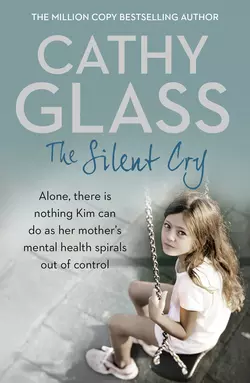

The Silent Cry: There is little Kim can do as her mother′s mental health spirals out of control

Cathy Glass

The heartbreaking true story of a young, troubled mother who needed help.The sixteenth fostering memoir by Cathy Glass.It is the first time Laura has been out since the birth of her baby when Cathy sees her in the school playground. A joyful occasion but Cathy has the feeling something is wrong. By the time she discovers what it is, it is too late. This is the true story of Laura whose life touches Cathy’s in a way she could never have foreseen. It is also the true stories of little Darrel, Samson and Hayley who she fosters when their parents need help. Some stories can have a happy ending and others cannot, but as a foster carer Cathy can only do her best.

(#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

Copyright (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the children.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2016

FIRST EDITION

© Cathy Glass 2016

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Cover image © Krasimira Petrova Shishkova/Trevillion Images (posed by model)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be

identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008153717

Ebook Edition © February 2016 ISBN: 9780008153724

Version: 2017-11-21

Contents

Cover (#ueb65aeb2-fc04-54f9-96e6-dff2181eaaba)

Title Page (#ulink_02e6e4c9-3253-550e-97e8-5597d86b1cba)

Copyright (#ulink_2aaa6815-3754-5738-89d8-004fd49ae477)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_95629c73-781d-5be1-b1f8-1d3774f1c093)

Prologue (#ulink_d9adfc6d-ab31-5de1-96a3-e98ee2ceeff3)

Chapter One: A Funny Turn (#ulink_2e9adc8c-6e35-5c5a-96b7-f70e2a881385)

Chapter Two: Very Concerned (#ulink_ad1a1540-e0fc-5e33-9bfb-2b227deee97d)

Chapter Three: Lullaby at Bedtime (#ulink_c7a9f76a-d123-5eea-954a-da5f5425a11c)

Chapter Four: Shelley (#ulink_0dae95ad-3416-5fce-8042-1f56bc60f7bb)

Chapter Five: A Very Strange Phone Call (#ulink_93c09200-1e32-5768-b9dc-07f36c5a3195)

Chapter Six: Useless (#ulink_a6a672b5-847d-5f18-8a14-2ba964761711)

Chapter Seven: Upset (#ulink_8d59a0bd-39a7-5da5-b6fc-be710639c28c)

Chapter Eight: A Playmate? (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Samson (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: The Devil’s Child (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Trying to Hurt Him (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: Very Serious (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: Worry (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: Gina (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen: Everley (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen: Home Again (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen: Progress (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen: Child Abuse (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen: Unwelcome News (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty: Waiting In (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One: Last Resort (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two: A Reprieve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three: Going Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Suggested topics for reading-group discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

Cathy Glass (#litres_trial_promo)

If you loved this book … (#litres_trial_promo)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

A big thank you to my family; my editors, Carolyn and Holly; my literary agent, Andrew; my UK publishers HarperCollins, and my overseas publishers who are now too numerous to list by name. Last, but definitely not least, a big thank you to my readers for your unfailing support and kind words.

Prologue (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

The room is dark, although it’s daylight outside. Strangely dark and eerily quiet. Not a sound when there should be noise. Crying and screaming, that’s what she was expecting to hear. And the room seems smaller now too, as though the walls are gradually closing in and crushing her, crushing her to death.

She sits huddled at one end of the sofa, too scared to look around. Scared of what she might see in this unnaturally dark and quiet room that is threatening to squeeze the air out of her and squash her to nothing. Scared, too, of what lies ahead if she stands and goes to the telephone to make that call, and tells them what she’s done. They will come and take her baby for sure if she tells them that she has given birth to the devil.

Chapter One

A Funny Turn (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

Everyone loves a newborn baby and wants a little look. Even those who protest that they are not ‘baby lovers’ can’t resist a peep at the miracle of a new life. I joined the other mothers grouped around the pram in the school playground as we waited with our children for the start of school.

‘Congratulations, he’s gorgeous,’ I said, adding my own best wishes to the many others.

‘Thank you,’ Laura (the new mum) said quietly, a little bemused by all the attention.

‘How old is he now?’ I asked.

‘Two weeks.’

‘Aah, he’s adorable.’

‘Make the most of every moment,’ another mother said. ‘They grow up far too quickly.’

My own daughter, Paula, aged thirteen months, was sitting in the stroller and wanted to have a look too, so I unclipped the safety harness and lifted her out so she could see into the pram.

‘Baby,’ she said cutely, pointing.

‘Yes, that’s baby Liam,’ I said.

‘Baby Liam,’ she repeated with a little chuckle.

‘You were that small once,’ I said, and she chuckled again.

‘He’s my baby brother,’ Kim, Laura’s daughter, said proudly.

‘I know. Aren’t you a lucky girl?’ I said to her, returning Paula to her stroller.

Kim nodded and touched her baby brother’s face protectively, then planted a delicate little kiss on his cheek.

The family had moved into the street where I lived about a year before. Laura and I had got to know each other a little from seeing each other on the way to and from school. My son Adrian, aged five, attended this school but was in a different year to Kim, who was seven. Living quite close to each other I kept meaning to invite Laura in for a coffee and develop our friendship, but I hadn’t found the opportunity, what with looking after my own family, fostering and studying for a degree part-time. I guessed Laura had been busy too, especially now she had a baby.

Amid all the oohings and aahings over little Liam the Klaxon sounded the start of school and parents began saying goodbye to their children.

‘Bye, love,’ I said to Adrian, giving him a kiss on the cheek. ‘Have a good day. Make sure you eat your lunch, and have a drink.’ He’d only been in school a year and I still fussed over him.

‘Bye, Mum. Bye, Paula,’ he said, and ran over to join his class who were lining up, ready to go in.

‘Bye, little Liam,’ Kim said, leaning into the pram again to give her brother one last kiss. She clearly didn’t want to leave him. ‘See you later. Be a good boy for Mummy.’ I smiled.

‘Cathy,’ Laura said suddenly, clutching my arm. ‘I feel a bit hot. I’m going to get a drink of water. Could you stay with the pram, please?’

She turned and walked quickly towards the water fountain situated in an alcove at the far end of the building. Kim looked at me anxiously.

‘Don’t worry, love. I’ll make sure your mum is all right. You go into school.’

She hesitated, but then ran over to join her class, who were going in. I could see Laura at the fountain, leaning forward and sipping the cool water. I thought I should go over in case she was feeling faint. She’d only given birth two weeks before and I could remember how I’d sometimes suddenly felt hot and dizzy in the first few weeks after having both of my children. Pushing Paula’s stroller with my right hand and Liam’s pram with my left, I steered them across the playground to the water fountain. ‘Are you OK?’ I asked Laura as we approached.

‘Oh, yes, thank you,’ she said, straightening and wiping her mouth on a tissue. ‘I came over a bit funny. I’m all right now.’

I thought she looked pale. ‘Why don’t you sit down for a while? The children are going in.’ There were a couple of benches in the playground that the children used at playtime.

‘No, I’m all right, honestly. I just felt a bit hot and panicky. I think it was all the attention, and it is warm today.’

‘Yes, it is warm for May,’ I agreed. ‘But make sure you don’t overdo it.’

She tucked the tissue into her pocket and shook her hair from her face. ‘My husband and mother-in-law said it was too soon for me to be out and about. I guess they were right. But I was getting cabin fever staying at home all the time. I needed a change of scenery.’ She put her hands onto the pram handle ready for the off.

‘Are you going straight home?’ I asked. ‘I’ll walk with you.’

‘Yes, but there’s no need. I’ll be fine.’

‘I’d like to,’ I said. ‘I walk by your house on the way to mine.’

‘All right. Thanks.’ She flicked her hair from her face again and we began across the playground to the main gate. Laura was a tall, attractive woman, whom I guessed to be in her mid-thirties, and she was very slim despite recently giving birth. She had naturally wavy, shoulder-length brown hair, which was swept away from her forehead.

‘Is Liam sleeping and feeding well?’ I asked, making conversation as we walked.

‘Baby,’ Paula repeated, pointing to his pram travelling along beside her.

‘Yes, that’s right,’ I said to her. ‘Baby Liam.’

‘I’m up every three hours at night feeding him,’ Laura said. ‘But you expect that with a newborn, don’t you?’

