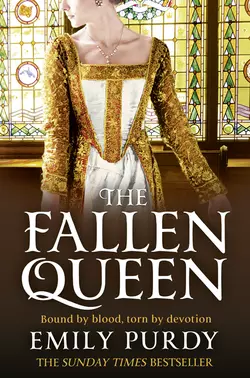

The Fallen Queen

Emily Purdy

Tyrannised by Bloody Mary and the Virgin Queen, Ladies Jane, Katherine and Mary Grey feared love was unthinkable.A gripping and bittersweet tale of broken families and broken hearts, courage and conviction, The Fallen Queen recounts an astonishing chapter in the hard-won battle for the Tudor throne.Led by love into the jaws of fate….Lady Jane Grey is crowned Queen at the behest of Edward VI. Her reign lasts only nine days before she is executed for treason.Lady Jane’s two sisters, Katherine and Mary, live on into Elizabeth I’s reign but in family misfortune they are bound, inspiring the Queen’s wrath against them.In secret, Katherine and Mary risk everything and disobey the royal order by marrying the men they love. Will their treachery be discovered? And must they face imprisonment in the Tower of London, just as their sister did before them?A stunning tale of treachery and treason, The Fallen Queen gives an unforgettable voice to three extraordinary sisters at the heart of a devastating conflict. Perfect for fans of The Tudors and Philippa Gregory’s The White Queen.

The Fallen Queen

EMILY PURDY

My God, why hast Thou forsaken me?

—Matthew 27:46

If you are not too long, I will wait here for you all my life.

—Oscar Wilde

While I Lived, Yours.

—The inscription engraved inside the ring Katherine Grey sent her husband from her deathbed

Table of Contents

Cover (#u3f2b6b85-8443-574c-acce-ab4d95a47380)

Title Page (#u64253d66-5b34-57d3-9a48-351052db7b58)

Epigraph (#ubb852b77-c625-51e8-8eab-be3ce97aa588)

Prologue (#ue6541519-4d4a-55f3-b0ef-898c208a212c)

Chapter 1 (#u6e97fb2c-fd54-58f0-bd2f-b8d3f3ce322b)

Chapter 2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript (#litres_trial_promo)

Further Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Questions for Discussion (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Books by Emily Purdy (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_5c2b9b90-ccc9-5598-89e8-f218793d78b2)

Lady Mary Grey (#ulink_5c2b9b90-ccc9-5598-89e8-f218793d78b2)

October 31, 1577

A small house in the parish of

St. Botolph’s-Without-Aldgate, London

What a splendid study in contradictions I am! Inside as well as out. A grown woman, wizened and white-haired, old before her time, trapped in a stunted, child-sized body, with a soul dark and stormy lit by flashes of brilliance, just like the sodden black velvet night outside my window, where the lightning flits, flashes, and flies, like a swift silver needle over the sky’s dark bodice, there again, then gone, in and out under a fluttering veil of frosty rain, and the thunder rumbles, grumbles, and booms just like a master tailor bellowing at his seamstresses to sew faster,faster, the gown must be finished in time. Though sage sits burning in a copper bowl upon my windowsill, an old custom to keep the ghosts away upon this night when the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead is said to shimmer gossamer-thin, moth-eaten and frayed with holes and gaps through which any spirit might seep or creep, and all the sane and sensible folk of London have shuttered their windows tight, I alone amongst my neighbours have boldly thrown the casements wide in welcome to all those I have loved and lost. The sage says, “Stay away!” but the open windows, like my heart, cry out, “Come in!” My mind conjures up a picture of Kate lovingly, indulgently, laughing at me, coppery ringlets shimmering and bobbing as she shakes her head, the stormy blue jewels of her eyes sparkling with glee, an amused smile traipsing merrily across her pink lips like a troupe of happy-go-lucky strolling players, as she bends to kiss my cheek and hug me tight, and, with mirth and a pinch of exasperation, in mock seriousness teasingly intones, “Mary, Mary, so contrary!” I can still smell her cinnamon rose perfume, as strong as if she were still holding me. And oh how I wish she were! I miss my pert, vivacious sister, so saucy and sweet, a lovely, lively girl; a contradiction herself like a cream-filled pastry with a spicy red pepper hidden inside, a girl with a song always in her heart who danced through life as though she wore a pair of enchanted slippers … before love weighed her down and made her so terribly sad that in the end she died of it.

Tears fill my eyes at this vivid vision of Kate, so real, achingly real, I can almost reach out and touch her, yet—another contradiction!—it almost makes me want to laugh, to throw back my head and cackle like a madwoman at my old, foolish self. And why should I not? After the life I’ve led, the sights I’ve seen, the secrets I’ve kept, the dangerous confidences that have been whispered into my ears, and the love I’ve had wrenched right out of my arms, consigned to the grave with my heart thudding down after like an anchor landing on the coffin lid, the memories that keep me wide awake in my bed at night, I think I’ve earned the right to squat down on my haunches and howl at the moon and give my neighbours cause to call me “Mad Mary” instead of “Crouchback Mary,” “Crook-Spine Mary,” “Devil-Damned and Twisted Mary,” “Milady Gargoyle,” or “The Goblin Lady.” A mind, and heart, can only take so much, and once broken, nothing is ever as strong as it was before; the mended seams are always vulnerable and weak. And it doesn’t really matter what they call me; I’ve heard all the names before. I’ve been hearing them since I was old enough to understand words.

The nursery maids spoke of me in fearful whispers as “the changeling” and “the goblin child,” and speculated that God had sent me to curse the Greys for their overweening pride and grandiose ambitions. But none of that matters now; I learned early that I had to be practical and discreet in order to survive, that I would only waste my life if I spent it weeping for what could never be, and that even though the darkness of the shadows may be frightening, sometimes it’s safer there, especially for someone little and strange like me.

By now I’ve become accustomed and numb, or at least indifferent, to it all. I cannot even imagine my life without the whispers, stares, gasps of horror, laughter, jests, and insults, fast-turned backs and swiveled heads, and pointing fingers, and the children who run alongside me and mock my wobble-waddle walk. The threats that if they don’t obey their parents and eat their porridge, learn their hornbook, clean their teeth, or say their prayers at night they will grow up to look like me has rendered many an unruly child the model of docility and impeccable obedience. And I’ve heard the stories describing how, whilst carrying me, my mother was frightened by a monkey that climbed in through her open window as she lay sleeping one stormy night and burrowed beneath her bedclothes for warmth, and when she turned in her sleep, inadvertently startling the little beast, it bit her; some stories even crudely name the privy part into which it sank its teeth, prematurely bringing on her protracted and hellish labour and my deformity.

Of course it isn’t true, as anyone who ever knew my lady-mother can readily attest. If a monkey had ever dared such a presumption, Frances Grey would have sat up and dealt him such a slap his eyes would have been forever crossed and he would have flown clear across the room and smashed into the wall and probably left half his brains there. But it makes a good story, and that’s what people like. And mayhap I should be flattered; such stories are like little gifts of immortality, truth or lies; as long as the tales are told, the people they are about never really die. Though ’tis sad to be remembered as a figure of fun or fright, one of Mother Nature’s mistakes.

Stubby, lumpy, and crooked, I stand no taller than a child of five, the age at which I stopped growing. Mangled but alive, I endure a life of pain, with a hunched and twisted spine that pushes my right shoulder higher than the left, a constant grinding ache in my back, hips, and knees, as though each joint possesses a full mouth of blackened, rotten teeth, and the limp seems to worsen every year. If I were to lift my skirts and roll down my stockings, I would see the veins bulging from my aching legs like a swarm of blue and purple snakes, swollen and pulsing with pain that I must take a syrup of poppies to subdue. Now I walk with a cane, a regal little staff crowned with a luminous orb of moonstone my husband made for me, knowing I would someday have need of it when he might not be there to carry me. Though it wasn’t always so. I used to be right sprightly in my youth and even danced on my wedding night.

