were boxes at the bottom of the wardrobe, full of letters and postcards, certificates and holy pictures. And at last we came across more medals. Heavy bronze medals this time, one for each of us. The medal I put on hung from a striped ribbon that was just like the faded sun-curtains across the street. We didn’t know where these new bronze medals came from, except that they must have belonged to the sailor hiding at the back of the wardrobe. Whoever he was, he must have owned the waterproof identity papers, too, and the photographs of HMS Nemesis with sailors lined up in a human chain along the deck. And he must have got all the postcards from King George wishing him a happy and victorious Christmas.

Some things are not good to know in Ireland. I had no idea that I had an Irish grandfather who couldn’t even speak Irish. His name was John Hamilton and he belonged to the navy, the British navy, the Royal Navy. He joined up as a boy of fifteen and served on all kinds of ships – Defiance, Magnificent, Katoomba, Repulse. He fell on a British naval vessel called HMS Vivid when he was only 28 years of age. He died because he was homesick and lost his memory. But I didn’t know any of that. There’s a picture in the front room of Franz Kaiser and Berta Kaiser with her head leaning on his shoulder, both of them laughing with a big glass of wine on the table in front of them. There’s no picture of John Hamilton or his wife Mary Frances, alone or together, hanging anywhere in our house. Our German grandparents are dead, but our Irish grandparents are dead and forgotten. I didn’t know that the bronze medal I was wearing beside the Iron Cross belonging to my German grandfather came from the British navy and was given to my Irish grandmother, Mary Frances, along with a small British war widow’s pension which she had to fight for. I didn’t know that my Irish grandfather, John Hamilton, and my German grandfather, Franz Kaiser, must have stood facing each other in the Great War. Or that my mother and father were both orphaned by that same war. Or that I was wearing the medals of two different empires side by side.

I didn’t know what questions to ask. I heard the trains coming home one by one and I knew that we were not allowed to speak the language of the sailor. It’s forbidden to speak in English in our house. My father wants all the Irish people to cross back over into the Irish language so he made a rule that we can’t speak English, because your home is your language and he wants us to be Irish and not British. My mother doesn’t know how to make rules like that, because she’s German and has nothing against the British. She has her own language and came to Ireland to learn English in the first place. So we’re allowed to speak the language of Franz Kaiser, but not the language of John Hamilton. We can speak Irish or German, but English is like a foreign country outside the door. The sailor in the wardrobe, with his short haircut and his soft eyes looking away, was not able to talk to us. Even if he was still alive and came to visit us and was ready to tell us all about his travels around the world on those ships, about all the cities and ports he had been to, I could not have asked him any questions.

There were so many boxes at the bottom of the wardrobe that we could sit on them and pretend we were on a bus. We called it the number eight bus, and Franz was the driver holding a hat for a steering wheel. I was the conductor bedecked in medals, and Maria was the only passenger apart from my father’s Sunday suit hanging on the rail and the quiet sailor in the back seat looking away out the window.

‘Hold the bar please,’ I called and Maria got on. She was carrying her crocodile-skin purse and paid the fare with the precious coins.

‘Fares please,’ I kept demanding, until she had no money left and I had to let her on without paying. I rang the bell with my fist against the handle of the drawer. Then I closed the door and the wardrobe drove off in the complete darkness. Maria cried and said she wanted to get off, but it was already too late for that, because the bus was going so fast that it started leaning over. Before we knew it, the whole wardrobe was lying on its side. The only thing stopping it from crashing all the way down to the floor was my mother and father’s bed. We didn’t even know what happened. All we knew was that we were now trapped inside and unable to open the door. We knew there would be trouble. We were silent for a while, waiting to see what would happen next. Maria kept crying and then Franz started calling for help.

‘Mutti, Ma Ma …’ he said.

I started calling as well. My mother was far away downstairs in the kitchen baking the cake. We called and called and waited for a long time. But nobody could hear us, not even the gardener or the neighbours or anyone out on the street, because they could only hear things that were said in English. Nobody even knew that we were calling for help, because we had the wrong words. We were the children in the wardrobe and no matter how loud we shouted and knocked, they could hear nothing.

Some time later I heard my mother’s voice outside saying that she could not believe her eyes. She said she had seen a lot of strange things in Germany during the war, and in Ireland, too, after she came over, but never before had she seen a wardrobe on its side, crying. She was not able to lift the wardrobe by herself, or to open the door because it was jammed shut against the bed. But everything was going to be all right in the end, she said, because even if we had to stay in the dark for a while longer, she would tell us a story until help came. We listened to her and almost fell asleep with the fog of 4711 and mothballs and the cake downstairs, until my father came home and the wardrobe suddenly stood up and the door opened. It was daytime again. I rubbed my eyes and saw my father blinking through his glasses and saying everything with a frown on his forehead.

‘Who gave you the right to look at my things?’ he said, because he didn’t want any of us to know that he had a father in the navy who could not speak Irish and once stood with the British in a war against the Germans, when his own country was still not free.

Maria was huddled in my mother’s arms, crying even more after she was rescued than before when she was trapped. She said Franz was the driver and I was the conductor and she was only a passenger, like the sailor in the back seat. My father’s voice filled the room and I felt the sting of his hand, but it was nothing because soon we were all safe again and my mother was talking about the cake for after dinner. The medals were taken off and put away. The picture of the sailor with the soft eyes disappeared and we never saw him again after that. Nobody mentioned him. I had no way of keeping him in my head because he was gone, back into the wardrobe where nobody could rescue him. We didn’t know how to remember him, and like him, we lost our memory.

