The Grand Tour: Letters and photographs from the British Empire Expedition 1922

Agatha Christie

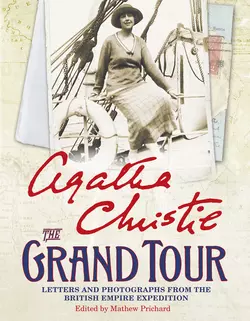

Unpublished for 90 years, Agatha Christie’s extensive and evocative letters and photographs from her year-long round-the-world trip to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and America as part of the British trade mission for the famous 1924 Empire Exhibition.In 1922 Agatha Christie set sail on a 10-month voyage around the British Empire with her husband as part of a trade mission to promote the forthcoming British Empire Exhibition. Leaving her two-year-old daughter behind with her sister, Agatha set sail at the end of January and did not return until December, but she kept up a detailed weekly correspondence with her mother, describing in detail the exotic places and people she encountered as the mission travelled through South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii and Canada.The extensive and previously unpublished letters are accompanied by hundreds of photos taken on her portable camera as well as some of the original letters, postcards, newspaper cuttings and memorabilia collected by Agatha on her trip.Edited and introduced by Agatha Christie’s grandson, Mathew Prichard, this unique travelogue reveals a new side to Agatha Christie, demonstrating how her appetite for exotic plots and locations for her books began with this eye-opening trip, which took place just after only her second novel had been published (the first leg of the tour to South Africa is very clearly the inspiration for the book she wrote immediately afterwards, The Man in the Brown Suit). The letters are full of tales of seasickness and sunburn, motor trips and surf boarding, and encounters with welcoming locals and overbearing Colonials.The Grand Tour is a book steeped in history, sure to fascinate anyone interested in the lost world of the 1920s. Coming from the pen of Britain’s biggest literary export and the world’s most widely translated author, it is also a fitting tribute to Agatha Christie and is sure to fascinate her legions of worldwide fans.

THE GRAND TOUR

Around the World with the Queen of Mystery

AGATHA CHRISTIE

Edited by Mathew Prichard

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_c087d2ff-3999-5fb0-8877-cb75d7a7d70c)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2012

THE GRAND TOUR. Copyright © 2012 by Christie Archive Trust. Excerpts from AGATHA CHRISTIE ™ An Autobiography copyright © 1977 by Agatha Christie Limited. Introduction and epilogue copyright © 2012 by Mathew Prichard.

Illustrations courtesy of the Christie Archive Trust.

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Source ISBN 978-0-00-744768-8

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2012 ISBN: 9780007460694

Version: 2017-04-13

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

CONTENTS

Cover (#ub42228cc-8453-57ae-bb2e-d1e4c8d1999c)

Title Page (#u98a81d6f-7dc3-5e13-a8ad-0f68f4e4399e)

Copyright (#ulink_d18703ee-97b4-5233-85da-393103f185ca)

Introduction (#ulink_42555f34-e8c7-549a-a572-10760a67273b)

Preface (#ulink_03628e59-591d-571c-acf0-536f82e09a2e)

Setting Off (#ulink_dc1f5a11-c04a-53f4-89d9-12e531c8827c)

South Africa (#ulink_39a2a6af-0405-54c0-9333-353e313ea5e8)

Australia (#litres_trial_promo)

New Zealand (#litres_trial_promo)

Honolulu (#litres_trial_promo)

Canada (#litres_trial_promo)

The Journey Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Chronology (#litres_trial_promo)

British Empire Exhibition (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

The Agatha Christie Collection (#litres_trial_promo)

Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_6e7a7e29-0571-589b-be92-1ec3724149ae)

by Mathew Prichard

By an extraordinary coincidence, it is 20 January 2012 when I sit down to begin writing the introduction to my grandparents’ participation in the British Empire Exhibition Mission, known as the Grand Tour, which my grandmother, Agatha Christie, brought so vividly to life in the letters and photographs she sent back to her family. The tour left on 20 January 1922, exactly 90 years ago today.

I called my grandmother Nima, presumably a first childish attempt at ‘Grandma’, and through force of habit I will use this family name in this piece, although of course the events she chronicled took place many years before I was born!

We have to be grateful that these wonderful letters have survived at all. It has been a continual frustration to me, in browsing through family memorabilia, that there are quite a few lovely letters from well-known (and not so well-known) people to Nima, but far fewer of her own letters, which by definition are in the hands of the people to whom she wrote. Fortunately in this case, however, her mother, to whom she wrote the most frequently, did keep the letters; when she sadly died three or four years later, presumably Nima reclaimed them, for they have survived with the rest of the material left by what was, I can promise you, a prolific letter-writing family! As you will see, it was a marvellous bonus to read all the letters for the first time a year or two ago, to see the brief addresses, and to leaf through the old black-and-white photographs, painstakingly pasted into a couple of old photograph albums.

It goes without saying that the world we live in has changed out of all recognition in those 90 years – some would say particularly the places visited on the Empire Tour: South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Canada. Not only have the countries changed, but the way we communicate, the way we do business, the way we behave as families – indeed the whole social environment in which people like my grandparents existed has changed so much that it is almost unrecognizable. I think some of the circumstances surrounding the Tour and the people involved would probably have been regarded as fairly eccentric even by their contemporaries, but even so, I think the changes are still very remarkable.

For instance, apart from my grandparents, the chief character concerned, one Major E. A. Belcher, whose last job before initiating this tour was Controller of the Supplies of Potatoes, was obviously a seriously eccentric and difficult man, whose unpredictability and inefficiency sorely tried my grandparents throughout the whole tour. One suspects that his friend and colleagues must have breathed a sigh of relief when they heard that he planned to be out of the country for 10 months! Certainly, however, somebody retained some confidence in him, for the expenses of the trip were considerable – four to seven people’s upkeep for 10 months (minus a month’s holiday for my grandparents), ‘free’ passage on ships all the way round the world, ‘free’ internal travel in each of the countries, not to mention the fees paid to Belcher and my grandfather Archie. At the end of this book I have recorded some evidence about the 1924 British Empire Exhibition. But at the end of the day, who are we to complain – we have gained a charming, perceptive and unconsciously revealing document concerning life shortly after the First World War, written by an author whose gift for storytelling remains second to none from that time to this.

It is worth dwelling for a while on communication. The only methods of communication used by members of the Tour appear to be letters or the occasional necessarily brief telegram. Not only no emails, but no telephones – in other words no immediate form of communication which, for instance, Nima could use to be reassured about the well-being of her two-year-old daughter Rosalind. Letters had to travel by the same means as the tour – by ship! And it appears that in either direction they took weeks or months to arrive, although within its own limitations the system worked very well. Even locally, communications were difficult, which made the keeping of itineraries and timetables challenging, to say the least. Worse, the difficulties of long-distance communication meant Nima and Archie knew before they set out that they would in essence be completely separated from their daughter for 10 months.

From a family point of view Nima and Archie’s decision to accompany Belcher on the Grand Tour was brave considering their precarious financial position at the time. I suspect their decision to go arose from Archie’s restlessness and dissatisfaction with his current job (a position which might not be kept open for his return); coupled with Nima’s passionate desire to see the world, and her suspicion that marriage to a businessman with two weeks’ holiday a year would make further opportunities for such adventures non-existent. Sitting at my desk, and reviewing in my mind Nima’s life-long love of travel, which took her at various times to the Middle East, North Africa, Sri Lanka, America, the West Indies – sometimes with her family in tow – it is hard to remember that forward vision was not available to her in 1922. She could not see her life spreading out before her, and who are we to blame such a passionate and enthusiastic person for taking what she thought was her one and only chance to see the far end of the world, whatever the financial risks and despite the certainty that she would miss her daughter dreadfully. It is also true to say that ‘family support systems’, including in Nima’s case, a mother, a sister and servants, were much more available and accepted than they are now.

