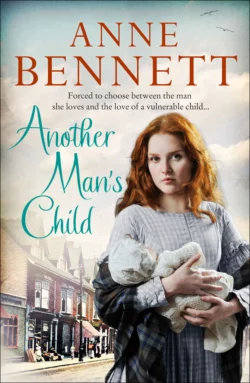

Another Man’s Child

Anne Bennett

A moving family drama of one young woman’s fight to survive, to find her long-lost relatives and to find a place to call homeCelia Mulligan is in love with farm hand Andy McCadden, but when Andy asks her to marry him and she accepts, her father is furious – no daughter of his will marry a mere hireling. Celia elopes with Andy and they make their way by ship to England. While on board, Celia meets a demure young woman called Annabel who tells her in confidence that a friend of her father forced himself upon her and she has since fallen pregnant.Annabel plans to throw herself on her brother’s mercy and asks Celia if she will accompany her to Birmingham as her ladies maid. Without a job and with nothing to offer her, Andy encourages Celia to accept – he can find employment for himself and save for their future. But neither of them can foresee the events that will follow, and soon Celia will be forced to choose between the man she loves, and the love of a vulnerable child…

Copyright (#ua3d88705-3cbb-5370-877f-26d91e3d1aaa)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

A Paperback Original 2015

1

Copyright © Anne Bennett 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Gordon Crabb (woman and baby); Birmingham Museum Trust (street scene)

Anne Bennett asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cottage photograph © Martin Logue

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007359271

Ebook Edition © November 2015 ISBN: 9780007383276

Version: 2017-09-08

Dedication (#ua3d88705-3cbb-5370-877f-26d91e3d1aaa)

I dedicate this book to my cousins, Martin Logue of Redditch in the West Midlands, and Michael Mulligan from Dublin, with all my love and best wishes.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u2598a6cc-f739-5f10-b49d-d66991cb331b)

Title Page (#ue2395cc4-c9f9-5b04-9b2d-e2d9d7879616)

Copyright (#uaa893968-c9a5-5cd0-a4e0-5004dfcd312f)

Dedication (#u8d598a67-0625-5109-97b9-d516d30f4d83)

Chapter One (#u516494a9-43a5-5066-897b-30c997fee738)

Chapter Two (#uc077da20-1d08-5626-9e80-84e44e6c8432)

Chapter Three (#u08353de3-300c-5d7a-ac06-8dad3a4b2112)

Chapter Four (#ua914ddfe-7110-5f27-985a-1cec27fe0ef3)

Chapter Five (#u60e9c1c2-3269-5744-bda0-ece91f711884)

Chapter Six (#u517ae9f5-49e9-5083-9fa0-48ddf1ad59de)

Chapter Seven (#u63e605e6-c0b5-5ed5-a579-a0297c03aa88)

Chapter Eight (#ua2e36e4c-264c-5e56-8397-d2a8cdd47ed4)

Chapter Nine (#ub6d5259f-81fe-550d-af5d-215e304e6308)

Chapter Ten (#u13b8a453-b36c-5ba2-a80d-1ce3a0a5a169)

Chapter Eleven (#ud3b08fc0-98fc-5235-8042-c7b7be69a328)

Chapter Twelve (#u053f3a59-cb86-53d2-96c7-90173e86c4a9)

Chapter Thirteen (#ue7fd972d-87cc-51dd-93a4-30d896d15680)

Chapter Fourteen (#u9a473edf-2876-53b6-9c62-d71e36e7cecd)

Chapter Fifteen (#u1bd9b2f4-c35a-51d0-a1cd-20191784eaf0)

Chapter Sixteen (#u8d401808-cd26-5103-b7f4-32602492563a)

Chapter Seventeen (#ub82ae9b2-71c9-5362-bb42-13c1b3e78333)

Chapter Eighteen (#u0cffd4af-593b-527f-8aa2-b68fd5caf422)

Chapter Nineteen (#uf9d2a741-a6e9-5a09-a84d-a52a214e4c44)

Chapter Twenty (#u28e37e3d-53a6-565d-98d2-6239df48b276)

Chapter Twenty-One (#ua137fe29-aaa4-55e6-8646-bf1ec3bf0546)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#ucaeddb4b-058d-5dc4-9da9-7960dfffd0df)

Acknowledgements (#u7fc3c6db-a527-574e-bb76-71e1bc503afa)

A Note From Anne (#u36014e39-2d09-51a5-87a1-49fff572ee56)

About the Author (#uf77266b7-607a-52aa-a703-363a9ba5997a)

Also by Anne Bennett (#u6f102201-58a5-553b-8eb9-362af74573e6)

About the Publisher (#ub039ac13-eed6-500e-8c3e-1fb06225f973)

ONE (#ua3d88705-3cbb-5370-877f-26d91e3d1aaa)

It was Norah Mulligan walking alongside her sister, Celia, who noticed Andy McCadden first. It was the first Saturday in March and the first Fair Day of 1920 in Donegal Town.

It was a fine day, but March living up to its name of coming in like a lion, meant it was blustery and cold enough for the girls to be glad they were so warmly clad. They were still wearing winter-weight dresses, Celia’s in muted red colours and Norah’s muted blue, and they were long enough to reach the top of their boots so the thick black stockings could not be seen. Over that they were wearing Donegal tweed shawls, fastened by Celtic Tara brooches, and their navy bonnets matched the woollen gloves that encased their hands.

Celia knew Norah considered bonnets old fashioned and babyish but Celia was glad of hers that day and also liked the blue ribbons that tied so securely under her chin. ‘Anyway,’ she had reasoned with her sister when she had complained again that day as she got ready in their room. ‘You’d have to have a hat of some sort – and just listen to the strength of that wind. Any other type of hat you had today would be tugged from your head in no time and in all likelihood go bowling down the road, however many hatpins you had stuck in it. You running to retrieve it would cause great entertainment to the rest of the town and I doubt that would please you much either.’