Three (#ulink_ad8806d1-1a97-5cfc-b885-3605a498e9d5)

My mother’s name is Irmgard and she was in a big film once with lots of war and killing and trains on fire. It’s a black and white picture that happened long ago in Germany. A man trapped her in a place called Venlo where she was working and she couldn’t escape. She says it was just like us being in the wardrobe because she was far away from home and couldn’t call for help. She couldn’t write home or tell any of her sisters what was happening. She didn’t know who to talk to. The man’s name was Stiegler and he would not listen to her when she spoke to him and would not let her go. Instead he told her to smile. And even though she was too afraid to smile, he just put his hand up to her lips and made her show her teeth like a big unhappy grin. She can’t talk about it any more than that. She has told nobody else, not even her sisters, not even my father. One day, when we get older we’ll hear the whole story. But now we’re too small, and some things about Germany are not good to think about. ‘That’s a film you can see when you grow up,’ she says.

All we need to know is that at the end of the film, when the war is over, my mother runs away to Ireland to go on a pilgrimage. She meets my father in Dublin and they talk about everything except the time she was trapped once by the man in Venlo. They go back to Germany to get married with the snow all around. They travel through the white landscape and go to a mountain along the River Rhine called the Drachenfelz, and after that my father brings her back to Ireland to another mountain close to the Atlantic called Croagh Patrick.

‘And that’s how the film ends,’ she says, because it’s time to sleep and she doesn’t want us to keep calling her and asking more questions about Germany that she can’t answer. ‘The End. Film over.’ She says the same thing sometimes when we start fighting over the leftovers of the cake bowl. Or the time we went to the strand and stayed there all day until it started raining and she said it was a pity it had to end like that. Or when something breaks, like the time the blue vase that came from her father and mother’s house in Kempen smashed in the hallway and she said it was a very nice film but now it was over.

In my mother’s film, she was in a building where there was nobody else living. At night when everybody was gone, she was afraid and locked the door of her room. She knew that there was no point in shouting for help, because nobody would hear her. Then she heard the man coming in and there was nothing she could do except pray and hope that it would be all over some day. She could hear him coming up the stairs as if he was counting them on the way up. She could hear him breathing outside the door. She could see the doorknob turning and she could smell cognac.

During the day, the man was always very nice to everybody. He looked very well, dressed in a suit and a clean shirt every morning, and he wore good shoes. He spoke kindly and shook hands with everyone when they arrived to work. He smiled and even remembered everybody’s birthday. He brought flowers to work when somebody had bad news. Everybody said he was a good man during the day and full of compliments. He had read a lot of books and he was very generous, giving presents of theatre tickets and opera tickets.

But you can’t always trust nice people. My mother says that sometimes there is no defence against kindness. It’s easy to be taken in by compliments, by smiles, by nice words. But you can’t let yourself be stung by things like flowers and theatre tickets and invitations to the opera. Everybody can make mistakes but there are some mistakes you can’t even talk about, because you feel so stupid that you can only blame yourself. My mother wants us never to be fooled by nice words. She wants us never to have things that we regret, because everybody in Germany has things in their heads that they keep to themselves. Everybody has things they wish had never happened.

When you’re small you can inherit a secret without even knowing what it is. You can be trapped in the same film as your mother, because certain things are passed on to you that you’re not even aware of, not just a smile or a voice, but unspoken things, too, that you can’t understand until later when you grow up. Maybe it’s there in my eyes for all to see, the same as it is in my mother’s eyes. Maybe it’s hidden in my voice, or in the shape of my hands. Maybe it’s something you carry with you like a precious object you’re told not to lose.

‘That film will still be running when we grow up,’ she says.

All we need to know for now is that she ran away to Ireland to become a pilgrim in a holy country with priests and donkeys that had crosses on their backs. She picked Ireland because she heard there were lots of monastic ruins. She didn’t expect so much poverty. But the Irish people knew how to deal with poverty, through celebration, with smoke and stories and singing. A man with a packet of cigarettes was a millionaire in Ireland. And the Irish people had never tried to hurt anyone. So maybe they would not pass judgement on a German woman. In the days before she left Germany, it was so exciting, she says, because nobody in her family had ever been that far away before. Everybody was talking about Ireland, even the neighbours, asking what the weather was like and what the houses were like inside. What she should bring and what she didn’t need. She said she packed and unpacked all over again so often that it was hard to believe she was going away at all in the end.

At the station, she embraced her aunt Ta Maria and her Onkel Gerd and her youngest sister Minne, but it was hard to feel she was leaving. They all had tears in their eyes and would not let her get on the train because they thought she would never come back. They made her promise to write home every week. Even when she was sitting down in her seat, even when the train carriages jerked and the train moved out of the station, it was still hard to feel anything except fear. Everybody in Germany was used to being afraid. She waved her hand slowly. She saw the houses and the fences and the fields passing by, but she still had the feeling that she was trapped. But then, my mother says, there comes a moment when you don’t care about anything, when all fear and doubt disappear. It’s a moment of weakness and strength at the same time, when nothing matters and you’re not afraid any more.

Sometimes she still thinks about it as though it just happened yesterday, as though the film is never over and she’ll never escape. Maybe the reason why people are good at stories is that they sometimes have things they can’t tell, things they must keep secret at all costs and make up for in other ways. So she tells us the story of the pilgrimage instead. She tells us how Ireland was a place where you could trust everyone, where people prayed every day, where you could go and say the rosary and make up for all the things that happened in the war.

It was a great way for a film to come to an end, cycling along the small roads with the sun slanting through the clouds like in holy pictures, lighting up the mountains like a stage in the opera house. It was flickering through the stone walls. Everywhere these stone walls and everywhere the grass combed in one direction by the wind. Trees bent like old men and everywhere so empty except for the haystacks in the fields and the monastic ruins. Once or twice along the way there were cows on the road that made her stop completely. Big cow faces looking at her, as if they were amazed to see a German woman in Ireland after the war.