I nodded. ‘It’s very tiring. I remember craving sleep in the first few months. If someone had offered me a night out at a top-class restaurant or seven hours unbroken sleep, I would have gone for the latter without a doubt.’

‘Agreed,’ Laura said with a small smile.

We were silent for a few moments as we concentrated on crossing the road, and then we turned the corner and began up our street. ‘How do you like living here?’ I asked, resuming conversation.

‘Fine. It’s nearer Andy’s – my husband’s – job, and his family. My mother-in-law only lives five streets away.’

‘Is that the lady I’ve seen in the playground, collecting Kim from school?’ I asked out of interest.

‘Yes. Geraldine. She’s very helpful. I don’t know what I’d do without her.’

‘It’s good to have help,’ I said. ‘My parents help me out when they can, but they live an hour’s drive away, and my husband’s family are even further away.’

‘Yes,’ Laura said, looking thoughtful. ‘My mother lives over a hundred miles away. You foster, don’t you?’

‘I do, although I’m taking a few months off at present to finish my degree. After our last foster child left my husband accepted a contract to work abroad for three months, so it seemed a good opportunity to study. The social services know I’m available for an emergency or for respite care, but I’m hoping I won’t be disturbed too often.’

‘What’s respite?’ Laura asked, interested.

‘It’s when a foster carer looks after a child for a short period to give the parents or another foster carer a break. It might just be for a weekend or a week or two, but then the child returns home or to their permanent carer.’

‘I see. It’s good of you to foster.’

‘Not really. I enjoy it. But I must admit I’ve been struggling recently to study and foster, with Paula being so little. Hopefully I’ll now have the chance to complete my dissertation.’

‘What are you studying?’

‘Education and psychology.’

She nodded. We’d now arrived outside her house, number 53, and Laura pushed open the gate. ‘Well, it’s been nice talking to you. Cathy, isn’t it?’

‘Yes – sorry, I should have said.’

‘Thanks again for helping me out in the playground. I hope I haven’t kept you.’

‘Not at all. If ever you want me to collect Kim from school or take her, do let me know. I’m there every day with Adrian.’

‘Thanks, that’s kind of you, but Geraldine, my mother-in-law, always does it if I can’t.’

‘OK. But if she can’t at any time you know where I am. And perhaps you’d like to pop in for a coffee one day when you’re free.’

She looked slightly surprised. ‘Oh, I see. That’s nice, but I expect you’re very busy.’

‘Never too busy for a coffee and a chat,’ I said with a smile. ‘I’ll give you my telephone number.’ I began delving into my bag for a pen and paper.

‘Can you give it to me another time?’ Laura said, appearing rather anxious. She began up her garden path, clearly eager to be away. ‘Sorry, but I’m dying to go to the bathroom!’ she called.

‘Yes, of course. I’ll see you later in the playground. I can give it to you then.’

‘Geraldine will probably be there,’ she returned, with her back to me, and quickly unlocking the door. ‘Push it through my letterbox.’

‘OK. Bye then.’

‘Bye!’ she called, and going in closed the front door.

‘Baby Liam,’ Paula said, pointing to the house.

‘Yes, that’s where he lives,’ I said.

‘Out!’ Paula now demanded, raising her arms to be lifted out of the stroller.

‘Yes, you can walk, but remember you always hold my hand.’

I undid the safety harness, helped her out and took her little hand in mine. ‘We always hold hands by the road,’ I reminded her. I didn’t use walking reins but insisted she held my hand.

‘Baby Liam,’ Paula said again, looking at his house.

‘Yes, that’s right.’ I glanced over. A woman, whom I now knew to be Laura’s mother-in-law, Geraldine, was looking out of the downstairs window. I smiled and gave a little wave, but she couldn’t have seen me for she turned and disappeared into the room.

‘Home,’ Paula said.

‘Yes, we’re going home now.’

We continued haltingly up the street with Paula stopping every few steps to examine something that caught her interest, including most garden gates, walls, fences, lampposts, fallen leaves, every tree in the street and most of the paving slabs. But I knew that the exercise would tire her out and that once home, after she’d had a drink and a snack, she’d have at least an hour’s sleep, which would give me the chance to continue researching and writing my dissertation: ‘The psychological impact being in care has on a child and how it affects their educational outcome.’

That afternoon, before I set off to collect Adrian from school, I wrote my telephone number on a piece of paper and tucked it into my pocket ready to give to Laura. She wasn’t in the playground and for a while it appeared that no one had come to collect Kim, for I couldn’t see Geraldine either. The Klaxon sounded for the end of school and the children began to file out, and then Geraldine rushed into the playground at the last minute and went over to Kim. Adrian arrived at my side very excited because his class was going on an outing. He handed me a printed sheet with the details of the outing and a consent form, and I carefully tucked it into my bag. I looked around for Geraldine, but she’d already gone. We joined the other parents and children filing out of the main gate and then crossed the road. As we turned the corner into our street I could see Kim and her grandmother a little way ahead. Kim turned and gave a small wave. We waved back. I was half-expecting Geraldine to turn and acknowledge us, or maybe even wait for us to catch up and fall into conversation, but she didn’t. She kept on walking until they arrived at number 53, where she opened the garden gate and began up the path. As we drew level she was opening the front door.

‘Excuse me!’ I called. She turned. ‘Could you give this to Laura, please?’ I held out the piece of paper. ‘It’s my telephone number. I said I’d let her have it. Is she all right now?’

Geraldine nodded, straight-faced, and tapped Kim on the shoulder as a signal for her to collect the paper.

Kim ran down the path and smiled at me as she took the paper. ‘Thank you,’ she said politely.

‘Say hi to your mum,’ I said.

‘I will.’

With another smile she ran back up the path to her grandmother, who’d now opened the front door and was waiting just inside, ready to close it. I smiled at her but she didn’t return the gesture, and as soon as Kim was inside she closed the door. With her short grey hair and unsmiling features Geraldine came across as stern. I was slightly surprised by her coldness, and it crossed my mind that she’d very likely seen me that morning through the front-room window and, for whatever reason, had chosen to ignore me.

Chapter Two

Very Concerned (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

I saw Geraldine in the playground every day for the rest of that week – in the morning when she took Kim to school, and in the afternoon when she collected her – but she didn’t acknowledge me or make any attempt to start a conversation. Neither did she have anything to do with any of the other parents waiting in the playground, which was unusual. It was a relatively small school, and friendly, so that eventually most people started chatting to someone as they waited for their children. But Geraldine didn’t; she hurried into the playground at the last moment and out again, aloof and stern-looking. By Friday, when Laura still hadn’t reappeared, I began to wonder if she was ill. She’d had a funny turn earlier in the week, on her first outing with Liam – perhaps she’d been sickening for something and was really poorly. Although Geraldine apparently didn’t want anything to do with me, Laura hadn’t been so hostile, and given that we lived in the same street and our children attended the same school I felt it would be neighbourly of me to ask how she was. If you are feeling unwell and someone asks after you it can be a real pick-me-up. So on Friday afternoon when Geraldine collected Kim from school I intercepted her as she hurried out of the playground.

‘I was wondering how Laura was,’ I said. ‘I’m Cathy. I live in the same street.’

‘Yes, I know who you are,’ she said stiffly. ‘Laura is fine, thank you. Why do you ask?’ Which seemed an odd question.

‘When I last saw Laura she wasn’t feeling so good. She came over a bit hot and wobbly. I wondered if she was all right now.’

‘Oh, that. It was nothing,’ Geraldine said dismissively. ‘It was far too soon for her to be going out and she realizes that now.’

I gave a small nod. ‘As long as she’s not ill.’

‘No, of course not,’ she said bluntly.

‘Good. Well, if she ever fancies a change of scenery and a coffee, she knows where I live.’

‘Oh, she won’t be up to that for a long while,’ Geraldine said tartly. ‘I’ve told her she’s not to go out for at least another four weeks, possibly longer. That’s the advice we had after giving birth.’ Taking Kim by the arm, she headed off.

Not go out for another four weeks! You could have knocked me down with a feather. Wherever had she got that from? It was nearly three weeks since Laura had given birth and as far as I knew there was no medical advice that said a new mother had to wait seven weeks before going out, unless Geraldine was confusing it with postpartum sex, but even then seven weeks was excessive if the birth had been normal. More likely, I thought, Geraldine was suffering from empty-nest syndrome and she liked being the centre of the family and having Laura rely on her. It would make her feel needed, and if that suited Laura, fine. It was none of my business. I’d been reassured that Laura wasn’t ill, and I had my family to look after and work to do.

