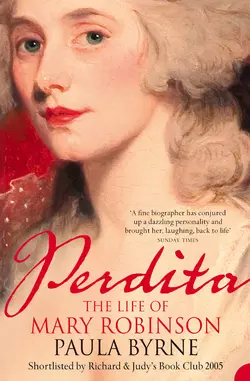

Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson

Paula Byrne

Sex, fame and scandal in the theatrical, literary and social circles of late 18th-century England.One of the most flamboyant women of the late-eighteenth century, Mary Robinson’s life was marked by reversals of fortune. After being raised by a middle-class father, Mary was married, at age fourteen, to Thomas Robinson. His dissipated lifestyle landed the couple and their baby in debtors' prison, where Mary wrote her first book of poetry and met lifelong friend Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire.On her release, Mary quickly became one of the most popular actresses of the day, famously playing Perdita in ‘The Winter’s Tale’ for a rapt audience that included the Prince of Wales, who fell madly in love with her. She later used his copious love letters for blackmail.This authoritative and engaging book presents a fascinating portrait of a woman who was variously darling of the London stage, a poet whose work was admired by Coleridge and a mistress to the most powerful men in England, and yet whose fortunes were nevertheless precarious, always on the brink of being squandered through recklessness, excess and passion.

Perdita

THE LIFE OF MARY ROBINSON

PAULA BYRNE

DEDICATION (#u44d7d24d-8fb6-525c-8e11-57fdb3214e53)

In memory of my grandmother,another Mary Robinson

EPIGRAPH (#u44d7d24d-8fb6-525c-8e11-57fdb3214e53)

I was delighted at the Play last Night, and was extremely moved by two scenes in it, especially as I was particularly interested in the appearance of the most beautiful Woman, that ever I beheld, who acted with such delicacy that she drew tears from my eyes.

(George, Prince of Wales)

There is not a woman in England so much talked of and so little known as Mrs Robinson.

(Morning Herald, 23 April 1784)

I was well acquainted with the late ingenious Mary Robinson, once the beautiful Perdita … the most interesting woman of her age.

(Sir Richard Phillips, publisher)

She is a woman of undoubted Genius … I never knew a human Being with so full a mind – bad, good, and indifferent, I grant you, but full, and overflowing.

(Samuel Taylor Coleridge)

I am allowed the power of changing my form, as suits the observation of the moment.

(Mary Robinson, writing as ‘The Sylphid’)

CONTENTS

COVER (#ucae53cef-df36-5b9d-b65b-212ea40b09c3)

TITLE PAGE (#u43343a4a-4d0c-5b9f-8476-71f9151031fc)

DEDICATION (#uc1ae9feb-76fb-5343-8895-f88ec480cec1)

EPIGRAPH (#u08436d96-d990-5063-ab69-3c837475dc61)

PROLOGUE (#u43072ab3-aa69-5340-9071-8efeb2ae64fb)

PART ONE: ACTRESS (#ufdafe8a8-be31-5b8b-b2fb-22ab51a1cded)

1. ‘During a Tempestuous Night’ (#u185e6cd8-c3a0-53f1-b293-b270a7d16f46)

2. A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World (#u16a6bddd-cf3d-5381-b094-a39fa52e45d3)

3. Wales (#u5aa9d713-14e3-5794-91a6-26a503828ef4)

4. Infidelity (#udc516f88-171b-5d77-a63f-de4452e876b4)

5. Debtors’ Prison (#u785cec07-9a08-5948-87c0-4e17c064dba0)

6. Drury Lane (#uedb70516-036b-53fd-afd8-623abeed7f5c)

7. A Woman in Demand (#u5d76d077-fa9a-5fee-a32f-d39c8222bf53)

PART TWO: CELEBRITY (#ucaf48a7d-2939-5d0e-b5f7-65759ed82f1b)

8. Florizel and Perdita (#u4bcc50b1-fd17-5701-94ce-70e7af6134c8)

9. A Very Public Affair (#litres_trial_promo)

10. The Rivals (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Blackmail (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Perdita and Marie Antoinette (#litres_trial_promo)

13. A Meeting in the Studio (#litres_trial_promo)

14. The Priestess of Taste (#litres_trial_promo)

15. The Ride to Dover (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Politics (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE: WOMAN OF LETTERS (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Exile (#litres_trial_promo)

18. Laura Maria (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Opium (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Author (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Nobody (#litres_trial_promo)

22. Radical (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Feminist (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Lyrical Tales (#litres_trial_promo)

25. ‘A Small but Brilliant Circle’ (#litres_trial_promo)

P.S. IDEAS, INTERVIEWS & FEATURES … (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Q AND A WITH PAULA BYRNE

LIFE AT A GLANCE (#litres_trial_promo)

TOP TEN BOOKS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE BOOK

CELEBRITY (#litres_trial_promo)

READ ON

HAVE YOU READ?

IF YOU LOVED THIS, YOU MIGHT LIKE … (#litres_trial_promo)

FIND OUT MORE (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

APPENDIX: THE MYSTERY OF MRS ROBINSON’S AGE (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

PRAISE (#litres_trial_promo)

OTHER WORKS (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_ae3cba89-768a-564b-aeab-a268ab56d2f0)

In the middle of a summer night in 1783 a young woman set off from London along the Dover road in pursuit of her lover. She had waited for him all evening in her private box at the Opera House. When he failed to appear, she sent her footman to his favourite haunts: the notorious gaming clubs Brooks’s and Weltje’s; the homes of his friends, the Prince of Wales, Charles James Fox, and Lord Malden. At 2 a.m. she heard the news that he had left for the Continent to escape his debtors. In a moment of panic and desperation, she hired a post chaise and ordered it to be driven to Dover. This decision was to have the most profound consequences for the woman famous and infamous in London society as ‘Perdita’.

In the course of the carriage ride she suffered a medical misadventure.

(#ulink_e70ee19d-94f6-561c-8aed-7ddfd36caf34) And she did not meet her lover at Dover: he had sailed from Southampton. Her life would never be the same again.

Born Mary Darby, she had been a teenage bride. As a young mother she was forced to live in debtors’ prison. But then, under her married name of Mary Robinson, she had been taken up by David Garrick, the greatest actor of the age, and had herself become a celebrated actress at Drury Lane. Many regarded her as the most beautiful woman in England. The young Prince of Wales – who would later become Prince Regent and then King George IV – had seen her in the part of Perdita and started sending her love letters signed ‘Florizel’. She held the dubious honour of being the first of his many mistresses.

In an age when most women were confined to the domestic sphere, Mary was a public face. She was gazed at on the stage and she gazed back from the walls of the Royal Academy and the studios of the men who painted her, including Sir Joshua Reynolds, who was to painting what Garrick was to theatre. The royal love affair also brought her image to the eighteenth-century equivalent of the television screen: the caricatures displayed in print-shop windows. Her notoriety increased when she became a prominent political campaigner. In quick succession, she was the mistress of Charles James Fox, the most charismatic politician of the age, and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, known as ‘Butcher’ Tarleton because of his exploits in the American War of Independence. The prince, the politician, the action hero: it is no wonder that she was the embodiment of – the word was much used at the time, not least by Mary herself – ‘celebrity’.

Her body was her greatest asset. When she came back from Paris with a new style of dress, everyone in the fashionable world wanted one like it. When she went shopping, she caused a traffic jam. What was she to do when that body was no longer admired and desired?

Fortunately, she had another asset: her voice. Whilst still a teenager, she had become a published poet. Because of her stage career, she had an intimate knowledge of Shakespeare’s language – and the ability to speak it. So, as her health gradually improved, she remade herself as a professional author. Having transformed herself from actress to author, she went on to experiment with a huge range of written voices, as is apparent from the variety of pseudonyms under which she wrote: Horace Juvenal, Tabitha Bramble, Laura Maria, Sappho, Anne Frances Randall. She completed seven novels (the first of them a runaway bestseller), two political tracts, several essays, two plays and literally hundreds of poems.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Actress, entertainer, author, provoker of scandal, fashion icon, sex object, darling of the gossip columns, self-promoter: one can see why she has been described as the Madonna of the eighteenth century.