Then it started raining and getting dark and she had to find a place to stay quickly. It was raining so much that the water was jumping away from her eyes when she blinked and her shoulders were shivering. She got off the bicycle because it was impossible to go any further. A man pointed to a house that didn’t even look like a guest house, but it was better to stay there because you couldn’t see a thing any more. There was a light on inside and the woman of the house came to the door with lots of children behind her. One girl had her dress in her mouth, all of them staring as if my mother had come in with the rain.

‘It’s not often we see a German woman cycling around these parts on her own,’ the woman said.

My mother says you can’t be sure in Ireland if people say things with admiration or not. Irish people are good at saying things in between admiration and accusation, between envy and disdain. She says the woman looked her up and down as if she liked German clothes but didn’t completely trust her.

‘I have come from Lough Derg,’ my mother explained.

That made everything right. She was a pilgrim. A pilgrim coming to Ireland to pray for all the bad things that happened in Europe.

In the kitchen, they made her sit and eat a meal while they all watched and the man of the house kept asking questions about Germany. Was it in ruins like they said in the papers? She had to describe the cities after the war – Nuremberg, Hamburg, Dresden. The woman of the house kept saying ‘You’re not serious’, but people in Germany wouldn’t make up something like that. The children kept staring. They were so shy that they were afraid to move closer to her. It was like being a film actress. They spoke about her as if she was still in a film. She’ll have some more bread, the man of the house said. She’ll be needing a glass of whiskey, he said after she was finished eating, as if they had to celebrate the guest who came in with the rain.

The man of the house raised his glass with all the children looking up.

‘Heil Hitler,’ he said.

There was a big smile on his face, my mother says, and she didn’t know what to say. Of course, he was only being friendly. It was part of the Irish welcome.

‘Fair play to the Germans,’ he said.

He said the Germans were great people altogether. He kept saying it was a pity they lost because they were a mighty nation. He winked at her with admiration, then left a long silence, waiting to see how she would respond.

‘Fair play to the Germans, for the almighty thrashing you gave the British. Fair play to Hitler for that, at least.’

He was only being hospitable, my mother says, to make her feel at home. She could not argue with him. She was trapped inside German history and couldn’t get out of it. Instead she smiled and said it had been a long journey back from Lough Derg. She thanked them for such a lovely welcome, but said she could no longer keep her eyes open.

She was given a room with a small fire going. Her clothes were still steaming. There was a smell of cabbage and damp walls. The bed sank down in the middle, but she was so tired that nothing mattered any more and it didn’t take long to fall asleep to the sound of the rain. She heard the voices of children on the far side of the wall and sometimes the man of the house, too, speaking in a deep voice. But the rain was whispering and bouncing into an enamel basin outside and rushing away into a drain like the sound of the rosary being said all night.

Sometime later she woke up and saw the woman of the house standing beside the bed, holding a lamp, gently shaking her arm. The woman explained that there was an emergency. Would she mind giving up the bed and spending the night in another room? There were three men soaked to the skin outside on the doorstep needing accommodation for the night.

‘I can’t turn them away,’ the woman said. ‘Poor creatures.’

My mother says she had to get up and take her things to the family room where the woman pointed to the marriage bed. The children were all fast asleep in another bed. And the room was in such a mess, with clothes and newspapers on the floor, bits of food, too, even a harness for a horse and a hay-fork and wellington boots. She stood there looking around as if she couldn’t believe her eyes.

‘It’s only topsy dirty,’ the woman said.

‘But where is your husband?’

‘You have nothing to be afraid of, love. He’ll stay by the fire.’

My mother says you can’t complain if you’re a pilgrim escaping from Germany. She says you have to offer things up. For people who are less fortunate and for all the awful things that happened. So she just got into bed with the woman of the house. She felt the warmth left behind by the man of the house. She could hear the whole room breathing, until the woman started speaking in the dark. She listened to the woman talking for a while, and then she began to talk as well, as if there were things that could only be said in the dark.

She says she never saw the men. She heard them coming in and muttering for a while to each other in the room. She never saw the man of the house again either, but she heard him in the kitchen, tapping his pipe against the fireplace. She heard the children dreaming sometimes and the cows elbowing each other in the barn outside. She smelled the rain and heard it drumming on the roof, like somebody still saying the rosary. They whispered so as not to wake up the children. They talked for a long time as if they were sisters.

Four (#ulink_71e2e929-72c8-50de-927e-596a0fbca0bd)

On the front door of our house there is the number two. I know how to say this number in German: Zwei. My mother teaches us how to count up the stairs: Eins, Zwei, Drei … And when you get to ten you can start again, so many steps all the way up that you can call them any number you like. And when we’re in our pyjamas, we say goodnight birds and goodnight trees, until my mother counts again very quickly and we jump into bed as fast as possible: Eins, Zwei, Drei.

There are workers in the house and they know how to smoke. They made a mountain in the back garden and sit on it, drinking tea and eating sandwiches. They smoke cigarettes and mix sand and cement with a shovel. They whistle and make a hole in the middle where they pour in the water to make a lake, and sometimes the water from the lake spills over the side before the shovel can catch it. We do the same with spoons. The workers have different words, not the same as my mother, and they teach us how to count in English: one, two, three … But my father says that’s not allowed. He says he’ll speak to them later.

One day there was a fox in the kitchen, just like the fox in the story book. The workers were gone, so my mother closed the door and called the police. Then a Garda came to our house and went into the kitchen on his own and started banging. There was a smell of smoke and we waited on the stairs for a long time, until the Garda came out again with the fox lying dead on a shovel with his tail hanging down and blood around his mouth and nose.

‘You’ll have no more strangers in your house, please God,’ he said.

The Garda showed his teeth to my mother and called her ‘Madam’. The workers called her ‘Maam’. We called her ‘Mutti’ or ‘Ma Ma’ and my father is called ‘Vati’ even though he’s from Cork. The Garda had a moustache and said it was no fox we had in the kitchen but a rat the size of a fox. And the rat was very glic, he said, because he hid behind the boiler and would not come out until he was chased out with fire and smoke.

