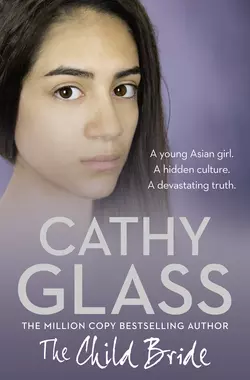

The Child Bride

Cathy Glass

Cathy Glass, international bestselling author, tells the shocking story of Zeena, a young Asian girl desperate to escape from her family.When 14 -year-old Zeena begs to be taken into care with a non-Asian family, she is clearly petrified. But of what?Placed in the home of experienced foster carer Cathy and her family, Zeena gradually settles into her new life, but misses her little brothers and sisters terribly. Prevented from having any contact with them by her family who insist she has brought shame and dishonour on the whole community, Zeena tries to see them at school. But when her father and uncle find out, they bundle her into a car and threaten to set fire to her if she makes anymore trouble. Zeena is too frightened to press charges against them despite being offered police protection in a safe house.Eventually, Cathy discovers the devastating truth from Zeena, and with devastation she believes there is little she can do to help her.

(#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

Copyright (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the children.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2014

FIRST EDITION

© Cathy Glass 2014

A catalogue record of this book

is available from the British Library

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photography by Nicky Rojas (posed by model)

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780007590001

Ebook Edition © September 2014 ISBN: 9780007590018

Version: 2016-04-22

Contents

Cover (#u4af22811-27e4-530b-935f-4b667541a831)

Title Page (#u1a61c02d-2abc-50db-a07c-0b6c0efbb46e)

Copyright (#u1aa00aa6-c61e-51e2-a8ff-c1db5891e901)

Also by Cathy Glass (#ulink_d3e9bff2-4b5e-57cc-80a6-0da5411c739f)

Acknowledgements (#ulink_f2c58a6f-d035-539f-8234-5a433ed5a312)

Prologue (#ulink_5d3951a2-f906-533a-a6d3-9202b7be7994)

Chapter One: Petrified (#ulink_9b4647f9-d1fc-5135-9001-689205811ddb)

Chapter Two: Different House (#ulink_ce8cc55e-be63-53b4-b466-bcf8b940fc76)

Chapter Three: Good Influence (#ulink_a690ce59-5c7f-54cc-a8d9-2d1ca47f9701)

Chapter Four: Sobbing (#ulink_e1e832e4-a1af-5941-8343-5508e726e0b9)

Chapter Five: Scared into Silence (#ulink_3aba872c-fab4-5156-a718-4abff5cbd668)

Chapter Six: Dreadful Feeling (#ulink_d6248a15-6e77-5ed5-97ae-07b1fa5ef8ee)

Chapter Seven: Desperate (#ulink_df7275ca-31c9-5209-b726-b96d19ce8930)

Chapter Eight: Lost Innocence (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Ordeal (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: Optimistic (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Worries and Worrying (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: Only Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: Consequences (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: Review (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen: Vicious Threats (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen: Zeena’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen: A Special Holiday (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen: Overwhelmed (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen: Atrocity (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty: I Miss Hugs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One: Police Business (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Suitcase (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three: Other Victims (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Silence Was Deafening (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five: Heartbreaking (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six: Turn of Events (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven: More than I Deserve (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: Deserves the Best (#litres_trial_promo)

Contacts (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

Cathy Glass (#litres_trial_promo)

If you loved this book … (#litres_trial_promo)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#litres_trial_promo)

A note from The Fostering Network (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Cathy Glass (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

Damaged

Hidden

Cut

The Saddest Girl in the World

Happy Kids

The Girl in the Mirror

I Miss Mummy

Mummy Told Me Not to Tell

My Dad’s a Policeman (a Quick Reads novel)

Run, Mummy, Run

The Night the Angels Came

Happy Adults

A Baby’s Cry

Happy Mealtimes for Kids

Another Forgotten Child

Please Don’t Take My Baby

Will You Love Me?

About Writing and How to Publish

Daddy’s Little Princess

Acknowledgements (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

A big thank-you to my editor, Holly; my literary agent, Andrew; Carole, Vicky, Laura, Hannah, Virginia and all the team at HarperCollins.

Prologue (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

A small child walks along a dusty path. She has been on an errand for her aunt and is now returning to her village in rural Bangladesh. The sun is burning high in the sky and she is hot and thirsty. Only another 300 steps, she tells herself, and she will be home.

The dry air shimmers in the scorching heat and she keeps her eyes down, away from its glare. Suddenly she hears her name being called close by and looks over. One of her teenage cousins is playing hide and seek behind the bushes.

‘Go away. I’m hot and tired,’ she returns, with childish irritability. ‘I don’t want to play with you now.’

‘I have water,’ he says. ‘Wouldn’t you like a drink?’

She has no hesitation in going over. She is very thirsty. Behind the bush, but still visible from the path if anyone looked, he forces her to the ground and rapes her.

She is nine years old.

Chapter One

Petrified (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

‘And she wouldn’t feel more comfortable with an Asian foster carer?’ I queried.

‘No, Zeena has specifically asked for a white carer,’ Tara, the social worker, continued. ‘I know it’s unusual, but she is adamant. She’s also asked for a white social worker.’

‘Why?’

‘She says she’ll feel safer, but won’t say why. I want to accommodate her wishes if I can.’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said, puzzled. ‘How old is she?’

‘Fourteen. Although she looks much younger. She’s a sweet child, but very traumatized. She’s admitted she’s been abused, but is too frightened to give any details.’

‘The poor kid,’ I said.

‘I know. The child protection police office will see her as soon as we’ve moved her. She’s obviously suffered, but for how long and who abused her, she’s not saying. I’ve no background information. Sorry. All we know is that Zeena has younger siblings and her family is originally from Bangladesh, but that’s it I’m afraid. I’ll visit the family as soon as I’ve got Zeena settled. I want to collect her from school this afternoon and bring her straight to you. The school is working with us. In fact, they were the ones who raised the alarm and contacted the social services. I should be with you in about two hours.’

‘Yes, that’s fine,’ I said. ‘I’ll be here.’

‘I’ll phone you when we’re on our way,’ Tara clarified. ‘I hope Zeena will come with me this time. She asked to go into care on Monday but then changed her mind. Her teacher said she was petrified.’

‘Of what?’

‘Or of whom? Zeena wouldn’t say. Anyway, thanks for agreeing to take her,’ Tara said, clearly anxious to be on her way and to get things moving. ‘I’ll phone as soon as I’ve collected her from school.’

We said a quick goodbye and I replaced the handset. It was only then I realized I’d forgotten to ask if Zeena had any special dietary requirements or other special considerations, but my guess was that as Tara had so little information on Zeena, she wouldn’t have known. I’d find out more when they arrived. With an emergency placement – as this one was – the background information on the child or children is often scarce to begin with, and I have little notice of the child’s arrival; sometimes just a phone call in the middle of the night from the duty social worker to say the police are on their way with a child. If a move into care is planned, I usually have more time and information.

I’d been fostering for twenty years and had recently left Homefinders, the independent fostering agency (IFA) I’d been working with, because they’d closed their local branch and Jill, my trusted support social worker, had taken early retirement. I was now fostering for the local authority (LA). While it made no difference to the child which agency I fostered for, I was having to get used to slightly different procedures, and doing without the excellent support of Jill. I did have a supervising social worker (as the LA called them), but I didn’t see her very often, and I knew that, unlike Jill, she wouldn’t be with me when a new child arrived. It wasn’t the LA’s practice.

It was now twelve noon, so if all went to plan Tara and Zeena would be with me at about two o’clock. The secondary school Zeena attended was on the other side of town, about half an hour’s drive away. I went upstairs to check on what would be Zeena’s bedroom for however long she was with me. I always kept the room clean and tidy and with the bed made up, as I never knew when a child would arrive. The room was never empty for long, and Aimee, whose story I told in Another Forgotten Child, had left us two weeks previously. The duvet cover, pillow case and cushions were neutral beige, which would be fine for a fourteen-year-old girl. To help her settle and feel more at home I would encourage her to personalize her room by adding posters to the walls and filling the shelves with her favourite books, DVDs and other knick-knacks that litter teenagers’ bedrooms.

Satisfied that the room was ready for Zeena, I returned downstairs. I was nervous. Even after many years of fostering, awaiting the arrival of a new child or children is an anxious time. Will they be able to relate to me and my family? Will they like us? Will I be able to meet their needs, and how upset or angry will they be? Once the child or children arrive I’m so busy there isn’t time to worry. Sometimes teenagers can be more challenging than younger children, but not always.

