Of Lions and Unicorns: A Lifetime of Tales from the Master Storyteller

Michael Morpurgo

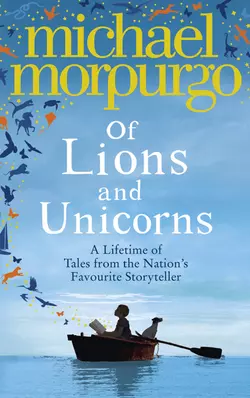

A lifetime of tales from the nation’s favourite storyteller, and award-winning author of WAR HORSE – the perfect gift for any book-lover.The most comprehensive and definitive Michael Morpurgo collection ever, this gorgeous edition features twenty-five enchanting short stories by the nation’s favourite storyteller – as well as extracts from twenty-five of his best-loved novels.Divided into five parts – covering war, animals, memory, the sea and folk tales – this timeless treasury spans the whole of Michael Morpurgo’s glittering literary career.Each of the five parts also features a full page illustration by the illustrators Michael has worked most closely with in the course of his writing life: Michael Foreman, Quentin Blake, Christian Birmingham, Emma Chichester-Clark and Peter Bailey. With such beautiful illustrations and such a wealth of extraordinary stories, don’t miss this stunning treat for collectors and fans alike.

For all our grandchildren.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u13b7d5db-eb81-5a18-a4d5-d4b2bd91aa92)

Title Page (#u5045e8d3-5aeb-52ac-a179-625153a87540)

Dedication (#u4ee88180-27f8-5f50-b66c-8fa76a0f23a2)

ONLY REMEMBERED (#udacef11a-18a1-5a7e-ae03-0b7a32953276)

My Father is a Polar Bear (#ua47ae692-b57e-5589-b716-160c32ff71e7)

Meeting Cézanne (#u39d63190-e8e9-5ab3-be42-fe13b8694f92)

Muck and Magic (#u9ecb2b58-9244-5f41-993d-a60135bf5249)

Homecoming (#uec984463-da53-57b3-96ae-58a147e38bd2)

My One and Only Great Escape (#u452193cd-18c1-56ea-a03d-02922bd804dd)

A Medal for Leroy (#u7e04b92e-bc9f-5571-88cb-86cb938e3abb)

The Amazing Story of Adolphus Tips (#u16b4c10b-0949-56b0-9afe-b9d6219a55c2)

Billy the Kid (#u8753f1aa-f0b4-5d05-b2a3-47b5dc172ed1)

The Wreck of the Zanzibar (#u3675541e-635a-5131-990e-176d5b4ac3d1)

Farm Boy (#u3327c119-f2c0-58cf-86d8-2b6ef9c1ba28)

NOT JUST A SHAGGY DOG STORY (#u562d7f9a-b57c-5ec5-ba3f-5dbc54b51372)

The Silver Swan (#ud1466459-e62e-5fd8-9da7-27b64480720d)

It’s a Dog’s Life (#u5ead8a12-1a7c-5740-a4f0-4ea203496e03)

Didn’t We Have a Lovely Time? (#ufb0f318c-9281-592b-8066-965e231c0a9a)

The Rainbow Bear (#litres_trial_promo)

Conker (#litres_trial_promo)

The Butterfly Lion (#litres_trial_promo)

Running Wild (#litres_trial_promo)

The Dancing Bear (#litres_trial_promo)

Born to Run (#litres_trial_promo)

The Last Wolf (#litres_trial_promo)

THE PITY AND THE SHAME (#litres_trial_promo)

Half a Man (#litres_trial_promo)

What Does it Feel Like? (#litres_trial_promo)

The Mozart Question (#litres_trial_promo)

The Best Christmas Present in the World (#litres_trial_promo)

For Carlos, a Letter from Your Father (#litres_trial_promo)

Shadow (#litres_trial_promo)

War Horse (#litres_trial_promo)

Private Peaceful (#litres_trial_promo)

An Elephant in the Garden (#litres_trial_promo)

The Kites are Flying (#litres_trial_promo)

Friend or Foe (#litres_trial_promo)

THE LONELY SEA AND THE SKY (#litres_trial_promo)

The Giant’s Necklace (#litres_trial_promo)

This Morning I Met a Whale (#litres_trial_promo)

The Saga of Ragnar Erikson (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Gone to Sea’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Dolphin Boy (#litres_trial_promo)

Alone on a Wide, Wide Sea (#litres_trial_promo)

Why the Whales Came (#litres_trial_promo)

Kaspar, Prince of Cats (#litres_trial_promo)

Kensuke’s Kingdom (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Olly (#litres_trial_promo)

TALES TOLD AND NEW (#litres_trial_promo)

Cockadoodle-doo, Mr Sultana! (#litres_trial_promo)

Aesop’s Fables (#litres_trial_promo)

Gentle Giant (#litres_trial_promo)

On Angel Wings (#litres_trial_promo)

The Best of Times (#litres_trial_promo)

Pinocchio (#litres_trial_promo)

The Pied Piper of Hamelin (#litres_trial_promo)

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (#litres_trial_promo)

Hansel and Gretel (#litres_trial_promo)

Beowulf (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography of Michael Morpurgo’s Works (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Illustrators (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_c24f053b-4e56-5936-85cf-89120b91e91a)

(#ulink_92611775-d5c0-51f9-bd03-58507d7fda27)

This story is a tissue of truth – mostly. As with many of my stories, I have woven truths together and made from them a truth stranger than fiction. My father was a polar bear – honestly.

racking down a polar bear shouldn’t be that difficult. You just follow the pawprints – easy enough for any competent Innuit. My father is a polar bear. Now if you had a father who was a polar bear, you’d be curious, wouldn’t you? You’d go looking for him. That’s what I did, I went looking for him, and I’m telling you he wasn’t at all easy to find.

In a way I was lucky, because I always had two fathers. I had a father who was there – I called him Douglas – and one who wasn’t there, the one I’d never even met – the polar bear one. Yet in a way he was there. All the time I was growing up he was there inside my head. But he wasn’t only in my head, he was at the bottom of our Start-Rite shoebox, our secret treasure box, with the rubber bands round it, which I kept hidden at the bottom of the cupboard in our bedroom. So how, you might ask, does a polar bear fit into a shoebox? I’ll tell you.

My big brother Terry first showed me the magazine under the bedclothes, by torchlight, in 1948 when I was five years old. The magazine was called Theatre World. I couldn’t read it at the time, but he could. (He was two years older than me, and already mad about acting and the theatre and all that – he still is.) He had saved up all his pocket money to buy it. I thought he was crazy. “A shilling! You can get about a hundred lemon sherbets for that down at the shop,” I told him

Terry just ignored me and turned to page twenty-seven. He read it out: “The Snow Queen, a dramat—something or other – of Hans Andersen’s famous story, by the Young Vic Company.” And there was a large black and white photograph right across the page – a photograph of two fierce-looking polar bears baring their teeth and about to eat two children, a boy and a girl, who looked very frightened.

“Look at the polar bears,” said Terry. “You see that one on the left, the fatter one? That’s our dad, our real dad. It says his name and everything – Peter Van Diemen. But you’re not to tell. Not Douglas, not even Mum, promise?”

“My dad’s a polar bear?” I said. As you can imagine I was a little confused.

“Promise you won’t tell,” he went on, “or I’ll give you a Chinese burn.”

Of course I wasn’t going to tell, Chinese burn or no Chinese burn. I was hardly going to go to school the next day and tell everyone that I had a polar bear for a father, was I? And I certainly couldn’t tell my mother, because I knew she never liked it if I ever asked about my real father. She always insisted that Douglas was the only father I had. I knew he wasn’t, not really. So did she, so did Terry, so did Douglas. But for some reason that was always a complete mystery to me, everyone in the house pretended that he was.

Some background might be useful here. I was born, I later found out, when my father was a soldier in Baghdad during the Second World War. (You didn’t know there were polar bears in Baghdad, did you?) Sometime after that my mother met and fell in love with a dashing young officer in the Royal Marines called Douglas Macleish. All this time, evacuated to the Lake District away from the bombs, blissfully unaware of the war and Douglas, I was learning to walk and talk and do my business in the right place at the right time. So my father came home from the war to discover that his place in my mother’s heart had been taken. He did all he could to win her back. He took her away on a week’s cycling holiday in Suffolk to see if he could rekindle the light of their love. But it was hopeless. By the end of the week they had come to an amicable arrangement. My father would simply disappear, because he didn’t want to “get in the way”. They would get divorced quickly and quietly, so that Terry and I could be brought up as a new family with Douglas as our father. Douglas would adopt us and give us Macleish as our surname. All my father insisted upon was that Terry and I should keep Van Diemen as our middle name. That’s what happened. They divorced. My father disappeared, and at the age of three I became Andrew Van Diemen Macleish. It was a mouthful then and it’s a mouthful now.