There are other people living at the top of our house, all the way up the stairs, further than you can count. They’re called the O’Neills and they never take their hats off, because they think the hallway is like the street, my mother says. They are very noisy and my father makes a face. He goes up to speak to them and when he comes down again he says he wants the O’Neills out of the house. There will be no more chopping wood under this roof.

Áine came to look after us when my mother had to go away to the hospital. She’s from Connemara and has different words, not the same as the workers, or the O’Neills, or the Garda, or my mother. She teaches us to count the stairs again in Irish: a haon, a dó, a trí … She doesn’t lay out the clothes at night or tell stories. She doesn’t call me Hanni or Johannes, she calls me Seán instead, or sometimes Jack, but my father says that’s wrong. I should never let anyone call me Jack or John, because that’s not who I am. My father changed his name to Irish. So when I grow up I’ll change my name, too.

Áine can’t speak my mother’s words, but she can speak the words of the Garda. She brings us for a walk along the seafront and shows us the crabs running sideways and the dog barking for nothing all day. She says she wants to go to London, but it’s very far away. And Connemara is far away, too. I said London was far away one, and Connemara was far away two, and she said: ‘Yes.’ She sits for a long time looking out across the sea to London. Then she takes us up to the shops to buy sweets and I get more than Franz because I’m very glic. She teaches us how to walk on the wall, all the way back along the seafront, and Franz makes up a song about it: ‘Walk on the wall, walk on the wall …’

My mother came back with a baby called Maria, so that’s Franz, Johannes and Maria: Eins, Zwei, Drei. We speak German again and my mother shows us how to feed the baby with her breast. Maria opens her mouth and shakes her head and then my mother has to change her nappy because the baby did ‘A A’. After that, my mother puts Maria out in the garden with a net across the pram to stop the birds from stealing her dreams.

Áine took us down to the sea again because Franz had a fishing net and he was going to catch one of the crabs, but they were too fast. I said they were all ‘two fast and three fast’, and Áine said: ‘Yes.’ She took out a box with a small mirror and put lipstick on her lips. She took off her shoes to put her feet into one of the pools with the crabs. I started throwing stones into the pools. Franz got all wet and Áine said ‘A A’ in Irish. Then I threw a stone in Áine’s pool. She chased after me and on the way home she would not let me walk on the wall, so I tried to walk sideways, like the crabs.

My mother knows everything. She knows that I was throwing stones, but Áine said it wasn’t ‘half as bad as that’, which is the same as what my mother says only in different words: Halb so schlimm. My mother wagged her finger and said: Junge, Junge, which is the same as what Áine says in English: ‘Boy, oh boy’, and in Irish ‘a mhac ó’.

That evening, my mother brought us up to the station to collect my father from the train. She picked us up to look over the wall at the tracks. We waved and shouted at the train rushing through under the bridge and then we started running towards my father coming out of the station. My father is different to other men. He has no moustache, but he has glasses and he has a limp, too. He swings his briefcase and his leg goes down on one side as if the ground is soft under one foot. It’s the same as when you walk with one foot on and one foot off the pavement. My mother kisses him and puts her arm around him. He looks into the pram at Maria to see if she has her eyes open. Franz tries to carry the briefcase and I try to walk like my father, but that’s not allowed. He hits me on the back of my head and my mother kneels down to say it’s not right to imitate people. You always have to walk like yourself, not like your father or the crabs, just like yourself. At home, my father was still angry. He wanted to know why I was throwing stones at the pools so I told him that Áine said ‘A A’ in Irish. I mixed up the words like sand and cement and water. I used Áine’s words and told my father that she said ‘A A’, what the baby did, in my mother’s words.

‘What did you throw?’ my father asked.

‘Stones.’

I saw myself twice in his glasses and he made a face, just like when the O’Neills were chopping wood upstairs.

‘Stones,’ he said again, very loud. Then he stood up.

My mother was laughing and laughing until the tears came into her eyes. She said it was so funny to hear so many words and so many countries being mixed up.

‘Stones,’ my father said again. ’I won’t have this.’

‘It’s not half as bad as that,’ my mother said, still wiping her eyes.

‘She’s here to speak Irish to them,’ my father shouted, and then my mother tried to stop him going up to speak to Áine. She was holding on to his arm and saying: ’Leave it till the morning. Let me talk to her.’

My father says there will be no more chopping wood and no more speaking English under his roof. I stay awake and look at the light under the door. At night, I hear my mother and father talking for a long time. I hear the O’Neills coming up the stairs and I hear my father coming out on the landing to see if they will start chopping wood. Then the light goes out. I hear water whispering. I hear a fox laughing. I hear stones dropping into the pools and I hear sand and cement being mixed with a shovel. Then it’s silent and nobody is listening, only me.

My mother spoke to Áine the next day. She’s not able to speak Áine’s words. So in the words of the Garda and the workers, my mother tells her never to speak the words of the Garda and the workers to us again.

‘You must try to speak to them in Irish,’ my mother said.

‘What good is that to them?’ Áine said.

‘Please. It’s my husband’s wish.’

So we have to be careful in our house and think before we speak. We can’t speak the words of the Garda or the workers, that’s English. We speak Áine’s words from Connemara, that’s Irish, or my mother’s words, that’s German. I can’t talk to Áine in German and I can’t talk to my mother in Irish, because she’ll only laugh and tickle me. I can talk to my father in German or Irish and he can speak to the Garda and the workers for us. Outside, you have to be careful, too, because you can’t buy an ice pop in German or in Irish, and lots of people only know the words of the Garda and the workers. My father says they better hurry up and learn Irish fast because we won’t buy anything more in English.