At 1.30 the landline rang. It was Tara now calling from her mobile.

‘Zeena is in the car with me,’ she said quickly. ‘We’re outside her school but she wants to stop off at home first to collect some of her clothes. We should be with you by three o’clock.’

‘All right,’ I said. ‘How is she?’

There was a pause. ‘I’ll tell you when I see you,’ Tara said pointedly.

I replaced the receiver and my unease grew. From Tara’s response I guessed something was wrong. Perhaps Zeena was very upset. Otherwise Tara would have been able to reassure me that Zeena was all right instead of saying, ‘I’ll tell you when I see you.’

My three children were young adults now. Adrian, twenty-two, had returned from university and was working temporarily in a supermarket until he decided what he wanted to do – he was thinking of accountancy. Lucy, my adopted daughter, was nineteen, and was working in a local nursery school. Paula, just eighteen, was in the sixth form at school and had recently taken her A-level examinations. She was hoping to attend university in September. I was divorced; my husband, John, had run off with a younger woman many years previously, and while it had been very hurtful for us all at the time, it was history now. The children (as I still referred to them) wouldn’t be home until later, and I busied myself in the kitchen.

At 2.15 the telephone rang again. ‘We’re leaving Zeena’s home now,’ Tara said tightly. ‘Her mother had her suitcase packed ready. We’ll be with you in about half an hour.’

I thanked her for letting me know and replaced the receiver. I sensed there was trouble in what Tara had left unsaid, and I was surprised Zeena’s mother had packed her daughter’s case so quickly. She couldn’t have known for long that her daughter was going into care – Tara hadn’t known herself for definite until half an hour ago – yet she had spent that time packing. Usually parents are so angry when their child first goes into care (unless they’ve requested help) that they have to be persuaded to part with some of their child’s clothes and personal possessions to help them settle in at their carer’s. I’d have been less surprised if Tara had said there’d been a big scene at Zeena’s home and she wouldn’t be coming into care after all, for teenagers are seldom forced into care against their wishes, even if it is for their own good.

Now assured that Zeena was definitely on her way, I texted Adrian, Paula and Lucy: Zeena, 14, arriving soon. C u later. Love Mum xx.

I was looking out of the front-room window when, about half an hour later, a car drew up. I could see the outlines of two women sitting in the front, and then, as the doors opened and they got out, I went into the hall and to the front door to welcome them. The social worker was carrying a battered suitcase.

‘Hi, I’m Cathy,’ I said, smiling.

‘I’m Tara, Zeena’s social worker,’ she said. ‘Pleased to meet you. This is Zeena.’

I smiled at Zeena. ‘Come on in, love,’ I said cheerily.

Had I not known she was fourteen I’d have said she was much younger – nearer eleven or twelve. She was petite, with delicate features, olive skin and huge dark eyes. But what immediately struck me was how scared she looked. She held her body tense and kept glancing anxiously towards the road outside until I closed the front door. Then she put her hand on the door to test it was shut.

Tara saw this and asked me, ‘You do keep the door locked? It can’t be opened from the outside?’

‘Not without a key,’ I said.

‘Good. And there’s a security spy-hole,’ Tara said, pointing it out to Zeena. ‘So you or Cathy can check before you open the door.’

Zeena gave a small polite nod but didn’t look reassured. Clearly security was going to be an issue, and I felt slightly unsettled. Zeena slipped off her shoes and then lowered her headscarf, which had been draped loosely over her head. She had lovely long, black, shiny hair, similar to my daughter Lucy’s. It was tied back in a ponytail, which made her look even younger. She was wearing her school uniform, with leggings under her pleated skirt.

‘Leave the case in the hall for now,’ I said to Tara. ‘I’ll take it up to Zeena’s room later. Let’s go and sit down.’

Tara set the case by the coat stand and I led the way into the living room, which was at the rear of the house and looked out over the garden. When I fostered young children I always had toys ready to help take their minds off being separated from their parents, and on fine days the patio doors would be open. But not today – the air was chilly, although we were now in the month of May.

Tara sat on the sofa and Zeena sat next to her.

‘Would you like a drink?’ I asked them both.

‘Could I have a glass of water, please?’ Tara said. Then, turning to Zeena, she added, ‘Would you like one too?’

‘Yes, please,’ Zeena said quietly.

‘Or I have juice?’ I suggested.

‘Water is fine, thank you,’ Zeena said very politely.

I went into the kitchen, poured two glasses of water and, returning, placed them on the coffee table within their reach. I sat in one of the easy chairs. Tara drank some of her water, but Zeena left hers untouched. I could see how tense and anxious she was. It was as though she was on continual alert, ready to flee at a moment’s notice. I’d seen this before in children I’d fostered who’d been badly abused. They were always on their guard, listening out for any unusual sound and continually scanning their surroundings for signs of danger.

‘Thank you for looking after Zeena,’ Tara began, setting her glass on the coffee table. ‘This has all been such a rush I haven’t had a chance to look at your details properly and tell Zeena. You’ve got three adult children, I believe?’

‘Yes, one boy and two girls,’ I said, smiling at Zeena and trying to put her at ease. ‘You’ll meet them later.’

‘And you don’t have any other males in the house, apart from your son?’ Tara asked.

‘No. I’m divorced.’

She glanced at Zeena, who seemed to draw some comfort from this and gave a small nod. Tara had a nice manner about her, gentle and considerate. I guessed she was in her mid-thirties; she had short, wavy brown hair and was dressed in a long jumper over jeans.

‘Zeena is very anxious about her safety,’ Tara said to me. ‘She has a mobile phone, and I’ve put my telephone number in it, also the social services’ emergency out-of-hours number, and the police. It’s a pay-as-you-go phone. She has credit on it now. Can you make sure she keeps the phone in credit, please? It’s important for her safety.’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said, and felt my anxiety heighten.

‘Zeena knows she can phone the police at any time if she’s worried about her safety,’ Tara said. ‘Her family won’t be given this address. No one knows where she is staying, and the school know they mustn’t give out this address. We weren’t followed here, but please be cautious and check before answering the door.’

‘I always check at night,’ I said, uneasily. ‘But what am I checking for?’

Tara looked at Zeena.

‘My family,’ Zeena said very quietly, her hands trembling in her lap.

‘Please try not to worry,’ I said, feeling I should reassure her. ‘You’ll be safe here with me.’

Zeena’s eyes rounded in fear as she finally met my gaze, and I could see she dearly wished she could believe me. ‘I hope so,’ she said almost under her breath. ‘Because if they find me, they’ll kill me.’

Chapter Two

Different House (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

I looked at Tara. My mouth had gone dry and my heart was drumming loudly. I could see that Zeena’s comment had shaken Tara as much as it had me. Zeena had her head slightly lowered and was staring at the floor, wringing the headscarf she held in her lap. Suddenly the silence was broken by the sound of the front door opening. Zeena shot up from the sofa.

‘Who’s that?’ she cried.

‘It’s all right,’ I said, also standing. ‘That’ll be my daughter, Paula, back from sixth form.’

Zeena didn’t immediately relax and return to the sofa but remained standing, anxiously watching the living-room door.

‘We’re in here, love,’ I called to Paula, who was taking off her shoes and jacket in the hall.

Paula came into the living room, and I saw Zeena relax. ‘This is Zeena and her social worker, Tara,’ I said, introducing them.

‘Hi,’ Paula said, glancing at them both.

‘I’m pleased to meet you,’ Zeena said quietly. ‘Thank you for letting me stay in your home.’

I could see Paula was as touched as I was by Zeena’s politeness.

‘Do you think Paula could wait here with Zeena while we go and have a chat?’ Tara now asked me.

‘Sure,’ Paula said easily.

‘Thanks, love,’ I said. ‘We’ll be in the front room if we’re needed.’

Tara stood and Zeena returned to the sofa. Paula sat next to her. Both girls looked a little uncomfortable and self-conscious, but then teenagers often do when meeting someone new.

In the front room Tara closed the door so we couldn’t be overheard, and we sat opposite each other. Now she no longer needed to put on a brave and professional face for Zeena’s sake, she looked very worried indeed.

‘I don’t know what’s been going on at home,’ she began, with a small sigh. ‘But I’m very concerned. Zeena’s father and another man went to her school today. They were shouting and demanding to see Zeena. They only left when the headmistress threatened to call the police. Zeena was so scared she hid in a cupboard in the stockroom. It took a lot of persuading to get her to come out after they’d gone.’