It seems a century ago, though only a dozen years have actually passed since I, his “bumblebee bride,” as my Thomas, my Mr. Keyes, fondly called his Mrs. Keyes, lifted the black and yellow striped skirt of my wedding gown to display my dancing feet, nimble and proud in their dainty golden slippers, and the black silk stockings I had embroidered with a flight of dainty bees rising from my ankles to my knees, and—for my good husband’s eyes alone—raised my hems even higher to most brazenly reveal the sunny yellow satin bows of my garters. How he smiled and clapped delightedly as I danced a rollicking jig and the jolly pipers played. I kicked my limbs ever higher until I fell laughing on my bottom, well cushioned by taffeta and velvet and the padded bum roll tied around my hips underneath my petticoats. Then my Thomas paid the pipers and sent them on their way and lay down with me. That night when his lips followed the crooked path of my spine, going over and down the hump like taking a slow, meandering stroll down a hill, and he said it was like a perpetual question mark, an eternally beautiful mystery, and dotted it with a kiss on my sharply protruding tailbone, I stopped hating and cursing my malformed back. From that moment on whenever anyone made reference to it, whether in pity, malice, a mean spirit, or just a plain statement of fact, I always remembered his words, his lips tracing the question mark of my spine, and how very much he loved me. In his arms I discovered that ugliness is not always a curse. I knew I was well and truly loved only for myself, for the me inside my head and heart. If I had been a great beauty like Kate, I might have spent my whole life wondering if it was only my appearance that roused and stirred lust and tender regards in men’s loins and hearts.

In truth, though one would never know it to look at me, I am not, as years are measured, a very old woman. Yet I feel very old and so very tired inside, and my mirror is no kind flatterer and so does nothing to dissuade me. So to my eyes, as well as in my soul, I am a wizened old crone who has lived far too long. I’ve outlived all the love I’ve ever known, and such a life is not truly living, merely existing, waiting for the Sands of Life in God’s hourglass to run out. Inside I feel three hundred and fifty, though I’ve drawn breath only three-and-thirty years, and that’s not even half a single century. I should feel young and vital, but I’m all worn out. Years I’ve found are just a number; a convenient, or, depending on the circumstances, a not so convenient, calculation. Except when it comes to legalities I think in truth they count for very little. We are what we are, and a number does not define the marks the marching feet of Time, whisper light, carefree, or leaden, worry-weighted, have left upon us. I only know, if asked to guess my age, none would ever think me still young enough to bleed and bear a child. My face hangs weary, pasty pale, sagging, and heavily lined so any shadows that fall upon my face show how deep the sadness bites. My muddy grey eyes that I always used to despise and wish were instead a keen, piercing sapphire until my Thomas told me they were “like a cunning silver fox mating with a wily red one” rest in dark, wrinkled nests of flesh, and more wrinkles pucker round these rouge-reddened lips that still long for a lover’s kiss. And perched precariously atop my head sits my fashionable pearl-pinned wig of dark sable red curls, its colour as close to my own as I could find, though I dearly wish these great masses and mounds of high-piled curls would go out of fashion; I was born with an inordinately large head that always seemed to totter on my neck, too big for my squat, little goblin body, and this extravagant coiffure emphasizes it all the more. Beneath this flame-lit ebony monstrosity my short-cropped hair is white as the moon itself. I hacked it all off with my sewing scissors to the horror of my jailer, who found me sitting shorn and weeping amidst the scattered ruins of my tresses, when my scalp began to shed as profusely as my eyes did tears after I lost my Thomas.

Sometimes, when I lift off my wig before bed, I catch a glimpse in the looking glass of those wild wisps of moonstone white sprouting from my head like tufts of dandelion fluff, looking as though if a great gust of wind came along it would blow me bald-headed, and I just have to laugh. I am the only one of the Grey sisters to live to grow old and grey. “The brilliant one” and “the beautiful one” are long gone to their graves; only “the beastly little one” remains, growing more bent and beastly with every year that passes.

If I were to see those beloved spirits, my sisters and my husband, flying in through my window this All Hallows’ Eve, defying the sage burning there, would they even recognize me as their Mary? And if they came, I don’t know which I would doubt more, their existence or my sanity, nor which would hurt my heart the more—their coming or their going away again. I’ve already grown accustomed to living without them, to thinking every time I let myself start to feel again, to let fondness and care take root within my heart, those first tender shoots that herald the flowering of love in any of its many forms are also the first dip of the quill in the silver inkwell to begin the first grandiose curlicue of the word goodbye to be writ slow or fast across the pulsing rosy parchment of my heart. And I know, if they were to come to me this night, the one time of year, if tradition be true, that they can, they would disappear come cock’s crow, and I would be left all alone again missing them all the more. Stay away! No! Come to me! Come! Go! Yes! No! my contradictory heart cries, vying to be heard over the howl of the wind, the boom of the thunder, and the beat of the rain rapping like fingernails tapping on the glass windowpanes.

Beyond my window the dark hulk of the Tower of London looms like a monster in a child’s nightmare. I used to tell my husband I wanted a quiet life, a simple life, no great, grand palaces for me, thank you, I’d had all that before—Bradgate Manor in Leicestershire, luxurious London town houses, and the Queen’s many palaces—and love always meant far more than luxury to me. I only wanted him, my kind, sweet, gentle giant Thomas, and a little house of our own, with a room with a fine view to delight me while I sat and sewed. I had in mind a pretty garden with flowers and songbirds where I could watch my stepchildren and, God willing, the children born of our love, play, not see every day that morbid, frightening fortress where my eldest sister, Jane, went in a reluctant queen and died an innocent traitor. The place where my reckless, feckless father also died; to his very end he was a gambler who never knew when the game was lost and to hold on to what he had rather than risk losing all. And where my sister, Kate, birthed both her boys and made those cold stone walls burn with passion when her Ned, aided by a softhearted gaoler who thought it “a cryin’ shame that a ’usband and ’is wife should be made to lie apart these cold and many nights,” crept down the corridor into her bed. And my Thomas, my gentle giant, suffered his great, tall, broad form to be hunched and crammed, stuffed and squeezed into a tiny cell, and grew sick on rancid meat a dog wouldn’t eat. Perhaps that’s why I stay here? Though my love has never been inside this little house, all I have to do is look out my window and I can pretend he’s still alive, that only stone and mortar, locks and bolts, and not life and death, keep us apart, and that someday he’ll come back to me, that he didn’t die because of me.

Sage may keep the ghosts away, but not the memories; they constantly haunt the halls of my heart and the long and twisting corridors of my memory, like ghosts moaning and rattling their chains, demanding to be heard, to just be remembered, or to impart some dire warning or precious pearl of wisdom, so that from them I have no rest. But I don’t really mind. The memories, mementos, their letters and likenesses are all that are left to me now. They’re how I keep the ones I love alive, tucked safe inside my heart so that they can never truly leave me.

I have but one likeness of my husband, my Thomas, my Mr. Keyes, a miniature of a giant that shows only his great head and massive shoulders, but that’s all right; it’s all I need. The whole of him I shall never, can never, forget, even if I were condemned to walk this earth, like the Wandering Jew, until Christ’s return. Not even eternity could make me forget even one look, word, touch, or gesture of my Thomas; they are my greatest treasures, and I guard them as such.