Sometimes Áine speaks to herself in the mirror. Sometimes when the O’Neills go through the hall on their way out the front door, my mother says good morning to them, but they say nothing at all and just walk out as if they don’t understand their own language. Sometimes the man in the fish shop says guten Morgen as if he’s forgotten his own language. Sometimes people whisper. Sometimes they spell out the letters of a word. And sometimes people try to forget their own language altogether and Áine continues to say ‘stones’ as if there’s no word in her own language for it.

‘Stone mór’ and ‘stone beag,’ she says. Big stone and little stone.

On Saturday, Áine goes into the city on the bus to speak English. The O’Neills were gone away, too, and my father was in the garden digging. He said he was going to get rid of the mountain the workers left behind and grow flowers and radishes, so I watched him as he jabbed the spade into the soil and then pushed it down with his foot. The worms living in the mountain had to go away in the wheelbarrow. My father emptied it and spread out the soil in another part of the garden. Then he let me hold the wheelbarrow while it was filling up again.

Franz made a wall with a line of bricks and he was walking on it singing: ‘Walk on the wall, walk on the wall …’ My father stopped digging and told him to stop. He made the O’Neill face again. But Franz kept on saying ‘walk on the wall’ because that was his song and he couldn’t forget it. Then my father jabbed the spade into the mountain and it stayed there, standing up on its own while he went over to Franz and hit him. He hit him on the back of the head so that Franz fell off the wall and his face went down on the bricks. When he got up, there was blood all around his nose and mouth, like the fox. He opened his mouth and said nothing for a long time, as if he had forgotten how to use his voice and I thought he was going to be dead. Then he started crying at last and my father took him by the hand very quickly and brought him inside.

‘Mein armer Schatz,’ my mother kept saying as she sat him up beside the sink and started cleaning the blood away from his face. Franz kept crying and trying to say something but he didn’t know what words to use. Then my mother turned around to my father and looked at him as if she could not believe her eyes.

‘His nose is broken,’ she said.

There were drops of blood on the kitchen floor. They made a trail all the way out into the garden. My father said he was very sorry, but the rules had to be obeyed. He said Franz was speaking English again and that had to stop. Then my mother and father had no language at all. My father went outside again and my mother brought Franz upstairs. Even when the blood stopped, he was still crying for a long time and my mother was afraid that he would never start talking again. She sat down on the bed and put her arm around the two of us and told us what happened when she was in Germany in a very bad film. She held us both very hard and I thought my bones would crack. She was crying and her shoulders were shaking. She said she was going to go back to Germany. She would take us with her. She started packing her suitcase, wondering what she should bring and what she should leave behind in Ireland.

I looked out the window and watched my father fill the wheelbarrow and bring it to another part of the garden, empty it and bring it back to start again. I watched him digging and digging, until the mountain was gone. I wanted to go down and tell him that my mother fixed Franz’s nose with a story. I wanted to tell him that I would never say ‘walk on the wall’ as long as I lived. I wanted to tell him that my mother was going home and she was going to take us with her. But he never looked up and he didn’t see me waving. Instead, he made a big fire in the garden and the smoke went across the walls, away over the other gardens, all around the houses and out on to the street. He kept stacking on more and more weeds and leaves with a big fork, as if he wanted to send a message around the whole world with smoke. The fire crackled and whistled, and it smelled like cigarettes. My father was standing with the fork in his hand and sometimes he disappeared. Sometimes the whole house disappeared and people must have thought we were never coming back.

My mother carried Maria in one arm and the suitcase in the other. In the hallway, she put the suitcase down so that she could open the front door and escape on to the street. I knew that my father would be searching for us all over the place in the smoke. But my mother said we were not going to be trapped again. She picked up the suitcase and told us to follow her, but then I heard my father coming in from the garden. His footsteps came all the way as if he was counting the drops of blood on the ground. We tried to run away fast, but it was too late because he was already standing right behind us. I could smell the smoke on his clothes. He asked my mother where she was thinking of going to without any money. He said there was nothing left in Germany and she had nowhere to go home to with three children. He closed the front door and said she was married now, so she sat down on the suitcase and cried.

‘She’s just a bit homesick, that’s all,’ my father said. He smiled and said he would put on some German music. He kissed my mother’s hand and carried the suitcase back up the stairs.

Then the big music filled the whole house. It went into every room and all the way up the stairs. Outside, the fire kept going until it got dark and I stood at the window of the bedroom again with my mother, saying goodbye smoke, goodbye birds, goodbye trees. But we didn’t go anywhere. We stayed in Ireland and my mother told us to get into bed: Eins, Zwei, Drei.

Five (#ulink_e46df1ad-be69-59e2-905a-1bb01ad27e9d)

My father’s name is Jack and he’s in a song, a long ballad with lots of verses about leaving Ireland and emigrating. The song is so long that you couldn’t even sing it all in one day. It has more than a thousand verses, all about freedom and dying of hunger and going away to some other land at the end of it all. My father is not much good at singing, but he keeps repeating the chorus about how we should live in Ireland and be Irish.

‘No more shall we roam from our own native home,’ is what he says when we’re standing at the seafront, holding on to the blue railings, looking out at the white sailing boats. He doesn’t want us to live in England or America where they speak only English and keep dreaming about going back home. So we stay in Ireland where we were born, with the sea between us and all the other countries, with the church bell ringing and the mailboat going out across the water. Instead of always going away, my father had a new idea. Why not bring people from somewhere else over to Ireland? So that’s why he married my mother and now she’s the one who does all the dreaming and singing about being far away from home. It’s my mother who left her own native shores, and that means we still end up living in a foreign country because we’re the children from somewhere else.

My father comes from a small town in west Cork called Leap and he had lots of uncles and cousins who had to emigrate. One of his uncles only sent his first letter back from America after twenty years, just to tell everybody that the rumours still going around in Ireland about a girl he left behind with a baby were not true. It was easy to say what you liked about people who went away. And it was easy for those who left to deny Ireland, to look back and say it was full of poverty and failure. Maybe they made a lot of money abroad, my father says, but they were lonely and they wanted everybody who was left in Ireland to come and join them over there. My father and his younger brother Ted were going to emigrate, too. They lived in a house at the end of the town with their mother and a picture of a sailor over the mantelpiece. They had plans to go to America to work with their uncle, but then they got a scholarship and went to school instead.