(#litres_trial_promo) But celebrity has its flipside: oblivion. Mary Robinson had the unique distinction of being painted in a single season by the four great society artists of the age – Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, John Hoppner, and George Romney – and yet within a few years of her death the Gainsborough portrait was being catalogued under the anonymous title Portrait of a Lady with a Dog. In the twentieth century, despite the resurgence of the art of life-writing and the enormous interest in female authors, there was not a single biography of Robinson. Before the Second World War, she was considered suitable only for fictionalized treatments, historical romances and bodice-rippers with titles such as The ExquisitePerdita and The Lost One. In the 1950s her life was subordinated to that of the lover she thought she was pursuing to France.

(#ulink_0d0d5a7d-d8be-5c8a-ac0f-8fa7ebbde71c) A book on George IV and the women in his life did not even mention Mary’s name, despite the fact that she was his first love and he remained in touch with her for the rest of her life.

(#litres_trial_promo) Finally in the 1990s, feminist scholars began a serious reassessment of Robinson’s literary career. However, their work was aimed at a specialized audience of scholars and students of the Romantic period in literature.

(#litres_trial_promo)

When Mary Robinson began writing her autobiography, near the end of her life, there were two conflicting impulses at work. On the one hand, she needed to revisit her own youthful notoriety. She had been the most wronged woman in England and she wanted to put on record her side of the story of her relationship with the Prince of Wales. But at the same time, she wanted to be remembered as a completely different character: the woman of letters. As she wrote, she had in her possession letters from some of the finest minds of her generation – Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft – assuring her that she was, in Coleridge’s words, ‘a woman of genius’. Royal sex scandal and the literary life do not usually cohabit between the same printed sheets, but in a biography of the woman who went from ‘Mrs Robinson of Drury Lane’ to ‘the famous Perdita’ to ‘Mary Robinson, author’, they must.

The research for this book took me from the minuscule type of the gossip columns of the Morning Herald in the newspaper division of the British Library at Colindale in north London to the Gothic cloister of Bristol Minster, where Mary Robinson was born. I stood below the incomparable portraits of her in the Wallace Collection tucked away off busy Oxford Street and in stately homes both vast (Waddesdon Manor) and intimate (Chawton House). In the Print Room of the British Museum I pored over graphic and sometimes obscene caricatures of her; via the worldwide web I downloaded long-forgotten political pamphlets in which she figured prominently; in the New York Public Library, within earshot of the traffic on Fifth Avenue, I pieced together the letters in which Mary revealed her state of mind in the final months of her life, as she continued to write prolifically even as she struggled against illness and disability.

I found hitherto neglected letters and manuscripts scattered in the most unlikely places: in a private home in Surrey, I opened a cardboard folder and found the Prince of Wales’s account of the night he saw ‘Perdita’ at Drury Lane, written the very next day, in the first flush of his infatuation with her; in the Garrick Club, among the portraits of the great men of the theatre who launched Mary’s career, I discovered a letter in which she laid out her plan to rival the Lyrical Ballads of Wordsworth and Coleridge; and in one of the most securely guarded private houses in England – which I am prohibited from naming – I found the original manuscript of her Memoirs, which is subtly different from the published text. I became intimate with the perfectly proportioned face and the lively written voice of this remarkable woman. Yet as I was researching the book, people from many walks of life asked me who I was writing about: hardly any of them had heard of the eighteenth-century Mary Robinson. So I have sought to recreate her life, her world and her work, and to explain how it was that one of her contemporaries called her ‘the most interesting woman of her age’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_44ce5d9c-aa84-5a1b-aae3-0f4c1e54e5e9)As with many incidents in her life, the circumstances are not absolutely clear, as will be seen in chapter 15.

(#ulink_4eea274d-22eb-5e3d-bc45-f9d9da39fb7b)Robert Bass, The Green Dragoon: The Lives of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (New York, 1957) – as the title reveals, the main emphasis is on Tarleton’s military career. Though Bass undertook valuable archival research, his transcriptions were riddled with errors, he misdated key incidents, and he failed to notice many fascinating newspaper reports, references in memoirs, and other sources. It is no exaggeration to say that his inaccuracies outnumber his accuracies: if Bass says that an article appeared one November in the Morning Post, one may rest assured that it is to be found in December in the Morning Herald.

PART ONE Actress (#ulink_d318ace2-77e3-53bf-a8e5-3daa40276ad3)

CHAPTER 1 ‘During a Tempestuous Night’ (#ulink_ade32f98-29a7-5109-b216-1a646d603d7d)

The very finest powers of intellect, and the proudest specimens of mental labour, have frequently appeared in the more contracted circles of provincial society. Bristol and Bath have each sent forth their sons and daughters of genius.

Mary Robinson, ‘Present State of the Manners, Society, etc.

etc. of the Metropolis of England’

Horace Walpole described the city of Bristol as ‘the dirtiest great shop I ever saw’. Second only to London in size, it was renowned for the industry and commercial prowess of its people. ‘The Bristolians,’ it was said, ‘seem to live only to get and save money.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The streets and marketplaces were alive with crowds, prosperous gentlemen and ladies perambulated under the lime trees on College Green outside the minster, and seagulls circled in the air. A river cut through the centre, carrying the ships that made the city one of the world’s leading centres of trade. Sugar was the chief import, but it was not unusual to find articles in the Bristol Journal announcing the arrival of slave ships en route from Africa to the New World. Sometimes slaves would be kept for domestic service: in the parish register of the church of St Augustine the Less one finds the baptism of a negro named ‘Bristol’. Over the page is another entry: Polly – a variant of Mary – daughter of Nicholas and Hester Darby, baptized 19 July 1758.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Nicholas Darby was a prominent member of the Society of Merchant Venturers, based at the Merchants’ Hall in King Street, an association of overseas traders that was at the heart of Bristol’s commercial life. The merchant community supported a vibrant culture: a major theatre, concerts, assembly rooms, coffee houses, bookshops, and publishers. Bristol’s most famous literary son was born just five years before Mary. Thomas Chatterton, the ‘marvellous boy’, was the wunderkind of English poetry. His verse became a posthumous sensation in the years following his suicide (or accidental self-poisoning) at the age of 17. For Keats and Shelley, he was a hero; Mary Robinson and Samuel Taylor Coleridge both wrote odes in his memory.

Coleridge himself also developed Bristol connections. His friend and fellow poet Robert Southey, the son of a failed linen merchant, came from the city. The two young poets married the Bristolian Fricker sisters and it was on College Green, a stone’s throw from the house where Mary was born, that they hatched their ‘pantisocratic’ plan to establish a commune on the banks of the Susquehanna River.

Mary described her place of birth at the beginning of her Memoirs. She conjured up a hillside in Bristol, where a monastery belonging to the order of St Augustine had once stood beside the minster:

On this spot was built a private house, partly of simple and partly of modern architecture. The front faced a small garden, the gates of which opened to the Minster-Green (now called the College-Green): the west side was bounded by the Cathedral, and the back was supported by the antient cloisters of St Augustine’s monastery. A spot more calculated to inspire the soul with mournful meditation can scarcely be found amidst the monuments of antiquity.

She was born in a room that had been part of the original monastery. It was immediately over the cloisters, dark and Gothic with ‘casement windows that shed a dim mid-day gloom’. The chamber was reached ‘by a narrow winding staircase, at the foot of which an iron-spiked door led to the long gloomy path of cloistered solitude’. What better origin could there have been for a woman who grew up to write best-selling Gothic novels? If the Memoirs is to be believed, even the weather contributed to the atmosphere of foreboding on the night of her birth. ‘I have often heard my mother say that a more stormy hour she never remembered. The wind whistled round the dark pinnacles of the minster tower, and the rain beat in torrents against the casements of her chamber.’ ‘Through life,’ Mary continued, ‘the tempest has followed my footsteps.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Minster House was destroyed when the nave of Bristol Minster was enlarged in the Victorian era, but it is still possible to stand in the courtyard in front of the Minster School and see the cloister that supported the house in which Mary was born. And next door, in what is now the public library, one can look at an old engraving which reveals that the house was indeed tucked beneath the great Gothic windows and the mighty tower of the cathedral itself.