So, Nima and Archie set off and what follows in this book is a completely spontaneous outpouring of wonder at the different people, scenery and events that unfolded before them as they went. Some of what they saw, such as the Victoria Falls, Table Mountain and Sydney Harbour, are still there, though much developed. Much more poignant to me (for I have visited all three cities) were the pictures of Hobart, Wellington, and particularly Cathedral Square in Christchurch, New Zealand. The first two are completely unrecognizable from the buzzing cities you see today. A simple black-and-white picture overwhelms me with a powerful sense of natural elegance and beauty, and, I confess, with a sense of guilt and regret that progress has meant the destruction of some thing so intrinsically valuable. Christchurch, of course, suffered a devastating earthquake in 2011, but I suspect that if a 1922 resident could see how the city has developed over the intervening decades, he or she would mourn the urban developments almost as poignantly.

One episode which particularly impressed me was Nima’s trip to Coochin Coochin Station to visit the Bells, who (as she said) seemed to own most of the cattle in Australia. With their natural vivacity and energy, the Bells provided a stark contrast to the inhibiting nature of Belcher’s company; but is it entirely my imagination that the freedom, spontaneity and independence displayed by the Bells on their own patch was something that Nima had never experienced before? I suspect, in good times and in bad, she never forgot it. I remember, in the 1950s, meeting Guilford Bell, Frick’s son, who ended up being one of the most innovative and successful architects in Australia, designing some iconic buildings on Sydney Harbour and in Melbourne. I remember him leaving after a weekend with us all and writing in the visitor’s book at Greenway, which desperately needed a lick of paint at the time, ‘Always paint me white!’ I also remember visiting him for dinner in his disarmingly simple (white) house in Melbourne, in which he had decreed that only one picture should be on display in each room. No matter, in the Living Room was one of the most charismatic and glowering landscapes I have ever seen, painted by Russell Drysdale as a gift to Guilford, who had designed a house for him. The Bells, all of them, were an inspiration to Nima. No wonder.

What is one to say about Nima’s photography? Ignoring the basic quality of her equipment (she had her camera stolen in South Africa – in my opinion the replacement was better) – it manages to be amazingly evocative. In browsing through the two albums she left us, I couldn’t help but admire her assiduousness: the camera must never have left her side. Perhaps this is also a figment of my imagination but I found myself thinking that her photography was like her writing in a different medium – spontaneous, direct, but occasionally with a shaft of brilliant artistic talent. The following is a list of subjects which she photographed that particularly impressed me – all quite different yet each evocative in its own way of the time and place it happened: logging in Canada, surfing in Honolulu, the police in Suva, the youngest cotton picker, trains, Susan in Coochin Coochin, and the ‘Bush train’. I will give you no further details – you will enjoy finding them for yourselves.

You would not be surprised to hear that the question I am most often asked about Nima is, ‘Yes, but what was she really like?’ I have spent, over the past month or so, some time reading these letters and looking at these photographs, and asking myself whether, in the light of what they reveal, my standard answers need to be reviewed. My standard answers were that she was a shy, reserved person, who was very reluctant to talk in public, give press interviews, discuss her work or otherwise engage in activity other than writing books. She was never happier than being with her family or close friends; she was a devout person who believed in God (and in evil) and, to me, an inspirational grandmother far more interested in my own likes and dislikes than in promoting or discussing herself. She was, I have always said, the best listener I ever met. I still believe, based on the evidence of the 25 years or so that I knew her well, that all this is true.

But, as I read her account of the Grand Tour, I see glimpses of another Agatha Christie. One with far more confidence in herself publicly than the one I remember. One who sang in public in Coochin Coochin, was very sociable on board ship, and who had the courage to make the decision to go on the tour and leave her daughter for 10 months. A person who, even though it turned out to be the wrong thing to do, took her place directly beside local dignitaries at the lunch table until being told to go back and sit next to her husband. A young woman of 32 who was actually confident in herself, and in her husband, amid constantly changing circumstances and for the most part in the company of total strangers. One suspects, indeed, that Nima and Archie were the glue that held the tour together, particularly in view of Belcher’s unpredictable nature. So I find myself in the presence of a younger Agatha, more confident and assertive than the Nima that I remember – and what do I feel? I feel even more proud of her.

Some three to four years after returning from the tour, as all the world seems to know, Nima had to suffer the death of her mother, and separation and divorce from Archie. As a consequence of these traumatic experiences, she famously got lost, or disappeared, eventually to reappear in Harrogate under another name. It is not appropriate to discuss here the details of this experience, except to say that for most of us the juxtaposition of two of the most disturbing events that can happen to anyone would be life-changing. I am sure Nima was no exception and that a very important part of the confident, carefree wife who accompanied Archie in 1922 was lost forever after the events of1926–27. Fromthenon, despite a very successful second marriage, all her confidence, energy and genius were concentrated on supporting her new husband and, of course, on her work. The days of vivacious Agatha at public gatherings were not to return; but perhaps in the end we were all the benefactors, for in both quantity and quality her work after 1927 was amazing.

From a historical point of view the account of the Grand Tour, both literary and photographic, is a remarkable snapshot of life in the 1920s, nostalgic and curious. For me it is also a glorious vision of a grandmother I never knew, but who I am very glad existed.

I always think that anybody who ventures to write about Agatha Christie should not bypass her work, and Nima would have agreed. I therefore have to tell you that shortly after the British Empire Mission returned home, Nima published The Man in the Brown Suit, an adventure story; and unusually for her, she included a direct portrayal of a real acquaintance – an impersonation of Belcher called Sir Eustace Pedler. Until Belcher objected, he was going to be murdered, but Nima gave him a title (‘he will like that,’ said Archie). As I never reveal the plots of Nima’s stories, all I will say beyond that is that Sir Eustace plays a prominent role! Nima very rarely used real individuals as the basis for her characters, indeed I’m not sure this wasn’t the only instance; and she didn’t really think it worked. Thus, however, were the many varied characters and events of the Grand Tour given fictional representation. Interestingly, there are those who think that Anne Beddingfield has a marked resemblance to the young and adventurous Agatha too…

Finally, I have tried to interfere with the flow and content of the letters as little as possible. We should all remember that the letters were written 90 years ago in a different social era, and inevitably there is also some repetition, as well as occasional inconsistencies in grammar and punctuation. Many of the captions to the photographs are Nima’s own own from her albums.

MATHEW PRICHARD

20 January 2012

PREFACE (#ulink_471ed8ad-080d-5120-96b7-dc2ccc94c5ab)

I had written three books, was happily married, and my heart’s desire was to live in the country.

Both Archie and Patrick Spence – a friend of ours who also worked at Goldstein’s – were getting rather pessimistic about their jobs: the prospects as promised or hinted at did not seem tomaterialise. They were given certain directorships, butthe director ships were always of hazardous companies – sometimes on the brink of bankruptcy. Spence once said, ‘I think these people are a lot of ruddy crooks. All quite legal, you know. Still, I don’t like it, do you?’