The town is called Leap after a famous Irishman by the name of O’Donovan who once got away from the British by leaping across a nearby gorge. Léim Uí Dhonabháin: O’Donovan’s Leap, they call it. The peelers chased him all over the countryside, but he escaped over the impossible gorge and they were afraid to follow him. ‘Beyond the Leap, beyond the law’ is what the people of the town said. There was no freedom at that time. The whole town could hardly jump across the gorge after him, so they stayed behind where they were, under the British. They talked about it and went up there for a walk on summer days to look across to the far side. But nobody could do it. So the town was called after something that might as well not have happened at all. It was called Leap because that’s what the people in the town wished they had done, what they dreamed about and sang songs about.

Lots of them emigrated after that, my father says. The people who stayed told their children that unless they wanted to jump after the famous O’Donovan and spend the rest of their lives running away, they might as well speak English, because that’s all they spoke in places like America and Canada and Australia and South Africa. It was English they spoke on ships and English they spoke in films. The Irish language was bad for business, they said, so why should anyone have to risk his life across a deadly gorge for being Irish? It was madness even to think of it. Everybody in Cork started speaking English and calling each other ‘boy’ at the end of every sentence whether you were young or old. You’d only kill yourself, boy, they said. They started saying they could make the leap across the gorge any time they liked, no problem at all, boy. They said everything twice to make sure you believed them. They claimed they were living beyond the law and there was no need to prove it, boy.

There was lots of killing and dying and big houses on fire in my father’s song, too. He tells us bits of the song, like the time the fighting started around west Cork when they tried to take down the British flag. About children hiding sweets in bullet holes along the wall of the creamery, and about a man named Terence MacSwiney, the Cork lord mayor who died on hunger strike in a London jail. He puts on the record with the song about another man named Kevin Barry who was hanged one Monday morning in Dublin. He tells us about the time when the British soldiers came to their house in Leap, threatening to burn it down because they thought the rebels were shooting from the upstairs window. They had to run away in the middle of the night to Skibbereen and on the way down the hill the cart overturned with their belongings, so the donkey ended up on his back like a beetle with his legs in the air. And then the very same thing happened again after the British had gone and the Irish started fighting among themselves, because that’s what they had learned from the British. Then one day they had to leave the house a second time when Irish Free State soldiers said they would burn it down, because they were sure they saw IRA snipers in the upstairs window.

‘There will be no more fighting and dying,’ my father says. He wants no more people put out of their houses, because it’s time to live for Ireland and stop arguing among ourselves over stupid things. He says there are too many things to do and too many places to see in Ireland like the round tower in Glendalough and the new IMCO building that looks like a white ship when you pass it by on the bus. My father pays the fare in Irish and sometimes when the bus turns around the corner you think you’re going straight into a shop window. We go to the zoo and have a picnic in the Phoenix Park with a big spire in the distance called the Wellington Monument. We run across the grass, but we’re not allowed to play on the monument because it’s something the British left behind and forgot to take with them. Wait till we get our own monuments, my father says.

There are parts of the song, too, that my father will not tell us anything about. Some of the verses are to do with the town of Leap and things he doesn’t want to remember. Like the picture of the sailor over the mantelpiece. Or the people in the town who used to laugh at him for having a father who fell and lost his memory in the navy. It was a bad thing to have a mother who was still getting money from the King of England. So they called him names and said he would never be able to jump across the gorge.

‘Every curse falls back on its author,’ my father says.

He promises to bring us to see his own home town, but he never does. Instead, he would rather show us the future, so that’s why there are verses of the song he leaves out altogether. He lost his memory when he was small and vowed instead that he would be the first person who really leaped over the gorge since O’Donovan did it. He said they were not beyond British law as long as they were still depending on Britain for their jobs and still speaking English. So when the time came, my father jumped. He didn’t emigrate or drink whiskey or start making up stories either. Instead he changed his name and decided never to be homesick again. He put on a pioneer pin and changed his name from Jack to Seán and studied engineering and spoke Irish as if his home town didn’t exist, as if his own father didn’t exist, as if all those who emigrated didn’t exist.

There are things you inherit from your father, too, not just a forehead or a smile or a limp, but other things like sadness and hunger and hurt. You can inherit memories you’d rather forget. Things can be passed on to you as a child, like helpless anger. It’s all there in your voice, like it is in your father’s voice, as if you were born with a stone in your hand. When I grow up I’ll run away from my story, too. I have things I want to forget, so I’ll change my name and never come back.

My father pretends that England doesn’t exist. It’s like a country he’s never even heard of before and is not even on the map. Instead, he’s more interested in other countries. Why shouldn’t we dance with other partners as well, he says, like Germany? So while he was still at university he started learning German and listening to German music – Bach and Beethoven. Every week he went to classes in Dublin that were packed out because they were given by Doctor Becker, a real German. He knew Germany was a place full of great music and great inventions, and one day, he said to himself, Ireland would be like that too, with its own language and its own inventions. Until then, he said, Ireland didn’t really exist at all. It only existed in the minds of emigrants looking back, or in the minds of idealists looking forward. Far back in the past or far away in the future, Ireland only existed in songs.

Then he started making speeches. Not everybody had a radio and not everybody could read the newspapers at that time, so they went to hear people making speeches on O’Connell Street instead. The way you knew that people agreed with what you were saying is that they suddenly threw their hats and caps up in the air and cheered. The biggest crowd with the most amount of hats going up was always outside the GPO for de Valera. Some people had loudspeakers, but the good speakers needed nothing, only their own voices, and my uncle Ted says the best of them all was further up the street, a man named James Larkin who had a great way of stretching his arms out over the crowd.