‘What did they want?’ I asked, equally concerned.

‘I don’t know,’ Tara said. ‘But they’d come for Zeena. There was no sign of them when I arrived at the school, but Zeena begged me to take her out the back entrance in case they were still waiting at the front. As soon as we were in my car she insisted I put all the locks down and drive away fast. She phoned her mother from the car. It was a very heated discussion with raised voices, although I don’t know what was said as Zeena spoke in Bengali. She was distressed after the call but wouldn’t tell me what her mother had said. I’m going to have to take an interpreter with me when I visit Zeena’s parents.’

‘And Zeena won’t tell you why she’s so scared?’ I asked. ‘Or why she thinks her family want to kill her?’

‘No. I’m hoping the child protection police officer will have more success. She’s very good.’

‘The poor child,’ I said again. ‘She looks petrified. It’s making me nervous too.’

‘I know. I’m sorry to have to put you and your family through this. It seems to be escalating. But don’t hesitate to call the police if you need to.’ Which only heightened my unease.

‘Perhaps her parents will calm down once they accept Zeena is in care,’ I suggested, which often happened when a child was fostered.

‘Hopefully,’ Tara said. ‘Zeena told me in the car that she needed to see a doctor.’

‘Why? Is she hurt?’ I asked, concerned.

‘No. I asked her if it was an emergency – I would have taken her straight to the hospital, but she said she could wait for an appointment. Can you arrange for her to see a doctor as soon as possible, please?’

‘Yes, of course. Will she want to see her own doctor, or shall I register her with mine?’

‘We’ll ask her. When we stopped off to get her clothes her mother had the suitcase ready in the hall. She wouldn’t let Zeena into the house and was angry, although again I couldn’t understand what she was saying to Zeena. Eventually she dumped the case on the pavement and slammed the door in our faces. Zeena pressed the bell a few times, but her mother wouldn’t open the door again. When we got in the car Zeena told me she had asked her mother if she could say goodbye to her younger brothers and sisters, but her mother had refused and called her a slut and a whore.’

I flinched. ‘What a dreadful thing for a mother to say to her daughter.’

‘I know,’ Tara said, her brow furrowing. ‘And it raises concerns about the other children at home. I shall be checking on them.’

‘Will Zeena be going to school tomorrow?’ I thought to ask.

‘We’ll see how she feels and ask her in a moment.’ Tara glanced at her watch. ‘I think I’ve told you everything I know. Let’s go into the living room and talk to Zeena. Then I need to get back to the office and make some phone calls. At least Zeena has some clothes with her.’

‘Yes. That will help,’ I said. Often the children I looked after arrived in what they stood up in, which meant they had to make do from my supply of spares until I had the chance to go to the shops and buy them new clothes.

Paula and Zeena were sitting on the sofa, still looking self-conscious, but at least talking a little.

‘Thanks, love,’ I said to Paula, who now stood.

‘Is it OK if I go to my room?’ she asked. ‘Or do you still need me?’

‘No, do as you like,’ I said. ‘Thanks for your help.’

‘Thank you for sitting with me,’ Zeena said politely.

‘You’re welcome,’ Paula said, smiling at Zeena. ‘Catch up with you later.’ She left the room.

Tara returned to sit on the sofa and I took the easy chair.

‘I’ve explained to Cathy what happened at school this morning,’ Tara said to Zeena. ‘Also that you need to see a doctor.’

Zeena gave a small nod and looked down.

‘Would you like to see your own family doctor?’ Tara now asked her.

‘No!’ Zeena said, sitting bolt upright and staring at Tara. ‘No. You mustn’t take me there. Please don’t make me see him. I won’t go.’

‘All right,’ Tara said, placing a reassuring hand on her arm. ‘I won’t force you to see him, of course not. You can see Cathy’s doctor. I just wanted to hear your views. You may have preferred to see the doctor you knew.’

‘No!’ Zeena cried again, shaking her head.

‘I’ll arrange for you to see my doctor then,’ I said quickly, for clearly this was causing Zeena a lot of distress. ‘There are two doctors in the practice I use, a man and a woman. They are both lovely people and good doctors.’

Zeena looked at me. ‘Are they white?’ she asked.

‘Yes. But I can arrange for you to see an Asian doctor if you prefer. There is another practice not far from here.’

‘No!’ Zeena cried again. ‘I can’t see an Asian doctor.’

‘All right, love,’ I said. ‘Don’t upset yourself. But can I ask you why you want a white doctor? Tara told me you asked for a white foster carer. Is there a reason?’ I was starting to wonder if this was a form of racism, in which case I would find Zeena’s views wholly unacceptable.

She was looking down and chewing her bottom lip as she struggled to find the right words. Tara was waiting for her reply too.

‘It’s difficult for you to understand,’ she began, glancing at me. ‘But the Asian network is huge. Families, friends and even distant cousins all know each other and they talk. They gossip and tell each other everything, even what they are not supposed to. There is little confidentiality in the Asian community. If I had an Asian social worker or carer my family would know where I was within an hour. I have brought shame on my family and my community. They hate me.’

Zeena’s eyes had filled and a tear now escaped and ran down her cheek. Tara passed her the box of tissues I kept on the coffee table, while I looked at her, stunned. The obvious question was: what had she done to bring so much shame on her family and community? I couldn’t imagine this polite, self-effacing child perpetrating any crime, let alone one so heinous that she’d brought shame on a whole community. But now wasn’t the time to ask. Zeena was upset and needed comforting. Tara was lightly rubbing her arm.

‘Don’t upset yourself,’ I said. ‘I’ll make an appointment for you to see my doctor.’

She nodded and wiped her eyes. ‘Thank you. I’m sorry to cause you so much trouble when you are being so kind to me, but can I ask you something?’

‘Yes, of course, love,’ I said.

‘Do you have any Asian friends from Bangladesh?’

‘I have some Asian friends,’ I said. ‘But I don’t think any of them are from Bangladesh.’

‘Please don’t tell your Asian friends I’m here,’ she said.

‘I won’t,’ I said, as Tara reached into her bag and took out a notepad and pen. However, it occurred to me that Zeena could still be seen with me or spotted entering or leaving my house, and I thought it might have been safer to place her with a foster carer right out of the area, unless she was overreacting, as teenagers can sometimes.

Tara was taking her concerns seriously. ‘Remember to keep your phone with you and charged up,’ she said to Zeena as she wrote. ‘Do you have your phone charger with you?’

‘Yes, it’s in my school bag in the hall,’ Zeena said.

‘Will you feel like going to school tomorrow?’ I now asked – given what had happened at school today I thought it was highly unlikely.

To my surprise Zeena said, ‘Yes. The only friends I have are at school. They’ll be worried about me.’

Tara looked at her anxiously ‘Are you sure you want to go back there?’ We can find you a new school.’

‘I want to see my friends.’

‘I’ll tell the school to expect you then,’ Tara said, making another note.

‘I’ll take and collect you in the car,’ I said.

‘It’s all right. I can use the bus,’ Zeena said. ‘They won’t hurt me in a public place. It would bring shame on them and the community.’

I wasn’t reassured, and neither was Tara.

‘I’d feel happier if you went in Cathy’s car,’ Tara said.

‘If I’m seen in her car they will tell my family the registration number and trace me to here.’

Whatever had happened to make this young girl so wary and fearful, I wondered.

‘Use the bus, then,’ Tara said, doubtfully. ‘But promise me you’ll phone if there’s a problem.’

Zeena nodded. ‘I promise.’

‘I’ll give you my mobile number,’ I said. ‘I’d like you to text me when you reach school.’

‘That’s a good idea,’ Tara said.

There was a small silence as Tara wrote, and I took the opportunity to ask: ‘Zeena, do you have any special dietary needs? What do you like to eat?’

‘I eat most things, but not pork,’ she said.

‘Is the meat I buy from our local butchers all right?’

‘Yes, that’s fine. I don’t eat much meat.’

‘Do you need a prayer mat?’ Tara now asked her.

Zeena gave a small shrug. ‘We didn’t pray much in my family, and I don’t think I have the right to pray now.’ Her eyes filled again.

‘I’m sure you have the right to pray,’ I said. ‘Nothing you’ve done is that bad.’

Zeena didn’t reply.

‘Can you think of anything else you may need here?’ Tara asked her.

‘When you visit my parents could you tell them I’m very sorry, and ask them if I can see my brothers and sisters, please?’

‘Yes, of course,’ Tara said. ‘Is there anything you want me to bring from home?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘If you think of anything, phone me and I’ll try to get it when I visit,’ Tara said.