Norah said nothing to that because she did agree with Celia that bonnets were the safest option that day, especially when riding in the cart with their father where the wind was even more fierce. Given a choice she wouldn’t have gone out at all, but stayed inside by the fireside; however, their mother, Peggy, had given them a list of things to buy as they were going in on the cart with their father who had some beef calves for sale. They did go in often on Saturdays because the Mulligans’ farm was just outside the town and Peggy always said her gallivanting days were over, so the girls each had a bulging shopping bag as they crossed the square – shaped like a diamond and always referred to as such – to the Abbey Hotel where they were meeting their father.

The beasts for sale were in pens filling the Diamond and the pungent smell rose in the air and the noise of them, the bleating and grunting and lowing and squawking of the hens, just added to the general racket, for the streets were thronged with people, the shops doing a roaring trade.

As usual on a Fair Day the pubs were open all day. Some might have their doors slightly ajar so the two girls might get a tantalising glimpse inside. That was all they would get though, a glimpse, and if any men were standing outside with their pints, they would chivvy them on, for respectable women didn’t frequent pubs and certainly not young ladies like Norah and Celia.

The cluster of gypsies was there too as they were every Fair Day, standing slightly apart from the townsfolk. They’d always held a fascination for Celia, the black-haired, swarthy-skinned men who often had a jaunty manner and in the main wore different clothes to most men of Celia’s acquaintance: light-coloured cotton shirts, moleskin waistcoats and some, mainly the younger ones, bright knotted handkerchiefs tied at their necks, and they were not above giving girls a broad wink as they passed. The women seemed far more dowdy in comparison, for they were usually dressed in black or grey or dark brown with a craggy shawl around their shoulders and more often than not there was a baby wrapped up in it, while skinny, scantily dressed, barefoot children scampered around them.

Suddenly, Norah gave her sister a poke in the ribs, taking her mind from the gypsies as she said, ‘Will you look at the set of him,’ and she jerked her head to the collection of people at the edge of the fair at the Hireling Stall who were in search of someone to take them to work on one of the farms or as servants in the house. As the Mulligans needed no outside help, Celia had never taken much notice of them and she cast her eyes over them now. There were, however, a few young men and she said, ‘Which one?’

Norah cast her eyes upwards. ‘Heavens, Celia,’ she cried. ‘Do you really need to ask? The blond-haired one of course, the one smiling over at us this very moment.’

‘I’m sure you’re wrong, Norah,’ Celia said. ‘It can’t be us.’

‘Celia, he’s looking this way and smiling so he must be smiling at someone or something,’ Norah retorted. ‘No one but an idiot would stand there with a wide grin on his face for no reason and I tell you he is the least idiotic man that I’ve seen in a long time. Quite a looker in fact.’

Celia stole a look at the man in question and did think he was most striking-looking and she took in the fact that he was tall, broad-shouldered and well-muscled and the sun was shining on his back, making it seem like he had a halo around his mop of very blond hair. She couldn’t see the colour of his eyes, but she did see that they were twinkling so much it was like light that had been lit inside him and she felt herself smiling back. She looked away quickly and felt a crimson flush flood over her face. She saw that Norah had noticed her blush and, to prevent her teasing, said sharply, ‘Mammy will wash your mouth out with carbolic if she hears you talking this way.’

‘Better not tell her then,’ Norah said impishly.

‘I just might.’

‘No, you won’t,’ Norah said assuredly. ‘You’re no tell-tale.’

‘All right,’ Celia conceded. ‘You’re right, I’d never tell Mammy. But talking of men, I was wondering the other day about you wanting to go to America and all. Whatever are you going to do about Joseph O’Leary?’

‘What’s Joseph O’Leary to do with anything?’

‘You’re walking out with him.’

‘Hardly,’ Norah said. ‘We’ve just been out a few times.’

‘Huh, more than a few I’d say,’ Celia said. ‘But it doesn’t matter how long it’s been going on, in anyone’s book that constitutes walking out together.’

‘Well if you must know,’ Norah told her sister, ‘I’m using Joseph to practise on.’

‘Oh Norah, that’s a dreadful thing to do to someone,’ Celia cried, really shocked because she liked Joseph. He was a nice man and had an open honest face, a wide generous mouth and his fine head of wavy hair was as dark brown as his eyes, which were nearly always fastened on her sister.

Norah shrugged carelessly. ‘I had to know what it was like. I am preparing for when I go to America.’

‘Does he know your plans?’

‘Sort of,’ Norah said. ‘I mean, he knows I want to go.’

‘Does he know you’re really going, that Aunt Maria said she’ll sponsor you and pay your fare and everything?’

‘Well no,’ Norah admitted.

‘Poor Joseph,’ Celia said. ‘He’ll be heartbroken.’

‘Hearts don’t break that easy, Celia.’

‘Well I bet yours will if you can’t go to America after all and Mammy could stop you because she’s great friends with the O’Learys.’

‘Mammy will be able to do nothing,’ Norah said confidently. ‘She has made me wait until I’m twenty-one and that was bad enough, but I will be that in three months’ time and then I can please myself.’

‘She doesn’t want you to go.’

‘I know that and that was why she made me wait until I was twenty-one.’

‘And that doesn’t worry you?’

‘It would if I let it,’ Norah said. ‘Now you worry about everything and in fact you would worry yourself into an early grave if you had nothing to worry about. You never want to hurt people’s feelings either and, while it’s nice to be that way, it could stop you doing something you really want to do in case someone disapproves.’

‘Like you going to America?’

‘Exactly like that.’

‘But I’d never want to leave here,’ Celia said, looking around the town she loved so much. She loved everything, the rolling hills she could see from her bedroom window dotted with velvet-nosed cows calmly chewing the cud, or the sheep pulling relentlessly at the grass as if their lives depended upon it, and here and there squat cottages with plumes of grey smoke rising from the chimneys wafting in the air. Their farmhouse was no small cottage however for it was built of brick with a slate roof and unusually for Ireland then, it was two storeyed. Downstairs there was a well-fitted scullery with a tin bath hung on a hook behind the door and leading off it, a large kitchen with a range with a scrubbed wooden table beside it and an easy chair before the hearth. It was where the family spent most of their time, for though there was a separate sitting room it was seldom used. The stairs ran along the kitchen wall and upstairs were three sizeable bedrooms; her parents had their own room, another she shared with Norah and Ellie and the other one was for Tom, Dermot and Sammy.