My father wouldn’t throw his hat up for anyone, so he started making his own speeches at the other end of the street with his friends. They had their own newspaper and their own leaflets and a party pin in the shape of a small ‘e’ for Éire: Ireland. He said it was time for Ireland to stand up on its own two feet and become a real country, not a place you dreamed about. The Irish people spent long enough building stone walls and saying the opposite. There were no rules about starting a new country and he wasn’t interested in saying what everybody agreed with either. He had his own way of bringing his fist down at the end of a sentence, like he was banging the table. Hats went up for him all right. He had the crowd in his pocket when he put his hand on his heart, and he could have stolen all the flying hats from de Valera and Larkin and Cosgrave, but he started speaking in Irish and not everybody understood what he was saying.

One day he bought a motorbike, a BSA, so he could drive all around the country making speeches in small towns. Up and down the narrow roads he went, with his goggles on and his scarf flying in the wind behind him and the music of Schubert songs in his ear. He said Ireland would soon be like Germany with its own great culture and its own great inventions. He told them Ireland could never fight with the British in a war against Germany. Sometimes he stopped to say a prayer if there was a shrine by the roadside. Or to speak to somebody in Irish. And sometimes he had to stop because of cattle on the road, until the farmer cut a passage for him through the middle and the big cow faces got a fright and started jumping to escape in all directions from the noisy new sound of the motorbike driving through.

And then my father had the big idea of bringing people from other countries over to Ireland. After the war was over he met my mother in Dublin and decided to start a German-Irish family. He was still making speeches and writing articles for the newspaper and going around on his motorbike wearing goggles. But what better way to start a new country than marrying somebody and having children? Because that’s what a new country is, he says, children. In the end of it all, we are the new country, the new Irish.

So that’s how the film ends and the song goes on. My mother never imagined meeting someone, least of all an Irishman who could speak German and loved German music. She never imagined staying in Ireland for good, talking about Irish schools or making jam in Ireland and picking out children’s shoes. My father asked her if she was willing to accompany him on a walk and correct his pronunciation. And because Germany had such great music, he wanted to tell her something great about Ireland, about St Patrick and about Irish history and Irish freedom. He told her he was not afraid to make sacrifices. He spoke quickly, as if he was still making a speech and people were throwing their hats up in the air by the thousands and didn’t care if they ever came back down again.

My mother said she had to go home to Germany because that was a country that had just got its freedom, too, and had to be started from the beginning. He would not emigrate or leave his own native shores. He said he had bought a house that was not far away from the seafront. There were no pictures on the walls yet. There was no furniture, only a table and two chairs in the kitchen and a statue of the Virgin Mary. At night, you could be lonely and you’d miss your people because it was so quiet and so empty, just listening to the radio with a naked light bulb in the room and the wallpaper peeling on the walls. But in the end of it all, you would be starting a new republic with speckled Irish-German children.

They got married in Germany at Christmas. It all happened very quickly, because you had to do things immediately, without thinking too much. She didn’t get a white dress but she got snow instead, thick silent snow. They went on the train together along the Rhine. They talked about the future and he said she would always be able to speak German in her own home. She said she would try and learn Irish, too. The children would be dressed for Ireland and for Germany. She said she was good at baking and telling stories. He said he was good with his hands. He said he would buy a camera so he could take lots of photographs, and she said she would keep them in a diary along with their first locks of hair. She said she would write everything down, all the first words and the first tears and everything that was happening in the news around the world.

There were things they didn’t talk about. She kept her secret and he buried his past as well. He hid the picture of his own father in the wardrobe. He didn’t want to offend her, having photographs of a British sailor hanging in the house. But she had nothing against England. It was not a marriage against anything, but for something new, she said. My mother even invented a new signal so that we would never get lost. A whistle made up of three notes, two short notes dropping down to one long note, like a secret code that no other family in the world would recognise.

They went to a mountain in each country. And no two mountains could be any more different. First they went to the famous Drachenfelz, right beside the River Rhine. They stayed in the hotel at the top and had breakfast looking out across the river below them, at the barges going up and down without a sound, like toy boats. She collected the train tickets and hotel receipts, even the thin decorated doilies under the coffee cups. Everything was important and would never be forgotten. She would not forget the smell of the sea either, or the smell of diesel fuel, or the faces of Irish people on the boat coming across to Ireland. They went up to a famous mountain in Ireland called Croagh Patrick to pray. It was a much harder mountain to climb and some people were even going up in their bare feet, with sharp rocks all along the path. At one point the wind came up so quickly they had to hold on to the rocks with their hands. There was no cable car. There was no hotel at the top either, where you could have coffee and cake. But when they reached the small church at the top and heard the voices of people praying the rosary together, there was a great view. They looked back down at the land all around them, with tiny houses and tiny fields and islands going out into the Atlantic.

Six (#ulink_2076590a-9694-58b9-a868-3ff9d95df6d8)

Inside our house is a warm country with a cake in the oven.

My mother makes everything better with cakes and stories and hugs that crack your bones. When everybody is good, my father buys pencil cases with six coloured pencils inside, all sharpened to a point. I draw a picture of the fox with blood around his nose. And Franz draws a picture of the house, with everybody in separate rooms – Vati, Mutti, Franz, Hanni and Maria, all standing at different windows and waving. Áine is gone away to London. The O’Neills are gone away, too, so there’s no chopping wood and no English and everybody in our house is in the same country, saying the same words again.

