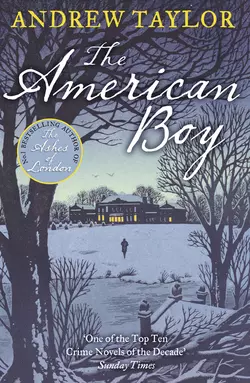

The American Boy

Andrew Taylor

THE NUMBER ONE BESTSELLER AND AWARD-WINNING RICHARD & JUDY BOOK CLUB PICKMurder, lies and betrayal in Regency EnglandEngland 1819. Thomas Shield, a master at a school just outside London, is tutor to a young American boy and the child’s sensitive best friend, Charles Frant. Helplessly drawn to Frant’s beautiful, unhappy mother, Shield becomes entwined in their family’s affairs.When a brutal murder takes place in London’s seedy backstreets, all clues lead to the Frant family, and Shield is tangled in a web of lies, money, sex and death that threatens to tear his new life apart.Soon, it emerges that at the heart of these macabre events lies the strange American boy. What secrets is the young Edgar Allan Poe hiding?

Copyright (#uf6a00c0b-673f-599d-97c9-605af80e752c)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Flamingo 2003

This ebook edition published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Andrew Taylor 2003

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover illustration © Andrew Davidson/The Artworks

Andrew Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008300753

Ebook Edition © December 2012 ISBN: 9780007380985

Version: 2018-09-25

Praise for The American Boy: (#uf6a00c0b-673f-599d-97c9-605af80e752c)

‘An enticing work of fiction … Taylor takes account of both a Georgian formality and a pre-Victorian laxity in social and sexual matters; he is adept at historical recreation, and allows a heady décor to work in his favour by having his mysteries come wrapped around by a creepy London fog or embedded picturesquely in a Gloucestershire snowdrift’

TLS

‘Possibly the best book of the decade is Andrew Taylor’s historical masterpiece, The American Boy. A truly captivating novel, rich with the sounds, smells, and cadences of nineteenth-century England’

Glasgow Herald

‘Long, sumptuous, near-edible account of Regency rogues – wicked bankers, City swindlers, crooked pedagogues and ladies on the make – all joined in the pursuit of the rich, full, sometimes shady life. A plot stuffed with incident and character, with period details impeccably rendered’

Literary Review

‘Taylor spins a magnificent tangential web … The book is full of sharply etched details evoking Dickensian London and is also a love story, shot through with the pain of a penniless and despised lover. This novel has the literary values which should take it to the top of the lists’

Scotland on Sunday

‘It is as if Taylor has used the great master of the bizarre as both starting-and finishing-point, but in between created a period piece with its own unique voice. The result should satisfy those drawn to the fictions of the nineteenth century, or Poe, or indeed to crime writing at its most creative’

Spectator

‘Andrew Taylor has flawlessly created the atmosphere of late-Regency London in The American Boy, with a cast of sharply observed characters in this dark tale of murder and embezzlement’

Sunday Telegraph

‘Madness, murder, misapplied money and macabre marriages are interspersed with coffins, corpses and cancelled codicils … an enjoyable and well-constructed puzzle’

Sunday Times

Dedication (#uf6a00c0b-673f-599d-97c9-605af80e752c)

For Sarah and William.

And, as always, for Caroline.

Epigraph (#uf6a00c0b-673f-599d-97c9-605af80e752c)

I would not, if I could, here or to-day, embody

a record of my later years of unspeakable

misery, and unpardonable crime.

From ‘William Wilson’ by Edgar Allan Poe

Contents

Cover (#u92de31de-e059-5dd9-bc15-b33ffa1553a3)

Title Page (#u42d9b9f4-f560-53f3-ae89-c871de5ceca1)

Copyright

Praise for The American Boy

Dedication

Epigraph

The Wavenhoe Family, 1819

The Narrative of Thomas Shield, 1819–20

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

Chapter Sixty-Seven

Chapter Sixty-Eight

Chapter Sixty-Nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-One

Chapter Seventy-Two

Chapter Seventy-Three

Chapter Seventy-Four

Chapter Seventy-Five

Chapter Seventy-Six

Chapter Seventy-Seven

Chapter Seventy-Eight

Chapter Seventy-Nine

Chapter Eighty

Chapter Eighty-One

Chapter Eighty-Two

Chapter Eighty-Three

Chapter Eighty-Four

Appendix, 1862

A Historical Note on Edgar Allan Poe

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

The Wavenhoe family, 1819 (#uf6a00c0b-673f-599d-97c9-605af80e752c)

N.B. The names underlined are of those members of the family who were alive in September 1819

THE NARRATIVE OF THOMAS SHIELD (#ulink_6c03bf19-a806-5aa8-9a11-804e4c71a8d3)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_4d4293bc-a094-5430-9dd7-5bd1fb3681e2)

WE OWE RESPECT to the living, Voltaire tells us in his Première Lettre sur Oedipe, but to the dead we owe only truth. The truth is that there are days when the world changes, and a man does not notice because his mind is on his own affairs.

I first saw Sophia Frant shortly before midday on Wednesday the 8th of September, 1819. She was leaving the house in Stoke Newington, and for a moment she was framed in the doorway as though in a picture. Something in the shadows of the hall behind her had made her pause, a word spoken, perhaps, or an unexpected movement.

What struck me first were the eyes, which were large and blue. Then other details lodged in my memory like burrs on a coat. She was neither tall nor short, with well-shaped, regular features and a pale complexion. She wore an elaborate cottage bonnet, decorated with flowers. Her dress had a white skirt, puffed sleeves and a pale blue bodice, the latter matching the leather slipper peeping beneath the hem of her skirt. In her left hand she carried a pair of white gloves and a small reticule.

I heard the clatter of the footman leaping down from the box of the carriage, and the rattle as he let down the steps. A stout middle-aged man in black joined the lady on the doorstep and gave her his arm as they strolled towards the carriage. They did not look at me. On either side of the path from the house to the road were miniature shrubberies enclosed by railings. I felt faint, and I held on to one of the uprights of the railings at the front.

‘Indeed, madam,’ the man said, as though continuing a conversation begun in the house, ‘our situation is quite rural and the air is notably healthy.’

The lady glanced at me and smiled. This so surprised me that I failed to bow. The footman opened the door of the carriage. The stout man handed her in.

‘Thank you, sir,’ she murmured. ‘You have been very patient.’

He bowed over her hand. ‘Not at all, madam. Pray give my compliments to Mr Frant.’

I stood there like a booby. The footman closed the door, put up the steps and climbed up to his seat. The lacquered woodwork of the carriage was painted blue and the gilt wheels were so clean they hurt your eyes.

The coachman unwound the reins from the whipstock. He cracked his whip, and the pair of matching bays, as glossy as the coachman’s top hat, jingled down the road towards the High-street. The stout man held up his hand in not so much a wave as a blessing. When he turned back to the house, his gaze flicked towards me.

I let go of the railing and whipped off my hat. ‘Mr Bransby? That is, have I the honour –?’

‘Yes, you have.’ He stared at me with pale blue eyes partly masked by pink, puffy lids. ‘What do you want with me?’

‘My name is Shield, sir. Thomas Shield. My aunt, Mrs Reynolds, wrote to you, and you were kind enough to say –’

‘Yes, yes.’ The Reverend Mr Bransby held out a finger for me to shake. He stared me over, running his eyes from head to toe. ‘You’re not at all like her.’

He led me up the path and through the open door into the panelled hall beyond. From somewhere in the building came the sound of chanting voices. He opened a door on the right and went into a room fitted out as a library, with a Turkey carpet and two windows overlooking the road. He sat down heavily in the chair behind the desk, stretched out his legs and pushed two stubby fingers into his right-hand waistcoat pocket.

‘You look fagged.’

‘I walked from London, sir. It was warm work.’

‘Sit down.’ He took out an ivory snuff-box, helped himself to a pinch and sneezed into a handkerchief spotted with brown stains. ‘So you want a position, hey?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And Mrs Reynolds tells me that there are at least two good reasons why you are entirely unsuitable for any post I might be able to offer you.’

‘If you would permit me, I would endeavour to explain.’

‘Some would say that facts explain themselves. You left your last position without a reference. And, more recently, if I understand your aunt aright, you have been the next best thing to a Bedlamite.’

