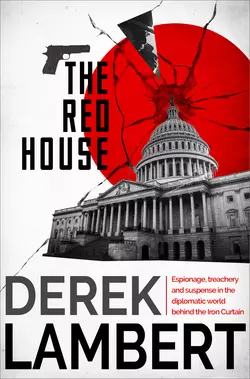

The Red House

Derek Lambert

A classic Cold War spy story from the bestselling thriller writer Derek Lambert.The Red House follows a year in the life of Russian diplomat Vladimir Zhukov, the new Second Secretary at the Soviet Embassy in Washington – a ‘good Communist’ in 1960s America.Seeing what life in the West is really like, he discovers there is more to America than what Soviet propaganda has taught him. Increasingly intrigued by the Washington circuit, from outspoken confrontation between diplomats to the uninhibited sexual alliances arranged by their wives with other diplomats, the capitalist ‘poison’ begins to work on him and his wife.As he struggles to remain loyal to his country and begins to question who is the real enemy, he has to decide to whom is first loyalty due: country or lover, party or conscience.‘A gripping and topical novel’ Reading Chronicle

THE RED HOUSE

Derek Lambert

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_41170289-092b-5ef4-9923-ad366c5f8f4a)

Collins Crime Club

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by Michael Joseph Ltd 1972

Copyright © Derek Lambert 1972

Design and illustration by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Derek Lambert asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780008268343

Ebook Edition © November 2017 ISBN: 9780008268336

Version: 2017-10-04

DEDICATION (#ulink_f939736f-6c30-5791-ba0c-504668039f18)

to

Blossom with love

MANY good people helped in the preparation of this novel. They know who they are and I thank them. In particular I wish to express my gratitude to Brian and Nelli Hitchen and Gordon Lindsay who provided shelter. To Ross Mark who introduced me to Washington. To Peter Worthington who introduced me to a defector. And to Donald Seaman, my mentor.

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#ulink_f4a95759-4d5d-5408-a7e1-585baf0ba5de)

THE period is 1968. A year that embraced the assassinations of a black and a white leader, a space-shot, the election of a new American president, race riots of unprecedented fury, the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia. A savage, tragic, momentous year. In the interests of the narrative I have jockeyed a few dates, a few occasions, a few moods, and I apologize to any students of contemporary history who may be offended. It should also be noted that some of the speeches in the sequence dealing with an actual meeting of the United Nations Security Council are interpretations published by the U.N. and not precise translations.

CONTENTS

Cover (#ua3cb28eb-30c0-5455-870f-b07f4bfc9928)

Title Page (#u01b893f2-e80a-5f55-80ef-4217be0cf918)

Copyright (#ulink_aa18601d-511c-5953-8c0d-e9b37db7ebd9)

Dedication (#ulink_b36d9a80-646f-5b70-a7a5-83771ce6109f)

Author’s Note (#ulink_9f6970ae-9464-56f4-be69-aabd8a014104)

Part One (#ulink_2cdcdd71-fb56-5258-8deb-0be2723dd3b2)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_682c6dd2-e4c6-578e-a401-f3e5219b7e9c)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_6702253e-64c8-5569-adb1-ddd09c2dc28c)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_189851c9-1198-58a4-8996-7699b56f6f9e)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_0266603d-5a8e-5f2d-9e74-20732e99a6c7)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_674663c4-5a85-5987-9d8a-f890dc9b4fcb)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_5f88a736-f144-56d4-a198-61a004e209ad)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#ulink_fc4a7e3f-fcef-521f-b0d5-c4c1cd2df46b)

1 (#ulink_636f2985-b2ce-5bb0-8b82-0ba0e155a3f2)

SEVEN a.m. on New Year’s Day. Beneath the aircraft the lights of Long Island probed the sea with disciplined jewelled fingers. The lights of Moscow, Vladimir Zhukov thought, had been more abandoned: scattered nebuli of milky neon. Symbolically, the lighting plans of Capitalism and Socialism should have been the other way round.

Zhukov swallowed his vodka as if it were the last drop of Mother Russia’s milk: there had been many vodkas on this special II-62 flight from Moscow to New York.

Beside him his wife closed her handbag with the finality she instilled into most movements. ‘Please excuse me,’ she said, standing up.

‘You are going to prepare yourself to meet the decadent, bourgeois imperialists?’

‘I am more concerned with making myself presentable for the representatives of our embassy.’

‘It was only a joke,’ he told her retreating figure as it stumbled, uncharacteristically, with the descent of the aircraft. He watched her with affection, then moved into her seat.

The affection melted into many emotions. Expectation, curiosity, pride at what he represented. And a vague, uncertain apprehension, as cold and disquieting as a first snowflake smudging the window of a warm and complacent room.

He gazed down at the avenues of lights, the pastures of snow luminous in the darkness, the black oil of the sea extinguishing the lights. Coney Island? Long Beach? The old movies on which most assessment of America was based—forgetting propaganda for the moment—had another revival in the auditorium of his mind. Jack Oakie, Alice Faye, George Raft. Cops with caps and nightsticks, black shoeshine boys, double-breasted suits with lapels as flat as cardboard, leaning tenements and jostling skyscrapers, ice-cream sodas, bourbon on the rocks, girls with lovely legs and afterthought faces, the drawling south and the snapping north, sub-machine guns, King Kong. That’s my America, that’s the America of the most humble apple-picker in Kazakhstan. There it is spangled beneath me. True or false?

And, returning inevitably to the propaganda, he thought: New York—the fount of decadence, the blood-bank of criminal aggression. True or false?

Vladimir Zhukov, aged forty-four, newly-appointed second secretary at the Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in Washington, gripped his empty finger-greased glass tightly and regarded the accelerating reality with awe.

His wife returned smelling faintly of Russian cologne. The smell of our soap, our pomade, our scent. The smell of the audience at the Bolshoi. Turn the serpent head of the aircraft around and fly it back to Moscow. New Year’s celebrations—the children with presents from the toyshop in Kutuzovsky, Kremlin parties with clowns and storytellers, Georgian wine, Stolichnaya vodka, bearhugs, skating in Gorky Park, women singing with lemon-juice in their voices. From his pocket he took a New Year’s card—foreigners in Moscow sent them as Christmas cards—and examined the Kremlin. Two red stars and a flag perched on pencil-sharpened spires and golden baubles. Plus the new Palace of Congress completed in 1961 and seating 6,000, his statistical mind recalled. And somewhere in the centre of this symphony of architecture the big growling bears.

He glanced at his wife in case she was listening to his thoughts. But she was busy fastening her safety belt, pleating the waist of her black suit inside it.

Vladimir Zhukov said, ‘We’re fortunate to be flying direct to New York, instead of Montreal.’

‘We’re very fortunate,’ Valentina Zhukova agreed.

He patted her hand because of adventure shared and she smiled with a glint of gold; the glimpse of sunlight she sometimes regretted.

‘Do you feel nervous?’ he asked.

‘Not at all. You shouldn’t either.’

‘I didn’t say I was,’ he lied.

‘But you aren’t completely happy at the prospect of our arrival.’

He shrugged his big torso. Over-shrugged. Who would ever suspect the fragility inside such a big frame? The poetry drowning in statistics. His stomach rumbled as the vodka passed on, depositing the last of the alcohol into his blood.

Valentina said, ‘You shouldn’t have drunk so much.’

‘It’s the first day of the new year. Back home we’d be celebrating and Natasha would be singing to us in our apartment.’

‘Are you sure you didn’t drink to give yourself courage?’

Did a man of his stature need liquor to armour-plate his guts? Would the Party have permitted such a ‘degenerate’ to be posted to Washington, the enemy capital? Only Valentina could have asked such a question: only a wife with nocturnal knowledge, only a wife observing after sex, after a loss, after disappointment … ‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ he said.

‘I’m sorry.’

He held her hand. ‘Let’s feel this together. Would you have dreamed when we first met that one day we’d visit America together? Even now I find it hard to believe that Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx are down there.’

Mickey Rooney, the East Side Kids, Al Capone, organ-grinders with monkeys on their shoulders. Upton Sinclair, Sinclair Lewis, Steinbeck, Dreiser, Mark Twain.

‘I know what you mean,’ she said, leaning across him to look down, her large breasts comfortable against his chest.

‘Africa wouldn’t have this effect on me. Or China or India. But this … I don’t think I really believed it existed. All those tourists in Moscow, those unlikely diplomats, those businessmen. All straight out of the movies.’