It was all so dear to her, familiar and safe and she couldn’t see why anyone would want to leave it. She said this to Norah and added, ‘I’d never want to go away from here.’

‘Never is a long time,’ Norah said. ‘And you’re only seventeen. I felt like that at seventeen. But by the time I was twenty I felt as if I was suffocating with the sameness of every day.’

‘But don’t you want a husband and children?’

‘Not yet,’ Norah said emphatically. ‘Why would I? I intend to keep marriage and all it entails at bay or at least until I meet and fall madly in love with a tall and very handsome man, who has plenty of money and will adore me totally.’

Celia burst out laughing. ‘Shouldn’t say there’s many of them about.’

‘Not in Donegal certainly,’ Norah conceded. ‘But who knows what America holds? The country may be littered with them.’

Celia laughed. Oh, how she would miss her sister for, since leaving school, she saw her old friends rarely. She’d meet some of them occasionally in Donegal Town, but it wasn’t arranged or anything, they would just bump into one another. They seldom had time for any sort of lingering chats because all the girls would usually have a list of errands to do for their mothers. The only other time to meet was at Mass on Sunday but no one dawdled after that because most of the congregation had taken communion and so were ravenously hungry, for no one was allowed to eat or drink if they were taking communion. So the two sisters had relied on each other – and Peggy wasn’t the only one to hope that Norah would change her mind in the months till her twenty-first birthday.

Celia opened her mouth to say something to Norah about how much she would miss her, but there was no time because they had reached the Abbey Hotel and their father, Dan, was waiting on them. Celia thought her father a fairly handsome man for one of his age; his black curls had not a hint of grey and he had deep dark brown eyes just like her eldest brother, Tom. Only his nose let him down for it was slightly bulbous, but his mouth was a much better shape. Tom was just like a younger version of him. Dan was a jovial man too and as they approached his laugh rang out at something someone in the crowd had said and it was so infectious that Celia and Norah were smiling too as they reached him.

He had told them on the way in that if he sold the calves early enough, they could wait on and he’d take them home in the cart, but if the calves were not sold, he might stay on and they would have to make their own way home. Celia wondered why he even bothered saying that because she had never known her father come home early on a Fair Day and his delay had more to do with the pubs open all the day and old friends to chat to and gather news from than it had to do with selling the calves.

Norah knew that too, but both girls went on with the pretence. ‘Have you sold the calves, Daddy?’

Dan took a swig of Guinness from the pint glass he held before he said, ‘Might have. Man said he’d tell me this afternoon when his brother has a chance to look them over. So you must make your own way home. Tell your mother.’

‘Yes, Daddy,’ the girls chorused, though they knew their mother wouldn’t be the least bit surprised.

They passed the Hireling Stall again on their way out of town and Celia saw the blond-haired man talking to Dinny Fitzgerald whose farm abutted theirs in many places. ‘Looks like Dinny’s hiring that chap,’ Norah remarked.

‘Well Daddy said he would have to hire someone after his son upped and went to America,’ Celia said and added, ‘Huh, seems all the Irish farms are emptying of young men going to that brave New World.’

‘Yes and I might want to nab one of those men for myself in due course,’ Norah said. ‘That’s why I have to practise on poor Joseph.’ And her tinkling laugh rang out at the aghast look on Celia’s face.

It was some time later when Dan Mulligan came home, very loud and good-humoured, which Peggy said was the Guinness effect. He brought all the news from the town though, including the fact that Dinny Fitzgerald had indeed taken on a new farm hand.

‘Must be no sign of his son retuning then,’ remarked Peggy. ‘America seems a terrible lure to the young people.’

‘Aye,’ Dan said. ‘But sure it’s hard for a man when he has only the one son who will inherit the farm and who has so little interest in it he is away to pastures new, and so Dinny has to have strangers in to work it with him.’

‘Maybe the lad didn’t take to the life,’ Norah said. ‘You know, maybe he doesn’t want to be a farmer.’

‘Take to the life,’ Dan said with scorn. ‘What’s whether he likes it or not got to do with anything? People can’t always do as they please and in this case there is no one else and it’s his birthright. Is he not going to come back and take it on board after Dinny’s day, let the farm fall to strangers and after it being in the family generations? Tell you, I’d find that hard to take.’

‘Well not every man has the rake of sons you have,’ Peggy said. ‘So if our Tom here didn’t want it, then Dermot might or even wee Sammy, for all he’s only seven now. Or Jim might come back from America and take it on if there was no one else. Mulligans will farm here for some time to come I think.’

Celia, listening as she washed the dishes in the scullery, knew her mother was right. She knew too most farmers wanted more than one son but the eldest inherited everything and the others had to make their own way. That’s what Jim had said when he left for America’s shores. It had been five years ago when he had decided. He had been twenty-three then, two years younger than Tom and, knowing his future was in his own hands, he had written to Aunt Maria who had sailed away to New York many years before with her new American husband and was quite a wealthy woman now, but a childless one. She had been delighted to hear from Jim, and agreed to not only sponsor him but also pay his fare and said she would do the same for all who wanted to follow their brother.

Peggy hadn’t liked to hear that bit and she watched the restless Norah growing up rather anxiously and was glad and relieved when she settled with Joseph O’Leary, but not as settled as she might be, because just a few months before she had claimed it wasn’t serious between them. There was no understanding, Norah had said and it was just as well because she wanted to follow Jim to America.

‘If you throw Joseph over you’ll get your name up, girl,’ Mammy had said at the time.

Norah had not been a bit abashed. ‘Maybe here I might,’ was her retort. ‘In America they wouldn’t care a jot I bet. According to what Jim says, it’s much freer there and you don’t have to marry a man you go for a walk with.’

Peggy’s sigh was almost imperceptible for she knew another child was going to cross the Atlantic.

Celia too wished Norah would fall madly in love with Joseph O’Leary and declare she couldn’t bear to leave him, but she had to admit that didn’t look the slightest bit likely and she knew Norah was every day more determined than ever to sail to America. She had marked her twenty-first birthday on the calendar in the room they shared with a big red circle and each day she marked another day off. Thinking about it now as she swirled the dishes in the hot water Celia felt very depressed and wondered if one by one they would all go away.