My Thomas, he is—I suppose in all honesty I should say was, though in my heart he still lives, so when my heart is speaking I must say is—a lean, seven-foot-tall pillar of strength, broad in the shoulders and sturdy-limbed as Hercules, with a sprinkling of salt-and-pepper stubble hiding under his jaunty spring green velvet cap with the curling white plume and the brooch I gave him, a large silver lovers’ knot set with a great, round, rough-hewn emerald, a Samson who kept his strength even after he was shorn, and in fact preferred the razor’s smooth glide to watching the tide of his hairline recede with every passing year. Perky and sprightly he was, in bed and out, with a mischievous wink and cheery smile, and a love of flashy finery, his garments showy and bright as the most magical sunsets and the plumage of tropical birds. If ever a man loved vibrant, whimsical patterns upon his clothing, it was this man—his favourite garment was his gold-fringed, grass-green Noah’s Ark cloak over which marched just about every beast and bird known to man through a shower of embroidered raindrops worked in that perennially popular shade of blue-tinged white known as milk-and-water, presided over by a white-bearded Noah holding a shepherd’s crook, with the wooden ark embroidered across the back between the blades of my Thomas’s broad shoulders. And he loved every shade of green God or the silk dyers ever created, from the palest jade to the deepest forest.

My Thomas was not the lumbering dull-witted dolt many at a glance judged him by his mammoth size to be; it never ceased to amaze me how many people equated his height with stupidity, as if they imagined a brain the size of a pea rattling about within the immense ivory confines of his skull. He was in truth a man with an unquenchable curiosity about the world, avid to know all he could of medicine, science, and nature; each new advance and discovery enthralled him, and he always wanted to know more, to understand how and why. He also possessed a nimble mathematical mind and a love of words. I often saw him look up, the crystal lenses of the spectacles he wore to ease his eyes when he read flashing in the firelight, as he sat back in his chair, hands clasped behind his head, a book lying open upon his lap, and a thoughtful, faraway gaze, sometimes even tears, in his eyes as he contemplated the sheer beauty of the words he had just read. Just by stringing words together, like beads to make a necklace, he would marvel, the writer could reach right inside and touch the reader’s heart or give their mind a knock, set the gears a-turning, rouse curiosity, indignation, ire, or desire, or just make a body sit and ponder far into the night until the fire burned out and he was startled to hear the cock’s crow heralding the dawn of a new day.

Of my eldest sister, Jane, “the nine days’ queen,” I have a great many likenesses. There are portraits, full figure, half-length, and miniatures, some clad in the plain garb she favoured, some so stark they are nigh nunlike, others of such decadent jewel- and ermine-decked opulence they would have appalled and embarrassed my sister, painted on canvas, wood panels, porcelain, or ivory; there are crude woodcuts, exquisite pink and white carved cameos, elegant engravings, drawings of varying style and skill in rich or pallid paints, stark black ink, or charcoal pencil, their lines delicate or bold, and ornate illuminated manuscripts depicting Jane in a nimbus of radiant gold paint as if she were some kind of saint. All of them sent to me by well-wishers and admirers of my Protestant martyr sister, they form a whole beautiful beatified legion of Janes, most of them bearing little or no likeness to my sister except the approximate colour of her hair—though never the exact fiery chestnut that often appeared a deceptively boring brown—and the lily-white pallor of her skin, usually shown flatteringly unmarred by freckles. And none of them have her changeable eyes, as though when God created her He had daubed their greyness with paintbrushes dipped in brown, blue, and green. I have enough of these Janes—even a black-haired, violet-eyed Jane gowned in royal purple, ermine, and pearls, and a flaxen, rosy-cheeked Jane, buxom as a barmaid, in rose brocade trimmed with rabbit fur—to cover all four walls of my bedchamber and spill out into the quaint little parlour that adjoins it.

And there are also tracts, illustrated poems, and books, all lauding her with praise and heaping golden glories upon this proud, pious, and brave Protestant maid, and copies of her letters, preserved like sacred treasures, including her precious Greek New Testament inside of which she inscribed her last letter to Kate. There is even a kerchief stained with her blood—martyr’s blood, said to have the power to heal—a rather morbid memento sent to me when I was so ill after I had lost my Thomas. These are the relics of Lady Jane Grey.

The pictures I hang upon my wall; the rest I keep spread atop a table like offerings upon an altar. There is even a cloth weeping gold and bloodred fringe so that they touch silk instead of wood, with a scene depicting her last moments beautifully embroidered upon it, with silver gilt thread for the axe’s gleaming head. I keep it covered, for truly, however skillfully embroidered it may be, I have no desire to look at it; such talent should not have been squandered on such a ghoulish scene, better fruits and flowers than a girl of sixteen about to have her head struck off.

Sometimes, I confess, though inappropriate it may seem coming from me, for I truly do mourn my murdered sister, nonetheless, a chuckle sometimes escapes me as I behold these artists’ renderings. Some I think must be the work of lascivious old men hungry as starveling wolves for tender young flesh. For them the naked white neck and shoulders bare and white as milk above the black velvet gown are not enough, and they must go even further and strip Jane down to her stays and petticoats, as virginal and white as an innocent little lamb, and give the executioner a bulging codpiece, sometimes even painted a lusty red, nigh level with my sister’s face, though the blindfold mercifully shields her eyes from such a lewd sight. There is a sensuality about some of these images that offends and distresses me; it is as though the artists think the execution of this nervous and frightened sixteen-year-old girl was in some way erotic. How can they be so cruel and perverse? And how can they, the people who send me such pictures, think that I would want to see my sister thus?

Even before she died, people were already romanticizing Jane, making her into a tragic heroine, and forgetting that there was a core of mule-stubborn steel inside the delicate, dewy-eyed damsel who virtuously proclaimed that books were her only pleasure. And the stormy grey green eyes with a daub of blue and just a hint of hazel that the sentimentally inclined always thought were dewy with tears were in fact glimmering with the bold, mad, implacable gleam of religious fanaticism, flinty and hard as swords that longed to strike a blow for the Reformed Religion.

Jane wanted to be the Protestants’ Joan of Arc. Though young and fair, Jane was shrewd and canny; she wielded her formidable intellect like a sword, dazzling all with her fluent Latin and Greek, what she regarded as the more frivolous French, and the Hebrew she had been learning when she died, displaying as some women do their jewels her knowledge of Scripture and the ancient Greek philosophers. She laid the foundation for what was to come, aspiring to a kind of martyrdom even before the scaffold steps were in sight. Long before she achieved her royal destiny and tragic fame, she would heave doleful, heart-heavy sighs, raise her eyes to heaven, press a prayer book to her breast, and impart her tale of woe to any sympathetic and willing ear, so that the story of how she was most cruelly abused, pinched, slapped, and beaten by our lady-mother spread across Europe from one scholar to another as they imagined blood welling from her bare back and buttocks and scars tracing silvery white lines over her lily-white skin.

Once when I sat curled in a corner, having nodded off over my embroidery, I started awake when Jane and the esteemed scholar Roger Ascham came in. With my tiny form in its midnight blue velvet gown half hidden by curtains and shadows of a similarly dark hue, they did not see me and I was too shy to stir myself and alert them to my presence. Master Ascham said to Jane that there was more to life than books, and she should, as becomes a young lady of noble birth, go out into the world more. He gestured out the window, at the Great Park, where our parents were even then hosting a grand picnic after a vigorous day’s hunting. But Jane only sighed and hung her white-coiffed head while a rosy blush suffused her cheeks as she hugged her book tight against her black velvet breast, like a beautiful young nun confessing impure thoughts to her confessor. Then, with downcast eyes, my sister sank down onto the window seat and laid her volume of Plato on the black velvet cushion of her skirt as though it were a holy relic. “All their sport is but a shadow to the pleasure I find in Plato. Alas, good folk, they never felt what pleasure truly means!”

Master Ascham cocked his brow and smiled and queried her in mock seriousness. “And how attained you, madame, this true knowledge of pleasure seeing that so few men and women have arrived at it?”