So Terry and I had no actual memories of our father whatsoever. I do have vague recollections of standing on a railway bridge somewhere near Earls Court in London, where we lived, with Douglas’s sister – Aunty Betty, as I came to know her – telling us that we had a brand new father who’d be looking after us from now on. I was really not that concerned, not at the time. I was much more interested in the train that was chuffing along under the bridge, wreathing us in a fog of smoke.

My first father, my real father, my missing father, became a taboo person, a big hush hush taboo person that no one ever mentioned, except for Terry and me. For us he soon became a sort of secret phantom father. We used to whisper about him under the blankets at night. Terry would sometimes go snooping in my mother’s desk and he’d find things out about him. “He’s an actor,” Terry told me one night. “Our dad’s an actor, just like Mum is, just like I’m going to be.”

It was only a couple of weeks later that he brought the theatre magazine home. After that we’d take it out again and look at our polar bear father. It took some time, I remember, before the truth of it dawned on me – I don’t think Terry can have explained it very well. If he had, I’d have understood it much sooner – I’m sure I would. The truth, of course – as I think you might have guessed by now – was that my father was both an actor and a polar bear at one and the same time.

Douglas went out to work a lot and when he was home he was a bit silent, so we didn’t really get to know him. But we did get to know Aunty Betty. Aunty Betty simply adored us, and she loved giving us treats. She wanted to take us on a special Christmas treat, she said. Would we like to go to the zoo? Would we like to go to the pantomime? There was Dick Whittington or Puss in Boots. We could choose whatever we liked.

Quick as a flash, Terry said, “The Snow Queen. We want to go to The Snow Queen.”

So there we were a few days later, Christmas Eve 1948, sitting in the stalls at a matinee performance of The Snow Queen at the Young Vic theatre, waiting, waiting for the moment when the polar bears come on. We didn’t have to wait for long. Terry nudged me and pointed, but I already knew which polar bear my father had to be. He was the best one, the snarliest one, the growliest one, the scariest one. Whenever he came on he really looked as if he was going to eat someone, anyone. He looked mean and hungry and savage, just the way a polar bear should look.

I have no idea whatsoever what happened in The Snow Queen. I just could not take my eyes off my polar bear father’s curling claws, his slavering tongue, his killer eyes. My father was without doubt the finest polar bear actor the world had ever seen. When the great red curtains closed at the end and opened again for the actors to take their bows, I clapped so hard that my hands hurt. Three more curtain calls and the curtains stayed closed. The safety curtain came down and my father was cut off from me, gone, gone for ever. I’d never see him again.

Terry had other ideas. Everyone was getting up, but Terry stayed sitting. He was staring at the safety curtain as if in some kind of trance. “I want to meet the polar bears,” he said quietly.

Aunty Betty laughed. “They’re not bears, dear, they’re actors, just actors, people acting. And you can’t meet them, it’s not allowed.”

“I want to meet the polar bears,” Terry repeated. So did I, of course, so I joined in. “Please, Aunty Betty,” I pleaded. “Please.”

“Don’t be silly. You two, you do get some silly notions sometimes. Have a Choc Ice instead. Get your coats on now.” So we each got a Choc Ice. But that wasn’t the end of it.

We were in the foyer caught in the crush of the crowd when Aunty Betty suddenly noticed that Terry was missing. She went loopy. Aunty Betty always wore a fox stole, heads still attached, round her shoulders. Those poor old foxes looked every bit as pop-eyed and frantic as she did, as she plunged through the crowd, dragging me along behind her and calling for Terry.

Gradually the theatre emptied. Still no Terry. There was quite a to-do, I can tell you. Policemen were called in off the street. All the programme sellers joined in the search, everyone did. Of course, I’d worked it out. I knew exactly where Terry had gone, and what he was up to. By now Aunty Betty was sitting down in the foyer and sobbing her heart out. Then, cool as a cucumber, Terry appeared from nowhere, just wandered into the foyer. Aunty Betty crushed him to her, in a great hug. Then she went loopy all over again, telling him what a naughty, naughty boy he was, going off like that. “Where were you? Where have you been?” she cried.

“Yes, young man,” said one of the policemen. “That’s something we’d all like to know as well.”

I remember to this day exactly what Terry said, the very words: “Jimmy riddle. I just went for a jimmy riddle.” For just a moment he even had me believing him. What an actor! Brilliant.

We were on the bus home, right at the front on the top deck where you can guide the bus round corners all by yourself – all you have to do is steer hard on the white bar in front of you. Aunty Betty was sitting a couple of rows behind us. Terry made quite sure she wasn’t looking. Then, very surreptitiously, he took something out from under his coat and showed me. The programme. Signed right across it were these words, which Terry read out to me:

“To Terry and Andrew,

With love from your polar bear father, Peter. Keep happy.”

Night after night I asked Terry about him, and night after night under the blankets he’d tell me the story again, about how he’d gone into the dressing-room and found our father sitting there in his polar bear costume with his head off (if you see what I mean), all hot and sweaty. Terry said he had a very round, very smiley face, and that he laughed just like a bear would laugh, a sort of deep bellow of a laugh – when he’d got over the surprise that is. Terry described him as looking like “a giant pixie in a bearskin”.

For ever afterwards I always held it against Terry that he never took me with him that day down to the dressing-room to meet my polar bear father. I was so envious. Terry had a memory of him now, a real memory. And I didn’t. All I had were a few words and a signature on a theatre programme from someone I’d never even met, someone who to me was part polar bear, part actor, part pixie – not at all easy to picture in my head as I grew up.

Picture another Christmas Eve fourteen years later. Upstairs, still at the bottom of my cupboard, my polar bear father in the magazine in the Start-Rite shoebox; and with him all our accumulated childhood treasures: the signed programme, a battered champion conker (a sixty-fiver!), six silver ball-bearings, four greenish silver threepenny bits (Christmas pudding treasure trove), a Red Devil throat pastille tin with three of my milk teeth cushioned in yellowy cotton wool, and my collection of twenty-seven cowrie shells gleaned from many summers from the beach on Samson in the Scilly Isles. Downstairs, the whole family were gathered in the sitting-room: my mother, Douglas, Terry and my two sisters (half-sisters, really, but of course no one ever called them that), Aunty Betty, now married, with twin daughters, my cousins, who were truly awful – I promise you. We were decorating the tree, or rather the twins were fighting over every single dingly-dangly glitter ball, every strand of tinsel. I was trying to fix up the Christmas tree lights, which, of course, wouldn’t work – again – whilst Aunty Betty was doing her best to avert a war by bribing the dreadful cousins away from the tree with a Mars bar each. It took a while, but in the end she got both of them up on to her lap, and soon they were stuffing themselves contentedly with Mars bars. Blessed peace.

This was the very first Christmas we had had the television. Given half a chance we’d have had it on all the time. But, wisely enough I suppose, Douglas had rationed us to just one programme a day over Christmas. He didn’t want the Christmas celebrations interfered with by “that thing in the corner”, as he called it. By common consent, we had chosen the Christmas Eve film on the BBC at five o’clock.

Five o’clock was a very long time coming that day, and when at last Douglas got up and turned on the television, it seemed to take for ever to warm up. Then, there it was on the screen: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. The half-mended lights were at once discarded, the decorating abandoned, as we all settled down to watch in rapt anticipation. Maybe you know the moment: Young Pip is making his way through the graveyard at dusk, mist swirling around him, an owl screeching, gravestones rearing out of the gloom, branches like ghoulish fingers whipping at him as he passes, reaching out to snatch him. He moves through the graveyard timorously, tentatively, like a frightened fawn. Every snap of a twig, every barking fox, every aarking heron sends shivers into our very souls.

Suddenly, a face! A hideous face, a monstrous face, looms up from behind a gravestone. Magwitch, the escaped convict, ancient, craggy and crooked, with long white hair and a straggly beard. A wild man with wild eyes, the eyes of a wolf.

The cousins screamed in unison, long and loud, which broke the tension for all of us and made us laugh. All except my mother.

