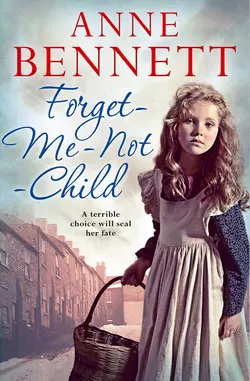

Forget-Me-Not Child

Anne Bennett

A story of struggle and hardship and one girl’s battle for survival from the best-selling author of If You Were the Only Girl and Another Man’s Child.Angela McCluskey comes to Birmingham from Ireland with her family as a young girl to escape the terrible poverty in her homeland. But the dream of a better life is dashed as bad fortune dogs the family.When Angela marries her childhood sweetheart, she has hopes of a brighter future, which are dashed when her husband is called up to fight in the Great War. Tragedy strikes and Angela is left to rear her frail daughter on her own, though the worst is yet to come when Angela suffers another terrible misfortune.Pregnant and destitute and already with one mouth to feed that she can ill afford, there is nowhere left to turn. What destiny awaits Angela and her unborn child? Caught between the devil and the deep blue sea, will Angela forever be punished for the choices that she makes?

Copyright (#ulink_4d84b963-e51b-559a-bb95-7e9367ab4a09)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Anne Bennett 2017

Anne Bennett asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008162313

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780008162320

Version: 2017-09-08

Dedication (#ulink_4c4b73a7-5b69-5864-8c23-0397acfc90b8)

I dedicate this, my 20th book, to my family for their love and encouragement over the years. I love and appreciate you all greatly.

Contents

Cover (#uc929979e-55c5-586b-b31a-98f5d6c2a5fd)

Title Page (#uc782161c-a9fb-5fc1-89ea-e9293897abb5)

Copyright (#u5b26dbc9-886e-5251-9cc0-46677c9a7b4f)

Dedication (#ubebf0cdc-ce55-5b17-aaca-df59d9831f18)

Chapter One (#u46556fcf-c94b-50ef-a461-787f86efad6c)

Chapter Two (#ue649c7f4-0163-51c6-80ab-8e89e355a78f)

Chapter Three (#u26a9ab91-727b-5e51-b9c1-fbdf3b03c25a)

Chapter Four (#u1c4a2e2f-bb48-5356-bcbb-67d245b9ba5a)

Chapter Five (#u3878607b-52ee-5d0d-ab79-e6e2aaca932b)

Chapter Six (#u84f30c9b-8327-5c94-9100-2310e435e600)

Chapter Seven (#u453009c0-b663-5330-a303-8a6d8765e467)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_14d2cb92-188b-5d68-840a-1ae1e1a53a67)

Angela could remember little of her earlier life when the McClusky family lived in Donegal in Northern Ireland. As she grew she had understood that her name was not McClusky but was Kennedy, and she was the youngest daughter of Connie and Padraig Kennedy, and that Mary and Matt McClusky were not her real parents at all, though she called them Mammy and Daddy. She also learned that she had once had four older siblings all at school and so when Minnie the eldest contracted TB and Angela’s mother realized it was rife in the school, she asked Mary McClusky, who was a great friend of hers, to care for Angela, then just eighteen months old, in an effort to keep her safe. Mary had not hesitated and Angela lived in the McClusky home, petted and feted by the five McClusky boys who had never had a girl in the family before.

However, before Angela was two years old she was an orphan; for her parents succumbed to TB too as they watched their children die one by one. Mary was distraught at the loss of her dear friend and all those poor young children. And Padraig too, for he was a fine strapping man and well able, anyone would have thought, to fight off any illness.

‘Ah, but maybe he hadn’t the will to fight,’ Matt said. ‘He’d watched his children all die and then his wife had gone as well before he developed it. What was left for him if he had recovered? I imagine he didn’t bother fighting it.’

Whatever the way of it, there was a spate of funerals and though Angela attended none of them she was aware of a sadness in the McClusky family without understanding it.

Eventually Mary had to rouse herself for she had a family to see to, including little motherless Angela, and Matt had a farm to run. Mary did wonder if there was some long-lost relative who would look after Angela, but after the last funeral it was apparent there wasn’t and Mary decided that she would stay with them. She knew there would be no opposition from Matt who had by then grown extremely fond of her, as they all had, and he just nodded when Mary said it was the very least she could do for her friend. Matt too had been badly shaken by the deaths of the entire Kennedy family and was well aware that a similar tragedy could have happened to his family just as easily. This time they had got through unscathed and he readily agreed that Angela should continue to live with them and grow up as their daughter.

‘Angela will be your new little sister,’ Mary told her sons. Not one of them made any objection but the happiest of them all was her youngest, Barry. At five years old, he was three years older than Angela and she was petite for her age with white-blonde curls and big blue eyes that reminded him of a little doll. She was better than any doll though for she seemed to have happiness running through her, her ready smile lit up her whole face and her laugh was so infectious all the McClusky boys would nearly jump through hoops to amuse her. ‘I will be the best brother I know how to be,’ Barry said earnestly. ‘I was already fed up of being the youngest.’

Mary laughed and tousled Barry’s hair. ‘I’m sure you will, son,’ she said, ‘and she will love you dearly.’

And Angela did. Between her and Barry there was a special closeness though she loved all the boys she thought of as brothers and all were kind and gentle with her.

However the farm didn’t thrive. A blight damaged most of the potato crop, and heavy and sustained storms left them with barely half of the hay they would need for the winter, meaning they would have to buy the hay needed from elsewhere, while many cabbages, turnips and swedes were lost to the torrential and ferocious rains that eventually flooded the hen house, resulting in many hens also being lost. That first bad winter they just about managed although empty bellies were often the order of the day and later Barry told Angela she was lucky not to remember those times.

Everyone looked forward to the spring after the second bad winter. Matt and his sons knew that if the spring was going to be a fine one nothing would go awry and with tightened belts they might survive. Matt had a constant frown between his eyes because the weather wasn’t good. ‘Surely this year will be better than last,’ Mary said.

Matt’s lips tightened. ‘We’ll see,’ he said grimly. ‘For if it’s not a great deal better we will sink.’

In the early spring of that year a cow died giving birth and the female calf died, a fox got into the hen house and killed most of the hens, and one of the lambs scattered on the hillside was savaged by a dog and had to be put out of his misery. As their finances were on a keen knife edge these things were major blows. Matt knew he would have to leave the farm where he had lived all his life and his father before and his father. That thought was more than upsetting, it was devastating, but he had to face facts. One evening in late March after Angela and Barry had gone to bed and the dinner pots and plates had been put away, Matt and Mary faced their four eldest sons across the table and told them they didn’t think they could survive another year.

There was a gasp from Sean and Gerry, but Finbarr and Colm, who helped their father on the farm, were not totally surprised. They knew as well as anyone how badly the farm had been hit, but they still thought their father might have a plan of some sort and it was Finbarr who asked, ‘What’s to do?’

‘We must leave here, that’s all,’ Matt said.

‘Leave the farm?’ Sean asked.

‘Yes,’ Matt affirmed. ‘And Ireland too. We must leave Ireland and try our hands elsewhere.’

That shocked all the boys for not even Finbarr thought any plan would involve them all leaving their native land, though Mary, heartsore as she was, knew that was what they had to do.

Finbarr glanced at his brothers’ faces and knew he was speaking for all of them when he said, ‘We none of us would like that, Daddy. Is there no other way?’

‘Aye, the poorhouse if you’d prefer it,’ said Matt and he spoke with a snap because leaving was the thing he didn’t want to do either. ‘They have one in the town.’

At Finbarr’s look of distaste, he cried out, ‘Do you think this is easy for me? This is where I was born and where I thought I would die. It’s my homeland but we can’t live on fresh air.’ Then he added with an ironic smile, ‘Though we have made a good stab at it this year.’

Finbarr knew that well enough and didn’t bother commenting, but instead asked, ‘But where would we go?’

‘Where Norah Docherty has been urging me to go this past year,’ Mary said. ‘And that’s Birmingham, England. She’s in a place called Edgbaston and she says it’s not far from the city centre and she can put us up until we get straight with our own place and she says she can probably even help you all with jobs.’

