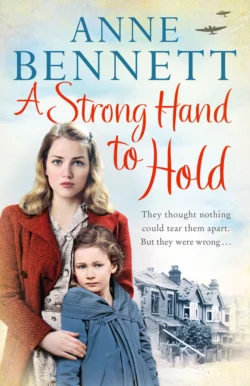

A Strong Hand to Hold

Anne Bennett

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 384.72 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A heartbreaking tale of love and loss in a time of war, perfect for fans of Katie Flynn and Annie Groves.Jenny O’Leary is devastated one morning in 1940 when she receives a telegram giving her the dreadful news that one of her brothers has been killed in action. Grief threatens to engulf her, but as an ARP warden, tending to Birmingham’s injured after the nightly raids, she is well-used to the suffering that thousands are enduring every day.Linda Prosser is just twelve years old and desperately close to her mother and two tiny brothers. As the bombs drop around them one fateful night, Linda takes a risk which has disastrous consequences. Terrified, and buried beneath a mass of debris after her home takes a direct hit, it is Jenny who crawls through the wreckage of the house to rescue her.So begins a friendship which is last through the years. But when Linda falls in love with a man that Jenny despises, she is faced with sacrificing her future happiness for the friend who has given her everything…