“I will tell you, sir,” Jane confided, “and it is a truth perchance that you will marvel at. One of the greatest gifts that God ever gave me is that He sent me, with such sharp, severe parents, so gentle a schoolmaster as Master Aylmer. When I am in the presence of my parents I must, whether I speak, keep silent, sit, stand, or go, eat, drink, be merry, or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing, or doing anything else, I must do it soperfectly as God made the world, or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, and tormented, with slaps, pinches, nips, and blows and other chastisements—which I shall not name for the honour I bear my parents—that I think myself in Hell, till the time comes when I must go to Master Aylmer, who teaches me so gently, so pleasantly, with such fair allurements to learn, that I think all the time nothing while I am with him and am as a vessel to be filled with the knowledge he pours into me. And when I am called away from him, I fall to weeping, because whatever else I do but learning is full of great trouble and misliking for me. And thus my books have been so much my pleasure—nay, my only pleasure!—and all that others call pleasure is naught but trifles and troubles to me.”

“Oh, my dear child!” Master Ascham cried and tenderly pressed her lily-pale hand to his lips and held it there for a very long time.

I saw the smallest flicker of a smile twitch Jane’s lips, and at the time, being so young, I wondered if his long, curly beard was tickling her hand, or perhaps he was in love with her, and she like any other maid was preening over her conquest, but now, as a woman grown older and wiser, I suspect that it was his pity that gave her the greatest pleasure.

While it is true that Jane was beautiful—if she had smiled and radiated charm and winning ways, she would have rivalled Kate as the beauty of the family—she was not blessed with these gifts, nor did she make any effort to cultivate them. On the contrary, she disdained them and flaunted a frankness that bordered on insolence. Tolerance and tact eluded her. No matter how much we encouraged her or how hard our lady-mother tried to instill grace and charm through beatings and harsh punishments, Jane dug in her heels like a balky mule and refused to budge.

In matters of faith and fashion she was intractable, and over both, she waged many a battle, and even though she won many, I always, in my heart, felt that she always lost. As Kate always used to tell her, “You win more friends with smiles than with frowns, and honey catches far more flies than vinegar.”

But for all her brilliance and book learning, Jane lacked the ability to make herself liked. All she had was her intelligence, learning, and religious zeal to win her applause, accolades, and admiration. And she knew it. So if she could not be loved, she decided she would be praised and venerated. She saw herself as a victim, and she would make sure others saw her the same way, and she would shackle this idea to her strong, unwavering Protestant faith to create an image that would never be forgotten, as memorable, powerful, and inspiring as the Maid of France.

In many ways, Jane created her own myth. I loved my sister, but I sometimes wonder if I would have loved her if she had not been my sister. She was dour and gloomy, the kind of dull, dreary, and pedantic person who rains on every picnic. But as much as Jane scorned love, and urged us to turn away from the flesh and despise it and look to our souls instead, her need for it was all the greater, and she needed us—her sisters, who knew her best—to love her. She needed love in life more than she needed this posthumous fame and a glorious martyrdom. I wish she had lived long enough to find it. I longed to see Jane transfigured by love, true love, not just that tantalizing glimpse I caught of her in the dying throes of a girlish infatuation she once confided to us, or fighting furiously against and despising herself for her deep-buried and denied attraction to Guildford Dudley. I wanted to see her as a woman in love with all her sharp edges softened and beautifully blunted and blurred by bliss. But the allure of the victim, the sacrifice, the forever young and beautiful martyr, proved too strong, and Jane chose a remarkable and romanticized death, a potent and inspiring memory for posterity to glorify and cherish, over an ordinary life and the joy that can be found in the right pair of arms.

I have only two portraits of my sister Kate, my sunshine girl, along with the letters she wrote to me, tied up in bunches with silk ribbons the colour of ripe raspberries, and a jewelled and enamelled hand mirror shaped like a mermaid, a memento from her first marriage.

Sometimes I imagine I can see her laughing, happy face reflected in the oval of Venetian glass framed by the sea nymph’s flowing golden tresses. How strange it is, it always strikes me when I contemplate these pictures, that in both of them Kate, who loved bright colours so, is dressed in black and white. Where are her favourite fire opals and flashing green emeralds? Neither portrait does justice to her great beauty of face and heart. Both are miniatures, round with azure grounds, the paint made from pulverized lapis lazuli, painted by Lavinia Teerlinc, a dainty, flaxen-haired Flemish woman. The first shows Kate at thirteen, her hair more golden than copper then beneath a gold-bordered white satin hood. It was painted when she was still new-married to her first husband, Lord Herbert, and trying to look grown up in a high-necked gown of black velvet edged with white rabbit fur and gold aglets all down the front and trimming the slashed sleeves, her chin sinking deep into the soft cushion of a gold-frilled ruff. Beneath these stark and severe matronly black-and-white trappings, her bubbly vivacity and charm are smothered so that if only this picture survives down through the ages none will ever know what she was really like. And that saddens me; I want everyone to know and love Kate as I did, before she became the tragic heroine, with “all for love” as her creed, living and dying for love.

In the second portrait she looks sad and sickly, or “heart-sore” as the poets might say, blessed with that peculiar kind of beauty that sorrow in some miraculous way enhances; for Kate, though her fame is far eclipsed by Jane’s, is Love’s martyr, not Faith’s. This picture shows an older and sadder Kate at twenty-three, clad yet again in black velvet and white fur, a loose, flowing, sleeveless black surcoat through which her thin arms clad in tight-fitting white sleeves latticed with gold embroidery protrude like sticks, the bones and veins in the backs of her hands distressingly bold. In this likeness, Kate’s bright hair is subdued and hidden beneath a plain white linen coif devoid of ornamentation, not a stitch of embroidery, not even a jewelled or gilt braid border or even a dainty frill of lace. And, though it doesn’t show in this picture, her waist is thickening and her belly growing round again beneath the loose folds of black velvet with her second son, Thomas. Ned, the husband who held her heart in his hand, is with her in the form of a miniature worn on a black ribbon around her neck, and in the child they made together, the rosy-cheeked baby boy, named Edward after his sire. Kate holds her son up proudly, grandly garbed, like a little prince, in a black velvet gown I made for him, striped down the front with silver braid, and cloth-of-gold sleeves with white frills at his neck and wrists, his little black velvet cap twinkling with diamonds and trimmed with jaunty tawny and white plumes. He clutches a half-ripe apple, its flesh both rosy red and gold blurring into green, and one can almost imagine it represents the orb that is put in the sovereign’s hand on their coronation day. Kate holds her son in such a way that the ring Ned put upon her finger on their wedding day is on display for all to see, the famous puzzle ring of five interlinked golden bands, as well as the pointed sky blue diamond betrothal ring, both declaring that this baby in her arms is not some baseborn bastard, an infant conceived in hot lust and shame, but a legitimately born heir with royal blood from both the Tudor and Plantagenet lines coursing through his veins like a scarlet snake that could someday rear up and strike down the Queen if those who oppose this petticoat rule of Elizabeth’s ever dare to raise his banner and fight to take the throne in his name.

This picture looks like a warning in paint. If I were Elizabeth, or one of her counsellors, that is certainly how I would see it. But I know my sister better than any. Kate never coveted a crown for her children or herself. She was there and saw what happened to Jane. Kate steadfastly refused to follow in Jane’s footsteps, despite the urgings of others. Instead, she turned her back on the road of power and ambition and the golden throne that shone so bright it blinded the beholder to the scaffold lurking ominously in the shadows. The only ambition Kate ever harboured for herself, or her children, was to love and be loved. This is in truth a portrait of love, showing Kate with the three people she loved most—her husband, their firstborn son, and the one growing in the safe and loving warmth of her womb—and yet another example of my beautiful sister thinking with her heart instead of with her head.