Finbarr nodded for they all knew the Dochertys had left Ireland’s shore four years before when they were in danger of having to throw themselves on the mercy of the poorhouse to save the children from starving to death. Then an uncle living in Birmingham had offered them all a home with him in exchange for looking after him because he was afraid of being put in the poorhouse too. It was a lifeline for the Docherty family and they had all grasped it with two hands and were packed up and gone lock stock and barrel in no time at all.

Mary knew Norah found the life hard at first for Norah had written and told her that the house was terribly cramped. Her uncle couldn’t make the stairs and his bed had to be downstairs. But a man who lived just two doors down called Tim Bishop was the gaffer at a foundry in a place called Aston and he had put a word in for Norah’s husband Mick. He had jumped at the job they offered him and Mary said he’d been tired coming home especially at first, for the work was heavy, but then a job was a job and with Birmingham in the middle of a massive slump, to get one at all was great. She said you really needed someone to speak on your behalf to have a chance at all and Norah’s uncle had once worked at the same place as Tim Bishop and been well thought of and Tim Bishop approved of the family coming over to see to him in his declining years, for they all knew well the old man’s fear of ending up in the poorhouse or the workhouse, as it was commonly known.

‘This Tim Bishop Norah speaks of seems to be a grand fellow altogether,’ Mary said. ‘He had Mick set up in a job before he had been there five minutes. Please God that he may do the same for us.’

‘Yeah, but what sort of job?’ Colm grumbled. ‘Don’t know that I would be any good in Birmingham or anywhere else either,’ he said. ‘The only job I know how to do is farming.’

‘Well you can learn to do something else can’t you?’ Matt barked. ‘Same as I’ll have to do.’

‘We’ll all have to learn to do things we’re not used to,’ Mary said. ‘Life is going to be very different to the life we have here but that’s how it is and we must all accept it.’

Mary had a way of speaking that brooked no argument, as the boys knew to their cost, and anyway Finbarr knew she made sense and he sighed and said, ‘So what happens now?’

‘Well travel costs money,’ Mary said. ‘And that’s something we haven’t got a lot of, so we sell everything we don’t need. Your father has sold all the cattle and even got something for the carcasses of the cow and young calf but it isn’t enough. We’ll sell everything on the farm because we can hardly take anything but essentials with us anyway.’

Sad days followed as the children watched the only home they had ever known disappearing before their eyes. The neighbours rallied, one took the cart and horse and another took the hens the fox hadn’t killed and rounded up the sheep and yet another said he would have the plough and even the tools were sold. It was hard to get rid of the dogs and though Angela could only remember flashes of that time she remembered crying when Matt said the dogs had to go. All were upset. ‘They are going to good homes,’ Matt promised her and she remembered his husky voice and the way his eyes looked all glittery.

Barry hadn’t liked to see the dogs go either but knew he had to be brave for Angela and so he said, ‘We can’t take dogs to this place Mammy said we’re going to, Angela, so they have got to stop here.’

‘They’d hardly like it in Birmingham anyway,’ Mary said. ‘Their place is here.’

‘I thought mine was,’ Gerry said.

‘Gerry, you’re too old to moan about something that can’t be changed,’ Mary said sharply. ‘What can’t be cured must be endured – you know that.’

‘Who’s having the table?’ Barry asked.

‘The person who has bought the cottage,’ Mary said. ‘That’s Peter Murphy and he asked me to leave the table and chairs, my pots and all, the easy chairs, stools and settle, the butter churn and the press and all the beds. I was happy to do it and he gave me a good, fair price for them too.’

‘Funny to think of someone living here when we’ve gone,’ Gerry said.

‘I suppose,’ Mary said. ‘But I’d rather someone was getting the good out of it than it just falling to wrack and ruin.’

They all agreed with that but when they assembled the following Saturday very very early that late April morning Mary looked at their belongings packed in two battered cases and two large bass bags and her heart felt as heavy as lead. She wasn’t the only one. As they left the farmhouse for the last time they all felt strange not to see the clucking hens dipping their heads to eat the grit between the cobbles outside the cottage door, nor to hear the barking of the dogs. As they made their way to the head of the lane where the neighbour who bought the horse and cart would be waiting for them to take them down to the rail bus station in the town, they missed seeing the horse and cows sharing the field to one side and to the other side of the lane the tilled and furrowed fields, now bare with nothing planted in them. They missed seeing the sheep on the hillside pulling relentlessly on the grass.

Sad though they were to leave, the children were also slightly excited, but Mary’s excitement was threaded through with trepidation for she had never gone far from home before, none of them had, and she looked at the youngsters’ eager though slightly nervous faces and hoped to God they were doing the right thing.

All knew where the McCluskys were bound and even at that early hour some neighbours had come to see them off and wish them God speed and their good wishes almost reduced Mary to tears as she hugged the women and shook hands with the men and led the way on to the rail bus where she and Matt got them all settled in.

They were soon off, the little rail bus was eating up the miles, but it was only the start of the long journey to Birmingham. They would leave the rail bus at a place called Strabane and from there get a train to the docks at Belfast. Then a boat would take them across the sea to Liverpool where another train would take them from there to Birmingham. The rail journey to Strabane had begun to pall but they all perked up a bit when it was time to board the boat.

Mary was very nervous of going up the gangplank and once on deck the way the boat seemed to list from one side to another was very unnerving, but what worried her most was the safety of the children. Not the older boys, they should be all right, but it was Barry and little Angela she was concerned about. What if one of them was to fall overboard? Oh God, that didn’t bear thinking about!

She didn’t express her fears, she knew the boys would only laugh at her, but she said to Finbarr and Colm, ‘You make sure you look after Barry and Angela. Make sure you keep them safe,’ knowing they would more than likely want to explore the ship. Her gallivanting days were over and she was finding it hard enough to keep her balance now and they hadn’t even set off yet.

‘I don’t need anyone to look after me,’ Barry declared. ‘I can look after myself.’

‘You’ll do as you are told,’ Mary said sharply to Barry. ‘And you mind what Finbarr and Colm say.’

Barry made a face behind his mother’s back and Finbarr clipped his ear for his disrespect. ‘Ow,’ he said holding his ear and glaring at Finbarr.

‘Never mind “ow”,’ Finbarr said. ‘You behave or we’ll not take you anywhere. We’ll just take Angela because she always does as she is told.’

‘Yes,’ Colm said, ‘you’d like to see around the ship wouldn’t you, Angela?’

Angela wasn’t sure, it looked a big and scary place to her, but she knew by the way the question was asked what Colm wanted her to say so she nodded her head slowly and said, ‘I think so.’

Barry said nothing more because he definitely did want to see over the ship and Finbarr could be quite stern sometimes and he knew his Mammy would never let him go on his own. Anyway he hadn’t time to worry about it because the call came for those not travelling on the boat to disembark and exhilaration filled him for he knew they would soon be on their way. Finbarr put Angela up on his shoulder because she couldn’t see over the rail and from there she watched those wishing to disembark scurry down the gangplank to stand on the quayside and wave as the sailors raised the gangplank and hauled in the thick ropes that had attached the ship to round things on the quayside that Finbarr told her were bollards. Then the ship’s hooter gave such a screech Angela nearly jumped off Finbarr’s shoulder. The ship’s engines began to throb and Finbarr lifted her down and Angela felt the whole deck vibrate through her feet as the ship moved slowly out to sea.

Matt and Mary joined the children at the rail as they watched the shores of Ireland slip away and Mary suddenly felt quite emotional, for she had never had any inclination to leave her native land. The sigh she gave was almost imperceptible, but Matt heard it and he put his gnarled, work-worn hand over Mary’s on the deck rail. ‘We’ll make it work,’ he said to her. ‘We’ve made a right decision, the only decision, and we will have a good living there, you just see if we don’t.’

Mary was unable to speak, but she turned her hand over and squeezed Matt’s. It was hard for him too for farming was all he knew, but he was a hard worker and had always been a good provider, and she had a good pair of hands on her too. She swallowed the lump in her throat and said, ‘I know we will, Matt, I’m not worried about that.’

And while the children went off to explore they stood together side by side and watched the shore of Ireland fade into the distance.