‘I cannot deny either charge, sir. But there were reasons for my behaviour, and there are reasons why those episodes happened and why they will not happen again.’

‘You have two minutes in which to convince me.’

‘Sir, my father was an apothecary in the town of Rosington. His practice prospered, and one of his patrons was a canon of the cathedral, who presented me to a vacancy at the grammar school. When I left there, I matriculated at Jesus College, Cambridge.’

‘You held a scholarship there?’

‘No, sir. My father assisted me. He knew I had no aptitude for the apothecary’s trade and he intended me eventually to take holy orders. Unfortunately, near the end of my first year, he died of a putrid fever, and his affairs were found to be much embarrassed, so I left the university without taking my degree.’

‘What of your mother?’

‘She had died when I was a lad. But the master of the grammar school, who had known me as a boy, gave me a job as an assistant usher, teaching the younger boys. All went well for a few years, but, alas, he died and his successor did not look so kindly on me.’ I hesitated, for the master had a daughter named Fanny, the memory of whom still brought me pain. ‘We disagreed, sir – that was the long and the short of it. I said foolish things I instantly regretted.’

‘As is usually the case,’ Bransby said.

‘It was then April 1815, and I fell in with a recruiting sergeant.’

He took another pinch of snuff. ‘Doubtless he made you so drunk that you practically snatched the King’s shilling from his hand and went off to fight the monster Bonaparte single-handed. Well, sir, you have given me ample proof that you are a foolish, headstrong young man who has a belligerent nature and cannot hold his liquor. And now shall we come to Bedlam?’

I squeezed the thick brim of my hat until it bent under the pressure. ‘Sir, I was never there in my life.’

He scowled. ‘Mrs Reynolds writes that you were placed under restraint, and lived for a while in the care of a doctor. Whether in Bedlam itself or not is immaterial. How came you to be in such a state?’

‘Many men had the misfortune to be wounded in the late war. It so happened that I was wounded in my mind as well as in my body.’

‘Wounded in the mind? You sound like a school miss with the vapours. Why not speak plainly? Your wits were disordered.’

‘I was ill, sir. Like one with a fever. I acted imprudently.’

‘Imprudent? Good God, is that what you call it? I understand you threw your Waterloo Medal at an officer of the Guards in Rotten-row.’

‘I regret it excessively, sir.’

He sneezed, and his little eyes watered. ‘It is true that your aunt, Mrs Reynolds, was the best housekeeper my parents ever had. As a boy I never had any reason to doubt her veracity or indeed her kindness. But those two facts do not necessarily encourage me to allow a lunatic and a drunkard a position of authority over the boys entrusted to my care.’

‘Sir, I am neither of those things.’

He glared at me. ‘A man, moreover, whose former employers will not speak for him.’

‘But my aunt speaks for me. If you know her, sir, you will know she would not do that lightly.’

For a moment neither of us spoke. Through the open window came the clop of hooves from the road beyond. A fly swam noisily through the heavy air. I was slowly baking, basted in sweat in the oven of my own clothes. My black coat was too heavy for a day like this but it was the only one I had. I wore it buttoned to the throat to conceal the fact that I did not have a shirt beneath.

I stood up. ‘I must detain you no longer, sir.’

‘Be so good as to sit down. I have not concluded this conversation.’ Bransby picked up his eye glasses and twirled them between finger and thumb. ‘I am persuaded to give you a trial.’ He spoke harshly, as if he had in mind a trial in a court of law. ‘I will provide you with your board and lodging for a quarter. I will also advance you a small sum of money so you may dress in a manner appropriate to a junior usher at this establishment. If your conduct is in any way unsatisfactory, you will leave at once. If all goes well, however, at the end of the three months, I may decide to renew the arrangement between us, perhaps on different terms. Do I make myself clear?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Ring the bell there. You will need refreshment before you return to London.’

I stood up again and tugged the rope on the left of the fireplace.

‘Tell me,’ he added, without any change of tone, ‘is Mrs Reynolds dying?’

I felt tears prick my eyelids. I said, ‘She does not confide in me, but she grows weaker daily.’

‘I am sorry to hear it. She has a small annuity, I collect? You must not mind me if I am blunt. It is as well for us to be frank about such matters.’

There is a thin line between frankness and brutality. I never knew on which side of the line Bransby stood. I heard a tap on the door.

‘Enter!’ cried Mr Bransby.

I turned, expecting a servant in answer to the bell. Instead a small, neat boy slipped into the room.

‘Ah, Allan. Good morning.’

‘Good morning, sir.’

He and Bransby shook hands.

‘Make your bow to Mr Shield, Allan,’ Bransby told him. ‘You will be seeing more of him in the weeks to come.’

Allan glanced at me and obeyed. He was a well-made child with large, bright eyes and a high forehead. In his hand was a letter.

‘Are Mr and Mrs Allan quite well?’ Bransby inquired.

‘Yes, sir. My father asked me to present his compliments, and to give you this.’

Bransby took the letter, glanced at the superscription and dropped it on the desk. ‘I trust you will apply yourself with extra force after this long holiday. Idleness does not become you.’

‘No, sir.’

‘Adde quod ingenuas didicisse fideliter artes.’ He prodded the boy in the chest. ‘Continue and construe.’

‘I regret, sir, I cannot.’

Bransby boxed the lad’s ears with casual efficiency. He turned to me. ‘Eh, Mr Shield? I need not ask you to construe, but perhaps you would be so good as to complete the sentence?’

‘Emollit mores nec sinit esse feros. Add that to have studied the liberal arts with assiduity refines one’s manners and does not allow them to be coarse.’

‘You see, Allan? Mr Shield was wont to mind his book. Epistulae Ex Ponto, book the second. He knows his Ovid and so shall you.’

When we were alone, Bransby wiped fragments of snuff from his nostrils with the stained handkerchief. ‘One must always show them who is master, Shield,’ he said. ‘Remember that. Kindness is all very well but it don’t answer in the long run. Take young Edgar Allan, for example. The boy has parts, there is no denying it. But his parents indulge him. I shudder to think where such as he would be without due chastisement. Spare the rod, sir, and spoil the child.’

So it was that, in the space of a few minutes, I found a respectable position, gained a new roof over my head, and encountered for the first time both Mrs Frant and the boy Allan. Though I marked a slight but unfamiliar twang in his accent, I did not then realise that Allan was American.

Nor did I realise that Mrs Frant and Edgar Allan would lead me, step by step, towards the dark heart of a labyrinth, to a place of terrible secrets and the worst of crimes.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_566e611b-b1b1-5de4-a3ee-89ed4607b437)

BEFORE I VENTURE into the labyrinth, let me deal briefly with this matter of my lunacy.

I had not seen my aunt Reynolds since I was a boy at school, yet I asked them to send for her when they put me in gaol because I had no other person in the world who would acknowledge the ties of kinship.

She spoke up for me before the magistrates. One of them had been a soldier, and was inclined to mercy. Since I had indeed thrown the medal before a score of witnesses, and moreover shouted ‘You murdering bastard’ as I did so, there was little doubt in any mind including my own that I was guilty. The Guards officer was a vengeful man, for although the medal had hardly hurt him, his horse had reared and thrown him before the ladies.

So it seemed there was only one road to mercy, and that was by declaring me insane. At the time I had little objection. The magistrates decided that I was the victim of periodic bouts of insanity, during one of which I had assaulted the officer on his black horse. It was a form of lunacy, they agreed, that should yield to treatment. This made it possible for me to be released into the care of my aunt.

She arranged for me to board with Dr Haines, whom she had consulted during my trial. Haines was a humane man who disliked chaining up his patients like dogs and who lived with his own family not far away from them. ‘I hold with Terence,’ the doctor said to me. ‘Homo sum; humani nil a me alienum puto. To be sure, some of the poor fellows have unusual habits which are not always convenient in society, but they are made of the same clay as you or I.’

Most of his patients were madmen and half-wits, some violent, some foolish, all sad; demented, syphilitic, idiotic, prey to strange and fearful delusions, or sweeping from one extreme of their spirits to the other in the folie circulaire. But there were a few like myself, who lived apart from the others and were invited to take our meals with the doctor and his wife in the private part of the house.

‘Give him time and quiet, moderate exercise and a good, wholesome diet,’ Dr Haines told my aunt in my presence, ‘and your nephew will mend.’