The lights swarmed up on them, streaking past the windows. The half dozen passengers on the jet loaded with provisions and equipment for the embassy in Washington and the Mission to the United Nations in New York waited for the landing with theatrical nonchalance or honest rodent fear. A bump and the lights were slowing, the white ranches of Kennedy International Airport braking. Dawn began to ice the skyline.

Ponderously the plane trundled towards the New World. The stewardess, plum-plump in threadbare blue, stood up and peered out of a window as if she were hoping it were Khabarovsk or Leningrad. The passengers pointed, nodded; the aircraft stopped.

Inside reception it was a bewilderment of glass, marble, neon, plastic. Negro porters, movie voices, no guns that Vladimir Zhukov could see. His head ached at the base of his skull and a vein throbbed on his right temple.

Somewhere a man addressed another as ‘pal’ and was, in turn, referred to as ‘a lousy sonofabitch’. He had arrived. He was in America.

Or was he? Two men wearing grey fedoras and black overcoats with clothes-hanger shoulders came up. ‘Good morning, Comrade Zhukov,’ one said. ‘Welcome to New York.’

Nicolai Grigorenko occupied half the front seat of the black Oldsmobile, his companion and the driver the other half. Grigorenko was a large man, Siberian-faced, not unlike Brezhnev, ponderous but authoritative, a chain-smoker, fiftyish, throaty. One of the growlers. Mikhail Brodsky was a sapling by comparison; soft-haired, smiling, with a cold lodged high up in his nose, gold-rimmed spectacles, nervous hands and a habit of prefacing answers with two sing-song chords. Uh-huh—D flat rising to E flat.

The Growler spoke. ‘Ordinarily we would have driven direct to La Guardia and boarded the shuttle to Washington. But there’s a blizzard in Washington and you’ll have to stay the night at the mission in New York.’

Excellent, Zhukov thought. Everyone should spend their first night in America in New York. ‘What is this shuttle?’ he asked.

‘It’s like a regular bus service. You buy your ticket on board.’

‘That sounds very progressive,’ Zhukov rashly observed.

The silence in the car throbbed.

Grigorenko turned his big polluted face around. ‘You will learn, Comrade Zhukov, that much of what appears to be progress in this country is achieved at the expense of far more deserving causes.’

Brodsky removed a bullet-shaped inhaler from one nostril and hummed a two-bar introduction. ‘An Aeroflot pilot would not have been deterred by the sort of blizzards they have in Washington.’

Zhukov leaned back in his seat and, with two fingers on the vein in his temple, observed the approaches to New York.

With the deep snow on the ground and flakes peeling off the sky it might have been Sheremetyevo Airport. Even a few pine trees on the perimeter. Except for the cars. Acres of them bonneted in white in a parking lot. In Moscow it took more than a year to get delivery of a stubby little Moskvitch or a Volga of ugly and ancient design at prices few could afford. Automobiles, he told himself, are my first impression. Uniform, luxurious, decadent, asleep in the comfortable snow. But so many … Did anyone walk?

Grigorenko followed his gaze or tuned in to his thoughts. Perhaps one day they would even achieve that. He pointed up to the sagging sky. ‘It’s the automobiles that cause the pollution. Every year it kills thousands of old people in New York City. It’s typical of the American mentality that comfort of the middle-classes should take precedence over the welfare of the aged.’

‘The senior citizens,’ Brodsky hummed. And giggled.

Grigorenko continued his recital while Zhukov thought briefly of the pollution over Kiev and decided not to make the comparison. He was a second secretary and his guides were inferior in rank. But not, he guessed, in that other hierarchy in which a third secretary could outrank a Minister Counsellor. Perhaps even an ambassador.

The houses on the left looked English; dozing villas alive inside with occupants preparing for breakfast. Silver buses and ruthless trucks spraying the windscreen with brown slush; highways wheeling and diving beneath each other; wires and roads and signs glaring and guiding. The mind panicking a little; the panic masked by the impassive trained exterior.

Grigorenko, official Soviet guide on the nursery slopes of first impressions, turned again. A single hair grew from the end of his suet nose. ‘You have been celebrating on the aircraft, Comrade Zhukov?’

‘It is the first of January.’

‘Certainly. And there will probably be a small celebration in New York. But it was, perhaps, a little unwise to drink so early in the morning?’

‘You lose all sense of time between Moscow and New York.’

‘True.’ The big puppet head nodded slowly.

Valentina squeezed Zhukov’s hand. ‘Look, Vladimir.’

Ahead, Manhattan assembled itself in the young, snow-tattered light, blurred coyly then reasserted itself—a postcard so familiar that it was again difficult to accept the reality.

Grigorenko isolated the Empire State from the rest. ‘The world’s tallest TV tower,’ he said reluctantly.

‘That’s correct,’ Zhukov agreed without thinking. ‘And the whole building weighs 365,000 tons—that’s fourteen tons to support each occupant.’

Grigorenko glared at him suspiciously. ‘You seem to know a lot about one American building? Perhaps it’s you who should make the introductions.’ He felt for the hair on his nose.

‘Not just one American building. The most famous of all. I read my tourist literature. And,’ he apologized, ‘I have this facility with figures and statistics. They lodge in my brain.’

Which was true. There was Manhattan, floating as serene as a reflection, and he had to toss 365,000 tons of concrete into it. Such training.

‘It’s very impressive,’ Valentina said. ‘Especially beside all this’. She pointed at some grubby miniatures along the road.

‘Uh-huh.’ Brodsky tuning-up. ‘But it seems to me that we should not forget the squalor and corruption that exists behind those façades. Drugs, drunkenness, violence, vice.’ He ticked them off on the fingers of his dogma, his voice lingering and slavering over V-I-C-E.

Only the driver said nothing, and Zhukov wondered how his young peasant brain reacted—if his training had left him with any reactions.

I want to feel and savour it by myself, Zhukov thought. I want my own private instincts which I have so carefully and privately nurtured. To feel and judge and file.

They lingered beneath a red light before entering the Kremlin of Capitalism.

Manhattan’s streets and avenues opened up and the sky narrowed—grey canals high above. He saw a Hollywood cop feeling his nightstick as if it were a damaged limb and thought of the Soviet militia with their dramatic topcoats and irritable toothpick truncheons. Discovery and nostalgia fought each other. Steam billowing from vents in the city’s bowels and lingering in the icy, lacy air: felt boots crunching fresh snow on Arbatskaya Square.

Discovery won the battle without deciding the war; the shops the stormtroopers. Windows of nonchalant plenty. Furniture in theatrical sets, beds of jewellery and dormant watches, racy clothes and gossamer fabrics, skis and golf-clubs, package tours to Las Vegas, Miami, Dublin or Tokyo, a coffee carafe of Pyrex and silverplate like a contemporary samovar, beckoning beds, busty, gutsy displays of brassieres and corsetry, a garden window with simulated grass being cut by a mower (plan ahead for summer), Tsarist perambulators, floors of shoes ready to quick-march, toys Russian children couldn’t dream of because they couldn’t imagine them. Everything cheaper than everything else, every store flaunting infinitesimal advantage.

And the Christmas tableaux in cavernous windows. Dwarfs and children and fairies strutting and dancing and blessing; a carousel carrying dizzy teddy-bears; a rocket bound for the moon with Santa Claus (Grandfather Frost) astride the command nodule. And Christmas trees (yolka) buttoned on to the haunches of the elephantine buildings with white electric bulbs.

Grigorenko interrupted as he had done with many other newcomers. ‘I know just what you are thinking.’

‘You do? You presume too much, comrade.’

‘You are wondering what can be wrong with Capitalism if it produces so many fruits.’

The vein had subsided, the ache at the base of his skull fading. ‘Is that what you wondered when you first arrived?’

Grigorenko’s pattern was disturbed. ‘Not I. But you. Is that not what you are thinking?’ The growl lost a decibel of menace. Brodsky felt the bridge of his sinus and made a noise that could have been a simper, a giggle or a sneeze.

Zhukov said it wasn’t, enjoying the transient authority of unexpected attack. He was, after all, a second secretary.

‘Then what are you thinking?’

‘Just remembering that in the shops in Gorky Street you can see nothing in the windows.’

‘You are commenting unfavourably on the commerce of the Soviet Union?’

‘On the contrary, Comrade Grigorenko. I’m surprised that you should interpret a remark so prematurely and so incorrectly.’ He gestured towards a windowful of lingerie threaded with tinsel. ‘If you judge a woman by her jewellery you may find a whore.’

‘Just so, comrade.’ Grigorenko made notes in his mind. ‘You speak very well—but of course that’s your job.’

‘Surely yours as well, comrade.’

Valentina’s elbow nudged his ribs, warning.

Brodsky said, ‘Perhaps Zhukov’s words are as empty as those shops in Gorky street.’