Two years before, her sister Katie had married a Donegal man but he was a wheelwright and had a house and business in Greencastle in Inishowan, a fair distance from Donegal Town, and that’s where Katie lived now. So they hadn’t visited her since the wedding, not even when she had her first child that she named Brendan.

Maggie might have stayed and married a local man for she was the prettiest of them all and had a string of admirers. Mammy would shake her head over her and said she would be called fast and loose, as she would accept gifts pressed on her by men, without any sort of understanding between them. She was in no hurry to settle down, she said, but Maggie had taken sick with TB a year after Jim had left for America. To protect everyone else she had been taken to the sanatorium in Donegal Town and died six weeks later when she was nineteen years old.

That had been a sad time for them all, Celia remembered, and for herself too because she hadn’t really had to deal with death before and certainly not the death of one so young and pretty and full of the joys of life. It seemed like the whole town had turned out for her funeral, but afterwards the family had been left alone to deal with the loss of her.

Time was the great healer, everyone said, and Celia wondered about that because for a long time there had been an agonising pang in her heart if she allowed herself to think of Maggie. She imagined it was the same for her mother for, though Peggy had never spoken about it, Celia had seen the sadness in her hazel-coloured eyes and the lines pulling down her mouth were deeper than ever and there were more grey streaks in her light-brown hair. Eventually, though, time worked its magic and they each learned to cope in their own way for life had to go on.

‘Have you not finished washing those pots yet?’ Peggy called and her words jerked Celia from her reverie and she attended to the job in hand.

Monday morning they were expecting Fitzgerald to send over his bull to service the cows, for their father had told them the night before, but as the cart rumbled across the cobbles outside the cottage door, Celia, peering through the kitchen window, was surprised to see Fitzgerald’s hireling driving the cart pulling the horse box.

‘Why should you be so surprised?’ the man replied when Celia voiced this as she stepped into the yard to meet him. ‘I have been doing farm work all my life and driving a horse and cart is just part of it.’

‘I saw you at the fair on Saturday,’ Celia said.

‘And I saw you,’ the man said with a slight nod in her direction. ‘And I was interested enough to ask someone your name so I know you to be Celia Mulligan. And mine,’ he added before Celia had recovered from her surprise, ‘is Andy McCadden and I am very pleased to make your acquaintance.’

He stuck out his hand as he said this and Celia would have felt it churlish to refuse to take it but, as their hands touched, she felt a very disturbing tingle run up her arm. It made her blush a little and, when she looked up into his face and saw his sparkling eyes were vivid blue, she found herself smiling too as she said, ‘I’m very pleased to meet you, Mr McCadden.’

‘Oh Andy please,’ the man protested and he still held her hand. ‘And may I not call you Celia? After all, we are neighbours.’

Celia knew her father probably wouldn’t see it that way but her father was not there, so she said, ‘Yes I think that will be all right.’

There was a sudden bellow of protest from the bull and she said, ‘Now we’d better see to the bull? My father is in the top field separating the cows. I’ll show you if you get the bull out now.’

‘You’ll not be nervous?’ Andy said as he began unshackling the back that would drop down to form a ramp for the bull to walk down.

‘Not so long as you can control him,’ Celia said.

‘Oh I think so,’ Andy said. ‘Mind you,’ he said as they went out down the lane leading the bull by the ring on his nose, ‘I’m surprised you haven’t your own bull on a farm of this size.’

‘Oh we did have our own bull one time,’ Celia said. ‘It was long before I was born and my parents were not married that long and Mammy was expecting her first child. The bull pulled away from Daddy and charged at Mammy who had just stepped out into the yard. He gored her quite badly and she was taken to the hospital and there she lost the child she’d been carrying and nearly lost her own life too. Even after she recovered, the doctor thought she might be too damaged inside to carry another child. At least that has proven not to be the case, but she would never tolerate a bull around the place afterwards.’

‘Sorry about your mother and all,’ Andy said. ‘But I can’t help being pleased that you haven’t your own bull.’

‘Why on earth would that matter to you one way or the other?’ Celia asked in genuine surprise.

‘Because this way I get a chance to talk to you,’ Andy declared.

Celia blushed crimson. ‘Hush,’ she cautioned.

‘What?’ Andy said. ‘We are doing no harm talking.’ And then, seeing how uncomfortable Celia was, he went on, ‘Is it because I’m a hireling boy and you a farmer’s daughter?’

Celia’s silence gave Andy his answer and he said, ‘That’s hardly fair. My elder brother Christie will inherit our farm and after my father paid out for my two sisters’ weddings last year he said I had to make my own way in the world. He has a point because I am twenty-one now and there are two young ones at home for them to provide for and I would have to leave the farm eventually anyway.’

‘I know,’ Celia said. ‘That’s how it is for many. Tom will have the farm after Daddy’s day.’

‘Have you other brothers?’

‘The next eldest to him went to America where we have an aunt living.’

‘It’s handy to have a relative in America.’

‘It is if you want to go there, I suppose,’ Celia said.

‘You haven’t any hankering to follow him then?’

Celia shook her head vehemently. ‘Not me,’ she said. ‘My sister Norah is breaking her neck to go, but Mammy is making her wait until she’s twenty-one.’

‘And is that far away?’

Celia sighed. ‘Not far enough,’ she said. ‘It’s just a few months and I will so miss her when she’s gone.’

‘Have you no more brothers and sisters?’

‘Yes,’ Celia said. ‘Dermot is over three years younger than me, so he is nearly fifteen and left school now and then there is Ellie who is nine and Sammy who is the youngest at seven.’

‘Not much company for you then?’

Celia shook her head. ‘I’d say not,’ and then she added wryly, ‘Mind you, I might be too busy to get lonely for I will have to do Norah’s jobs as well as my own.’

‘You can’t work all the time,’ Andy said. ‘Do you never go to the dances and socials in the town?’

Celia shook her head.

‘Why on earth not?’

‘I don’t know why not,’ Celia admitted. ‘It’s just never come up, that’s all.’