The family had Irish roots. Mary’s great-grandfather changed his name from MacDermott to Darby in order to inherit an Irish estate. Nicholas Darby was born in America and claimed kinship with Benjamin Franklin.

(#litres_trial_promo) As a young man he was engaged in the Newfoundland fishing trade in St John’s. His daughter described him as having a ‘strong mind, high spirit, and great personal intrepidity’, traits that could equally apply to herself.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Mary was always touchy about issues of rank and gentility. In her Memoirs she took pains to emphasize the respectability of the merchant classes. Her father had some success in cultivating the acquaintance of the aristocracy: in an unpublished handwritten note, Mary remarked with pride that ‘Lord Northington the Chancellor was my Godfather’ and that at her christening ‘the Hon Bertie Henley stood for him as proxy’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Mary’s mother, Hester, née Vanacott, made a romantic match with Nicholas Darby when she married him on 4 July 1749 in the small Somerset village of Donyatt. Hester was a descendant of a well-to-do family, the Seys of Boverton Castle in Glamorganshire, and a distant relation (by marriage) of the philosopher John Locke. Vivacious and popular, she had many suitors and her parents would have expected her to marry into a landed family. They did not approve of her union with Darby.

In 1752, three years after their marriage, Nicholas and Hester had a son, whom they named John.

(#litres_trial_promo) A daughter called Elizabeth followed in January 1755. She died of smallpox before she was 2 and was buried in October 1756. It was a great comfort to Nicholas and Hester when Mary was born just over a year later, on 27 November 1757.

(#ulink_1359ac3e-dc84-5b54-84b6-c41c765ce3c5)

In the days before vaccination, smallpox was a lethal threat to children. The disease took not only the infant Elizabeth, but probably also a younger brother, William, when he was 6. Another younger brother for Mary, named George, fared better: he and John both grew up to become ‘respectable’ merchants, trading at Leghorn (Livorno) in Italy.

Hester soon found that she had entered into an unhappy union. Nicholas spent much of his time in Newfoundland on business. By 1758, he was putting down roots there, joining with other merchants in an enterprise to build a new church. He returned to Bristol for the winter months, but he can only have been a shadowy presence in his daughter’s early life.

The Darby boys were extremely handsome, with auburn hair and blue eyes. Mary took after her father; she described her own childhood looks as ‘swarthy’, with enormous eyes set in a small, delicate face. She was a dreamy, melancholy, and pensive child who revelled in the gloominess of her surroundings in the minster. The children’s nursery was so close to the great aisle that the peal of the organ could be heard at morning and evening service. Mary would creep out of her nursery on her own and perch on the winding staircase to listen to the music: ‘I can at this moment recall to memory the sensations I then experienced, the tones that seemed to thrill through my heart, the longing which I felt to unite my feeble voice to the full anthem, and the awful though sublime impression which the church service never failed to make upon my feelings.’ Rather than playing on College Green with her brothers she would creep into the minster to sit beneath the lectern in the form of a great eagle that held up the huge Bible. The only person who could keep her away from her self-imposed exile there was the stern sexton and bell-ringer she named Black John, ‘from the colour of his beard and complexion’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

As soon as she learnt to read, she recited the epitaphs and inscriptions on the tombstones and monuments. Before she was 7 years old, she had memorized several elegiac poems that were typical of the verse of the eighteenth century. Her taste in music was as mournful as her taste in poetry.

Mary confessed that the events of her life had been ‘more or less marked by the progressive evils of a too acute sensibility’. One thinks here of Jane Austen’s first published novel, Sense and Sensibility, with its satirical portrait of the ultra-sensitive Marianne Dashwood: she bears more than a passing resemblance to the melancholy young Mary Darby, quoting morbid poetry and thoroughly enjoying the misery of playing sombre music and being left in solitary contemplation. As a writer, Mary was always acutely aware of her audience: her image of herself in the Memoirs as a child of sensibility was designed to appeal to the numerous readers of Gothic novels and sentimental fiction. At the same time, her self-image appealed to the romantic myth of the writer as a natural genius who begins as a precociously talented but lonely child escaping into the world of imagination.

Though Mary presented herself as a ‘natural’ genius, she was the beneficiary of improvements in education and the growth of printed literature aimed at a young audience. This was a period when private schools for girls of middling rank sprang up all over England. Bristol was the home of Hannah More, playwright, novelist, Evangelical reformer, and political writer. Though Hannah became famous for rectitude and Mary for scandal, their lives were curiously parallel: born and bred in Bristol, each of them had a theatrical career that began under the patronage of David Garrick and each then turned to the art of the novel. In the 1790s they both became associated with contentious debates about women’s education.

Mary attended a school run by Hannah More and her sisters. An upmarket ladies’ academy, it had opened in 1758 in Trinity Street, behind the minster, just a few hundred yards from Mary’s birthplace. The curriculum concentrated on ‘French, Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, and Needlework’. A recruitment advertisement added that ‘A Dancing Master will properly attend.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The school was immensely popular and four years later moved to 43 Park Street, halfway up the hill towards the genteel district of Clifton. When Mary Darby attended, the enrolment had risen to sixty pupils. Each of the More sisters took responsibility for a different ‘department’ of the curriculum, with – in Mary’s words – ‘zeal, good sense and ability’. The earnest and erudite Hannah ‘divided her hours between the arduous task “of teaching the young ideas how to shoot,” and exemplifying by works of taste and fancy the powers of a mind already so cultivated’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the summer of 1764 Bristol was in the grip of theatre mania. The famous London star William Powell played King Lear with a force said to rival that of the great Garrick himself. Within two years Powell was combining management with performance at a new building in the city centre. The first theatre in England to be built with a semicircular auditorium, it had nine dress boxes and eight upper side boxes, all inscribed with the names of renowned dramatists and literary figures.

The highlight of the first season in this new Theatre Royal was another King Lear, with Powell in the lead once again and his wife Elizabeth playing Cordelia. Powell had become very friendly with Hannah More, and she wrote an uplifting prologue for the performance. The whole school turned out for the play. It was the 8-year-old Mary Darby’s first visit to the theatre. She vividly remembered the ‘great actor’ of whom Chatterton said ‘No single part is thine, thou’rt all in all.’

(#litres_trial_promo) She was less taken by the performance of his wife who played Cordelia without ‘sufficient éclat to render the profession an object for her future exertions’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Among Mary’s school friends were Powell’s two daughters and the future actress Priscilla Hopkins, who would later become the wife of John Kemble and sister-in-law of Sarah Siddons, the most famous actress in Britain. The girls developed a passion for theatre together.

Hannah More continued to be fascinated by the theatre. She wrote a pastoral verse comedy called The Search after Happiness, which was acted by the schoolgirls. It advocates a doctrine of female modesty and submission that would be echoed in the anti-feminist tracts she wrote in later life. One of the characters is an ambitious girl who longs to ‘burst those female bonds, which held my sex in awe’ in order to pursue fame and fortune: ‘I sigh’d for fame, I languished for renown, / I would be prais’d, caress’d, admir’d, and known.’ It is tempting to see the young Mary Darby playing this part, and hearing her aspirations rebuked by another character: ‘Would she the privilege of Man invade? …/ For Woman shines but in her proper sphere.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

By the end of the century Hannah More had turned herself into one of the most formidable conservative propagandists of the age. She deeply resented her connection with her old pupil, the infamous Perdita. That one of the most reviled women of the era was taught by one of the most revered was an irony not lost on the bluestocking Mrs Thrale: ‘Of all Biographical Anecdotes none ever struck me more forcibly than the one saying how Hannah More la Dévote was the person who educated fair Perdita la Pécheresse.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Mary, in turn, made it abundantly clear that her literary gifts owed little debt to Hannah and her sisters. She stressed that the education she received from the school was merely in feminine accomplishments of the sort that were required for the marriage market. Women were expected to be ornaments to society and, once married, to be modest and retiring creatures confined to the domestic sphere rather than competing with men in the public domain.

