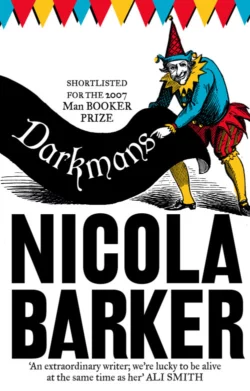

Darkmans

Nicola Barker

This is a rowdy, riotous tale, a tale in which the medieval past takes on a face, name, and occupation and roams around the humdrum town of Ashford, bringing chaos to the lives of those it picks on. No one is safe: not upstanding Beede and his drug-dealing son, nor teen chav Kelly who zestily finds God (much to the dismay of the Reverend responsible), or Gaffar, the tiny, amorous Kurd with an unusual fear of salad.Darkmans is a world where language snaps and crackles like static, twitching with barely containable energy. Past and present mingle and blur, and the lines between fantasy and reality, sanity and madness are continually rubbed out and redrawn - but by whose hand? And what about the grand scheme of things - is life a coincidence or is it a pattern, plotted by all-seeing, unknown forces?The third of Nicola Barker's visionary narratives of the Thames Gateway, Darkmans is a very modern book about very old-fashioned subjects: love and jealousy. It's also about invasion, obsession, displacement and possession, about comedy, art, prescription drugs and chiropody. Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize 2007 and following on from Wide Open (winner Dublin IMPAC award 2000) and Behindlings it confirms Nicola Barker as one of Britain's most original, innovative and exciting literary talents.

NICOLA BARKER

Darkmans

Dedication (#ulink_d69d7b12-8eab-5c90-b88d-25a31cefd20b)

For Scott Ehrig-Burgess in Del Mar, who filled out that comment card

Epigraph (#ulink_081dee3c-547c-5a37-81ce-4007f0b0cccb)

‘These demanders for glimmer be for the most part women;

for glimmer, in their language, is fire.’

Thomas Harman – A Caveat for Common Cursitors 1567

Contents

Cover (#u56808340-c1da-5091-814e-9845ed4c0d1f)

Title page (#ud50be84c-a106-5653-9374-394a0cfb90bf)

Dedication (#u6cb8ec7c-6019-5beb-b33b-70002e470155)

Epigraph (#u2aae7b98-4194-5b46-910f-bf211e62949b)

PART ONE (#u14f504f2-5662-5ecb-a6cd-1ed5465156f0)

ONE (#uf7fce8ba-3afa-59e0-8ca6-ba2a3d329893)

TWO (#uc48573af-5805-54f5-b6c4-0a76d7bb9b99)

THREE (#uc85d7498-08fc-5d7f-8e72-732b547e7eb8)

FOUR (#u9765fe54-5752-51d7-8817-32a79880398a)

FIVE (#u299e22fa-47c1-5abd-9345-67ab1390ec2a)

SIX (#ue9487bc6-3c52-5361-90d1-0e144241ff44)

SEVEN (#u7f7db67b-caaf-57b0-9679-8c1c850d76af)

EIGHT (#uf36a5ba0-2e1b-50f8-ab76-e747720b9769)

PART TWO (#ubb07f9fc-1b49-51db-9b20-fda042217bd3)

FLEET (#udcdf25da-6097-5936-89b1-0d90b0d92351)

ELEN (#u67cc40bb-d669-579b-8ba4-d7f1f245d20c)

ABACUS BUILDERS LTD (#u4e710b68-5c5c-5378-ab3d-4c992f42a753)

ISIDORE (#u563dddb1-a9a4-520d-bc18-4f4d5cbc5509)

PART THREE (#ua063c0e7-15bb-510f-9335-b1f2ece467d5)

ONE (#u21ca04ce-9244-56a6-862f-a3ed1e7cc67b)

TWO (#u898107f9-050b-5344-8260-fcf3a3c68b0d)

THREE (#u2270d798-513a-5035-b3c7-f2896cd71ef8)

FOUR (#u17855205-cbe4-52ec-8df7-a646bc91dcda)

FIVE (#uc9d75fb3-2b4d-5780-982a-e7bfd85b5a5b)

SIX (#u0bae999f-92a0-54ae-af99-1e324932e147)

SEVEN (#u5011ec10-0065-5c2d-8f9d-3e9e280956fd)

EIGHT (#ub0af97bc-bd89-50c8-9e35-5e9399bd14fe)

NINE (#u7bcf58a7-c711-59fe-9019-537b9118a1dd)

TEN (#u43e8b0c5-8023-5ad5-a4bf-08fc61a8fa52)

ELEVEN (#u8a314643-2148-5f75-9ff4-e66a68698ac0)

PART FOUR (#u2c4a8821-a52a-5969-952a-fa674bee047c)

DUNGENESS (#ufc4e60d5-57dd-51db-8d0f-ad7a0488be7a)

JURY’S GAP (#uf25e92e6-2f00-50e2-a53c-dd39bd2e1f4e)

WINCHELSEA (#u5dd794f7-a7cd-5575-af31-505fc7ffeed9)

BECKLEY, NO, NO…BIXLEY WOODS (#uc5e10bd6-ba9e-5adc-8097-d13abf9054d8)

PART FIVE (#u629e849d-6874-5935-bcd8-d7e0b80cf6f7)

ONE (#u81cd182e-c6f3-59dc-8cc1-bfa163754ec4)

TWO (#u2de58831-89a0-54da-b37a-5a4cc736fcdb)

THREE (#u81131b4f-02a6-55cc-905e-8b1c1f3ba753)

FOUR (#uafe619c3-7a29-544e-a9a0-57a0b89b3bcd)

FIVE (#u258c8bc4-cd33-5614-9053-9cf17a8f7ff7)

SIX (#u63bc7982-02f6-5e8c-aced-c80ac228c2cb)

SEVEN (#u55aa3a1f-42d6-553a-b9aa-966b251b8c73)

EIGHT (#u16b4d46f-d0b7-5743-947d-55e7a17bdfb0)

NINE (#u6ca2c6c1-9c96-5089-aede-fbb15ed7f4f7)

TEN (#u543c8ec8-58b8-519d-8851-a69d2e5837a1)

ELEVEN (#u2c72a529-1a7d-5f5f-a2f6-9ef577115a03)

TWELVE (#uab672fd9-08a8-505f-b3af-ebbe7f166155)

THIRTEEN (#ub1646515-ff95-5956-9036-b60c39d83c3b)

FOURTEEN (#ue64a2020-3660-5863-94f1-73a23af7c2f8)

FIFTEEN (#uea7ff14c-0bb5-5955-907f-dd977a12e65d)

SIXTEEN (#uc550ff14-b0c6-5c69-a2f5-e5470fc731d4)

SEVENTEEN (#u84507691-6ec7-54aa-9bd0-da43affad607)

EIGHTEEN (#u9a033e01-6021-521d-a3af-9bf40faada01)

NINETEEN (#ubbf7c8fe-3baf-5199-a428-a4b4f94708dd)

TWENTY (#u20a9876b-5781-541d-acdd-bfcf904c8b7f)

Also by Nicola Barker (#u2d9786fb-c9d4-52ab-899b-4611a125ba64)

Praise (#u5e98db22-7ea9-5cbb-9d22-9f67e53d2de9)

Copyright (#uc8ce38bd-4c41-59d7-9739-59623f8b6aa6)

About the publisher (#u60ae4e23-76f2-5d9b-a982-889a0648fba4)

PART ONE (#ulink_699a5e38-cc88-577e-a575-024c554fe56d)

ONE (#ulink_4d181b92-e70d-5b97-9a5f-5fd049ebc2f6)

Kane dealt prescription drugs in Ashford; the Gateway to Europe. His main supplier was Anthony Shilling, a Waste Management Coordinator at the Frances Fairfax. Shilling was a quiet, Jamaican gentleman (caucasian – his family originally plantation owners) who came to England in the early seventies, settled in Dalston, London, and fell in love with a woman called Mercy, whose own family hailed from The Dominican Republic.

Mercy was British born. Anthony and Mercy moved to South Kent in 1976, where they settled and raised four daughters, one of whom was a professor of Political Sciences at Leeds University and had written a book called Culture Clashes: Protest Songs and The Yardies (1977–1999).

Kane was waiting for Anthony at the French Connection; a vulgar, graceless, licensed ‘family restaurant’ (a mammoth, prefabricated hut, inside of which a broad American roadhouse mentality rubbed up against all that was most intimate and accessible in Swiss chalet-style decor) on the fringes of the Orbital Park, one of Ashford’s three largest – and most recent – greenfield industrial development sites.

The restaurant had been thoughtfully constructed to service the adjacent Travel Inn, which had, in turn, been thoughtfully constructed to service the through-traffic from the Channel Tunnel, much of which still roared carelessly past, just beyond the car park, the giant, plastic, fort-themed children’s play area, the slight man-made bank and the formless, aimless tufts of old meadow and marshland with which the Bad Munstereifel Road (named after Ashford’s delightful, medieval German twin) was neatly – if inconclusively – hemmed.

It was still too early for lunch on a Tuesday morning, and Kane (who hadn’t been to bed yet) was slouched back in a heavily varnished pine chair, sucking ruminatively on a fresh Marlboro, and staring quizzically across the table at Beede, his father.