“Oh my God,” she breathed, grasping my arm. “That’s your father! It’s him. It’s Peter.”

All the years of pretence, the whole long conspiracy of silence were undone in that one moment. The drama on the television paled into sudden insignificance. The hush in the room was palpable.

Douglas coughed. “I think I’ll fetch some more logs,” he said. And my two half-sisters went out with him, in solidarity I think. So did Aunty Betty and the twins; and that left my mother, Terry and me alone together.

I could not take my eyes off the screen. After a while I said to Terry, “He doesn’t look much like a pixie to me.”

“Doesn’t look much like a polar bear either,” Terry replied. At Magwitch’s every appearance I tried to see through his make-up (I just hoped it was make-up!) to discover how my father really looked. It was impossible. My polar bear father, my pixie father had become my convict father.

Until the credits came up at the end my mother never said a word. Then all she said was, “Well, the potatoes won’t peel themselves, and I’ve got the Brussels sprouts to do as well.” Christmas was a very subdued affair that year, I can tell you.

They say you can’t put a genie back in the bottle. Not true. No one in the family ever spoke of the incident afterwards – except Terry and me of course. Everyone behaved as if it had never happened. Enough was enough. Terry and I decided it was time to broach the whole forbidden subject with our mother, in private. We waited until the furore of Christmas was over, and caught her alone in the kitchen one evening. We asked her point blank to tell us about him, our ‘first’ father, our ‘missing’ father.

“I don’t want to talk about him,” she said. She wouldn’t even look at us. “All I know is that he lives somewhere in Canada now. It was another life. I was another person then. It’s not important.” We tried to press her, but that was all she would tell us.

Soon after this I became very busy with my own life, and for some years I thought very little about my convict father, my polar bear father. By the time I was thirty I was married with two sons, and was a teacher trying to become a writer, something I had never dreamt I could be.

Terry had become an actor, something he had always been quite sure he would be. He rang me very late one night in a high state of excitement. “You’ll never guess,” he said. “He’s here! Peter! Our dad. He’s here, in England. He’s playing in Henry IV, Part II in Chichester. I’ve just read a rave review. He’s Falstaff. Why don’t we go down there and give him the surprise of his life?”

So we did. The next weekend we went down to Chichester together. I took my family with me. I wanted them to be there for this. He was a wonderful Falstaff, big and boomy, rumbustious and raunchy, yet full of pathos. My two boys (ten and eight) kept whispering at me every time he came on. “Is that him? Is that him?” Afterwards we went round to see him in his dressing-room. Terry said I should go in first, and on my own. “I had my turn a long time ago, if you remember,” he said. “Best if he sees just one of us to start with, I reckon.”

My heart was in my mouth. I had to take a very deep breath before I knocked on that door. “Enter.” He sounded still jovial, still Falstaffian. I went in.

He was sitting at his dressing-table in his vest and braces, boots and britches, and humming to himself as he rubbed off his make-up. We looked at each other in the mirror. He stopped humming, and swivelled round to face me. For some moments I just stood there looking at him. Then I said, “Were you a polar bear once, a long time ago in London?”

“Yes.”

“And were you once the convict in Great Expectations on the television?”

“Yes.”

“Then I think I’m your son,” I told him.

There was a lot of hugging in his dressing-room that night, not enough to make up for all those missing years, maybe. But it was a start.

My mother’s dead now, bless her heart, but I still have two fathers. I get on well enough with Douglas, I always have done in a detached sort of way. He’s done his best by me, I know that; but in all the years I’ve known him he’s never once mentioned my other father. It doesn’t matter now. It’s history best left crusted over I think.

We see my polar bear father – I still think of him as that – every year or so, whenever he’s over from Canada. He’s well past eighty now, still acting for six months of the year – a real trouper. My children and my grandchildren always call him Grandpa Bear because of his great bushy beard (the same one he grew for Falstaff!), and because they all know the story of their grandfather, I suppose.

Recently I wrote a story about a polar bear. I can’t imagine why. He’s upstairs now reading it to my smallest granddaughter. I can hear him a-snarling and a-growling just as proper polar bears do. Takes him back, I should think. Takes me back, that’s for sure.

(#ulink_b0aac131-1df4-539c-b750-1a7f7dcb2577)

don’t remember why my mother had to go into hospital. I’m not sure she ever told me. She did explain that after the operation she would be needing a month of complete rest. This is why she had had to arrange for me to go and stay with Aunt Mathilde, my mother’s older sister, in her house down in the south, in Provence.

I’d never been to Provence, but I had met my Aunt Mathilde a few times when she’d come to see us in our little apartment in Paris. I remembered her being big and bustling, filling the place with her bulk and forever hugging and kissing me, which I never much cared for. She’d pinch my cheek and tell me I was a “beautiful little man”. But she’d always bring us lots of crystallised fruits, so I could forgive her everything else.

I was ten years old and had never been parted from my mother. I’d only been out of Paris once for a holiday by the sea in Brittany. I told her I didn’t want to be sent away. I told her time and time again, but it was no use.

“You’ll be fine, Yannick,” she insisted. “You like Aunt Mathilde, don’t you? And Uncle Bruno is very funny. He has a moustache that prickles like a hedgehog. And you’ve never even met your cousin Amandine. You’ll have a lovely time. Spring in Provence. It’ll be a paradise for you, I promise. Crystallised fruit every day!”

She did all she could to convince me. More than once she read me Jean Giono’s story “The Man Who Planted Trees”, the story of an old shepherd set in the high hills of Provence. She showed me a book of paintings by Paul Cézanne, paintings, she told me, of the countryside outside Aix-en-Provence, very close to Aunt Mathilde’s home. “Isn’t it beautiful, Yannick?” she breathed as she turned the pages. “Cézanne loved it there, and he’s the greatest painter in the world. Remember that.”

A city boy all my life, the paintings really did look like the paradise my mother had promised me. So by the time she put me on the train at the Gare de Lyon I was really looking forward to it. Blowing kisses to her for the last time out of the train window, I think the only reason I didn’t cry was because I was quite sure by now that I was indeed going to the most wonderful place in the world, the place where Cézanne, the greatest painter in the world, painted his pictures, where Jean Giono’s old shepherd walked the high hills planting his acorns to make a forest.

Aunt Mathilde met me off the train and enveloped me in a great bear hug and pinched my cheek. It wasn’t a good start. She introduced me to my cousin Amandine, who barely acknowledged my existence, but who was very beautiful. On the way to the car, following behind Aunt Mathilde, Amandine told me at once that she was fourteen and much older than I was and that I had to do what she said. I loved her at once. She wore a blue and white gingham dress, and she had a ponytail of chestnut hair that shone in the sunshine. She had the greenest eyes I’d ever seen. She didn’t smile at me, though. I so hoped that one day she would.

We drove out of town to Vauvenargues, Aunt Mathilde talking all the way. I was in the back seat of the Deux Chevaux and couldn’t hear everything, but I did pick up enough to understand that Uncle Bruno ran the village inn. He did the cooking and everyone helped. “And you’ll have to help too,” Amandine added without even turning to look at me. Everywhere about me were the gentle hills and folding valleys, the little houses and dark pointing trees I’d seen in Cézanne’s paintings. Uncle Bruno greeted me wrapped in his white apron. Mother was right. He did have a huge hedgehog of a moustache that prickled when he kissed me. I liked him at once.

I had my own little room above the restaurant, looking out over a small back garden. An almond tree grew there, the pink blossoms brushing against my window pane. Beyond the tree were the hills, Cézanne’s hills. And after supper they gave me a crystallised fruit, apricot, my favourite. All that and Amandine too. I could not have been happier.

It became clear to me very quickly that whilst I was made to feel very welcome and part of the family – Aunt Mathilde was always showing me off proudly to her customers as her nephew, “her beautiful little man from Paris” – I was indeed expected to do what everyone else did, to do my share of the work in the inn. Uncle Bruno was almost always busy in the kitchen. He clanked his pots and sang his songs, and would waggle his moustache at me whenever I went in, which always made me giggle. He was happiest in his kitchen, I could tell that. Aunt Mathilde bustled and hustled; she liked things to be just so. She greeted every customer like a long-lost friend. She was the heart and soul of the place. As for Amandine, she took me in hand at once, and explained that I’d be working with her, that she’d been asked to look after me. She did not mince her words. I could not expect to spend my summer with them, she said, and not earn my keep.