‘Well maybe you should ask about it?’ Andy said. ‘No wonder your sister can’t wait to go to America if she is on the farm all the days of her life. There’s a dance this Saturday evening.’

‘And are you going to it?’

‘I am surely,’ Andy said. ‘Mr Fitzgerald told me about it himself. He advised me to go and meet some of the townsfolk and it couldn’t be more respectable, for its run by the church and I’m sure the priest will be in attendance.’

Celia knew Father Casey would have a hand in anything the Catholic Church was involved in – particularly if it was something to do with young people, who he seemed to think were true limbs of Satan, judging by his sermons. And yet, despite the priest’s presence there, she had a sudden yen to go, for at nearly eighteen she was well old enough and she wondered why Norah had said nothing about it. Tom attended the dances but she never went out in the evening and neither did Norah, not even to a neighbour’s house for a rambling night, which was often an impromptu meeting, spread by word of mouth. There would be a lot of singing or the men would catch hold of the instruments they had brought and play the lilting music they had all grown up with and the women would roll up the rag rugs and step dance on the stone-flagged floor. She had never been to one, but before Maggie died the Mulligans had had rambling nights of their own and she remembered going to sleep with the tantalising music running round in her head. She didn’t say any of this to Andy for she had spied her father making his way towards them across the field and saw him quicken his pace when he saw his daughter in such earnest conversation with the hireling boy.

So Dan gave Andy a curt nod of the head as a greeting and said, ‘Bring him through into the field.’ And as Andy led the bull through the gate Dan said to Celia, ‘You go straight back to the house. This is no place for you anyway.’ And Celia turned and without even looking at Andy she returned to the farmhouse, deep in thought.

TWO (#ua3d88705-3cbb-5370-877f-26d91e3d1aaa)

‘Why do we never go to the socials or the dances in the town?’ Celia said as she and Norah washed up together in the scullery.

Norah shrugged. ‘What’s brought this on?’

‘Just wondered, that’s all,’ Celia said. ‘Heard a couple of girls talking about it in the town Saturday.’

‘Did you?’ Norah said in surprise. ‘I never heard anyone say anything and I’d have said we were together all the time.’ Her eyes narrowed suddenly and she said, ‘It wasn’t that hireling boy put you up to asking?’

‘He has got a name, that hireling boy,’ Celia said, irritated with Norah’s attitude. ‘He’s called Andy McCadden and he didn’t put me up to anything. He asked if I was going to the dance and I said, no, that we never go.’

‘What was it to him?’

‘God, Norah, he meant nothing I shouldn’t think,’ Celia said. ‘Just making conversation.’

‘Well you were doing your fair share of that,’ Norah said. ‘I watched you through the window, chatting together ten to the dozen. Very cosy it looked.’

‘What was I supposed to do, ignore him?’ Celia asked. ‘I was taking him to find Daddy and he was leading a bull by the nose. Not exactly some sort of romantic tryst. Anyway, why don’t we ever go to the dances and the odd social?’

‘Well Mammy would have thought you too young until just about now anyway.’

‘All right,’ Celia conceded. ‘But what about you? You’re nearly twenty-one.’

‘I know,’ Norah said and added with a slight sigh, ‘I went with Maggie a few times; maybe you were too young to remember it. When she took sick and then died I had no desire to go anywhere for some time and then we were in mourning for a year and so I sort of got out of the way of it and anyway I didn’t really want to go on my own.’

‘Tom goes.’

‘He’s a man and not much in the way of company,’ Norah said. ‘Anyway he’d hardly want me hanging on to his coat tails. After all he went there hunting for a wife.’

‘Golly!’ Celia exclaimed. ‘Did he really?’

‘Course he did,’ Norah said assuredly. ‘No frail-looking beauty for him, for he was on the lookout for some burly farmer’s daughter, with wide hips who can bear him a host of sons and still have the energy to roll up her sleeves and help him on the farm.’

Celia laughed softly. ‘Well he hasn’t, has he?’ she said. ‘Though no one said a word about it, everyone knows he’s courting Sinead McClusky and she is pretty and not the least bit burly.’

‘Maybe not but you couldn’t describe her as delicate either and she is a farmer’s daughter.’

‘What about love?’

‘You’re such a child yet,’ Norah said disparagingly. ‘What does Mammy say? “Love flies out of the window when the bills come in the door.” Tom will do his duty, as you probably will too in time.’

‘Me?’ Celia’s voice came out in a shriek of surprise.

‘Ssh,’ Norah cautioned. ‘Look, Celia, it’s best you know for this is how it is. If I stayed here and threw Joseph over, apart from the fact my name would be mud, Daddy might feel it in my best interests to get me hooked up with someone else and of his choosing. This might well happen to you and it isn’t always in our best interests either, but it’s done to increase the land he has or something of that nature. And it will be no good claiming you don’t love the man they’re chaining you to for life, because that won’t matter at all.’

‘What about Mammy?’ Celia cried, her voice rising high in indignation. ‘Surely she wouldn’t agree to my marrying a man I didn’t love?’

Norah shrugged. ‘Possibly the same thing happened to her and it’s more than likely she sees no harm in it.’

‘Well I see plenty of harm in it,’ Celia said. ‘You said something like this before, but this has decided me. I shall not marry unless for love and no one can make me marry someone I don’t want.’

‘Daddy might make your life difficult.’

Celia shrugged. ‘I can cope with that if I have to.’

‘Well to find someone to take your fancy,’ Norah said, ‘you need to go out and have a look at what is on offer, for I doubt hosts of boys and young men will be beating a path to our door. And so I think we should put it to Mammy and Daddy that we start going out more and the dance this Saturday is as good a way to start as any. You just make sure you don’t lose your heart to a hireling man.’

Celia expected some opposition to her and Norah going to the dance that Saturday evening when Norah broached it at the dinner table the following day, but there wasn’t much. Peggy in fact was all for it.

‘Isn’t Celia a mite young for that sort of carry-on?’ Dan muttered.

Celia suppressed a sigh as her mother said, ‘She is young, I grant you, but Tom will be there and he can take them down and bring them back and be on hand to disperse any undesirable man who might be making a nuisance of himself.’