At first I doubted him. My dreams were filled with the groans of the dying, with the fear of death, with my own unworthiness. Why should I live? What had I done to deserve it when so many better men were dead? At first, night after night, I woke drenched in sweat, with my pulses racing, and sensed the presence of my cries hanging in the air though their sound had gone. Others in that house cried in the night, so why should not I?

The doctor, however, said it would not do and gave me a dose of laudanum each evening, which calmed my disquiet or at least blunted its edge. Also he made me talk to him, of what I had done and seen. ‘Unwholesome memories,’ he once told me, ‘should be treated like unwholesome food. It is better to purge them than to leave them within.’ I was reluctant to believe him. I clung to my misery because it was all I had. I told him I could not remember; I feigned rage; I wept.

After a week or two, he cunningly worked on my feelings, suggesting that if I were to teach his son and daughters some Latin and a little Greek for half an hour each morning, he would be able to remit a modest proportion of the fees my aunt paid him for my upkeep. For the first week of this instruction, he sat in the parlour reading a book as I made the children con their grammars and chant their declensions. Then he took to leaving me alone with them, at first for a few minutes only, and then for longer.

‘You have a gift for instructing the young,’ the doctor said to me one evening.

‘I show them no mercy. I make them work hard.’

‘You make them wish to please you.’

It was not long after that he declared that he had done all he could for me. My aunt took me to her lodgings in a narrow little street running up to the Strand. Here I perched like an untidy cuckoo, mouth ever open, in her snug nest. I filled her parlour during the day, and slept there at night on a bed they made up on the sofa. During that summer, the reek from the river was well-nigh overwhelming.

I soon realised that my aunt was not well, that I had occasioned a severe increase in her expenditure since my foolish assault with the Waterloo Medal, and that my presence, though she strove to hide it, could not but be a burden to her. I also heard the groans she smothered in the dark hours of the morning, and I saw illness ravage her body like an invading army.

One day, as we drank tea after dinner, my aunt gave me back the Waterloo Medal.

It felt cold and heavy in the palm of my hand. I touched the ribbon with its broad, blood-red stripe between dark blue borders. I tilted my hand and let the medal slide on to the table by the tea caddy. I pushed it towards her.

‘Where did it come from?’

‘The magistrate gave it to me for you,’ she said. ‘The one who was kind, who had served in the Peninsula. He said it was yours, that you had earned it.’

‘I threw it away.’

She shook her head. ‘You threw it at Captain Stanhope.’

‘Does not that amount to the same thing?’

‘No.’ She added, almost pleading, ‘You could be proud of it, Tom. You fought with honour for your King and your country.’

‘There was no damned honour in it,’ I muttered. But I took the medal to please her, and slipped it in my pocket. Then I said – and the one thing led to the other – ‘I must find employment. I cannot be a burden to you any longer.’

At that time jobs of any kind were not easy to find, particularly if one was a discharged lunatic who had left his last teaching post without a reference, who lacked qualifications or influence. But my aunt Reynolds had once kept house for Mr Bransby’s family, and he had a kindness for her. Upon threads of this nature, those chance connections of memory, habit and affection that bind us with fragile and invisible bonds, the happiness of many depends, even their lives.

All this explains why I was ready to take up my position as an under-usher at the Manor House School in the village of Stoke Newington on Monday the 13th of September. On the evening before I left my aunt’s house for the last time, I walked east into the City and on to London Bridge. I stopped there for a while and watched the grey, sluggish water moving between the piers and the craft plying up and down the river. Then, at last, I felt in my trouser pocket and took out the medal. I threw it into the water. I was on the upstream side of the bridge and the little disc twisted and twinkled as it fell, catching the evening sunshine. It slipped neatly into the river, like one going home. It might never have existed.

‘Why did I not do that before?’ I said aloud, and two shopgirls, passing arm in arm, laughed at me.

I laughed back, and they giggled, picked up their skirts and hastened away. They were pretty girls, too, and I felt desire stir within me. One of them was tall and dark, and she reminded me a little of Fanny, my first love. The girls skittered like leaves in the wind and I watched how their bodies swayed beneath thin dresses. As my aunt grows worse, I thought, I grow better, as though I feed upon her distress.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_8d8298b8-16bd-5e05-8734-ab53ec283d16)

ONCE AGAIN, I walked to save money. My box had gone ahead by carrier. I followed the old Roman road to Cambridge, Ermine-street, stretching north from Shoreditch, the bricks and mortar of the city creeping blindly after it like ants following a line of honey.

About a mile south of Stoke Newington, the vehicles on the road came to a noisy standstill. Walking steadily, I passed the uneasy, twitching snake of curricles and gigs, chaises and carts, stagecoaches and wagons, until I drew level with the cause of the obstruction. A shabby little one-horse carriage travelling south had collided with a brewer’s dray returning from London. One of the chaise’s shafts had snapped, and the unfortunate hack which had drawn it was squirming on the ground, still entangled in her harness. The driver was waving his blood-soaked wig at the draymen and bellowing, while around them gathered a steadily expanding crowd of angry travellers and curious bystanders.

Some forty yards away, standing in the queue of vehicles travelling towards London, was a carriage drawn by a pair of matching bays. When I saw it, I felt a pang, curiously like hunger. I had seen the equipage before – outside the Manor House School. The same coachman was on the box, staring at the scene of the accident with a bored expression on his face. The glass was down and a man’s hand rested on the sill.

I stopped and turned back, pretending an interest in the accident, and examined the carriage more closely. As far as I could see, it had only the one occupant, a man whose eyes met mine, then looked away, back to something on his lap. He had a long pale face, with a hint of green in its pallor and fine regular features. His starched collar rose almost to his ears and his neck cloth tumbled in a snowy waterfall from his throat. The fingers on the windowsill moved rhythmically, as though marking time to an inaudible tune. On the forefinger was a great gold signet ring.

A footman came hurrying along the road from the accident, pushing his way through the crowd. He went up to the carriage window. The occupant raised his head.

‘There’s a horse down, sir, the chaise is a wreck and the dray has lost its offside front wheel. They say there’s nothing to do but wait.’

‘Ask that fellow what he’s staring at.’

‘I beg your pardon, sir,’ I said, and my voice sounded thin and reedy in my ears. ‘I stared at no one, but I admired your conveyance. A fine example of the coach-builder’s craft.’

The footman was already looming over me, leaning close. He smelt of onions and porter. ‘Be off with you, then.’ He nudged me with his shoulder and went on in a lower voice, ‘You’ve admired enough, so cheese it.’

I did not move.

The coachman lifted his whip.

Meanwhile, the man in the carriage stared straight at me. He showed neither anger nor interest. There was an impersonal menace in the air, as pungent as gas, even in broad daylight and on a crowded road. Like an itch, I was a minor irritant. The gentleman in the coach had decided to scratch me.

I sketched a bow and strolled away. I did not know the encounter for what it was, an omen.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_e6c6626d-8cfe-5b86-9669-715314fc7d6f)

STOKE NEWINGTON WAS a pretty place, despite its proximity to London. I remember the trees and rooks with affection. The youngest boy in the school was four; the oldest nineteen and so nearly a man that he sported bushy whiskers and was rumoured to have put the baker’s girl with child. The sons of richer and more ambitious parents were prepared for entry at the public schools. Most, however, received all the learning they required at Mr Bransby’s.

‘The parents entrust their sons’ board and lodging to us as well as their tuition,’ Mr Bransby told me. ‘A nutritious diet and a comfortable bed are essential if a boy is to learn. Moreover, if a child lives among gentlefolk, he acquires their ways. We keep strictly to our regimen. It is an essential foundation to sobriety in later life.’

The regimen did not affect Mr Bransby and his household, who lived separately from the rest of the school and were no doubt sufficiently sober already. I was expected to sleep on the boys’ side, as was the only other master who lived at the school, the senior usher.

‘Mr Dansey has been with me for many years,’ Bransby told me when he introduced us. ‘You will find him a scholar of distinction.’

Edward Dansey was probably in his forties, a thin man, dressed in black clothes so old and faded that they were now mottled shades of green and grey. He wore a dusty little wig, usually askew, and had a cast in one eye, which, without being actually oblique, approached nearly to a squint. Both then and later, he was always perfectly civil. His manners were those of a gentleman, despite his shabby clothes. He had the great merit of showing no curiosity about my past history.