And tucked inside my father’s battered old comfit box, its sky blue and rosy pink enamel chipped and worn, flaking off in places, nestled inside a bag of warm burgundy velvet, is a cameo carved with the profile of the most beautiful boy I ever saw—Jane’s husband, the vainglorious Guildford Dudley, when he was only sixteen and thought the world was an oyster poised to give up its precious pearl to him. That exquisitely carved profile is pure white, so I have only my memory to remind me of the gleaming brightness of his golden curls and the gooseberry green of his eyes. There was a grandiose portrait of Guildford clad head to toe in vibrant yellow and gold, but I don’t know what ever became of it. ’Tis a pity; I would like to have it here with me, to once again behold Guildford, who now lives only in my memory. Guildford, the golden boy whose whole life truly was a masquerade; a boy who died tragically young, before he could throw the mask away and become the person he always meant to be, or at least try to be, though that would have probably ended in tragedy and bitter disappointment too. Also inside that dear, dented box is another treasure—an intricately woven rose I fashioned from three long hanks of coiled and plaited hair—chestnut hiding ruddy embers, the richest coppery gold, and sleek sable sheened with scarlet—there we three sisters are, entwined in a loving embrace forever—Jane, Kate, and Mary.

Hanging upon my parlour walls are three wedding portraits, each showing a husband and his wife shortly after their nuptials.

The first shows the grandparents I never knew. The beautiful and spirited “Tudor Rose,” Mary Tudor, the youngest sister of Henry VIII. With her porcelain and roses complexion, blue eyes, and red-gold hair she reminds me of my sister Kate. She too dared all for love. When we were growing up how Kate used to beg to hear the story, told over and over again, of how our grandmother, who was as clever as she was beautiful, did not despair when she was forced to do her royal duty as every princess must and marry the ailing and decrepit King Louis XII of France, who had fifty-three years to her seventeen. Instead, she coaxed and wheedled and extracted a promise from her royal brother, Henry, who, like everyone else, adored her, that her second husband would be one solely of her own choosing. Oh what a merry dance she led gouty old Louis, bouncing out of bed at dawn and dancing until far past midnight! She wore him out within six months, and when he died, dwindled to a gaunt-faced shadow, exhausted from trying to keep up with his teenage bride, she married the man she had loved all along, her brother’s best friend, Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk. And they were gloriously happy until the day she died in 1533.

The portrait shows them in their wedding clothes, Mary, “The French Queen” as she would ever afterward be called, in chic black velvet embroidered with a fortune in pearls, some formed into exquisite rosettes, and rich golden roses set with sapphires to match her necklace. Her handsome, rusty-bearded bridegroom stands beside her, holding her hand, in sable-trimmed black velvet covered with silver piping with a row of silver-braided lovers’ knots marching down his chest. In her other hand, the newly wed duchess holds an artichoke, a pun on the orb she would have carried as queen, to show that she had disdained another royal marriage for one of true love, and also as an emblem of ardent love and fertility. I like to think that perhaps she already knew her firstborn child, my lady-mother, was already growing in her womb, like the leaves of an artichoke unfurling as it ripens.

The second portrait shows my parents dressed for the hunt. Hunting and gambling being the two passions that endured throughout their marriage, it seems somehow most appropriate that they chose to don these clothes for their wedding portrait. And it is how I best remember them. My lady-mother never seemed to be without her riding crop, and if satin slippers ever peeked from beneath her hems instead of gold or silver spurred leather riding boots, I do not remember. My lady-mother, Frances, the Duchess of Suffolk, stands in a grand gold-embellished russet velvet riding habit gripping her horse’s bridle in one leather-gloved hand and her riding crop in the other, a proud, fierce, willful, determined, voluptuous beauty, flesh already at war with the restraining influence of her corset, threatening to break out in open rebellion. She holds her head high, showing off her Tudor red hair, snared in a net of gold beneath her round feathered cap, and stares unwaveringly straight ahead with her shrewd ice-grey eyes, avaricious and calculating as a bird of prey eyeing a gentle, innocent sparrow with a wounded wing. There is something in the way she holds herself, her chin, firm and unyielding as chiselled granite, and the way she grips her riding crop that defines the words dominance and control. My father, Henry Grey, Hal to his wife and friends, stands beside her, auburn-bearded and handsome in a weak-chinned way in his white linen, brown velvet, and hunting leathers, with a hooded falcon on his wrist; he is a man awestruck, with the tentative smile and quizzical eyes of one who can’t quite believe his good fortune.

The third, and most unfortunate, wedding portrait shows my fat and florid piggy-eyed, sausage-fingered mother with her second husband, our Master of the Horse, Adrian Stokes, the boy of not quite twenty-one she married a scant two weeks after Father lost his head on Tower Hill. Her eyes remain the same, flinty, cold, and hard, but the hair has darkened, and the strong chin is softened by the pads of pink flesh that swaddle the bones, pushed higher still by a tall, most unflattering chin ruff with a fortune in pearls edging its undulating frills. And beneath the rich pearl-embroidered black velvet of her gown it is obvious that flesh has won a great, bursting victory over restraint, her defeated corset remains only as a nominal presence, because no proper lady would ever be seen in public without one; it has become an obsolete ornamental necessity that serves no actual purpose except to add one more expensive, luxurious embroidered layer to my lady-mother’s opulent person. She looks like she could devour the pale and slender black-haired boy standing beside her clutching his gloves as if they could save his life, and trying to look older than his twenty years, while showing off his grand gold and silver ermine-edged garments. Supported by a gold-laced ruff, his gaunt face always makes me think of the head of John the Baptist being offered to a most corpulent Salome, one who should keep her seven veils on instead of wantonly discarding them. Poor Master Stokes’s dark eyes seem to say his is a life of hard bargains, and also to question whether it’s really worth it—he’s risen in the world by marrying a duchess, the niece of Henry VIII, and mother of the best-forgotten nine days’ queen, but he doesn’t relish what will come afterward when they are alone together behind the bedcurtains and everything but our lady-mother’s riding boots comes off.

There is one more portrait in my parlour. A frosty, formal portrait of the cousin I was named for, the Tudor princess, and later queen, Mary, born of Henry VIII and his first wife, the proud and devout Spaniard, Catherine of Aragon. A plain and pious spinster, this Mary stands sunken-cheeked and stern-faced, severely gowned in high-necked black satin and velvet with a bloodred satin hood, petticoat, and full, padded under-sleeves; even the glimmer of the gold at her throat, breast, and wrists seems subdued and the jewels dulled amidst so much bloodred and black. Though it was painted years before people put “Bloody” before her name, at times I think it a prophecy in paint, a sign of things to come. Her hands are pure white and lovely, but I cannot look at them without seeing blood staining them.

Why do I keep it? Well … there was a time, many years ago, when my royal cousin and I shared a special kinship, something only the sad, hurt, lonely, passed over, and forgotten can truly understand. We both knew what it was like to live every day knowing that love, no matter how much we longed and dreamed of it, and needed it, was likely to pass us by and shower its blessings upon those pretty and fair. For us, even the royal blood in our veins might not be enough to tempt a husband. Cousin Mary had already dared to hope and been disappointed many times. With no husband or babies to give her time and love to, she would often come visit me, always bringing with her a basket filled with pretty scraps of material and bits of lace and gilt and gaudy trim she had been saving just for me, to fashion gowns for my doll, just as she had done for my other cousin, her half sister, the precocious, flame-haired Elizabeth, before Elizabeth, who was always old beyond her years, lost interest in dolls and turned her back on Mary and her sumptuous offerings, declaring them “a pastime fit only for babies.”

We would sit and sew for hours. She was the very soul of kindness and patience, and taught me so much of stitches and styles, patterns and cuts, the dressmaker’s craft and art. “Mayhap I flatter myself,” she would often say, “but if I had to make my way in the world, I fancy I could make a comfortable life for myself as a dressmaker.” It was true of Mary Tudor and equally true of me; my skill with the needle supplements my income and my embroidery is avidly sought after to this day. “There is magic in these fingers, little cousin,” she would say, taking my hands and kissing my stubby little fingers when I showed her my latest creation.