Archie said that he thought that some of it was not very reputable. ‘I rather wish,’ he said thoughtfully, ‘I could make a change.’ He liked City life and had an aptitude for it, but as time went on he was less and less keen on his employers.

And then something completely unforeseen came up.

Archie had a friend who had been a master at Clifton – a Major Belcher. Major Belcher was a character. He was a man with terrific powers of bluff. He had, according to his own story, bluffed himself into the position of Controller of Potatoes during the war. How much of Belcher’s stories was invented and how much true, we never knew, but anyway he made a good story of this one. He had been a man of forty or fifty odd when the war broke out, and though he was offered a stay-at-home job in the War Office he did not care for it much. Anyway, when dining with a V.I.P. one night, the conversation fell on potatoes, which were really a great problem in the 1914–18 war. As far as I can remember, they vanished quite soon. At the hospital, I know, we never had them. Whether the shortage was entirely due to Belcher’s control of them I don’t know, but I should not be surprised to hear it.

‘This pompous old fool who was talking to me,’ said Belcher, ‘said the potato position was going to be serious, very serious indeed. I told him that something had to be done about it – too many people messing about. Somebody had got to take the whole thing over – one man to take control. Well, he agreed with me. “But mind you,”’ I said, “he’d have to be paid pretty highly. No good giving a mingy salary to a man and expecting to get one who’s any good – you’ve got to have someone who’s the tops. You ought to give him at least—”’ and here he mentioned a sum of several thousands of pounds. ‘That’s very high,’ said the V.I.P. ‘You’ve got to get a good man,’ said Belcher. ‘Mind you, if you offered it to me, I wouldn’t take it on myself, at that price.’

That was the operative sentence. A few days later Belcher was begged, on his own valuation, to accept such a sum, and control potatoes.

‘What did you know about potatoes?’ I asked him.

‘I didn’t know a thing,’ said Belcher. ‘But I wasn’t going to let on. I mean, you can do anything – you’ve only got to get a man as second-in-command who knows a bit about it, and read it up a bit, and there you are!’ He was a man with a wonderful capacity for impressing people. He had a great belief in his own powers of organisation – and it was sometimes a long time before anyone found out the havoc he was causing. The truth is that there never was a man less able to organise. His idea, like that of many politicians, was first to disrupt the entire industry, or whatever it might be, and having thrown it into chaos, to reassemble it, as Omar Khayyam might have said, ‘nearer to the heart’s desire’. The trouble was that, when it came to reorganising, Belcher was no good. But people seldom discovered that until too late.

At some period of his career he went to New Zealand, where he so impressed the governors of a school with his plans for reorganisation that they rushed to engage him as headmaster. About a year later he was offered an enormous sum of money to give up the job – not because of any disgraceful conduct, but solely because of the muddle he had introduced, the hatred which he aroused in others, and his own pleasure in what he called ‘a forward-looking, up-to-date, progressive administration’. As I say, he was a character. Sometimes you hated him, sometimes you were quite fond of him.

Belcher came to dinner with us one night, being out of the potato job, and explained what he was about to do next. ‘You know this Empire Exhibition we’re having in eighteen months’ time? Well, the thing has got to be properly organised. The Dominions have got to be alerted, to stand on their toes and to co-operate in the whole thing. I’m going on a mission – the British Empire Mission – going round the world, starting in January.’ He went on to detail his schemes. ‘What I want,’ he said, ‘is someone to come with me as financial adviser. What about you, Archie? You’ve always had a good head on your shoulders. You were Head of the School at Clift on, you’ve had all this experience in the City. You’re just the man I want.’

‘I couldn’t leave my job,’ said Archie.

‘Why not? Put it to your boss properly – point out it will widen your experience and all that. He’ll keep the job open for you, I expect.’

Archie said he doubted if Mr Goldstein would do anything of the kind.

‘Well, think it over, my boy. I’d like to have you. Agatha could come too, of course. She likes travelling, doesn’t she?’

‘Yes,’ I said – a monosyllable of understatement.

‘I’ll tell you what the itinerary is. We go first to South Africa. You and me, and a secretary, of course. With us would be going the Hyams. I don’t know if you know Hyam – he’s a potato king from East Anglia. A very sound fellow. He’s a great friend of mine. He’d bring his wife and daughter. They’d only go as far as South Africa. Hyam can’t afford to come further because he has got too many business deals on here. After that we push on to Australia; and after Australia New Zealand. I’m going to take a bit of time off in New Zealand – I’ve got a lot of friends out there; I like the country. We’d have, perhaps, a month’s holiday. You could go on to Hawaii, if you liked, Honolulu.’

‘Honolulu,’ I breathed. It sounded like the kind of phantasy you had in dreams.

‘Then on to Canada, and so home. It would take about nine to ten months. What about it?’

We realised at last that he really meant it. We went into the thing fairly carefully. Archie’s expenses would, of course, all be paid, and outside that he would be offered a fee of £1000. If I accompanied the party practically all my travelling costs would be paid, since I would accompany Archie as his wife, and free transport was being given on ships and on the national railways of the various countries.

We worked furiously over finances. It seemed, on the whole, that it could be done. Archie’s £1000 ought to cover my expenses in hotels, and a month’s holiday for both of us in Honolulu. It would be a near thing, but we thought it was just possible.

Archie and I had twice gone abroad for a short holiday: once to the south of France, to the Pyrenees, and once to Switzerland. We both loved travelling – I had certainly been given a taste for it by that early experience when I was seven years old. Anyway, I longed to see the world, and it seemed to me highly probable that I never should. We were now committed to the business life, and a business man, as far as I could see, never got more than a fortnight’s holiday a year. A fortnight would not take you far. I longed to see China and Japan and India and Hawaii, and a great many other places, but my dream remained, and probably always would remain, wishful thinking.

‘It’s a risk,’ I said. ‘A terrible risk.’

‘Yes, it’s a risk. I realise we shall probably land up back in England without a penny, with a little over a hundred a year between us, and nothing else; that jobs will be hard to get – probably even harder than now. On the other hand, well – if you don’t take a risk you never get anywhere, do you?’

‘It’s rather up to you,’ Archie said. ‘What shall we do about Teddy?’ Teddy was our name for Rosalind at that time – I think because we had once called her in fun The Tadpole.

‘Punkie’ – the name we all used for Madge now – would take Teddy. Or mother – they would be delighted. And she’s got Nurse. Yes – yes – that part of it is all right. It’s the only chance we shall ever have, I said wistfully.

We thought about it, and thought about it.

‘Of course – you could go,’ I said, bracing myself to be unselfish, ‘and I stay behind.’

I looked at him. He looked at me.

‘I’m not going to leave you behind,’ he said. ‘I wouldn’t enjoy it if I did that. No, either you risk it and come too, or not – but it’s up to you, because you risk more than I do, really.’

So again we sat and thought, and I adopted Archie’s point of view.

‘I think you’re right,’ I said. ‘It’s our chance. If we don’t do it we shall always be mad with ourselves. No, as you say, if you can’t take the risk of doing something you want, when the chance comes, life isn’t worth living.’

We had never been people who played safe. We had persisted in marrying against all opposition, and now we were determined to see the world and risk what would happen on our return.

Our home arrangements were not difficult. The Addison Mansions flat could be let advantageously, and that would pay Jessie’s wages. My mother and my sister were delighted to have Rosalind and Nurse. The only opposition of any kind came at the last moment, when we learnt that my brother Monty was coming home on leave from Africa. My sister was outraged that I was not going to stay in England for his visit.