As the daughter of a prosperous merchant, Mary benefited from the privileges that could be bought by new money. The distinguished musician Edmund Broderip taught her music on an expensive Kirkman harpsichord bought by her father. The family moved to a larger, more elegant house as Nicholas Darby, keen to show off the fruits of his upward mobility, insisted upon living like a gentleman, buying expensive plate, sumptuous silk furniture, foreign wine, and luxurious food, displaying ‘that warm hospitality which is often the characteristic of a British merchant’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He ensured that his daughter lived in the best style. Her bed was of the richest crimson damask; her dresses, ordered from London, were of the finest cambric. The family spent the summer months on gentrified Clifton Hill in order to benefit from the clearer air. Darby’s appetite for ‘the good things of the world’ would be inherited by his daughter.

Mrs Darby, meanwhile, provided emotional security. Unlike many of the other girls at the More sisters’ school, Mary never boarded: she did not ‘pass a night of separation from the fondest of mothers’. In retrospect, she considered herself overindulged, suggesting that her mother’s only fault was ‘a too tender care’, a tendency to spoil and flatter her children: ‘the darlings of her bosom were dressed, waited on, watched, and indulged with a degree of fondness bordering on folly’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Given that Nicholas Darby was absent abroad for much of the time, it is not surprising that Hester threw so much into her children. Mary implies that an absent father and an indulgent mother proved a dangerous combination for a headstrong girl like herself.

The Memoirs paints a picture of Mary’s early childhood as a fairy-tale existence, a paradise lost. Her life changed for ever, she says, when she was in her ninth year. Nicholas Darby had a lifelong history of travelling, fishing, and trading in the far north of Newfoundland. In the early 1760s he was acting as spokesman for the Society of Merchant Venturers, advising the Government on the defence of Newfoundland, which was a key strategic outpost fought over by the British and French during the Seven Years War. Then in 1765 he became obsessed with what Mary describes as an ‘eccentric’ plan, a scheme ‘as wild and romantic as it was perilous to hazard, which was no less than that of establishing a whale fishery on the coast of Labrador; and of civilizing the Esquimaux Indians, in order to employ them in the extensive undertaking’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

This was dangerous territory. Not only was the weather extremely inclement, but the area in question – the Strait of Belle Isle – had only been held in British hands for a couple of years. But Darby had some powerful backers: Mary records that his scheme was given approval by the Governor of Newfoundland, Lord Chatham (William Pitt the Elder) and ‘several equally distinguished personages’. The venture seemed ‘full of promise’. Darby dreamed that the day might come when, thanks to him, British America could rival the whale industry of Greenland.

Having got permission from the Government, he told his family that the scheme would require his full-time residence in America for a minimum of two years. Hester was appalled by the idea. The northern wastes were no place for children, so accompanying her husband would have meant leaving her beloved sons and daughter to complete their education at boarding schools in England. She also had a phobia of the ocean. The decision to stay with her children would cost Hester her marriage. Nicholas duly sailed for America. The eldest boy John was placed in a mercantile house at Leghorn, whilst Mary, William, and George stayed with Hester in Bristol.

At first, Nicholas wrote regularly and affectionately. But his letters gradually became less frequent, and when they did arrive they began to seem dutiful and perfunctory. Then there was a long period of silence. And finally ‘the dreadful secret was unfolded’: Darby had acquired a mistress, Elenor, who, as Mary wryly testified, was only too happy to ‘brave the stormy ocean’ alongside him. She ‘consented to remain two years with him in the frozen wilds of America’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Darby had sailed from England to Chateau Bay with 150 men. He was then given headquarters on Cape Charles, where he constructed lodgings, a workshop, and a landing stage. Fishing began well, but then the local Inuit burned his boats and destroyed his crucial supply of salt. His men fought with each other and refused to winter on the coast. He made a second attempt a year later, in partnership with a fellow merchant, returning with new men and more sophisticated equipment. But more fighting ensued and in the summer of 1767 ten men were arrested on murder charges. Then in November, around the time of Mary’s tenth birthday, the Labrador project came to a violent end: another band of Inuit attacked a crew preparing for winter sealing, killed three men, burned Darby’s settlement, and set his boats adrift. Thousands of pounds’ worth of ships and equipment were destroyed. ‘The island of promise’ had turned into a ‘scene of barbarous desolation’ – though Mary’s account characteristically exaggerates the slaughter, turning the three casualties into the murder of ‘many of his people’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Darby’s patrons refused to honour their promise of financial protection and, with more losses incurred, he dissolved his partnership and set in train the sale of the family home.

Back in Bristol, Hester Darby faced a series of calamities: the shame that came with the news that her husband was residing in America with his mistress, the financial losses that would cost her everything, and the death – from smallpox or possibly measles – of Mary’s 6-year-old brother William. On his return to London, Nicholas lived with his mistress Elenor, but the manuscript of Mary’s Memoirs has an intriguing memorandum, excluded from the published text: ‘Esquemaux Indians brought over by my father, a woman and a boy.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Could this have been another mistress? And could it then be that Mary had an illegitimate half-Inuit half-brother?

Mary always felt torn between pride in her father’s achievements and resentment at his abandonment of the family. Her ambivalence can be seen in the way that she emphasizes his dual nationality. When she speaks of his bold and restless spirit, and his love of sea life, she ascribes this to his status as an American seafarer, yet at other times he is that stalwart of the community, a ‘British merchant’. Mary blamed her father’s mistress for bewitching his senses at a time when he was isolated in America, away from his wife and family. She herself learnt a valuable lesson at a particularly vulnerable age: loss of fortune and position swiftly loses friends. Dropped by the people who had been happy to take advantage of their former prosperity, the family were left bereft.

A year later, Hester, Mary, and the surviving younger son, George, were summoned to London to their father’s lodgings in fashionable Spring Gardens, near the famous Vauxhall pleasure gardens. Hester was unsure as to whether to expect ‘the freezing scorn, or the contrite glances, of either an estranged or repentant husband’.

(#litres_trial_promo) His ‘coldly civil’ letter had ‘requested particularly’ that she should bring the children with her: this ought to have been enough to make her realize that the meeting would be a farewell, not a reunion.

When they met, her father was in tears and could barely speak. The embrace he gave his wife was ‘cold’ – and it was the last she was to receive from him. Once the initial recriminations had blown over, Nicholas set out his plans. The children were to be placed at schools in London, while his wife was to board with a respectable clergyman’s family. He would be returning across the Atlantic. And, indeed, the following year he launched a new and much more successful venture in Labrador, this time employing experienced Canadian fishermen.

The next stage of Mary’s education was to be crucial to her vocation as a writer. She was sent to a school in Chelsea and came under the tuition of a brilliant and accomplished woman, Meribah Lorrington. Lorrington was highly unconventional in that she had been given a masculine education by her schoolteacher father, and was as well versed in the classics as she was in the modern languages, arithmetic, and astronomy. She was the living embodiment of a character type that Mary would fictionalize in several of her novels, the female who benefits from the education usually reserved for boys.

Mary worshipped her teacher, elevating her influence far above that of the More sisters: ‘All that I ever learned I acquired from this extraordinary woman.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The classical education she was given in Chelsea meant that in the long term her writings would demand a respect that was not often granted to female authors. There is an especially striking breadth of classical allusion in her feminist treatise A Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of Mental Subordination.

Pupil and teacher became close companions, even sharing the same bedroom. Mary dates her love for books from this relationship: ‘I applied rigidly to study, and acquired a taste for books, which has never, from that time, deserted me.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The women read to one another and Mary began composing verses, some of which were included in her first collection of poems, which she was to publish from debtors’ prison. In Mary’s narrative of her own life, her intellect first blossoms in an all-female community, with Meribah and half a dozen fellow pupils (among whom Mary is clearly singled out as the favourite). Far from aligning herself with the highly respectable Hannah More, she chooses to identify Lorrington as her mentor – and then goes on to reveal that she was an incorrigible drunkard.

Mary often complained of the contemptuous treatment that she received from her own sex, but she paid the utmost respect to the women who inspired and supported her, especially in her writing career. As Meribah Lorrington was credited for encouraging her juvenile writing, so Mary’s first literary patron was another woman of dubious reputation, Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire. Mary adored both women, though Meribah was a hopeless alcoholic and Georgiana an equally addicted gambler.