When a rainbow of silken threads and materials pass through her hands, a dressmaker soon learns that there are many shades of grey between black and white, and of these two stark colours that stand like sentries at the ends of the spectrum there are variations as well—charcoal, ink, raven, shimmering jet hiding a dark rainbow, rusty black with its bloody undertones, and midnight blue black, and the white of eggshells, ivory, milk, snow, and the silvery white glimmer of a fish’s belly, and the cream of custard and old lace. I cannot forgive Cousin Mary for taking Jane’s life, yet I cannot forget the love and kindness she lavished on me, a lonely, ugly, deformed child best kept hidden away, consigned to the shadows of shame, and I cannot take back or kill the love I gave her either. Master Stokes’s eyes speak truly, and his is not the only life filled with compromises and hard bargains.

And though I like not to look upon it, and keep it hanging, shrouded in shadows, in a dark corner downstairs in my humble dining room, there is my own portrait, the only one I have; there was once a miniature painted by Lavinia Teerlinc, long ago when I was just a child, but I don’t know where it is now, like so many other things, it has been lost. My Thomas wanted this portrait, so I sat for it to honour and please the one I loved most. Mercifully, it shows me only to my waist, so that those unaware of my stunted condition can gaze upon it without guessing that they are looking at a freak of nature. In a deep charcoal grey and black velvet gown discreetly embellished with silver embroidery and marching rows of shining bright buttons, with puffs of rose-kissed white satin protruding through my short, slashed over-sleeves, and a profusion of beautiful blackwork Spanish embroidery and gold wrist and neck frills decorating the delicate lawn of my under-sleeves and partlet, and ropes of blushing pearls layered at my throat, I stare warily out at the world, proudly displaying the gold ring set with the “mystic ruby” my husband put on my finger on our wedding day. He kissed my hand and said it would protect me always, even when he could not, and safeguard me from all poisons and plagues, explaining that this bloodred cabochon, so rich a hue that its light shines even through fine linen, was forged from the crystallized blood of a very old and wise unicorn that congealed when its horn was severed. And upon my little black velvet cap is a pink gillyflower, to tell all those who look upon my portrait that here is painted a loyal and loving wife. And arranged behind it, prophetically posed just above the pink gillyflower, is a silver pin from which teardrop pearls drip like a shower of tears. Yes, I still weep for my husband.

A scorching whiff suddenly reminds me of the cakes I have left baking in the ashes, thankfully before they burn. My rusty knees creak and pop in protest as I kneel to retrieve them—three warm, round, golden honey cakes, each decorated with red currants to spell out one dear initial—J for Jane, K for Kate, and T for Thomas—the three people I loved most. The red currants look like scabs of newly dried blood, and I shudder at the sight of them, thinking of the beloved blood that was spilled in vain. And as the wind howls outside my window, I think I can almost hear them calling my name as my mind journeys back to the long ago February day when our lives changed forever, when we three sisters found ourselves standing at a crossroads and realized that the moment had come when we must all take different paths. Solemn, sullen Jane, “the brilliant one,” took the road to the scaffold and a martyr’s fame, and saucy, carefree Kate, “the beautiful one,” skipped along light and airy as a butterfly with jewel-coloured stained glass wings, following her heart wherever it might lead, living, and dying, all for love, and I, “the beastly little one,” thought I was destined to always walk alone, shrinking fearfully into the shadows to hide from those who passed me by lest they wound me with their words, laughter, blows, or even worse, the pity in their eyes. I thought for certain that Love, though he would surely stop for Kate and might even pause for Jane, if she let him, would pass me by.

1 (#ulink_3e588889-62c1-5438-abf3-c9c145378871)

Only a fool believes in Forever. Yet I was a fool, though I was only five years old at the time—take that as an excuse or not as you like—when my eldest sister, Jane, came home to Bradgate after the death of the much beloved Dowager Queen Catherine Parr, the sixth and final wife of our magnificent, fierce uncle, King Henry VIII. Jane had been the sixth queen’s beloved ward and lived with Catherine and her new husband, the Lord Admiral Thomas Seymour, quietly pursuing her studies, until death and heartbreak brought her home to us. That was in September 1548, and Jane was a month shy of eleven, though her intelligence and quiet, solemn ways always made her seem much older than her actual years.

We would be constantly together in the years to come, we three sisters—Jane, Kate, and I, “the brilliant one, the beautiful one, and the beastly little one!” as we used to laughingly call ourselves as we stood together before the looking glass, poking fun at the way everyone saw us, like characters in a fairy tale. Rather than rage, pout, or weep, we had adopted it as our own and laughed about it instead. I didn’t think then of marriage, of husbands, households, and babies, the responsibilities that would inevitably tear us apart, take us away from our home at dear rosy-bricked Bradgate in Leicestershire, and each other, and divide us from a trio of sisters into three separate lives. I thought we would go on forever, always together.

Jane was so sad when she came home that long ago September. Never before had I seen her so listless and full of sorrow. When she stepped down from the coach, she moved like one in weighted shoes, stunned by a heavy blow to the head, as though she were walking in her sleep, her swollen, red-rimmed eyes open but oblivious, even to Kate and me as we ran out with open arms and joyful, eager smiles to welcome her. But Jane didn’t notice us. Even when Kate hurled herself at her, like a cannonball covered with bouncing copper curls, Jane absorbed the impact with barely a flicker. When I saw this, my smile and steps faltered and I hung back, feeling as though I were trespassing on my sister’s sorrow, even though all I wanted to do was banish it.

She was still wearing the black velvet gown she had worn to the Dowager Queen’s funeral, where she had acted as chief mourner, with her long, wavy chestnut hair still pinned tight and confined beneath a plain white coif, and her thin shoulders shivering under the little white silk capelet, both of which, coupled with the black gown, signified that the deceased had lost her own life bringing a new life into the world. With two black-gowned, white-coiffed, and caped maids bearing her long black train, Jane, carrying a lighted white taper clasped tight between her trembling hands, hoping her tears would not drip down and douse the flame, had led the grim and solemn procession into the chapel at Sudeley Castle.

Our always elegant lady-mother disembarked from the coach with a wave of rose perfume strong enough to knock any weak-stomached man or maid down, her leather stays creaking in violent complaint beneath the grandeur of her gold-embroidered green velvet gown and her favourite leopard skin cloak. Our father had given it to her when she, as a young bride, triumphantly announced that she was carrying a child that they were both confident would be a son, though it was in fact Jane in her womb as time would reveal. But our lady-mother kept and prized her leopard skin cloak just the same, even long after she had given up all hope of a son. “I deserve it,” I often heard her proclaim as she preened before her mirror with it draped about her broad shoulders. “After all that I have endured—I deserve it!” Though I never dared question her, I knew she meant us—Father’s weak will and his body grown cushiony soft through unrestrained indulgence of his love for sweets; Jane’s recalcitrant and willful ways that ran so contrary to our world’s most cherished ideas of feminine beauty and charm; Kate’s thinking with her heart instead of her head; my stunted, deformed body—a dwarf daughter is a daughter wasted, she can do no good for her family or herself; and the tiny baby boys born blue and dead with limp little phalluses that waggled mockingly, reminding our parents of the son, the star of the Grey family, the hope of the future, they would never watch grow to strong and lusty manhood and carry on our proud and noble lineage.

Jane blindly followed our lady-mother toward the house, meek and docile in her grief, her long train trailing forgotten over the dusty flagstones behind her. Her mind shrouded in black velvet sorrow, Jane didn’t feel its weight or hear the rustling whisper that tried to remind her, like a little voice urgently hissing, Pick me up!Pick me up! Sudden as a serpent striking, our lady-mother swung around and dealt Jane’s face a sharp leather-gloved slap that almost knocked her down. “Pick up that train!” she snapped, though we all knew it was a gown Jane would never wear again, for every stitch of that hastily sewn frock was full of sorrow.