She put me to work at once in the restaurant, laying tables, clearing tables, cutting bread, filling up breadbaskets, filling carafes of water, making sure there was enough wood on the fire in the evenings, and washing up, of course. After just one day I was exhausted. Amandine told me I had to learn to work harder and faster, but she did kiss me goodnight before I went upstairs, which was why I did not wash my face for days afterwards.

At least I had the mornings to myself. I made the best of the time I had, exploring the hills, stomping through the woods, climbing trees. Amandine never came with me. She had lots of friends in the village, bigger boys who stood about with their thumbs hooked into the pockets of their blue jeans, and roared around on motor scooters with Amandine clinging on behind, her hair flying. These were the boys she smiled at, the boys she laughed with. I was more sad than jealous, I think; I simply loved her more than ever.

There was a routine to the restaurant work. As soon as customers had left, Amandine would take away the wine glasses and the bottles and the carafes. The coffee cups and cutlery were my job. She would deal with the ashtrays, whilst I scrunched up the paper tablecloths and threw them on the fire. Then we’d lay the table again as quickly as possible for the next guests. I worked hard because I wanted to please Amandine, and to make her smile at me. She never did.

She laughed at me, though. She was in the village street one morning, her motor-scooter friends gathered adoringly all around her, when she turned and saw me. They all did. Then she was laughing and they were too. I walked away knowing I should be hating her, but I couldn’t. I longed all the more for her smile. I longed for her just to notice me. With every day she didn’t I became more and more miserable, sometimes so wretched I would cry myself to sleep at nights. I lived for my mother’s letters and for my mornings walking the hills that Cézanne had painted, gathering acorns from the trees Jean Giono’s old shepherd had planted. Here, away from Amandine’s indifference, I could be happy for a while and dream my dreams. I thought that one day I might like to live in these hills myself, and be a painter like Cézanne, the greatest painter in the world, or maybe a wonderful writer like Jean Giono.

I think Uncle Bruno sensed my unhappiness, because he began to take me more and more under his wing. He’d often invite me into his kitchen and let me help him cook his soupe au pistou or his poulet romarin with pommes dauphinoises and wild leeks. He taught me to make chocolate mousse and crème brûlée, and before I left he’d always waggle his moustache for me and give me a crystallised apricot. But I dreaded the restaurant now, dreaded having to face Amandine again and endure the silence between us. I dreaded it, but would not have missed it for the world. I loved her that much.

Then one day a few weeks later I had a letter from my mother saying she was much better now, that Aunt Mathilde would put me on the train home in a few days’ time. I was torn. Of course I yearned to be home again, to see my mother, but at the same time I did not want to leave Amandine.

That evening Amandine told me I had to do everything just right because their best customer was coming to dine with some friends. He lived in the chateau in the village, she said, and was very famous; but when I asked what he was famous for, she didn’t seem interested in telling me.

“Questions, always questions,” she tutted. “Go and fetch in the logs.”

Whoever he was, he looked ordinary enough to me, just an old man with not much hair. But he ate one of the crème brûlées I’d made and I felt very pleased a famous man had eaten one of my crème brûlées. As soon as he and his friends had gone we began to clear the table. I pulled the paper tablecloth off as usual, and as usual scrunched it up and threw it on the fire. Suddenly Amandine was rushing past me. For some reason I could not understand at all she grabbed the tongs and tried to pull the remnants of the burning paper tablecloth out of the flames, but it was already too late. Then she turned on me.

“You fool!” she shouted. “You little fool!”

“What?” I said.

“That man who just left. If he likes his meal he does a drawing on the tablecloth for Papa as a tip, and you’ve only gone and thrown it on the fire. He’s only the most famous painter in the world. Idiot! Imbecile!” She was in tears now. Everyone in the restaurant had stopped eating and gone quite silent.

Then Uncle Bruno was striding towards us, not his jolly self at all. “What is it?” he asked Amandine. “What’s the matter?”

“It was Yannick, Papa,” she cried. “He threw it on the fire, the tablecloth, the drawing.”

“Had you told him about it, Amandine?” Uncle Bruno asked. “Did Yannick know about how sometimes he sketches something on the tablecloth, and how he leaves it behind for us?”

Amandine looked at me, her cheeks wet with tears. I thought she was going to lie. But she didn’t.

“No, Papa,” she said, lowering her head.

“Then you shouldn’t be blaming him, should you, for something that was your fault. Say sorry to Yannick now.” She mumbled it but she never raised her eyes. Uncle Bruno put his arm round me and walked me away. “Never mind, Yannick,” he said. “He said he particularly liked his crème brûlée. That’s probably why he left the drawing. You made the crème brûlée, didn’t you? So it was for you really he did it. Always look on the bright side. For a moment you had in your hands a drawing done for you and your crème brûlée by the greatest painter in the world. That’s something you’ll never forget.”

Later on as I came out of the bathroom I heard Amandine crying in her room. I hated to hear her crying, so I knocked on the door and went in. She was lying curled up on her bed hugging her pillow.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I didn’t mean to upset you.” She had stopped crying by now.

“It wasn’t your fault, Yannick,” she said, still sniffing a bit. “It’s just that I hate it when Papa’s cross with me. He hardly ever is, only when I’ve done something really bad. I shouldn’t have blamed you. I’m sorry.”

And then she smiled at me. Amandine smiled at me!

I lay awake all night, my mind racing. Somehow I was going to put it all right again. I was going to make Amandine happy. By morning I had worked out exactly what I had to do and how to do it, even what I was going to say when the time came.

That morning, I didn’t go for my walk in the hills. Instead I made my way down through the village towards the chateau. I’d often wondered what it was like behind those closed gates. Now I was going to find out. I waited till there was no one about, no cars coming. I climbed the gates easily enough, then ran down through the trees. And there it was, immense and forbidding, surrounded by forest on all sides. And there he was, the old man with very little hair I had seen the night before. He was sitting alone in the sunshine at the foot of the steps in front of the chateau, and he was sketching. I approached as silently as I could across the grass, but somehow I must have disturbed him. He looked up, shading his eyes against the sun. “Hello, young man,” he said. Now that I was this close to him I could see he was indeed old, very old, but his eyes were young and bright and searching.

“Are you Monsieur Cézanne?” I asked him. “Are you the famous painter?” He seemed a little puzzled at this, so I went on. “My mother says you are the greatest painter in the world.”

He was smiling now, then laughing. “I think your mother’s probably right,” he said. “You clearly have a wise mother, but what I’d like to know is why she let a young lad like you come wandering here on his own?”

As I explained everything and told him why I’d come and what I wanted, he looked at me very intently, his brow furrowing. “I remember you now, from last night,” he said, when I’d finished. “Of course I’ll draw another picture for Bruno. What would he like? No. Better still, what would you like?”

“I like sailing boats,” I told him. “Can you do boats?”

“I’ll try,” he replied with a smile.

It didn’t take him long. He drew fast, never once looking up. But he did ask me questions as he worked, about where I’d seen sailing boats, about where I lived in Paris. He loved Paris, he said, and he loved sailing boats too.

“There,” he said, tearing the sheet from his sketchbook and showing me. “What do you think?” Four sailing boats were racing over the sea out beyond a lighthouse, just as I’d seen them in Brittany. But I saw he’d signed it Picasso.

“I thought your name was Cézanne,” I said.

He smiled up at me. “How I wish it was,” he said sadly. “How I wish it was. Off you go now.”

I ran all the way back to the village, wishing all the time I’d told him that I was the one who had made the crème brûlée he’d liked so much. I found Amandine by the washing line, a clothes peg in her mouth. “I did it!” I cried breathlessly, waving the drawing at her. “I did it! To make up for the one I burned.”

Amandine took the peg out of her mouth and looked down at the drawing.

“That’s really sweet of you to try, Yannick,” she said. “But the thing is, it’s got to be done by him, by Picasso himself. It’s no good you drawing a picture and then just signing his name. It’s got to be by him or it’s not worth the money.”

I was speechless. Then as she turned away to hang up one of Uncle Bruno’s aprons, Aunt Mathilde came out into the garden with a basket of washing under her arm.

“Yannick’s been very kind, Maman,” Amandine said. “He’s done me a drawing. After what happened last night. It’s really good too.”

Aunt Mathilde had put down her washing and was looking at the drawing. “Bruno!” she called. “Bruno, come out here!” And Uncle Bruno appeared, his hands white with flour. “Look at this,” said Aunt Mathilde. “Look what Yannick did, and all by himself too.”