Mary was to find that she wasn’t a very good sailor though the children seemed unaffected and wolfed down the bread and butter Mary had brought. It had been a long time since that very early breakfast, but Mary could eat nothing and Matt ate only sparingly. Mary thought that he had probably done that so that the children could eat their fill rather than any queasiness on his part.

Mary was very glad to leave the boat and be on dry land again, but she was bone weary and it would be another couple of hours before they would reach Birmingham. All the children were tired and before the train journey was half-way through Angela climbed on to Mary’s lap and fell fast asleep. She slept deeply as the train sped through the dusky evening and did not even stir when it pulled up at New Street Station. Oh how glad Mary was to see a familiar face as she stepped awkwardly from the train, for Mick Docherty was waiting with a smile of welcome on his lips. He was unable to shake Mary’s hand for she had Angela in her arms. But he shook hands with Matt and the children one by one, even Barry, much to his delight.

He led the way to the exit and Mary was glad of that for she had never seen so many people gathered together. The noise was incredible, so many people talking, laughing, the tramp of many feet, thundering trains hurtling into the station to stop with a squeal of brakes and a hiss of steam, steam that rose in the air and swirled all around them smelling of soot. There was a voice over her head trying to announce something and someone shouting, she presumed selling the papers he had on the stall beside him, but she couldn’t understand him. Porters with trolleys piled high with luggage weaved between the crowds urging people to, ‘Mind your backs please.’

‘We’ll take a tram,’ Mick said as he led the way to the exit. ‘We could walk, and though it’s only a step away, I should say you’re weary from travelling. Yon young one is anyway,’ he went on, indicating Angela slumbering in Mary’s arms.

‘Aye. And little wonder at it,’ Matt said. ‘We’ve been on the go since early morning and I’m fair jiggered myself.’

‘Aye, I remember I was the same,’ Mick said. ‘Well you can seek your bed as soon as you like, we keep no late hours here, but Norah has a big pan of stew on the fire and another of potatoes in case you are hungry after your journey.’

The boys were very pleased to hear that. They had hoped that somewhere there might be food in the equation, but now they were out of the station on the street and no one said anything, only stood and stared for they had never seen so much traffic in the whole of their lives. Mary was staggered. She’d thought a Fair Day in Donegal Town had been busy, but it was nothing like this with all these vehicles packed onto the road together. Hackney cabs ringed the station and beyond them there were horse-drawn vans and carts mixed with a few of the petrol-driven vehicles she had heard about but never seen and bicycles weaved in and out among the traffic. A sour acrid smell hit the back of her throat and there was a constant drone, the rumble of the carts, the clip clopping of the horses’ hooves sparking on the cobbles of the streets mixed with the shouts and chatter of the very many people thronging the pavements.

And then they all saw the tram and stopped dead. They could never have imagined anything like it, a clattering, swaying monster with steam puffing from its funnel in front and they saw it ran on shiny rails set into the road. Getting closer it sounded its hooter to warn people to get off the rails and out of the way and Mary found herself both fascinated and repelled by it. ‘That’s good,’ Mick said as he led them to a tram stop just a little way from the hackney cabs, ‘we’ve had no wait at all.’

‘Yes,’ Mary said, ‘but is it safe?’

Mick laughed. ‘It’s safe enough,’ he said. ‘Though I had my doubts when I came over first.’

Mary mounted gingerly, helped by the boys because she still had the child in her arms. She was glad to sit for even a short journey though she slid from side to side on the wooden seat for Angela was a dead weight in her arms. It seemed no time at all before Mick was saying, ‘This is ours, Bristol Street.’ And once they had all alighted from the tram he pointed up the road as he went on, ‘We go up this alleyway called Bristol Passage and nearly opposite us is Grant Street.’

Mary saw a street of houses such as she never knew existed, not as homes for people – small, mean houses packed tight against their neighbours and Mary felt her spirit fall to her boots for she never envisaged herself living in anything so squalid. The cottage she had left was whitewashed every winter, the thatch replaced as and when necessary and the cottage door and the one for the byre and the windowsills painted every other year, and she scrubbed her white stone step daily.

She could not say anything of course nor even show any sign of distaste. One of these was the house of her friend, besides which she didn’t know how things worked here. Maybe in this teeming city of so many people houses were in short supply.

She hadn’t time to ponder much about this as Norah had obviously been watching out and had come dinning down the road to throw her arms around Mary, careful not to disturb Angela, but her smile included them all as she ushered them back to the house. ‘I have food for you all,’ she said, but added to Mary, ‘What will you do with the wee one?’

‘I think she is dead to the world,’ Mary said. ‘I see little point in waking her. She’d probably be a bit like a weasel if I tried. She hates being woken up from a deep sleep.’

‘Oh don’t we all?’

‘Yes,’ Mary agreed. ‘I suppose I’d hate it just as much. So if you show me where she is to sleep, I’ll take her straight up.’

‘That will be the attic,’ Norah said. ‘And you, Mick, get those boys sat around the table with a bowl of stew before they pass out on us.’ The boys sighed with relief and busied themselves sorting chairs around the table as Norah opened up the door against the wall and led the way up the two flights of stairs to the attic. There was a bed to one side, a chest and set of drawers, and a mattress laid on the floor. ‘That will do you two and Angela,’ Norah said. ‘The boys I’m afraid will have to sleep elsewhere for now.’

Mary was completely nonplussed at this though she knew Norah had made a valid point for she had four children of her own and the walls were not made of elastic. ‘Where will they sleep then?’

‘In Tim Bishop’s place,’ Norah said. ‘You know I told you he got the job for Mick?’

‘Oh yes,’ Mary said as she laid Angela down on the mattress and began removing her shoes. ‘Where does he live?’

‘Just two doors down,’ Norah said.

‘I suppose it’s him we shall have to talk to anyway about a job for Matt.’

‘Of course, I never told you Tim died last year.’

That took the wind right out of Mary’s sails because she had sort of relied on this Tim Norah had spoken so highly of to do something for them too and it might be more difficult for them than it had been for Mick Docherty. But a more pressing problem was where her sons were going to lay their heads that night. ‘So whose house is it now?’

‘His son Stan has it,’ Mary said. ‘Tim died a year ago and before he died he gave permission for Stan to marry a lovely girl called Catherine Gaskell. They had been courting, but they were only young, but unless they were married or almost married when his father died, Stan as a single man wouldn’t have had a claim on the house. Anyway they married and sheer willpower I think kept Tim alive to see that wedding for he died just three days later and now Stan and Kate have an unused attic and the boys can sleep there.’

‘I couldn’t ask that of perfect strangers.’

‘They’re not perfect strangers, not to me,’ Norah said. ‘They’re neighbours and I didn’t ask them, they offered when I said you were coming over and I couldn’t imagine where the boys were going to sleep. Stan said he’s even got a double mattress from somewhere. Anyway I can’t see any great alternative. Can you?’

Mary shook her head. ‘No and I am grateful for all you have done for us, but I’d rather not have Barry there. He is only seven and for now can share the mattress with us and let’s hope Matt gets a job and we get our own place sooner rather than later.’

‘I’ll say,’ Norah said. ‘And you can ask Stan about the job situation because he’s the Gaffer now. Apparently Mr Baxter who is the overall Boss said there was no need to advertise for someone else when Stan had been helping his dad out for years. So if anyone can help you out it’s him.’

That cheered Mary up a bit. And she did find Stan a very nice and helpful young man when she saw him later that evening. He had sandy hair and eyes and an honest open face, a full generous mouth and a very pleasant nature all told, but Mary did wonder because he was so young whether he would have as much influence as his father had had.

Still she supposed if he agreed to put in a word for Matt and the boys, for only Barry and Gerry were school age, the others could work and if he could help them all it would be wonderful, but only time would tell.

TWO (#ulink_1bb290a4-be78-510d-a769-837e9b271cfd)

Every morning for the whole of her short life Angela had woken early to the cock crow. She would pad across to the window and listen to the dogs barking as they welcomed the day and the lowing of the cows as they were driven back to the fields from the milking shed. When she dressed and went into the kitchen the kettle would be singing on the fire beside the porridge bubbling away in the pot and the kitchen would be filled with noise, for her father and brothers would be in from the milking after they had sluiced their hands under the pump in the yard and thick creamy porridge would be poured into the bowls with more milk and sugar to add to the porridge if wanted. It was warm and familiar.