Beede also worked at the Frances Fairfax, where he ran the laundry with an almost mythical efficiency. Beede was his surname. His first name – his Christian name – was actually Daniel. But people knew him as Beede and it suited him well because he was small, and hard, and unquestionably venerable (in precisely the manner of his legendarily bookish eighth-century precursor).

Beede knew all about Kane’s business dealings, and didn’t actually seem to give a damn that his only son was cheerfully participating in acts of both a legally and ethically questionable nature. Yet Anthony Shilling’s involvement was – in Beede’s opinion – an altogether different matter. He just couldn’t understand it. It deeply perplexed him. He had liked and admired both Tony and Mercy for many years. He considered them ‘rounded’; a respectable, comfortable, functional couple. Mercy had been a friend of Kane’s mother, Heather (now deceased – she and Beede had separated when Kane was still a toddler). Beede struggled to comprehend Tony’s motivation. He knew that it wasn’t just a question of money. But that was all he knew, and he didn’t dare (or care) to enquire any further.

‘Beede.’ Kane suddenly spoke. Beede glanced up from his second-hand Penguin orange-spine with a quick frown. Kane took a long drag on his cigarette.

‘Well?’

Beede was irritable.

Kane exhaled at his leisure.

‘What the fuck are you doing?’

Kane’s tone was not aggressive, more lackadaisical, and leavened by its trademark tinge of gentle mockery.

Beede continued to scowl. ‘What does it look like?’

He shook the book at Kane – by way of an answer – then returned to it, huffily.

Kane wasn’t in the slightest bit dismayed by the sharpness of Beede’s response.

‘But why the fuck,’ he said, ‘are you doing it here?’

Beede didn’t even look up this time, just indicated, boredly, towards his coffee cup. ‘Should I draw you a picture?’

Kane smiled.

He and Beede were not close. And they were not similar, either. They were different in almost every conceivable way. Beede was lithe, dark, strong-jawed, slate-haired and heavily bespectacled. He seemed like the kind of man who could deal with almost any kind of physical or intellectual challenge –

It’s the radiator. If you want to try and limp back home with it, I’ll need a tub of margarine, a litre of water and a packet of Stimorol; but I won’t make you any promises…

Ned Kelly’s last ever words? Spoken as he stood on the scaffold: ‘Such is life.’

You’re saying you’ve never used a traditional loom before? Well it’s pretty straightforward…

Yes, I do believe the earwig is the only insect which actually suckles its young.

No. Nietzsche didn’t hate humanity. That’s far too simplistic. What Nietzsche actually said was, ‘Man is something which must be overcome.’

To all intents and purposes Daniel Beede was a model citizen. So much so, in fact, that in 1983 he’d been awarded the Freedom of the Borough as a direct consequence of his tireless work in charitable and community projects during the previous two decades.

He was Ashford born and bred; a true denizen of a town which had always – but especially in recent years – been a landmark in social and physical re-invention. Ashford was a through-town, an ancient turnpike (to Maidstone, to Hythe, to Faversham, to Romney, to Canterbury), a geographical plughole; a place of passing and fording (Ash-ford, formerly Essetesford, the Eshe being a tributary of the River Stour).

Yet in recent years Beede had been in the unenviable position of finding his own home increasingly unrecognisable to him (Change; My God! He woke up, deep in the night, and could no longer locate himself. Even the blankets felt different – the quality of light through his window – the air). Worse still, Beede currently considered himself to be one of the few individuals in this now flourishing ‘Borough of Opportunity’ (current population c. 102,000) to have been washed up and spat out by the recent boom.

Prior to his time (why not call it a Life Sentence?) in the hospital laundry, Beede had worked – initially at ground level (exploiting his naval training), then later, in a much loftier capacity – for Sealink (the ferry people), and had subsequently become a significant figure at Mid-Kent Water plc; suppliers of over 36 million gallons of H2O, daily, to an area of almost 800 square miles.

If you wanted to get specific about it (and Beede always got specific) his life and his career had been irreparably blighted by the arrival of the Channel Tunnel; more specifically, by the eleventh-hour re-routing of the new Folkestone Terminal’s access road from the north to the south of the tiny, nondescript Kentish village of Newington (where Beede’s maternal grandmother had once lived) in 1986.

Rather surprisingly, the Chunnel hadn’t initially been Beede’s political bête noire. He’d always been studiously phlegmatic about its imminence. The prospect of its arrival had informed (and seasoned) his own childhood in much the same way that it had informed both his parents’ and his grandparents’ before them (as early as the brief Peace of Amiens, Napoleon was approached by Albert Mathieu Favier – a mining engineer from Northern France – who planned to dig out two paved and vaulted passages between Folkestone and Cap Gris-Nez; the first, a road tunnel, lit by oil lamps and ventilated by iron chimneys, the second, to run underneath it, for drainage. This was way back in 1802. The subsequent story of the tunnel had been a long and emotionally exhausting tale spanning two centuries and several generations; an epic narrative with countless dead-ends, low-points, disasters and casualties. Daniel Beede – and he was more than happy to admit as much – was merely one of these).

Politically, ideologically, Beede had generally been of a moderate bent, but at heart he was still basically progressive. And he’d always believed in the philosophy of ‘a little and often’, which – by and large – had worked well for him.

Yes, of course – on the environmental brief – he’d been passingly concerned about the loss of the rare Spider Orchid (the site of the proposed Folkestone Terminal was one of the few places it flourished, nationally), and not forgetting the currently endangered great crested newt, which Beede remembered catching as a boy in local cuts and streams with his simple but robust combination of a small mesh net and marmalade-jar.

And yes, he was well aware – more, perhaps, than anybody – of what the true (and potentially devastating) implications of a Channel link would be on the Kentish shipping industry (a loss of around 20,000 jobs was, at that time, the popular estimate).

And yes, yes, he had even harboured serious fears – and quite correctly, as it later transpired – that many of the employment opportunities on the project would pass over local people (at that point Ashford had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country) to benefit non-indigens, outside investors and foreign businesses.

It went without saying that the Chunnel (now a source of such unalloyed national complacency and pride) had caused huge headaches – and terrible heartache – in East Kent, but Beede’s greatest betrayal had been on a much smaller, more informal, more abstract level.

Beede’s maternal grandmother’s home had been a neat, quaint, unpretentious little cottage (pottery sink, tile floors, outside lavvy) in the middle of a symmetrical facade of five known as Church Cottages. They were located at the conjunction of the old School Road and Newington’s main, central thoroughfare The Street (no shop, no pub, twenty-five houses, at a push).

Much as their name implies, Church Cottages enjoyed a close physical proximity with Newington’s twelfth-century church and its similarly ancient – and much-feted – graveyard Yew.

Beede’s paternal grandparents (to whom he was slightly less close) also lived locally – several hundred yards north up the aforementioned Street – in the neighbouring village of Peene. Just so long as any inhabitant of either of these two tiny Kentish villages could remember, they had considered themselves a single community.

When the developer’s plans for the new Folkestone Terminal were initially proposed, however, it quickly became apparent that all this was soon about to change. Several farms and properties (not least, the many charming, if ramshackle homes in the idiosyncratic Kentish hamlet of Danton Pinch) were to be sacrificed to the terminal approach and concourse, not to mention over 500 acres of prime farmland and woodland, as well as all remaining evidence of the old Elham Valley Railway (built in 1884, disused since 1947). But worse still, the access road from the terminal to the M20 was due to cut a wide path straight between Newington and Peene, thereby cruelly separating them, forever.

Beede’s maternal grandmother and paternal grandparents were now long gone. Beede’s mother had died of breast cancer in 1982. His part-senile father now lived with Beede’s older brother on the south coast, just outside Hastings.

Beede’s parents had moved to the heart of Ashford (14 miles away) two years before he was even conceived, but Beede maintained a lively interest in their old stamping ground; still visited it regularly, had many contacts among the local Rotary and Cricket Clubs (the cricket grounds were yet another Chunnel casualty), friends and relatives in both of the affected villages, and a strong sense – however fallacious – that the union of these two places (like the union of his two parents) was a critical – almost a physical – part of his own identity.

They could not be divided.

It was early in the spring of 1984 when he first became aware of Eurotunnel’s plans. Beede was a well-seasoned campaigner and local prime mover. His involvement was significant. His opinions mattered. And he was by no means the only dynamic party with a keen interest in this affair. There were countless others who felt equally strongly, not least (it soon transpired) Shepway’s District Council. On closer inspection of the proposed scheme, the Council had become alarmed by the idea that this divisive ‘Northern Access Route’ might actively discourage disembarking Chunnel traffic from travelling to Dover, Folkestone or Hythe (Shepway’s business heartland) by feeding it straight on to the M20 (and subsequently straight on to London). The ramifications of this decision were perceived as being potentially catastrophic for local businesses and the tourist trade.

A complaint was duly lodged. The relevant government committee (where the buck ultimately stopped) weighed up the various options on offer and then quietly turned a blind eye to them. But the fight was by no means over. In response, the Council, Beede, and many residents of Newington and Peene got together and threatened a concerted policy of non-cooperation with Eurotunnel if a newly posited scheme known as ‘The Shepway Alternative’ (a scheme still very much in its infancy) wasn’t to be considered as a serious contender.