Bruno peered at it closely for a moment, then started to roar with laughter. “I don’t think so,” he said. “Yannick may be a genius with crème brûlée, but this is by Picasso, the great man himself. I promise you. Isn’t it, Yannick?”

So I told them the whole story. When I’d finished, Amandine came over and hugged me. She had tears in her eyes. I was in seventh heaven, and Uncle Bruno waggled his moustache and gave me six crystallised apricots. Unfortunately Aunt Mathilde hugged me too and pinched my cheek especially hard. I was the talk of the inn that night, and felt very proud of myself. But best of all Amandine came on my walk in the hills the next day and climbed trees with me and collected acorns, and held my hand all the way back down the village street, where everyone could see us, even the motor-scooter boys in their blue jeans.

They still have the boat drawing by Picasso hanging in the inn. Amandine runs the place now. It’s as good as ever. She married someone else, as cousins usually do. So did I. I’m a writer still trying to follow in Jean Giono’s footsteps. As for Cézanne, was my mother right? Is he the greatest painter in the world? Or is it Picasso? Who knows? Who cares? They’re both wonderful and I’ve met both of them – if you see what I’m saying.

(#ulink_548787f7-21e3-51aa-8410-b6f04fd879de)

Some years ago, we got to know Elisabeth Frink, a wonderful sculptor, particularly of horses, and a kind and generous person too. She became a great friend and ally in life. Sadly, she died all too young. Her very last work now hangs above the west door of Liverpool Cathedral. It is a Risen Christ.

am sometimes asked these days how I got started. I should love to be able to say that it was all because I had some dream, some vision, or maybe that I just studied very hard. None of this would really be true. I owe what I am, what I have become, what I do each day of my life, to a bicycle ride I took a long time ago now, when I was twelve years old – and also to a pile of muck, horse muck.

The bike was new that Christmas. It was maroon, and I remember it was called a Raleigh Wayfarer. It had all you could ever dream of in a bike – in those days. It had a bell, a dynamo lamp front and rear, five gears and a silver pump. I loved it instantly and spent every hour I could out riding it. And when I wasn’t riding it, I was polishing it.

We lived on the edge of town, so it was easy to ride off down Mill Lane past the estate, along the back of the soap factory where my father worked, and then out into the countryside beyond. How I loved it. In a car, you zoomed past so fast that the cows and the trees were only ever brief, blurred memories. On my bike I was close to everything for the first time. I felt the cold and the rain on my face. I mooed at the cows, and they looked up and blinked at me lazily. I shouted at the crows and watched them lift off cawing and croaking into the wind. But best of all, no one knew where I was – and that included me sometimes. I was always getting myself lost and coming back at dusk, late. I would brace myself for all the sighing and tutting and ticking off that inevitably followed. I bore it all stoically because they didn’t really mean it, and anyway it had all been worth it. I’d had a taste of real freedom and I wanted more of it.

After a while I discovered a circuit that seemed to be just about ideal. It was a two-hour run, not too many hills going up, plenty going down, a winding country lane that criss-crossed a river past narrow cottages where hardly anyone seemed to live, under the shadow of a church where sometimes I stopped and put flowers on the graves that everyone else seemed to have forgotten, and then along the three-barred iron fence where the horses always galloped over to see me, their tails and heads high, their ears pricked.

There were three of them: a massive bay hunter that looked down on me from a great height, a chubby little pony with a face like a chipmunk, and a fine-boned grey that flowed and floated over the ground with such grace and ease that I felt like clapping every time I saw her move. She made me laugh too because she often made rude, farty noises as she came trotting over to see me. I called her Peg after a flying horse called Pegasus that I’d read about in a book. The small one I called Chip, and the great bay, Big Boy. I’d cuddle them all, give each of them a sugar lump – two for Peg because she wasn’t as pushy as the other two – told them my troubles, cuddled them a little more and went on my way, always reluctantly.

I hated to leave them because I was on my way back home after that, back to homework, and the sameness of the house, and my mother’s harassed scurrying and my little brother’s endless tantrums. I lay in my room and dreamed of those horses, of Peg in particular. I pictured myself riding her bareback through flowery meadows, up rutty mountain passes, fording rushing streams where she’d stop to drink. I’d go to sleep at nights lying down on the straw with her, my head resting on her warm belly. But when I woke, her belly was always my pillow, and my father was in the bathroom next door, gargling and spitting into the sink, and there was school to face, again. But after school I’d be off on my bike and that was all that mattered to me. I gave up ballet lessons on Tuesdays. I gave up cello lessons on Fridays. I never missed a single day, no matter what the weather – rain, sleet, hail – I simply rode through it all, living for the moment when Peg would rest her heavy head on my shoulder and I’d hear that sugar lump crunching inside her great grinding jaw.

It was spring. I know that because there were daffodils all along the grass verge by the fence, and there was nowhere to lie my bike down on the ground without squashing them. So I leant it up against the fence and fished in my pocket for the sugar lumps. Chip came scampering over as he always did, and Big Boy wandered lazily up behind him, his tail flicking nonchalantly. But I saw no sign of Peg. When Big Boy had finished his sugar lump, he started chewing at the saddle of my bike and knocked it over. I was just picking it up when I saw her coming across the field towards me. She wore long green boots and a jersey covered in plants and stars, gold against the dark, deep blue of space. But what struck me most was her hair, the wild white curly mop of it, around her face that was somehow both old and young at the same time.

“Who are you?” she asked. It was just a straight question, not a challenge.

“Bonnie,” I replied.

“She’s not here,” said the woman.

“Where is she?”

“It’s the spring grass. I have to keep her inside from now on.”

“Why?”

“Laminitis. She’s fine all through the winter, eats all the grass she likes no trouble. But she’s only got to sniff the spring grass and it comes back. It heats the hoof, makes her lame.” She waved away the two horses and came closer, scrutinising me. “I’ve seen you before, haven’t I? You like horses, don’t you?” I smiled. “Me too,” she went on. “But they’re a lot of work.”

“Work?” I didn’t understand.

“Bring them in, put them out, groom them, pick out their feet, feed them, muck them out. I’m not as young as I was, Bonnie. You don’t want a job do you, in the stables? Be a big help. The grey needs a good long walk every day, and a good mucking out. Three pounds an hour, what do you say?”

Just like that. I said yes, of course. I could come evenings and weekends.

“I’ll see you tomorrow then,” she said. “You’ll need wellies. I’ve got some that should fit. You be careful on the roads now.” And she turned and walked away.

I cycled home that day singing my heart out and high as a kite. It was my first paying job, and I’d be looking after Peg. It really was a dream come true.

I didn’t tell anyone at home, nor at school. Where I went on my bike, what I did, was my own business, no one else’s. Besides there was always the chance that Father would stop me – you never knew with him. And I certainly didn’t want any of my school friends oaring in on this. At least two of them knew all about horses, or they said they did, and I knew they would never stop telling me the right way to do this or that. Best just to keep everything to myself.

To get to the house the next day – you couldn’t see it from the road – I cycled up a long drive through high trees that whispered at me. I had to weave around the pot-holes, bump over sleeping policemen, but then came out on to a smooth tarmac lane where I could freewheel downhill and hear the comforting tic-a-tic of my wheels beneath me.

I nearly came off when I first saw them. Everywhere in amongst the trees there were animals, but none of them moved. They just looked at me. There were wild boar, dogs, horses and gigantic men running through trees like hunters. But all were as still as statues. They were statues. Then I saw the stables on my right, Peg looking out at me, ears pricked and shaking her mane. Beyond the stables was a long house of flint and brick with a tiled roof, and a clock tower with doves fluttering around it.

The stable block was deserted. I didn’t like to call out, so I opened the gate and went over to Peg and stroked her nose. That was when I noticed a pair of wellies waiting by the door, and slipped into one of them was a piece of paper. I took it out and read:

Hope these fit. Take her for a walk down the tracks, not in the fields. She can nibble the grass, but not too much. Then muck out the stables. Save what dry straw you can – it’s expensive. When you’ve done, shake out half a bale in her stable – you’ll find straw and hay in the barn. She has two slices of hay in her rack. Don’t forget to fill up the water buckets.

It was not signed.