Jane staggered and stumbled backward, a livid pinkness marring the milky, cinnamon-freckled pallor of her cheek and a drop of blood falling like a ruby tear from her nose to stain her white silk capelet. Seeing it, our lady-mother snorted like a horse, blowing hot fury, before she shook her head in a way that seemed to say to Jane, You’re hopeless! and spun on her leather-booted heel and flounced into the house, the feathers on her hat bobbing with every step as she nimbly plucked the gloves from her fingertips, tossed them to a maid, and untied her cloak strings, as she called for wine and demanded the whereabouts of her husband. As soon as the door closed behind her, Kate ran to gather up Jane’s train, bunching up the dusty velvet, wadding it against her chest as best she could, being quite daintily built and only eight. And I took Jane’s hand and gave a gentle tug to get her moving and led her inside and upstairs to her chamber.

Jane never said a word as her nurse, Mrs. Ellen, ordered her to sit, and then, with an efficiency born of familiarity, silently bathed Jane’s face and pressed a cold cloth to her nose to staunch the bleeding while Kate and I knelt beside her chair and held and rubbed our sister’s hands. As soon as a servant appeared bearing Jane’s trunk, she sprang up and ran to open it. From inside she took a portrait, which she had wrapped in petticoats to protect it on the journey. She unswaddled it tenderly as a mother would her child, as Catherine Parr would never have the chance to do for her own infant daughter, then propped it on a chair and sat back on her heels before it.

It was a portrait of the late Dowager Queen, gowned in sumptuous claret satin, her bodice and sleeves elegantly embellished with gold-embroidered black bands. Her auburn head was covered by a round, flat black velvet cap adorned with fanciful gold and pearl buttons and brooches. With its jaunty, curling white plume, the hat looked far more cheerful than the pensive pearl-pale face unsmilingly framed by the pearl-bordered white coif she wore beneath it. In the hollow of her pale throat I noticed was a pendant I had seen on portraits of our uncle’s previous queens, all now deceased, their lives bled out in childbed or on the scaffold, a great cabochon ruby resting in a nest of gold acanthus leaves with a smaller emerald set above it and an enormous milky teardrop of a pearl dangling beneath.

I had never met Queen Catherine, but Jane had told me so much about her I felt I knew her: the book she had written, TheLamentation of a Sinner, a labour of love boldly espousing woman’s equality to man, emphasizing femininity’s Christlike virtues, such as meekness and humility; the finely arched brows she plucked with silver tweezers; the discreet henna rinses she applied to her hair when her husband was absent; and the quick pinches she gave her cheeks, to give them colour, before she came into his presence; the milk baths she soaked in to keep her skin soft and fair; the vigorous scrubbings with lemons to fade and discourage freckles; the rose perfume she distilled herself from her own mother’s recipe; the cinnamon lozenges her cook prepared in plentiful batches to keep her breath sweet; and the red, gold, and silver dresses her dressmaker made to show off the still slender figure of an ageing woman who kept her waist trim by exerting steely self-discipline at the dining table, shunning the rich, decadent fare laid before her on gold and silver plates, and, to her great sorrow, by never having borne a child. All to keep a man who wasn’t worth keeping, an ambitious scoundrel who lusted after a crown and was hell-bent on seducing her own stepdaughter—the flaming, vital, young Princess Elizabeth who stood just two steps down from the throne her brother sat upon. Only her sister, the Catholic spinster Mary, stood above her in the line of succession, and she had already rebuffed the Lord Admiral’s passionate overtures.

Kate and Mrs. Ellen each bent and took Jane by the arm and raised her. As we undressed her, Jane never said a word or took her eyes off Catherine Parr’s face.

Later, when the house was still, and the yawning, sleepy-eyed servants had climbed the stairs to their attic cots, and our own nurses lay snoring on the trundle beds, Kate and I crept on bare toes back to Jane’s bedchamber, hugging our velvet-faced damask dressing gowns tight over our lawn night shifts lest their rustling betray us. Jane lay white-faced and still behind the moss green and gold brocade bedcurtains with the covers drawn up to her chin. The cups of mulled wine Mrs. Ellen had given her had eased her, warmed her inside, and loosened her usually cautious tongue. We roused her and, to our delight, found she was no longer a walking wraith and once again our dear, difficult, but much beloved sister. And as we huddled beneath the bedcovers, close as three peas in a pod, Kate still in her green velvet dressing gown and I in my plum one, Jane shared with us the strawberries, pears, apples, and walnuts sympathetic common folk, who also mourned the Dowager Queen’s passing, had given her whenever the carriage stopped so that the horses could be changed or watered. “They were all so kind,” Jane said in an awed little whisper as though human kindness was something strange and marvellous she was unaccustomed to behold.

It was then, as we munched our treats and sipped the now tepid wine Mrs. Ellen had left behind, that our sister confided all. And what tales she had to tell! Had it been anyone other than our plainspoken Jane I would have suspected some fanciful embroidering. She told us all about the lewd, wanton romps that had astonished and titillated all of England when they heard how the Lord Admiral had made it his custom to creep into Princess Elizabeth’s bedchamber early each morning to rouse her with tickling and kisses, handling her person in a most familiar and intimate fashion, and how the two had been surprised in an embrace by his wife, with the guilty fellow’s hand roving beneath the princess’ petticoats, which had resulted in Elizabeth being sent away, and had spoiled Catherine’s joy in at long last finding herself with child. In the delirium of the fever that followed the birth of her daughter, Catherine’s tongue had scourged her husband and stepdaughter like a metal-barbed whip; she accused the Lord Admiral of wanting her dead so he would be free to marry Elizabeth, his little wanton strumpet of a stepping stone leading straight to the throne. And Jane had with her own eyes seen him pour a white powder into a goblet of wine and press it to Catherine’s lips, forcing her to drink, tightening his grip and pressing the golden rim harder against her lips when she shook her head and tried to pull away, and afterward holding his hand over her mouth to make her swallow when he thought she might attempt to spit it out. She died with small, round, livid purple-red bruises from his fingertips marring her cheeks and jaw. When the time came to bathe and clothe her corpse, her favourite lady-in-waiting, a stepdaughter from Catherine Parr’s first marriage, Lady Tyrwhit, had painted over them with a paste of white lead and powdered alabaster to restore her complexion to pearly consistency.

Before Catherine died, a lawyer was summoned—Jane herself opened the bedchamber door to let him in—and the Lord Admiral prompted his fading wife to dictate a new will leaving all her worldly goods to him, thus making him a very rich man. He even gripped her hand and guided it across the parchment to sign her name, leaving bruises upon her knuckles that Lady Tyrwhit would also lovingly conceal. It disturbed Jane to recall how hard he had held her hand, hard enough to make the bones crackle and grate as if his bride’s very bones protested his cruel, duplicitous ways. “There was naught of love in his touch, no tenderness, only cruelty and a determination to have his will,” Jane said. “I wanted to do something, I wanted to stop it, but I was as helpless and powerless as the Dowager Queen was in the end. He as her husband had all the power.”

But there was more, much more—the kinds of secrets that weigh so heavily upon a young girl’s heart.

“I too sinned against the Dowager Queen,” Jane, in a voice suffused with shame, confided. “She was more like a mother to me than our own—patient, loving, encouraging, and kind, so very kind—and I wronged her just as Elizabeth did, only she never knew it; I was not found out.”