In the face of such widespread opposition the committee reassessed the facts and – in a glorious blaze of publicity – backed down. The decision was overturned, and the new Southern Access Route became a reality.

This small but hard-won victory might’ve been an end to the Newington story. But it wasn’t. Because now (it suddenly transpired) there were to be other casualties, directly as a consequence of this hard-won Alternative. And they would be rather more severe and destructive than had been initially apprehended.

To keep their villages unified, Newington and Peene had sacrificed a clutch of beautiful, ancient properties (hitherto unaffected by the terminal scheme) which stood directly in the path of the newly proposed Southern Link with the A20 and the terminal. One of these was the grand Victorian vicarage, known as The Grange, with its adjacent Coach House (now an independent dwelling). Another, the magnificent, mid-sixteenth-century farmhouse known as Stone Farm. Yet another, the historic water mill (now non-functioning, but recently renovated and lovingly inhabited, with its own stable block) known as Mill House.

Beede wasn’t naive. He knew only too well how the end of one drama could sometimes feed directly into the start of another. And so it was with the advent of what soon became known as ‘The Newington Hit List’.

Oh the uproar! The sense of local betrayal! The media posturing and ranting! The archaeological chaos engendered by this eleventh-hour re-routing! And Beede (who hadn’t, quite frankly, really considered all of these lesser implications – Mid-Kent Water plc didn’t run itself, after all) found himself involved (didn’t he owe the condemned properties that much, at least?) in a crazy miasma of high-level negotiations, conservation plans, archaeological investigations and restoration schemes, in a last-ditch attempt to rectify the environmental devastation which (let’s face it) he himself had partially engendered.

Eurotunnel had promised to dismantle and re-erect any property (or part of a property) that was considered to be of real historical significance. The Old Grange and its Coach House were not ‘historical’ enough for inclusion in this scheme and were duly bulldozered. Thankfully some of the other properties did meet Eurotunnel’s high specifications. Beede’s particular involvement was with Mill House, which – it soon transpired – had been mentioned in the Domesday Book and had a precious, eighteenth-century timber frame.

The time for talking was over. Beede put his money where his mouth was. He shut up and pulled on his overalls. And it was hard graft: dirty, heavy, time-consuming work (every tile numbered and categorised, every brick, every beam), but this didn’t weaken Beede’s resolve (Beede’s resolve was legendary. He gave definition to the phrase ‘a stickler’).

Beede was committed. And he was not a quitter. Early mornings, evenings, weekends, he toiled tirelessly alongside a group of other volunteers (many of them from Canterbury’s Archaeological Trust) slowly, painstakingly, stripping away the mill’s modern exterior, and (like a deathly coven of master pathologists), uncovering its ancient skeleton below.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. At some point (and who could remember when, exactly?) it became distressingly apparent that recent ‘improvements’ to the newer parts of Mill House had seriously endangered the older structure’s integrity –

Now hang on –

Just…just back up a second –

What are you saying here, exactly?

The worst-case scenario? That the old mill might never be able to function independently in its eighteenth-century guise; like a conjoined twin, it might only really be able to exist as a small part of its former whole.

But the life support on the newer part had already been switched off (they’d turned it off themselves, hadn’t they? And with such care, such tenderness), so gradually – as the weeks passed, the months – the team found themselves in the unenviable position of standing helplessly by and watching – with a mounting sense of desolation – as the older part’s heartbeat grew steadily weaker and weaker. Until one day, finally, it just stopped.

They had all worked so hard, and with such pride and enthusiasm. But for what? An exhausted Beede staggered back from the dirt and the rubble (a little later than the others, perhaps; his legendary resolve still inappropriately firm), shaking his head, barely comprehending, wiping a red-dust-engrained hand across a moist, over-exerted face. Marking himself. But there was no point in his war-painting. He was alone. The fight was over. It was lost.

And the worst part? He now knew the internal mechanisms of that old mill as well as he knew the undulations of his own ribcage. He had crushed his face into its dirty crevices. He had filled his nails with its sawdust. He had pushed his ear up against the past and had sensed the ancient breath held within it. He had gripped the liver of history and had felt it squelching in his hand –

Expanding –

Struggling –

So what now? What now? What to tell the others? How to make sense of it all? How to rationalise? Worse still, how to face the hordes of encroaching construction workers in their bright yellow TML uniforms, with their big schemes and tons of concrete, with their impatient cranes and their diggers?

Beede had given plenty in his forty-odd years. But now (he pinched himself. Shit. He felt nothing) he had given too much. He had found his limit. He had reached it and he had over-stepped it. He was engulfed by disappointment. Slam-dunked by it. He could hardly breathe, he felt it so strongly. His whole body ached with the pain of it. He was so stressed – felt so invested in his thwarted physicality – that he actually thought he might be developing some kind of fatal disease. Pieces of him stopped functioning. He was broken.

And then, just when things seemed like they couldn’t get any worse –

Oh God!

The day the bulldozers came…

(He’d skipped work. They’d tried to keep him off-site. There was an ugly scuffle. But he saw it! He stood and watched – three men struggling to restrain him – he stood and he watched – jaw slack, mouth wide, gasping – as History was unceremoniously gutted and then steam-rollered. He saw History die –

NO!

You’re killing History!

STOP!)

– just when things seemed like they were hitting rock bottom (‘You need a holiday. A good rest. You’re absolutely exhausted – dangerously exhausted; mentally, physically…’) things took one further, inexorable, downward spiral.

The salvageable parts of the mill had been taken into storage by Eurotunnel. One of the most valuable parts being its ancient Kent Peg Tiles –

Ah yes

Those beautiful tiles…

Then one day they simply disappeared.

They had been preserved. They had been maintained. They had been entrusted. They had been lost.

BUT WHERE THE HELL ARE THEY?

WHERE DID THEY GO?

WHERE?

WHERE?!

It had all been in vain. And nobody really cared (it later transpired, or if they did, they stopped caring, eventually – they had to, to survive it), except for Beede – who hadn’t really cared that much in the first place – but who had done something bold, something decisive, something out of the ordinary; Beede – who had committed himself, had become embroiled, then engrossed, then utterly preoccupied, then thoroughly –

Irredeemably

– fucked up and casually (like the past itself) discarded.

And no, in the great scheme of things, it didn’t amount to very much. Just some old beams, some rotten masonry, some traditional tiles. But Beede suddenly found that he’d lost not only those tiles, but his own rudimentary supports. His faith. The roof of Beede’s confidence had been lifted and had blown clean away. His optimism. He had lost it. It just went.

And nothing – nothing – had felt the same, afterwards. Nothing had felt comfortable. Nothing fitted. A full fifteen years had passed, and yet – and at complete variance with the cliché – for Beede time had been anything but a great healer.

Progress, modernity (all now dirty words in Beede’s vocabulary) had kicked him squarely in the balls. I mean he hadn’t asked for much, had he? He’d sacrificed the Spider Orchid, hadn’t he? A familiar geography? He’d only wanted, out of respect, to salvage…to salvage…

What?

A semblance of what had been? Or was it just a question of…was it just a matter of…of form? Something as silly and apparently insignificant as…as good manners?

There had been one too many compromises. He knew that much for certain. The buck had needed to stop and it never had. It’d never stopped. So Beede had put on his own brakes and he had stopped. The compromise culture became his anathema. He had shed his former skin (Mr Moderate, Mr Handy, Mr Reasonable) and had blossomed into an absolutist. But on his own terms. And in the daintiest of ways. And very quietly –

Shhh!

Oh no, no, no, the war wasn’t over –

Shhh!

Beede was still fighting (mainly in whispers), it was just that – by and large – they were battles that nobody else knew about. Only Beede. Only he knew. But it was a hard campaign; a fierce, long, difficult campaign. And as with all major military strategies, there were gains and there were losses.

Beede was now sixty-one years of age, and he was his own walking wounded. He was a shadow of his former self. His past idealism had deserted him. And somehow – along the way – he had lost interest in almost everything (in work, in family), but he had maintained an interest in one thing: he had maintained an interest in that old mill.

He had become a detective. A bloodhound. He had sniffed out clues. He had discovered things; stories, alibis, weaknesses; inconsistencies. He had weighed up the facts and drawn his conclusions. But he had bided his time (time was the one thing he had plenty of – no rush; that was the modern disease – no need to rush).

Then finally (at last) he had apportioned blame. With no apparent emotion, he had put names to faces (hunting, finding, assessing, gauging). And like Death he had lifted his scythe, and had kept it lifted; waiting for his own judgement to fall; holding his breath – like an ancient yogi or a Pacific pearl diver; like the still before the storm, like a suspended wave: freeze-framed, poised. He held and he held. He even (and this was the wonderful, the crazy, the hideous part) found a terrible equilibrium in holding.

Beede was the vengeful tsunami of history.

But even the venerable could not hold indefinitely.

‘You know what?’ Kane suddenly spoke, as if waking from a dream. ‘I’d like that.’

Beede didn’t stir from his book.

‘I’d actually like it if you drew me a picture. Do you have a pencil?’