When I knew Dansey better I found he had a habit of looking at the world with his chin raised and his lips twisted asymmetrically so that one corner of the mouth curled up and the other curled down; it was as though part of him was smiling and part of him was frowning so one never really knew where one stood with him. The cast in his eye accentuated this ambivalence of expression. The boys called him Janus, perhaps because they believed his mood varied according to the side of his face you saw him from. They were scared of Bransby, who kept a cane in every room of the school so he could flog a boy wherever he was without delay, but they were terrified of Dansey.

On my second Thursday at the school, the manservant padded along to the form room as the boys were streaming out to their two hours of liberty before dinner and requested me to wait on his master.

My immediate fear was that I had somehow displeased Mr Bransby. I went through the door that separated his quarters from the rest of the house, which was like stepping into a different country. Here the air smelt of beeswax and flowers and the walls were freshly papered, the panels freshly painted. Mr Bransby had silence enough to hear the ticking of a clock, a luxury indeed in a house full of boys. I knocked and was told to enter. He was staring out of the window, tapping his fingers on the leather top of his table.

‘Sit down, Shield. I must be the bearer of sad news, I’m afraid.’

I said, ‘My aunt Reynolds?’

Bransby bowed his heavy head. ‘I am truly sorry for it. She was an excellent woman.’

My mind was blank, an empty place filled with fog.

‘She charged the woman with whom she lodged to write to me when she was gone. She died yesterday afternoon.’ He cleared his throat. ‘It appears that it was very sudden at the end, or else they would have sent for you. But there is a letter. Mrs Reynolds directed that it should be given to you after her death.’

The seal was intact. It had been stamped with what looked like the handle of a small spoon. I thought I could make out the imprint of fluting. My aunt had probably used the small silver spoon she kept locked in the caddy with her tea. The wax was streaky, a mixture of rusty orange and dark blue. Economical in all things, she saved the seals of letters sent to her and melted the wax again when she sent a letter of her own.

The mind is an ungovernable creature, particularly under the influence of grief; we cannot always command our own thoughts. I found myself wondering if the spoon would still be there, and whether by rights it was now mine. For an instant the fog cleared and I saw her there, in my mind but as solid as Bransby himself, sitting at the table after dinner, frowning into the caddy as she measured the tea.

‘There will be arrangements to be made,’ Bransby was saying. ‘Mr Dansey will take over your duties for a day or two.’ He sneezed, and then said angrily, ‘I shall advance you a small sum of money to cover any expenses you may have. I suggest you go up to town this afternoon. Well? What do you say?’

I recalled that my sanity was still on trial, and now there was no one to speak for me so I must make shift to speak for myself. I raised my head and said that I was sensible of Mr Bransby’s great kindness. I begged leave to withdraw and prepare for my journey.

A moment later, I went up to my little room in the attic, a green hermitage under the eaves. There at last I wept. I wish I could say my tears were solely for my aunt, the best of women. Alas, they were also for myself. My protector was dead. Now, I told myself, I was truly alone in the world.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_c06233a8-3072-5594-92e1-5f9e749f8f42)

MY AUNT’S DEATH drew me deeper into the labyrinth. It brought me to Mr Rowsell and Mrs Jem.

Her last letter to me was brief and, judging by the handwriting, written in the later stages of her illness. In it, she expressed the hope that we might meet again in that better place beyond the grave and assured me that, if heaven permitted it, she would watch over me. Turning to more practical matters, she informed me that she had left money to defray the expense of her funeral. There was nothing for me to do, for she had decided all the details, even the nature of her memorial, even the mason to cut the letters. Finally, she directed me to wait on her attorney Mr Rowsell at Lincoln’s Inn.

I called at the lawyer’s chambers. Mr Rowsell was a large, red-faced man, bulging in the prison of his clothing as though the blood were bursting to escape from his body. He directed his moon-faced clerk to fetch my aunt’s papers. While we waited he scribbled in his pocketbook. When the clerk returned, Rowsell looked through the will, glancing up at me with bright, bird-like eyes, his manner a curious compound of the curt and the furtive. There were two bequests of five pounds apiece, he told me, one to the maid of all work and the other to the landlady.

‘The residue comes to you, Mr Shield,’ he said. ‘Apart from my bill, of course, which will be a charge on the estate.’

‘There cannot be much.’

‘She drew up a schedule, I believe,’ said Rowsell, reaching into the little deed-box. ‘But do not let your hopes rise too high, young man.’ He took out a sheet of paper, glanced at it and handed it to me. ‘Her goods and chattels, such as they were,’ he continued, staring at me over his spectacles, ‘and a sum of money. A little over a hundred pounds, in all probability. Heaven knows how she managed to put it by on that annuity of hers.’ He stood up and held out his hand. ‘I am pressed for time this morning so I shall not detain you any longer. If you leave your direction with Atkins on your way out, I will write to you when we are in a position to conclude the business.’

A hundred pounds! I walked down to the Strand in a daze similar to intoxication. My steps were unsteady. A hundred pounds!

I went to the house where my aunt had lodged and arranged for the disposal of her possessions. Of the larger items, I kept only the tea caddy with its spoon. The landlady found a friend named Mrs Jem who was willing to buy the furniture. I suspected I would have got a higher price if I had been prepared to look elsewhere, but I did not want the trouble of it. Mrs Jem also bought my aunt’s clothes.

‘Not that they’re worth more than a few shillings,’ she said with a martyred smile; she was a mountainous woman with handsome little features buried in her broad face. ‘More patches and darns than anything else. Still, you won’t want them, will you, so it’s doing you a favour. I’ve only thirty shillings. Will you wait while I fetch the rest of the money?’

‘No.’ I could not bear to stay here any longer, for I wanted to contemplate both my loss and my good fortune in peace and quiet. ‘I will take the thirty shillings and collect the balance later.’

‘As you wish,’ she said. ‘Three Gaunt-court. It’s not a stone’s throw away.’

‘A long throw.’

She gave me a hard stare. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll have the money waiting for you. Six shillings, no more no less. I pay my debts, Mr Shield, and I expect others to pay theirs.’

I could not resist a schoolboy pun. ‘Mrs Jem,’ I said solemnly, ‘you are indeed a pearl of great price.’

‘That’s enough of your impudence,’ she replied. ‘If you’re going, you’d better go.’

The balloon of mirth subsided as I walked away from the house where my aunt had lived. So this was all that a life amounted to – a mound of freshly turned earth in a churchyard, a few pieces of furniture scattered among other people’s rooms, and a handful of clothes that nobody but the poor would want to buy.

There was also the small matter of the money which would come to me. For the first time in my life, I was about to be a man of substance, the absolute master of £103 and a few shillings and pence. The knowledge changed me. Wealth may not bring happiness, but at least it has the power to avert certain causes of sorrow. And it makes a man feel he has a place in the world.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_dda8a305-f275-57a2-8c20-2b056c0c66b9)

WEALTH. THAT BRINGS me to Wavenhoe’s Bank. It was Mr Bransby who first mentioned its name to me. I never went there, never met old Mr Wavenhoe himself until he was on his deathbed, but Wavenhoe’s was the chain that bound us all together, the British and the Americans, the Frants and the Carswalls, Charlie and Edgar. Money plays its own tune, and in our different ways we all found ourselves dancing to it.

Early in October, I applied to Bransby for leave to go up to town. It was on that occasion that he mentioned Wavenhoe’s. I needed to visit London because Mr Rowsell had papers for me to sign, and I wished to collect the few shillings that Mrs Jem owed me. He made no difficulty about my request.

‘Upon one condition, however,’ he went on. ‘I should like you to go on Tuesday. Then you may undertake two errands for me while you are there. Not that you will find them onerous – quite the reverse, I fancy. When you travel up to town, you will take the boy Allan with you and leave him at his parents’ house in Southampton-row. Number thirty-nine. His father writes that his mother desires to have him measured for a suit of clothes against the winter.’

‘Will I collect him on my way back, sir?’

‘No. I understand he is to return later in the evening, and that Mr Allan will make the arrangements. Once you have left him at his father’s house, you may discharge your own business. But afterwards I wish you to call at a house in Russell-square so that you may convey a new pupil to the school. Or rather, he will convey you. The boy’s father tells me he will order the carriage.’ Bransby leaned back in his chair, his body pressing against his waistcoat buttons. ‘His name is Frant.’