The first morning in Birmingham she woke and was surprised to see Danny beside her for she couldn’t remember that ever happening before and she slipped out of bed, but the window was too high for her to see out of. She wondered if anyone else was awake because she was very hungry. She wandered back to bed and was delighted to see Barry’s deep-brown eyes open and looking at her. ‘Hello.’

‘Ssh,’ Barry cautioned. ‘Everyone but us is asleep.’

Angela thought Barry meant just their Mammy and Daddy and then she saw the children lying on the other mattress. She couldn’t remember the Dochertys from when they lived in Donegal but she remembered Mammy telling her they had four children now. And so she lowered her voice and said, ‘I’m ever so hungry, Barry.’

Barry didn’t doubt it because Angela had had none of the delicious supper him and the others had eaten the previous evening and he was hungry enough again, so he reckoned Angela must be starving. ‘Get your clothes on,’ he whispered. ‘Not your shoes. Carry them in your hand and we’ll go downstairs.’

‘What if no one’s up?’

‘They will be soon,’ Barry said confidently. ‘It’s Sunday and everyone will be going to Mass.’

‘Is it? It doesn’t feel like a Sunday.’

‘That’s because everything’s different here,’ Barry said. ‘Hurry up and get ready.’

They crept down the stairs quietly holding their shoes, but there was no kettle boiling on the range, nor any sign of activity, and no wonder for the time on the clock said just six o’clock. On the farm the milking would have all been done by that time, but in a city it seemed six o’clock on a Sunday is the time for laying in bed. And then he remembered there might be no breakfast at all because they were likely taking communion and no one could eat or drink before that. It wouldn’t affect Angela, nor he imagined the two youngest Dochertys, Sammy and Siobhan, whom he’d met the night before. They were only five and six, but the other two, Frankie and Philomena, were older. He had no need to fast either for he hadn’t made his First Holy Communion yet. Had he stayed in Ireland he would have made it in June, but here he wasn’t sure if it would be the same. It did mean though he could eat that morning and he searched the kitchen, which wasn’t hard to do since it was so tiny and, finding bread in the bin, he cut two chunks from one of the loaves, spread it with the butter he’d found on the slab and handed one to Angela.

But Angela just looked at him with her big blue eyes widened. ‘Here, take it,’ he said.

‘It must be wrong,’ she cried. ‘We’ll get into trouble.’

‘I might get into trouble but you won’t,’ Barry assured Angela. ‘But you must eat something because you have had nothing since the bread and butter in the boat dinner time yesterday. We had stew last night but you were too sleepy and Mammy put you to bed, so you must eat something and that’s what I’ll say if anyone is cross. You won’t be blamed so take it.’

He held the bread out again and this time Angela took it and when she crammed it in her mouth instead of eating it normally Barry realized just how hungry she had been and he poured her a glass of milk from the jug he had found with the butter on the slab to go with it. ‘Now you’ve got a milk moustache,’ he said with a smile.

Angela scrubbed at her mouth with her sleeve and then said to Barry, ‘Now what shall we do?’

‘Well, it doesn’t seem as if anyone is getting up,’ Barry said, for it was as quiet as the grave upstairs when he had a listen at the door. ‘So how about going and having a look round the place we are going to be living in?’

‘Oh yes, I’d like that.’

‘Get your shoes on then and we’ll go,’ Barry said.

A little later when Barry opened the front door Angela stood on the step and stared. For all she could see were houses. Houses all down the hill as far as she could see. She stepped into the street and saw her side of the street was the same. And she couldn’t see any grass anywhere. There had been other houses in Ireland dotted here and there on the hillside, but the only thing attached to their cottage was the byre and the barn beyond that. There wasn’t another house in sight and you would have to go to the head of the lane to see any other houses at all. To see so many all stacked up tight together was very strange.

‘Where do you go to the toilet here?’ Angela asked, suddenly feeling the urge to go.

‘Down the yard,’ Barry said. ‘I’ll show you. Mr Docherty took me down the yard last night, we need a key.’

He nipped back into the house to get it before taking Angela’s hand and together they went down to the entry of the yard. As Barry had seen in the dark, now she also saw that six houses opened on the grey cobbled yard and crisscrossing washing lines were pushed high into the sooty air by tall props.

Barry said, ‘Norah told us last night some women wash for other people. Posh people, you know, because it’s a way of making money and they have washing out every day of the week except Sunday. And this is the Brewhouse where Mick says all the washing gets done,’ he added as they went past a brick building with a corrugated tin roof.

The weather-beaten wooden door was ajar and leaning drunkenly because it was missing its top hinges. Angela peeped inside and wrinkled her nose. ‘It smells of soap.’

‘Well it would be odd if it smelled of anything else,’ Barry said, ‘and these two bins we’re passing have to be shared by the Dochertys and two other families. One is for ashes, called a miskin, and the black one is for other rubbish.’

‘Don’t you think it’s an odd way of going on?’ Angela asked.

Barry nodded. ‘I do,’ he said in agreement. ‘And you haven’t seen the toilets yet, they’re right at the bottom of the yard and two other families have to share them as well. They have a key to go in and you must lock it up afterwards. The key is always kept on a hook by the door.’

Angela found it was just as Barry said and as she sat on the bare wooden seat and used the toilet she reflected that Mammy had been right, they had an awful lot of things to get used to.

Stopping only to put the key back on its hook, the two started to walk down the slope towards Bristol Street and Barry wondered what Angela was thinking. He’d had a glimpse of the area as he had walked up Grant Street with everyone else the previous evening. He didn’t think they looked very nice houses, all built of blue-grey brick, three storeys high with slate roofs and they stood on grey streets and behind them were grey yards. He didn’t think his mother had been impressed either, but she had covered the look of dismay Barry had glimpsed before anyone else had seen it.

So he wasn’t surprised at Angela’s amazement as she looked from one side to the other. ‘There’s lots of houses aren’t there Barry?’ she said as they started to go down Bristol Passage.

‘Yeah, but this is a city and lots of people live in a city and they all have to have houses.’

‘Yes, I suppose,’ Angela said.

‘D’you think you’ll like living here?’ he said as they strode along Bristol Street. Despite it being still quite early on a Sunday morning there were already some horse-drawn carts and petrol lorries on the road and a clattering tram passed them, weaving along its shiny rails. There were plenty of shops too, all shut up and padlocked. Angela said, ‘I don’t know.’

‘It’s all strange here isn’t it? Not a bit like home.’

‘No, no it isn’t.’

‘Tell you what though,’ Barry said. ‘This is probably going to be our home now, not Mr and Mrs Docherty’s house, but this area. So I’m going to make sure I like it. Don’t do no good being miserable if you’ve got to live here anyway.’

That made sense to Angela but Barry always seemed to be able to explain things to her so she understood them better. ‘And me,’ she said.

‘Good girl,’ Barry said with a beam of approval and he reached for her hand as he said, ‘We best go back now because we’ll probably be going to an early Mass and we daren’t be too late.’

Everyone was up at the Dochertys’ and Mary asked where they had both been and would have gone for Barry when he attempted to explain, but Norah forestalled her. ‘It was obvious Angela would wake early,’ she said to Mary, ‘because she had her sleep out and it was good of Barry to take her downstairs and let us have a bit of a lie in.’

‘But to take food without asking!’

‘Well he couldn’t ask me without waking me up first and that wouldn’t have pleased me at all,’ Norah pointed out and added with a little laugh, ‘It was just a bit of bread and it’s understandable that Angela would be hungry. Don’t be giving out to them their first morning here.’

‘I was starving,’ Angela said with feeling.

‘Course you were,’ Norah said. ‘You hadn’t eaten for hours.’

Barry let out a little sigh of relief, very grateful to Mrs Docherty for saving him from the roasting he was pretty sure he had been going to get from his mother, and when she said, ‘Anyway come up to the table now for I have porridge made for you two and Sammy and Siobhan,’ the day looked even better.