Until then I had not given it a single thought, but I had never led a horse or ridden a horse in all my life. Come to that, I hadn’t mucked out a stable either. Peg had a halter on her already, and a rope hung from a hook beside the stable. I put the wellies on – they were only a little too big – clipped on the rope, opened the stable door and led her out, hoping, praying she would behave. I need not have worried. It was Peg that took me for a walk. I simply stopped whenever she did, let her nibble for a while, and then asked her gently if it wasn’t time to move on. She knew the way, up the track through the woods, past the running men and the wild boar, then forking off down past the ponds where a bronze water buffalo drank without ever moving his lips. White fish glided ghostly under the shadow of his nose. The path led upwards from there, past a hen house where a solitary goose stretched his neck, flapped his wings and honked at us. Peg stopped for a moment, lifted her nose and wrinkled it at the goose who began preening himself busily. After a while I found myself coming back to the stable-yard gate and Peg led me in. I tied her up in the yard and set about mucking out the stables.

I was emptying the wheelbarrow on to the muck heap when I felt someone behind me. I turned round. She was older than I remembered her, greyer in the face, and more frail. She was dressed in jeans and a rough sweater this time, and seemed to be covered in white powder, as if someone had thrown flour at her. Even her cheeks were smudged with it. She glowed when she smiled.

“Where’s there’s muck there’s money, that’s what they say,” she laughed; and then she shook her head. “Not true, I’m afraid, Bonnie. Where there’s muck, there’s magic. Now that’s true.” I wasn’t sure what she meant by that. “Horse muck,” she went on by way of explanation. “Best magic in the world for vegetables. I’ve got leeks in my garden longer than, longer than …” She looked around her. “Twice as long as your bicycle pump. All the soil asks is that we feed it with that stuff, and it’ll do anything we want it to. It’s like anything, Bonnie, you have to put in more than you take out. You want some tea when you’ve finished?”

“Yes please.”

“Come up to the house then. You can have your money.” She laughed at that. “Maybe there is money in muck after all.”

As I watched her walk away, a small yappy dog came bustling across the lawn, ran at her and sprang into her arms. She cradled him, put him over her shoulder and disappeared into the house.

I finished mucking out the stable as quickly as I could, shook out some fresh straw, filled up the water buckets and led Peg back in. I gave her a goodbye kiss on the nose and rode my bike up to the house.

I found her in the kitchen, cutting bread.

“I’ve got peanut butter or honey,” she said. I didn’t like either, but I didn’t say so.

“Honey,” I said. She carried the mugs of tea, and I carried the plate of sandwiches. I followed her out across a cobbled courtyard, accompanied by the yappy dog, down some steps and into a great glass building where there stood a gigantic white horse. The floor was covered in newspaper, and everywhere was crunchy underfoot with plaster. The shelves all around were full of sculpted heads and arms and legs and hands. A white sculpture of a dog stood guard over the plate of sandwiches and never even sniffed them. She sipped her tea between her hands and looked up at the giant horse. The horse looked just like Peg, only a lot bigger.

“It’s no good,” she sighed. “She needs a rider.” She turned to me suddenly. “You wouldn’t be the rider, would you?” she asked.

“I can’t ride.”

“You wouldn’t have to, not really. You’d just sit there, that’s all, and I’d sketch you.”

“What, now?”

“Why not? After tea be all right?”

And so I found myself sitting astride Peg that same afternoon in the stable yard. She was tied up by her rope, pulling contentedly at her hay net and paying no attention to us whatsoever. It felt strange up there, with Peg shifting warm underneath me. There was no saddle, and she asked me to hold the reins one-handed, loosely, to feel “I was part of the horse”. The worst of it was that I was hot, stifling hot, because she had dressed me up as an Arab. I had great swathes of cloth over and around my head and I was draped to my feet with a long heavy robe so that nothing could be seen of my jeans or sweater or wellies.

“I never told you my name, did I?” said the lady, sketching furiously on a huge pad. “That was rude of me. I’m Liza. When you come tomorrow, you can give me a hand making you if you like. I’m not as strong as I was, and I’m in a hurry to get on with this. You can mix the plaster for me. Would you like that?” Peg snorted and pawed the ground. “I’ll take that as a yes, shall I?” She laughed, and walked round behind the horse, turning the page of her sketch pad. “I want to do one more from this side and one from the front, then you can go home.”

Half an hour later when she let me down and unwrapped me, my bottom was stiff and sore.

“Can I see?” I asked her.

“I’ll show you tomorrow,” she said. “You will come, won’t you?” She knew I would, and I did.

I came every day after that to muck out the stables and to walk Peg, but what I looked forward to most – even more than being with Peg – was mixing up Liza’s plaster for her in the bucket, climbing the stepladder with it, watching her lay the strips of cloth dunked in the wet plaster over the frame of the rider, building me up from the iron skeleton of wire, to what looked at first like an Egyptian mummy, then a riding Arab at one with his horse, his robes shrouding him with mystery. I knew all the while it was me in that skeleton, me inside that mummy. I was the Arab sitting astride his horse looking out over the desert. She worked ceaselessly, and with such a fierce determination that I didn’t like to interrupt. We were joined together by a common, comfortable silence.

At the end of a month or so we stood back, the two of us, and looked up at the horse and rider, finished.

“Well,” said Liza, her hands on her hips. “What do you think, Bonnie?”

“I wish,” I whispered, touching the tail of the horse, “I just wish I could do it.”

“But you did do it, Bonnie,” she said and I felt her hand on my shoulder. “We did it together. I couldn’t have done it without you.” She was a little breathless as she spoke. “Without you, that horse would never have had a rider. I’d never have thought of it. Without you mixing my plaster, holding the bucket, I couldn’t have done it.” Her hand gripped me tighter. “Do you want to do one of your own?”

“I can’t.”

“Of course you can. But you have to look around you first, not just glance, but really look. You have to breathe it in, become a part of it, feel that you’re a part of it. You draw what you see, what you feel. Then you make what you’ve drawn. Use clay if you like, or do what I do and build up plaster over a wire frame. Then set to work with your chisel, just like I do, until it’s how you want it. If I can do it, you can do it. I tell you what. You can have a corner of my studio if you like, just so long as you don’t talk when I’m working. How’s that?”

So my joyous spring blossomed into a wonderful summer. After a while, I even dared to ride Peg bareback sometimes on the way back to the stable yard; and I never forgot what Liza told me. I looked about me. I listened. And the more I listened and the more I looked, the more I felt at home in this new world. I became a creature of the place. I belonged there as much as the wren that sang at me high on the vegetable garden wall, as much as the green dragonfly hovering over the pool by the water buffalo. I sketched Peg. I sketched Big Boy (I couldn’t sketch Chip – he just came out round). I bent my wire frames into shape and I began to build my first horse sculpture, layer on layer of strips of cloth dunked in plaster just like Liza did. I moulded them into shape on the frame, and when they dried I chipped away and sanded. But I was never happy with what I’d done.

All this time, Liza worked on beside me in the studio, and harder, faster, more intensely than ever. I helped her whenever she asked me too, mixing, holding the bucket for her, just as I had done before.

It was a Rising Christ, she said, Christ rising from the dead, his face strong, yet gentle too, immortal it seemed; but his body, vulnerable and mortal. From time to time she’d come over and look at my stumpy effort that looked as much like a dog as a horse to me, and she would walk round it nodding her approval. “Coming on, coming on,” she’d say. “Maybe just a little bit off here perhaps.” And she’d chisel away for a minute or two, and a neck or leg would come to sudden life.

I told her once, “It’s like magic.”

She thought for a moment, and said, “That’s exactly what it is, Bonnie. It’s a God-given thing, a God-given magic, and it’s not to be wasted. Don’t waste it, Bonnie. Don’t ever waste it.”

The horse and rider came back from the foundry, bronze now and magnificent. I marvelled at it. It stood outside her studio, and when it caught the red of the evening sun, I could scarcely take my eyes off it. But these days Liza seemed to tire more easily, and she would sit longer over her tea, gazing out at her horse and rider.

“I am so pleased with that, Bonnie,” she said, “so pleased we did it together.”

The Christ figure was finished and went off to the foundry a few weeks before I had to go on my summer holiday. “By the time you come back again,” said Liza, “it should be back. It’s going to hang above the door of the village church. Isn’t that nice? It’ll be there for ever. Well, not for ever. Nothing is for ever.”

The holiday was in Cornwall. We stayed where we always did, in Cadgwith, and I drew every day. I drew boats and gulls and lobster pots. I made sculptures with wet sand – sleeping giants, turtles, whales – and everyone thought I was mad not to go swimming and boating. The sun shone for fourteen days. I never had such a perfect holiday, even though I didn’t have my bike, or Peg or Liza with me.