Mary accepted the explanation that Meribah gave for her addiction to drink: she was grief-stricken by the death of her husband and was the victim of a bullying, disciplinarian father, a stern-speaking silver-bearded Anabaptist who wandered round the girls’ schoolroom wearing nothing but a loose flowing robe which made him look like a necromancer. Mary noticed that the presence of the father always made the daughter reach for the bottle.

Meribah Lorrington’s ‘state of confirmed intoxication’ even during teaching hours led to the demise of the Chelsea school. Some time later, Mary discovered a drunken beggar woman at dusk in the street. She gave her money, then, to her surprise, the woman said, ‘Sweet girl, you are still the angel I ever knew you.’ Their eyes met and Mary was horrified to discover that it was her old teacher. She took her home, gave her fresh clothes, and asked her where she lived. Meribah refused to say, but promised she would call again in a few days. She never did. Years later, Mary learned that her brilliant but flawed mentor had died a drunk in the Chelsea workhouse.

Mary describes herself in her Memoirs as well developed for her age, tall and slender. At the age of 10, she says, she looked 13. During her fourteen-month period boarding at the Lorrington Academy, she visited her mother every Sunday. One afternoon over tea she had a marriage proposal from a friend of her father’s. Hester was a little surprised; she asked her visitor how old he thought her daughter was. ‘About sixteen,’ he replied. Hester informed him that Mary was still only 12. He found this hard to believe, given that she was such a well-developed girl both physically and intellectually, but he was prepared to wait – he was a captain in the Navy, just off on a two-year voyage. He had great prospects for the future and hoped that Mary might still be unattached on his return. Just a few months later he perished at sea.

In this version of Mary’s first encounter with male desire, she is the innocent: a child, albeit with the body of a woman. The first ‘biography’ of her, published at the height of her public fame in 1784, tells a very different story. The Memoirs of Perdita is a source that must be treated with great caution, since – as will be seen – it was written with both a political and a pornographic agenda. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the book’s anonymous author had a very well-informed source. The ‘editor’ claimed in his introduction that ‘the circumstances of her life were communicated by one who has for several years been her confidant, and to whose pen she has been indebted for much news paper panegyric’ – a description that very much suggests Henry Bate of the Morning Herald, a key figure in Mary’s story. According to the ‘editor’ of The Memoirs of Perdita, ‘the following history may with propriety be said to be dictated by herself: many of the mere private transactions were indisputably furnished by her; nor could they possibly originate from any other source’.

(#litres_trial_promo) In some instances this is true: The Memoirs of Perdita published personal information about Mary’s life that was not previously in the public domain. In other instances, however, these supposed memoirs can safely be assumed to offer nothing more than malicious fantasy.

According to The Memoirs of Perdita, Mary’s first love affair occurred soon after the Darbys moved to London. Her father supposedly brought home a handsome young midshipman called Henry, who was allowed ‘private interviews’ and ‘little rambles’ with Mary. They went boating together on the Thames. On one occasion, they stopped for refreshments at Richmond. The only room the landlord had available in which to serve them with a glass of wine and a biscuit happened to be a bedchamber – which had crimson curtains that matched the ‘natural blush’ to which Mary was excited by the sight of the bed. The young midshipman duly took her hand and sat her with him on the white counterpane. ‘Perdita’s blushes returned – and Henry kissed them away – She fell into his arms – then sunk down together on the bed. – The irresistible impulse of nature, in a moment carried them into those regions of ecstatic bliss, where sense and thought lie dissolved in the rapture of mutual enjoyment.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The affair supposedly lasted for some time, until the ‘jovial tar’ was summoned back to his ship, never to be seen again. In all probability, ‘Henry’ is pure invention, perhaps spun at second hand from some passing remark about the sailor’s proposal. After all, given that Nicholas Darby was estranged from his family, he was not there to introduce a midshipman into the household. But it would be unwise to dismiss out of hand the possibility that the young Mary – steeped as she was in poetry and romance – might have had some kind of sexual awakening in her early teens.

Mary was moved to a more orthodox boarding school in Battersea, run by a less colourful but nevertheless ‘lively, sensible and accomplished woman’ named Mrs Leigh.

(#litres_trial_promo) Nicholas Darby then stopped sending money for his children’s education. The resolute Hester took matters into her own hands and set up her own dame school in Little Chelsea. The teenage Mary became a teacher of English language, responsible for prose and verse compositions during the week and the reading of ‘sacred and moral lessons, on saints’-days and Sunday evenings’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Readers of her Memoirs would have been at best amused at the idea of one of the most notorious women of the age presenting herself as a teacher of morals and religion. Mary also had responsibility for supervising the pupils’ wardrobes, and making sure that they were properly dressed and undressed by the servants.

In 1770, Nicholas Darby ran into more problems. Just as he had a thousand pounds’ worth of seal skins ready for market, a British military officer arrived at his Labrador fishery and confiscated all his produce and tackle on the grounds that he was illegally employing Frenchmen and using French rather than British equipment. He was left marooned. He eventually made it back to London and asked the Board of Trade for compensation, claiming that he did not know that his Canadian crew were actually French subjects. The Board of Trade passed the buck, saying it had no jurisdiction in the case. Nicholas had a moral victory when the Court of King’s Bench awarded him £650 damages against the Lieutenant who had seized the goods, but the money was uncollectible. In the circumstances, one might have expected him to be grateful for his estranged wife’s initiative in establishing a school. But he was a proud man: ‘he considered his name as disgraced, his conjugal reputation tarnished, by the public mode which his wife had adopted for revealing to the world her unprotected situation’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He lived openly with his mistress, but could not abide seeing his wife publicly revealed as someone akin to an impoverished widow or spinster. He demanded that the school be closed immediately. It had lasted for less than a year.

Hester and her children moved to Marylebone. Like Chelsea, this was an expanding village on the edge of London, but it had a less rural feel and was fast being recognized as an integral part of the metropolis. Mary reverted from teacher to pupil, finishing her education at Oxford House, situated near the top of Marylebone High Street, bordering on Marylebone Gardens. Nicholas Darby and his mistress Elenor settled in the more fashionable and gentrified Green Street, off Grosvenor Square in Mayfair, a district that was becoming increasingly popular with merchants and rich shopkeepers as well as the gentry.

Mary must have been acutely conscious of the differences in lifestyle between her mother and her father. She sometimes accompanied her father on walks in the fields nearby, where he confessed that he rather regretted his ‘fatal attachment’ to his mistress – they had now been together so long and been through so much that it was impossible to dissolve the relationship. On one of their walks, they called on the Earl of Northington, a handsome young rake and politician, whose father had been one of the sponsors of Darby’s Labrador schemes. They were very well received, with Mary being presented as the goddaughter of the older Northington (now deceased). In later years, she did not deny rumours that she might have been the old Lord’s illegitimate daughter. The young Lord, meanwhile, treated her with ‘the most flattering and gratifying civility’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

When Nicholas returned to America, Hester moved her children to Southampton Buildings in Chancery Lane. This was lawyers’ territory, backing onto Lincoln’s Inn. She had placed herself under the protection of Samuel Cox, a lawyer. Perhaps she had applied to him for legal help after the separation from Nicholas became final. Being ‘under the protection’ of a man was usually code for sexual involvement, so it may have been more than a professional relationship.

It was during her time at Oxford House that Mary was drawn towards the stage. The governess, Mrs Hervey, spotted her talent for ‘dramatic exhibitions’, and persuaded Hester to let her daughter try for the stage, despite the fact that it was not considered to be a respectable career. Hester was persuaded that there were actresses who ‘preserved an unspotted fame’. Nicholas obviously had his doubts. Upon setting off on his new overseas adventure, he left his wife with a chilling injunction to ‘Take care that no dishonour falls upon my daughter. If she is not safe at my return I will annihilate you.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The school’s dancing master was also ballet master at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden. Through him, Mary was introduced to an actor called Thomas Hull, who was impressed by her recitation of lines from Nicholas Rowe’s tragedy Jane Shore of 1714. But nothing came of the audition. Mary did not despair and she was rewarded with a much greater opportunity. Her mother’s protector Samuel Cox knew Dr Samuel Johnson and that was enough to open the door of Johnson’s old pupil and friend, David Garrick.