‘Your only brother, coming back after being wounded in the war, and having been away for years, and you choose to go off round the world at that moment. I think it’s disgraceful. You ought to put your brother first.’

‘Well, I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘I ought to put my husband first. He is going on this trip and I’m going with him. Wives should go with their husbands.’

‘Monty’s your only brother, and it’s your only chance of seeing him, perhaps for years more.’

She quite upset me in the end; but my mother was strongly on my side. ‘A wife’s duty is to go with her husband,’ she said. ‘A husband must come first, even before your children – and a brother is further away still. Remember, if you’re not with your husband, if you leave him too much, you’ll lose him. That’s specially true of a man like Archie.’

‘I’m sure that’s not so,’ I said indignantly. ‘Archie is the most faithful person in the world.’

‘You never know with any man,’ said my mother, speaking in a true Victorian spirit. ‘A wife ought to be with her husband – and if she isn’t, then he feels he has a right to forget her.’

AGATHA CHRISTIE

from An Autobiography

SETTING OFF (#ulink_c087d2ff-3999-5fb0-8877-cb75d7a7d70c)

Going round the world was one of the most exciting things that ever happened to me. It was so exciting that I could not believe it was true. I kept repeating to myself, ‘I am going round the world.’ The highlight, of course, was the thought of our holiday in Honolulu. That I should go to a South Sea island was beyond my wildest dream. It is hard for anyone to realise how one felt then, only knowing what happens nowadays. Cruises, and tours abroad, are a matter of course. They are arranged reasonably cheaply, and almost anyone appears to be able to manage one in the end.

When Archie and I had gone to stay in the Pyrenees, we had travelled second-class, sitting up all night. (Third class on foreign railways was considered to be much the same as steerage on a boat. Indeed, even in England, ladies travelling alone would never have travelled third class. Bugs, lice, and drunken men were the least to be expected if you did so, according to Grannie. Even ladies’ maids always travelled second.) We had walked from place to place in the Pyrenees and stayed at cheap hotels. We doubted afterwards whether we would be able to afford it the following year.

The first newspaper cutting from Agatha’s photo album. The Times caption mistakes Miss Hiam for Mrs Christie.

Now there loomed before us a luxury tour indeed. Belcher, naturally, had arranged to do everything in first-class style. Nothing but the best was good enough for the British Empire Exhibition Mission. We were what would be termed nowadays V.I.P.s, one and all.

Mr Bates, Belcher’s secretary, was a serious and credulous young man. He was an excellent secretary, but had the appearance of a villain in a melodrama, with black hair, flashing eyes and an altogether sinister aspect.

‘Looks the complete thug, doesn’t he?’ said Belcher. ‘You’d say he was going to cut your throat any moment. Actually he is the most respectable fellow you have ever known.’

Before we reached Cape Town we wondered how on earth Bates could stand being Belcher’s secretary. He was unceasingly bullied, made to work at any hour of the day or night Belcher felt like it, and developed films, took dictation, wrote and re-wrote the letters that Belcher altered the whole time. I presume he got a good salary – nothing else would have made it worth while, I am sure, especially since he had no particular love of travel. Indeed he was highly nervous in foreign parts – mainly about snakes, which he was convinced we would encounter in large quantities in every country we went to. They would be waiting particularly to attack him.

Although we started out in such high spirits, my enjoyment at least was immediately cut short. The weather was atrocious. On board the Kildonan Castle everything seemed perfect until the sea took charge. The Bay of Biscay was at its worst. I lay in my cabin groaning with sea-sickness. For four days I was prostrate, unable to keep a thing down. In the end Archie got the ship’s doctor to have a look at me. I don’t think the doctor had ever taken sea-sickness seriously. He gave me something which ‘might quieten things down,’ he said, but as it came up as soon as it got inside my stomach it was unable to do me much good. I continued to groan and feel like death, and indeed look like death; for a woman in a cabin not far from mine, having caught a few glimpses of me through the open door, asked the stewardess with great interest: ‘Is the lady in the cabin opposite dead yet?’ I spoke seriously to Archie one evening. ‘When we get to Madeira,’ I said, ‘if I am still alive, I am going to get off this boat.’

‘Oh I expect you’ll feel better soon.’

‘No, I shall never feel better. I must get offthis boat. I must get on dry land.’

‘You’ll still have to get back to England,’ he pointed out, ‘even if you did get off in Madeira.’

‘I needn’t,’ I said, ‘I could stay there. I could do some work there.’

‘What work?’ asked Archie, disbelievingly.

It was true that in those days employment for women was in short supply. Women were daughters to be supported, or wives to be supported, or widows to exist on what their husbands had left or their relations could provide. They could be companions to old ladies, or they could go as nursery governesses to children. However, I had an answer to that objection. ‘I could be a parlour-maid,’ I said. ‘I would quite like to be a parlour-maid.’

Parlour-maids were always needed, especially if they were tall. A tall parlour-maid never had any difficulty in finding a jobs – read that delightful book of Margery Sharp’s, Cluny Brown – and I was quite sure that I was well enough qualified. I knew what wine glasses to put on the table. I could open and shut the front door. I could clean the silver – we always cleaned our own silver photograph frames and bric-à-brac at home – and I could wait at table reasonably well. ‘Yes,’ I said faintly, ‘I could be a parlour-maid.’

‘Well, we’ll see,’ said Archie, ‘when we get to Madeira.’

However, by the time we arrived I was so weak that I couldn’t even contemplate getting off the bed. In fact I now felt that the only solution was to remain on the boat and die within the next day or two. After the boat had been in Madeira about five or six hours, however, I suddenly felt a good deal better. The next morning out from Madeira dawned bright and sunny, and the sea was calm. I wondered, as one does with sea-sickness, what on earth I had been making such a fuss about. After all, there was nothing the matter with me really, I had just been sea-sick.

There is no gap in the world as complete as that between one who is sea-sick and one who is not. Neither can understand the state of the other. I was never really to get my sea-legs. Everyone always assured me that after you got through the first few days you were all right. It was not true. Whenever it was rough again I felt ill, particularly if the boat pitched – but since on our cruise it was mostly fair weather, I had a happy time.

Agatha on board the Kildonan Castle.

The R.M.S Kildonan Castle sailed via Madeira for Capetown, Angola, East London and Natal from Southampton on the 20th January 1922.

UNION-CASTLE LINE R.M.S ‘KILDONAN CASTLE’

First day: 20 January 1922

Darling mummy

Everything very comfortable – nice cabin with lots of room. I do love my violets. Take care of yourself, darling – I do love you so much.

Will write again from Madeira.

Your loving

Agatha

R.M.S KILDONAN CASTLE

[undated]

Darling Mummy,

I couldn’t send you an amusing and cheerful letter from Madeira because I was laid low, and nearly dead! I was terribly ill – it was very rough and everyone was ill. Archie, Belcher, and Hiam were all right, of course but ‘the ladies’ and Mr Bates were very sorry for themselves. I was quite determined to get off at Madeira and come straight home, or take a Villa there for the winter. The day before we got there, I was very bad. Sick without ceasing, having tried everything from champagne and brandy to dry biscuits and pickles, and my arms and legs were all going pins and needly and dead, so Archie fetched the doctor along, and he gave me teaspoonful doses of something or other, chloroform stuff, which stopped the sickness, and nothing to eat for twenty four hours, and then Brand’s beef essence. When we got to Madeira, Archie got me up on deck, and fed me with it, whilst I almost wept because Madeira looked so beautiful! I’d no idea of it. It looked like Kinderscout put bang on the sea, green hills and ravines with houses perched on them like Upper House, or rather like Dartmouth. It was grey weather too, so it must look even more beautiful in sunshine. I couldn’t go ashore of course, which was rather disappointing.