It was the weekend and the weather was glorious, so Adrian, Paula and I spent most of Saturday in the garden, where the children played while I read and then did some gardening. On Sunday my parents came for the day and after lunch we were in the garden again. In the evening after they’d gone, my husband, John, telephoned from America where he was working. He’d got into the habit of telephoning on a Sunday evening when it was lunchtime where he was. We all took turns to speak to him and tell him our news. Even little Paula ‘spoke’ to him, although she was bemused by the workings of the telephone and kept examining the handset, trying to work out where the voice was coming from, rather than holding it to her ear.

On Monday the school week began again, and as the weather was fine we walked to and from school. I only used my car for school if it was raining hard or if I had to go somewhere straight after school. Geraldine continued to take Kim to school and collect her, and continued to ignore me and all the other parents. Perhaps she was just shy, I thought, although she had a standoffish, austere look about her. Each time I passed Laura’s house, number 53, which was four times a day (on the way to and from school), I glanced over. But there was never any sign of Laura or baby Liam, so I assumed Laura was making the most of having Geraldine in charge and was relaxing indoors or in the back garden. Sometimes Paula pointed to the house and, remembering that Liam lived there, said, ‘Baby.’ If she was out of her stroller and walking, she tried the gate – and most of the others in the street!

On Thursday afternoon, once we’d returned home from school, we hadn’t been in long when the telephone rang. It was a social worker asking if I could do some respite and look after a little boy, Darrel, aged three, for that night and all day Friday. His mother, Shelley, a young, single parent, had to go into hospital as a day patient and the person who was supposed to have been looking after Darrel had let her down at the last minute. She had no one else she could ask at such short notice, and I said I’d be happy to help and look after Darrel.

‘Shelley’s a young mum but she’s a good one,’ the social worker said. ‘She’ll bring Darrel to you at about six o’clock this evening. She said she’d bring everything he needs, but she’s fretting that she’s run out of meatless sausages. She’s a vegetarian and she’s bringing up Darrel the same. Apparently he loves meatless sausages for lunch, but she hasn’t got time to go into town and buy more. I’ve told her you’ll be able to cook him something else vegetarian.’

‘Yes, of course I will, but tell her I’ll see if I can get some of the sausages. If she’s not bringing Darrel until six, I’ve got time to pop down to our local supermarket. I’m sure I’ve seen some there.’

‘Oh, you are good. I’ll tell her. It’s the first time Darrel has been away from her overnight and she’s getting herself into a bit of a state. It’s understandable.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed.

‘She has to be at the hospital at eight o’clock tomorrow morning and she should be discharged later that afternoon. If she does have to stay overnight or doesn’t feel up to collecting Darrel on Friday evening can he stay with you for a second night?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Thank you. I’ll phone Shelley now and reassure her, and give her your contact details.’

‘I’ll see her about six then.’ We said goodbye and I hung up. I hadn’t been told what was wrong with Shelley and I didn’t need to know. But I could appreciate why she was anxious at being separated from her son and was fretting because he would miss his favourite food. I’d seen the meatless sausages in the freezer cabinet at the supermarket a few weeks before when I’d been looking for something else. I just hoped they’d still have some in stock. But it’s strange the way things work out sometimes, as if it’s meant to be, for had I not offered to go to the supermarket I would probably have remained ignorant of what was really going on in Laura’s house.

‘Sorry,’ I said to Adrian and Paula. ‘We’ve got to pop down to the shop.’

Adrian pulled a face. ‘We’ve only just got in and I wanted to play in the garden.’

‘You can play as soon as we return,’ I said. ‘We won’t be long. We’re looking after a little boy tonight and he likes a special type of sausage. I want to see if I can buy some.’

Adrian was growing up with fostering, as was Paula, so it didn’t surprise him that a child could suddenly appear and join our family. It was when they left that he didn’t like it. Neither did I, but as a foster carer you have to learn to accept that the children leave you, and you take comfort from knowing you’ve done your best to help the child and their family, and then be ready for the next child.

‘Can I have an ice cream from the shop then?’ Adrian asked cannily.

Usually the answer would have been, ‘No, not before your dinner,’ but given that he was having to come out again and go shopping rather than playing in the garden, I thought a little reward was in order.

‘Yes, a small one that won’t spoil your dinner,’ I said.

‘Yippee, ice cream!’ Adrian said.

‘Ice cream,’ Paula repeated.

‘Yes, you can have one too.’

As Adrian put on his trainers I fitted Paula’s shoes and then lifted her into the stroller, which I kept in the hall.

The local supermarket was at the bottom of my street, to the right, on the same road as the school. While it wasn’t suitable for a big shop it was very useful for topping up, and I often popped in if we were running short on essentials. If they didn’t have the sausages in stock I would tell Shelley I’d tried and then ask her what else Darrel liked to eat. I was sure I’d be able to find something else he liked. Although he was only staying with me for a day or so, it was important the experience was a good one for him and his mother, and that included meeting his needs and accommodating his likes and dislikes where possible. I would also ask Shelley about Darrel’s routine, and I’d keep to it as much as possible to minimize the disruption to him. Even so, despite everything I was going to do, he was still likely to be upset – a three-year-old left with strangers. Had this not been an emergency respite placement he could have come for a visit beforehand to meet us, so it wouldn’t be so strange for him.

As we walked down the street Adrian asked, ‘Will Darrel go to my school?’

‘No, he’s not old enough for school yet,’ I said.

‘Oh, yes, of course,’ Adrian said, with an embarrassed grin. ‘I knew that really. I am a muppet.’

‘Muppet,’ Paula repeated.

‘You’re a muppet,’ Adrian said, teasing his sister and ruffling her hair.

‘Muppet,’ she said again, giggling.

‘You’re a muppet,’ Adrian said again. And so we continued down the street with the word ‘muppet’ bouncing good-humouredly back and forth between the two of them.

‘So how do we cross the road safely?’ I asked Adrian as we arrived at the pavement edge.

‘Think, stop, look and listen, and when it’s all clear walk, don’t run, across the road,’ he said, paraphrasing the safety code that they’d been taught at school.

‘Good boy.’

We waited for the cars to pass and then crossed the road and went into the supermarket. I took a shopping basket and we went straight to the freezer cabinet. To my relief they had three packets of meatless sausages; I took one and placed it in the basket. Adrian then spent some time selecting ice creams for him and Paula and put those in the basket too. Paula reached out and began whining, wanting her ice cream straight away. ‘I have to pay for it first and take off the wrapper,’ I said.

We headed for the checkout. As we turned the corner of the aisle we saw Kim with a shopping basket on her arm, looking at a display of biscuits. ‘Hello, love,’ I said. ‘Are you helping your mum?’

‘Yes,’ she said, a little self-consciously. I glanced around for Laura but couldn’t see her. ‘Where is she?’ I asked her. ‘I’ll say hello.’

‘She’s at home,’ Kim said.

‘Oh, OK. Tell her I said hi, please.’

Kim smiled and gave a small nod.

I wasn’t going in search of her grandmother, whom I assumed was in one of the other aisles, to say hello, so we continued to the checkout. There was a woman in front of us and as we waited another joined the small queue behind us. Then, as we stepped forward for our turn, I saw Kim join the queue. The cashier rang up our items and placed them in a carrier bag, which I hung on the stroller. I paid and before we left I looked again at Kim and smiled – she was still waiting in the queue, without her grandmother.

Outside the shop I parked the stroller out of the way of the main door and gave Adrian his ice cream, and then removed the wrapper from Paula’s. I glanced through the glass shopfront and saw that Kim was now at the till. ‘Surely Kim isn’t here alone?’ I said out loud, voicing my concerns.

Adrian shrugged, more interested in his ice cream.

I threw the wrappers in the bin but didn’t immediately start for home.

‘Can we go now?’ Adrian asked impatiently. ‘I want to play in the garden.’

‘Yes, in a minute.’

I watched as Kim packed and paid for her shopping and then came out. ‘Are you here alone?’ I asked her.

She gave a small, furtive nod, almost as if she’d been caught doing something she shouldn’t.

‘We can walk back together,’ I suggested.

She gave another small nod and we crossed the pavement and waited on the kerb. I was surprised and concerned that Kim was by herself. She was only seven, and while there is no law that states a child of seven shouldn’t go out alone I thought it was far too young. She wasn’t in sight of her house, she was by herself and she’d had to cross quite a busy road. A foster child certainly wouldn’t have been allowed to make this journey alone at her age, and neither would I have allowed my own children to do so.