St Catherine’s Catholic Church was just along Bristol Street, no distance at all, and Norah pointed out Bow Street off Bristol Street where the entrance to the school was. ‘I will be away to see about it tomorrow,’ Mary said. ‘I hope they have room for Barry and Gerry for I don’t like them missing time. Wish I could get Angela in too because she’s more than ready for school.’

‘I thought that with Siobhan and was glad to get her in in September,’ Norah said. ‘I think when they have older ones they bring the young ones on a bit.’

‘You could be right,’ Norah said. ‘I know our Angela is like a little old woman sometimes, the things she comes out with.’

‘Oh I know exactly what you mean,’ Mary said with feeling. ‘Mind I wouldn’t be without them and I did miss the boys last night. Be glad to see them at Mass this morning.’

The boys were waiting for them in the porch and they gave their anxious mother a good account of Stan Bishop and his wife Kate, who they said couldn’t have been kinder to them. That eased Mary’s mind for her children had never slept apart from her in a different house altogether and she thought it a funny way to go on, but the only solution in the circumstances.

After Mass, Norah introduced them to the priest, Father Brannigan, and he was as Irish as they were. Mary’s stomach was growling embarrassingly with hunger and she hoped he couldn’t hear it. She also hoped meeting him wouldn’t take long so she could go home and eat something, but she knew it was important to be friendly with the priest, especially if you wanted a school place for your children. Matt understood that as well as she did and they answered all the questions the priest asked as patiently as possible.

It might have done some good though, because when he heard the two families were living in a cramped back-to-back house with the older boys farmed out somewhere else, he said he’d keep his ear to the ground for them.

‘Well telling the priest your circumstances can’t do any harm anyway,’ Norah said. ‘Priests often get to know things before others.’

‘No harm at all,’ Mary agreed. ‘Glad he didn’t go on too long though or I might have started on the chair leg. Just at the moment my stomach thinks my throat’s been cut.’

It was amazing how life slipped into a pattern, so that living with the Dochertys and eating in shifts became the norm. Gerry and Barry were accepted into St Catherine’s School and went there every day with all the Docherty children and Angela was on the waiting list for the following year when she would be five. Better still, Stan Bishop said he could get Sean into the apprentice scheme to be a toolmaker and Gerry could join him in two years’ time, and he could find a labouring job for Matt the same as Mick, so that by the beginning of June the two men and the boy Sean were soon setting off to work together.

Sadly, Stan could find nothing for the two older boys who were too old for the apprentice scheme, which had to be started at fourteen, and there was no job for them in the foundry. They were disappointed but not worried. It wasn’t like living in rural Donegal. Industrial Birmingham was dubbed the city of one thousand trades and just one job in any trade under the sun would suit Finbarr and Colm down to the ground.

So they did the round of the factories as Stan advised, beginning in Deritend because it was nearest to the city centre and moving out to Aston where the foundry was. They started with such high hopes that surely they would be taken on somewhere soon. ‘The trick,’ Stan said, ‘is to have plenty of strings to your bow. Don’t go to the same factory every day because they’ll just get fed up with you but don’t leave it so long that they’ve forgotten who you are if they have given you any work before. And if you’re doing no good at the factories go down to the railway station and offer to carry luggage. It’s nearly summer and posh folk go away and might be glad of a hand and porters are few and far between. Or,’ he added, ‘go to the canal and ask if they want any help operating the locks or legging the boats through the tunnels.’

‘What’s that mean, “legging through the tunnel”?’

‘You’ll find out soon enough if they ask you to do it,’ Stan said with a smile. ‘Just keep going and something will turn up I’m sure.’

They kept going, there was nothing else to do, but sometimes they brought so little home. Everything they made they gave to their mother but sometimes it was very little and sometimes nothing at all. They felt bad about it, but Mary never said a word, as she knew they were trying their best, and while they were living with the Dochertys money went further, for they shared the rent and the money for food and coal. But she knew it might be a different story if ever they were to move into their own place.

However, that seemed as far away as jobs for her sons, but life went on regardless. Barry did make his First Holy Communion with the others in his class, and not long after it was the school holidays and they had a brilliant summer playing in the streets with the other children. Mary wasn’t really happy with it, but there was nowhere else for them to play. Anyway all the other mothers seemed not to mind their children playing in the streets, but she was anxious something might happen to Angela. ‘You see to her, Barry,’ she said.

‘I will,’ Barry said. ‘But she can’t stay on her own in the house. It isn’t fair. Let her play with the others and I’ll see nothing happens to her.’

‘Don’t know what you’re so worried about,’ Norah said. ‘That lad of yours will hardly let the wind blow on Angela.’

‘I know,’ Mary said. ‘He’s been like that since Angela first came into the house, as if he thought it was his responsibility to look after her. He’s a good lad is Barry and Angela adores him.’

‘He’s going to make a good father when the time comes I’d say,’ Norah said.

‘Aye. Please God,’ Mary said.

Angela thought it was great to be surrounded by friends as soon as she stepped into the street. She had been a bit isolated at the farm. Funny that she never realized that before, but having plenty of friends was another thing she decided she liked about living in Birmingham.

Christmas celebrated by two families in the confines of one cramped back-to-back house meant there was no room at all, but plenty of fun and laughter. There was food enough, for the women had pooled resources and bought what they could, but there was little in the way of presents for there was no spare money. Many of the boots, already cobbled as they were, had to be soled and heeled and Mary took up knitting again and taught Norah. The wool they got from buying old cheap woollen garments at the Rag Market to unravel and knit up again so that the families could have warmer clothes for winter.

January proved bitterly cold. Day after day snow fell from a leaden grey sky and froze overnight, so in the morning there was frost formed on the inside of windows in those draughty houses. Icicles hung from the sills, ice scrunched underfoot and ungloved fingers throbbed with cold.

Life was harder still for Finbarr and Colm toiling around the city in those harsh conditions to try and find a job of any sort to earn a few pennies to take home. So many factory doors were closed in their faces and when the cold eventually drove them home they would huddle over the fire to still their shivering bones and feel like abject failures. No one could help and neither of them knew what they were going to do to help ease the situation for the family.

Slowly the days began to get slightly warmer as Easter approached. Angela would be going to school in the new term and she was so excited. She was just turned five when she walked alongside Mary for her first full day at school on April 15th. She was so full of beans it was like they were jumping around inside her. At the school she was surrounded by other boys and girls all starting together and they regarded each other shyly. When their mothers had gone their teacher, Miss Conway, took them into the classroom, which she said would be their classroom, and told them where to sit.

Angela was almost speechless with delight when she realized she had a desk and chair all to herself. After living with the Dochertys for months, she was used to sharing everything. She looked around and noticed what a lot of desks there were in the room, which was large with brown wooden walls and very high windows with small panes. There were some pictures, one with numbers on it, one with letters, and a map above the blackboard that stood in front of the high teacher’s desk.

Another little girl was assigned the desk next to Angela and she turned to look at her, envying the pinafore she wore covering her dress. In fact most of the girls wore pinafores but her Mammy said funds didn’t run to pinafores and she knew better than to make a fuss over something like that. The girl had straight black hair that fell to her shoulders and dark brown eyes, but her lips looked a bit wobbly as if she might be about to cry and her face looked as if she was worried about something, so Angela smiled at her and the little girl gasped. What the little girl thought was that she’d never seen anyone so beautiful with the golden curls and the deep blue eyes and pretty little mouth and nose. Spring sunshine shafted through the tiny windows at that moment and it was like a halo around Angela’s head. ‘Oh,’ said the little girl with awe. ‘You look like an angel.’

Angela laughed, bringing the teacher’s eyes upon her. She thought maybe laughing wasn’t allowed at school and she was to find that it wasn’t much approved of. Nor was talking, for when she tried whispering to the other girl, ‘I’m not an angel, I just look like my mother,’ the teacher rapped the top of her desk with a ruler, making most children in the room jump. ‘No talking,’ she rapped out and Angela hissed out of the corner of her mouth, ‘Tell you after.’