But since then, I’ve been quite all right, and am now enjoying myself hugely, feel perfectly well, have baths and meals, and get up in the morning just as though it was dry land.

From henceforth I shall write you a kind of diary, a little every day. I need hardly say that Belcher was at once made chairman of the Sports Committee on board. The boat is not very full. There is rather a nice sailor lad called Ashby going out to join a ship at Cape Town, who went with Mrs Tweedale over the haunted house in Torquay, a delightful woman, Miss Wright, belonging to some college out in South Africa who is most amusing, a Miss Gold who is the thinnest girl I have ever seen and like a Botticelli Madonna, and a particularly fat fellow called Samels with a very nice wife and kiddies. He’s a great ostrich person, and the Mission is fixing up a meeting with him out there. We have trained the Chief Engineer, at whose table we sit, to drink ‘Success to the Mission’ every night, which he does, murmuring. ‘But I’m still not sure what kind of a mission it is. They say it’s not religious.’

‘Our Major Belcher.’

The Hiams are nice, but dull. Won’t do anything – enter for quoits or take part in things. Archie and I entered bravely for everything, had our first contest yesterday, when to our utter surprise, we knocked out two Belgians who have infuriated the ship by hanging on to the quoits and practising all day long. It was a most popular victory. Everyone kept coming up to us and saying ‘I hear you’ve knocked out the Dagoes! Splendid.’

Belcher gave us a screaming description of his visit to the King. Whilst airily chatting to Wigram on arrival, a super footman approached and murmured ‘which links would you wish to wear this evening sir?’ ‘Oh any links, any links,’ said Belcher, to which the footman hissed in an agitated whisper: ‘I can’t find any.’ ‘And then, of course, I had to take the brass ones out of the shirt I was wearing and hand them to him. Most unfortunate!’ The King was charming and most natural, and the Queen had a full description of all the ladies accompanying the Mission, and made a note of my book. Princess Mary was not at all a dump, but very jolly, but Lascelles was a dull dog, who said little, and drank champagne in enormous quantities! They talked a good deal about ‘their boy’. The Queen said ‘My boy has had thirty five wooden caskets presented to him when he was in Australia, and of course he doesn’t know what to do with them. Lovely wood, but hideously made.’ The King told a story of Hughes starting out to drive with the Prince through Sydney. ‘He started in a topper, but when they got to the suburbs, he hid it under the seat and produced a bowler, and by the time they got to the slums be was wearing a check cap!’ He spoke very warmly of Smuts, and said Belcher reminded him of Redmond, and that Ireland would not be in the state it was if Redmond had lived. Two braces of pheasants were presented to Belcher on leaving, and we ate them on board last night, served with great éclat and ceremony!

Agatha, and Archie in his tropical suit.

Aboard ship.

Captain Sir Benjamin Chave KBE (far left), Chief Officer Mr D. Nicoll and Chief Engineer Mr A. Munro.

Very hot now and lots of porpoises leaping, and I’ve just seen a flying fish! We passed the Grand Peak of Tenerife on Wednesday, and saw the Cape Verde lights last night. No more land now until Cape Town.

Saturday [February 4]

We had the children’s Sports today, and I was asked to give away the prizes, an honour procured for me by Belcher, as against the rival claims of Mrs Blake (wife of the Captain of the Queen Elizabeth) B. pointing out that I was of equal rank, being the wife of a Colonel in the Army, and had taken some interest in the Sports, Mrs Blake having taken none! She looks very amusing, spends all day talking to a long lean brown Commissioner for Nyasaland. I shall talk to her soon because I like the look of her.

Mrs Blake.

Mr Hiam and Mr Samels had a long and mysterious discussion on pigskin last night, H. declaring there was no such thing, S. saying there was, and that he would show him the skins, to which H. countered by saying ‘Ah, but can you show me a pig being skinned,’ and S. climbed down, and said he could not say more before the ladies. I had no idea pig skin was such a delicate subject. It seems to rank with bech de mer!

Mr Edge.

We’ve had several Bridge fours with Samels. It always takes a least three hours to finish a rubber, because he and Belcher never stop overcalling their hands, and doubling. On the whole Belcher pushes Samels a little further than Samels pushes Belcher! S. has promised me something very choice in ostrich feathers if we come to Port Elizabeth. I am now waiting for someone to ask me if I like diamonds or gold nuggets!

Mr Mayne.

Jack and Betty, the Aerial Sensation perform on the After Deck.

There are some Dutch people, the Fichardts, I believe she was a daughter of President Stein, and they are violently anti-English. Belcher spent a whole evening talking to them last night, and this morning is writing the result in his Diary, and sending an ‘Extract’ to the King! We are sending a wedding present to Princess Mary from South Africa, and he has promised the Queen an Album of photos of the Mission and its doings!

There is a Mr Edge on board, a rich elderly bachelor, who takes thousands of photos all day long. He has made nine voyages to the Cape and back, never lands – just likes the trip.

The great daily excitement, of course is the ‘sweep’ on the day’s run. 1/ tickets, and if you draw a number, it is most thrilling. I’ve drawn a number nearly every day. My one today was a good one, and sold in the Auction for a pound. Not fancying my luck, I’ve never bought one in so far, but let them go for what they’d fetch – luckily as it proves, but Archie bought his in yesterday for 25/ and got second – £5 15/! Belcher, by common acclamation, is always auctioneer, with Samels (in a terrible green and white striped shirt!) as clown of the piece, and there is a little American called Mayne who does most of the bidding. He is rather nice, dances beautifully, and deals in ‘grain elevators’ (as much of a mystery to me as ‘filled cheese’ was to you). We had a fancy dress dance last night, and he was very serious about his costume. ‘I have a costume, period 1840, and a costume, period 1830, and a costume 1820!’ In the end, the preference was given to the 1840. My Bacchante was quite a success, and Belcher hired a marvellous Chu Chin Chow costume from the Barber, suitable to his bulk, and looked simply screaming – in fact won 1st prize.

Agatha in her ‘Chariots and Horses’ outfit.

Mrs Blake and Mr Murray.

Of course it has been very hot the last few days, passing over the line [Equator]. I haven’t minded it. We’ve got a big electric fan in the cabin, and I wrested the top bunk from Archie, and we sleep with no clothes on, and trust to Providence to wake up in the morning before the steward comes in! But the heat nearly kills poor Mrs Hiam. It’s getting cooler again now.

With a lot of pushing, Sylvia Hiam is ‘getting off’ with young Ashby. He’s such a nice boy, and she’s the only young thing on the ship, but although very pretty, is a terrible mutt.

I have succeeded in talking to Mrs Blake, and find her most amusing. She dined at our table on the occasion of the last brace of the King’s pheasants! Mr Murray, the commissioner, is very nice too. She is going to the Mount Nelson Hotel also, to be about three weeks with her father, who lives out there for his lungs, I gather. She and I have taken rather a fancy to each other.