‘Is your mother all right?’ I asked Kim as we began up our street. I wondered if there had been an emergency, which had necessitated Kim having to buy some items.

‘Yes, thank you,’ she said politely.

‘Where’s your gran?’ I asked, trying not to sound as though I was questioning her.

‘At her house,’ Kim replied.

‘And you’ve been doing some shopping for your mother?’ She nodded. ‘Do you often do the shopping?’ I asked after a moment, for she appeared quite confident in her role.

‘Yes, sometimes, since Mum had Liam.’

‘Does your gran not do the shopping then?’

‘Sometimes, but Mum doesn’t always like the things Gran buys.’

So why not ask her to buy the things she does like? I thought but didn’t say.

‘And your mum didn’t want to walk down with you?’ I asked as we walked.

‘She’s got a bad headache. She’s in bed, and Dad won’t be home until later.’

‘Oh dear.’ I could see Kim looking enviously at Adrian’s and Paula’s ice creams and I wished I’d thought to buy her one. ‘So who’s looking after Liam?’ I asked.

‘He’s in the pram, asleep. I wanted to bring him with me, but Mum wouldn’t let me. If she’s not up later I can make him a bottle,’ Kim added proudly. ‘I know what to do.’

I smiled and hid my concerns. This wasn’t making sense. If Geraldine liked to help, why wasn’t she helping the family now when they needed her? Laura was in bed, unwell, and Kim’s father wasn’t home. Why not phone Geraldine and ask for help? She only lived five streets away. We were drawing close to Laura’s house now.

‘What time does your dad get in from work?’ I asked her. ‘Do you know?’

‘I think it’s usually about seven-thirty or eight,’ Kim said.

That was three hours away. ‘Does he know your mum is unwell and you had to go to the shop?’ We’d arrived at her garden gate.

‘No,’ Kim said, and opened the gate. If I hadn’t been expecting Shelley and Darrel, I would have gone in and asked Laura if there was anything I could do.

Kim paused on the other side of the gate as she looped the carrier bag over her arm and took a front-door key from her purse.

‘Kim, will you please tell your mother I said hello and to phone me if there is anything I can do? She has my telephone number.’

‘Yes. Thank you,’ Kim said sweetly, and then hesitated. With a slightly guilty look she said, ‘You won’t tell Dad or Gran you saw me, will you?’

‘No, but is there a reason?’

‘They wouldn’t like it,’ Kim said. With a little embarrassed smile she turned and continued up the path to her front door.

I watched her open the door and go in. There was no sign of Laura. The door closed and we continued on our way home.

‘Why is Kim doing the shopping?’ Adrian asked, having heard some of the conversation.

‘Her mother isn’t feeling well.’

‘Would I have to do the shopping if you weren’t well?’ he said through a mouthful of ice cream.

‘No. You’re too young.’

‘So who would do the shopping while Dad’s away if you were ill?’

‘I’d ask Sue [our neighbour], or another friend, or Nana and Grandpa. But don’t you worry, I’m not going to be ill.’ I knew Adrian was anxious about his father working away, and he occasionally asked who would do the jobs his dad usually did, like cutting the grass, or about other ‘what if’ scenarios, and I always reassured him.

I paused to wipe ice cream from Paula’s mouth and hands, as it was melting faster than she could eat it, and then we continued up the street towards home. Perhaps it was from years of fostering that I instinctively sensed when a child might be hiding something, and I felt that now with Kim. What she might be hiding I didn’t know, but I had a nagging doubt that something wasn’t right in her house. I decided that the following week, at the first opportunity, I would make a neighbourly call and knock on Laura’s door – unless, of course, she was in the playground on Monday, which I doubted.

Chapter Three

Lullaby at Bedtime (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

We’d just finished dinner that evening when the doorbell rang, and Adrian and Paula came with me to answer the door. Although it was still light outside I checked the security spyhole before opening it.

‘I’m Shelley and this is Darrel,’ the young woman said, with a nervous smile.

‘Yes, I’ve been expecting you, love. Come in.’

‘This is the lady I told you about,’ Shelley said, bending down to Darrel. He was standing beside her, holding her hand, and now buried his face against her leg, reluctant to come in.

‘He’s bound to be a bit shy to begin with,’ I said.

‘I know. I understand how he feels,’ Shelley said, clearly anxious herself. ‘Look, Darrel, Cathy has children you can play with.’

‘This is Adrian and this is Paula,’ I said.

But Darrel kept his face pressed against his mother’s leg as she gently eased him over the doorstep and into the hall. I closed the front door. Adrian, two years older than Darrel and more confident on home territory, went up to him and touched his arm. ‘Would you like to come and play with some of my toys?’ he asked kindly.

‘That’s nice of you,’ Shelley said, but Darrel didn’t look up or release his grip on his mother.

Then Paula decided that she, too, was shy and buried her face against my leg.

‘Do you want to leave your bags there?’ I said to Shelley, pointing to a space in the hall. ‘I’ll sort them out later.’

She was carrying a large holdall on each shoulder and, unhooking them, set them on the floor. She was also carrying a cool bag. ‘Could you put these things in the fridge, please?’ she said, handing me the cool bag. ‘There’s a pot containing his porridge for breakfast. I made it the way he likes it, with milk, before we came, so you just have to heat it up.’

‘OK, that’s fine, thank you.’

‘And there’s some yoghurt in there as well, and diced fruit in little pots. He has them for pudding and snacks. I’ve also put in a pint of full-cream milk. He prefers that to the semi-skimmed. I give him a drink before he goes to bed. I forgot to tell the social worker that and I didn’t know if you had full-cream milk here.’

‘I’ve got most things,’ I said, trying to reassure her. ‘But it’s nice for Darrel to have what you’ve brought.’

‘Oh, the sausages!’ Shelley exclaimed.

‘Yes, I got some. Don’t worry.’

‘Thank you so much. I am grateful.’ Then, bending down to Darrel again, she said, ‘Cathy has got your favourite sausages. Isn’t that nice?’

But Darrel kept his face pressed against his mother, and Shelley appeared equally nervous and anxious.

‘Try not to worry. He’ll be fine soon,’ I said. ‘Come and have a seat in the living room, while I put these things in the fridge.’

Shelley picked him up and held him tightly to her. I thought he was probably sensing her anxiety as much as he was nervous and shy himself. I showed them into the living room. Adrian went in, too, while Paula, slightly unsettled, came with me into the kitchen. At her age it was more difficult for her to understand fostering.

‘Baby?’ she asked as I set the cool bag on the work surface and unzipped the lid.

‘No, Darrel is older than you. He’s three. He’s sleeping here for one night. You can play with him.’

I began putting the contents of the cool bag into the fridge as Paula watched. Shelley seemed to have thought of everything, and I recognized the love, care, concern and anxiety that had gone into making up all these little pots so that Darrel had everything he was used to at home. Each pot was labelled with his name, what the pot contained and when he ate the food – so, for example: Darrel’s porridge, breakfast, around 8 a.m., and Darrel’s apple and orange mid-morning snack, around 11 a.m. Once I’d emptied the cool bag I returned to the living room with Paula and placed the bag near Shelley. ‘All done,’ I said.

‘Thank you so much,’ she said gratefully. Darrel was sitting on her lap, with his face buried in her sweater. ‘I’ve written down his routine,’ she said, passing me a sheet of paper that she’d taken from her bag.

‘Thanks. That will be useful.’ I sat on the sofa and Paula sat beside me. Adrian was on the floor, playing with the toys and glancing at Darrel in the hope that he would join in.

‘I’m sure he’ll play with you soon,’ I said. Then to Shelley: ‘Would you and Darrel like a drink?’

‘No, thank you, we had one before we left. He had warm milk, and he has one before he goes to bed too. I put the milk in the bag.’

‘Yes, I saw it, thanks. Although I’ve got plenty of milk here. Has he had his dinner?’

‘Yes, and I gave him a bath this morning so there is no need for him to have one this evening. I thought it would be better for him if I did it rather than him having to have a bath in a strange house. No offence, but you know what I mean.’

I smiled. ‘Of course. Don’t worry. I’ll keep to your routine. I’ll show you both around the house before you leave, so it won’t be so strange.’

‘Thank you.’

I guessed Shelley was in her early twenties, so she could only have been seventeen or eighteen when she’d had Darrel, but she obviously thought the world of him, and, as the social worker had said, she was a good mother. She was slim, average height, with fair, shoulder-length hair and was dressed fashionably in jeans and layered tops. She had a sweet, round face but was clearly on edge – she kept frowning and chewing her bottom lip. I knew Darrel would pick up on this. Paula, at my side, was now chancing a look at Darrel as if she might be brave enough to go over to him soon. Shelley saw this. ‘Come and say hello to Darrel,’ she said. ‘He’s just a bit shy, like me.’