‘Thank you,’ Zeena said, and wiped her eyes. She appeared so vulnerable and sad, my heart went out to her.

Tara put away her notepad and pen and then gave Zeena a hug. ‘We’ll go and have a look at your room now before I leave.’

We stood and I led the way upstairs and into Zeena’s bedroom. It was usual practice for the social worker to see the child’s bedroom.

‘This is nice,’ Tara said, while Zeena looked around, clearly amazed.

‘Is this room just for me?’ she asked.

‘Yes. You have your own room here,’ I said

‘Do you share a bedroom at home?’ Tara asked her.

‘Yes.’ Her gaze went to the door. ‘Can I lock the door?’ she asked me.

‘We don’t have locks on any of the bedroom doors,’ I said. ‘But no one will come into your room. We always knock on each other’s bedroom doors if we want the person.’ Foster carers are advised not to fit locks on children’s bedroom doors in case they lock themselves in when they are upset. ‘You will be safe, I promise you,’ I added.

Zeena gave a small nod.

Tara was satisfied the room was suitable and we went downstairs and into the living room where Tara collected her bag.

‘Tell Cathy or phone me if you need anything or are worried,’ she said to Zeena. I could see she felt as protective of Zeena as I did.

‘I will,’ Zeena said.

‘Good girl. Take care, and try not to worry.’

Zeena gave a small, unconvincing nod and perched on the sofa while I went with Tara to the front door.

‘Keep a close eye on her,’ she said quietly to me so Zeena couldn’t hear. ‘I’m very worried about her.’

‘I will,’ I said. ‘She’s very frightened and anxious. I’ll phone you when I’ve made the doctor’s appointment.’

‘Thank you. I’ll be in touch.’

I closed the front door and returned to the living room where Zeena was on the sofa, bent slightly forward and staring at the floor. It was nearly five o’clock and Lucy would be home soon, so I thought I should warn Zeena so she wasn’t startled again when the front door opened.

‘You’ve met my daughter Paula,’ I said, sitting next to her. ‘Soon my other daughter, Lucy, will be home from work. Don’t worry if you hear a key in the front door; it will be her. Adrian won’t be home until about eight o’clock; he’s working a late shift today.’

‘Do all your children have front-door keys?’ Zeena asked, turning slightly to look at me.

‘Yes.’

‘I’m not allowed to have a key to my house,’ she said.

I nodded. Different families have different policies on this type of responsibility; however, by Zeena’s age most of the teenagers I knew had their own front-door key, as had my children.

‘What age will you have a key?’ I asked out of interest, and trying to make conversation to put her at ease.

‘Never,’ she said stoically. ‘The girls in my family don’t have keys to the house. The boys are given keys when they are old enough, but the girls have to wait until they are married. Then they may have a key to their husband’s house, if their husband wishes.’

Zeena had said this without criticism, having accepted her parents’ rules. I appreciated that hers was a different culture with slightly different customs. I had little background information on Zeena, so as she’d mentioned her siblings I thought I’d ask about them.

‘How many brothers and sisters do you have?’

‘Four,’ she said. ‘Two brothers and two sisters.’

‘How lovely. I think Tara told me they’re all younger than you?’

‘Yes, I am the eldest. The boys are aged ten and eight, and my sisters are five and three. They’ll miss me. I’m like a mother to them.’ Her eyes filled again and I gently touched her arm.

‘Tara said she’d speak to your parents about you seeing your brothers and sisters,’ I reassured her. ‘Do you have any photographs of them?’

‘Not with me; they’re at home.’

‘We could ask Tara to get some when she visits your parents?’ I suggested. I usually tried to obtain a few photographs of the child’s natural family, as it helped them to settle and also kept the bond going while they were separated. ‘Shall I phone Tara and ask her?’

‘I can text her,’ Zeena said.

She now drank some of her water and finally allowed her gaze to wander around the room and out through the patio windows to the garden beyond.

‘You have a nice home,’ she said, delicately holding the glass in her hands.

‘Thank you, love. I want you to feel at home here. I know it’s probably very different from your house, and our routines will be different too, so you must tell me if there is anything you need.’

‘Thank you,’ she said, and set her glass on the coffee table. ‘I expect I’ll have to ask you lots of questions,’ she added quietly.

‘That’s fine. Do you have any questions now?’

She looked at the clock on the mantelpiece. ‘Yes. What time would you like me to serve you dinner?’

Chapter Three

Good Influence (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

‘Serve dinner?’ I asked, thinking I’d misheard. ‘What do you mean?’

‘What time shall I make your evening meal?’ Zeena said, rephrasing the question.

‘You won’t make our evening meal,’ I said. ‘Do you mean you’d like to make your own?’ This seemed the most likely explanation.

‘No. I have to cook for you and your family,’ Zeena said.

‘Whatever gave you that idea?’ I asked.

‘I cook for my family at home,’ she said. ‘So I thought it would be the same here.’

‘No, love,’ I said. ‘I wouldn’t expect you or any child I looked after to cook for us. You can certainly help me, if you wish, and if there’s something I can’t make that you like, then tell me. I’ll buy the ingredients and we can cook it together.’

Zeena looked at me, bemused. ‘Do your daughters do the cooking?’ she asked.

‘Sometimes, but Lucy’s at work and Paula is at sixth form. They help at weekends. Adrian does too.’

‘But Adrian is a man,’ she said, surprised.

‘Yes, but there’s nothing wrong in men cooking. Many of the best chefs are men. How often do you cook at home?’

‘Every day,’ Zeena said.

‘The evening meal?’

‘Yes, and breakfast. At weekends I cook lunch too. In the evenings during the week I also make lunch for my youngest sister who doesn’t go to school, and my mother heats it up for her.’

While I respected that individual cultures did things in their own way and had different expectations of their children, this seemed a lot for a fourteen-year-old to do every day. ‘Does your mother go out to work?’ I asked, feeling this might be the explanation.

‘No!’ Zeena said, shocked. ‘My father wouldn’t allow her to go out to work. Sometimes she sews at home, but sometimes she is ill and has to stay in bed.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ I said. ‘I hope she fully recovers soon.’

Zeena gave a small shrug. ‘She has headaches. They come and go.’

It didn’t sound as though her mother was very ill, and Zeena didn’t appear too worried about her. I was pleased she was talking to me. It was important we got to know each other. The more I knew about her, the more I should be able to help her.

‘Shall we take your case up to your room now?’ I suggested. ‘You’ll feel more settled once you’re unpacked and have your things around you.’

‘Yes. I’m sorry I’m such a burden. It’s kind of you to let me stay.’

‘You’re not a burden, far from it,’ I said, placing my hand lightly on her arm. ‘I foster children because I want to. We’re all happy to have you stay.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Positive.’

‘That’s very kind of you.’ She was so unassuming and grateful I was deeply touched.

We stood, but as we left the living room to go down the hall a key sounded in the front door. Zeena froze before she remembered. ‘Is that your other daughter?’

‘Yes, it’s Lucy. Come and say hello.’

We continued down the hall as Lucy let herself in.

‘This is Zeena,’ I said.

‘Hi, good to meet you,’ Lucy said easily, closing the door behind her. ‘How are you doing?’

‘I’m well, thank you,’ Zeena said politely. ‘How are you?’

‘Good.’

I kissed Lucy’s cheek as I always did when she returned home from work. ‘I’m taking Zeena’s case up to her room,’ I said. ‘Then I’ll start dinner.’

‘Is Paula back?’ Lucy asked, kicking off her shoes.

‘She’s in her room.’

‘Great! She’ll be pleased. I’ve got tickets for the concert!’

Lucy flew up the stairs excitedly, banged on Paula’s door and went in. ‘Guess what!’ we heard her shout. ‘The tickets are booked! We’re going!’ There were whoops of joy and squeals of delight from both girls.

‘They’re going to see a boy-band concert,’ I explained to Zeena.

She smiled politely.

‘They go a couple of times a year, when there is a group on they want to see. If you’re still here with us, you could go with them next time,’ I suggested.

‘My father won’t allow me to go to concerts,’ she said. ‘Some of my friends at school go, but I can’t.’

‘Maybe when you are older he’ll let you go,’ I said cheerfully, and picked up her case.

Zeena gave a small shrug but didn’t reply, and I led the way upstairs and into her room.

‘I’m pleased you’ve got some of your clothes with you,’ I said, positively. ‘I’ve plenty of spare towels and toiletries if you need them.’

‘Thank you.’