My first day back, the day before school began, I cycled out to Liza’s place with my best boat drawing in a stiff envelope under my sweater. The stable yard was deserted. There were no horses in the fields. Peg wasn’t in her stable and I could find no one up at the house, no Liza, no yappy dog. I stopped in the village to ask but there was no one about. It was like a ghost village. Then the church bell began to ring. I leant my bike up against the churchyard wall and ran up the path. There was Liza’s Rising Christ glowing in the sun above the doorway, and inside they were singing hymns.

I crept in, lifting the latch carefully so that I wouldn’t be noticed. The hymn was just finishing. Everyone was sitting down and coughing. I managed to squeeze myself in at the end of a pew and sat down too. The church was packed. A choir in red robes and white surplices sat on either side of the altar. The vicar was taking off his glasses and putting them away. I looked everywhere for Liza’s wild white curls, but could not find her. It was difficult for me to see much over everyone’s heads. Besides, some people were wearing hats, so I presumed she was too and stopped looking for her. She’d be there somewhere.

The vicar began. “Today was to be a great day, a happy day for all of us. Liza was to unveil her Rising Christ above the south door. It was her gift to us, to all of us who live here, and to everyone who will come here to our church in the centuries to come. Well, as we all now know, there was no unveiling, because she wasn’t here to do it. On Monday evening last she watched her Rising Christ winched into place. She died the next day.”

I didn’t hear anything else he said. It was only then that I saw the coffin resting on trestles between the pulpit and the lectern, with a single wreath of white flowers laid on it, only then that I took in the awful truth.

I didn’t cry as the coffin passed right by me on its way out of the church. I suppose I was still trying to believe it. I stood and listened to the last prayers over the grave, numb inside, grieving as I had never grieved before, or since, but still not crying. I waited until almost everyone had gone and went over to the grave. A man was taking off his jacket and hanging it on the branch of a tree. He spat on his hands, rubbed them and picked up his spade. He saw me. “You family?” he said.

“Sort of,” I replied. I reached inside my sweater and pulled out the boat drawing from Cadgwith. “Can you put it in?” I asked. “It’s a drawing. It’s for Liza.”

“Course,” he said, and he took it from me. “She’d like that. Fine lady, she was. The things she did with her hands. Magic, pure magic.”

It was just before Christmas the same year that a cardboard tube arrived in the post, addressed to me. I opened it in the secrecy of my room. A rolled letter fell out, typed and very short.

Dear Miss Mallet,

In her will, the late Liza Bonallack instructed us, her solicitors, to send you this drawing. We would ask you to keep us informed of any future changes of address.

With best wishes.

I unrolled it and spread it out. It was of me sitting on Peg, swathed in Arab clothes. Underneath was written:

For dearest Bonnie,

I never paid you for all that mucking out, did I? You shall have this instead, and when you are twenty-one you shall have the artist’s copy of our horse and rider sculpture. But by then you will be doing your own sculptures. I know you will.

God bless,

Liza.

So here I am, nearly thirty now. And as I look out at the settling snow from my studio, I see Liza’s horse and rider standing in my back garden, and all around, my own sculptures gathered in silent homage.

(#ulink_57f0533f-c090-5c59-90da-79db3df8a8f8)

was near by anyway, so I had every excuse to do it, to ignore the old adage and do something I’d been thinking of doing for many years. “Never go back. Never go back.” Those warning words kept repeating themselves in my head as I turned right at the crossroads outside Tillingham and began to walk the few miles along the road back to my childhood home in Bradwell, a place I’d last seen nearly fifty years before. I’d thought of it since, and often. I’d been there in my dreams, seen it so clearly in my mind, but of course I had always remembered it as it had been then. Fifty years would have changed things a great deal, I knew that. But that was part of the reason for my going back that day, to discover how intact was the landscape of my memories.

I wondered if any of the people I had known then might still be there; the three Stebbing sisters perhaps, who lived together in the big house with honeysuckle over the porch, very proper people so Mother always wanted me to be on my best behaviour. It was no more than a stone’s throw from the sea and there always seemed to be a gull perched on their chimney pot. I remembered how I’d fallen ignominiously into their goldfish pond and had to be dragged out and dried off by the stove in the kitchen with everyone looking askance at me, and my mother so ashamed. Would I meet Bennie, the village thug who had knocked me off my bike once because I stupidly wouldn’t let him have one of my precious lemon sherbets? Would he still be living there? Would we recognise one another if we met?

The whole silly confrontation came back to me as I walked. If I’d had the wit to surrender just one lemon sherbet he probably wouldn’t have pushed me, and I wouldn’t have fallen into a bramble hedge and had to sit there humiliated and helpless as he collected up my entire bagful of scattered lemon sherbets, shook them triumphantly in my face, and then swaggered off with his cronies, all of them scoffing at me, and scoffing my sweets too. I touched my cheek then as I remembered the huge thorn I had found sticking into it, the point protruding inside my mouth. I could almost feel it again with my tongue, taste the blood. A lot would never have happened if I’d handed over a lemon sherbet that day.

That was when I thought of Mrs Pettigrew and her railway carriage and her dogs and her donkey, and the whole extraordinary story came flooding back crisp and clear, every detail of it, from the moment she found me sitting in the ditch holding my bleeding face and crying my heart out.

She helped me up on to my feet. She would take me to her home. “It isn’t far,” she said. “I call it Dusit. It is a Thai word which means ‘halfway to heaven’.” She had been a nurse in Thailand, she said, a long time ago when she was younger. She’d soon have that nasty thorn out. She’d soon stop it hurting. And she did.

The more I walked the more vivid it all became: the people, the faces, the whole life of the place where I’d grown up. Everyone in Bradwell seemed to me to have had a very particular character and reputation, unsurprising in a small village, I suppose: Colonel Burton with his clipped moustache, who had a wife called Valerie, if I remembered right, with black pencilled eyebrows that gave her the look of someone permanently outraged – which she usually was. Neither the colonel nor his wife was to be argued with. They ruled the roost. They would shout at you if you dropped sweet papers in the village street or rode your bike on the pavement.

Mrs Parsons, whose voice chimed like the bell in her shop when you opened the door, liked to talk a lot. She was a gossip, Mother said, but she was always very kind. She would often drop an extra lemon sherbet into your paper bag after she had poured your quarter pound from the big glass jar on the counter. I had once thought of stealing that jar, of snatching it and running off out of the shop, making my getaway like a bank robber in the films. But I knew the police would come after me in their shiny black cars with their bells ringing, and then I’d have to go to prison and Mother would be cross. So I never did steal Mrs Parsons’s lemon sherbet jar.

Then there was Mad Jack, as we called him, who clipped hedges and dug ditches and swept the village street. We’d often see him sitting on the churchyard wall by the mounting block eating his lunch. He’d be humming and swinging his legs. Mother said he’d been fine before he went off to the war, but he’d come back with some shrapnel from a shell in his head and never been right since, and we shouldn’t call him Mad Jack, but we did. I’m ashamed to say we baited him sometimes too, perching alongside him on the wall, mimicking his humming and swinging our legs in time with his.

But Mrs Pettigrew remained a mystery to everyone. This was partly because she lived some distance from the village and was inclined to keep herself to herself. She only came into the village to go to church on Sundays, and then she’d sit at the back, always on her own. I used to sing in the church choir, mostly because Mother made me, but I did like dressing up in the black cassock and white surplice and we did have a choir outing once a year to the cinema in Southminster – that’s where I first saw Snow White and Bambi and Reach for the Sky. I liked swinging the incense too, and sometimes I got to carry the cross, which made me feel very holy and very important. I’d caught Mrs Pettigrew’s eye once or twice as we processed by, but I’d always looked away. I’d never spoken to her. She smiled at people, but she rarely spoke to anyone; so no one spoke to her – not that I ever saw anyway. But there were reasons for this.

Mrs Pettigrew was different. For a start she didn’t live in a house at all. She lived in a railway carriage, down by the sea wall with the great wide marsh all around her. Everyone called it Mrs Pettigrew’s Marsh. I could see it best when I rode my bicycle along the sea wall. The railway carriage was painted brown and cream and the word PULLMAN was printed in big letters all along both sides above the windows. There were wooden steps up to the front door at one end, and a chimney at the other. The carriage was surrounded by trees and gardens, so I could only catch occasional glimpses of her and her dogs and her donkey, bees and hens. Tiny under her wide hat, she could often be seen planting out in her vegetable garden, or digging the dyke that ran around the garden like a moat, collecting honey from her beehives perhaps or feeding her hens. She was always outside somewhere, always busy. She walked or stood or sat very upright, I noticed, very neatly, and there was a serenity about her that made her unlike anyone else, and ageless too.