Kane was twenty-six years old and magnificently quiescent. He was a floater; as buoyant and slippery as a dinghy set adrift on a choppy sea. He was loose and unapologetically light-weight (being light-weight was the only thing he ever really took seriously). He was so light-weight, in fact, that sometimes (when the wind gusted his way) he might fly into total indolence and do nothing for three whole days but read sci-fi, devour fried onion rings and drink tequilla in front of a muted-out backdrop of MTV.

Kane knew what he liked (knowing what you liked was, he felt, one of the most important characteristics of a modern life well lived). He knew what he wanted and, better yet, what he needed. He was easy as a greased nipple (and pretty much as moral). He was tall (6' 3", on a good day), a mousy blond, rubber-faced, blue-eyed, with a full, cruel mouth. Almost handsome. He dressed without any particular kind of distinction. Slightly scruffy. Tending towards plumpness, but still too young for the fat to have taken any kind of permanent hold on him. He had a slight American accent. As a kid he’d lived for seven years with his mother in the Arizona desert and had opted to keep the vocal cadences of that region as a souvenir.

‘Come to think of it, I believe I may actually…’

Kane busily inspected his own trouser pockets, then swore under his breath, sat up and glanced around him. A waitress was carrying a tray of clean glasses from somewhere to somewhere else. ‘Excuse me…’ Kane waved at her, ‘would you happen to have a pencil on you?’

The waitress walked over. She was young and pretty with a mass of short, unruly blonde hair pinned back from her neat forehead by a series of precarious-looking, brightly coloured kirby grips. ‘I might have one in my…uh…’

She slid the tray of glasses on to the table. Kane helpfully rearranged his large Pepsi and his cherry danish (currently untouched) to make room for it. Maude (the strangely old-fashioned name was emblazoned on her badge) smiled her thanks and slid her hand into the pocket of her apron. She removed a tiny pencil stub.

‘It’s very small,’ she said.

Kane took the pencil and inspected it. It was minuscule.

‘It’s an HB,’ he said, carefully reading its chewed tip, then glancing over at Beede. ‘Is an HB okay? Is it soft enough?’

Beede did not look up.

Kane turned back to the waitress, who was just preparing to grapple with the tray of glasses again.

‘Before you pick that up, Maude,’ Kane said, balancing his cigarette on the edge of his plate, ‘you wouldn’t happen to have a piece of paper somewhere, would you?’

‘Uh…’

The waitress pushed her hand back into her apron and removed her notepad. She bit her lip. ‘I have a pad but I’m not really…’

Kane put out his hand and took the pad from her. He flipped though it.

‘The paper’s kind of thin,’ he said. ‘What I’m actually looking for is some sort of…’

He mused for a moment. ‘Like an artist’s pad. Like a Daler pad. I don’t know if you’ve heard of that brand name before? It’s like an art brand…’

The waitress shook her head. A kirby grip flew off. She quickly bent down and grabbed it.

‘Oh. Well that’s a shame…’

The waitress straightened up again, clutching the grip.

Kane grinned at her. It was an appealing grin. Her cheeks reddened. ‘Here…’ Kane said, ‘let me…’

He leaned forward, removed the kirby grip from her grasp, popped it expertly open, beckoned her to lean down towards him, then applied it, carefully, to a loose section of her fringe.

‘There…’

He drew back and casually appraised his handiwork. ‘Good as new.’

‘Thanks.’ She slowly straightened up again. She looked befuddled. Kane took a quick drag on his cigarette. The waitress – observing this breach – laced her fingers together and frowned slightly (as if sternly reacquainting her girlish self with all the basic rules of restaurant etiquette). ‘Um…I’m afraid you’re not really…’ she muttered, peeking nervously over her shoulder.

‘What?’

Kane gazed at her. His blue eyes held hers, boldly. ‘What?’

She winced. ‘Smoke…you’re not really meant to…not in the restaurant.’

‘Oh…yeah,’ Kane nodded emphatically, ‘I know that.’

She nodded herself, in automatic response, then grew uncertain again. He passed her the pad. She took it and slid it into her apron. ‘Can I hold on to this pencil?’ Kane asked, suspending it, in its entirety, between his first finger and his thumb. ‘As a keepsake?’

The waitress shot an anxious, side-long glance towards Beede (still reading). ‘Of course,’ she said.

She grabbed her tray again.

‘Thank you,’ Kane murmured, ‘that’s very generous. You’ve been really…’ he paused, weighing her up, appreciatively ‘…sweet.’ The waitress – plainly disconcerted by Kane’s intense scrutiny – took a rapid step away from him, managing, in the process, to incline her tray slightly. The glasses slid around a little. She paused, with a gasp, and clumsily readjusted her grip.

‘Bye then,’ Kane said (not even a suggestion of laughter in his voice). She glanced up, thoroughly flustered. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘of course. Thank you. Bye…’

Then she ducked her head down, grimacing, and fled.

Beede continued reading. It was as if the entire episode with the waitress had completely eluded him.

Kane gently placed the pencil next to Beede’s coffee cup, then picked up his danish and took a large bite of it. He winced as his tooth hit down hard on a stray cherry stone.

‘Shit.’

He spat the offending mouthful into a napkin – silently denouncing all foodstuffs of a natural origin – then carefully explored the afflicted tooth with his tongue. While he did so, he gazed idly over towards the large picture window to his right, and out into the half-empty car park beyond.

‘Expecting someone?’ Beede asked, quick as a shot.

Kane took a second (rather more cautious) bite of the danish. ‘Yup,’ he said, unabashedly, ‘Anthony Shilling.’

‘What?!’

Beede glanced up as he processed this name, a series of conflicting expressions hurtling across his face.

‘I thought you knew,’ Kane said (eyebrows slightly raised), still chewing.

‘How would I know?’ Beede snapped, slapping down his book.

‘Because you’re here,’ Kane said, ‘and why else would you be? It’s miles away from anywhere you’d ever normally go, and it’s a shithole.’

‘I come here often,’ Beede countered. ‘I like it. It’s convenient for work.’

‘That’s just a silly lie,’ Kane sighed, evincing zero tolerance for Beede’s dissembling.

‘Strange as this may seem,’ Beede hissed, ‘I’m actually in no particular hurry to get caught up in some sordid little situation between you and one of my senior work colleagues…’

‘Well that’s a shame,’ Kane said, casually picking up his cigarette again, ‘because that’s exactly what’s about to happen.’

Beede leaned down and grabbed a hold of his small, khaki workbag – as though intending to make a dash for it – but then he didn’t actually move. Something (in turn) held him.

Kane frowned. ‘Beede, why the fuck are you here?’ he asked again, now almost sympathetically.

‘They make a good coffee,’ Beede lied, dropping the bag again.

‘Fuck off. The coffee is heinous,’ Kane said. ‘And just look at you,’ he added, ‘you’re crapping yourself. You hate this place. The piped music is making you nauseous. Your knee is jogging up and down under the table so hard you’re knocking all the bubbles out of my Pepsi.’

Beede’s knee instantly stopped its jogging.

Kane took a quick swig of the imperilled beverage (it was still surprisingly fizzy), and as he placed the glass back down again, it suddenly dawned on him – the way all new things dawned on him: slowly, and with a tiny, mischievous jolt – how unbelievably guarded his father seemed –

Beede?

Hiding something?

His mind reeled back a way, then forwards again –

Hmmn

Beede. This rock. This monolith. This man-mountain. This closed book. This locked door. This shut-down thing.

For once he actually seemed…almost…well, almost cagey. Anxious. Wary. Kane stared harder. This was certainly a first. This was definitely a novelty. My God. Yes. Even in his littlest movements (now he came to think of it): knocking his disposable carton of creamer against the lip of his coffee cup (a tiny splash landing on the spotless nail of his thumb); kicking his bag; picking up his book; fumbling as he turned over the corner of a page, then unfolding it and jumpily pretending to recommence with his reading.

Kane rolled his cigarette around speculatively between his fingers. Beede glanced up for a moment, met Kane’s gaze, shifted his focus off sideways – in the general direction of the entrance (which was not actually visible from where they were seated) – and then looked straight down again.

Now that was odd. Kane frowned. Beede uncertain? Furtive? To actively break his gaze in that way?

What?!

Unheard of! Beede was the original architect of the unflinching stare. Beede’s stare was so steady he could make an owl crave Optrex. Beede could happily unrapt a raptor. And he’d done some pretty nifty groundwork over the years in the Guilt Trip arena (trip? How about a gruelling two-month sabbatical in the parched, ancient Persian city of Firuzabad? And he’d do your packing. And he’d book your hotel. And it’d be miles from the airport. And there’d be no fucking air conditioning). Beede was the hair shirt in human form.

Kane took another swig of his Pepsi –

Okay –

But how huge is this?

He couldn’t honestly tell if it was merely the small things, or if the big things were now also subtly implicated in what he was currently (and so joyously) perceiving as a potentially wholesale situation of emotional whitewash (Oh come on. Wasn’t he in danger of blowing the whole thing out of proportion here? This was Beede for Christsakes. He was sixty-one years old. He worked shifts in the hospital laundry. He hated everybody. The word ‘judgemental’ couldn’t do him justice. If Beede was judgemental then King Herod was ‘a little skittish’.