And later, in the playground, she told the whole story of how she ended up living with the McCluskys, according to what Mary had told her. ‘Funny you thought I looked like an angel,’ she said. ‘Because my real mammy thought so too and she insisted I was called Angela. All the others looked like my father.’

‘And they all died,’ the girl said. ‘And your mammy and daddy as well?’

Angela gave a brief nod and the other girl said, ‘I think that’s really sad.’

Angela shook her head. ‘It isn’t really, because I can’t remember them at all. Mammy, I mean Mary, has a photograph of them on their wedding day. It was stood on the dresser at home and I suppose it will come out again when we have our own house, but I have stared at it for ages and just don’t remember them. And Mary and Matt McClusky have loved me as much as if I had been one of their own children and the boys are like brothers to me.’

‘Huh,’ said the other girl, ‘I have no time for brothers. I have two, both younger than me, and a proper nuisance they are.’

Angela laughed and said, ‘What’s your name?’

‘Maggie. Maggie Maguire and my brothers are called Eddie and Patrick. But I think Mammy is having another one and that will probably be a boy as well. I’d love a sister.’

‘So would I,’ Angela admitted. ‘Shall we just be good friends instead?’

‘Yes, let’s.’ And so a bond was formed between Angela Kennedy and Maggie Maguire from that first day.

THREE (#ulink_95e51e90-69ca-542b-a577-c9159e7c4c23)

Just after Angela began school, the priest heard of a house that would shortly be vacant due to the death of the tenant and Mary went straight down to see the landlord. She took her marriage lines with her and the birth certificates of the children and to prove her honesty she carried a recommendation from the priest and she secured the house, which was in Bell Barn Road and only yards from Maggie’s house in Grant Street.

Mary was delighted to get a place of her own though she did wonder how she would furnish it, but when she said this to Matt he had a surprise for her. ‘With the sale of the farm and land I had money over when I bought the tickets to get here,’ he told her. ‘Not knowing when I would get a job when we arrived, I put it in the Post Office and it’s still there, so we’ll go off to the Bull Ring Saturday afternoon and see what we can pick up to make the place more homely at a reasonable price.’

Mary was really pleased that Matt had kept the money safe and that he had kept knowledge of it to himself as well, or she might have been tempted to dip into it from time to time, and where would they be now if she had done that? They’d have a house but not a stick of furniture to go into it.

In fact it wouldn’t have been that bad because the previous tenant had died and his family didn’t want much of his furniture, so the house already had two armchairs, a small settee and a sideboard downstairs, and a bed and wardrobes were left in the bedroom upstairs. Norah went to inspect the house and agreed with Mary it needed a thoroughly good clean before anything else and they undertook that together. In the Bull Ring Mary and Matt bought oilcloth for the floor, a big iron-framed bed for the boys in the attic and two chests for their clothes. For Angela there was a truckle bed that was to be set up in the bedroom because Mary declared it wasn’t seemly for her to share the attic with so many boys when she was not even officially related to them.

The purchases severely depleted Matt’s savings and money from day to day was tighter than ever and Norah was finding it hard to make the money stretch. If some days they seemed to eat a lot of porridge it was because a pair of boots needed repair or there was a delivery of coal to pay for. Mary worried about the meals often. ‘Men need more than porridge,’ she said to Norah. ‘If Finbarr and Colm do get a job they’ll hardly be able for it and Matt works hard now and needs good food or he might take sick.’

Sometimes she would take Angela with her when she went to the Bull Ring on a Saturday afternoon and she would hide away and send Angela into the butcher’s and ask for a bone for the dog. The butcher knew there was little likelihood of there being any sort of dog; most people had trouble enough feeding themselves. But he would be charmed by the look of Angela, her winning smile and good manners, and she usually came out with a bone with lots of meat still on it. Often the butcher would slip her something else, like a few pieces of liver, or a small joint because he would have to throw them away anyway at the end of the day.

And Mary would boil up the bones and strip them of meat for a stew along with vegetables and dumplings to fill hungry men. She would do the same with pigs’ trotters if she had the pennies to buy them. She could make a couple of loaves of soda bread almost without thinking about it and if there was no money for butter, mashed swede would do as well. Cabbage soup was also on the menu a lot so though no one starved, the monotony of the diet got to everyone, but no one complained for there was little point.

Finbarr and Colm were filled with shame that they couldn’t do more to help and knowing this, Gerry felt almost embarrassed to join Sean on the apprenticeship scheme in 1902 when he turned fourteen and left school. ‘Don’t feel bad about it,’ Finbarr said. ‘You go for it. I would do the same given half a chance.’

Both apprentice boys were full of praise for Stan Bishop and thought he was a first-rate boss, always patient with them if they made mistakes in the early days. ‘He’s a decent man,’ Mary said. ‘I always thought it.’

‘He’s a happy bloke, I know that,’ Sean said. ‘He’s always humming a tune under his breath and he sings at home.’

‘He does that,’ Colm said. ‘He’s good, or it sounds all right to me anyway, and Kate has a lovely voice.’

‘Well she’s in the choir,’ Mary pointed out. ‘That’s why they always go to eleven o’clock Mass. She sometimes sings when she is in the house on her own because I have heard her a time or two when I have been up visiting Norah. She has got a lovely voice, but then she seems a lovely person. She always seems to have a smile on her face.’

She had. It was evident to everyone how happily married they were and there was speculation why there had been no sign of a child yet, though Mary had confided to Norah that she thought Kate looked rather frail. ‘I don’t think it would do her good to have a houseful of children,’ she said. ‘It would pull the body out of her.’

‘We none of us can do anything about that though,’ Norah said. ‘It’s God’s will. The priests will tell you that you must be grateful for whatever God sends, be it one or two or a round dozen.’

‘I know,’ Mary said and added, ‘They’re quick enough to give advice. But no one helps provide for those children, especially with jobs the way they are.’

‘I know,’ Norah said. ‘And then wages are not so great either. I mean, my man’s in work and I am hard pressed to make ends meet sometimes. At least Sean and Gerry are learning a trade, that’s lucky.’

‘Aye, if there is a job at the end of it.’

‘There’s the rub,’ Norah said, because many firms would take on apprentices on low pay and get rid of them when they were qualified and could command far better wages, and take on another lot to train as it was cheaper for them.

‘I’m not looking that far ahead,’ Mary said. ‘I’ll worry about it if it happens. As for Kate Bishop, she seems not to be able to conceive one so easy, so I doubt they’ll ever be that many eventually.’

‘Don’t be too sure,’ Norah said. ‘I’ve seen it before. They have trouble catching for one and then as if the body knows what to do, they pop another out every year or so.’

‘Proper Job’s comforter you are,’ Mary said and added with a smile, ‘Are you going to put the kettle on or what? A body could die of thirst in this place.’

There was no change in the McClusky household over the next couple of years. Sean, now halfway through his apprenticeship, got a rise, but it was nothing much, and Matt too was earning more so the purse strings eased, but only slightly. Towards the end of that year, Norah told Mary she was sure Kate Bishop was pregnant. There was a definite little bump that hadn’t been there before. By the turn of the year Stan was nearly shouting it from the rooftops and though he was like a dog with two tails, Kate was having a difficult pregnancy and was sick a lot and not just for the first three months, like the morning sickness many women suffered from.

Many women gave her advice of things they had tried themselves, or some old wives’ tale they had heard about, for all the women agreed with Mary that Kate Bishop couldn’t afford to lose weight for she had none to lose. She was due at Easter and she hardly looked pregnant as the time grew near. ‘God!’ Mary said to Norah. ‘I was like a stranded whale with all of mine. I do hope that girl is all right. I saw her the other day and couldn’t believe it, her wrists and arms are very skinny and her skin looks sort of thin.’

‘She’s still singing every Sunday morning though,’ Norah said. ‘And she practises through the day, does her scales and everything.’

‘I suppose it helps keep her mind off things.’

‘Maybe. Can’t be long now though.’

On the fifteenth of April Kate Bishop’s pains began in the early hours and though Stan had engaged a nurse, it was soon apparent that the services of a doctor were needed and he booked an ambulance, and while he was waiting for it to come Kate had a massive haemorrhage and died.

