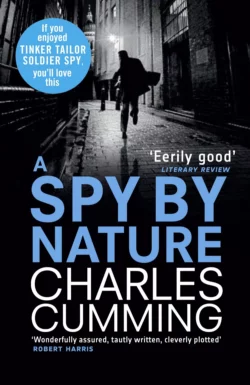

A Spy by Nature

Charles Cumming

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 813.25 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: For all fans of TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY comes this masterclass in suspense about a spy caught up in his own web of deception…Alec Milius is young, smart and ambitious – with a talent for deception. When a chance encounter opens the door to a career with MI6, he is desperate to make his mark.But life as a spy begins to take a terrible toll on himself and those around him, and soon Alec is chasing not just success but survival. Forced to work alone, he spins a web of deceit that traps him centre stage in a game of global espionage.In this new job, the difference between truth and a lie can be a matter of life and death. And for Alec, it’s getting harder to tell them apart…A Spy By Nature is the bestselling novel with which Charles Cumming announced his arrival as heir apparent to masters like John le Carré and Len Deighton; compellingly told, utterly authentic and heart-racingly intense, it will grip you till the very last page.