What was Mary Darby like at the time that she met Garrick? Though she may have been a plain child with dark swarthy looks, she had become a very beautiful teenager. She had curly, dark auburn hair and soft blue eyes that were to enchant men from the Prince of Wales to Samuel Taylor Coleridge. She had dimples in her cheeks. But there was always an elusive quality to her beauty. Sir Joshua Reynolds’s pupil, James Northcote, remarked that even his master’s portraits of her were failures because ‘the extreme beauty’ of her was ‘quite beyond his power’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_5a98f249-cf28-537e-b3d3-c559c4ef7d9c)See Appendix for the uncertainty over the year of Mary’s birth.

CHAPTER 2 A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World (#ulink_a0601865-44c9-576d-ba21-5450db7d4a36)

As London is the great emporium of commerce, it is also the centre of attraction for the full exercise of talents, and the liberal display of all that can embellish the arts and sciences.

Mary Robinson, ‘Present State of the Manners, Society, etc.

etc. of the Metropolis of England’

London was like nowhere else in the world. Bigger than any other city in Europe, with a population more than ten times that of Bristol, it was a place of extremes. Riches and squalor, grandeur and wretchedness, appeared cheek-by-jowl. This was an era of unprecedented consumerism: for companionship and entertainment there were coffee houses, taverns, brothels, parks, pleasure gardens, and theatres. Above all there were shops. Napoleon had good reason to dismiss the English as a nation of shopkeepers. By the time of Mary’s arrival in the metropolis, London had one for every thirty residents. Oxford Street alone boasted over a hundred and fifty. Everything was on display, from plate laden in silversmiths’ shops to fruits and spices piled high on street-barrows. Tea, coffee, sugar, pepper, tobacco, chocolate, and textiles – the ‘fruits of empire’ – were sold in vast quantities.

(#litres_trial_promo) There were print shops, book shops, milliners, linen drapers, silk mercers, jewellery shops, shoe shops, toy shops, confectioners. London was the epicentre of fashion, a place to gaze and be gazed at. It was an urban stage, and few understood this as well as Mary.

For the young poet William Wordsworth, London’s inherent theatricality was disturbing. His section on ‘Residence in London’ in his autobiographical poem The Prelude describes with unease ‘the moving pageant’, the ‘shifting pantomimic scenes’, the ‘great stage’, and the ‘public shows’. For Wordsworth, the gaudy display and excessive showiness of the city signalled a lack of inner authenticity; ‘the quick dance of colours, lights and forms’ was an alarming ‘Babel din’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Mary Robinson also captured the cacophony of urban life in her poem ‘London’s Summer Morning’, but she relished what Wordsworth abhorred:

Who has not wak’d to list the busy sounds

Of summer’s morning, in the sultry smoke

Of noisy London? On the pavement hot

The sooty chimney-boy, with dingy face

And tatter’d covering, shrilly bawls his trade,

Rousing the sleepy housemaid. At the door

The milk-pail rattles, and the tinkling bell

Proclaims the dustman’s office, while the street

Is lost in clouds impervious. Now begins

The din of hackney-coaches, wagons, carts;

While tinmen’s shops, and noisy trunk-makers,

Knife-grinders, coopers, squeaking cork-cutters,

Fruit-barrows, and the hunger-giving cries

Of vegetable vendors, fill the air.

Now ev’ry shop displays its varied trade,

And the fresh-sprinkled pavement cools the feet

Of early walkers.

(#litres_trial_promo)

She finds poetry in everything from the dustman to the ‘neat girl, / Tripping with bandbox lightly’ to the street vendor of second-hand clothes.

Mary was to experience London in its entirety, from debtors’ prison to parties given in her honour as the Prince’s consort at St James’s Palace. She became notorious for her self-promotion and her skill in anticipating the next new thing, be that in fashion or poetry. But she also grasped the very essence of urban culture in the late eighteenth century in a way that eluded Wordsworth. She knew that in order to survive and thrive in the new consumer society, she had to work to sell her wares. The literary marketplace was as crowded as the London streets and it took guts, brashness, and ostentation to make your voice heard – especially if you were a woman.

She must have felt some trepidation at meeting Garrick: ‘King’ David, the man who had single-handedly transformed the theatre world, acting on stage with unprecedented naturalism, producing behind the scenes with prodigious energy, and above all conferring on his profession a respectability it had never had before.

The 14-year-old girl was summoned to the actor’s elegant and grand new house in Adelphi Terrace, designed by the fashionable Adam brothers and overlooking the Thames. The Garricks had recently moved there and had furnished it lavishly. Mary would have entered through the large hall, with its imposing pillars, and then been shown into the magnificent first-floor drawing room, with its elaborate plaster ceiling crowned by a central circular panel of Venus surrounded by nine medallion paintings of the Graces. Garrick would have soon put her at ease with his good humour and liveliness. His wife, Eva Maria Veigel, a former dancer, was usually at his side and was especially considerate to young girls, as the future dramatist and novelist Fanny Burney testified when she visited the Garricks at their new house the same year: ‘Mrs Garrick received us with a politeness and sweetness of manners, inseparable from her.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Garrick, always susceptible to beauty, was captivated by Mary’s loveliness. Her voice reminded him of Susannah Cibber, an actress and singer he had favoured in his youth. An added attraction came in the form of Mary’s long, shapely legs, ideal for the highly popular ‘breeches roles’ that were required of actresses on the Georgian stage. In an age when women wore full-length dresses all the time, the actress who cross-dressed in boys’ clothing – as Shakespeare’s Rosalind and Viola, and in dozens of similar roles in eighteenth-century comedies – provided a unique spectacle: the public exhibition of the shape of a female leg.

Garrick’s personal interest was in no sense salacious. His faith in this young unknown was typical of his unfailing support for women in the theatre. His patronage of female actresses and female playwrights was highly unusual in a society that discouraged women from the stage and still regarded actresses as little better than prostitutes. Garrick ‘discovered’ many a young actress and gave playwrights such as Hannah More and Hannah Cowley their first break. In return these young women adored him and his wife.

He offered to train Mary for the part of Cordelia to his own King Lear in the version of Shakespeare’s tragedy that he had reworked from Nahum Tate’s Restoration era adaptation, in which Cordelia is happily married off to Edgar instead of being hanged. Garrick was now in his fifties, beginning to suffer from gout and gallstones. He was conserving his energy, limiting the number of his appearances on stage. Lear, which he had been playing since he was 25, was not only one of his most celebrated but also one of his most demanding roles. This late in his career, it was an extraordinary gamble to entrust Cordelia to a complete unknown. He and Mary spent hours preparing for her debut in the role.

But it was not all work: in the Memoirs, she draws a charming picture of them dancing minuets (Garrick was an excellent dancer) and singing the favourite ballads of the day. Her memory remained vivid: ‘Never shall I forget the enchanting hours which I passed in Mr Garrick’s society: he appeared to me as one who possessed more power, both to awe and to attract, than any man I ever met with.’