Beede thought modern life was ‘all waffle’. He’d never owned a car, but persisted in driving around on an ancient, filthy and shockingly unreliable Douglas motorcycle – c. 1942, with the requisite piss-pot helmet. He didn’t own a tv. He found Radio 4 ‘chicken-livered’. He feared the microwave. He thought deodorant was the devil’s sputum. He blamed David Beckham – personally – for breeding a whole generation of boys whose only meaningful relationship was with the mirror. He called it ‘kid-narcissism’…although he still used hair oil himself, and copiously. Unperfumed, of course. He was rigorously allergic to sandalwood, seafood and lanolin; Jeez! An oriental prawn in a lambswool sweater would probably’ve done for him).

Okay. Okay. So Kane freely admitted (Kane did everything freely) that he took so little interest in Beede’s life, in general, that he might actually find it quite difficult to delineate between the two (the big things, the small). He tipped his head to one side. I mean what mattered to Beede? Did he live large? Was he lost in the details?

Or (now hang on a second) perhaps – Kane promptly pulled himself off his self-imposed hook (no apparent damage to knitwear) – perhaps he did know. Perhaps he’d drunk it all in, subconsciously, the way any son must. Perhaps he knew everything already and merely had to do a spot of careful digging around inside his own keen – if irredeemably frivolous – psyche (polishing things off, systematising, card-indexing) to sort it all out.

But Oh God that’d be hard work! That’d take some real effort. And it’d be messy. And he was tired. And – quite frankly – Beede bored him. Beede was just so…so vehement. So intent. So focussed. Too focussed. Horribly focussed. In fact Beede was quite focussed enough for the both of them (and why not add a small gang of Olympic Tri-Athletes, an international chess champion, and that crazy nut who carved the Eiffel Tower out of a fucking toothpick into the mix, for good measure?).

Beede was so uptight, so pent up, so unbelievably…uh…priggish (re-pressed/sup-pressed – you name it, he was it) that if he ever actually deigned to cut loose (Beede? Cut loose? Are you serious?!) then he would probably just cut right out (yawn. Again), like some huge but cranky petrol-driven lawnmower (a tremendously well-constructed but unwieldy old Allen, say). I mean all that deep inner turmoil…all that…that tightly buttoned, straight-backed, quietly creaking, Strindberg-style tension. Where the hell would it go? How on earth could it…?

Eh?

Of course, by comparison – and by sheer coincidence – Kane’s entire life mission –

Oh how lovely to hone in on me again

– was to be mirthful. To be fluffy. To endow mere trifles with an exquisitely inappropriate gravitas. Kane found depth an abomination. He lived in the shallows, and, like a shark (a sand shark; not a biter), he basked in them. He both eschewed boredom and yet considered himself the ultimate arbiter of it. Boredom terrified him. And because Beede, his father, was so exquisitely dull (celebrated a kind of immaculate dullness – he was the Virgin Mary of the Long Hour) Kane had gradually engineered himself into his father’s anti.

If Beede had ever sought to underpin the community then Kane had always sought to undermine it. If Beede lived like a monk, then Kane revelled in smut and degeneracy. If Beede felt the burden of life’s weight (and heaven knows, he felt it), then Kane consciously rejected worldly care.

A useful (and gratifying) side-product of this process was Kane’s gradual apprehension that there was a special kind of glory in self-interest, a magnificence in self-absorption, a heroism in degeneracy, which other people (the general public – the culture) seemed to find not only laudable, but actively endearing.

Come on. Come on; nobody liked a stuffed shirt; nobody found puritanism sexy (except for Angelo who wanted to shag Isabella in Measure for Measure. But Shakespeare was a pervert; and they didn’t bother teaching you that in O-level literature…); nobody – but nobody – wanted to stand next to the teetotaller at the party –

Hey! Where’s the guy in the novelty hat with the six pack of beer?

Kane half-smiled to himself as he took out his phone, opened it, deftly ran through his texts, closed it, shoved it back into his pocket, took a final drag on his cigarette and then stubbed it out.

‘So what’s that you’re reading?’

He picked up his lighter (a smart, silver and red-enamelled Ronson) and struck it, lightly –

Nothing.

After an almost interminable six-second hiatus, Beede closed his book and placed it down – with a small sigh – on to his lap. ‘Whatever happened to that girl?’ he asked mechanically (having immediately apprehended the fatuous nature of Kane’s literary enquiry). Kane frowned –

Wow…

To answer a question with a question –

Masterly.

‘Girl?’ Kane stared back at him, blankly. ‘Which girl? The waitress?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ Beede snapped. ‘The little girl. The skinny one. I haven’t seen her around in a while…’

‘Skinny?’

Kane adopted a look of cheerful bewilderment.

‘The redhead,’ Beede persisted (thoroughly immune to Kane’s humbug). ‘Too skinny. Red hair. Bright red hair…’

‘Red hair?’

‘Yes. Red hair. Purple-red…’

‘Purple?’

‘Yes…’ (Beede yanked on his trusty, old pair of mental crampons and kicked them, grimly, into the vertical rockface of his self-control).

‘Yes. Purple.’

Kane didn’t seem to notice.

‘Purple?’ he repeated, taking some time out to savour the feel of this word on his tongue –

Purple

Purrrrr-pull

– then glancing up –

Ooops

– and relenting. ‘You probably mean Kelly,’ he vouchsafed, almost lasciviously. ‘Little Kelly Broad. Lovely, filthy, skinny, little Kelly…’

‘Kelly Broad. Of course,’ Beede echoed curtly. ‘So are the two of you still an item?’

An item? Kane smirked at this quaint formulation. ‘Hell, no…’ he took a long swig of his Pepsi, ‘that’s all…’ he burped, ‘excuse me…totally fucked now.’

Beede waited, patiently, for any further elucidation. None was forthcoming.

‘Well that’s a pity,’ he finally murmured.

‘Why?’ Kane wondered.

Beede shrugged, as if the answer was simply obvious.

‘Why?’ Kane asked again (employing exactly the same maddening vocal emphasis as before).

‘Because she was a decent enough girl,’ Beede observed stolidly, ‘and I liked her.’

Kane snorted. Beede glanced up at him, wounded. He took a quick sip of his coffee (in the hope of masking any further emotional leakage), then – urgh – winced, involuntarily.

‘Tasty?’ Kane enquired, with an arch lift of his brow. Beede placed the cup back down, very gently, on to its saucer. Kane idly struck at his lighter again –

Nothing.

‘So you think I had a problem with her?’ Beede wondered, out loud, after a brief interval.

‘Pardon?’ Kane was already thoroughly bored by the subject.

‘A problem? You mean with Kelly? Uh…’ He gave this a moment’s thought. ‘Yes. Yes. I suppose I think you did.’

Beede looked shocked.

Kane chuckled. ‘Oh come on…’

‘What?’

‘You oozed disapproval.’

‘Did I?’

‘Through every conceivable orifice.’

Beede’s nostrils flared at this cruel defamation, but he drew a long, deep breath and swallowed down his ire.

‘Okay. Okay…’ he murmured tightly. ‘So what do you think I “disapproved” of exactly?’

Kane threw up his hands. ‘Where to begin?’

Beede folded his arms. Kane duly noted the folding. ‘All right then,’ he volunteered, ‘you thought she was a tart.’

Beede blinked –

Tart?

‘You know…’ Kane’s voice adopted the tender but world-weary tone of an adult describing something simple yet fundamental to a wayward toddler – like how to eat, how to walk (‘So you put one foot…that’s it, one foot, very slowly, in front of the other…’)‘…a tart; a harlot, a strumpet, a whore…’

Beede opened his mouth to respond, but Kane barrelled on, ‘Although you shouldn’t actually feel bad about it. I was fine with it. In fact – if anything – it was an incentive of sorts…I mean romantically.’

He paused for a second, musing. ‘Isn’t it odd how the disapproval of others can often contribute so profoundly to one’s enjoyment of a thing?’

Beede opened his mouth to answer.

‘Tarts especially,’ Kane interrupted him.

‘Well she certainly dressed quite provocatively…’ Beede ruminated.

Kane waved this objection aside. ‘Nah. It was all just an act. Smoke and mirrors. A total fabrication. She was a sweetheart, an innocent. Her bad reputation was down to nothing more than a couple of stupid choices and some bad PR.’

‘But you still broke up with her,’ Beede needled.

Kane shrugged.

‘Indicating that perhaps – at some level – it did actually bother you?’

‘No,’ Kane shook his head. ‘It wasn’t ever a question of virtue with Kelly. It was simply an issue of trust.’

‘Ah-ha…’ Beede pounced on this idea, greedily. ‘But isn’t that the same issue?’

‘Absolutely not.’

Kane smiled at his father, almost fondly, as if touched – even flattered – by the unexpectedly intrusive line of his questioning. ‘She wasn’t a tart. Not at all. But she was a thief, which is a quality I find marginally less endearing.’

Beede seemed taken aback by this piece of information.

‘She stole? What did she steal?’

‘Huh?’

Kane’s attention was momentarily diverted by a sudden commotion outside in the car park.

‘I said what did she steal?’

Kane struck his lighter again –

Nothing

‘You really want to know?’ he murmured.

‘I just asked, didn’t I?’