Zhukov said, ‘But the shops aren’t empty. Only the windows.’

‘You will make a very good diplomat,’ Grigorenko observed. ‘You’re smart with words.’

‘I am a good diplomat.’

‘Forty-four? Second Secretary? Perhaps your capabilities have been underestimated.’ The doggy face regarded Zhukov with total seriousness; in the bruise-coloured pouch under one eye there was an incipient growth.

If I were a man, Zhukov thought, I’d reply, ‘But you’re only a third secretary.’ But you had to be smart with not saying words as well as saying them.

The city was slowly on the move, the snow like the fuzz the morning after too much Stolichnaya.

A Buick fanning wings of slush hove past bearing the legend ‘Save Soviet Jewry.’

From what? Ah, diplomacy …

A street sign said Tow Away Zone. Another said Snow Emergency Street. They turned into East 67th Street. No. 136—The Mission of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to the United Nations. And those of Ukraine and Byelorussia. And, across the road, down the street from the red-brick 19th police precinct clubhouse a synagogue.

2 (#ulink_5de8858c-705d-5773-a510-d8947e8b6357)

BUT the spirit of good will and New Year’s resolution hadn’t penetrated the pale and clinical building at 136.

In the foyer Zhukov’s body turned clammy in the artificial heat. A woman with greying hair forced into a bun, and a lackey in a miserable suit and thin tie regarded him suspiciously. A plastic Grandfather Frost and the Snow Maiden beamed in the corner in spite of it all.

‘We shall stay here until they open Washington Airport,’ Grigorenko said. ‘You would perhaps like to get some sleep?’

‘I’d like to have a look at New York while I’m here,’ Zhukov said.

‘It would be better if you got some sleep.’

‘I should like to see New York. It might be my only chance.’

Valentina sided with Grigorenko. ‘I’m very tired, Vladimir.’

You couldn’t make a scene within minutes of arrival; nor could you relinquish all authority to a couple of third secretaries protected by the ghost of Beria. ‘Perhaps later,’ Zhukov said.

Outside they heard scuffling. Russian oaths involving mothers. A voice with a Uzbek accent screaming ‘Samarsky!’

The door sprang open. A blast of cold air followed by a young man held by two squat captors. They pinioned him easily, his feet just touching the ground. His hair was black and curly, badly cut; his skin dark, his body slight and struggling.

Grigorenko strode across to them and growled as softly as he could, showing the squatter of the two an identification card.

Grigorenko spoke to the young man.

‘Go and fuck yourself,’ screamed the young man. His dark face was frenzied with fear—a man being carried to the hangman’s noose.

Grigorenko nodded slowly, as if abrupt movement might dislocate the big head from his neck. ‘Put him down.’ The hunters released their quarry. ‘You haven’t made a very good start on the New Year,’ he observed.

‘Shit on you,’ said the prisoner.

Grigorenko stepped forward kicking hard and down the shin, crunching on the instep, bringing his knee up into the crotch as the man gasped forward, finally rabbit-punching the side of the neck with the blade of his hand.

The young man, doubled over in pain, was carried away.

‘Tomorrow,’ Grigorenko said, ‘he will be on the plane to Moscow.’

‘And what was that all about?’ Zhukov asked.

‘It’s nothing for you to worry about,’ Grigorenko replied.

Brodsky, who’d been watching with his inhaler held up one nostril, said, ‘Just another drunk, probably. They will insist on drinking Scotch when they’re used to vodka.’

‘That man wasn’t drunk.’

‘It affects different people in different ways.’

‘And now,’ Grigorenko announced, ‘it’s time for bed.’

He was, Zhukov thought, very avuncular. As avuncular as Stalin.

Only Grandfather Frost who had once been on the receiving end of denunciation—a puppet of the priests, no less!—saw any humour in the situation.

He allotted himself two hours’ sleep and lay down on one of the two single beds in the small bedroom. A bowl of fruit and a picture of Lenin dominated the decor.

He listened to his rapid vodka heartbeat and told himself to calm down about everything. About the priorities shifting around in his mind. About the tests of loyalty ahead.

Although I am a good citizen, Vladimir Zhukov assured himself. A good Party member. I believe in our crusade. His trained brain recited, unsolicited: ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.’ The last lecture in Moscow surfaced. ‘We know that an accelerating, unmanageable national debt will effect civil collapse and open the floodgates of Socialism.’ The lecturer’s fanatic face peered closer. ‘This is now happening in the United States of America. It is up to you …’

They had observed him over the past five years and he had passed their surveillance. Not for them to penetrate the secret sensibilities that are a man’s soul. The coil of poetry unsprung. Not for them to glimpse the doubts on which true strength is founded.

He lapsed into an excited doze, limbs twitching, eyelids quivering. Yellow cabs vanishing down narrowing vistas of skyscrapers, Manhattan a mirage behind a veil of snow. When he awoke he was confused about reality: he had dreamed so often about this arrival in a celluloid city projected on his private grey screen.

He climbed out of bed carefully, still in his underwear. It was exactly two hours: such damned precision. His wife slept serenely. Through a slit in the curtain he looked down on the synagogue, on the blue cap of a guardian cop.

In the bathroom down the corridor he shaved, drawing blood from his tired skin. He pressed his eyelids and his eyes ached back at him. He massaged a little pomade into his sleek hair and watched the wires of silver fade. He returned to the bedroom.

Valentina said, ‘Where are you going, Vladimir?’

‘I thought I’d take a stroll. I can’t sleep.’

‘You mean you’ve stopped yourself from sleeping.’ She knew him so well.

‘I may never see New York again.’

‘They don’t want you to go out alone, Vladimir. You know that. Why defy them on our first morning in America?’

‘I’m not their slave, Valentina.’

‘Don’t be foolish—remember how you’ve worked for this day.’ She sat up in bed, hair loose, the brown aureoles of her nipples visible through white cotton; in her waking moments she was more feminine than she cared to be.

‘A servant, maybe. But, I repeat, not a slave. I must assert some authority now before it’s too late.’

‘Come and lie down with me.’ She stretched out warm arms.

Vladimir Zhukov silently apologized to his wife for rejecting her comforts and put on his new dark-grey suit with the wide trouser bottoms which Western fashion was beginning to acknowledge. Except that with his trousers the width extended to the thigh.

Valentina said, ‘If you insist, then I shall come with you.’

But he wanted to see it by himself. Gary Cooper walking lone and tall down Fifth Avenue. Compromise—the dress-sword of the diplomat. ‘I’ll meet you later and we’ll have lunch together.’

‘Meet me? Where? We don’t know anywhere in New York.’

He reacted swiftly. ‘At the top of the Empire State Building.’ He laughed aloud for the first time since the aircraft touched down at Kennedy Airport.

He felt as if he had been released from prison and was vaguely ashamed of his exhilaration. But a lot of conformity lies ahead, comrade.

It was midday. The snow had stopped and the sky above the rooftops of Lexington Avenue was polished blue. A few jewels still sparkled on the edge of the sidewalk but in the gutters the slush was ankle-deep. They had a lot to learn about street cleaning, he decided proudly.

The Gallery Drug Store, Marboro Books. Sixty, 59, 58 … 53, 52. He enjoyed the drugstores. ‘Meet you in the drugstore, buddy.’ Sulky-faced girls with bobbed hair wise-cracking with chunky athletes with greased or chopped hair (Hollywood 1935–50). But it needed courage to enter one. They would call him mister and ask where he came from.

Bookshops, delicatessens, restaurants … the luxury seemed cosy and refined in this particular avenue. East Side, West Side. Which was which? Grand Central Station, Central Park, Times Square, Fifth Avenue, the Waldorf Astoria, Harlem, Greenwich Village—that was all he knew.

He found courage and bought two newspapers from the front stall of a drugstore. The New York Times and the Daily News.

‘Thank you,’ he said.

‘You’re welcome,’ the girl sighed, yawning and chewing and talking simultaneously.

He tucked the papers under his arm like a baton wondering if he could be mistaken for an American. He looked behind to see if he was being followed. It didn’t look it but you could never tell.

What strikes me most? he asked himself, seeking first impressions for the album. It had to be the shops with their abundance of consumer goods: this he had been warned about—the products of exploitation, late participation in wars, geographical advantages, twenty million Soviets killed conquering the Hun. But the briefings hadn’t fully prepared him for the profusion, the multiplicity, the permutations of plenty. (How many variations of salad dressing could there be? How many odours of deodorant? and who wanted to smell of lemons or Tahitian lime anyway?) In Moscow he had queued for a ballpoint pen with a sputnik that slid up and down the stem.