(#litres_trial_promo) She also noticed his dark side: ‘His smile was fascinating; but he had at times a restless peevishness of tone which excessively affected his hearer; at least it affected me so that I never shall forget it.’ His temper was renowned. Fanny Burney reported in her diary that Dr Johnson attributed Garrick’s faults to ‘the fire and hastiness of his temper’. Burney loved Garrick and was mesmerized by the lustre of his ‘brilliant, piercing eyes’, but she also noted that ‘he is almost perpetually giving offence to some of his friends’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Others could feel irritated by his attention-seeking behaviour. As his friend Oliver Goldsmith put it, he was always natural, simple and unaffected on stage – ‘’Twas only when he was off, he was acting.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Garrick had a genius for self-publicity and was astonishingly energetic: in the light of Mary’s subsequent career, one might say that he was her perfect role model. Mary adored him and took his advice seriously. He advised her to frequent Drury Lane and familiarize herself with its practices before she made her debut. She quickly became known as Garrick’s new protégée and drew a swarm of admirers. This was Mary’s first taste of celebrity and she loved the ‘buzz’ (her term). While Hester fretted about her daughter’s reputation, Mary was confident that she could tread the thin line between fame and infamy: ‘my ardent fancy was busied in contemplating a thousand triumphs, in which my vanity would be publicly gratified, without the smallest sacrifice of my private character’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Hester worried that her daughter was making too much of a stir amongst the young rakes who frequented the theatre just to flirt with the latest ingénue. She kept her eye on one man in particular. In her Memoirs Mary described him as a graceful and handsome officer – a Captain – who was very well connected, though she declined to name him. After a brief courtship, and offers of marriage, Hester discovered that he was already married. Mary was informed of the deception, but brushed it off: ‘I felt little regret in the loss of a husband, when I reflected that a matrimonial alliance would have compelled me to relinquish my theatrical profession.’ Another rich suitor came forward at this time, but, to Mary’s horror, he was old enough to be her grandfather. She had set her heart on being an actress: ‘the drama, the delightful drama, seemed the very criterion of all human happiness’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

She was naturally flirtatious and her beauty attracted a stream of admirers. One of her most persistent suitors was a young solicitor’s clerk, who lived across the way from her lodgings. He would sit in the window staring at the fresh-faced Mary. He was languorous and sickly looking, which would have appealed to a girl of strong ‘sensibility’. Mrs Darby’s response to the flirtation was to keep the lower shutters of the windows permanently closed. Fancying ‘every man a seducer, and every hour an hour of accumulating peril’, she sighed for the day when her daughter would be ‘well married’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The articled clerk was named Thomas Robinson. He was training with the firm of Vernon and Elderton in the buildings opposite. He persuaded a friend (a junior colleague of Samuel Cox) to invite Mary and her mother to a dinner party out in Greenwich, without disclosing that Robinson himself would be present. Mother and daughter opened the door of their carriage only to find him ready to hand them down. Hester was duly horrified while Mary professed herself only ‘confused’. Fortunately, though, she had dressed very carefully for dinner, sensing that a conquest was afoot: ‘it was then the fashion to wear silks. I remember that I wore a nightgown of pale blue lustring, with a chip hat, trimmed with ribbands of the same colour.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The English nightgown was a simple, flowing shift dress that had been popular for many seasons. It was modest in comparison to the revolutionary ‘Perdita’ chemise that Mary herself would popularize in the 1780s. Lustring was a plain woven silk with a glossy finish that was very popular for summer wear, while the fashionable chip hat, made of finely shaved willow or poplar, was to be worn at a jaunty angle.

Mary’s obsession with her outfits might be considered as shallow and frivolous, but this is to misunderstand the power of fashion: she was very attuned to the ways in which clothing could transform her image. Fashion was central to the consumer society of the late eighteenth century. A plethora of shops offered ready-to-wear collections, while there were second-hand clothes stalls for the less well off. Silks, linens, and cottons were more widely available than ever before. Journalism and fashion went hand in hand: new monthly publications such as the Lady’s Magazine included plates and detailed descriptions of the latest styles. Ladies could even hand-colour the black and white engravings and send them off to a mantua-maker with instructions for making up.

Mary loved to remember the tiniest details of the clothes she was wearing on a particular occasion. On the day that she met her future husband in Greenwich she felt that she had never dressed so perfectly to her own satisfaction. Thomas Robinson spent most of the evening simply staring at her. The party dined early and then returned to London, where Robinson’s friend expatiated upon the many good qualities of Mary’s new suitor, speaking of ‘his future expectations from a rich old uncle; of his probable advancement in his profession; and, more than all, of his enthusiastic admiration of me’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Robinson was apparently the heir of a rich tailor called Thomas Harris, who had a large estate in Wales. Hester Darby sensed that the secure marriage she needed for her daughter was within grasp.

As the date set for Mary’s stage debut approached, Robinson was assiduous in his courtship. He knew that it was crucial to win her mother’s approval and did so by his constant attentions and a flow of presents calculated to impress. Hester was especially fond of ‘graveyard’ literature, and she was delighted when Robinson brought her an elegantly bound copy of James Hervey’s lugubrious Meditations among the Tombs of 1746. She was ‘beguiled’ by these attentions and Robinson accordingly ‘became so great a favourite, that he seemed to her the most perfect of existing beings’. He gained more credit when smallpox again threatened the family. This time it was George, Hester’s favourite son, who was dangerously ill. Mary postponed her stage appearance and Robinson was ‘indefatigable in his attentions’ to the sick boy and his anxious mother. Robinson’s conduct convinced Hester that he was ‘“the kindest, the best of mortals!”, the least addicted to worldly follies – and the man, of all others, who she should adore as a son-in-law’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Robinson might have convinced the mother, but he still had some way to go with the daughter. Luck was on his side. When George recovered from the smallpox, Mary fell sick herself. This was a test that would reveal the extent of the suitor’s devotion: would he persist in his courtship despite the threat of death or at the very least disfigurement of her lovely features? He did not waver and duly exerted ‘all his assiduity’ to win Mary’s affections, proving the ‘disinterested’ quality of his fondness. For Mary, the relationship was more fraternal than romantic: ‘he attended with the zeal of a brother; and that zeal made an impression of gratitude upon my heart, which was the source of all my succeeding sorrows’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The combined forces of mother and lover were irresistible. Every kind of persuasion and emotional blackmail was employed to press the suit. Hester urged Mary to promise that if she survived the disease she would marry Robinson. She reiterated the threat made by Mary’s father and even intimated that her daughter’s refusal was proof that she retained affection for the ‘libertine Captain’. Mary was cajoled and bullied, ‘repeatedly urged and hourly reminded’ of her father’s vow. Hester’s only hesitation was the thought of the inevitable separation between mother and daughter that marriage would bring. But the resolute lover overcame this obstacle with his promise of the ultimate sacrifice: he insisted that the bride’s mother should live with them, overseeing the domestic duties. Could Mary really refuse him when he offered her abandoned mother a home?

This was how Mary recollected the courtship when she came to write her memoirs. By making her mother an accomplice in Robinson’s scheme to force her hand, she gave the impression that it was not a marriage of affection on her part. But Hester’s culpability is debatable. Her worries were genuine. Her daughter was headstrong, and Hester was doubtful about a stage career. She was worried about Nicholas and the threat he had issued. Robinson’s motives seemed genuine enough. His was hardly a mercenary choice, as Mary brought no money or prospects. Few men would cherish the idea of living with their mother-in-law during the first years of marriage. It would appear that Robinson was genuinely in love with Mary. Neither was his devotion skin deep. He could well have withdrawn his suit when the ravages of smallpox threatened her beauty. At its worst, this horrific disease rendered its surviving victims disfigured and scarred beyond all recognition. Robinson risked his own health to nurse George and attend Mary. Considered in this light, his commitment could not be doubted.

Mary’s timid acquiescence in the match seems uncharacteristic. She had inherited her father’s intrepidity and her mother’s determination. Every action of her eventful life suggests strength of will and force of personality that little could dampen. But she was weak and vulnerable with illness when she finally agreed to Robinson’s proposal. While she lay on her sickbed, the banns were published during three successive Sunday morning services at the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, in what is now Trafalgar Square.