But Paula shook her head. ‘In a few minutes,’ I said.

‘I think I’ve packed everything Darrel needs,’ Shelley said. ‘His plate, bowl, mug and cutlery are in the blue bag in the hall. I’ve put in some of his favourite toys and Spot the dog. He’s the soft toy Darrel takes to bed. Darrel is toilet trained, but he still has a nappy at night. I’ve put some nappies in the black bag, but he only needs one. I didn’t have room to bring his step stool, but he needs that to reach the toilet.’

‘Don’t worry. I have a couple of those,’ I said. ‘They are already in place in the bathroom and toilet.’

‘Thanks. I’ve put baby wipes in the blue bag too. His clothes and night things are in the black bag, but I couldn’t fit in his changing mat.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I said again. ‘I have one of those too. In fact, I have most things children need.’

‘Oh, yes, of course, you would have,’ Shelley said with a small, embarrassed laugh. ‘You have children and you foster. Silly me.’

She was lovely but so anxious. ‘I promise I’ll take good care of Darrel and keep him safe,’ I said. ‘He’ll be fine. How did you get here with all those bags and Darrel?’

‘On the bus,’ she replied.

‘I wish I’d known. I could have come and collected you in the car.’

‘That’s kind, but we’re pretty self-sufficient. I like it that way. You can’t be let down then.’ She gave another nervous little laugh and I wondered what had happened in her past to make her feel that way.

Toscha, our lovable and docile cat, sauntered into the room and went over to Adrian.

‘Oh, you’ve got a cat!’ Shelley exclaimed. For a moment I thought she was going to tell me that Darrel was allergic to cat fur and it could trigger an asthma attack, which was true for some children. Had this not been an emergency placement I would have known more about Darrel, including facts like this. Thankfully Shelley now said excitedly, ‘Look at Cathy’s cat, Darrel. You like cats. Are you going to stroke her?’ Then to me: ‘Is she friendly?’

‘Yes, she’s very friendly. She’s called Toscha.’

Toscha was the prompt Darrel needed to relinquish his grip on his mother’s jersey. He turned and looked at the cat and then left her lap and joined Adrian on the floor beside Toscha. Paula then forgot her shyness and slid from the sofa to join them too.

‘Toscha likes being stroked,’ I said. Which was just as well, as three little hands now stroked her fur and petted her while she purred contentedly. Now Darrel was less anxious I could see Shelley start to relax too. With a small sigh she sat back in her chair.

‘I know I shouldn’t worry so much,’ she said. ‘But coming here brought back so many memories.’

I smiled, puzzled. ‘Oh yes? What sort of memories?’

‘Going into a foster carer’s home for the first time. I was in care for most of my life and I had so many moves. I hated having to move. New people and new routines. It was so scary. I felt scared most of my early life. I thought I’d got over all of that, but bringing Darrel here today brought it back.’ Which I thought explained at lot of Shelley’s apprehension and anxiety. ‘I’d rather die than let my little boy lead the life I had,’ she added.

‘He won’t,’ I said. ‘You’ll make sure of it. You’re doing a great job. Your social worker told me what a fantastic mum you are. I’m sorry your experiences in care weren’t good. It was wrong you had to keep moving, very wrong, but try not to worry about Darrel. He’ll be fine here with me and you’ll see him again tomorrow.’ My heart went out to her. Whatever had the poor child been through?

‘Thank you,’ she said quietly. ‘I worry about him so much. He’s all the family I have. I nearly wasn’t allowed to keep him when he was a baby. I had to prove to the social services that I could look after him.’

‘And you’ve done that,’ I said firmly. ‘Admirably.’ But I could see she was worried, and I understood why she had overcompensated. ‘Do the social services still have any involvement with you and Darrel?’ I asked, which again would have been something I’d known if the placement had been planned.

‘Not since Darrel was eighteen months old,’ Shelley said. ‘That’s when their supervision order stopped. It was a great relief. I was going to cancel my hospital appointment tomorrow when my friend let me down and said she couldn’t look after Darrel. But I knew I’d have to wait ages for another appointment and my teeth really hurt. I’ve got two impacted wisdom teeth and they’re taking them out under general anaesthetic tomorrow. I was really nervous when I phoned the social services to ask for help. I hung up twice before I spoke to anyone. Then I got through to my old social worker and told her what had happened. She was lovely and asked how Darrel and I were. She said she’d see what she could do to arrange something for Darrel so I didn’t have to cancel my appointment.’

I nodded sympathetically, and not for the first time since I’d started fostering I realized just how alone in the world some people are. ‘So who is collecting you from hospital tomorrow?’ I asked.

‘No one. I’ll get a cab here.’

‘I can come and collect you,’ I offered.

‘That’s nice of you, but I’ll be fine, and I don’t know what time I’ll be discharged.’

‘You could phone me when you know and I’d come straight over. The hospital isn’t far.’

She gave a small shrug. ‘Thanks. I’ll see how it goes.’ And I knew that given her comment about being self-sufficient she’d have to be feeling very poorly before she took up my offer of help.

Toscha had sauntered off and the children were now playing with the toys I’d set out. It was after six-thirty and at some point Shelley would have to say goodbye to Darrel and leave, which would be difficult for them both. The sooner we got it over with the better, and then I could settle Darrel before he went to bed.

‘I’ll show you around the house before you go,’ I said to Shelley.

Her forehead creased and she looked very anxious again. ‘I was thinking, if you don’t mind, is it possible for me to stay and put Darrel to bed? Once he’s asleep I’d go, and he wouldn’t be upset.’

Each fostering situation is different, and foster carers have to be adaptable to accommodate the needs of the child (or children) they are looking after, and also often the parents too. There was no reason why she couldn’t stay.

‘Yes, that’s fine with me,’ I said. ‘But we will need to explain to Darrel what is happening. Otherwise he’ll wake up in the morning expecting to find you here, and be upset when you’re not.’

‘Darrel, love,’ Shelley said, leaving her chair and going over to kneel on the floor beside him, ‘I’ve got something to tell you.’

He stopped playing and looked at her, wide-eyed with expectation and concern.

‘It’s nothing for you to worry about,’ she reassured him. ‘But you remember I explained how you would be sleeping here for one night while I went into hospital?’

Darrel gave a small nod.

‘Well, I am not going to leave you until after you are asleep. Then, in the morning when you wake up, Cathy will be here to look after you until I come back. I’ll be back as soon as I can tomorrow. All right, pet?’

‘Yes, Mummy,’ he said quietly.

‘Good boy.’ She kissed his cheek.

I thought Shelley had phrased it well, and at three years of age Darrel would have some understanding of ‘tomorrow’.

‘Shall we have a look around the house now?’ I suggested. ‘You can see where you will be sleeping,’ I said to Darrel.

‘Yes, please,’ Shelley said enthusiastically, standing. Darrel stood, too, and held her hand. He looked at Adrian and Paula, now his friends.

‘Yes, they will come too,’ I said. They usually liked to join in the tour of the house I gave each child when they first arrived, although obviously there was no need, as they lived here. ‘This is the living room,’ I began. ‘And through here is the kitchen and our dining table where we eat.’

As we went into the kitchen Darrel exclaimed, ‘There’s the cat’s food!’ and pointed to Toscha’s feeding bowl.

‘That’s right,’ I said, pleased he was thawing out a little. ‘It’s empty now because Toscha has had her dinner.’

‘I’ve had my dinner,’ Darrel said.

‘I know. Your mummy told me. What did you have? Can you remember?’

‘Stew,’ he said. ‘With dumplings.’

‘Very nice. Did you eat it all up?’

‘Yes.’

‘He’s a good eater,’ Shelley said. ‘He’s likes my bean stew. I learned to make it from a recipe book. I put in lots of vegetables and he eats it all.’

‘Very good,’ I said, impressed, and thinking I should make stew and dumplings more often.

We went down the hall and into the front room. Given that Darrel was only young and here for one night, I didn’t go into detail about what we used the rooms for; I was just showing him around so he was familiar with the layout of the house and would hopefully feel more at home.

‘We’ll bring the bags up later,’ I said as I led the way upstairs. We went round the landing to Darrel’s room.

‘It’s not like my room at home,’ he said, slightly disappointed as we went in.

I smiled. ‘I’m sure your bedroom at home is fantastic, and it’ll have all your things in it, but this will be fine for tonight.’

