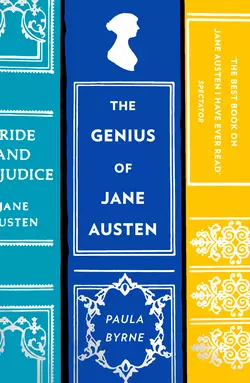

The Genius of Jane Austen: Her Love of Theatre and Why She Is a Hit in Hollywood

Paula Byrne

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Новое время

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 777.34 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A radical look at Jane Austen as you’ve never seen her – as a lover of farce, comic theatre and juvenilia. The Genius of Jane Austen celebrates Britain’s favourite novelist 200 years after her death and explores why her books make such awesome movies, time after time.Jane Austen loved the theatre. She learned much of her art from a long tradition of English comic drama and took joyous participation in amateur theatricals and her visits to the theatre in London and Bath. Her juvenilia, then ‘Sense and Sensibility’, ‘Pride and Prejudice’, ‘Mansfield Park’ and ‘Emma’ were shaped by the arts of theatrical comedy.Her admiration for drama’s dialogue, characterisation, plotting, exits and entrances is why she has been dramatised so successfully on screen in the last twenty years – and these versions are at the centre of her continuing fame, culminating in her celebration on £10 note.From the stage adaptations of Austen’s novels (including one called ‘Miss Elizabeth Bennet’ by A. A. Milne) to modern classics, including the BBC ‘Pride and Prejudice’ and ‘Persuasion’, Emma Thompson’s ‘Sense and Sensibility’, and the phenomenally brilliant and successful ‘Clueless’, ‘The Genius of Jane Austen’ presents an Austen not of prim manners and genteel calm, but filled with wild comedy and outrageous behaviour.