I nodded. I remembered the lady who had smiled at me at the gate of the school, and also the man who had nearly set his servants on to me as I walked up Ermine-street. I felt my pulse beating somewhere among the fingers of my clasped hands.

‘Master Frant should suit us very well. His father is one of the partners of Wavenhoe’s Bank. A very sound concern indeed.’

‘How old is the boy, sir?’

‘Ten or eleven. As it happens, this school was commended to Mr Frant by Allan’s father. He is an American of Scottish descent, but resident in London. I understand that he and Mr Frant have conducted business together. Mark this well, Shield: first, a satisfied parent will share his satisfaction with other parents; second, Mr Frant is a gentleman-like man who not only moves in good society but meets wealthy men in the course of his business. Wealthy men have sons who require an education. I would wish you to make a particularly good impression, therefore, on Mr and Mrs Allan and Mr and Mrs Frant.’

‘I shall endeavour to do so, sir.’

Bransby leaned forward across the desk so that he could study me more closely. ‘I am confident that your manner will be everything that is appropriate. But I must confess – and pray do not take this amiss – that some alteration to your dress might be desirable. I advanced you a small sum for clothing, did I not, but perhaps not enough?’

I began to speak: ‘It is unfortunate, sir, that –’

‘And, indeed,’ Bransby rushed on, his colour darkening, ‘you have now been with us for nearly a month and your work has, on the whole, been satisfactory. That being so, from next quarterday I propose to pay you a salary of twelve pounds a year, as well as your board and lodging. It is on the understanding, naturally, that your dress will be appropriate to an usher at this establishment and that your conduct continues to give satisfaction in all respects. In the circumstances, I am minded to advance you perhaps half of your first quarter’s salary so that you may make the necessary purchases.’

Three days later, on Tuesday, 5th October, I travelled up to London. Young Allan sat as far away as possible from me in the coach and replied in monosyllables to the questions I put to him. I delivered the boy into the care of a servant at his parents’ house. I had taken but a few steps along the pavement when I felt a hand on my sleeve. I stopped and turned.

‘Your pardon, sir.’

A tall man in a shabby green coat inclined his trunk forward from the waist. He wore a greasy wig, thick blue spectacles and a spreading beard like the nest of an untidy bird.

‘I am looking – looking for the residence of an acquaintance.’ He had a low, booming voice, the sort that makes glasses vibrate. ‘An American gentleman – a Mr Allan. I wonder whether that might be his house.’

‘It is indeed.’

‘Ah – you are most obliging, sir – so the boy you were with must be his son?’ He swayed as he spoke. ‘A handsome boy.’

I bowed. The man’s face was turned away from me but his breath smelt faintly of spirits and strongly of rotting teeth or an infection of the gums. He was not intoxicated, though, or rather not so it affected his actions. I thought he was perhaps the sort of man who is at his most sober when a little elevated.

‘Mr Shield, sir!’

I turned back to the Allans’ house. The servant had opened the door.

‘There was a message from Mrs Allan, sir. She wishes to keep Master Edgar until tomorrow. Mr Allan’s clerk will bring him back to Stoke Newington in the morning.’

‘Very good,’ I said. ‘I will inform Mr Bransby.’

Without a word of farewell, the man in the green coat walked rapidly in the direction of Holborn. I followed, for my next destination was beyond it, at Lincoln’s Inn. The man glanced over his shoulder, saw me strolling behind him and began to walk more quickly. He knocked against a woman selling baskets and she shrieked abuse at him, which he ignored. He turned into Vernon-row. By the time I reached the corner, there was no sign of him.

I thought perhaps the man in the green coat had mistaken me, or someone behind me, for a creditor. Or he had accelerated his pace for quite a different reason, unconnected with his looking back. I dismissed him from my mind and continued to walk southwards. But the incident lodged itself in my memory, and later I was to be thankful that it had.

At Mr Rowsell’s chambers in Lincoln’s Inn, his clerk had the papers ready for me to sign. But as I was about to take my leave, the lawyer himself came out of his private room and shook me by the hand with unexpected cordiality.

‘I give you joy of your inheritance. You are somewhat changed, Mr Shield, if I may say so without impertinence. And for the better.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘A new coat, I fancy? You have begun to spend your new wealth?’

I smiled at Mr Rowsell, responding to the good humour in his face rather than the words. ‘I have not touched my aunt’s money yet.’

‘What will you do with it?’

‘I shall place it in a bank for a few months. I do not wish to rush into a venture I might later regret.’ I hesitated, then added upon impulse: ‘My employer Mr Bransby happened to mention that Wavenhoe’s is a sound concern.’

‘Wavenhoe’s, eh?’ Rowsell shrugged. ‘They have a good name, it is true, but lately there have been rumours – not that that means anything; the City is a perfect rumour mill, you understand, turning ceaselessly, grinding yesterday’s idle speculations into tomorrow’s facts. Mr Wavenhoe himself is an old man, and they say he delegates much of the day-to-day business of the bank to his partners.’

‘And that is a cause of unease?’

‘Not exactly. But the City does not like change, it may be no more than that. And if Mr Wavenhoe retires, or even dies, his absence may have an effect on confidence in the bank. That is no reflection on the bank itself necessarily, merely on human nature. If you wish, I shall make some inquiries on your behalf.’

I dined at an ordinary among plump lawyers and skinny clerks. My business had taken longer than I had anticipated, and I resolved to postpone my visit to Mrs Jem in Gaunt-court. After dinner, comfortable with beef and beer, I made my way up Southampton-row, passing the Allans’ house. It was a fine autumn afternoon. With my new coat, my new position and my new fortune, I felt I had become a different Tom Shield altogether from the one I had been less than a month before.

As I walked, I observed the passers-by – chiefly the women. My eyes clung to a face beneath a bonnet, a pretty foot peeping beneath the hem of a dress, the curve of a forearm, the swell of a breast, a pair of bright eyes. I heard their laughter, their whispers. I smelt their perfume. Dear God, I was like a boy with his face pressed against the pastry-cook’s window.

One struck me in particular, a tall woman with black hair, a high colour, and a fine full figure; as she climbed into a hackney I thought for an instant that she was Fanny, the girl I had once known, not as she had been then but as she might have become; and for a moment or two a cloud covered my happiness.

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_adaf11c9-aa65-51af-b1be-932fbbf52cdc)

THE FRANTS’ HOUSE was on the south side of Russell-square. I rang the bell and waited. The brass plate sparkled. The paint was new. If a surface could be polished, it had been polished. If it could be scrubbed, it had been scrubbed.

A manservant answered the door, a tall fellow with a fleshy, hook-nosed face. I told him my name and business, and he left me to kick my heels in a big dining room overlooking the square. I walked over to the window and stared down at the square garden. The curtains were striped silk, cream and green, and the green seemed to have been chosen to match exactly the grass outside.

The door opened, and I turned to see Mr Henry Frant. As I did so, I looked for the first time at the wall beside the door, which was opposite the window. A portrait hung there, Mrs Frant to the life, sitting in a park with a tiny boy leaning against her knee and a spaniel stretched on the ground at her feet. In the distance was a prospect of a large stone-built mansion-house.

‘You’re Mr Bransby’s usher, I collect?’ Frant walked quickly towards me, his left hand in his pocket, bringing with him a scent of lavender water. He was the man I had seen at the carriage window in Ermine-street. ‘The boy will be down in a moment.’

There was no sign of recognition on his face. I was too insignificant for him to have remembered me, of course, but it was also possible to believe that my own appearance had changed in the last month. Frant made no move to shake hands; nor was there an offer of refreshment or even a chair. There was an air of excitement about him, of absorption in his own affairs.

‘The boy has milksop tendencies, fostered by his mother,’ he announced. ‘I particularly desire that these traits be eradicated.’

I bowed. In the portrait, Mrs Frant’s small white hand toyed with a brown ringlet that had escaped the confines of her bonnet.

‘He is not to be indulged, do you hear? He has had enough of that already. But now he is grown too old for the softness of women. It is time for him to learn to be a man. Behaving like a blushing maiden will be no good to him when he goes to Westminster. That is one reason why I have determined to send him to Mr Bransby’s.’

‘So he has never been to school before, sir?’