And again, the cars—the automobiles. New Yorkers paraded in their cars. Vladimir Zhukov, crunching down Lexington Avenue with the enemy all about, lusted guiltily for a big tin fish with automatic drive and power-assisted windows. He was startled by the number of female drivers—girls with long, straight hair, smartly coiffured old ladies steering their vehicles like tank commanders. What happens to the babushkas? Do they have them put to sleep? or let them drive their tanks over the cliffs like lemmings?

He reached 42nd and turned right past Grand Central, remembering faintly from another life the stations of Moscow—cathedrals, fortresses, terminals of turreted grandeur where immigrant peasants wandered like bewildered insects.

He looked at the street numbers and knew with his mathematical certainty that he could never be really lost; just the same at that moment he was, gloriously and excitingly. Like a child trying to get lost and fearing the chilly second-thoughts of dusk.

Courage, comrade. He said to the cop frowning at the unplumbed depths of slush on a street corner, ‘Excuse me, please, can you tell me the way to the Empire State Building.’ His words froze and hung between the two of them.

The patrolman who had long sideburns and a squashed face said, ‘How’s that?’

Zhukov expelled the rush of words again, hating the sense of inferiority that accompanied them. Put this cop in Red Square and see how he managed.

‘Where you from, fella?’

‘Moscow.’

Enlightenment shifted the crumpled features around and Zhukov realized that it was a friendly face.

‘No kidding. One of those emigré guys, huh? And you don’t know where the Empire State is? How’s about that.’

Zhukov waited.

The patrolman said, ‘Two blocks down. Turn left down Fifth. You sure as hell can’t miss it. I guess that’s the one building you can’t miss.’

‘Thank you.’ Zhukov crossed the slush, wishing he didn’t look so conspicuous. Even though no one seemed to pay him much heed.

‘Okay, pal,’ said the patrolman. ‘Any time. Any time at all. Have a good day.’

The City Library. (Four million volumes.) Negroes, Italians, Poles, Swedes, Germans, Puerto Ricans (he presumed), hippies, producers in camel-hair coats, soldiers to be sacrificed in Vietnam, women in furs and boots as arrogant and vapid (he was sure) as fashion models, businessmen with slim black attaché cases—one there munching a hot-dog. All intent on something on this white melting day.

One thing he did not do: he did not walk along staring up at the narrow sky because that was the hallmark of the green horn. Which I am not, he thought. I am a representative of the greatest power on earth. It’s just that I’m a stranger. At which point he discovered that his head was tilting upwards like a peasant seeing his first aeroplane.

So there it was—a colossus of playbricks beneath him. Massive and vulnerable. You could crunch them, swipe them aside with one bear paw.

On the 102nd floor observatory, nicely placed at 1,050 feet, Vladimir Zhukov surveyed the enemy camp with awe and got annoyed about the awe.

He gazed south-west where the vanguard of the buildings gathered for approaching tourists. With the Statue of Liberty on sentry duty. He moved and sighted north towards what he thought was the Bronx, beyond a phalanx of skyscrapers. Difficult to believe that in one section of one storey of one of those obelisks, a business, an existence, a saga, could exist without awareness above or below.

To the north-east the metallic, ostentatious thrust of the Chrysler Building with, he surmised, the pygmy-giant of the United Nations close by; but within that cubist pygmy lay the power to curb so much capitalist expansionism.

The city, so beautifully exhibitionist, within the ice-blue perimeters of its rivers.

‘Sometimes snow and rain can be seen falling up.’

‘I know,’ Vladimir Zhukov said. ‘And the rain is sometimes red.’

He turned without surprise and faced Mikhail Brodsky.

The breakfast was called The Heavyweight. It consisted of a wafer of bacon, two rheumy fried eggs and three pancakes covered with maple syrup and crowned with a dollop of whipped cream. For your $1.25 you also got a small glass of orange juice, toast and coffee. It was, Zhukov thought, good value and totally disgusting He ate it with relish.

Brodsky ordered coffee, tapping the last grains of sugar from the paper sachet with his forefinger, leaking the last drop of cream from the tiny carton, his actions the legacy of a needy youth. Although the delicate bloom on his cheeks seemed to have surmounted bread and potatoes and blinis.

Brodsky tuned in with two bars and said, ‘I think this is more our style.’

More than what?

Brodsky cat-sipped at his coffee. ‘I feel at home in these places. With these people.’ He indicated the coffee shop’s occupants: a gaunt, white-haired man in a Stetson flirting grotesquely with the woman behind the counter; a starved little guy in a red checked lumber jacket continuing his life’s search for winners with a chewed fingernail; a bearded Negro in a cowboy jacket riding his chair like a horse; mother and son spooning banana splits, a salesman inside an overcoat collapsed by rain and snow.

The statement seemed to Zhukov to be an admission of inferiority. But he let it pass. ‘How did you find me up there?’ Either the room had been bugged or Valentina had told him or he’d been followed. Any one explanation wearied him.

‘It was not so remarkable. Your wife was still feeling tired and suggested that I meet you instead.’ He wiped his glasses, looking myopic and vulnerable. ‘And it’s good that we become friends because we shall be seeing a lot of each other in Washington. I think we should have a chat now before we leave. You see,’ he explained, ‘the weather has cleared and we shall be taking the shuttle this afternoon.’

‘So soon?’

‘Washington is your destination.’ He glanced around the café with a furtiveness as natural as sleeping and breathing.

‘So we are going to have a frank and open talk, are we?’

‘I hope so, comrade. I really hope so.’ The girlish hair fell about.

He pressed his loaded sinus with finger and thumb; nails pared and clean, hands hairless. His lashes brushed the lenses of his spectacles. He wore the same dark overcoat, the same woolly scarf that mothers made you wear, a thin grey tie.

‘Then tell me what happened at the Embassy this morning.’

‘It was all most unfortunate.’

‘I could see that. It is never fortunate for a man when he is kicked in the crotch and rabbit-punched. But why, Brodsky? Why?’

‘He was a very foolish boy.’

‘What happened?’

‘You need not concern yourself. It was a small irritating incident and you have the great task of adapting yourself to life in this self-indulgent society in which we find ourselves. It was the foolishness of youth. A girl, too much whisky—watch the whisky, comrade. He will wake up in Moscow and be dealt with there. A small punishment, probably, plus the knowledge that he has ruined his career.’

‘I think he tried to defect.’

Brodsky sighed, holding up one delicate hand as the woman came to clear the table.

‘More coffee?’ she asked.

‘Please,’ they said.

‘Coming up.’

She was blonde and Germanic and smiling, but she moved like an automaton, like the girl who sold him the newspapers. A symptom of being a menial in an affluent society, Zhukov supposed. She brought more coffee and they thanked her and she said, ‘You’re welcome.’

‘Did he try to defect?’ Zhukov asked.

‘That is a very dramatic and contemporary word. He simply decided that he would like to stay with this American girl.’ Brodsky reached for his inhaler. ‘I suppose you might as well know the full story.’ (Which meant he would be lucky to hear a half-truth.) ‘He arranged to meet an American in a café in Queens. She was going to help him disappear for a while. But we were waiting for the unfortunate Boris Ivanov in the café.’

‘You mean you made some sort of deal with the Americans?’

Brodsky shrugged delicately. ‘It really isn’t my business. I can only tell you what I have heard. He was only a boy after all. I suppose he had nothing much to offer the Americans …’ He put away the plastic white bullet. ‘Not like you, comrade. If you were ever in a position to take such foolish action.’

The song had left his lips. Replaced by the voice of secret authority that served Czars and other dictators and the Party with unswerving treachery; the voice of those who chose murder and intrigue as others choose dairy farming or quantity surveying.

And here was the voice in a coffee shop on 42nd Street, New York City. Zhukov’s reactions chilled: Grigorenko was the underline, Mikhail Brodsky the boss. Perhaps the boss, with an Ambassador, a Minister Counsellor, counsellors, secretaries, attachés under him.

‘If you think I am the sort of person who would take such an action then I should never have been sent here,’ Zhukov said.

‘I didn’t make the choice.’ Brodsky lit a mentholated American cigarette. ‘But it was very foolish of you to go wandering around in New York on your first day here.’

‘Apparently I was not alone.’

‘You could have been mugged.’

‘Mugged?’

‘Robbed, beaten up. I don’t know how the word came to be. Perhaps because only mugs allow themselves to be robbed.’

‘In broad daylight?’

‘Certainly in broad daylight. This is a dangerous and decadent society, comrade. A man will knife you in a cinema queue for the money to buy drugs.’ He leaned forward, blinking behind his gold-rimmed spectacles. ‘Like myself you are a sensitive man. You write poetry, I believe?’