‘And I will be there to see no harm befalls Celia,’ Norah said. ‘It isn’t as if I’m new to the dances – I used to go along with Maggie.’

Peggy sighed. ‘Ah yes, you did indeed, child,’ she said, a mite sadly. She had no desire to prevent them from going dancing, particularly Norah, for if she wasn’t going to marry Joseph maybe she should see if another Donegal man might catch her heart and then she might put the whole idea of America out of her head.

And so with permission given, the girls excitedly got ready for the dance on Saturday. They had no dance dresses as such but they had prettier dresses they kept for Mass. They were almost matching for each had a black bodice and full sleeves. Celia’s velvet skirt was dark red, Norah’s was midnight blue. Celia had loved her dress when Mammy had given it to her newly made by the talented dress maker and now she spun around in front of the mirror in an agony of excitement at going to her first dance.

‘Aren’t they pretty dresses?’ Celia cried.

‘They are pretty enough I grant you,’ Norah said. ‘It’s just that they are so long.’

‘Long?’

‘Yes, it’s so old fashioned now to have them this long. It is 1920 after all.’

‘Let me guess?’ Celia said. ‘I bet they’re not this length in America.’

‘No they aren’t,’ Norah said. ‘Men over there don’t swoon in shock when they get a glimpse of a woman’s ankle.’

‘How do you know?’ Celia demanded. ‘That’s not the sort of thing Jim would notice and he certainly wouldn’t bother to write and tell you.’

‘No he didn’t,’ Norah admitted. ‘But Aunt Maria did. And she said that the women wear pretty button boots, not the clod-hopping boots we have.’

‘Well pretty button boots would probably be little good in the farmyard,’ Celia pointed out. ‘And really we should be grateful for any boots at all when many around us are forced to go about barefoot.’

‘I suppose,’ Norah said with a sigh. ‘Anyway we can do nothing about either, so we’ll have to put up with it. Now don’t forget when you wash your hair to give it a final rinse with the rainwater in the water butt to give it extra shine.’

‘I know and then you’re putting it up for me.’

‘Yes and you won’t know yourself then.’

Norah knew Celia had no idea just how pretty she was with her auburn locks, high cheekbones, flawless complexion, large deep brown eyes and a mouth like a perfect rosebud. She knew her sister would be a stunner when she was fully mature. She herself looked pretty enough, although her hair was a mediocre brown and her eyes, while large enough, were more of a hazel colour.

She sighed for she wished her mother would let her buy some powder so she could cover the freckles that the spring sunshine was bringing out in full bloom on the bridge of her nose and under her eyes. However, she had heard her mother say just the other day that women who used cosmetics were fast and no better than they should be.

She imagined things would be different in America, but she wasn’t there yet and Celia, catching sight of Norah’s forlorn face, cried, ‘Why on earth are you frowning so?’

Norah shrugged and said, ‘It’s nothing. Come on, Tom will be waiting on us and you know how he hates hanging about.’

Celia did. Her brother wasn’t known for his patience so she scurried along after her sister.

The church hall was a familiar place to Celia and she passed the priest lurking in the porch watching all the people arriving. She greeted him as she passed and went into the hall, where her mouth dropped open with astonishment for she had never seen it set up for a dance before, with the musicians tuning up on the stage and the tables and chairs positioned around the edges of the room while still leaving enough room in there for the bar where the men were clustered around having their pints pulled, Tom amongst them. Celia knew respectable women and certainly girls didn’t go near bars though. Tom would bring them a soft drink over and Norah said that was that as far as he was concerned.

‘If you want another we shall have to go and find him,’ Norah said.

‘What d’you do if you haven’t come with a man?’ Celia asked.

Norah shrugged. ‘If you haven’t got a handy brother or male cousin it’s often safer to stay at home,’ she said.

‘Safer?’

‘Yes,’ Norah affirmed. ‘Some men are the very devil when they have a drink on them.’ And then glancing at the door she said, ‘Oh Lord. Here’s Joseph come in the door and looks very surprised to see me, as well he might be.’

Celia turned and saw Joseph’s eyes widen in surprise at seeing Norah, yet Celia saw that he was anything but displeased about it because his face was lit up in a smile of welcome. ‘I expect I will have to go and be pleasant to him,’ Norah said.

‘I’d say so,’ Celia said. ‘Look at that smile and it’s all for you. I’d say he’s really gone on you.’

‘Yes,’ Norah said. ‘I wish he wasn’t.’

‘Well he can’t help how he feels, can he?’ Celia said. ‘And anyway it’s partly your fault. You should have been straight with him about your intention to emigrate to America from the start.’

Celia saw from the reddening on Norah’s cheeks that what she had said had hit home and watched her walk across towards Joseph. Celia turned away, wondering what it would feel like to have a man smile just for her in such a way.

And then she saw Andy McCadden at the bar smiling at her in much the same way. It made her feel slightly light-headed and before she was able to recover her senses Andy was by her side and saying, ‘I thought you said you never came to the dances, Miss Celia Mulligan.’

Before answering him, Celia took a surreptitious look around. Tom, she saw, was talking to Sinead McClusky and Norah was away talking to Joseph and so she faced Andy and said, ‘We don’t. This is the first one I have been to and I wasn’t sure I would be let go and it was only because Norah was here to keep an eye on me and my brother was walking us down and back again that made Mammy say I could go.’

‘And where are your protectors now?’ Andy asked in a bantering tone. ‘Not doing their job very well, I would say. Leaving you stranded in the middle of the room without even a drink in your hand. I can remedy that at least.’

‘Oh no,’ Celia cried. ‘Really it’s all right.’

‘It’s not all right,’ Andy said. ‘I have a great thirst on me, which I intend to slake with a pint and I can hardly drink alone. I’m afraid I must insist you join with me.’

And before Celia was able to make any sort of reply to this, Andy wheeled away and left her standing there. She felt rather self-conscious and looked round to see if she could see Tom or Norah, thinking that she might have joined them, but so many people were now in the hall she couldn’t see them. And then Andy was back with a glass of Guinness in one hand and a glass of slightly cloudy liquid in the other which he held out to Celia. She didn’t take it though and, eyeing it suspiciously, said, ‘What is it?’

‘Homemade apple juice.’