It’s Sunday and there’s a smell of polish on the floor. There is a smell of baking and ironing and polish all over the house, because Onkel Ted is coming for tea. Onkel Ted is my father’s brother, a Jesuit priest, and he comes to visit us after his swim at the Forty Foot. His hair is still wet and combed in lines. He once saved my father’s life, long before he was a priest, when they were still at school and used to go swimming down in Glandore, not far from where they lived. My father started drowning one day so his younger brother had to jump in in his shirt to rescue him. Afterwards my father couldn’t speak because he was shivering for a long time. But we don’t talk about that now. Onkel Ted can speak German, too, but he doesn’t say very much and my mother says he’s not afraid of silence. So he listens instead and nods his head. I tell him that Franz has shadows around his eyes because he fell off the wall and broke his nose, but my mother says we won’t talk about that now. My mother is trying to prove how decent and polite the Germans are and Onkel Ted is trying to prove how decent and polite the Irish are. And then it’s time to reach into his jacket pocket for the bag of sweets and we can have two each and no more.

Outside our house is a different place.

One day my mother let us go down to the shop on our own, but she gave us a piece of rope and told us all to hold on to it so we would not get separated. An old woman stopped and said that was a great way of making sure we didn’t get lost. My mother says we’re surrounded by old women. Miss Tarleton, Miss Tomlinson, Miss Leonard, Miss Browne, Miss Russell, Miss Hosford, two Miss Ryans, two Miss Doyles, two Miss Lanes, Mrs Robinson, Mrs McSweeney and us in between them all. Some of them are friendly and others hate us. Some of them are Protestant and others are Catholic. The difference is that the Protestant bells make a song and the Catholic bells only make the same gong all the time.

You have to be careful where you kick the ball, because if it goes into Miss Tarleton’s garden next door you’ll never get it back. She told us not to dare put a foot inside her garden. Mrs McSweeney is nice and calls you in for a Yorkshire Toffee. The two Miss Lanes across the road have a gardener who wanted to give you back the ball one day but he couldn’t. He came to the gate, ready to hand it back, but then one of the Miss Lanes appeared at the window and shook her head. The gardener stood there, not knowing what to do. We begged him please to give it back quickly before she came out, but he couldn’t because he was working for Miss Lane, not for us, and she was already at the door saying, ‘Give that ball here.’ She said she was going to ‘confiscate’ it. We stood at the railings until Miss Lane said: ‘Clear off. Away from the railings. Go on about your business, now.’

My mother laughs and says ‘confiscate’ doesn’t mean kill or stab with a knife. It just means taking control of something that belongs to somebody else. One day I confiscated my brother’s cars and threw them over the back wall into Miss Leonard’s garden, but we got them back. One day Miss Tarleton declared a football amnesty and we got nine balls back, some of which never even belonged to us in the first place and most of which were confiscated all over again very shortly after that. Miss Tarleton might as well have handed them straight over to the Miss Lanes. My mother wants to know if the Miss Lanes play football in the kitchen at night. And she wants to know what the Miss Lanes have against her, because they just slammed the door in her face.

My mother says maybe they still hate Germany, but my father says they hate their own country even more. He says they still think they’re living in Britain and they can’t bear the sound of children speaking German on the street and, even worse, Irish. My mother says that means we have to be extra-nice to them, so they don’t feel left out. You have to try not to throw the rockets up so high because the bang frightens old women and makes them think the Easter Rising is coming back again. You have to make sure the ball doesn’t go into their garden. My father says it’s your own fault if you lose the ball, because their garden is their country and you can’t go in there. He says our country is divided into two parts, north and south, like two gardens. He says six counties in the north have been confiscated and are still controlled by Britain. The difference between one country and another is the song they sing at the end of the night in the cinema and the flag they have on the post office and the stamps you lick. When my father was working in the north of Ireland once, in a town called Coleraine, he refused to stand up in the cinema because they were playing the wrong song. Some people wanted to put him against the wall and shoot him. And then he left his job and came back to his own country where he could speak Irish any time he liked.

So, you have to be careful what country you kick your ball into and what song you stand up for in the cinema. You can’t wave the wrong flag or wear the wrong badges, like the red poppies with the black dot in the middle. You have to be careful who to be sad for and not commemorate people who died on the wrong side.

My father also likes to slam the front door from time to time. And he’s the best at slamming doors because he makes the whole house shake. Lots of things rattle. Clocks and glasses and cups shiver all the way down to the end of the street when my father answers the door. He sends a message out all over the world, depending on who knocked. If it’s the old woman with the blanket who says ‘God bless you, Mister’, and promises to pray for him and all his family, if it’s the man who sharpens the garden shears on the big wheel or if it’s somebody collecting for the missions, then he gives them money and closes the door gently. If it’s people selling carpets he shakes his head and closes the door firmly. If it’s the two men in suits with Bibles then he slams it shut to make sure not even one of their words enters into the hall. And if it’s one of the people selling poppies, then he slams it shut so fast that the whole street shakes. Sometimes the door slams shut in great anger of its own accord, but that’s only because the back door has been left open and there’s a draught going through the house.

One day Mr Cullen across the street asked us to help him wash his car. Afterwards he gave us a whole chocolate bar each, because he works for Cadbury’s and has boxes and boxes of chocolate bars and Trigger bars in the boot of his car all the time. A woman came along the street selling the red badges with the black dot in the middle, so, as well as the chocolate, he bought us each a badge and pinned them to our jumpers. Lots of people on the street were wearing them – Miss Tarleton, Mrs Robinson, Miss Hosford, and the two Miss Lanes.

We didn’t know they were wrong. We didn’t know that wearing the wrong badge was like singing the wrong song in the cinema. So when my father saw us coming into the house wearing poppies, he slammed the door and all the clocks and cups and saucers shivered. Franz shivered too. My father ripped the poppies off so fast that he stabbed his own finger with the pin and I thought the badge was bleeding. He ran into the kitchen and opened the door of the boiler and threw the badges into the fire. Then he ran his finger under the tap and looked for a plaster while the badges burned to nothing and I thought it was a big waste because Mr Cullen had paid money for them.

‘Who gave you those damn things?’ my father wanted to know.