Stan was distraught at losing his beloved wife and he couldn’t cope with his new-born son. Both Mary and Norah were often in the house with Stan, mainly caring for the baby and making meals for Stan he had no appetite to eat. Sometimes he seemed almost unaware of their presence and both Mary and Norah felt quite helpless that they could do nothing to ease Stan’s pain and were glad when Kate’s older sister Betty arrived.

She was married to Roger Swanage and though they lived in a nice house that Roger had inherited from his widowed mother, still they had no children though Betty had been trying for years to conceive. She took charge of Stan’s son and Roger took it upon himself to organize the funeral for Kate because Stan seemed incapable, though he did insist on choosing the hymns because Kate had favourites and he chose those.

Betty seemed surprised at the numbers who turned out for the funeral but Kate had been popular and very young to lose her life in that tragic way, so the church was packed, including many men, as the foundry was closed that day as a mark of respect. Even those not going to the Mass stood at their doorways in silence as the cart carrying the coffin passed, some making the sign of the cross, and any men on the road removed their hats and stood with bowed heads.

The Requiem Mass seemed interminable and Mary heard many sniffs in the congregation as Father Brannigan spoke of the grievous loss of the young woman leaving a child to grow up without a mother’s love, and the loss would be felt through the whole community, but particularly by her grieving husband and her family, and the choir where she had been a stalwart member. Eventually it was over and the congregation moved off to Key Hill Cemetery in Hockley, as St Catherine’s didn’t have its own cemetery.

The wind had increased during the Mass and it buffeted them from side to side, billowing all around them, and when they stood by the open grave the wind-driven rain attacked them, stabbing at their faces like little needles – a truly dismal day. As the priest intoned further prayers for the dear departed and they began lowering the coffin with ropes, Stan gasped and staggered and would have fallen, but Matt reached out and put a hand upon his shoulder. ‘Steady man. Nearly over.’ The clods of earth fell with dull thuds on to the lid and they all turned thankfully away and walked back through the gusty, rain-sodden day to the back room of The Swan where a sumptuous feast was laid out, made by the landlord’s wife and her two daughters.

Everyone seemed to think that it was right and proper that Kate’s childless sister should rear the motherless child. Even Father Brannigan saw it as an ideal solution when he called to see them a week after the funeral to discuss the child’s future and baptism.

‘And you are fully prepared to take on the care of the child?’ he asked Betty, though his gaze took in Roger too.

It was Betty who answered, ‘Oh yes, Father,’ she said. ‘Kate was my own younger sister and I’m sure she would wish me to do this, and how can I not love her child as if he were my own?’

‘And have you children of your own?’

‘Sadly no,’ Betty said. ‘The Lord hasn’t seen fit to grant me any and we have a fine house waiting for a child to fill it.’

‘Well I think that eminently suitable,’ the priest said. ‘What of you, Stan? Are you in agreement with this?’

Stan turned vacant eyes on the priest. He wondered how he could explain to the priest, without shocking him to the core, that he cared little for the tiny mite held in Betty’s arms so tenderly, the mite his wife had died giving birth to. And he contented himself giving a shrug of his shoulders.

Father Brannigan saw the intense sorrow in his deep eyes and knew for Stan the pain of his loss was too raw to discuss things to do with the child, and so he thought it a good thing his sister-in-law was there. He turned again to Betty. ‘And have you chosen names?’

‘Yes,’ Betty said decidedly. ‘I want him called Daniel.’

Stan’s head shot up at that and the priest was pretty certain he hadn’t known of Betty’s plan. And he hadn’t, and though he and Kate had discussed names, Daniel hadn’t been mentioned, yet Betty said Kate would approve of Daniel. ‘It was the name of our late father,’ she said to Stan.

Stan hadn’t the energy to protest and felt anyway he had no right. Betty was going to raise the child, therefore she should have the right to name that child too. And Betty could be quite right – since it was the name of Kate’s father she might have called him Daniel in the end. ‘I don’t mind what the child is called,’ he said, ‘but I want Matt and Mary McClusky as godparents.’

Mary was delighted to be asked but she noted the jealous way Betty held on to the child. While she was willing for Mary to take him from her and hold his head over the font so that the priest could dribble water over it, she took him back afterwards and would let no one else, not even his own father, hold him and Mary felt the first stirrings of unease. Stan on the other hand was pleased initially to leave everything to Betty and for Daniel to be taken back to their fine house in Sutton Coldfield after the christening.

‘Where is Sutton Coldfield?’ Mary asked Matt a few weeks later

‘I’m not sure myself,’ Matt said. ‘I know it’s a fair distance and a posh place, so Stan was telling me. He said Betty and Roger live in a big house built of red brick with a blue slate roof. And although it’s not on the doorstep it’s easy enough to get to because a little steam train runs from New Street Station and then the station in Sutton is just yards from their house.’

‘He’s going to see him soon isn’t he?’

Matt nodded. ‘This Saturday afternoon,’ he said. ‘He’ll have been with them nearly three weeks then and he wants to see how he has settled down and everything.’

Later Stan talked to Matt about how it had gone. ‘Tell you, Matt, when I saw him, I had the urge to grab him and bring him home where he belongs. But how could I care for him and work? Betty, on the other hand, already has the nursery fitted out for him, which is far more salubrious than any attic bedroom I could provide. There’s also a garden back and front and I could see much better surroundings unfolding for Daniel if I left him there with his aunt and uncle, though I know he will probably call them mammy and daddy and will grow up thinking of them as his parents.’

‘Like Angela did?’

‘Ah but, the difference was she was told from the start who her real parents were and that they had both died, which was the truth, but Daniel has a father, though he will hardly be aware of that.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because Betty said it would confuse the boy if I kept popping up every now and then, and it wasn’t as if I could offer him anything. She told me that if I cared for the boy I should stay out of his life and let them bring him up. The point is I know I can offer the child nothing, but I still wanted to see him, take him out weekends, you know, get to know him a bit, but Betty said if I intended doing that I would have to make alternative arrangements. She would only look after Daniel as long as I stayed away.’

Mary sighed when Matt told her that night what had transpired when Stan had gone to see his son. She wasn’t totally surprised. She had thought Betty was the type of person who wouldn’t want to share her dead sister’s child. In a way in her mind she was probably trying to forget he had parents and make believe that he was her own child she had given birth to.

In Mary’s opinion secrets like this were not healthy and they had a way of wriggling to the fore eventually, spreading unhappiness and distrust. ‘That’s very harsh,’ she said. ‘I mean at the moment it’s hard on Stan, but the longer Betty and her husband leave telling Daniel of his father, the greater the shock for the child. Stan might not be able to care for him and work, but that doesn’t mean he can’t be part of his life. I think he’s a lovely man and I’m sure the child as he grows would benefit from knowing him.’

‘I couldn’t agree more,’ Matt said. ‘He said Betty was adamant. I think I might call her bluff in time. If she loves Daniel like he says she’d not want to give him up so easy, but Stan probably won’t want to risk it.’

‘Does he miss him?’

‘I asked him that myself,’ Matt said. ‘I suppose that what you never had you can’t miss but Stan said he always feels like something is missing and he copes because he knows Daniel will be happy and well loved, for Betty dotes on him and her husband does too, only slightly less anxiously. He said he would never have to worry that they would ever be unkind to him and he will want for nothing – no going barefoot with an empty belly for him. As long as the boy is happy that’s all that matters to Stan.’

‘That’s what most parents want,’ Mary said. ‘Their children’s happiness, and he is a decent man for putting the needs of his son before his own.’

Angela was unaware of what had happened to Stan’s baby. She knew about the death of his wife giving birth to the child, that couldn’t be hidden from the children, but the baby had just seemed to disappear. Even Maggie living only doors away from Stan Bishop knew no more. It was no good asking questions because things like that were not discussed in front of children so the girls concluded the baby must have died too. ‘Shame though, isn’t it, for Stan to lose his wife and baby.’

‘Mm,’ Maggie said. ‘Though I don’t think men are that good at looking after babies.’

‘No, maybe not,’ Angela agreed. ‘I just feel sorry for him being left with nothing. Doesn’t seem fair somehow.’