An unflattering biographical account of the Robinsons, published in 1781, in which the writer claimed that he knew a great deal about the couple’s affairs, claimed that, despite his humble position as a lawyer’s clerk, Thomas presented himself to Mary and Hester as a gentleman of £30,000, sole heir to a Mr Harris of Carmarthenshire, who gave him an allowance of £500 per year and far greater expectations for the future. According to this early biographer, both Mary and her mother jumped at the match.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Doubts may have crept in when Robinson urged mother and daughter to keep the engagement secret. He gave two reasons. One was that he still had three months’ training to serve as an articled clerk and the second that there was another young lady who wished to marry him as soon as he came into independence. Mary had found a small window of opportunity for delay and urged him to postpone the marriage until he came of age. Robinson absolutely refused. Now that she had recovered, with no loss to her looks, Mary still harboured hopes of a stage career. Garrick, wholly unaware that he was in danger of losing his protégée, was agitating for a performance date. Robinson, appealing shrewdly to Hester’s insecurities, invoked strong arguments against the theatre. Nicholas Darby would be horrified by the prospect. Mary’s health would suffer from the ‘fatigues and exertions of the profession’. He also voiced the anti-theatrical prejudice of the age’s moralists when he suggested that Mary would become an object of male desire whose reputation would be irrevocably damaged ‘on a public stage, where all the attractions of the mimic scene would combine to render [her] a fascinating object’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Time was running out for Mary. She now had to decide whether to risk the social embarrassment of pulling out of the marriage even though the banns had been posted or to abandon her hopes of a stage career. With increasing pressure from all angles to choose between the professions of respectable marriage or disreputable acting, she relented: ‘It was now that Mr Robinson and my mother united in persuading me to relinquish my project; and so perpetually, during three days, was I tormented on the subject – so ridiculed for having permitted the bans to be published, and afterwards hesitating to fulfil my contract, that I consented – and was married.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the original manuscript of her Memoirs, Mary proceeded in the next paragraph to describe her feelings as she knelt at the altar on her wedding day. But she later returned to the manuscript and inserted an additional paragraph that creates a compelling picture of herself as little more than a schoolgirl, coerced into marriage out of gratitude and filial obedience. Up until her marriage, she claims, she dressed like a child (though this does not square with the description of her attire on the day she met Robinson for the first time). She insists that she looked ‘so juvenile’ in her appearance that even two years after her wedding shopkeepers would address her as Miss, assuming she was a daughter and not a wife. She even adds that she still retained the manners of a child, playing with her dolls only three months before she became a wife. One senses a certain overegging of the pudding here. The image of the child with her dolls does not equate with that of the young lady being trained by Garrick for the stage and pursued by the ‘libertine Captain’, who was still writing to Mary and following her around in public despite her discovery of the fact that he was already married.

The vicar officiating at the church, Dr Erasmus Saunders, remarked that he had never ‘before performed the office for so young a bride’. The wedding took place on 12 April 1773: Mary Darby became Mary Robinson when she was just under 15

/

. In the Memoirs she presents herself as sexually innocent: ‘the only circumstance which induced me to marry was that of being still permitted to reside with my mother, and to live separate, at least for some time, from my husband’.

(#litres_trial_promo) She chose for her wedding attire the habit of a Quaker – ‘a society to which, in early youth, I was particularly partial’.

(#litres_trial_promo) But when the bride left the church for the wedding breakfast at a friend’s house, she changed her plain dress for something altogether more glamorous. Her gown was muslin, with a matching white sarsenet scarf-cloak; she wore a chip hat with silk ribbons and satin slippers embroidered with silver thread. The change of costume is symbolic of Mary’s struggle to reconcile the contrasting aspects of her character. On the one hand she wanted to be seen as a prudish Quaker, a sexual innocent almost forced into an arranged marriage, but on the other she wanted to be viewed as a beautiful and fashionable bride, decked out in white and silver.

Mary always insisted that her marriage was not a love match. She was deeply romantic and cherished hopes of a soul mate. Robinson was not the man. Of her feelings for her future husband, she wrote, ‘I knew not the sensation of any sentiment beyond that of esteem; love was still a stranger to my bosom.’

(#litres_trial_promo) But according to the Memoirs, it was not another, more dashing suitor that she thought of as she spoke her marriage vows kneeling at the altar of the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. Her thoughts wandered instead to the theatrical career that she was sacrificing, to the glimmer of fame, and the lost opportunity of an independent livelihood.

CHAPTER 3 Wales (#ulink_b982e891-860e-5e38-8291-bef9648225b2)

There is nothing in life so difficult as to acquire the art of making time pass tolerably in the country.

Mary Robinson, The Widow

The wedding party of four set out in a phaeton and a post chaise. They stopped for the night at an inn near Maldenhead. Robinson was accompanied by an old school friend, Hanway Balack, who kept the groom in good cheer whilst the young bride Mary walked in the gardens with her mother, weeping and describing herself as ‘the most wretched of mortals’. She confessed to Hester that although she esteemed Mr Robinson she did not feel for him that ‘warm and powerful union of soul’ which she felt was indispensable for marriage.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Mary was already beginning to regret the clandestine quality of the marriage. During the onward journey to Henley-on-Thames the following day, Hanway had quoted facetiously from Isaac Bickerstaff’s comic opera The Padlock of 1768, then in ‘high celebrity’, which depicted the insecurities of an aged bachelor called Don Diego. His teasing made her painfully aware of the precariousness of her position: Robinson had not told even the friend who was accompanying them on the honeymoon that they were married. Ironically, though, Hanway was to remain a close and loyal friend to Mary throughout her life, long after Robinson had disappeared from it.

(#ulink_a3b7788a-04f4-5ed6-8bb3-0995d3347a5c)

The honeymoon by the river at Henley lasted for ten days. Mary had the painful task of sending Garrick the news that she was married and was therefore relinquishing her stage career. When the couple returned to London, it was to separate residences. Robinson returned to his job in Chancery Lane, while Mary and her mother hired an elegant house in Great Queen Street in fashionable Lincoln’s Inn Fields, backing onto Chancery Lane. Robinson stuck to his insistence that the marriage should be kept secret until he had come of age and finished his articles. Whilst he was busy in chambers, Mary grew bored and found herself a young female companion, who shared her romantic disposition. The girls spent hours wandering in Westminster Abbey, peering at its Gothic windows and listening to the echoes of their footsteps vibrating along the aisles. Mary felt transported back to her childhood in Bristol Minster.

Hester became anxious about her new son-in-law’s continued desire for secrecy. She began to regret the part she had played in promoting the marriage. Then she learnt to her dismay that Robinson had been spinning a web of lies from the very start. He had claimed that his inheritance would fall due when he came of age, but in fact he was already 21. And he had much further to go in his training than he had pretended. Worst of all, Hester discovered the true story of Robinson’s origins. He was not the legitimate heir of his uncle, Thomas Harris, and heir presumptive to a ‘handsome fortune and an estate in South Wales’. He was actually Harris’s illegitimate son – according to one source, the result of a fling with a laundress. Furthermore, with an industrious and ambitious older brother in the picture (whom Robinson had conveniently forgotten to mention), his financial prospects were dim. It was extremely unlikely that he would inherit anything at all from his father. He also owed a lot of money.

Mary, meanwhile, unexpectedly met Garrick walking in a London street. This was the first time she had seen him since informing him by letter of her marriage. She was highly sensible that he had not yielded any return on his protégée and that she had not told him of her defection face to face. After all, she had been trained by the greatest actor of the age and he was not accustomed to having his time wasted by fickle would-be-actresses who changed course at the final hurdle. To his infinite credit and to her utmost relief, he greeted her warmly and congratulated her on her marriage. Mary’s charm and beauty had won him over again. She does not record what she said to him at this meeting. Perhaps she intimated to him, as she did in her Memoirs, that she had been persuaded to marry against her will, and that she deeply regretted the sacrifice of her career. However she managed it – and David Garrick was not the easiest person in the world to sweet-talk – he continued to be a friend and supporter. Mary had a unique talent for maintaining loyal, protective friends, most of whom fell headlong in love with her wit and charm.

Garrick’s knowledge of Mary’s marriage put increasing pressure on Robinson to make the union public. Every day that passed with a disavowal from him put Hester under increasing strain, and Mary’s reputation at greater risk. She could fall pregnant at any time, a plight that Garrick and George Colman the Elder had exploited in their popular comedy of 1766 The Clandestine Marriage. In this play, the lovely young heroine Fanny Sterling is persuaded by her new husband, against her better judgement, to keep her clandestine marriage secret, even though she is heavily pregnant. Despite her condition, she is pursued by many suitors, especially the lecherous aristocrat Lord Ogleby. Mary hints at a similar dilemma in her Memoirs, though it was her mother who was furious with Thomas: ‘The reputation of a darling child, she alleged, was at stake; and though during a few weeks the world might have been kept in ignorance of my marriage, some circumstances that had transpired now rendered an immediate disclosure absolutely necessary.’

(#litres_trial_promo) There is, however, no evidence that Mary was indeed pregnant at this time. Her daughter was born a full year later.