Zeena set the case on her bed, but then struggled to open the sliding lock. It wasn’t locked but the old metal fastener was corroded. I helped her and between us we succeeded in releasing the catch. She lifted the lid on the case and cried out in alarm. ‘Oh no! Mum has packed the wrong clothes.’ The colour drained from her face.

I looked into the open case. On top was what appeared to be a long red beaded skirt in a see-through chiffon material. As Zeena pushed this to one side and rummaged beneath, I saw some short belly tops in silky materials, glittering with sequins. I also saw other skirts and what looked like pantaloons, all similarly embroidered with sequins and beads, similar to the clothes Turkish belly-dancers wear. Zeena dug to the bottom of the case and then closed the lid.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked. She was clearly upset.

‘Mum hasn’t packed my jeans or any of my ordinary clothes,’ she said, flustered and close to tears.

‘What are these clothes for, then?’ I asked, puzzled.

‘I don’t know,’ she replied. ‘They’re not mine.’

I looked at her, confused. ‘What do you wear when you’re not in your school uniform?’ I asked.

‘Jeans, leggings, T-shirts – normal stuff.’

‘I see,’ I said, no less confused but wanting to reassure Zeena. ‘Don’t worry, I keep spares. I can find you something to wear until we can get your own clothes from home. I guess your mother made a mistake.’

Zeena’s bottom lip trembled. ‘She did it on purpose,’ she said.

‘But why would your mother give you the wrong clothes on purpose?’ I asked.

Zeena shook her head. ‘I can’t explain.’

I’d no idea what was going on, but my first priority was to reassure Zeena. She was visibly shaking. ‘Don’t worry, love,’ I said. ‘I’ve got plenty of spares that will fit you. I can wash and dry your school uniform tonight and it will be ready for tomorrow.’

‘I can’t believe she’d do that!’ Zeena said, staring at the case.

Clearly there was more to this than her mother simply packing the wrong clothes, but I couldn’t guess what message was contained in those clothes, and Zeena wasn’t ready to talk about it now.

‘I’ll phone my mother and tell her I’ll go tomorrow and collect my proper clothes,’ Zeena said anxiously.

‘Do you think that’s wise?’ I asked, concerned. ‘Perhaps we should wait, and ask your social worker to speak to your mother?’

‘No. Mum won’t talk to her. My phone and charger are in my school bag in the hall. Is it all right if I get them?’

‘Yes, of course, love. You don’t have to ask.’

As Zeena went downstairs to fetch her school bag I went round the landing to my bedroom where I kept an ottoman full of freshly laundered and new clothes for emergencies. I knew I needed to tell Tara the problem with the clothes and that Zeena was going to see her mother. I would also note it in my fostering log. All foster carers keep a daily log of the child or children they are looking after. It includes appointments, the child’s health and well-being, significant events and any disclosures the child may make about their past. When the child leaves, this record is placed on file at the social services and can be looked at by the child when they are an adult.

I lifted the lid on the ottoman and looked in. Zeena was more like a twelve-year-old in stature, and I soon found a pair of leggings and a long shirt that would fit her to change into now, and a night shirt and new underwear. Closing the lid I returned to her room. She had moved her suitcase onto the floor and was now sitting on her bed with her phone plugged into the charger, and texting. In this, at least, she appeared quite comfortable.

‘I think these will fit,’ I said, placing the clothes on her bed. ‘Come down when you’re ready, love.’

‘Thank you,’ she said absently, concentrating on the text message.

I went into Paula’s room where she and Lucy were still excitedly discussing the boy-band concert, although it wasn’t for some months yet.

‘When you have a moment could you look in on Zeena, please?’ I asked them. ‘She’s feeling a bit lost at present. I’m going to make dinner.’

‘Sure will,’ Lucy said.

‘She seems nice,’ Paula said.

‘She is. Very nice,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry, we’ll look after her,’ Lucy added. Lucy had come to me as a foster child eight years before and therefore knew what if felt like to be in care. She was now my adopted daughter.

I left the girls and went downstairs. I was worried about Zeena and also very confused. I thought the clothes in the case were hers, although they seemed rather revealing and immodest, considering her father appeared to be so strict. But why had her mother sent them if Zeena couldn’t wear them? It didn’t make sense. Hopefully, in time, Zeena would be able to explain.

Downstairs in the kitchen I began the preparation of dinner. I was making a pasta and vegetable bake. Zeena had said she ate most foods but not a lot of meat. I’d found in the past with other children and young people I’d fostered that pasta was a safe bet to begin with.

After a while I heard footsteps on the stairs, and then Zeena appeared in the kitchen. She was dressed in the leggings and shirt and was carrying her school uniform.

‘They fit you well,’ I said, pleased.

‘Yes, thank you. Where shall I wash these?’ she asked.

‘Just put them in the washing machine,’ I said, nodding to the machine. ‘I’ll see to them.’

Zeena loaded her clothes into the machine and then began studying the dials. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘It’s different from the one we have at home. Can you show me how it works, please?’

‘Do you do the washing at home, then?’ I asked as I left what I was doing and went over.

‘Yes. My little brothers and sisters get very messy,’ Zeena said. ‘Mother likes them looking nice. I don’t mind the washing – we have a machine. I wish it ironed the clothes as well.’ For the first time since she’d arrived, a small smile flicked across her face.

I smiled too. ‘Agreed!’ I said as I tipped some powder into the dispenser, and set the dial. ‘Although many of our clothes are non-crease, and Lucy and Paula usually iron their own clothes.’

‘And your son?’ Zeena asked, looking at me. ‘He doesn’t iron his clothes, surely?’

‘Not yet,’ I said lightly. ‘But I’m working on it.’

Zeena smiled again. She was a beautiful child and when she smiled her whole face lit up and radiated warmth and serenity.

‘There’s a laundry basket in the bathroom,’ I said. ‘In future, you can put your clothes in that and I’ll do all our washing together.’

‘Thank you. I don’t want to be any trouble.’

‘You’re no trouble,’ I said.

Zeena hesitated as if about to add something, but then changed her mind. ‘I tried to phone my mother,’ she said a moment later. ‘But she didn’t answer. I’ll try again now.’

‘All right, love.’

She left the kitchen and I heard her go upstairs and into her bedroom. I finished preparing the pasta bake, put it into the oven and then laid the table. A short while later I heard movement upstairs and then the low hum of the girls’ voices as the three of them talked. I was pleased they were getting to know each other. I’d found in the past that often the child or young person I was fostering relaxed and got to know my children before they did me.

Presently I called them all down for dinner and they arrived together.

‘Zeena phoned her mum,’ Lucy said. ‘She’s going to collect her clothes tomorrow.’

‘And your mum was all right with you?’ I asked Zeena.

She gave a small nod but couldn’t meet my eyes, so I guessed her mother hadn’t been all right with her but she didn’t want to tell me.

‘Does she always speak in Bengali?’ Lucy asked, sitting at the table.

‘Yes,’ Zeena said.

‘Can she speak English?’ Paula asked, also sitting at the table.

‘A little,’ Zeena said. ‘But my father insists we speak Bengali in the house, so Mum doesn’t get much chance to practise her English.’

‘You’re very clever speaking two languages fluently,’ Paula said. ‘I struggled with French at school.’

‘It’s easy if you are brought up speaking two languages,’ Zeena said.

While Paula and Lucy had sat at the table ready for dinner, Zeena was still hovering. ‘Sit down, love,’ I called from the kitchen.

‘I should help you bring in the meal first,’ Zeena said.

Lucy and Paula looked at each other guiltily. ‘So should we,’ Lucy said.

‘It’s OK. The dish is very hot,’ I said. ‘You sit down, pet.’

Zeena sat beside Paula and opposite Lucy. Using the oven gloves I carried in the dish of pasta bake and set in on the pad in the centre of the table, next to the bowl of salad. I returned to the kitchen for the crusty French bread, which I’d warmed in the oven, and set that on the table too.

‘Mmm, yummy,’ Paula said, while Lucy began serving herself.

‘It’s just pasta, vegetables and cheese,’ I said to Zeena. ‘Help yourself. I hope you like it.’

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘I’m sure I will.’

When a child first arrives, mealtimes can be awkward for them. Having to sit close to people they don’t know and eat can be quite intimidating, although I do all I can to make them feel at ease. Some children who’ve never had proper mealtimes at home may have never sat at a dining table or used cutlery, so it’s a whole new learning experience for them. However, this wasn’t true of Zeena. As we ate I could see that Lucy and Paula were as impressed as I was by her table manners. She sat upright at the table and ate slowly and delicately, chewing every mouthful, and never spoke and ate at the same time. Every so often she would delicately dab her lips with her napkin. All her movements were so smooth and graceful they reminded me of a beautiful swan in flight or a ballet dancer.

