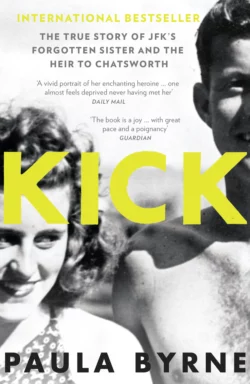

Kick: The True Story of Kick Kennedy, JFK’s Forgotten Sister and the Heir to Chatsworth

Paula Byrne

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 781.54 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The remarkable life of the vivacious, clever – and forgotten – Kennedy sister, who charmed the English aristocracy and was almost erased from her family history.The favourite child of Joe Kennedy and favourite sister of Jack, Kick Kennedy was spirited, vivacious and legendary for her charm. When the Kenndys sailed to Britain in 1938 she was presented as a debutante amid the pre-war social whirl of the British aristocracy. Here she met a shy, tall, handsome man called Billy, and, rebelling against family, faith, and country, soon married him. He was William Cavendish, heir to Chatsworth and the Duke of Devonshire, the most eligible bachelor in England. But their days of married bliss proved short, as war would bring tragedy and loss.Uncovering her spectacular life in full for the first time, Paula Byrne depicts a remarkable woman who bewitched the Churchills, Astors and Mitfords, and yet was almost erased from Kennedy family history.