‘Yes, thank you, Cathy,’ Shelley said, frowning at Darrel. ‘It’s very nice.’

I then briefly showed them the other rooms upstairs, including the toilet and bathroom where the step stools were already in place. I made a point of showing Darrel where I slept so that if he woke in the night he knew where to find me. It helped to reassure the child (and their parents), although in truth I was a light sleeper and always heard a child if they were out of bed or called out in the night.

‘Thank you very much, Cathy,’ Shelley said, and we began downstairs.

We returned to the living room and the children played with the toys again. Shelley sat on the floor with them and joined in, childlike and enthusiastic in her play. She carefully arranged the toy cars and play-people in the garage and sat the attendant behind the cash desk. I thought that, like many children from neglected and abusive backgrounds, she’d probably missed out on her childhood and had grown up fast to survive. After a while she left the children to finish their game and joined me on the sofa. I took the opportunity to explain to her that I would have to take Darrel with me to school in the morning when I took Adrian. I said that if he couldn’t manage the walk there and back I had a double stroller I could use.

‘He’ll be fine walking,’ Shelley said. ‘It’s not far, and he walks everywhere with me. I don’t have a car and I sold his stroller six months ago as I needed the money.’ I appreciated it must be difficult for her financially, bringing up a child alone.

It was nearly seven o’clock and I said I usually took Paula up for her bath and bed about this time.

‘It’s nearly Darrel’s bedtime too,’ Shelley said. ‘Can I give him his drink of warm milk now?’

‘Yes, of course. I’ll show you where everything is in the kitchen.’

Leaving the children playing I took Shelley into the kitchen, showed her around and then left her to warm Darrel’s milk, while I took Paula upstairs to get ready for bed.

‘Baby bed?’ Paula asked.

‘Darrel will be going to bed soon,’ I said, guessing that was what she meant. My reply seemed to satisfy her, for she chuckled.

I gave Paula a quick bath, put her in a clean nappy and then, after lots of hugs and kisses, tucked her into her cot bed. ‘Night, love,’ I said, kissing her soft, warm cheek one last time. ‘Sleep tight and see you in the morning.’

Paula grinned, showing her relatively new front teeth, and I kissed her some more. I said ‘Night-night’ again and finally came out, leaving her bedroom door slightly open so I could hear her if she didn’t settle or woke in the night, although she usually slept through now.

Downstairs Darrel had had his milk and Shelley was in the kitchen, washing up his mug while Darrel played with Adrian in the living room. Shelley looked quite at home in the kitchen and I asked her if she’d like a cup of tea, but she said she’d like to get Darrel to bed first. We went into the living room where she told Darrel it was time for bed. ‘Say goodnight to Adrian,’ she said.

‘Goodnight,’ Darrel said politely, and kissed Adrian’s cheek. Adrian looked slightly embarrassed at having a boy kiss him, but of course Darrel was only three.

‘I’m sorry,’ Shelley said, seeing Adrian’s discomfort. ‘He always kisses me when we say goodnight.’

‘It’s fine,’ I said. ‘As Mrs Clause says in Santa Clause: The Movie, “If you give extra kisses, you get bigger hugs!”’

‘That’s lovely,’ Shelley said, clasping her hands together in delight. ‘I’ll have to remember that – “If you give extra kisses, you get bigger hugs!”’

Adrian grinned; he loved that Christmas movie and the saying, as I did.

Shelley and I carried the holdalls upstairs and into Darrel’s room, with Darrel following. Having checked she had everything she needed, I left Shelley to get Darrel ready for bed and went downstairs. I’d got into the routine of putting Paula to bed first and then spending some time with Adrian. He usually read his school book, then we’d play a game or just chat, and then I’d read him a bedtime story and take him up to bed. It was our time together, set aside from the hustle and bustle of him having a younger sister and fostering. Now, as I sat on the sofa with my arm around him, we could hear Shelley moving around upstairs while she saw to Darrel.

‘It’s strange having another mummy in the house,’ Adrian said.

‘Yes, it is,’ I agreed. ‘But it’s rather nice.’ It was touching and reassuring to hear another mother patiently and lovingly tending to the needs of her child.

Once I’d finished reading Adrian his bedtime story, he put the book back on the shelf and then went over to say goodnight to Toscha as he did every night. She was curled on her favourite chair and he gently kissed the top of her furry head once and then twice. ‘Remember, Toscha,’ he said. ‘“If you give extra kisses, you get bigger hugs!”’

‘That’s right,’ I said. ‘Although I’d be very surprised if she got up and hugged you.’ Adrian laughed loudly.

‘Mum, you are silly sometimes.’

We went upstairs and while Adrian went to the toilet I checked on Paula. She was fast asleep, flat on her back, with her arms and legs spread out like a little snow angel. I kissed her forehead and crept out, again leaving her door slightly open. Shelley was in Darrel’s room now and through their open door I could hear her telling him that she would only go once he was asleep, and then she’d come back for him as soon as possible the next day. There was anxiety in her voice again, and I hoped it wouldn’t unsettle Darrel, for it could take hours before he went to sleep.

I ran Adrian’s bath and waited while he washed – even at his age I didn’t leave him unattended in the bath for long. I also washed his back, which he often forgot about. Once he was out, dried and dressed in his pyjamas, I went with him to his room. Following our usual routine, he switched on his lamp and I switched off the main light, then I sat on his bed while he snuggled down and settled ready for sleep. He often remembered something he had to tell me at this time that couldn’t wait until the morning. Sometimes it was a worry he’d been harbouring during the day, but more often it was just a general chat – a young, active boy delaying the time when he had to go to sleep. But tonight we heard Shelley talking quietly to Darrel in the room next door.

‘Will Darrel still be here when I come home from school tomorrow?’ Adrian asked.

‘I don’t think so. His mother is hoping to collect him in the early afternoon.’

‘He’s nice, isn’t he?’ Adrian said.

‘Yes, he’s a lovely little boy, just like you.’

Adrian smiled and I stroked his forehead. ‘Time for sleep,’ I said.

Then we both stopped and looked at each other in the half-light as the most beautiful, angelic voice floated in from Darrel’s room. Shelley was singing him a lullaby and her soft, gentle voice caressed the air, pitch perfect and as tender and innocent as a newborn baby – it sent shivers down my spine. First Brahms’s ‘Lullaby’ and then ‘All Through the Night’:

‘Sleep, my child, and peace attend thee,

All through the night,

Guardian angels God will send thee,

All through the night …’

By the time she’d finished my eyes had filled and I swallowed the lump in my throat. It was the most beautiful, soulful singing I’d ever heard, and I felt enriched for having been part of it.

Chapter Four

Shelley (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

‘You’ve got a lovely voice,’ I said to Shelley when she finally came downstairs from settling Darrel for the night.

‘Thank you. I wanted to become a professional singer, but that won’t happen now.’

I was in the living room with the curtains closed against the night sky, reading the sheet of paper Shelley had given to me on Darrel’s routine. ‘Would you like that cup of tea now?’ I asked her.

‘Yes, please. Shall I make it?’

‘No, you sit down,’ I said, standing. ‘You’ve had a busy day. Milk and sugar?’

‘Just milk, please.’

‘Would you like something to eat now too?’ I asked. ‘It’s a while since you had dinner.’

‘A biscuit would be nice, thank you,’ Shelley said. ‘I usually have one with a cup of tea when I’ve finished putting Darrel to bed.’

I went through to the kitchen, smiling at the thought of Shelley’s little evening ritual, not dissimilar to my own, of putting the children to bed first and then sitting down and relaxing with a cup of tea and a biscuit. I guessed parents everywhere probably did something similar.

I made the tea, set the cups and a plate of biscuits on a tray and carried it through to the living room. ‘Help yourself to biscuits,’ I said, putting the tray on the occasional table and passing her a cup of tea.

‘Thank you. You’ve got a nice home,’ she said sweetly. ‘It’s so welcoming and friendly.’

‘That’s a lovely compliment,’ I said, pleased.

‘Do you find it hard with your husband working away?’ Shelley asked, taking a couple of biscuits.

‘I did to begin with,’ I said. ‘But we’re in a routine now. And my parents will always help out if necessary.’

‘I wish I had parents,’ she said.

‘Where are they?’ I asked. ‘Do you know?’ It was clear that Shelley wanted to talk, so I felt it was all right to ask this.

‘My mum’s dead, and I never knew my dad. I think he’s dead too,’ she said without self-pity.

‘I am sorry.’