‘How did you know that? It’s never been published.’

Brodsky slipped the question. ‘I too write poetry. Some of it has been published in Novy Mir. And once I wrote an amusing little poem about Russian women wearing shorts. Calling them shortiki—an American-derived term—instead of trusiki. It was quite well received.’

‘I’m happy for you,’ Zhukov said.

‘I’m trying to illustrate that people like ourselves should be both sensitive and realistic. It’s not wise to let sensitivity get the upper hand in this country. Values can become unbalanced in a sensitive mind. You can be dazzled by the abundance of food and drink and clothes and apparent freedom and forget the misery and oppression and violence.’

‘Thanks for the warning,’ Zhukov said. ‘I had many like it before I left Moscow.’

‘Nevertheless these first impressions can be quite traumatic.’ He sang a couple of bars and relaxed. ‘Now it seems to me that we should go.’

The woman behind the bar called out, ‘Goodbye, folks. Have a good day.’ And confided to her senile suitor in the Stetson, “English tourists—I can always tell ’em.’

But Mikhail Brodsky was not quite finished. ‘The safest place to talk,’ he confided, ‘is in a crowded street.’

They cut down Madison Avenue, turning right down 53rd. Zhukov looked with pleasure at the legs of the mini-skirted girls and surmised that they must have very cold arses.

Brodsky walked very carefully, despite his rubber overshoes, leaping like a ballet dancer over the street-corner swamps.

After a while Zhukov asked him what was on his mind.

‘I believe certain approaches were made to you in Moscow.’

‘Such as?’

‘About your responsibilities in Washington. Above and beyond the call of duty.’

‘They told me to keep my eyes and ears open for any information that might be useful to the Soviet Union.’

‘A delightfully euphemistic way of putting it.’ Brodsky leaped a small lake on the corner of Lexington. ‘Mr Hoover has estimated that eighty per cent of all personnel at the Soviet Embassy in Washington are spies.’ His gold glasses slipped and he pushed them back with his woolly-mittened hand. ‘Who would have thought that the great Mr Hoover would have indulged in such understatement?’

While he was waiting for Valentina to powder her nose Zhukov flipped through the Manhattan phone book. One number printed prominently at the beginning startled him. U.S. Secret Service 264–7204. It didn’t seem to Vladimir Zhukov to be very secret.

3 (#ulink_e54eab7e-8261-51af-b623-463002db339a)

THE Red House in Washington is a greyish building on 16th Street a few blocks—two-fifths of a mile maybe—from the White House. It is fairly ornate having been built for a good capitalist, Mrs George M. Pullman, whose husband designed and built Pullman cars for America’s railroads; and one of its first tenants was the Embassy of Czarist Russia. But the building, four storeys high including the ground floor, is a poor place compared with the great mansions of other countries ranged along Embassy Row, Massachusetts Avenue, where many expansive architectural styles vie with each other. (Here Britain seems to score with a statue of Sir Winston Churchill, who looks as if he might be hailing a bus, outside their elegant manor.) The Russians are perpetually aggrieved at the faded modesty of their home, but the Americans decline to do anything about it until they are given a better Embassy in Moscow. Likewise the Russians refuse the Americans more resplendent accommodation until they are given more prestigious premises in Washington; this childish intractability is often said to be symbolic of the two powers’ attitudes towards settling larger issues such as wars.

A small driveway leads up to the door, only twenty feet from the sidewalk. The windows have balconies; there is an undistinguished tree, pleading to be struck by lightning, in the small front garden, wire netting around the hedge, some interesting aerials on the roof arranged in the sort of art forms that normally outrage the Kremlin. Outside a West German Volkswagen or two, with diplomatic plates, which seems to indicate that ideological differences need not stand in the way of commercial economy.

Among the Embassy’s neighbours are the National Geographic Magazine and the University Club. The Washington Post lies around the corner.

A little way down 16th from the Embassy C.I.A. agent Joseph Costello sat at the wheel of his Thunderbird chewing on a dead cigar butt and privately expressing his opinion on what Mother Russia could do to herself. Snow mixed with freezing rain bounded along the street encasing the car in ice. And what’s more he wouldn’t put it past the stupid bastard to walk: he wouldn’t put it past a Russian to break the ice on the Potomac and go for a swim.

But I know my limitations, Joe Costello, Vietnam veteran and hero, acknowledged. Not for me the cocktail parties with The Beautiful People. I am strictly for surveillance and I am eternally grateful for the opportunities afforded me by my heroism (refusing to act stupid in front of my buddies) under enemy fire. Costello, hairy, squat and honest, further confided to himself: I wish to hell I’d made the grade as a professional football player for the Redskins. Still, I’m lucky to have a job like this, a cut above the F.B.I., two cuts above the precinct.

But surveillance on a shitty night like this! And for what? All he knew was that he had to follow the Russian and make sure that the meet with the State Department clerk took place as scheduled and that the Soviets didn’t try and hi-jack the clerk or anything. As far as he, Joe Costello was concerned, he would be very happy if they put a bullet in the State Department guy’s guts if he was a traitor. But who was he to express an opinion? Just surveillance.

Tardovsky, tall and thin and unmistakable, emerged from the embassy. Please get in your nice comfy little Volks, old buddy. But the Russian bent his thin neck into the rain and snow and walked quickly down 16th.

You sonofabitch! Costello got out of the car quietly and spat the cigar butt on to the sidewalk.

The meet was supposed to be in a bar on 14th, where pornography and bare flesh prospered alongside the palatial seats of national and world power. Very dark, probably, with a dirty movie grunting along in the background.

Tardovsky was heading in the right direction. But hadn’t anyone told him that Washington was the worst city in the States for getting mugged? And what the hell did he do if the Russian was jumped? On 14th anything could happen. On this sad street the orifice-filled bookshops and the girlie clip-joints were doing fair trade. A few bums, junkies and sharply-dressed blacks hung around the doorways. Jesus, Costello thought, right on the President’s doorstep.

Then he became aware that he was maybe not the only tail on Tardovsky. Behind the two of them he sensed another shadow. They were about to play games. But who the hell was the playmate?

Tardovsky entered the bar just off 14th and sat down at a table. On the screen a long way down the tunnel of the bar a couple stripped and simulated copulation; the girl showed her genitals with abandonment, her lover was more coy—maybe he was ashamed of them, Costello thought.

Tardovsky ordered a beer and took his hat off. Right, Costello thought—you should take off your hat in the presence of a lady. He sat way behind Tardovsky and glanced at his watch: five minutes till the meet. He ordered a Scotch from the girl in the crotch-high black skirt.

The second shadow sat down to the left of Costello, three tables away. Costello took a look at him. Very wet, like himself, very cold. Powerful looking, impossible to distinguish his features behind the turned-up collar of his bulky topcoat.

Why hadn’t they told him more? ‘Just keep your eye on them to make sure nothing goes wrong. Keep in touch.’ But they hadn’t mentioned a third party who could be Russian, American, British, Czech (they were pretty high in the espionage stakes these days). Three minutes to go.

Tardovsky, who looked bored with the repetitive sex looked at his watch and went to the toilet. The man in the bulky topcoat followed. Which means I have to follow too, Costello decided.

But the toilet wasn’t designed for espionage or the prevention thereof. With two big men bulging in the confined space behind him, Tardovsky didn’t bother to finish what he was doing at the stall. He zipped up, ducked between them with giraffe agility and was gone.

‘Shit,’ said Costello. He turned to follow.

‘Not so fast,’ said the other man, his face blond and fierce behind the collar.

‘Who the hell are you?’

‘Who the hell are you, buddy?’

‘It doesn’t matter now.’ Costello heaved towards the door.

‘Oh yes it does. Sure it does.’ The stranger chopped at Costello’s neck but hit his elbow on the wall. Costello got him in the stomach with two karate fingers; although the topcoat blunted the impact.

They fought savagely for a couple of minutes. But the toilet wasn’t designed for pugilism either. So they identified themselves and, while the faucet over the stall urinated noisily, silently contemplated their plight.

On the screen in the bar corner the young man indicated facially that orgasm was near while the girl sighed with what could have been ecstasy or frustration.