‘He has had tutors at home.’ Frant waved his right hand as though pushing them away, and the great signet ring on his forefinger gleamed as it caught the light from the window. ‘He does well enough at his books. Now it is time for him to learn something equally useful: how to deal with his fellows. But I will not detain you any longer. Pray give my compliments to Mr Bransby.’

Before I could manage even another bow, Frant was out of the room, the door snapping shut behind him. I envied him: here was a man who had everything the gods could bestow including an air of breeding and consequence that sat naturally upon him, as though he were its rightful possessor. Even now, God help me, part of me envies him as he was then.

I waited another moment, studying the portrait. My interest, I told myself, was both pure and objective. I admired the painting as I might a beautiful statue or a line of poetry that spoke with both elegance and force to the heart. The brushwork was particularly fine, and the skin was exquisitely lifelike. Such beauty was refreshing, too, like a drink to a thirsty traveller. There was, therefore, no reason why I should not study it as much as I wished.

Ah, you will say, you were falling in love with Sophia Frant. But that is romantic nonsense. If you want plain speaking, I will give it you as I gave it to myself on that fateful day: leaving artistic considerations aside, I disliked her because she had so much I lacked in the way of wealth and the world’s esteem; and I also disliked her because I desired her, as I did almost any pretty woman I saw, and knew she could never be mine.

I heard footsteps outside the door and a high voice speaking indistinctly but loudly. I moved away and feigned an intense interest in the ormolu clock upon the mantel-shelf. The door opened and a boy rushed into the room, followed by a small, plain woman, dressed in black and with a wart on the side of her chin. What struck me immediately was that there was a remarkable resemblance between young Frant and Edgar Allan, the American boy. With their lofty brows, their bright eyes and their delicate features, they might almost have been brothers. Then I noticed the boy’s attire.

‘Good afternoon, sir,’ he said. ‘I am Charles Augustus Frant.’

I shook the offered hand. ‘And I am Mr Shield.’

‘And this is Mrs Kerridge, my – one of the servants,’ the boy rushed on. ‘There was no need for her to come down with me, but she insisted.’

I nodded to her and she inclined her head. ‘I wished to ask if Master Charles’s box had arrived at the school yet, sir.’

‘I’m afraid I do not know. But I’m sure its absence would have been marked.’

‘And my mistress desired me to say that Master Charles feels the cold. When the weather begins to turn, perhaps a flannel undershirt next to the skin might be advisable.’

The boy snorted. I nodded gravely. My mind was on the lad’s clothes, though not in a way that Mrs Kerridge or indeed Mrs Frant would have liked. Whether at his own request or at his mother’s whim, Master Charles was wearing a beautifully cut olive greatcoat with black frogs. He carried under his arm a hat from which depended a long and handsome tassel; he clutched a cane in his left hand.

‘They’re bringing the carriage round, sir,’ Mrs Kerridge said, ‘and Master Charles’s valise is in the hall. Would you like anything before you go?’

The boy hopped from one leg to another.

‘Thank you, no,’ I said.

‘There’s the carriage.’ He ran over to the window. ‘Yes, it is ours.’

Mrs Kerridge looked up at me, squeezing her face to a frown. ‘Poor lamb,’ she murmured in a tone too low for him to hear. ‘Never been away from home before.’

I nodded, and smiled in a way I hoped the woman would find reassuring. When we opened the door, a footman was waiting by the front door and a black pageboy, not much older than Charles himself, hovered over the valise. Charles Frant, smiling graciously at his father’s servants, marched down the steps with a dignity befitting the Horse Guards, a dignity only slightly marred by the way he skipped up into the carriage. Mrs Kerridge and I followed more slowly, walking behind like a pair of acolytes.

‘He is very young for his age, sir,’ Mrs Kerridge muttered.

I smiled down at her. ‘He’s a handsome boy.’

‘Takes after his mother.’

‘Is she not here to say goodbye to him?’

‘She’s away nursing her uncle.’ Mrs Kerridge grimaced. ‘The poor gentleman’s dying, and he ain’t going easy. Otherwise Madam would be here. Will he be all right, sir? Boys can be cruel little varmints. He don’t realise. He don’t know many boys.’

‘It may not be easy at first. But most boys find there is much to enjoy at school as well. Once they are used to it.’

‘His mama frets about him.’

‘It often happens that an event is more distressing in anticipation than it is in actuality. You must endeavour to –’

I broke off, realising that Mrs Kerridge was no longer looking at me. She had been distracted by the sight of a carriage whirling into the square from Montague-street. It was an elegant light chariot, painted green and gold, and drawn by a pair of chestnuts. The coachman slipped between two carts and brought the equipage to a standstill behind our own, the wheels neatly aligned within a couple of inches of the kerb. He sat back on the box with the air of a man well pleased with himself.

‘Oh Lord,’ muttered Mrs Kerridge, but she was smiling.

The glass slid down. I glimpsed a pale face and a mass of auburn curls partly concealed by a large hat adorned with grogram.

‘Kerridge!’ the girl called. ‘Kerridge, dearest. Am I in time? Where’s Charlie?’

Charles jumped out of the Frants’ carriage and ran along the pavement. ‘Do you like this rig, Cousin Flora? Mighty fine, ain’t it?’

‘You look very handsome,’ she said. ‘Quite the military man.’

He held his face up for her to kiss him. She leaned down and I had a better view of her. She was older than I had thought – a young woman; not a girl. Mrs Kerridge came forward to be kissed in her turn. Then the young woman’s eyes turned to me.

‘And who is this? Will you introduce us, Charlie?’

He coloured. ‘I beg your pardon. Cousin Flora, allow me to name Mr Shield, an usher at Mr Bransby’s – my school, you know.’ He swallowed, and then gabbled, ‘Mr Shield, my cousin Miss Carswall.’

I bowed. With great condescension, Miss Carswall held out her hand. It was a little hand that seemed to vanish within my own. She wore lilac-coloured gloves, I recall, which matched the pelisse she wore over her white muslin dress.

‘You were about to convey my cousin to school, no doubt? I shall not detain you long, sir. I merely wished to say farewell to him, and to give him this.’

She undid the drawstring of her reticule and took out a small purse which she handed to him. ‘Put it somewhere safe, Charlie. You may wish to treat your friends.’ She bent down, kissed the top of his head, and gave him a little push away from her. ‘Your mama sends her best love, by the by. I saw her for a moment at Uncle George’s.’

For an instant the boy’s face became perfectly blank, drained of the fun and excitement.

Miss Carswall patted his shoulder. ‘She cannot leave him, not at this moment.’ She looked over the boy to Mrs Kerridge and myself. ‘I must not delay you any longer. Kerridge, dearest, may I drink tea with you before I go? It would be like old times.’

‘Mr Frant is within, miss.’

‘Oh.’ The young lady gave a little laugh, and a look of understanding passed between her and Mrs Kerridge. ‘Good God, I had almost forgot. I am promised to Emma Trenton. Another time, perhaps, and we shall have a good old prose together.’

Miss Carswall’s departure was the signal for ours. I followed Charlie into the Frants’ carriage. A moment later we turned into Southampton-row. The boy huddled into the corner and turned his head to stare out of the far window. The tassel on that ridiculous hat swayed and bounced behind him.

Flora Carswall could never have been called beautiful, unlike Mrs Frant. But she had a quality of ripeness about her, like fruit waiting to be plucked, demanding to be eaten.

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_bec66261-4b11-5678-8451-65d400f50e80)

I FOUND IT difficult to sleep that night. My mind was possessed with a strange excitement that would not let me rest. I felt that during the day I had crossed from one part of my life into another, as though its events formed a river between two countries. I lay in my narrow bed, my body twitching and turning and sighing. I measured the passage of time by the striking of clocks. At last, a little after half-past one, my restlessness drove me from the warmth of my bed to smoke a pipe.

Mr Bransby held that snuff was the only form of tobacco acceptable to a gentleman so Dansey and I found it necessary to smoke outside. But I knew where the key to the side door was kept. A moment later I walked down the lawn, my footsteps making no noise on the wet grass. There were a few clouds but the stars were bright enough for me to see my way. To the south was a faint lessening of the darkness, a yellow haze, the false dawn of London by night, the city which never went to sleep. Beneath the trees it was completely dark. I smoked in the shelter of a copper beech, leaning against the trunk. Leaves stirred above my head. Tiny crackles and rustles near my feet hinted at the passage of small, secretive animals.