‘Yes. Yes you did…’ He sighed. ‘She stole tranquillisers, mainly; Benzodiazepines…’

Kane struck his lighter for a final time and on this occasion a flame actually emerged and it was a full 5 inches high (he always set his lighters at maximum flare, even if his fringe paid the ultimate price for his profligacy).

‘…Some Xanax. Some Valium. Some…’

He paused, abruptly, mid-enumeration –

‘Holy shit!’

The flame cut out.

A man.

There was a man.

There was a man at the window, gazing in at them. And he was perched on a horse; an old, piebald mare (the horse wore no saddle, no reins, but he sat astride her – holding on to her mane – with absolute confidence). He was a strange man; had a long, lean, pale-looking face underpinned by a considerable jaw, grey with stubble; a mean mouth, sharp, dark eyes, thick, brown brows but no other hair to speak of. His head was cleanly shaven. He was handsome – vital, even – but with a distinctly delinquent air. He was wearing something strangely unfeasible in a bright yellow (a colour of such phenomenal intensity it’d cheerfully take the shine off a prize canary).

The window was horse-high, only; its torso banged against the glass, steaming it over – so the man leaned down low to peek in, as if peering into the tank of an aquarium (or a display cabinet in a museum). Kane couldn’t tell – at first – what exactly it was that he was looking for, but he seemed absolutely enthralled by what he saw (seemed to take delight in things – like a child – quite readily). He was smiling (although not in an entirely child-like way), and when his eyes alighted upon Kane, the smile expanded, exponentially (small, neat, yellowed teeth, a touch of tongue). He reached out a hand and beckoned towards him –

Come

Kane dropped his lighter.

As the lighter hit the table-top Beede turned himself and followed the line of Kane’s gaze. His own eyes widened.

The horseman kicked at the mare’s flanks and pulled away. There was a thud of hooves on soil (God only knows what havoc he’d wreaked on the spring flower display in the bed below the window) and then a subsequent musket-clatter on the tarmac.

Kane shoved back his chair and stood up. ‘Is the fucking carnival in town or what?’ he asked (noticing the quick pump of his heart, the sharp flow of his breath). He’d barely finished speaking (was about half-way to the window to try and see more) when a woman walked into the room. She was holding on to the hand of a small boy. She appeared to be searching for someone.

This time it was Beede’s turn to spring to his feet. The book on his lap fell to the floor. Kane spun around to the sound of its falling. ‘Elen!‘ Beede exclaimed, his face flushing slightly.

The woman did not acknowledge him at first. She merely paused, glanced from Beede to Kane, then back again, her expression barely altering (it remained bright and calm and untroubled. Almost serene). Kane saw that she had a large birthmark – a brown mole – in the curve of her nose, just to the right of her left eye, but it disappeared from view as a sheet of long, dark hair slipped out from behind her ear.

‘Did Isidore bring you here?’ Beede asked, trying (and almost succeeding) to sound less emotionally involved than before. She looked a little surprised as she pushed back her hair. ‘Of course not,’ her lips pursed together in a brief pucker of concern, ‘he’s at work today.’

She had a soft voice. The accent wasn’t Ashford but it was too vague for Kane to place it. As she spoke she released the boy’s hand. The boy walked straight past Kane and over to the window, but instead of looking through it (he was a little short for this, anyhow), he turned, shoved his back against the wall, and pulled the curtain across the top half of his body (thereby casually obscuring what remained of Kane’s view). Kane scowled (only the bottom half of the boy’s torso was now visible), glancing from the curtain and back to Beede again. ‘Did you see that creature out there?’ he asked, his head still full of what’d happened before.

‘This is my son, Kane,’ Beede murmured to the woman, in a light, almost excessively straightforward way.

The woman nodded at Kane. She smiled slightly. She was very lean. Her clothes were long and hippyish, but dark and plain and clean.

‘Elen is my chiropodist,’ Beede explained.

‘Hi,’ Kane muttered, glancing distractedly towards the window again, focussing in on the boy, who – quiet as he remained – was rather difficult to ignore.

‘Fleet,’ the woman said – her voice mild but authoritative – ‘please come away from there.’

‘I owed Elen some money,’ Beede continued (almost to thin air). He put his hand to his pocket, then thought better of it and leaned down to pick up his bag from the floor.

Kane noticed how he pronounced her name – not Ellen, but E-len – as if the ‘l’ had quite bewitched his tongue.

The boy ducked out from under the curtain (leaving it drawn), walked back over to his mother and stood at her side. He was small and wild-looking (four years old? five?); an imp; round-faced and wide-lipped, with pale skin, brown freckles and black hair. He stared at Kane, unblinking. Then he smiled. He had no front teeth.

‘We were waiting in the bar area,’ the woman said, glancing for a moment towards the window herself (as if sensing Kane’s preoccupation with it). ‘Fleet found a counter on the floor and put it into one of the machines. He won some money.’

The boy jiggled his hands around in his pockets and gurgled, delightedly.

‘The barman said he was underage…’

‘He is,’ Beede interrupted.

Kane rolled his eyes, then displaced his irritation by taking out his phone and checking his texts again. The woman observed Kane’s irritation, but showed no reaction to it.

‘He gave me all of these,’ Fleet interjected, pulling several packets of complimentary matches from his pockets, laughing and rotating on the spot, his face turned up to the ceiling, the matches clutched tightly to his chest. His mother put out her hand to steady him. ‘He builds things with them,’ she explained.

Outside the horse was still vaguely audible as it moved around in the car park. While Beede continued to search through his bag, Kane strolled over to the window, pulled the curtain back and peered out. The horse was visible, but way off to his left. It had come to a halt in the children’s play area, where it stood, breathing heavily and defecating. The man was now struggling to climb off its back. But it was an entirely different man.

Kane blinked.

Entirely different. Tall. Nordic. Smartly dressed in some kind of uniform –

Imposter

He pushed his palms up against the glass and looked around for the canary-coated stranger, but nobody else was visible out there.

‘How strange,’ he said, turning just in time to see Beede’s hand withdrawing from the woman’s hand (he had passed her an envelope. She placed it into her bag, her eyes meeting Kane’s, calmly).

‘What is?’ Beede asked.

‘The man who peered in through the window a moment ago. The man on the horse. He’s changed.’

‘How do you mean?’

‘He had a shaved head and a thin face. He was dressed in yellow.’

The boy suddenly stopped revolving. He grabbed on to his mother’s skirts. ‘Oh dear,’ he whispered, then pushed his face deep into the fabric and kept it hidden there.

The child was definitely beginning to work on Kane’s nerves.

Beede was staring at Kane, but his expression was unreadable (was it disbelief? Was it irritation? Anger? What was it?) The woman merely stared at the ground, frowning, as if carefully considering something.

‘Did you see him?’ Kane asked again.

‘Uh…no. No. And I’m late – work. I’d better head off.’ Beede spoke abruptly. He touched the woman’s sleeve (she smiled), ruffled the boy’s hair (the boy released his mother’s skirt and gazed up at him), slung his bag over his shoulder, grabbed his helmet, his goggles, and rapidly strode off.

Kane watched him go, blankly. Then he blinked (something seemed to strike him) and he focussed –

What?!

Beede disappeared from view.

‘Is anything the matter?’ the woman asked, observing Kane’s sudden air of confusion.

He turned to look at her. ‘No.’ He put his hand to his head.

‘Yeah.’ He removed his hand. ‘No…It’s just that…’ he paused, ‘Beede…There’s something…something odd.’

She nodded, as if she understood what he meant.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

She smiled (that smile again) but didn’t answer.

‘Do you know?’

He struggled to mask his irritation. She folded her arms across her chest and nodded again, now almost teasing him.

‘Then what is it?’

‘His walk,’ she said, plainly.

Kane drew a sharp breath. ‘His limp,’ he exclaimed (as if this information had come to him entirely without prompting). ‘He’s lost his limp.’

‘Yes.’

‘But how…? When?’

‘A while ago now.’

‘Really?’

She nodded. Kane scratched his jaw –

Two days’ growth

He felt engulfed by a sudden wave of feeblemindedness –

Too tired

Too stoned

Too fucked…

He looked at her, hard, as if she might be the answer to his problem –

Chiropodist

‘Did you get rid of it?’ he asked.

She smiled, her eyes shining.

Kane rubbed at his own eyes. He felt a little stupid. He steadied himself.

‘Beede’s had that verruca since I was a kid,’ he said slowly. ‘It was pretty bad.’

‘I believe it was very painful,’ she said, still smiling (as if the memory of Beede’s pain was somehow delightful to her).

He coldly observed the smile –

Is she mocking him?

Is she mocking me?

– then he gradually collected his thoughts together. ‘Yes,’ he said stiffly, ‘I have one in almost exactly the same place, but it’s never really…’

His words petered out.

She shrugged. ‘People often inherit them. It’s fairly common. Verrucas can be neurotic…’

‘Neurotic?’

Kane’s voice sounded louder than he’d intended.

‘Yes,’ she was smiling again, ‘when a patient fails to get rid of something by means of conventional medicine we tend to categorise it as a psychological problem rather than as a physical one.’