‘You mean cider?’

‘No. If I meant cider I would have said cider,’ Andy said with a smile. ‘I would never offer anyone of your tender years alcohol. This is what I said it was, apple juice plain and simple, and it will do you no harm whatsoever. Take it.’

Celia had barely taken the glass from him when Norah pounced on her. She had felt guilty for leaving her to her own devices to talk to Joseph and hadn’t meant to be away so long. Now she said sharply, ‘What are you up to and what is that in that glass?’

‘I’m not up to anything,’ Celia retorted. ‘Why should you think I was? And all that’s in my glass is apple juice.’

Norah was still looking at it suspiciously and Andy put in, ‘It’s true what Miss Mulligan said. I found her looking a bit lost. I believe it is her first time at an event like this.’

Norah knew it was and that was the very reason she shouldn’t have left her high and dry as she had and so when Andy went on, ‘I was buying a drink for myself and so I offered to buy one for your sister and it is, as she said, apple juice,’ Norah couldn’t say anything but, ‘Thank you for looking after her so well, Mr …’

‘McCadden,’ Andy said, extending his hand. ‘Andy McCadden.’

‘Norah Mulligan,’ Norah felt obliged to say as she took hold of the man’s proffered hand. ‘And you have already met my sister, Celia.’

‘Yes indeed.’

‘And now you must excuse us,’ Norah said. ‘There are some people I want Celia to meet.’

Andy gave a sardonic smile as if he didn’t believe for one moment that there were people Celia had to meet but he said, ‘Of course.’ And then, as they turned away, he added, ‘Perhaps I can claim you both for a dance later?’

Celia didn’t answer for she had seen Norah’s lips purse in annoyance and then Norah answered in clipped tones, ‘We’ll have to see, Mr McCadden. I can make you no promises.’

‘There was no need to be rude to Mr McCadden,’ Celia hissed through the side of her mouth to her sister as soon as she was sure they were out of earshot of the man who was standing watching them walk across the room.

‘I wasn’t at all rude,’ Norah protested. ‘I was perfectly polite.’

‘You were stiff and awkward, like,’ Celia persisted. ‘And it wasn’t as if he did anything wrong – unless talking to me and buying me a drink is wrong. I did look round for you and Tom and couldn’t see either of you.’

‘I can’t answer for Tom, but I stepped outside with Joseph,’ Norah said. ‘After what you said, I decided to tell him once and for all about America. I thought I had strung him along enough and he deserved that I tell him the truth. He was a bit upset, wouldn’t accept it you know, so I stayed talking to him longer than I intended. I did think Tom might have checked to see you were all right and though I think Mr McCadden was pleasant enough he is not the kind of person that you should encourage. And now here’s Tom coming with a drink for each of us. Put the one McCadden brought you on the table quick before he sees it.’

‘Why? It’s only a drink, Norah.’

‘Will you do as I tell you,’ Norah hissed. ‘There are things that are not done and accepting a drink from a man unrelated to you and almost a stranger to boot is one of them. You are going the right way to make Tom tear him off in no uncertain terms for being familiar and Tom won’t care how rude he is.’

Celia thought Norah was probably right and so she slipped the drink Andy had brought her onto the table beside her just as Tom came into view, smiling jovially at the two girls. ‘Enjoying yourselves?’ he asked.

‘We’ve only just got here,’ Norah pointed out, but Celia said, ‘I think it’s quite exciting. It’s nothing like the church hall is normally.’

‘No indeed it isn’t,’ Tom said as the band struck up the music for a four-hand reel. He asked, ‘Now will you be all right? I promised Sinead a dance.’

‘Then go on,’ Norah said. ‘There are lots of people I want to introduce Celia to.’

Tom left them as Norah slipped her arm through Celia’s. ‘Come on,’ she said. ‘There really are lots of people I want you to meet, men as well as girls, and I think I can guarantee that, looking as you do, you will be up dancing most of the night and won’t give a thought to Mr McCadden.’

In a way Norah was right for Celia proved a very popular girl. She was slight in build, the sort of girl that the men she was introduced to wanted to protect, and so light on her feet as she danced the set dances and jigs and reels and polkas that she loved. Not even Father Casey looking about him with disapproval could quell Celia’s enjoyment. And yet she couldn’t get Andy McCadden quite out of her mind and every time she caught sight of him his brooding eyes seemed to be constantly fastened on her.

They lined up for the two-handed reel and Andy suddenly left the bar and joined the line with another woman. It was the sort of dance when the girls started with one partner but danced with different men in the set until they ended up back with their original partner and so at one point Celia was facing Andy. As they moved to the centre Andy spoke quietly through the side of his mouth, ‘Your sister is trying to keep us apart.’ Celia didn’t answer – there wasn’t time anyway – and the second time they came near to one another he said, ‘D’you ever walk out on Sunday afternoons?’ and the third and last time they came close he said, ‘We could meet and chat.’

Before Celia had time to digest what Andy had said, never mind reply to it, she was facing another partner and the dance went on and she was glad that she knew the dance so well and didn’t have to think much about it because her head was in a whirl with the words Andy had whispered to her. As the dance drew to a close and she thanked the man who had partnered her, she had to own that Andy was right about one thing: Norah had taken a distinct dislike to Andy McCadden and was going to do her level best to keep them apart. Celia thought she had a nerve. Norah was prepared to swan off to America, upsetting everyone to follow her dream, and she had told Celia she was too fond of trying to please people and she had to stop that and look to her own future. Now Celia wasn’t sure that Andy McCadden would be part of that future, she was a tad young to see that far ahead, but what was wrong with just being friends or, at the very least, being civil to one another? Norah didn’t have to treat him as if he had leprosy.

She was sitting at a table alone for once, a little tired from all the dancing, and she scanned the room for Tom and Norah, just in time to see Tom leading Sinead outside. Norah was nowhere to be seen and suddenly Andy was by her side again with another glass of apple juice in his hand.

‘Thank you,’ she said as she took it from him without the slightest hesitation and drank it gratefully.

‘You look as if you were in need of that,’ Andy said as he sat on the seat beside her.

‘I was thirsty,’ Celia admitted. ‘It’s all the dancing.’

