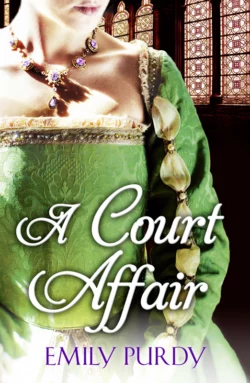

A Court Affair

Emily Purdy

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Uncovering the love triangle between Queen Elizabeth I, Robert Dudley, and his wife Amy, and her mysterious death,A Court Affair is an unforgettable story of ambition, lust and jealousy.Accused of conspiring with rebels to steal the throne, Princess Elizabeth is confined to the Tower of London by her half-sister, Queen Mary. There she finds solace in the arms of fellow prisoner – her childhood friend, Robert Dudley. But with Elizabeth’s ascension to the crown, Robert returns to his wife and the unhappy union he believes cheated him of his destiny to be king.As Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth knows the cruelty of marriage and roundly rejects her many suitors – with the exception of the power-hungry Robert. But their relationship carries a risk that could shake the very foundations of the House of Tudor. . .A Court Affair is a fascinating portrait of both the rise of Elizabeth I and one of the most compelling periods in history.