She gave a small shrug. ‘It was a long time ago. It happened when I was a child. They were both heavy drug users. It was the drugs that killed my mum and I think my dad too. I remember my mum from when I was little, but not my dad. I never saw him. I have a photo of my mum at home. I keep it by my bed. But even back then you can see she was wasted from the drugs. When the kids at secondary school started boasting that they’d been trying drugs I used to think: you wouldn’t if you saw what they did. My mum was only twenty-six when she died, but she was all wrinkled and wizened, and stick thin.’

‘I am sorry,’ I said again. ‘You’ve had a lot to cope with in your life. And it must be difficult bringing up a child completely alone. Although you are doing a good job,’ I added.

Shelley gave a small nod and sipped her tea. ‘I was a week off my eighteenth birthday when I had Darrel,’ she said, setting the cup on the saucer. ‘All my plans had to be put on hold. I had great plans. I wanted to be something. Go to college and study music and try to become a professional singer. I thought I’d get a good job, buy a house and a car, and go on holidays like other people do. But that’s all gone now. I know other young single mums and, although we all love our children, if we’re honest we’d do things differently if we had our time over again – get a job and training first, meet someone, set up home and then have a family. You can’t do that if you have a child.’

‘It is difficult,’ I agreed. ‘You’re not in touch with any of your foster carers?’

‘No. I was moved so often I can’t even remember most of their names. Some of them were nice, others weren’t. The only one I really felt was like a mother to me was Carol. I was with her from when I was fourteen to when I was seventeen. She was so nice. She helped me through a really bad time. But when I was seventeen the social worker said I had to go and live in a semi-independence unit ready for when I left care. Carol tried to stay in touch – she phoned and put cards through my door – but I never got back to her.’

‘That’s a pity. Why not?’

Shelley shrugged. ‘Not sure. But I was dating then and I sort of put my trust in him.’

‘Have you thought about trying to contact Carol now?’ I asked. ‘I’m sure she’d be pleased to hear from you.’

‘It’s been over three years,’ Shelley said.

‘Even so, I still think she’d be pleased if you did get in touch. I know I am when a child I’ve fostered leaves and we lose contact, and then they suddenly phone or send a card or arrive at my door. Foster carers never forget the children they look after, but once the child has left the social services don’t tell us how you are doing.’

‘I didn’t realize that,’ Shelley said, slightly surprised. ‘I’ll think about it.’ She took another biscuit.

‘Are you sure I can’t make you something proper to eat?’ I asked.

‘No, really, I’m fine. I must go soon.’ But she didn’t make any move to go and I was happy for her to sit and talk. ‘When I found out I was pregnant,’ she continued, ‘Darrel’s father had already left me. I told the social worker getting pregnant was an accident, but it wasn’t a complete accident. I mean, I didn’t plan on getting pregnant – I wanted to go to college – but neither did I take any precautions. I was pretty messed up at the time, and I sort of thought that having a child would give me the family I’d never had. I wanted to be loved and needed.’

‘We all want that,’ I said. ‘It’s such a pity you weren’t found a forever family. I don’t understand why the social services didn’t look for an adoptive family for you, with both your parents dead.’

‘They did,’ Shelley said in the same matter-of-fact way. ‘I was adopted. But it didn’t work out.’

‘Didn’t work out?’ I asked, dismayed. ‘Adoption is supposed to be for life. In law, an adopted child is the same as a birth child.’

‘I know. They even changed my surname to theirs. I was with them for two years, from when I was nine. But then the woman got pregnant. They thought they couldn’t have kids and when the baby was born they were all over it and I was pushed out. That’s what it felt like. So I started playing up and being really naughty. I remember doing it because I felt like no one loved me, so they put me back into care.’

‘That’s awful,’ I said. ‘I am so sorry to hear that.’ It was such a sad story, but Shelley didn’t appear bitter.

‘That’s life,’ she said with a dismissive shrug. Draining the last of her tea, she returned the cup and saucer to the tray. ‘I’d better be going. Thanks for listening. I hope I haven’t kept you.’

‘Of course not. I’ve enjoyed having your company. And please don’t worry about Darrel. I’ll take good care of him. I hope the operation goes well.’ The clock on the mantelpiece showed it was nearly ten o’clock. ‘Shelley, I don’t really want you going home on the bus alone at this time. Can I call a cab? I’ll pay for it.’

‘That’s kind of you. I’m not usually out this late,’ she said with a small laugh. ‘I’m usually at home with Darrel. But is it safe for a woman to be alone in a cab? I mean, you read bad stuff in the papers.’

‘It’s a local firm I know well,’ I said. ‘They have at least one lady cab driver. Shall I see if she’s free?’

‘Yes, please. I’ll pop up to the loo while you phone them.’

I called the cab firm and the controller said they had a lady driver working that night, so I booked the cab. He said she would be with us in about fifteen minutes. Shelley had been right to be concerned, a young woman alone in a cab, but I was confident she’d be safe using this firm or I wouldn’t have suggested it. I heard her footsteps on the landing, but before she came downstairs she went into Darrel’s room. A few moments later she returned to the living room. ‘He’s fast asleep,’ she said, joining me on the sofa. ‘He should sleep through, but he’ll wake early with a sopping wet nappy. I’m trying to get him dry at night, but it’s difficult.’

‘You could try giving him his last drink in the evening earlier,’ I suggested. ‘Perhaps with his dinner, or just after. That’s what I did with Adrian and the children I’ve fostered who were still in nappies at night. After all, what goes in must come out!’

She smiled. ‘Yes, very true. I’ll give it a try.’

I told her the cab was on its way and, taking out my purse, I gave her a twenty-pound note to pay the fare.

‘It won’t be that much,’ she said. ‘I’ll give you change.’

‘No. It’s OK. Buy yourself something.’

‘Thank you. That is kind.’

We continued chatting, mainly about Darrel and being a parent, until the doorbell rang. I went with her to the front door and opened it. The lady driver said she’d wait in her cab.

‘Good luck for tomorrow,’ I said to Shelley. ‘And phone me if you change your mind about a lift back from the hospital.’

‘All right. Thanks for everything,’ she said, and gave me a big hug. ‘How different my life would have been if I’d been fostered by you,’ she added reflectively.

I felt my eyes fill. ‘Take care, love, and see you tomorrow.’

I waited with the door open until she was safely in the cab, and then I closed and locked it for the night. Shelley’s unsettled past was sadly not a one-off. Too many children are bounced around the care system (for a number of reasons) and never have a chance to put down roots and have a family of their own. These young people often struggle in adult life, and feeling unloved can lead to drink and drugs or abusive relationships. Since I started writing my fostering memoirs I’ve been heartbroken by some of the emails I’ve received from young men and women with experiences similar to Shelley’s. Far more needs to be done to keep children in the same foster family or adoptive home so that they grow up and meet the challenges of adulthood with the confidence and self-esteem that comes from being loved and wanted.

Before I went to bed I checked all three children were asleep, leaving their bedroom doors ajar so I would hear them if they called out. I never sleep well when I have a new child in the house. I’m half listening out in case they wake and are upset. As it happened, Darrel slept through, but I woke with a start at six o’clock when I heard him cry, ‘Mummy!’

I was immediately out of bed and going round the landing in my dressing gown. The poor little chap was sitting up in bed, his round face sad and scared. ‘Where’s Mummy?’ he asked.

‘She’s gone to the hospital to have her tooth made better,’ I said, sitting on the edge of the bed. ‘I’m Cathy. Do you remember coming here yesterday? You’re staying with me while Mummy is at the hospital, then she’ll come and collect you.’

But he wasn’t reassured. His face crumbled and his tears fell. ‘I want my mummy.’

‘Oh, love, come here.’ I put my arm around him and held him close. It was only natural for him to be upset, waking in a strange bed and being separated from his mother for the first time.

‘It’s all right,’ I soothed, stroking his head. ‘I’ll look after you until Mummy comes back.’

‘I want my mummy,’ he sobbed. ‘Where’s my mummy?’

I felt so sorry for him. ‘She’s not here, love. She’s at the hospital. You’ll see her later.’

But he wouldn’t be consoled. ‘Mummy! Mummy!’ he called out with rising desperation. I knew it was only a matter of time before he woke Adrian and Paula.

Sure enough, a moment later Adrian’s feet pitter-pattered round the landing and he came into Darrel’s room in his pyjamas, looking very worried.

‘It’s OK,’ I reassured him and Darrel. ‘Darrel will be fine soon.’

‘Don’t be upset,’ Adrian said, coming over to Darrel and gently rubbing his arm. ‘We’ll look after you. You can play with my best toys in my bedroom if you like.’