‘And tired, I’ll warrant.’

‘Yes a little.’

‘That’s a pity.’

‘Why?’

‘They are playing the last waltz,’ Andy said. ‘I was going to ask you to dance with me but if you are tired …’

Celia hesitated, for she knew the last waltz was special and she shouldn’t dance it with a man she hardly knew. Andy saw her hesitation and said, ‘Or perhaps you think your brother and sister would not approve.’

Andy wasn’t to know, but his words lit a little light of rebellion in Celia’s heart. What right had Norah and Tom to judge her? All she was proposing to do was dance with a man she had spoken to a few times in open view of everyone. It wasn’t as if she was sneaking outside like Tom with Sinead, who might well be up to more than just holding hands, and she had no idea where Norah was. And so she smiled at Andy and, at the radiance of that smile, Andy felt a lurch in his stomach as if he’d been kicked by a mule.

‘I’m not that tired, Andy, and I would love to dance with you,’ Celia said.

She stood up and Andy took her by the hand and she glided into his arms. As he tightened them around her she felt a slight tremor that began in her toes run all through her body. Andy felt it too and it aroused his protective instincts and he held her even tighter. ‘You’re shivering. Are you afraid?’

‘No,’ Celia answered, ‘I’ve never been less afraid than I am at this minute. I don’t know why I’m trembling so much, but it isn’t unpleasant.’

‘Oh that’s all right then,’ Andy said with a throaty chuckle and swept Celia across the floor with a flourish and that’s what Norah saw as she came back into the hall.

Had Norah heard the conversation between Celia and Andy McCadden she would have been further upset because, as she re-entered the hall, Celia was looking at Andy as if he had taken leave of his senses as she said, ‘I can’t just take off like that on a Sunday afternoon.’

‘Why not?’

‘It would be thought odd,’ she said. ‘It’s not something I ever do.’

‘Don’t see why not,’ Andy persisted. ‘It’s a normal thing to do, to go for a walk on a Sunday afternoon. What do you usually do?’

That was the rub, Celia thought, for she normally did nothing; that is, she worked harder than any other day in the week and so did Norah and their mother, for from the minute they returned from Mass, light-headed with hunger, they would be cooking up a big breakfast and barely had they eaten that and cleared away than they started on the dinner. The washing-up after that Sunday dinner seemed to take forever and while Celia and Norah tackled that Peggy would make some delicacies and pasties to be served after tea.

Then sometimes Norah would take up the embroidery she was so fond of. The young ones would be playing outside, Dermot would be going to meet with other young fellows in the town like himself, Tom off to see Sinead, and her parents would doze in front of the fire. Celia loved to read but all she was allowed to read on Sunday was the Holy Bible and she thought it the dullest day in the week and suddenly going for a walk seemed a very attractive prospect.

And yet she hesitated, for she knew however bored she was on Sunday, walking out on the hills with a man would not be viewed as a viable alternative. ‘I don’t know you,’ she said at last.

‘You do,’ Andy insisted. ‘I am Andy McCadden, second son of Francie McCadden and trying to make his way in the world.’

‘That’s not it,’ Celia said. ‘I mean, I know who you are but that is not the same as knowing a person.’

‘Well wouldn’t we get to know each other better if we walked and talked?’ Andy said. ‘Isn’t that what it’s all about?’

‘Mm, I suppose,’ Celia conceded and then shook her head. ‘I wouldn’t be let.’

‘Well that’s a real shame,’ Andy said as the waltz drew to a close and he continued to hold Celia as he went on, ‘I would say bring your sister but she seems to hate my guts – she’s looking daggers at us now.’

Andy was right. Celia glanced across at Norah and saw her eyes smouldering in temper. She felt her stomach give a lurch for she knew she was for the high jump and then, as Norah gave a sharp jerk of her head, she said, ‘I’ll have to go.’

‘All right,’ Andy said. ‘But if you are ever allowed to make your own mind up about things, I shall be walking around Lough Eske tomorrow afternoon if the weather is middling. Dinny and his wife tell me it’s a beautiful place to walk.’

As Celia trailed back towards her sister, she thought it probably was but she had never seen it herself, even though it was only a few miles away. They never walked just for the sake of walking, they walked only to get somewhere and she had never had an occasion to visit Lough Eske.

They had barely left the church hall before Norah started on Celia, saying she had made a holy show of herself dancing the last waltz with the hireling man and it was the first and last time she would take her to the dance if she was going to get up to that sort of carry-on.

Celia was really angry with her sister, but was unable to answer her because Tom had joined them and they both knew better than to involve him. He appeared not to notice any constraint between his sisters and was in high spirits himself. He asked Celia what she had thought of her first dance.

Celia ignored the glare Norah was casting her way and answered that she had thoroughly enjoyed herself. ‘Well I would have thought you would,’ Tom said. ‘I saw you up dancing a number of times.’

Celia glanced at her brother but he still had a smile on his face and the words weren’t spoken in any kind of a pointed way and so she relaxed and they fell to discussing the dance as they walked home together.

It was as they got in the house that Celia realised how weary she was. Her parents were already in bed and Tom, mindful of the milking in the morning, went straight to bed himself. Though Celia had intended to say something to Norah when they reached the semi-privacy of their bedroom, she fell asleep as soon as her head touched the pillow.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/anne-bennett/another-man-s-child/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Anne Bennett

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.17 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A moving family drama of one young woman’s fight to survive, to find her long-lost relatives and to find a place to call homeCelia Mulligan is in love with farm hand Andy McCadden, but when Andy asks her to marry him and she accepts, her father is furious – no daughter of his will marry a mere hireling. Celia elopes with Andy and they make their way by ship to England. While on board, Celia meets a demure young woman called Annabel who tells her in confidence that a friend of her father forced himself upon her and she has since fallen pregnant.Annabel plans to throw herself on her brother’s mercy and asks Celia if she will accompany her to Birmingham as her ladies maid. Without a job and with nothing to offer her, Andy encourages Celia to accept – he can find employment for himself and save for their future. But neither of them can foresee the events that will follow, and soon Celia will be forced to choose between the man she loves, and the love of a vulnerable child…