Then came another sound, a screech so sharp and hard and unexpected that I jerked myself away from the tree and almost choked on the smoke in my mouth. It came from the direction of the house. There was another, quieter noise, the scrape of metal against metal, followed by a smothered laugh.

I crouched and knocked out the pipe on the soft, damp earth. I moved forward, my feet making little sound on the leaf mould and the husks of last year’s beech nuts. By now my eyes had grown accustomed to the near darkness. Something white was hanging from an attic window in the boys’ wing. The room behind it was in darkness. I veered aside into the slightly deeper darkness running along the line of a hedge.

The attic was not in the same wing of the house as my own and Dansey’s. Most of the boys slept in dormitories, with ten or twelve of them crammed together in one of the larger rooms below. But in this part of the attic storey, two or three boys might share one of the smaller rooms if their parents were willing to pay extra for the privilege.

Once again, I heard the gasp of laughter, snuffed out almost as soon as it began. Suddenly, and with an anger so sharp that it stabbed me like a knife, I knew what I had seen. I went quickly into the house, lit my candle and made my way to the stairs leading to the boys’ attics. I found myself in a narrow corridor. By the light of the candle I saw five doors, all closed.

I tried the doors in turn until I found the one I wanted. I saw three truckle beds in the wavering glow of the candle flame. From two of them came the sound of loud, regular snoring. From the third came the broken breathing of a person trying not to cry. The window was closed.

‘Which boys are in this room?’ I demanded, not troubling to lower my voice.

One boy stopped snoring. To compensate, the other snored with redoubled force. The third boy, the one who had been trying not to cry, became completely silent.

I pulled the blankets from the nearest bed and tossed them on the floor. Its occupant continued to snore. I held the candle close to his face.

‘Quird,’ I said. ‘You will wait behind after morning school.’

I stripped the covers from the next bed. Another boy stared up at me, making no pretence at sleep.

‘You will accompany him, Morley.’

My foot caught on something on the floor. I bent down and made out a length of rope like a basking snake, most of it pushed beneath Morley’s bed.

With a grunt of anger, I threw off the covers from the third bed. There was Charlie Frant, his nightshirt rucked up above his waist and a handkerchief tied round his mouth.

I swore. I placed the candle on the windowsill, lifted the boy up and pulled down the nightshirt. He was trembling uncontrollably. I untied the handkerchief. The lad spat out a rag they had pushed inside his mouth. He retched once. Then, without a word, he fell back on the bed, turned away from me and buried his head in the pillow and began to sob.

Morley and Quird had hung him out of the window. The older boys had lashed his ankles round the central mullion to prevent him from breaking his neck on the gravel walk below.

‘I will see you tomorrow,’ I heard myself saying to them. ‘At present, I cannot see any reason why I should not flog you twice a day and every day until Christmas.’

I wondered whether I should remove young Frant from his tormentors, but what would I do with him? The boy had to sleep somewhere. But the nub of the matter was that, sooner or later, by day or by night, young Frant would have to face up to Quird and Morley. Punishing them was one thing; but trying to shield him was another.

I went back to my own room. I did not sleep until dawn. When I did, it seemed only moments before the bell rang for another day of hearing little savages construe Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

CHAPTER NINE (#ulink_0d1375b0-3ad6-5b3b-a178-f59fa76527d3)

I WATCHED CHARLIE Frant in morning school, both before breakfast and after it. The boy sat by himself at the back of the room. I doubted if he turned a page of his book or even saw what was written on the one in front of him. His coat was now too bedraggled to have a military air. He had tear tracks on his cheeks, and his nostrils were caked with blood and mucus. Smears on the sleeve showed where he had wiped his nose.

At breakfast, I told Dansey what had happened in the night. The older man shrugged.

‘If the boy goes to Westminster School, he’ll get far worse than that.’

‘But we cannot let it pass.’

‘We cannot prevent it.’

‘If the older boys would but exert some authority over the younger ones –’

Dansey shook his head. ‘This is not a public school. We do not have a tradition of self-governance by the boys.’

‘If I went to Mr Bransby, might he not expel them or at least discipline them – Quird and Morley, I mean?’

‘You forget, my dear Shield: the true aim of this establishment is not an educational one. Considered properly, it is nothing but a machine for making money. That is why Mr Bransby has sunk his capital in it. That is why you and I are sitting here drinking weak coffee at Mr Bransby’s expense. Both Quird and Morley have younger brothers.’ Dansey’s lips twisted into their Janus-like frowning smile. ‘Their fathers pay their bills.’

‘Then is there nothing to be done?’

‘You can beat the wretched boys so soundly that you reduce their ability to persecute their unfortunate friend. At least I can be of assistance in that respect.’

At eleven o’clock, after the second session of morning school, I flogged Morley and Quird harder than I had ever flogged a boy before. They did not enjoy it but they did not complain. Custom blunts even pain.

Later, I caught sight of Charlie Frant in the playground. Half a dozen boys had grouped around him in a ragged circle. They tossed the hat from one to the other, encouraging him to make ineffectual grabs for it. The hat had lost its tassel. Some wag had contrived to pin it on the back of the olive-green coat.

‘Donkey,’ they chanted. ‘Who’s a little donkey? Bray, bray, bray.’

When lessons resumed after dinner, Frant was not at his desk. He had hidden himself away to lick his wounds. I decided that if Lord Nelson could turn a blind eye to matters he did not wish to see, then so could I. I did not, however, turn a blind eye to either Quird or Morley. Their work, never distinguished, withered under the unremitting attention that I bestowed upon it. I gave them both the imposition of copying out ten pages of the geography textbook by the following morning.

Towards the end of afternoon school, the manservant came from Mr Bransby’s part of the house and desired Dansey and myself to wait upon his master without delay. We found him in his study, pacing up and down behind his desk, his face dark with rage and a trail of spilt snuff cascading down his waistcoat.

‘Here’s a fine to-do,’ he began without any preamble, before I had even closed the door. ‘That wretched boy Frant.’

‘He has absconded?’ Dansey said.

Bransby snorted.

‘Not worse, I hope?’ There was the barest trace of amusement in Dansey’s voice, like an intellectual whisper pitched too low for Mr Bransby’s range of comprehension. ‘He has – harmed himself?’

Bransby shook his head. ‘It appears that he strolled away, as cool as a cucumber, after the boys’ dinner. He walked a little way and then found a carrier willing to give him a ride to Holborn. I understand that Mrs Frant is away from home but the servants at once sent word to Mr Frant.’ He waved a letter as though trying to swat a fly. ‘His stable boy brought this.’

He took another turn in silence up and down the room. We watched him warily.

‘It is most vexing,’ he continued at length, glowering at each of us in turn. ‘That it should concern Mr Frant – the very man we should study to please in every particular.’

‘Has he settled on withdrawing the boy?’ Dansey asked.

‘We are spared that, at least. Mr Frant wishes his son to return to us. But he demands that the boy be suitably chastised for his transgression so that he apprehends that the discipline of the school is firmly allied to paternal authority. Mr Frant desires me to send an under-master to collect his son, and he proposes that the under-master should flog the boy in his, that is to say Mr Frant’s, presence and in the boy’s own home. He suggests that in this way the boy will realise that he has no choice but to knuckle down to the discipline of the school and that by this he will learn a valuable lesson that will stand him in good stead in his later life.’ Bransby’s heavy-lidded eyes swung towards me. ‘No doubt you were about to volunteer, Shield. Indeed, my choice would have fallen on you in any case. You are a younger man than Mr Dansey, and therefore have the stronger right arm. There is also the fact that I can spare you more easily than I can Mr Dansey.’

‘Sir,’ I began, ‘is not such a course –?’

Dansey, standing behind me and to the left, stabbed his finger into my back. ‘Such a course of action is indeed a trifle unusual,’ he interrupted smoothly, ‘but in the circumstances I have no doubt that it will prove efficacious. Mr Frant’s paternal concern is laudable.’

Bransby nodded. ‘Quite so.’ He glanced at me. ‘The stable boy has ridden back to town with my answer. The chaise from the inn will be here in about half an hour. Be so good as to discuss with Mr Dansey how he should best discharge your evening duties as well as his own.’