To our intense surprise, Archie and I succeeded in winning the 2nd prize for Deck Quoits – and very nearly won the 1st prize. We selected very nice table napkin rings with the Kildonan Castle Arms on them. At one moment, I rather fancied I might win the Ladies singles, but there came against me, Mrs Fichardt, who is quite my idea of the Mother of the Gracchi, a great big fair woman, very calm, with really rather a statuesque figure built on big lines, no nerves, and about fourteen children who cluster round and urge her on in eager Dutch.

SOUTH AFRICA (#ulink_fe6ea0a5-48dd-56db-893a-550bb6338fd7)

My memories of Cape Town are more vivid than of other places; I suppose because it was the first real port we came to, and it was all so new and strange. Table Mountain with its queer flat shape, the sunshine, the delicious peaches, the bathing – it was all wonderful. I have never been back there – really I cannot think why. I loved it so much. We stayed at one of the best hotels, where Belcher made himself felt from the beginning. He was infuriated with the fruit served for breakfast, which was hard and unripe. ‘What do you call these?’ he roared. ‘Peaches? You could bounce them and they wouldn’t come to any harm.’ He suited his action to the word, and bounced about five unripe peaches. ‘You see?’ he said. They don’t squash. They ought to squash if they were ripe.’

It was then that I got my inkling that travelling with Belcher might not be as pleasant as it had seemed in prospect at our dinner-table in the flat a month before.

This is no travel book – only a dwelling back on those memories that stand out in my mind; times that have mattered to me, places and incidents that have enchanted me. South Africa meant a lot to me. From Cape Town the party divided. Archie, Mrs Hyam, and Sylvia went to Port Elizabeth, and were to rejoin us in Rhodesia. Belcher, Mr Hyam and I went to the diamond mines at Kimberley, on through the Matopos, to rejoin the others at Salisbury. My memory brings back to me hot dusty days in the train going north through the Karroo, being ceaselessly thirsty, and having iced lemonades. I remember a long straight line of railway in Bechuanaland. Vague thoughts come back of Belcher bullying Bates and arguing with Hyam. The Matopos I found exciting, with their great boulders piled up as though a giant had thrown them there.

Group photo at Hout’s Bay, Cape Town.

At Salisbury we had a pleasant time among happy English people, and from there Archie and I went on a quick trip to the Victoria Falls. I am glad I have never been back, so that my first memory of them remains unaffected. Great trees, soft mists of rain, its rainbow colouring, wandering through the forest with Archie, and every now and then the rainbow mist parting to show you for one tantalising second the Falls in all their glory pouring down. Yes, I put that as one of my seven wonders of the world.

We went to Livingstone and saw the crocodiles swim ming about, and the hippopotami. From the train journey I brought back carved wooden animals, held up at various stations by little native boys, asking three pence or sixpence for them. They were delightful. I still have several of them, carved in soft wood and marked, I suppose, with a hot poker: elands, giraffes, hippopotami, zebras – simple, crude, and with a great charm and grace of their own.

We went to Johannesburg, of which I have no memory at all; to Pretoria, of which I remember the golden stone of the Union Buildings; then on to Durban, which was a disappointment because one had to bathe in an enclosure, netted off from the open sea. The thing I enjoyed most, I suppose, in Cape Province, was the bathing. Whenever we could steal time off – or rather when Archie could – we took the train and went to Muizenberg, got our surf boards, and went out surfing together. The surf boards in South Africa were made of light, thin wood, easy to carry, and one soon got the knack of coming in on the waves. It was occasionally painful as you took a nose dive down into the sand, but on the whole it was easy sport and great fun. We had picnics there, sitting in the sand dunes. I remember the beautiful flowers, especially, I think, at the Bishop’s house or Palace, where we must have been to a party. There was a red gar-den, and also a blue garden with tall blue flowers. The blue garden was particularly lovely with its background of plumbago.

Finances went well in South Africa, which cheered us up. We were the guests of the Government in practically every hotel, and we had free travel on the railways – so only our personal trip to the Victoria Falls involved us in serious expenses.

MOUNT NELSON HOTEL

February 6 [Monday]

We have arrived! Great excitement as to whether we should get in today or not. The Chief Engineer had us into his cabin after dinner, and handed round Van Dams(?) (liqueurs), drinking several himself, and then became most suspiciously loquacious for one so Scotch, lamenting the fact that the Kildonan should be late on her first voyage. Between a fine of £100 for every hour she is late after 6 am and the fear of what the Board will say if he uses too many hundred tons of coal, the poor man is torn asunder. He then spoke movingly against early marriages, and besought Sylvia not to contract one rashly. We thought he must have been unfortunate himself, but it turned out that he was devoted to his wife, but pitied her deeply for being married to him!

We ran into a fog in the afternoon, and stayed about hooting dismally, but at last it cleared and we got in about 7.30 – just in time to have a lovely view of Table Mountain in the setting sun. A representative of the Union Government came on board to meet us, also the Deputy Trade Commissioner, Major Featherston. He had cars waiting for us, and had arranged for our baggage to pass straight through the customs without being examined, and we came right up here. Comfortable rooms and bath, indifferent food, and no one ever answers the bell unless it is by accident but then they are quite kind.

Tuesday [February 7]

Very hot. I love it but the Hiams are nearly dead again. The Mountains all round make this place beautiful, and as you go down to the town, there are the most lovely flowers climbing up the houses, lots of mauvy blue ones, great morning glories and a kind of blue hawthorn hedge. The men had to go to a lunch so we went into the town to get films developed etc, and bought a 1/ basket of peaches, great yellow ones, five we thought, but discovered there were lots underneath and really about fifteen. We ate them juicily in the garden, and little Natal pineapples at 2d each. I had begun to think that places where fruit cost next to nothing only existed in books, but we have struck it here all right. We learnt afterwards that 15 peaches for a 1/ was an imposition, but I am still too fresh from London to be able to feel it! I do wish you could be here. We would have a lovely eat together! Darling Mummy, it would be nice.

The Mount Nelson Hotel.

In the afternoon, I met Archie at the station and we went to Muizenberg, and surf bathed with planks! Very difficult. We can’t do it a bit yet. But it was lovely there, with a bay of great mountains coming right down to the sea. I had no idea there were so many mountains. And the sea is really hot, the only sea I have ever known that you don’t shiver when you first put your toes in.

Poor Belcher had a very bad foot – blood poisoning – its been getting worse all the voyage because he won’t rest it. It keeps breaking out – rather like Archie’s did. I’m very sorry for him. We’re being taken on a motoring tour by prominent Manufacturers today. I do love this sunshine.

Agatha surfing at Muizenberg.

I sent you a cable and got yours about an hour after wards. It is nice to know all is going well. I will write to Mr Rotherham about buying me another Chinese Bond. I like them! Undoubtedly this is a lovely trip. The only serious thing is, there seems to be no boat running to Ceylon. They all go to Bombay. It will be terribly sad if we have to miss it out.

This letter is for all, so send it on to Punkie. Love to her and James, and my own darling little Pussy Cat, and love to dear old Mont, and lots to you, darling. I will send some post cards and snap shots by next mail. Am not quite at home on the little Corona yet, as you may note, but at any rate its better than my handwriting! Keep well, darling, I wish you were here.

Your loving

Agatha

Agatha and Ashby.

Sea Point.