When she’d finished she paired her cutlery noiselessly in the centre of her plate and sipped her water. ‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘It’s such a treat to be cooked for.’

‘Good. I’m pleased.’ I smiled.

We just had fruit and yoghurt for dessert and Zeena thanked me again. Then we stayed at the table and talked for a while. Lucy did most of the talking and kept us entertained with anecdotes about the children she looked after at the nursery. A couple of times Zeena joined in with reminiscences about one of her younger siblings, but she looked sad when she spoke of them, and said she missed them and they would miss her. I reassured her again that Tara would try to arrange for her to see them as soon as possible. Zeena’s mobile phone had been on her lap during dinner and while I didn’t usually allow phones, game consoles or toys at the meal table, it was Zeena’s first night and I hadn’t said anything. It now rang.

‘Excuse me,’ she said, standing, and left the room to take the call.

We could hear her talking in the hall in a mixture of Bengali and English, effortlessly alternating between the languages as bilingual people can do. We didn’t listen but continued our conversation, with Zeena’s voice in the background.

‘We were with Zeena when she spoke to her mother before,’ Lucy said. ‘I don’t know what her mother said to her but it wasn’t good.’

‘What makes you say that?’ I asked.

‘Zeena was upset and her mum sounded angry on the phone.’

‘Why is she in care?’ Paula asked.

‘Zeena asked to come into care,’ I said. ‘She hasn’t told the social worker what happened; only that she’s been abused.’

‘Oh dear,’ Paula said sadly.

‘Zeena needs to start talking about what happened to her,’ Lucy said, speaking from experience.

‘I know,’ I said. ‘If she does tell you anything, remember you need to persuade her to tell me.’

The girls nodded solemnly. Sometimes the child or young person we were fostering disclosed the abuse they’d suffered to my children first. Lucy, Paula and Adrian knew they had to tell me if this happened so that I could alert the social worker and better protect the child. It was distressing for us all to hear these disclosures, but it was better for the child when they began to unburden themselves and share what had happened to them, as Lucy knew.

When Zeena had finished her telephone call she didn’t return to sit with us but went straight up to her room. I gave her a few minutes and then I went up to check she was all right. Her door was open so I gave a brief knock and went in. She was sitting on the bed with her phone in her hand, texting. ‘Are you OK?’ I asked.

‘Yes, thank you.’ She glanced up. ‘I’m texting my friends from school.’

‘As long as you are all right,’ I said, and came out.

I returned downstairs to find Lucy and Paula clearing the table and stacking the dishwasher. ‘We should help you more,’ Paula said.

‘Starting from now, we will,’ Lucy added.

I thought that Zeena’s stay was going to have a very good influence on them!

Shortly before eight o’clock Adrian arrived home. All three girls and I were in the living room watching some television when we heard a key go in the front-door lock and the door open. ‘It’s my son, Adrian,’ I reminded Zeena as she instinctively tensed.

‘Oh, yes,’ she said, relieved.

I went down the hall to greet him and then we returned to the living room so he could meet Zeena. She stood as we entered and Adrian went over and shook her hand. ‘Very pleased to meet you,’ he said.

‘And you,’ she said, shyly.

At twenty-two he was over six feet tall and towered over the rest of us, especially Zeena, who was so petite she looked like a doll beside him.

‘I hope you’re settling in,’ he said to her.

‘Yes, thank you,’ she said, again shyly.

Adrian then said hi to Lucy and Paula and went to shower before eating. The girls and I watched the news on television and then Zeena asked me if it was all right if she had an early night.

‘Of course, love,’ I said. ‘You must be exhausted. I’ll show you where everything is in the bathroom and get you some fresh towels.’

‘Thank you. It’s strange not having to put my little brothers and sisters to bed,’ she said as we went down the hall.

‘I’m sure they’ll be fine. Your mum will look after them.’

‘I hope so,’ she said, thoughtfully.

At the foot of the stairs Zeena suddenly put her hand on my arm. ‘Do you lock the back door as well as the front door at night?’ she asked anxiously.

‘Yes, and bolt it. Don’t worry, you’re safe here.’

‘What about the windows?’ she asked. ‘Are those locked too?’

‘No, but they can’t be opened from the outside.’

I looked at her; she was scared, and worried for her safety, but why?

‘Trust me, love,’ I said. ‘No one can get in.’

‘Thank you. I’ll try to remember that,’ she said.

Chapter Four

Sobbing (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

Zeena slept well that night, although I didn’t. I’m always restless the first few nights after a new child arrives, listening out in case they are out of bed or upset and need reassuring. Nevertheless, I was awake as usual at six o’clock and fell out of bed and into the shower while the rest of the house slept. When I came out, dressed, I was surprised to see Zeena on the landing in her nightshirt and looking very worried.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked her quietly, so as not to wake the others.

‘I’m sorry,’ she whispered. ‘I should have set the alarm on my phone.’

‘It’s only early,’ I said. ‘I was going to wake you at seven when I wake Lucy and Paula.’

‘But I have to do my chores before I go to school,’ she said.

‘What chores?’ I asked.

‘The ironing, and cleaning the house. I always do that before I go to school.’

To have a teenager up early and expecting to do the housework was a first for me, although there was a more serious side to this.

‘Is that what you do at home?’ I asked.

‘Yes. I do the ironing and cleaning before I get the little ones up or they slow me down and I’m late for school.’

The expectations I had in respect of the household duties a fourteen-year-old should be responsible for were clearly very different from those of Zeena’s parents, and I realized it would help Zeena if I explained to her what my expectations were.

‘While you’re here,’ I said, still keeping my voice low, ‘I expect you to keep your bedroom clean and tidy, but not the rest of the house. You can help me with the cooking and cleaning, but the main responsibility for the housework is mine. If I need help, which I will do sometimes, I’ll ask you, or Adrian, Lucy or Paula. Is that all right?’

‘Yes. It’s different in my home,’ she said.

‘I understand that.’ I smiled reassuringly.

She hesitated. ‘Shall I make my lunch now or later?’

‘When I asked you yesterday about lunch I thought you said you had a school dinner?’

‘Yes, but my father used to give me the money for it, and he won’t be doing that now.’

‘I should have explained,’ I said. ‘I’ll give you the money for your school dinner. And also for your bus fare and anything else you need while you’re here. You’ll also have a small allowance for clothes and pocket money, which I’ll sort out at the weekend. As a foster carer I receive an allowance towards this, so don’t worry, you won’t go short of anything.’

‘Thank you so much,’ she said. ‘What shall I do now?’

‘It’s up to you, love. It’s early, so you can go back to bed if you wish.’

‘Really? Can I listen to music on my phone?’

‘Yes, as long as you don’t disturb the others.’

‘I’ll use my earphones. Thank you so much,’ she said. She went to her room with the gratitude of someone who’d just received a much-wanted gift, which in a way I supposed she had: the gift of time. For without doubt at home Zeena had precious little time to herself, and the more I learned – even allowing for cultural differences – the more I felt her responsibilities were excessive for a child of her age. I’d mention it to Tara when we next spoke.

At seven o’clock I knocked on the girls’ bedroom doors to wake them. Adrian, having worked an evening shift, didn’t have to be up until 9.30 to start work at 10.30. I gave Zeena her freshly laundered school uniform, checked she had everything she needed and left her to wash and dress. Zeena, Lucy and Paula would take turns in the bathroom and then arrive downstairs for breakfast as they were ready. When my children were younger I used to make breakfast for us all and we ate together, but now they were older they helped themselves to cereal and toast or whatever they fancied, while I saw to the child or children we were fostering. We all ate together as much as possible in the evenings and at weekends.

When Zeena came down washed and dressed in her school uniform, I asked her what she liked for breakfast. She said she usually had fruit and yoghurt during the week, and eggs or chapri (a type of pancake) at the weekend. I showed her where the fruit and yoghurt were and she helped herself. I then sat at the table with her and made light conversation while we ate. I also asked her if she needed me to buy her anything, as I could easily pop to the local shops, but she said she didn’t think so as she would collect what she needed from home after school.

‘Are you sure you’ll be all right going home alone?’ I asked her, still concerned that this wasn’t the right course of action.

‘Yes. Mum said it was all right for me to have some of my things.’

‘Why didn’t she give them to you yesterday instead of packing clothes you couldn’t wear?’ I asked, baffled.