‘When will it be convenient for me to wait upon Mr Frant?’

‘As soon as possible. You will find him now at Russell-square.’

A moment later, Dansey and I went through the door from the private part of the house to the school. A crowd of inky boys scattered as though we had the plague.

‘Did you ever hear of anything so unfeeling?’ I burst out, keeping my voice low for fear of eavesdroppers. ‘It is barbaric.’

‘Are you alluding to the behaviour of Mr Frant or the behaviour of Mr Bransby?’

‘I – I meant Mr Frant. He wishes to make a spectacle of his own son.’

‘He is entirely within his rights to do so, is he not? You would not dispute a father’s right to exercise authority over his child, I take it? Whether directly or in a delegated form is surely immaterial.’

‘Of course not. By the by, I must thank you for your timely interruption. I own I was becoming a little heated.’

‘Mr Frant and his bank could purchase this entire establishment many times over,’ Dansey observed. ‘And purchase Mr Quird and Mr Morley as well, for that matter. Mr Frant is a fashionable man, too, who moves in the best circles. If it is at all possible, Mr Bransby will do all in his power to indulge him. It is not to be wondered at.’

‘But it is hardly just. It is the boy’s tormentors who deserve chastisement.’

‘There is little point in railing against circumstances one cannot change. And remember that, by acting as Mr Bransby’s agent in this, you may to some degree be able to palliate the severity of the punishment.’

We stopped at the foot of the stairs, Dansey about to go about his duties, I to fetch my hat, gloves and stick from my room. For a moment we looked at each other. Men are strange animals, myself included, riddled with inconsistencies. Now, in that moment at the foot of the stairs, the silence became almost oppressive with the weight of things unsaid. Then Dansey nodded, I bowed, and we went our separate ways.

CHAPTER TEN (#ulink_140ecd4f-5ff5-5340-8707-c7ca61e18c71)

I COME NOW to an episode of great significance for this history, to the introduction of the Americans.

Providence in the form of Mr Bransby decreed I should witness a scene of comings and goings in Russell-square. A man believes in Providence because to do otherwise would force him to see his life as an arbitrary affair, conducted by the freakish rules of chance, no more under his control than a roll of the dice or the composition of a hand of cards. So let us by all means believe in Providence. Providence arranged matters so that I should call at Mr Frant’s on the same afternoon as the Americans arrived.

The shabby little chaise from the inn brought me to London. The vehicle creaked and groaned as though afflicted with arthritis. The seat was lumpy, the leather torn and stained. The interior smelt of old tobacco and unwashed bodies and vinegar. The ostler who was driving me swore at the horse, a steady stream of obscenity punctuated by the snapping of the whip. As we drove, the daylight drained away from the afternoon. By the time we reached Russell-square, the sky was heavy with dark, swirling clouds the colour of smudged ink.

My knock was answered by a footman, who showed me into the dining room to wait. Because of the weather and the lateness of the afternoon, the room was in near darkness. I turned my back on the portrait. Rain was now falling on the square, fat drops of water that smacked on to the roadway and tapped like drumbeats on the roof of the carriages. I heard voices in the hall, and the slam of a door.

A moment later the footman returned. ‘Mr Frant will see you now,’ he said, and jerked his head for me to follow him.

He led me across the marble chequerboard of the hall to a door which opened as we approached. The butler emerged.

‘You are to desire Master Charles to step this way,’ he told the footman.

The footman strode away. The butler took me into a small and square apartment, furnished as a book-room. Henry Frant was seated at a bureau, pen in hand, and did not look up. The shutters were up and candles burned in sconces above the fireplace and in a candelabrum on a table by the window.

The nib scratched on the paper. The candlelight glinted on Frant’s signet ring and the touches of silver in his hair. At length he sat back, re-read what he had written, sanded the paper, and folded it. As he opened one of the drawers of the bureau, I noticed that he was missing the top joints of the forefinger on his left hand, a blemish on his perfection which pleased me. At least, I thought, I have something that you have not. He slipped the paper in the drawer.

‘Open the cupboard on the left of the fireplace,’ he said without looking at me. ‘Below the shelves. You will find a stick in the right-hand corner.’

I obeyed him. It was a walking-stick, a stout malacca cane with a silver handle and a brass-shod point.

‘Twelve good hard strokes, I think,’ Mr Frant observed. He indicated a low stool with his pen. ‘Mount him over that, with his face towards me.’

‘Sir, the stick is too heavy for the purpose.’

‘You will find it answers admirably. Use it with the full force of your arm. I desire to teach the boy a lesson.’

‘Two older boys set on him at school,’ I said. ‘That is why he ran away.’

‘He ran away because he is weak. I do not say he is a coward, not yet; but he might become one if indulged. Pray make it clear to Mr Bransby that I do not expect the school to indulge his weaknesses any more than I do.’ There was a knock on the door. He raised his voice. ‘Come in.’

The butler opened the door. The boy edged into the room.

‘Sir,’ he began in a small, high voice. ‘I hope I find you in good health, and –’

‘Be silent,’ Frant said. ‘Wait until you are spoken to.’

The butler stood in the doorway, as if waiting for orders. In the hall behind were the footman and the little Negro pageboy. I glimpsed Mrs Kerridge on the stairs.

Frant looked beyond his son and saw the servants. ‘Well?’ he snapped. ‘What are you gaping at? Do you not have work to do? Be off with you.’

At that moment the doorbell rang. The servants jerked towards it, as though attached to the sound by a set of strings. There was another ring, followed immediately by knocking. The footman glanced over his shoulder at the butler, who looked at Mr Frant, who squeezed his lips together in a tight, horizontal line and nodded. The footman scurried to the front door.

Mrs Frant slipped into the hall before the door was more than a foot or two ajar. A maid followed her in. Mrs Frant’s colour was high as if she had been running, and she clutched her cloak to her throat. She darted across the squares of marble to the door of the book-room, where she stopped suddenly on the threshold, as though confronted by an invisible barrier. For a moment nobody spoke. Mrs Frant’s grey travelling cloak slipped from her shoulders to the floor.

‘Madam,’ Frant said, standing up and bowing. ‘I’m rejoiced to see you.’

Mrs Frant looked up at her husband but said nothing. He was a tall, broad man and beside him she looked as defenceless as a child.

‘Allow me to name Mr Shield, one of Mr Bransby’s under-masters.’

I bowed; she inclined her head.

Frant said, ‘You are come from Albemarle-street? I hope I should not infer from this unexpected visit that Mr Wavenhoe has taken a turn for the worse?’

She glanced wildly at him. ‘No – that is to say, yes, in that he is no worse and may even be slightly better.’

‘What gratifying intelligence. Now, Mrs Frant, I do not know whether you are aware that your son has chosen to pay us an unauthorised visit from his school. He is about to pay the penalty for this, and then Mr Shield will convey him back to Stoke Newington.’

Mrs Frant glanced at me, and saw the malacca cane in my hand. I looked at the boy, who was shaking like a shirt on a washing line.

‘May I speak with you, sir?’ she said. ‘A word in private?’

‘I am afraid that at present I am not at leisure. Pray allow me to wait on you in the drawing room when Mr Shield and Charles have left us.’

‘No,’ Mrs Frant said so softly that I could hardly hear her. ‘I must ask you –’

There came another ring on the doorbell.

‘Confound it,’ Frant said. ‘Mr Shield, would you excuse us for a moment? Frederick will show you into the dining room. Close the door of this room, Loomis. Then see who that is. Neither Mrs Frant nor I are at home.’

I propped the cane against a bookcase and went into the hall. Mrs Kerridge moved towards the back of the house, shooing the maid before her. Loomis pulled open the front door. I glanced over his shoulder.

For an instant, I thought it was much later than it really was. Rain was now falling heavily over the square from a sky as black as coal. Through the doorway came the smell of freshly watered dust, and the hissing and pattering of the rain. The brief illusion of night was reinforced by an enormous umbrella stretching across the width of the doorway. Below it I glimpsed a small, grey man in a snuff-coloured coat.

‘My name is Mr Noak,’ announced the newcomer in a hard, nasal voice. ‘Pray inform Mr Frant that I am here.’

‘Mr Frant is not at home, sir. If you would like to leave your –’

‘Nonsense, man. They told me at his place of business he was here. He is expecting me.’