Kane struggled to digest the implications of this information. His brain seized, initially, then it belched –

‘But a verruca’s just some type of…of wart,’ he stuttered. ‘You catch them in changing rooms…’

‘Yes. But like any ailment it can be sustained by a kind of…’ she paused, thoughtfully ‘…inner turmoil.’

The boy was now sitting on the floor and inspecting his matches. He shook each box, in turn, and listened intently to the sounds it made. ‘I can tell how many’s in there,’ he informed nobody in particular, ‘just from the rattlings.’

‘We’ve met before.’ Kane spoke, after a short silence.

‘Yes,’ she said.

(He already heartily disliked how she just agreed to things, in that blank – that untroubled – way. The easy acquiescence. The cool compliance. He connected it to some kind of background in nursing. He loathed nurses. He found their bedside manner – that distinctively assertive servility – false and asphyxiating.)

‘You treated my mother,’ he said, feeling his chest tighten. She sat down on Beede’s chair, facing him. ‘I think I did. Years ago.’

‘That’s right. You came to the house. I remember now.’

They were both quiet for a moment.

‘You’d just returned from Germany,’ Kane continued, plainly rather astonished (and then equally irritated) by the extent of his own recall.

‘Yes I had. I went there for a year, almost straight after I’d graduated.’

‘I remember.’

He sniffed, trying to make it sound like nothing.

‘You have an impressive memory,’ she said, then put a polite hand up to her mouth, as if to suppress a yawn. This almost-yawn infuriated him. He didn’t know why.

How old was she, anyway? Thirty-one? Thirty-three?

‘No,’ he said. ‘It’s just your mole. Your birthmark. It’s extremely memorable.’

She didn’t miss a beat.

‘Of course,’ she said.

‘I’m sorry,’ he struggled to repress a childish smile, ‘that must’ve sounded rude.’

‘No…’ she shook her head, her voice still soft as ever, ‘it didn’t sound rude.’

Didn’t sound rude.

Kane stared at her. She stared back at him. He took out his phone and inspected his messages.

‘A psychiatrist,’ she observed mildly, ‘might call what you do with that phone “masking behaviour”.’

He glanced up, astonished –

The cheek of it

– then quickly checked himself. ‘I guess they might,’ he said, returning casually to his messages and sending a quick response to one of them, ‘but then you’re just a foot doctor.’

She chuckled. She didn’t seem at all offended. ‘You have eyes just like your father’s,’ she murmured, gracefully adjusting the long hem of her skirt (as if hers was a life without technology, without chatter. A life entirely about thinking and pausing and feeling. A quiet life). Kane’s jaw stiffened. ‘I don’t think so,’ he murmured thickly, ‘they’re a completely different colour.’

She shrugged and then sighed, like he was just a boy. She glanced down, briefly, at her son (as if, Kane felt, to make the connection 100 per cent sure), then said blandly, ‘It was a difficult time for you.’

‘Pardon?’

He put his phone away. The tone of his voice told her not to persist, but she ignored the warning.

‘Difficult. With your mother. I remember thinking how incredibly brave you were. Heroic, almost.’

His cheeks reddened. ‘Not at all.’

‘Sometimes, after I’d seen her, I’d just sit in my car and shake. Just shake. I didn’t know how you coped with it. I still don’t. You were so young.’

She smiled softly at the memory, and as she smiled, he suddenly remembered. He remembered standing at the window and seeing her in her car, shaking: her arms thrown over the steering wheel, her head thrown on to her arms –

Oh God

His gut twisted.

He turned and gazed out into the car park. He was unbelievably angry. He felt found-out – unearthed – raw. But worst of all, he felt charmless. Charm was an essential part of his armoury. It was his defensive shield, and she had somehow connived to worm her way under it –

Damn her

He drew a deep breath.

Outside he could suddenly see Beede –

Huh…?

– walking through the play area towards the blond imposter and the horse. The imposter had now dismounted. He was touching his head. He seemed confused. Beede offered his hand to the horse. The horse sniffed his hand. It appeared very receptive to Beede’s advances.

‘I wonder what happened to the other man,’ Kane mused, then shuddered. Everything was feeling strange to him. Inverted. And he didn’t like it.

‘Maybe there were two horses,’ the boy said. He was now standing next to the table and fingering Kane’s lighter. He looked up at Kane and held it out towards him. ‘Red,’ he smiled, ‘that’s your colour.’ The lighter was red.

He showed his mother. ‘See?’

She said nothing.

‘See?’ he repeated. ‘He comes from fire.’

‘Don’t be silly.’ His mother took the lighter off him and held it out to Kane herself.

Kane walked over and took it from her. She had beautiful hands. He remembered her hands from before.

‘I lived in the American desert,’ he said to the boy, ‘when I was younger. It was very hot. I once almost died in the heat out there. Look…’

He pushed back his sleeve and showed the boy a burn on his arm. The boy seemed only mildly interested.

Kane was about to pull his sleeve down again when the woman (Elen, was it?) put out her hand and took a firm hold of his wrist. She pulled his arm towards her. She stared at the scar. Her face was so close to it he could feel her breath on his skin. Then she let go (just as suddenly) and focussed in on the boy once more.

‘America,’ Kane said, taking full possession of his arm again, drawing it into his chest, shoving the sleeve down, feeling like an angry child who’d just had his school uniform damaged in a minor playground fracas. As he spoke he noticed Beede’s book on the floor. He bent down and picked it up. He shoved it into his jacket pocket.

‘In a magic trick,’ the boy repeated, plaintively, ‘they would’ve had two horses.’

‘How old are you?’ Kane asked, glancing over towards the serving counter and noticing Anthony Shilling standing there.

‘Five.’

‘Then you’re just old enough to keep it…’ he said, showing Fleet his empty hand, forming a fist, tapping his knuckles and then opening the hand up again. The red lighter had magically reappeared in the centre of his palm. The boy gasped. Kane placed it down, carefully, on to the lacquered table, nodded a curt farewell to the chiropodist, and left it there.

TWO (#ulink_6ae14bad-cbf8-5c57-8a78-1a4a430f3183)

‘I’m Beede; Daniel Beede. I’m your friend. Do you remember me, Dory?’

Beede peered up, intently, into the tall, blond man’s face, struggling – at first – to establish any kind of a connection with him. He spoke softly (like you’d speak to a child) and he used his name carefully, as if anticipating that it might provoke some kind of violent reaction. But it didn’t.

‘Of course.’

The tall, blond man blinked and then nodded. ‘Yes. Yes, of course I remember…’ He talked quietly and haltingly with a strong German accent. ‘It’s just that…uh…’

His eyes anxiously scanned the surrounding area (the road, the horse, the tarmac, the vehicles in the car park). ‘It’s just that I suddenly have the strangest…’

He winced, shook his head, then gazed down, briefly, at his own two hands, as if he didn’t quite recognise them. ‘…uh…fu…fu…fühlen?’

He glanced up, quizzically.

‘Feeling,’ Beede translated.

The German stared at him, blankly.

‘Feeling,’ Beede repeated.

The German frowned. ‘No…not…it’s this…this…’ he patted his own chest, meaningfully, ‘fuh-ling. Feee…Yes. Yes. This feeling. This horrible, almost…’ he shuddered, ‘almost overwhelming feeling. Like a kind of…’ He swallowed. ‘A dread. A deep dread.’

Beede nodded.

‘…a terrible dread.’ He moved his hands to his throat, ‘Suffocare. Suffocating. A smothering feeling. A terrible feeling…’

‘You’re tired,’ Beede murmured gently, ‘and possibly a little confused, but it’ll soon pass, trust me.’

‘I do,’ the German nodded, ‘I do traust you.’ He paused. ‘Trost you…’

He blinked. ‘Troost.’

‘Trust,’ Beede repeated.

‘Of course…’ the German continued. ‘It’s just…’

His darting eyes settled, momentarily, on the pony. ‘I have an awful suspicion that this feeling – this…this…uh…’

‘Fear,’ Beede filled in, dryly.

‘Yes…yes…fff…’

The German attempted to wrangle the familiar syllable on his tongue – ‘Ffffah…’ – but the word simply would not come. After his third unsuccessful attempt (pulling back his lips, like a frightened chimpanzee, his nostrils flaring, his eyes bulging) he scowled, closed his mouth again, paused for a second, took stock, then suddenly, and without warning, threw back his head and roared, ‘GE-FHAAAAR!’ at full volume.

The horse skipped nervously from foot to foot.

‘Urgh…’

The German grimaced, wiped his chin with his cuff, then closed his eyes and drew a deep breath. On the exhale he repeated the word – ‘Gefhaar’ – but much more softly this time. He smiled to himself and drew another breath. ‘Fhaar,’ he sighed, then (with increasing rapidity), ‘Fhaar-fhar-fhear-fear-fear…Yes!’

His eyes flew open, then he scowled. ‘But what am I saying here?’

‘This fear,’ Beede primed him.

‘Yes. Of course. Fear. This fear’

The German rapidly clicked back into gear again. ‘I have a feeling – a…a suspicion, you might say – that this dread, this…this…this fhar may be linked in some way…connected in some way…’ he jinked his head towards the pony, conspiratorially ‘…to it. To that. To…’ he struggled to find the correct noun, ‘to khor-khor-khorsam…’

He shook his head, scowling. ‘Khorsam. Horsam. Hors. Horse. Horsey. Horse. Horses.’

