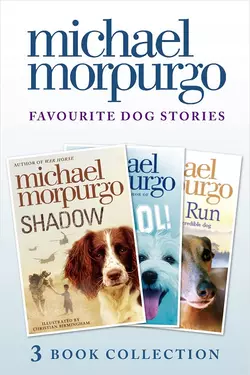

Favourite Dog Stories: Shadow, Cool! and Born to Run

Michael Morpurgo

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Природа и животные

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 288.34 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Tales from the nation’s favourite storyteller about man’s best friend who will do anything to protect their loving owners.‘Shadow’:Aman and his mother live in war-torn Afghanistan. When a Western dog appears at the mouth of their cave, it soon becomes Aman’s constant companion, his shadow as he calls her. But life is becoming increasingly dangerous for Aman and his family…‘Cool!’:Michael Morpurgo’s inspiring new story of Robbie, a boy in a coma – victim of a car accident. Locked inside his own head, able to hear but not move or speak, Robbie tries to keep himself from slipping ever deeper into unconsciousness.‘Born to Run’:When Patrick saves a litter of greyhound puppies from the canal, he can’t bear to hand them all over to the RSPCA. He pleads with his parents: couldn’t he just keep one of them? Patrick christens his puppy Best Mate, and that’s what he becomes. Until one day Best Mate is kidnapped by a greyhound trainer, and begins a new life as a champion race dog. Suzie, the greyhound trainer’s step-daughter, loves Best Mate on first sight and gives him a new name, Bright Eyes. But what will happen when he can’t run any more?