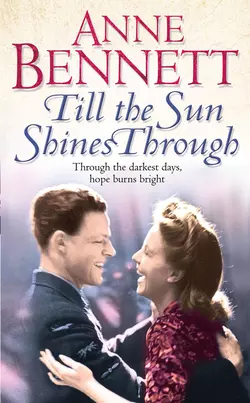

Till the Sun Shines Through

Anne Bennett

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 673.85 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A family is divided when its favourite daughter is forced to flee rural Ireland and to seek her living in war-torn Birmingham.Bridie McCarthy loves her family’s farm in the remotest part of Donegal, even though she’s forced to work hard when all of her siblings leave home. She can’t bear to let down her beloved parents – until a horrible act of violence gives her no option but to run away. She turns to the one person she can trust – big sister Mary, now settled with a family of her own in Birmingham.Life here couldn’t be more different, but slowly Bridie comes to see the good side of a busy city, and begins to regain her confidence. But fate has more trouble in store, as World War Two looms, threatening everything she’s fought so hard to win.