He glanced over at Beede, breathlessly, for confirmation. Beede nodded, encouragingly.

‘But you see I’m not…I can’t be entirely…uh…certus,’ he scowled, then winced, then forged doggedly onward, ‘certanus…’ He paused. ‘Cer-tan. I can’t be certain, because it’s still just an…an inkling…’ he shuddered ‘…a slight shadow in the back of my mind. A hunch. Nothing more.’

While he spoke he distractedly adjusted the wedding band on his finger (twisted it, as if of old habit), then gradually grew aware of what he was doing and glanced down. ‘What’s this?’

His eyes widened. ‘A ring? A gold ring? On my third finger?’

He glared at Beede, almost accusingly. ‘Can that be right?’

Beede nodded. He seemed calm and unflustered; as if thoroughly accustomed to this kind of scenario.

‘Mein Gott!’ The German’s handsome face grew stiff with incredulity.

‘You’re telling me I’m…I’m…’

‘Married?’ Beede offered. ‘Yes. Yes, you are. Very happily.’

‘Seriously?’

‘Just wait a while,’ Beede patted his arm, ‘and everything will become clear. I promise.’

‘You’re right. You’re right…’ the German smiled at him, gratefully, ‘I know that…’

But he didn’t seem entirely convinced by it.

‘So do you have any thoughts on where the horse may’ve came from?’ Beede enquired, gently stroking the mare’s flanks. She was exhausted. Her tongue was protruding slightly. There were flecks of foam on her neck and her ribcage. He was concerned that someone inside the restaurant might see them (a member of staff – the manager). They were in a children’s play area, after all. The horse was plainly stolen. Did this qualify as trespass?

The German closed his eyes for a moment (as if struggling to remember), and then the tension suddenly lifted from his face and he nodded. ‘I see a field in the middle of two roads, curving…’ he murmured softly, his speech much less harsh, less halting than before, ‘and beyond…beyond I see Romney. I see the marshes. ‘

He opened his eyes again. ‘I was checking over a couple of vacant properties earlier,’ he explained amiably, ‘in South Willesborough…’

Then he started –

‘Eh?!’

– and spun around, as though someone had just whispered something detestable into his ear.

‘WHO SAID THAT?!’ he cried.

‘Who said what?’

Beede’s voice was tolerant but slightly teachery.

‘About…About South Willesborough…?’ He continued to look around him agitatedly. ‘Was it you? Did you speak? Were you there earlier?’

‘Hmmn. A field in the middle of two roads curving…’ Beede mused (pointedly ignoring the German’s questions), ‘I think I know the place. And it’s not too far. Perhaps a mile – a little more. We’ll need to lead her back quickly. Someone might miss her. Do you have a belt?’

The German peered down at himself. ‘Yes,’ he said, and automatically started to unfasten the buckle.

‘I’ll take mine off, too,’ Beede said, unfastening his own.

The German pulled his belt free, passed it over, then tentatively sniffed at the arm of his jacket. ‘Urgh!’ he croaked. ‘What on earth have I been doing? I smell disgusting, and look – look – I have horse hair simply everywhere…’

He began frantically patting and slapping at the fabric, but after a couple of seconds he froze – mid-slap – as something terrible dawned on him. ‘Oh Christ,’ he gasped. ‘Oh Jesus Christ – the car. Where’s the car? What on earth have I done with it?’

Beede had buckled the two belts together. He whispered soothingly into the mare’s ear and then looped them around her neck. She was a sweet filly. She nodded a couple of times as he pulled the leather tighter.

On the second nod – and completely without warning – the German sprang back with a loud yell. The horse took fright and reared up. Beede clung on, resolutely.

‘Hey, hey…’ he hissed (managing – rather miraculously – to rein in both the horse and his temper), ‘just calm down, Dory. She won’t hurt anybody. She’s worn out. Let’s try and hold this situation together, shall we?’

‘But I hate horses,’ the German whimpered, hugging himself, tightly (the way a frightened girl might), and gazing up at the horse with a look of sheer, unadulterated terror. ‘I absolutely…I…I loathe them…’

‘That’s fine,’ Beede interrupted, ‘I’ll lead the horse, see?’

Beede led the horse two steps forward. ‘The horse is fine. Everything’s fine. There’s no need to panic. Everything’s just fine here.’

But the German was still panicking. ‘Oh God,’ he wailed, ‘if I’ve lost the car they’ll sack me for sure. Then where will we be?’

‘You won’t have lost it,’ Beede said determinedly.

‘Why?’ He grew instantly suspicious. ‘How do you know? How can you be sure? Were you there?’

‘No. No, I was here,’ Beede pointed towards the French Connection, ‘I was in the restaurant. I was having a coffee with my son. My son is called Kane. He’s still inside, actually.’

As he pointed, Beede glanced over towards the window where Kane had stood previously. The window was empty. ‘Coffee?’ The German peered over towards the window, scowling – ‘Coffee?’ – but then something powerful suddenly seemed to strike him – a revelation – ‘But of course!’ he gasped. ‘Kaffee… kaff…kaff… Koffee. Coffee. I remember that. I know that. I know kaffee…’

He put a tentative – almost fearful – hand up to his own chin and gently explored it with the tips of his fingers. Then he smiled (it was a brilliant smile), then he gazed at Beede, almost in wonder.

‘Beede,’ he said, rolling the name around in his mouth like a boiled toffee. Then he clutched at his stomach (as if the memory had just jabbed him there), leaned sharply forward and took a quick, rasping gulp of air –

Oh God –

Oh God

Just to be…to be…to be…

He stared around him, quite amazed –

Where?

‘Of course,’ Beede smiled back, clearly relieved by this sudden show of progress (tastes and smells, he found, were often the key), ‘of course you remember…’

He placed a reassuring hand on to the German’s broad shoulder. ‘Now – deep breath, deep breath – are you ready? Shall we get the hell out of here?’

Kelly Broad was sitting on a high wall, chewing ferociously on a piece of celery. She was passably pretty and alarmingly thin with artificially tinted burgundy hair –

Because I’m worth it

Her face was hard (but with an enviable bone-structure), her ‘look’ was urban – hooded top (hood worn up), combat mini-skirt and a pair of modern, slightly scuffed, silver trainers (the kind astronauts wore – devoutly – whenever they went jogging above the atmosphere). No socks (not even the ones you could buy which made it look like you weren’t wearing any – the half-socks you got at JD Sports or Marks & Spencer).

Her legs were bare and white and goose-bumping prodigiously. But she didn’t feel the cold. She had bad circulation, weak bones (fractured both her wrists when she was nine in a bouncy-castle misadventure. Earned herself a tidy £3,000 in compensation, and the whole family got to spend three weeks in Newquay; her gran lived there), a penchant for laxatives and an Eating Disorder –

Might as well bring that straight up, eh?

Un,

Deux,

Trois…

Bleeeaa-urghhh!

Although her eating habits (if you wanted to get pedantic about it – and Kelly did, because she was) were ridiculously orderly (the Weight Watchers’ manual was her bible; she drew up a special weekly menu and stuck to it religiously, counted every calorie, took tiny mouthfuls, ate with tiny cutlery – just like Liz Hurley), so it wasn’t actually a problem, as such; more of a…a preference, really. She simply preferred her food fat-free. It was a Life-Style decision (the kind of thing they were always banging on about in magazines and on the telly), and so all perfectly legitimate (especially when your own mother was too big to cram herself into an average-size car-seat – used the disability section on the bus – belly arrived home seven seconds before her arse – hadn’t seen her toes since 1983 – Feet? They had their own fucking passports down there).

Kelly came from a bad family.

No. No. That was just too easy. They weren’t bad as such (no, not bad) so much as…as known…as familiar…as…as –

Notorious

That was it

And only locally. Only in Ashford –

Well…

– and maybe in Canterbury. And Gillingham (where her older sister Linda supported The Gills – I mean really supported them – with a fist-guard, business cards, a retractable-blade). And in parts of Folkestone. And Woodchurch. And some of those smaller places which didn’t really matter (except to the people living there).

In the local vicinity, basically. It wasn’t national or anything (no special reports on Crimewatch UK – aside from a small, pointless item on Network South East – November 2001. And that didn’t really count. It was probably just a quiet day – a craft fair had been rained off in Sheppey or something – and they had to fill up the time somehow, didn’t they? Yeah. So the Broads copped it again – Uncle Harvey; Dad’s oldest brother; the world’s shonkiest builder –

Blah blah).

Notorious.

Like the Notorious B.I.G. The rapper. That fat American dude who got shot –

Bang

– dead. And then they made a documentary about him. And she’d watched it. And they’d said that he was actually a really nice guy (underneath. But fat. Very fat. That was partly what he was famous for. That’s essentially what the BIG stood for). And his mamma loved him (which had to count for something). And when he died they made a tribute song for him. With Sting. And Puff Da – Di – Daddy.

Notorious.

Isn’t that what Ashford people –

Gossips

Wankers

– liked to call the Broads? Wasn’t that the word they preferred?

Kelly sniffed.

Did it have to be a negative?

Notorious?

As in train robber?

As in sex offender?

She pinched some pearlescent pink lipstick from the corners of her mouth.