The personality of Wallace J. Walden was split down the middle on the subject of his capital city. He revelled in its dignified masonry, smooth lawns, stern statues, its libraries and museums and broad avenues, the stately homes of President and Government, the Washington Monument poised like a stone rocket set for launching. He loved to see tourists patrolling beneath Japanese cherry trees and expressing admiration at such a graceful seat of power. Sometimes he interrupted—‘I couldn’t help overhearing’—and put them straight on historic facts: Washington offered 500 dollars for a design for The Capitol and Dr William Thornton from Tortola in the West Indies won (‘Italian Renaissance, you understand’), the city was originally conceived by Pierre Charles l’Enfant, a protégé of Lafayette, as ‘a capital magnificent enough to grace a great nation’—‘And did you know that Washington who chose the site here in Maryland and Virginia was a surveyor himself? Few people seem to know that …’ Then he gave them the Visitors Information Service number (347–4554) before moving on to survey the Reflecting Pool, pillared palaces of bureaucracy, the spruce, beech and magnolia, with an awe and pride that had survived twenty-five years acquaintanceship.

The split occurred because Wallace J. Walden detested Washington’s principal industry—politics. Or, more particularly, he disliked intriguing politicians. Which was ironic because Walden’s own job was intrigue.

He admired ambition but abhorred its crude application; if there was one person he disliked more than a senator peddling a cause with votes in mind, rather than humanity, it was a senator’s wife pursuing the same objective over tea or Martinis. Jesus, he thought this glacial morning as he walked beside the whispering ice on the Tidal Basin, God save us from the women of Washington. (He was both a blasphemous and God-fearing man.) But, like it or not, Washington was a women’s city, every secretary trying to do a Jackie Kennedy. Only last night he had read in the Evening Star that the president of the Democratic Congressional Wives’ Forum was advising freshmen lawmakers to employ professional comedians to spike their speeches with gags. If they had their way, Walden ruminated without humour, Bob Hope would become president. Or Bill Cosby.

The wind blew eddies of snow across the ice separating Walden from Thomas Jefferson standing on pink Tennessee marble behind the white portico of his dome. ‘I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.’ So had Walden. He regretted that the means to his end involved intrigue, subterfuge and murder. But he had no doubts that the means justified the end.

He gulped down the iced air hungrily, felt the cold polish his cheeks. A lonely figure with heavy pipe gurgling, welted shoes marching firmly on the crusty ground, hat never too firm on the springs of his greying cropped hair.

Here every morning, after leaving his wife and enigmatic teenage children in Bethesda, Walden assembled his day. Today he was thankful for the ache in the air because, to an extent, it numbed his anger at the stupidity that had once again spoiled an inspired manoeuvre.

Tardovsky had been a prospective defector. One of the intellectuals who had smelled liberty, nibbled at abundant living, appreciated the ripe fruits of democracy. A patriot, sick of doctrinaire socialism, hesitating on the portals of freedom. Now he was lost for ever.

Walden had decided that Tardovsky was not the man to be courted with gifts, sleek-limbed girls on Delaware beaches, visits to perfect American homes with gentle and obvious persuasion over blueberry pie. So his honest, devious mind had considered other ploys. A doubter from the Soviet Embassy meeting a doubter from the State Department. Together they would renounce the duplicity of both great powers and seek refuge in some snowbound haven in Canada—where all the American trash found bolt-holes. But even if Tardovsky had ended up in Toronto or Montreal the defection would have occurred in the capital of the United States. A highly prestigious landmark on the road to The Final Solution: universal understanding of the Communist (and atheist) myth.

The F.B.I. had been pursuing the scheme energetically. A phoney State Department traitor had been established. Then apparently the C.I.A. had got wind of the stool-pigeon’s double-dealing and, never for one second allowing for the possibility of double, double-dealing, had arranged their own surveillance without confiding their plans.

Result: a fist fight in a men’s room in a dirty movie bar.

Thus, through the offices of bumbling incompetents, did tyranny survive. Thank God the K.G.B. was also served by incompetents who did everything by the book. If only I had the Mafia on my side …

Walden left the gaze of Jefferson, entered the spectrum of Lincoln and watched the children skating on the Reflecting Pool: it was their future he was fighting for. A jet rose heavily from the National Airport, keeping ominously low to restrict its noise, labouring over Lincoln’s Colorado marble shrine of freedom, justice, immortality, fraternity and charity. The qualities he had to preserve.

The grumbling line of traffic on Constitution Avenue opened at a red light and Walden crossed, heading for the State Department where he co-ordinated the various intelligence organizations behind a vague political title. That bum Costello! The heating in the lobby of this throbbing modern building, the laboratory of American influence, escalated his anger—a menacing, inexorable quantity not unlike the lurking hatreds of the intriguing Church dignitaries of history.

Walden summoned to his office that morning the heads of Security and Consular Affairs, Intelligence and Research, and Politico-Military Affairs. Also the deputy heads of the F.B.I. and the C.I.A.

‘Gentlemen,’ said Walden, handing around cigars, ‘a fiasco was perpetrated in our city last night. It is probably not necessary for me to say that, to an extent, we are all responsible.’

The ensuing silence did not imply unqualified agreement.

‘It is our joint responsibility, Goddammit!’ He picked up his pipe. ‘I’m sorry, gentlemen, but I’m disgusted at the way this operation has been handled.’

Jack Godwin from the C.I.A., a shifty egghead in Walden’s opinion, with an irritating habit of detaching morsels of tobacco from the tip of his tongue like a conjurer, ventured an opinion that, as the operation had been Walden’s brainchild, the failure was his responsibility. ‘Just like you would have accepted the plaudits if it’d been a success.’

Walden turned on him. ‘If you had kept me informed of your suspicions this foul-up would never have happened. Surely to Christ the C.I.A. is aware by now that its primary function is overseas intelligence?’

‘Sure we realize that,’ Godwin said. ‘But with practically every foreign country represented in Washington our job begins at home.’

‘You could co-ordinate with the Federal men. You could perhaps trust them to pass on to you any information they think you need.’

Godwin shrugged. ‘How do they know what we need?’

Arnold Hardin from the F.B.I. said, ‘It’s not outside our capabilities.’ A neat, late-middle-aged man, sarcastic and ingenious, as tidy as Godwin was unkempt.

The other three participants from the State Department kept their counsel. A secretary bearing coffee came into the aseptically chic office with its multiple telephones, maps of Moscow indicating the limits within which Americans could move, its photographs of the President, Vice-President and Secretary of State, its small battery of reference books which included The Bible.

The five of them stirred and sipped and waited.

Finally Gale Blair from Security and Consular Affairs said, ‘You shouldn’t take it so hard, Mr Walden. Think of all the successes.’ She was a smart, kindly woman.

They all thought hard.

Crawford from Politico-Military said, ‘The F.B.I. didn’t do too badly when they caught the Czechs trying to bug the office of Eastern European Affairs.’

‘Thank you,’ said Hardin, crossing elegant legs, flicking dust from a polished toecap. ‘But don’t forget to thank Frank Mrkua, the passport courier who made it possible by co-operating with us.’

‘And we should also be thankful to the F.B.I.,’ said Godwin, spilling coffee on his lived-in jacket, ‘for tapping the German Embassy and finding evidence of the Nazi-Soviet pact. In 1939,’ he added, timing it nicely.

Crawford, a diligent and enthusiastic man, said, ‘The F.B.I. also nailed Wennerstrom. They’ve got a whole bevy of defectors in the past couple of years. And what about this guy they caught making a drop under the railway bridge in Queens—he’s helped bust the Soviet network wide open. And the Soviets still think he’s working for them,’ Crawford supplied in case anyone present didn’t know.

‘Maybe he is,’ Godwin grunted.

Hardin sharpened his voice. ‘I sometimes wonder when they come to write the definitive history of the C.I.A. whether they’ll record the occasion when bugs were found inside the eagle the Soviets presented to the American Embassy in Moscow.’

Intelligence and Research spoke for the first time. ‘At least they were found.’ William Bruno, recognized as a shrewd nut; a reputation enhanced by his deep and golden silences. What went on in his Machiavellian mind during those contemplative periods? Bruno, thirty-fiveish with ambassadorial ambitions, was too shrewd a nut to tell anyone.

‘Jesus Christ …’ Godwin began.

Walden cut him short, ‘Let’s get back to the Goddam point before we start on Penkovsky or the U

.’ He stuck his pipe in his mouth. ‘We have to find a substitute for Tardovsky. He’s so scared now he won’t ask an American the way to the john. Any ideas?’ He turned to Hardin. ‘How are the infiltration stakes on 16th?’

Hardin made neat replies. ‘Pretty much the same as usual. A few bugs installed, most of them discovered. It’s tricky when all the manual work is done by Russians and even the cleaning’s done by the wives. But as you know or should know—‘he looked at Godwin—‘most of our approaches are made these days through other embassies. They work through the Cubans or Czechs, we use the Canadians and the British.’