Zeena concentrated on her food as she replied. ‘I guess she made a mistake,’ she said quietly. It seemed an odd mistake to me, and that wasn’t what Zeena had said when she’d opened the case, but I didn’t challenge her; I let it go.

Lucy left first to go to work and as usual she was five minutes late. Calling a hurried goodbye from the hall she slammed the door with such haste that the whole house shook. I was used to it but it made Zeena jump. It was a regular week-day occurrence. Lucy had tried setting her alarm five minutes early, but then compensated by allowing herself another five minutes in bed. She was never late for work as far as I knew; it just meant she left the house in a rush every morning and then had to run to catch the bus. She told me a car was the answer, and I told her she’d better start saving.

When it was time for Zeena to leave I gave her the money she needed for her bus fare and lunch, as well as some extra. Again I offered to take her to school in my car, but she said she’d be all right on the bus and promised to text me to say she’d arrived safely.

‘All right, if you’re sure,’ I said, and opened the front door.

She had the navy headscarf she’d worn when she’d first arrived around her shoulders and draped it loosely over her head as she stepped outside. I went with her down the front-garden path to see her off and also check that there were no strangers loitering suspiciously in the street. Although Zeena seemed more relaxed about her security this morning after a good night’s sleep, I still had Tara’s words about being vigilant ringing in my ears. As a foster carer I’d been in this position before when an angry parent had found out where their child had been placed and was threatening to come to my house. But with Zeena believing her life was in danger, this had reached a whole new level.

As far as I could see the street was clear. Zeena kissed me goodbye and then I watched her walk up the street until she disappeared from sight. The bus stop was on the high road, about a five-minute walk away.

Paula left for sixth-form at 8.30. Then a few minutes later the landline rang. I answered it in the kitchen where I was clearing up and was surprised to hear from Tara so early in the morning. She was calling from her mobile and there was background noise.

‘I’m on the bus, going to work,’ she said. ‘I’ve been worrying about Zeena all night and wanted to check she’s OK.’

It must be very difficult for social workers to switch off after leaving work, I thought.

‘She’s all right,’ I said. ‘She’s on her way to school now. I asked her again if I could drive her but she wanted to go by bus. She promised she’d text me when she gets there. She seemed a bit brighter this morning.’

‘Good,’ Tara said. ‘And she got some sleep and has had something to eat?’

‘Yes. And she’s getting on well with my daughters, Lucy and Paula.’

‘Excellent.’

‘There are a few issues I need to talk to you about though,’ I said. ‘Shall I tell you now or would it be better if I called you when you’re in your office?’ I was mindful of confidentiality; Tara was on a bus and might be overheard.

‘Go ahead,’ Tara said. ‘I can listen, although I may not be able to reply.’

‘Zeena’s clothes,’ I began. ‘You remember the suitcase she brought from home?’

‘Yes.’

‘When we opened the case yesterday evening we found it was full of lots of flimsy skirts and belly tops with sequins and beads. Zeena can’t wear any of them. She seemed shocked, and said her mother had packed the wrong clothes on purpose. Then she said the clothes weren’t hers, and this morning she said it must have been a mistake. I’ve no idea whose clothes they are or what they are for, but she can’t wear them.’

‘Strange,’ Tara said. ‘And she can’t wear any of them?’

‘No. I’ve given her what she needs from my spares. I offered to go shopping and buy her what she needs, but she says she’s going home after school to collect some of her proper clothes.’

‘I’m not sure that’s wise,’ Tara said.

‘That what I said. I suggested she speak to you, but she telephoned her mother and apparently she is all right about Zeena going over for her things. However, Lucy said that her mother sounded angry on the phone, although she didn’t know what she’d said.’

‘Thanks. I’ll phone Zeena,’ Tara said, even more concerned. Then, lowering her voice so she couldn’t be overheard, she added, ‘Has Zeena said anything to you about the nature of the abuse she’s suffered?’

‘No, but she has told me a bit about her home life. Are you aware of all the responsibility she has – for the cooking, cleaning, ironing and looking after her younger siblings?’

‘No. I hardly know anything about the family. They’ve never come to the notice of the social services before. What has Zeena said?’

I now repeated what Zeena had told me, and also that she’d been up early, expecting to clean the house before she went to school. As a foster carer I’m duty-bound to tell the social worker what I know and to keep him or her regularly informed and updated, as they are legally responsible for the child while in care. The child or children I foster know I can’t keep their secrets, and if they tell me anything that is important to their safety or well-being then I have to pass it on so the necessary measures can be taken to protect and help them.

‘It does seem excessive,’ Tara said when I’d finished. ‘I know that the eldest girl in some Asian families often has more responsibility for domestic chores than her younger siblings, or the boys, but this sounds extreme. I’ll raise it when I see her parents, which I’m hoping to do soon. Thanks, Cathy. Was there anything else?’

‘I don’t think so. I’ll make the doctor’s appointment as soon as the practice opens.’

‘Thank you. I’ll phone Zeena now. I also want to speak to her school.’

She thanked me again and we said goodbye. Tara came across as a very conscientious social worker who genuinely cared about the children she was responsible for and would go that extra mile. That she’d telephoned me on her way into work because she was worrying about Zeena said it all. She was as concerned as I was about her using the bus, and when Zeena hadn’t texted me by 8.50 a.m. – the time she should have arrived at school – my concerns increased.

I gave her until 9.00 a.m. and then texted her: R u at school? Cathy x.

She replied immediately: Srry. 4got 2 txt. I’m here with friends x.

I breathed a sigh of relief.

I now telephoned my doctor’s practice to make the appointment for Zeena. The doctors knew I fostered and I’d registered other children I’d looked after with them before, using a temporary patient registration, which could be converted into a permanent registration if necessary. This was how I registered Zeena over the phone. A registration card would need to be completed at the first visit. As Zeena’s appointment wasn’t an emergency and to save her missing school, I took the first evening slot that was available – five o’clock on Tuesday. It was Thursday now, so not long to wait. I thanked the appointments’ secretary, noted the time and date in my diary and then woke Adrian with a cup of tea.

‘You spoil me, Mum,’ he mumbled, reaching out from under the duvet for the cup.

‘I know. Don’t spill it,’ I said. ‘Time to get up.’

Since Adrian had returned from university and was working irregular hours I’d got into the habit of waking him for work with a cup of tea, although I’d assured him it was a treat that could be stopped if he didn’t clear up his room. And while we both saw the humour in little me disciplining a big lad of twenty-two (he had been known to pick me up when I was telling him off), like many young adults he still needed some guidelines. I’d read somewhere that the brain doesn’t completely stabilize until the age of twenty-five, and I’d mentioned this to all three of my children at some point.

I had coffee with Adrian while he ate his breakfast and then he went to work. I was tempted to text Zeena to make sure she was all right, but I thought she would be in her lessons now, when her phone should have been switched off and in her bag. I waited until twelve o’clock, which I thought might be the start of her lunch break to text: Hi, is everything all right? Cathy x.

It was twenty minutes before she texted back and I was worrying again: Yes. I’m ok. Thnk u x.

Tara telephoned an hour later. She’d spoken to Zeena earlier and had agreed that she could go home to collect her clothes and see her siblings, but told her to call her, me or the police if there was a problem.’

‘To be honest, Cathy,’ Tara said, ‘at her age, I can’t really stop her from going home if she’s determined. So it’s better to put in place some safeguards rather than just say no. Zeena seems sensible and I’m sure she won’t go into the house if she doesn’t feel safe.’

I agreed.

Tara then said she had telephoned Zeena’s school and had given them my contact details, and she’d been trying to make an appointment to visit Zeena’s parents, but no one was answering the landline, which was the only number she had for them. ‘Zeena tells me her mother doesn’t answer the phone unless she’s expecting a call from a relative,’ Tara said. ‘Apparently her father makes all the calls, but he isn’t home until the evening. If I can’t get hold of them I’ll just have to turn up. Also, I’ve spoken to the child protection police officer and given her your telephone number. She’ll phone you to make an appointment to see Zeena. I’ve also spoken to the head teacher at the primary school Zeena’s siblings attend, as there maybe some safeguarding issues there.’ This was normal social-work practice – if there were concerns about one child in a family then other children in the family were seen and assessed too, and part of this involved contacting their school and their doctor.

‘Thank you,’ I said, grateful for the update. ‘You have been busy.’