‘My mammy says none of life is fair and those that think it is are going to be disappointed over and over,’ Maggie said and Angela thought that a very grim way of looking at things.

FOUR (#ulink_edf01276-851b-54e5-8aaa-fd0e08b0ca20)

Stan seemed to get over the loss of his wife in the end as everyone must, but for ages a pall of sadness hung over him. Barry started on the apprenticeship scheme in 1907, the same year his brother Sean finished, and Stan’s sadness wasn’t helped by the news he had to impart to Mary. ‘He was heartbroken when he came to tell me that the boys would have no job at the end of their apprenticeships,’ Mary told Norah. ‘Sean is out of work now like his older brothers and I suppose Gerry will be the same in two years’ time. Stan said he could do nothing about it because it was the company’s policy. It was a bit of a blow but not a total shock because that sort of thing is happening everywhere.’

‘I know but it isn’t as if they can get a job somewhere else using the skills they have learnt because there are no jobs.’

‘Aye that’s the rub,’ Mary said. ‘And now there’ll be another mouth to feed on the pittance they will be able to earn. I mean you can only tighten a belt so far. And when Gerry is finished too in two years’ time God knows what we are going to do.’

‘I’m the same,’ Norah said, ‘and this has decided me.’

‘What?’

‘My eldest Frankie is just eighteen so half-way through his apprenticeship and my brother Aiden was after writing to me, offering to find him a job in the place he works. They’re taking a lot of young lads on.’

‘But Aiden is in the States?’

‘I know, New York.’

‘But … But surely to God you don’t want your son going so far away?’

‘Course I don’t,’ Nora said. ‘What I want is for him to get a job somewhere local and meet a nice Catholic girl to marry and give me grandchildren to take joy from. But it’s not going to happen, not here. I know when we bid farewell that will be it and I’ll never see my son again but I can’t deny him this chance of a future. I see your lads day after day worn down by the fact they can get no job. Unemployment is like a living death and how can I put Frankie through that when Aiden is holding out the hand of opportunity to him?’

She couldn’t, Mary recognized that, but she knew Norah’s heart would break when her eldest son went away from her. And though her own heart ached for her sons she couldn’t help feeling glad that they had no sponsor in America.

Unbeknownst to her, though, Finbarr and Colm were very interested in Frankie Docherty’s uncle’s proposal. ‘He seems very certain he will have a job for you,’ Finbarr said.

‘Yes he is.’

‘What line of work is it?’

‘Making motor cars.’

Finbarr stared at him. There were a few petrol-driven lorries and vans and commercial vehicles but personal motor cars were only for the very wealthy, they had taken the place of carriages, and Finbarr didn’t think even in a country the size of America they would need that many. Frankie’s career might be short lived when he got to the States.

Frankie caught sight of Finbarr’s sceptical face and he said, ‘My Uncle Aiden says that America is not like here and that everyone who is someone wants a motor car. They can’t keep up with the demand. And they want to train mechanics too so that they can fix the cars when they go wrong.’

‘Right,’ Finbarr said. ‘You excited?’

Frankie nodded eagerly. ‘You bet I am,’ he said, and added, ‘I have to hide it from Mammy though.’

‘I can imagine,’ Finbarr said with a smile. ‘Well I wish you all the very best and I only wish Colm and I were going along with you.’

‘Wouldn’t you mind going so far away?’

‘Won’t you?’

‘Of course,’ Frankie said. ‘I expect to miss my family but that’s the choice you have to make, isn’t it. And you’ve got to deal with homesickness otherwise you will waste the chance you’ve been given.’

‘That’s pretty sound reasoning, Frankie,’ Colm said. ‘I imagine I would feel much the same.’

‘And me,’ said Finbarr.

‘Maybe I can get my uncle to speak for you too,’ Frankie said. ‘He’ll know your family for they were neighbours in Donegal and then Mammy helped when you first came over and my mother and yours are as thick as thieves now.’

‘We would appreciate it,’ Finbarr said. ‘See how the land lies when you get over there.’

‘Yes,’ Frankie said. ‘I won’t forget. It will be nice for me to see a familiar face anyway. I’ll write.’

So Frankie left a few days later. His mother cried copious tears and his siblings sniffled audibly. Even Mick’s voice was husky and even Frankie was struggling with his emotions, and he hugged his family and shook hands with all the well-wishers gathered to wish him God speed.

‘It will break my heart if Mammy is as upset as Norah was when we go,’ Colm said.

‘She will be,’ Finbarr said. ‘Worse maybe for there are two of us. But however sad she is, remember we are not just thinking about this for ourselves alone but also for Mammy and the others. All she has coming in now is what Daddy brings in and a pittance from Gerry and Barry’s apprenticeship money, and Gerry will be out on his ear before long too.’

‘Yeah I suppose.’

‘We need to leave, Colm, and go as far as America if things are as good as Frankie’s uncle says. The life we have now is no life at all, and even worse, we have no future to look forward to.’

It was sometime later Frankie wrote the promised letter and told them things were just fine and dandy for him in America and he was looking forward to them joining him. The even better news was that knowing the family personally from when they all lived in Donegal, their uncle was not only willing to sponsor them but loan them the £10 each needed for the assisted passage tickets, which would be easy to pay back from the good wages they’d be earning over there. Finbarr let his breath out in a sigh of utter relief, for he hadn’t known how they were going to raise the money for the fare, and this generous man was coming to their aid. All they had to do now was tell their parents and he thought that was better done sooner rather than later and give them time, particularly their mother, to come to terms with it.

If Finbarr and Colm thought Norah Docherty was upset when Frankie left, that was before they had seen their mother’s distress, for she was almost hysterical with grief. Never in her wildest dreams had she thought her sons would do what Frankie Docherty did and leave everything behind and travel to another continent entirely. She thought if nothing else, financial constraints would prevent them, for they would never raise the £10 needed to avail themselves of the assisted passage scheme. Aiden had paid for his nephew and it appeared he was prepared to loan her two sons the money needed and sponsor them too.

‘We have no life here, Mammy,’ Finbarr cried. ‘There is no future for us, our lives are dribbling away.’

Mary continued to cry, but Matt had listened to his sons. Finbarr had a point, he realized, for he was twenty-four now and Colm twenty-three. They should be working at a job of some sort and have money in their pockets for a pint or two now and then, go to the match if they had a mind, court a girl perhaps, and all they could see in front of them were years of the same struggle. There was no light at the end of the tunnel because they were unable to procure some meaningful employment, so Matt’s wage added together with a minute portion from his two sons still at the foundry had to keep them all. It was only Mary’s ability to make a sixpence do the work of a shilling that stopped them from starving altogether.

The situation couldn’t go on however, especially when there was every likelihood of the situation worsening when Gerry finished his apprenticeship in a year or two and subsequently Barry. His sons had the means of alleviating things for them and securing a future for themselves. It was bad that this involved them leaving home to move so far away but he didn’t see any alternative. Though he knew he would be heart-sore to lose them, for the good of them all it had to be.

Finbarr and Colm had their arms around their mother saying they were sorry and urging her not to upset herself, and her tears had changed to gulping sobs, and Matt waited till he was totally calm and then told Mary quietly the thoughts that had been tumbling around his head. As a pang of anguish swept over Mary’s face Colm moved away so Matt could hold Mary’s arm. Neither Finbarr nor Colm had been aware of Matt’s thoughts and the fact that he had listened to them and understood their concerns meant a great deal since the one person their mother listened to and took heed of was Matt.

‘But America, Matt,’ Mary wailed. ‘It’s so far away. We’ll never see them again.’

Matt gave a slight shake of his head. ‘We might not and there will be a part of my heart that will go with them, but we can be content, thinking that we have given them the potential for a full and happy life.’

Mary was still silent so Matt went on. ‘We left our native shores for a better life, remember.’

‘We only crossed a small stretch of water though.’

‘Never mind how long or short the journey was. We came for a better life,’ Matt said. ‘And for a time achieved it, but the system failed our boys and they are on the scrapheap. They want better than this and who can blame them? And if they have to go to America to achieve it, so be it.’

Mary gave a brief nod. Though tears shone in her eyes and she was unable to speak, she knew she had no right to deny a better life to her sons.