Walden said, ‘But we could do with a good defector with all the inside dope. A name to make a splash like Dotsenko. Another Krotkov. And we need him in the United States, right here in Washington. We need something good and powerful to counter some of the lousy publicity our country has been getting lately. Don’t forget,’ he stared at them individually, ‘that it’s a war we’re fighting here. A war in which nearly the whole world’s involved—114 ambassadors, 2,500 diplomats. It’s a war more important even than World War II because the enemy is more powerful. It’s a war democracy has to win.’ His fingers reached out and touched The Bible.

Gale Blair said she understood perfectly and she was sure she spoke for everyone.

Walden swept on, massaging the greying stubble of his hair, pouring himself a cardboard cup of ice water. ‘The Communists have determined on an all-out bid to penetrate our intelligence agencies, our departments of State and Defence, our technological organizations, Congress itself—and I’m quoting from the forth-coming F.B.I. report Subversion from Abroad. It’s essential that we find a way of penetrating their headquarters in Washington—the Goddam embassy itself. It’s my job to co-ordinate this operation. So please,’ he said holding up his hands, ‘no more internecine feuding. For Christ’s sake let’s not have any more foul-ups like last night. That wasn’t just any old foul-up, gentlemen, that was a military defeat.’ He tossed back the water as if it were neat vodka. ‘Now, any ideas?’ He picked up a folder on his desk. ‘What about this new man, for instance. What’s his name?’ He opened the folder. ‘Vladimir Zhukov. What do we know about him?’

Hardin extinguished his cigar with a quick stab. ‘I guess that’s your department, Godwin. How much did your guys in Moscow, get on him?’

Godwin pulled a folder identical to the one on Walden’s desk from a bulging briefcase that looked as if it might contain sandwiches. ‘As a matter of fact,’ he said in his loose voice, ‘Comrade Zhukov is a possibility. No more than that. A faint, faint possibility.’

‘If he’s any kind of a possibility,’ Walden said, ‘then it’s up to us to make him into a probability.’

‘It’s very vague,’ Godwin mumbled.

Hardin said, ‘Don’t play games. If you’ve got something tell us what it is.’

‘It’s just that he writes poetry,’ Godwin said.

Godwin and Hardin stopped to talk in the hallway a few yards from Walden’s office, beside a sign bearing the words ‘Fall-out shelter in this corridor.’

‘Jesus,’ Godwin said. ‘What a pompous bastard he is.’

Hardin nodded impatiently. ‘Maybe. A ruthless one, too. But he comes up with some good ideas. Like the little scheme we goofed on last night.’

‘We?’

‘Oh, come on, Godwin. Forget your worldwide network just this once. You’re here in Washington—the capital of the little old United States. Sure, we goofed. And you know it. And Walden’s right—we’ve got to come up with something. So let’s you and I go and have coffee and work on it together.’

Godwin regarded him with massive, rumpled suspicion. ‘Okay, let’s go,’ He was still holding his thin dossier on Vladimir Zhukov.

Hardin opened his expensive black and silver attaché case. ‘By the way, I’ve got one of those, too.’ He took out another folder marked Vladimir Zhukov.

‘I know,’ Godwin said, ‘we circulated it to you.’

4 (#ulink_a76a56e8-00e1-5b4c-a676-02a7b326e5f8)

IN a students’ livingroom in Alma-Ata near the Kazakh State University a girl of eighteen with braided hair—now loosened—and wide eyes, just a little Mongolian, surrendered her virginity with enthusiasm.

She anticipated the textbook possibility of pain and absence of sensual feeling—‘the pleasure will come later, my dear’. But it was there the first time. Insistent pressure from his hard muscle, then oh! like a finger through parchment. And as he filled her the pleasure was instant, mounting, so that she clawed and bit and cried out, ‘I love you, Georgi. Oh, I love you.’

Not that Natasha Zhukova did love Georgi Makarov. But, she decided, I am certainly going to enjoy sex. With a few selected and privileged men who were clean and strong, handsome and intelligent; particularly intelligent. Like Georgi with his muscled belly, arrogant features—a little petulant sometimes—and his defiantly shaggy hair. A few such selected affairs before marriage and children and fidelity. I hope I’m not pregnant, she thought in alarm as his fluid escaped; but still, abortion was a mere formality.

‘I’m sorry, Natasha Zhukova,’ Georgi said, lying back and lighting a cigarette and not looking sorry at all.

‘Don’t be so bourgeois,’ she said irritably. Beneath the coarse blanket she explored the expended muscle, limp and sad. Such was the transience of masculinity: she would have liked to try it again.

Her thoughts wandered from the satisfied body beside her and wondered what sex would be like with the man she loved. If mere physical attraction could produce such earthy pleasure what delight lay ahead when love partnered consummation?

Another alarming thought: what if the man she loved and wished to marry despised her because she wasn’t a virgin? Wasn’t it Lenin himself who had said, ‘Does a normal man under normal circumstances, drink from a glass from which others have drunk?’ But, Natasha reassured herself, the alarm was academic: she would never love a man so narrow-minded. And it was certainly too late—by about five minutes—to worry.

The trouble with Soviet morals was that they were so confused. The Party denounced promiscuity but made abortion easier than a visit to the dentist, and divorce not much harder. And only fifty or so years ago, before the Glorious Revolution, a red cloth used to be flown over a bride’s house if she turned out to be a virgin, a white cloth if she didn’t. And when she was eight, only ten years ago, Natasha had read in Komsomolka about a girl, suspected of adultery with a married man, who had been solemnly advised to visit a clinic and get a certificate of virginity to display to her accusers.

Nowadays the Party was more concerned with general liberalism, with suppressing free expression. Natasha agreed with most Kremlin edicts. Its foreign policy (vaguely), its calls for collective effort to farm and weld, and research, its severity with drunks and those who were not sufficiently energetic in building socialism. Although she became quickly bored with the dreariness of their pronouncements.

What Natasha Zhukova could not countenance was the Kremlin’s treatment of intellectuals. Georgi Makarov was an intellectual. And a rebel, too. Every girl was attracted by a rebel. She slid her fingers through his thick brown hair, cut and combed with a suspicion of decadence.

‘You’re a strange girl, Natasha Zhukova,’ Georgi said. ‘The others have always cried.’

She knew he expected her to whine, ‘Others? Have there been others?’ Instead she said, ‘What’s there to cry about? It happens to most girls at some time or another.’ She also knew that he resented such practical reactions: they were the property of men.

‘Have you no romance in your soul?’

‘Of course—I am Russian. I have the soul of the taiga. And I am almost a Kazakh so I have the soul of the mountains. Or’—she turned on her side and grinned at him—‘a ripe Oporto apple waiting to be plucked.’

He shifted petulantly on the bed and lit another cigarette; his fingers were tobacco stained like those of all true revolutionaries. Except that his revolution was confined to a few secret essays, a signature on a petition seeking the release of Daniel and Sinyavsky, a few progressive jazz records. Outwardly it was all virile protest: inwardly bewilderment at the conflicting calls of patriotism and enlightenment.

Georgi said, ‘You sound like one of those American women with their demands for equality and free love. By love they mean sex. Conveyor belt sex. A woman should love from the heart.’

‘And not a man?’

The rebel shrugged.

‘It seems to me,’ Natasha suggested, ‘that the Americans and British are a long way behind us in many ways. We had the revolution of the sexes after the Great Revolution. “Down with bourgeois morality.” Wasn’t that the cry? Didn’t Alexandra Kollontaya preach that we women should free ourselves from the enslavement of love to one man? Don’t the older women still talk rapturously of those days when virginity was held up to mockery?’

‘Attitudes have changed again,’ Georgi told her. ‘Extremes always follow revolution. We have come to our senses again. Only the West pursues self-indulgence. Like the Romans—and the Romanovs—the people of the West are pursuing their own self-destruction.’ He sat up self-importantly.

Natasha stood up and walked to the window. Naked, enjoying his gaze. She looked across her father’s city, blurred with gentle snow that belied the dagger of winter. The City of Apples, karagachs, Lombardy poplars and birch trees, of wooden cathedrals with gold domes, of apartment blocks as standard as dogma, of ditches that sang with melting snow in the spring. And, of course, V. I. Lenin in the central square: a reminder, stern but gentle, of the dangers of too much frivolous appreciation.

And beyond Alma-Ata … the cuff of crumpled mountains, burnished wheat in the virgin lands, the gold of Ust-Kamenogorsk, the grapes of Chimkent, the sounds of stars above the launching pad at Baikonur. All helping to confuse allegiances, to the Republic of Kazakhstan (‘We occupy one-eighth of the Soviet Union and we are still regarded as peasants’), to Russia, to the Party, to young private doubt.

