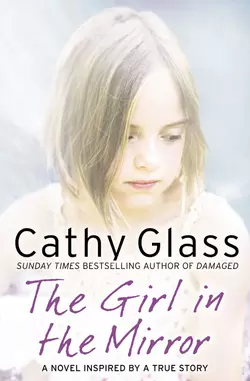

The Girl in the Mirror

Cathy Glass

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 962.99 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The Girl in the Mirror is a moving and gripping story of a young woman who tries to piece together her past and uncovers a dreadful family secret that has been buried and forgotten.When Mandy learns her much-loved Grandpa is dying, she is devasted and returns to the house where she spent so many wonderful summers as a child. But the childhood visits ended abruptly and those happy days are now long gone. Having lost touch with the rest of her family, Mandy returns as a virtual stranger to her aunt′s house to nurse her grandfather.Mandy hardly recognises the house that she loved so much as a child and it is almost as though her mind has blanked it out. But as certain memories come back to her, Mandy begins to piece together the events that brought a sudden end to her visits that fateful summer. What she discovers is so painful and shocking that she understands why it was buried and never spoken of by the family for all those years.