‘I’ve been on this case all morning,’ Tara said. ‘I’m in a meeting soon and then I have a home visit for another case. Zeena should be at her parents by three forty-five – her home is only a ten-minute walk from the school. I’ve suggested she spends no more than an hour there – to collect what she needs and see her siblings – so she should be with you by half past five. If there’s a problem, call me on my mobile.’

‘I will,’ I said. ‘I’ve made a doctor’s appointment for Zeena at five o’clock on Tuesday.’

‘Thanks,’ Tara said, and then asked for the name and contact details of my doctor’s practice, which I gave her.

Tara repeated again that if there was a problem I should phone her, but otherwise she’d be in touch again when she had any more news, and we said goodbye.

I spent the rest of the afternoon making notes in preparation for foster-carer training I was due to deliver on Monday. As an experienced carer I helped run training for newer carers as part of the Skills to Foster course. I’d been doing similar for Homefinders and when I’d transferred to the local authority they’d asked me to participate in their training. With this, fostering, some part-time administration work I did on an as-and-when basis, running the house and looking after everyone’s needs, I was busy and my days were full, but pleasantly so. I’d never remarried after my divorce but hadn’t ruled out the possibility; it was just a matter of finding the right man who would also commit to fostering.

Presently I heard a key go in the front door. Paula was home. ‘Hi, Mum,’ she called letting herself in. ‘Guess what?’

I packed away my papers as Paula came into the living room. ‘Adrian phoned,’ she said excitedly. ‘There’s some student summer work going at the place where he works. He said if I’m interested to put in my CV as soon as possible.’

‘Great,’ I said. ‘That sounds hopeful.’ Paula had been looking for summer work for a while. As well as giving her extra money the work experience would look good on her CV and help to take her mind off her A-level results, which weren’t due for another three months.

‘I’ll print out my CV now,’ she said. ‘And write a covering letter.’

‘Yes, and in the letter include the date you can start work,’ I suggested. ‘The twenty-second of July – when school officially finishes.’ Although Paula had sat her exams she was still expected to attend the sixth form until the end of term. ‘I’ll help you with the letter if you like,’ I added.

‘Thanks.’

She returned down the hall and to the front room where we kept the computer. As she did so the front doorbell rang. I glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece; it was half past four – too early for Zeena, I thought.

‘I’ll get it,’ Paula called.

‘Thanks. Don’t forget to check the security spy-hole first,’ I reminded her.

‘I know,’ she called. Then, ‘It’s Zeena, Mum.’

‘Oh,’ I said, surprised. I went into the hall as Paula opened the front door and Zeena came in, carrying a large laundry bag and sobbing her heart out.

Chapter Five

Scared into Silence (#u59db0d86-5327-55b2-a880-7d5f28b5b6ba)

‘Whatever is the matter, love?’ I asked, going up to her as Paula closed the front door.

‘My mother wouldn’t let me see my brothers and sisters,’ Zeena sobbed. ‘They were there, but she wouldn’t let me near them.’

‘Oh, love. Why not? And you’ve come all the way home on the bus in tears?’ I said, very concerned and taking her arm. ‘You should have phoned me and I could have collected you.’

‘I was too upset,’ she said. ‘I wasn’t thinking straight.’ Her eyes were red and her face was blotchy from crying.

‘All right, calm yourself. Let’s go and sit down and you can tell me what happened.’

Leaving the laundry bag in the hall, Zeena slipped off her shoes and headscarf and came with me into the living room, where we sat side by side on the sofa.

‘Do you need me, Mum?’ Paula asked, worried, having followed us in.

‘No, love. We’ll be all right. You get on with what you have to do. Perhaps you could fetch Zeena a glass of water.’

‘Sure.’

I passed Zeena the box of tissues and, taking one, she wiped her eyes. Paula returned with the glass of water and placed it on the coffee table.

‘Thank you,’ Zeena said quietly, and took a sip.

Paula went to the front room and I waited while Zeena drank a little water and then placed the glass on the table, wiping her eyes again.

‘What happened, love?’ I asked gently.

‘I went home and rang the doorbell,’ she said, with a small sob. ‘Mum took a long time to answer. As I waited I could hear my little brothers and sisters in the hall calling my name. They sounded so excited to be seeing me. I couldn’t wait to see them too. But then it all went quiet and I couldn’t hear them. When Mum answered the door she was very angry. She pulled me inside and began calling me horrible names. She told me to get my things quickly and never set foot in the house again.’

Zeena took a breath before continuing. ‘I went upstairs, but I couldn’t see my brothers and sisters anywhere. Usually they’re all over the house, running and playing, but there was no sign of them. Then I heard their voices coming from the front bedroom. The door was shut and I tried to open it, but it was locked. Mum had locked them in and had the key. She’d stayed downstairs and I called down to her and asked her why they were shut in the bedroom. She said it was to keep them safe from me. She said if they got close they might catch my evil.’ Zeena began crying again and I put my arm around her and held her close until she was calm enough to continue.

‘I spoke to them through the bedroom door,’ she said. ‘They thought it was a game to begin with and were laughing, but when the little ones realized they couldn’t get out and see me they started crying. Mum heard and yelled that I had five minutes to get my things and get out of the house or she’d call my father. I grabbed what I could from the bedroom and fled the house. I know I might never see my brothers and sisters again,’ she cried. ‘I have no family. My parents have disowned me. I should have stayed quiet and not said anything.’

Her tears fell and I held her hand. And again I thought what could she have done that was so horrendous for her mother to call her evil and stop her from seeing her little brothers and sisters? But now wasn’t the right time to ask; she was too upset. I comforted her and tried to offer some reassurance. ‘Zeena, I’ve been fostering for a very long time,’ I said. ‘In my experience, parents are often angry when their child or children first go into care. They can say hurtful things that they later regret. I think if you allow your mother time, she may feel differently. Your brothers and sisters will be missing you; they’re bound to ask for you.’

‘You don’t understand,’ she said. ‘In my family everyone does as my father says. If he tells my mother that I am evil and my brothers and sisters mustn’t have anything to do with me, then that’s that.’

‘Let’s wait and see,’ I said, feeling that perhaps Zeena was so upset that she was overstating the situation. ‘But we do need to tell Tara what’s happened. When she visits your parents she can talk to them. Social workers are used to dealing with difficult family matters. I’m sure she’ll know what to say so you can see your family.’

She shrugged despondently. ‘I suppose it’s worth a try,’ she said. ‘Shall I phone her now?’

‘If you wish, or I can?’

‘I’ll tell her,’ Zeena said.

‘If her voicemail is on, leave a message and ask her to call back,’ I said.

At Zeena’s age and with her level of maturity she could reasonably telephone her social worker if she wished. When younger children or those with learning difficulties were in foster care then it was usually the carer who made the telephone calls. However, as Zeena took another tissue from the box and blew her nose the landline rang. Paula, aware I was busy with Zeena, answered it in the hall.

‘Mum, it’s for you,’ she called.

‘Who is it?’ I asked.

‘A police lady.’

‘Thank you. I’ll take it in here.’

Zeena looked at me anxiously as I picked up the handset on the corner table.

‘It’s nothing to worry about,’ I said. ‘It’ll be the child protection officer – Tara said she would phone.’ Then I said into the receiver, ‘Hello, Cathy speaking.’

‘Hello, Cathy. It’s DI Norma Jones, child protection. I believe you have Zeena P— staying with you.’

‘Yes. She’s with me now.’

‘Can I speak to her, please?’

‘Yes, of course.’

I held the phone out to Zeena, but she shook her head and looked even more worried. ‘You talk to her, please,’ she said quietly.

I returned the phone to my ear. ‘She’s a bit upset at present,’ I said. ‘Can I give her a message?’

‘I need to make an appointment to see her as soon as possible. Can I visit you tomorrow after school? About five o’clock?’

‘Yes. That’s fine,’ I said. ‘Just a moment.’ I looked at Zeena, who was now mouthing something.

‘What, love?’ I asked her.

‘Is she Asian?’ Zeena whispered.

I can’t ask that, I thought, but then given Zeena’s concerns about the Asian network I thought I had to. ‘Sorry,’ I said, ‘but Zeena wants to know if you’re Asian?’

‘No. I’m white British,’ she said, easily. ‘Please tell her there is nothing to worry about and I’m aware of her concerns. But I will need to interview her about the allegations she’s made.’

I repeated this to Zeena and she gave a small, anxious nod.

‘All right,’ I said. ‘We’ll see you tomorrow, at five. You’ve got my address?’

‘Yes, and Zeena has my mobile number. Tell her to phone me if she’s worried at all.’

‘I will,’ I said.