MOUNT NELSON HOTEL CAPE TOWN

Wednesday February 8

We were treated to a long lecture by Belcher this morning. He began by saying that his doctor had expressly stated he was not to be thwarted or crossed in any way, that his blood pressure was abnormally high, and that any undue excitement would probably end fatally – which would be disastrous for the Mission, as no one else had a grain of administrative capacity. It was therefore absolutely necessary that the other board members of the Missions should do their bit with Featherston and shield their Chief. If they preferred to murder him instead, he fancied the thanks of the civilised world would be theirs!

Agatha in the pool at Sea Point.

Groote Scuur interior.

Mr Hiam spent the morning in the cold storage chambers, and came back with a solemn warning to us all never to eat any more meat whilst in South Africa! The fish here is uneatable anyway, and Belcher gave us a lurid description of what the natives do to the fruit – so it would seem that we must resign ourselves to slow starvation.

The Hiams went off to see some friends this afternoon. Quite a relief. Mrs H. is most kind and sweet, but a little stupid. It is really quite a puzzle sometimes to know how to go on talking to her.

Belcher took a car, and he and I and Archie drove out to Groote Scuur, Rhodes’s house, where Smuts lives when he is here, and we went all over it. Most attractive, with the big Dutch wardrobes and cupboards, and the teakwood panelling. The bathroom is rather famous, all marble, and the bath hewn out of a solid block of granite. But the bath is too black looking to be attractive. There is a wonderful slope of hydrangeas in the garden, but they are over now. We went on to the Rhodes Memorial, and then Belcher tried to photograph the lions, offering the keeper the following tariff:

For making the lion turn its head round – 1/

For going into the cage – 2/

For sitting on the lion’s back – 10/ (paid in advance)

The man replied with scorn that he looked after the birds and had nothing to do with the lions!

The Rhodes Memorial.

Archie on the Rhodes Memorial.

‘Physical Energy’, Rhodes Memorial.

Thursday [February 9]

Today is grey and cold. The Hiams rejoice, but I regret the heat. Sylvia, I, and the Naval Attaché (Ashby) went off to Muizenberg. High tide and shelving beach. I didn’t tilt my board up enough, and consequently it stuck in the sand, and jolted me violently in the middle! I at once loathed surfing! But recovered shortly. Ashby was rather good for a first attempt. Sylvia doesn’t bathe, in case she should get sticky! She snapped us both as we came out ‘resting on our boards’, and suddenly a perfectly strange young man bust up, raised his hat, said to me: ‘may I have the pleasure also?’ and before I could reply, ‘snapped’ me neatly, murmured ‘Many thanks’ and retreated again.

Archie came out after lunch, stayed in an hour, and got very angry, because he didn’t get one good run! It was awfully funny to watch him trying so hard, and wave after wave passing him by.

In the evening we went to the Town Hall, were received by the Mayor and Mrs Gardiner, and had a lovely concert which we heard from their box. The conductor, Wendt, is as good as anyone I have ever heard.

The faithful Featherston (whom Belcher persists in referring to as Wetherslab) returned with us. We were instructed in a fierce whisper to remain in the lounge, and not to suggest going up to the sitting room, in the hope that he would leave sooner. But Wetherslab seemed quite happy, drank soda water in small sips, and pointed out five elderly gentlemen in turn, the formula being the same. ‘You see so and so? Sir Harry Whatnot. Rich, but quite second class. You wouldn’t care for him at all.’ One by one the members of the Mission strolled away to bed, followed by murderous glances from Belcher who had given strict orders that he was not to be left alone with Featherston. The last I heard was F. saying: ‘You see that fellow sitting behind you?’ Bel. ‘Not having eyes in the back of my head, I don’t.’ F. (quite unperturbed) ‘He’s the Governor’s A.D.C. Quite your sort. I’ll bring him up.’ Bel. ‘You’ll do nothing of the sort. I won’t meet anyone tonight – first class, second class or third class!’ F. (sympathetically) ‘I expect you do get fed up with the kind of fellows you meet out here.’ I should not be at all surprised to learn tomorrow that (a) Featherston’s corpse had been recovered in the garden or (b) that Belcher had succumbed to an apoplectic fit!

[Friday] February 10

Darling Mother

I can’t in the least remember where I left off! And whether I told you about our day out with the British Manufacturers Representatives? They came for us with cars and took us out for a whole day’s motoring, over the ‘neck’ of Table Mountain, through lovely pine trees down a winding road to Camp’s Bay on the other side, and all along the coast road on the side of the mountains – just like Hope’s Nose and the New Cut at Torquay! (No matter where Millers go, they always say it is just like Torquay! But it is). We had lunch at Hout’s Bay – a most attractive Hotel with big shady trees growing up through the floor of the ‘stoep’ which I always disgrace myself by calling the verandah, and we ate at long tables under the shadow of the trees. I had Archie on one side (they put all husbands and wives next to each other) and a Mr Oldfield on the other side, and we had a most delightful conversation about vaccines and dog ticks! Belcher made an excellent speech.

Lunch at Hout’s Bay, from left to right: Agatha, Archie, Mrs Edwards, Mr Edwards, Major Featherston, Mrs Hiam, Mr Brown and Mr Hiam.

Then we drove on, through Constantia to see the vines, which I mistook for young tomato plants for some time! Fields of them, standing about 2ft high, like little currant bushes. We passed orchards of peach and pear trees also.

We had tea at the Majestic Hotel at Kalk Bay, and came home through Wyneberg, where most of the Cape Town people seem to live, and through Rhodes Avenue, where great oak trees meet overhead in an arch for about a mile or so, past the natural Zoo where Spring bok and Wilde beast (spelt wrong) [sic] walk about, with some lions and baboons in cages, and saw the Rhodes Memorial in the distance on the hill side. Young Ashby was with us, and at that moment delivered himself of the innocent remark: ‘Rhodes? That was the fellow who died quite rich, wasn’t it?’

Belcher is becoming very irritable. I don’t wonder really for his leg and foot are quite bad, bursting out in new places. The doctor says he must lie up and rest it, and he says he can’t afford the time. Bates had forgotten to get him more carbolic, and he’d had a tight boot on all day, the food in the hotel was atrocious, and the doctor has cut him down to one whiskey and soda a meal, so matters nearly reached a climax last night! Also, he is getting very fed up with Major Featherston, who attaches himself to Belcher like a faithful dog, and comes up at all hours of the day and night. He runs downs South Africa incessantly, apologising to us for the ‘second class’ people – ‘Not like my friends in New Zealand.’ In fact, we gather that the only first class people in South Africa are Prince Arthur of Connaught (‘I see a lot of him, of course’) his A.D.C. and – Major Featherston! He tells us all about his clothes, and the terrible duty he had to pay on ‘the half dozen 16 guinea suits I brought out from England – of course one can only get second rate stuffout here!’ However, he bent to pick up a handkerchief today, and Ashby, to his great delight, discovered a large patch of foreign material in the seat of the immaculate one’s trousers, and came to tell us the glad news in great glee. We all feel much better in consequence.

Saturday [February 11]

The industrious and perspiring Bates wrestled all yesterday to erect the B.E.E. models in the Chamber of Commerce, and this morning Sylvia and I went down to see them and afterwards tried on a lot of hideous hats in the town to recuperate after the strain of talking intelligently about them to the inevitable Wetherslab, and a red faced man called Archie Simpson, who was one of our hosts on the motor drive, on which occasion, he nearly drove Belcher into the Indian Ocean and frightened him to death.