But she was different in another way. Mrs Pettigrew was not like the rest of us to look at, because Mrs Pettigrew was “foreign”, from somewhere near China, I had been told. She did not dress like anyone else either. Apart from the wide-brimmed hat, she always wore a long black dress buttoned to the neck. And everything about her, her face and her hands, her feet, everything was tidy and tiny and trim, even her voice. She spoke softly to me as she helped me to my feet that day, every word precisely articulated. She had no noticeable accent at all, but spoke English far too well, too meticulously, to have come from England.

So we walked side by side, her arm round me, a soothing silence between us, until we turned off the road on to the track that led across the marsh towards the sea wall in the distance. I could see smoke rising straight into the sky from the chimney of the railway carriage.

“There we are: Dusit,” she said. “And look who is coming out to greet us.”

Three greyhounds were bounding towards us followed by a donkey trotting purposefully but slowly behind them, wheezing at us rather than braying. Then they were gambolling all about us, and nudging us for attention. They were big and bustling, but I wasn’t afraid because they had nothing in their eyes but welcome.

“I call the dogs Fast, Faster and Fastest,” she told me. “But the donkey doesn’t like names. She thinks names are for silly creatures like people and dogs who can’t recognise one another without them. So I call her simply Donkey.” Mrs Pettigrew lowered her voice to a whisper. “She can’t bray properly – tries all the time but she can’t. She’s very sensitive too; takes offence very easily.” Mrs Pettigrew took me up the steps into her railway carriage home. “Sit down there by the window, in the light, so I can make your face better.”

I was so distracted and absorbed by all I saw about me that I felt no pain as she cleaned my face, not even when she pulled out the thorn. She held it out to show me. It was truly a monster of a thorn. “The biggest and nastiest I have ever seen,” she said, smiling at me. Without her hat on she was scarcely taller than I was. She made me wash out my mouth and bathed the hole in my cheek with antiseptic. Then she gave me some tea which tasted very strange but warmed me to the roots of my hair. “Jasmine tea,” she said. “It is very healing, I find, very comforting. My sister sends it to me from Thailand.”

The carriage was as neat and tidy as she was: a simple sitting room at the far end with just a couple of wicker chairs and a small table by the stove. And behind a half-drawn curtain I glimpsed a bed very low on the ground. There was no clutter, no pictures, no hangings, only a shelf of books that ran all the way round the carriage from end to end. From where I was sitting I could see out over the garden, then through the trees to the open marsh beyond.

“Do you like my house, Michael?” She did not give me time to reply. “I read many books, as you see,” she said. I was wondering how it was that she knew my name, when she told me. “I see you in the village sometimes, don’t I? You’re in the choir, aren’t you?” She leant forward. “And I expect you’re wondering why Mrs Pettigrew lives in a railway carriage.”

“Yes,” I said.

The dogs had come in by now and were settling down at our feet, their eyes never leaving her, not for a moment, as if they were waiting for an old story they knew and loved.

“Then I’ll tell you, shall I?” she began. “It was because we met on a train, Arthur and I – not this one, you understand, but one very much like it. We were in Thailand. I was returning from my grandmother’s house to the city where I lived. Arthur was a botanist. He was travelling through Thailand collecting plants and studying them. He painted them and wrote books about them. He wrote three books; I have them all up there on my shelf. I will show you one day – would you like that? I never knew about plants until I met him, nor insects, nor all the wild creatures and birds around us, nor the stars in the sky. Arthur showed me all these things. He opened my eyes. For me it was all so exciting and new. He had such a knowledge of this wonderful world we live in, such a love for it too. He gave me that, and he gave me much more: he gave me his love too.

“Soon after we were married he brought me here to England on a great ship – this ship had three big funnels and a dance band – and he made me so happy. He said to me one day on board that ship, ‘Mrs Pettigrew –’ he always liked to call me this – ‘Mrs Pettigrew, I want to live with you down on the marsh where I grew up as a boy.’ The marsh was part of his father’s farm, you see. ‘It is a wild and wonderful place,’ he told me, ‘where on calm days you can hear the sea breathing gently beyond the sea wall, or on stormy days roaring like a dragon, where larks rise and sing on warm summer afternoons, where stars cascade on August nights.’

“‘But where shall we live?’ I asked him.

“‘I have already thought of that, Mrs Pettigrew,’ he said. ‘Because we first met on a train, I shall buy a fine railway carriage for us to live in, a carriage fit for a princess. And all around it we shall make a perfect paradise and we shall live as we were meant to live, amongst our fellow creatures, as close to them as we can be. And we shall be happy there.’

“‘So we were, Michael. So we were. But only for seventeen short months, until one day there was an accident. We had a generator to make our electricity; Arthur was repairing it when the accident happened. He was very young. That was nearly twenty years ago now. I have been here ever since and I shall always be here. It is just as Arthur told me: a perfect paradise.”

Donkey came in just then, clomping up the steps into the railway carriage, her ears going this way and that. She must have felt she was being ignored or ostracised, probably both. Mrs Pettigrew shooed her out, but not before there was a terrific kerfuffle of wheezing and growling, of tumbling chairs and crashing crockery.

When I got home I told Mother everything that had happened. She took me to the doctor at once for a tetanus injection, which hurt much more than the thorn had, then put me to bed and went out – to sort out Bennie, she said. I told her not to, told her it would only make things worse. But she wouldn’t listen. When she came back she brought me a bag of lemon sherbets. Bennie, she told me, had been marched down to Mrs Parsons’s shop by his father and my mother, and they had made him buy me a bag of lemon sherbets with his own pocket money to replace the ones he’d pinched off me.

Mother had also cycled out to see Mrs Pettigrew to thank her. From that day on the two of them became the best of friends, which was wonderful for me because I was allowed to go cycling out to see Mrs Pettigrew as often as I liked. Sometimes Mother came with me, but mostly I went alone. I preferred it on my own.

I rode Donkey all over the marsh. She needed no halter, no reins. She went where she wanted and I went with her, followed always by Fast, Faster and Fastest, who would chase rabbits and hares wherever they found them. I was always muddled as to which dog was which, because they all ran unbelievably fast – standing start to full throttle in a few seconds. They rarely caught anything, but they loved the chase.

With Mrs Pettigrew I learnt how to puff the bees to sleep before taking out the honeycomb. I collected eggs warm from the hens, dug up potatoes, pulled carrots, bottled plums and damsons in Kilner jars. (Ever since, whenever I see the blush on a plum I always think of Mrs Pettigrew.) And always Mrs Pettigrew would send me home afterwards with a present for Mother and me, a pot of honey perhaps or some sweetcorn from her garden.

Sometimes Mrs Pettigrew would take me along the sea wall all the way to St Peter’s Chapel and back, the oldest chapel in England, she said. Once we stopped to watch a lark rising and rising, singing and singing so high in the blue we could see it no more. But the singing went on, and she said, “I remember a time – we were standing almost on this very same spot – when Arthur and I heard a lark singing just like that. I have never forgotten his words. ‘I think it’s singing for you,’ he said, ‘singing for Mrs Pettigrew.’”

Then there was the night in August when Mother and Mrs Pettigrew and I lay out on the grass in the garden gazing up at the shooting stars cascading across the sky above us, just as she had with Arthur, she said. How I wondered at the glory of it, and the sheer immensity of the universe. I was so glad then that Bennie had pushed me off my bike that day, so glad I had met Mrs Pettigrew, so glad I was alive. But soon after came the rumours and the meetings and the anger, and all the gladness was suddenly gone.

I don’t remember how I heard about it first. It could have been in the playground at school, or Mother might have told me or even Mrs Pettigrew. It could have been Mrs Parsons in the shop. It doesn’t matter. One way or another, everyone in the village and for miles around got to hear about it. Soon it was all anyone talked about. I didn’t really understand what it meant to start with. It was that first meeting in the village hall that brought it home to me. There were pictures and plans of a giant building pinned up on the wall for everyone to see. There was a model of it too, with the marsh all around and the sea wall running along behind it, and the blue sea beyond with models of fishing boats and yachts sailing by. That, I think, was when I truly began to comprehend the implication of what was going on, of what was actually being proposed. The men in suits sitting behind the table on the platform that evening made it quite clear.