‘Wow. Did you hear that, Darrel?’ I said to him. ‘Adrian says you can play with his best toys.’ He kept them in his bedroom out of harm’s way, as Paula at thirteen months was still rather clumsy.

The offer to play with an older boy’s best toys was too good to refuse, and far more comforting than my well-meant words of reassurance. Darrel’s tears stopped and he climbed out of bed. ‘I have to take my nappy off first,’ he said to Adrian.

I knew from Shelley’s notes that she used baby wipes to clean Darrel in the morning, and then he went to the toilet. So once he was clean and dry, he stayed in his pyjamas and went into Adrian’s room where Adrian had already set out some toys for them both to play with. With the boys occupied and Paula still asleep, I took the opportunity to shower and dress. By the time I’d finished Paula was awake and jumping up and down in her cot wanting to be ‘Out! Out!’ so I got her dressed. I took her with me into Adrian’s room, thanked him for looking after Darrel and left him to dress while I helped Darrel in his room. Aged three, Darrel could mostly dress himself but needed some help, especially with his socks, which are difficult for young children – he kept getting them on with the heel on top.

By the time we arrived downstairs for breakfast Adrian was Darrel’s best friend and he wouldn’t let him out of his sight. I had to push his chair right up close to Adrian’s at the table so they were touching, and he chatted away to Adrian. I warmed up the porridge Shelley had made for him and poured it into a bowl. Before Darrel began eating he asked Adrian if he’d like some. ‘Mummy won’t mind,’ he said cutely.

‘That’s OK, you have it,’ Adrian said. ‘I’ve got wheat flakes.’ In truth, Adrian had gone off porridge and didn’t eat it at that point.

Paula was sitting on her booster seat at the table, opposite Darrel, and was far more interested in watching him than she was in feeding herself. He was a new face at the table and she didn’t understand why he was there. I was sitting beside her and kept filling her spoon from her bowl of hot oat cereal and reminding her to eat. Darrel finished his porridge and I gave him the fruit his mother had prepared. He gave us a grape each, which we thanked him for and ate. ‘Very nice,’ I said.

Mindful of the time ticking by, I shepherded everyone upstairs and into the bathroom to brush their teeth and wash their faces. It was quite a logistical exercise getting three small children ready to leave the house on time, but eventually they were all in the hall with their jackets done up and their shoes on. Paula wanted to walk, but there wasn’t time, so I told her she could walk on the way back from school and lifted her into the stroller and fastened her safety harness before she had a chance to protest. Outside she wanted to hold Darrel’s hand as he walked beside her stroller and he was happy to do so, finding the novelty of a little one quite amusing. The boys talked to each other as we walked and Darrel told Adrian he would be starting school in September when he was four.

We arrived in the school playground with a few minutes to spare and I glanced around for any sign of Kim, but she wasn’t there. The Klaxon sounded for the start of school and Adrian began saying goodbye to us all. Although I’d already explained to Darrel that Adrian would have to go to school, I don’t think he understood the implications, for he suddenly looked very sad. ‘Don’t leave me,’ he said. I thought he was going to cry.

Adrian looked at me anxiously. ‘You go in,’ I said. ‘Don’t worry. Darrel will be fine.’ It was possible they might see each other at the end of school, but I couldn’t promise, as that would depend on what time Shelley was discharged from hospital and came to collect Darrel.

Saying goodbye, Adrian ran over to line up with his class and I turned to Darrel. ‘I could do with your help,’ I said to distract him. ‘Paula’s going to walk back and she obviously likes holding your hand. When I let her out of the stroller could you hold one of her hands, please, and I’ll hold the other? She doesn’t understand about road safety yet, so it’s important she holds our hands.’

Darrel rose to the occasion. ‘I’m good at helping,’ he said proudly, looking less sad. ‘I help my mummy.’

‘Excellent.’

I undid Paula’s harness and helped her out of the stroller. As I did I saw Geraldine rush into the playground with Kim. Neither of them looked at me as they were concentrating on getting Kim into school on time. I still intended to call on Laura the following week if she didn’t appear in the playground. With Darrel on one side of Paula and me on the other, we made our way out of the main gate and began our walk home. It was a slow walk – very slow – but it didn’t matter, as it kept Darrel occupied and distracted him from worrying about his mother. He found Paula’s habit of stopping every few steps to examine something in detail very funny. ‘What’s she looking at now?’ he said, laughing. ‘It’s a twig, Paula!’ Or, ‘It’s another stone. You are funny.’ It was nice to see him happy, and Paula was enjoying his company, although I don’t think she understood why her behaviour was amusing. At one point Geraldine overtook us on the opposite side of the street, although she didn’t look in our direction.

Paula paused as usual outside number 53 and rattled the garden gate. ‘Baby,’ she said, recognizing the house.

‘Yes, baby Liam lives there,’ I said. I glanced at the windows, but there was no sign of anyone.

She took another couple of steps up the street and then stopped to examine a weed that was sprouting between the paving slabs.

‘It’s a weed,’ Darrel said. ‘There are lots of them!’

And so we continued our meandering journey home.

Chapter Five

A Very Strange Phone Call (#ua795b969-a622-5dea-b063-7dfce1291e87)

Once home, I kept Darrel and Paula entertained with various games and activities, and then at eleven o’clock I gave both children a drink and a snack, before putting Paula in her cot for a little nap. While she slept I read to Darrel from books he chose from our bookshelves, and then we had a few rounds of the card game Snap, which he was learning to play. He asked about his mummy a couple of times and I reassured him that she was being well looked after and he’d see her before too long, so he wasn’t upset. I knew from Shelley’s notes that he had his lunch at about 12.30 p.m., so once Paula was awake I got her up and cooked vegetarian sausages, mash and peas for us all. I’d just set the food on the table when the doorbell rang.

‘Mummy?’ Darrel asked.

‘I think it’s a bit early yet,’ I said. ‘Stay here and I’ll check.’

Leaving the children at the table, I went down the hall to answer the door. To my surprise it was Shelley, looking very pale, with one side of her face swollen and a bloody tissue pressed to her lips.

‘Oh, love,’ I said, concerned and drawing her in. ‘Whyever didn’t you phone me to collect you? I hope you haven’t come on the bus.’

‘I got a cab,’ she mumbled, stepping in and barely able to speak. ‘I used the rest of the money you gave me.’ It obviously hurt her when she spoke.

‘Have you taken something for the pain?’ I asked.

She nodded. ‘Paracetamol.’

‘Mummy!’ Darrel cried, having heard his mother’s voice. He left the table and ran into the hall but stopped dead when he saw her swollen face.

‘It’s all right,’ I reassured him. ‘Mummy’s mouth is sore, but she’ll be better soon. I think she needs looking after.’ I took her hand and led her down the hall and into the living room. As we passed Darrel she managed a wonky smile, but he looked very concerned. ‘Mummy’s going to have a quiet sit down while you have your lunch,’ I said, settling her on the sofa.

‘Thank you,’ she said, sitting back with a small sigh.

‘Can I get you anything?’ I asked.

‘A glass of water, please.’ She winced as she spoke and put her hand to her face.

‘You sit there and I’ll fetch it,’ I said. Then to Darrel, ‘Come with me. We’ll leave Mummy to have a rest.’

He hesitated.

‘Go on, love,’ Shelley said. ‘Good boy.’

He slipped his hand into mine and I took him to the dining table, where Paula was still seated and making a good attempt to feed herself using her toddler fork and spoon. ‘Good girl,’ I said, returning the peas to her plate.

Darrel picked up his knife and fork and began eating, while I went into the kitchen and poured Shelley a glass of water. I added a straw to make drinking it a little easier, then took the glass through to the living room.

‘Thank you,’ she said gratefully, and gingerly took a few sips before handing it back to me. She sighed and rested her head back on the sofa.

‘Would you like to go upstairs for a lie down?’ I suggested.

‘I’ll just sit here for a bit if that’s all right.’

‘Yes, of course.’ I set her glass of water on the coffee table within her reach and also a box of tissues. ‘Do you want anything else?’ I asked. She shook her head and her eyelids began to close. ‘Call me if you need anything,’ I said. She nodded and I came out closing the door behind me so the children and I wouldn’t disturb her. I thought a sleep would do her good; having an anaesthetic can leave you feeling very tired.

‘Mummy is having a rest,’ I said to Darrel as I returned to the table. ‘She’ll be all right soon, so you have your lunch and when she wakes we’ll tell her what a good boy you’ve been.’