This afternoon Archie and I went to a place beyond Muizenberg called Fish Hoek, and bathed. It’s the only place one can swim round here, either its surf bathing like Muizenberg, or else they have large tanks on the beach washed by every tide in which you feel rather like a fish in an aquarium! This was a lovely little place ringed round with mountains, white sand beach, and about six little white bungalows on the mountain side. No bathing huts (and no cover!) but a kind young man offered us a hutch where he kept fishing tackle, and we had a delicious bathe. Nevertheless, swimming is a little tame after surfing! We are going to buy light curved boards (that don’t jab you in the middle) and absolutely master the art. Archie loved Fish Hoek, of course, and would much prefer staying here to going up to Rhodesia. It is amusing after the crowded beaches in England to come to a place where when there are ten people and three children on the beach, you hear someone murmur: ‘How terribly crowded it is today!’

Archie in the sand dunes at Fish Hoek.

Sunday [February 12]

Today a selection of us went out to call on the Admiral at Simons town, Belcher having lunched with him yesterday. B. wanted to take Archie and me, but we agreed that that would hardly do, so I and Sylvia Hiam went with him and had a most pleasant time. Lady Goodenough has been ill and looked very frail, but was quite charming, and the Admiral is a jolly old boy, and took me all round the garden and showed me his ponies, and insisted that Archie and I must come out and lunch one day before we left Cape Town and I must bring my camera and take some views. He has two quite cheery daughters, one not out yet. The flag lieut. had an eye for me, I think – but the Admiral gave him no chance.

I fear Ceylon is quite off now. There are no boats from here – they all go to Bombay, and the Ormuz which we are trying to catch, touches at Colombo but not at Bombay. So we are cancelling the passages, and sailing direct for Australia from here somewhere about the 30 March, I expect.

Archie, Admiral, Lady Dorothy, Lady Goodenough and their dog Simon at Simonstown.

As this was mail day, posting this to catch up.

Love to all, Agatha.

MOUNT NELSON HOTEL CAPE TOWN

February 15 [Wednesday]

Dearest Mummy

The Hiams are a strange family! Neither Mrs Hiam nor Sylvia are enjoying this trip in the very least – but are longing to get back to England. The heat tries them, there is so much dust, the houses are so Dutch looking and unEnglish, the food is bad (true!) and (like Mrs Gummidge) if a mosquito bites them, it is worse for them than for other people – they feel it more! Then why come? I gather that Mr Hiam owns and farms the greater part of East Anglia. His father was a yeoman farmer in a rather large way, and the son conceived the brilliant idea of being the man who sold his father’s potatoes in London, with the result that he is worth just over a million. And yet, when you can afford to travel all over the world regardless of cost, you don’t enjoy it! As a matter of fact, he does – but only because of comparing the farming and agriculture generally, but still he is cheerful and always pleasant. I suppose it is rather dull for the girl. She’s a bit too young to enjoy any intelligent sight seeing, and there aren’t any dances or picnics or young peoples’ shows, and she is simply counting the days till she can get back to England. I find an evening spent with Mrs Hiam rather trying. She asks so many questions. I forget if I told you, but she said four times the other day what an extraordinary thing it was that there should be a Llandudno and a Clift on in South Africa ‘Just the same names as in England!’ I hinted that it was a phenomenon fairly often encountered in our colonies, but she repeated ‘Actually the same as in England’ and seemed to think it was a clear case of thought transference! They are quite attached to me. I iron their clothes for them, tell them what trams to take in the town to get back to the Hotel, and deal and shuffle for them when we play cards, neither of which accomplishments they can master!

Half holiday today! Archie came back from Muizenberg boasting that he can surf at last! Nobody believes him! But he rambles on while at the same time Hiam and Bates explain how really they practically got to the top of Table Mountain. Nobody believes them either, and Bates branches off earnestly to describe a particularly vicious looking spider that blocked his path, and how he distinctly heard a snake hiss. Bates has been convinced ever since leaving England (which he has never left before) that he is going into deadly peril and will never return alive. He insisted on the B.E.E. insuring his life before he started! Madeira he eyed askance as being full of pirates, and when a shark was seen at sea, it was sure to be Bates who saw it. Belcher has told him that there are young leopards on Table Mountain, and he believes it. We sent him a P.C. yesterday with a picture of a Puff Adder on it, and an earnest warning purporting to come from the ‘Society of the Protection of Visitors’ and Bates has been busily looking them up in the Telephone Directory, and cannot understand why no one seems to know where their offices are!

Thursday [February 16]

Yesterday afternoon, Mrs Blake and I went to the museum where we met two cousins of hers, one a very pretty girl, Marye Cole, who has been a great success with the Connaughts and others out here, and the other a Mrs Thomas who lives in Italy but has come out here to lecture on art. She dug out the head of the Museum and made him show us round. They have models from life of all the various Bushmen tribes, some of which are now dying out – extraordinary little women with enormous behinds trained out in a point! He explained them all very interestingly, and then we went on to the rock carvings and paintings done by prehistoric people. (Just like the reindeer ones, Punkie.) He showed how they were not just a lot of odd animals grouped together, but actually represented a particular hunt or drive. One eland’s legs look all out of drawing, but if you look closely, you see a tiny red spot, and the hunter indicated sketchily behind is holding a red tipped arrow, so you realise that the animals legs were supposed to be broken and that is why it is ‘all queer’. Most of the beasts have white foam coming out of their mouths, but one has red, and is sinking to the ground evidently dying. All the animals were finished minutely, but the hunters are very sketchy, and that is supposed to be on account of the superstitious idea that some tribes still hold – that it is unlucky to make a likeness of anyone – like the Egyptians wax figures. All the carved animals were begun the same way, from the round of the stomach, and if they saw the beginning had gone wrong, they abandoned it and began again.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/agata-kristi/the-grand-tour-letters-and-photographs-from-the-british-empir/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Агата Кристи

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Отдых, туризм

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Unpublished for 90 years, Agatha Christie’s extensive and evocative letters and photographs from her year-long round-the-world trip to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and America as part of the British trade mission for the famous 1924 Empire Exhibition.In 1922 Agatha Christie set sail on a 10-month voyage around the British Empire with her husband as part of a trade mission to promote the forthcoming British Empire Exhibition. Leaving her two-year-old daughter behind with her sister, Agatha set sail at the end of January and did not return until December, but she kept up a detailed weekly correspondence with her mother, describing in detail the exotic places and people she encountered as the mission travelled through South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii and Canada.The extensive and previously unpublished letters are accompanied by hundreds of photos taken on her portable camera as well as some of the original letters, postcards, newspaper cuttings and memorabilia collected by Agatha on her trip.Edited and introduced by Agatha Christie’s grandson, Mathew Prichard, this unique travelogue reveals a new side to Agatha Christie, demonstrating how her appetite for exotic plots and locations for her books began with this eye-opening trip, which took place just after only her second novel had been published (the first leg of the tour to South Africa is very clearly the inspiration for the book she wrote immediately afterwards, The Man in the Brown Suit). The letters are full of tales of seasickness and sunburn, motor trips and surf boarding, and encounters with welcoming locals and overbearing Colonials.The Grand Tour is a book steeped in history, sure to fascinate anyone interested in the lost world of the 1920s. Coming from the pen of Britain’s biggest literary export and the world’s most widely translated author, it is also a fitting tribute to Agatha Christie and is sure to fascinate her legions of worldwide fans.