‘Georgi,’ she said, turning her back on him, proud of her smooth arching back, ‘why do we only read criticism about the West? Drugs, racism, exploitation.’ Pravda’s dictionary opened up in her mind. ‘There must be a lot of benefits from life in America and Britain.’ She knew she was being naïve.

‘Because impressionable young language students like you might get ideas.’

‘And you—don’t you get ideas? About music, about art, about self-expression? Isn’t that what your protest is all about? That writers here can’t write the truth as they can in the West?’

‘We do what we do for ourselves and for our country—even if our country doesn’t appreciate it. We don’t imitate what they do in the West.’

‘Why are copies of that magazine you read smuggled out to the West then?’

‘So that they don’t believe all they read about Russia.’ He wrapped a sheet around his waist, more shy after love than this formidable girl at the window, and stood beside her.

‘That’s what’s so sad,’ she said. She felt the warmth of his body behind her, smelled his sweat. ‘We don’t know the truth about America and I’m sure few Americans know the truth about us.’

About our gaiety most of all. Sad that the Americans never heard guitars strumming in the parks, smelled stews cooking in communal apartment blocks, ate cheese and sausage sandwiches or drank kvas at student parties, sang and cried (drunk even on mineral water), camped on river beaches, kissed on steamers. To Americans, Natasha suspected, Russia was a prison camp. And the smuggled literature of Georgi and his dangerous friends only encouraged that belief: it was ironic that all this free thought only made the picture of Russia blacker.

‘The West must know the truth,’ Georgi, who was studying political science, had explained.

‘But they already know everything bad about Russia.’

‘Only from their own propagandists.’

‘And what about our propagandists?’

‘Their work is so crude that no one in the West bothers to print it.’

‘So no one in America ever reads anything good about the country?’

‘I suppose not. And no one here ever reads anything good about America because their own propaganda is just as crude and no one bothers to reprint it here.’

‘It’s very bewildering,’ Natasha pronounced. ‘No one seems to make the effort to tell the truth. Either about themselves or the …’ she had hesitated then.

‘Or the enemy?’

‘I was searching for a more suitable word. But what chance have any of us if no one tries to explain?’

He had kissed her fondly, patronizingly. ‘I am glad you’re studying languages and not philosophy or logic or politics.’ Stick to your English and your sweet singing, his tone indicated.

But that was before they’d made love. Now the arrogance had receded, a dog’s bark lost in a blizzard. Paradoxically her loss had given her strength, and the spirit of Alexandra Kollontaya stirred within her. She giggled and led her confused lover back to the bed. The snow had stopped and the late sun cast dying light on the City of Apples. A snowplough prowled, a branch of silver birch, ice-sheathed and glittering with diamanté, scratched the window.

‘How much longer do we have?’ Natasha asked.

‘About half an hour. Yuri and Boris are very tactful.’

‘Since when?’ asked Natasha, thinking of Georgi’s two boisterous roommates.

‘They understand.’

‘You mean you made a pact with them to stay away while you deflowered a poor virgin?’

Georgi denied it so indignantly that Natasha knew he was lying. She was pleased with this new insight into the behaviour of men. She told him not to be so dramatic: someone had to deflower her.

‘Is that all it meant to you?’

Instinctively she knew that it was the woman who usually said that. ‘You were a wonderful lover,’ she said, taking up the script.

‘How would you know about that?’

‘Certainly I can’t make any comparisons. But you were wonderful.’ She combed his hair with her finger so that it fell in a thick fringe across his forehead. How many more scripts? She was not even sure what sort of man she would love. Big and strong and brainy was all very well, but she knew that such statutory requirements were discarded when love (not infatuation—she was prepared for that treacherous experience) finally surfaced.

She looked down at Georgi the rebel with affection. He is an attractive boy and at least we share bewilderment. And now, I think, a little honesty. She brushed a nipple across his face, felt his sharp ribs, hips, the awakening phallus—more arrogant now than its owner.

Then he made love to her again. Or was it the other way around? Anyway it was even better than the first time.

‘Georgi,’ she said, pulling on her grey skirt and black sweater, ‘don’t you think you should get your hair cut just a little?’

‘You sound like a wife already,’ he grumbled. He lingered on the bed, probably hoping to be caught in the middle of dressing—the conquering lover disturbed. How shallow, how presumptuous, how conceited. Perhaps she should say, ‘There he is, gentlemen, I have just seduced him. He’s all yours.’

She said, ‘I was only thinking of your own safety. The other night a Komsomol patrol grabbed a student off the street and forcibly cut his hair. They also read his notebooks.’

Georgi shrugged. ‘It’s a cheap way to get a haircut.’

‘But your notebooks, Georgi …’

‘I’m not stupid enough to write anything incriminating in them.’ He lit another cigarette. ‘Anyway they probably only did it for a little fun. It’s their job to stop hooliganism. There’s nothing wrong with that, is there?’

Natasha agreed that there wasn’t and began to braid her long shiny hair. She searched herself for the irreparable sense of loss that was supposed to accompany the loss of the maidenhead. She felt only satisfaction and a little soreness.

Georgi continued to lecture. ‘Although there are still changes to be made we’re lucky to be young now in 1968. No Stalin, no Beria, no 2 a.m. knocks on the door. And also we’re just young enough not to have been too badly affected by Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin. In 1956,’ he added in case she wasn’t too good on contemporary history. ‘Can you imagine what it must have meant to those kids? Why, once upon a time they used to sing a hymn to Stalin.’ He sung a few bars. ‘Leader, scattering darkness like sun, Conscience of the world, Luminary of the ages, Glory to him.’

They heard footsteps outside and a tentative knock. Georgi leapt out of bed, pulling on undershirt and pants. ‘Answer the door, Natasha. That’ll be Boris and Yuri.’

She smiled at him with maternal indulgence and went to the door.

The two plainclothes policemen pushed past her. ‘Georgi Makarov,’ one of them said, ‘please finish dressing and come with us.’

5 (#ulink_6d0029eb-93e8-54be-9485-dcad66fa2d4a)

IT was two weeks before Vladimir Zhukov staged his first unspectacular revolt. But the desire to buy was drooling in him. More than thirty years preparation for the impact of bloated capitalism and I am like a kid with five roubles to spend in a toy store.

Valentina observed his craving with contempt. ‘Don’t forget, Vladimir, that it has nothing to do with their system. It’s all a question of natural resources. And the fact that the settlers in America were the toughest and bravest people from Europe. And, of course, they avoided the devastation of the last war …’

‘I know,’ Vladimir said, ‘I attended that lecture, too.’

In any case her nagging was unnecessary. He despised the gluttony of living. But when in Rome … Would it do any harm to taste a little of the plunder? A single orgy couldn’t corrupt. A practical experience of decadent extravagance.

He began gently. At a drugstore on Dupont Circle called the People’s Drug—the name soothed his guilt. But even in this humble American mart the horn of plenty sounded loud in Zhukov’s ears. Stationery, perfume, magazines, paperbacks, ice-cream—pills and potions to ease the punishments of gluttony.

But it’s difficult to spend money after a lifetime of frugality, Zhukov discovered. He bought a comb and a tube of pink transparent toothpaste which Valentina might prefer to her tin of powder. So hard to spend and so easy to pay: no abacus, no hour-long queues, no trips from counter to cashier and back.

Shyly he ordered a cream soda from a day-dreaming Negro girl. Slyly added a dollop of ice-cream. Then furtively treated himself to a hotdog, squirting it thick with mustard, burying the punchy-skinned sausage in green relish; swallowing some paper napkin with his first bite.

The waitress said, ‘You go on eatin’ like that and you’re goin’ to be a plenty sick man.’

The schoolboy Zhukov apologized. ‘I didn’t have any breakfast.’ But his accent defeated and bored her. She moved indolently away, gawky limbed and graceful.

But why feel shame, Comrade Zhukov? Aren’t Muscovites the greatest eaters in the world? Stuffing themselves with creamy borsch, fat meats, black bread, cucumbers, potatoes, the gurievskaya kasha that Valentina cooked so well, the salted pig fat on thick bread that peasants still ate, the finest and creamiest ice-cream in the world. I shouldn’t feel shame at eating these synthetic snacks. He prodded the floating ice-cream with disdain. And a coffee, perhaps, to complete the culinary adventure. The girl who wore a blue-black wig slid him a cup and he experimented with the cushion of sugar and tiny pot of cream as if he were in a laboratory.

As he paid at the cash desk he belched.