She went on to tell us how Thomas Seymour had fanned the flames of our parents’ ambition by concocting a grand scheme to marry her to the young King Edward. Outwardly it seemed a perfect match, Jane and Edward both being the same age, English, and devout Protestants, of serious rather than merry mind, and Jane had been named in honour of the King’s mother, Jane Seymour, the third and most beloved of Henry VIII’s six wives. Though the young king, who was after all only a pale, frail boy trying hard to ape his splendid sire, in padded shoulders and plumed hats, posing with fists on hips and feet in slashed velvet duckbill slippers planted wide apart, pompously proclaimed that he wanted a “well-stuffed and jewelled bride” for himself, his “jolly Uncle Tom,” who provided the young monarch with pocket money to earn his favour and gratitude, was certain he could persuade him that “what England needs most is a homegrown Protestant queen, a true English rose, like the Lady Jane Grey, who will uphold the Reformed Faith, not a French Catholic princess hung with jewelled crucifixes, dripping pearl rosaries, kneeling on an embroidered prie-dieu, and throwing boons to her pet cardinals and confessors.” Brash Tom Seymour had so much confidence in his own schemes he “could sell fire and brimstone to the Devil,” our lady-mother used to say as she toed a cautious line while our father wholeheartedly embraced the dream of seeing his firstborn daughter crowned queen.

But no one asked or cared how Jane herself felt about the future that was being planned for her. She did not want to marry Edward; she felt the coldness emanating from him like a great blast of icy air so that even in summer she shivered and longed for her furs whenever she was in his presence, and she saw cruelty glinting in his eyes, and that made her tremble and fear the man he would grow up to become. And she didn’t want to be queen either. All Jane wanted—or thought she wanted—was her books, to spend her life quietly engaged in study.

Like a nun taking the veil and becoming the bride of Christ, Jane wanted to dedicate herself to the Reformed Faith; she wanted no man or marriage to interfere and had no time or patience for romance and even turned up her nose and scoffed derisively at the very idea. Many a time I heard her chastising Kate for being more avid for love than learning and urging her to “despise the flesh.” Jane thought carnality was a vile, evil, disgusting thing and didn’t want it to sully her life in any way, not even in songs or stories; anyone she caught indulging in either she told to their faces that they should be singing hymns and reading Scripture instead. Rather fanatical upon this subject, she urged everyone to “despise the flesh” and resented any carnal intrusion into her life, even if it were only by accident.

I remember once when we were going riding and walked in on one of the stable boys coupling with a wench on a bed of straw in a horse stall, Jane turned right around, strode straight back into the house, even as the boy and girl ran after her, half dressed, pleading for mercy, that they were in love and planned to be married soon, and reported the incident to our lady-mother and had them both dismissed from our service. And another time when she caught Kate sighing dreamily over a pretty picture of lovers kissing in a garden, Jane snatched the book from her, tore and broke its binding, and flung the whole thing into the fire and ran to wash her hands in scalding water, claiming they were as soiled as though she had just handled manure.

Such heated reactions were all too typical of Jane, and our lady-mother said she pitied the man who would one day marry her as he would no doubt find Jane a very cold bride with “a cunny like ice.” Then Thomas Seymour came along like a whirlwind, sending books, papers, pens, and Jane’s own thoughts flying every which way in wild disarray, leaving all so disordered she didn’t know which way to turn or how to begin to put it all right again.

It all began with a walk in the garden at Chelsea, Catherine Parr’s redbrick Thames-side manor, a talk about self-sacrifice and destiny, and one perfect pink rose. Catherine was busy with the dressmaker, having extra panels and plackets sewn into her bodices and skirts to better accommodate the child growing inside her, and she had asked Elizabeth to bear her company and help in the selection of materials for some new gowns she had impulsively decided to have made, complimenting her stepdaughter’s sense of style and colour, the bold choices she made that another woman with ruddy-hued hair might shy away from. “I need to borrow a little of your bravery, my dear,” Jane heard her say softly as she reached out a hand for Elizabeth’s. Perhaps it was only a charade to keep her stepdaughter in her sight and away from her husband, but sincere or feigned diversion, either way Elizabeth couldn’t say no without appearing impolite and ungrateful to her stepmother and hostess.

So Jane, who had no interest in such fripperies and believed that “plain garb best becomes a Protestant maid,” was left to amuse herself and nurse the still healing bruises from a recent visit to Suffolk House in London where she had dared show herself “balky and sulky” at the prospect of becoming King Edward’s bride, boldly proclaiming that she didn’t want to marry at all, but to remain a lifelong virgin and give all the devotion a girl is expected to give her husband and children to the Reformed Faith instead.

Our lady-mother had worn out her arm and painfully pulled a muscle trying to horsewhip such “nonsense” out of Jane and had to have the doctor in to poultice and bind it. She was angry as a baited bear for a week afterward since her injury forced her to stay home and forgo the pleasure of several hunting parties. And without her restraining presence, Father had gained several pounds at the picnics and banquets that attended these events and had to have most of his clothes let out.

When our lady-mother heard that he had devoured the entire antlered head of a marzipan stag at the banquet following a royal hunt, she nearly screamed the house down and yanked several of his hunting trophies, his treasured collection of heads and antlers, from the wall and hurled them downstairs. Poor Father only narrowly avoided being impaled by the magnificent antlers of the king stag he had slain at Bradgate. And whenever our father came home, cheeks ruddy from riding hard in the bracing wind, the blood of the kill staining his hunting clothes, in a high good humour ready to boast of his prowess, our lady-mother would send a goblet of wine or a platter of food flying at his head and sulk all the more because she had missed all the fun, the thrill of being in the lead herself, the knife clutched in her hand, seeing the blade glinting in the sun, the scent of blood hovering like perfume in the air accompanied by the music of buzzing flies as she closed in for the kill, and woe to Jane, the cause of her missing her favourite pastime, if she happened to cross our lady-mother’s path at such a time.

That day at Chelsea, the Lord Admiral had found Jane curled up in a window seat, extra petticoats beneath her plain grey gown cushioning her still tender buttocks and thighs, with an apple in her hand and a book open on her lap, brow furrowed intently beneath the plain grey crescent of her French hood as she pored over the pages, lips moving as she translated the ancient Greek of Plato’s Phaedo.

“A pox upon Plato, it’s too lovely a day, and you’re too lovely a maid to squander on a musty old Greek!” he exclaimed, causing Jane to almost jump out of her skin as he snatched the book and flung it away, giving Mrs. Ellen quite a fright. The poor lady had fallen into a doze over her sewing and suddenly awakened to find her headdress knocked askew by a black-bound volume of ancient philosophy that had come flying at her like a bat.

“Come out and walk with me, Jane!” the Lord Admiral insisted. And, before she could demur, he already had hold of her hand and was pulling her out into the sunshine, even as she stumbled over her hems and glanced back helplessly and shrugged her shoulders at poor Mrs. Ellen.

When Mrs. Ellen regained her senses and ran after them, protesting that the Lady Jane must first put on a hat, to protect her complexion as she was prone to freckling, the Lord Admiral took the straw hat she held and sent it sailing across the rose garden where the breeze took it up and landed it upon the river, declaring that he loved freckles, and blushes too, as they lent character to faces that would otherwise be as pale and boring as marble statues, and that for every new freckle the Lady Jane acquired from their little walk he would give her, and Mrs. Ellen too—he paused to flash the nurse a saucy wink—three kisses. And that was the end of that. He gave Jane’s hand a tug and set off along the garden path at a brisk pace, and Mrs. Ellen was left standing there alone, gaping after them, wringing her hands, feeling quite flustered, and wondering whether she should feel charmed by the Lord Admiral or insulted and go straight inside and complain to the Dowager Queen. The Lord Admiral tended to have that effect upon people.

He led Jane out, beyond the garden, into the Great Park, where a blanket was spread beneath the broad branches of one of the ancient and majestic oaks. And while Jane sat modestly arranging her skirts, eyeing with dismay the grass stains and tears upon the hem that had marked their hurried progress, the Lord Admiral took from a basket a plate of “still warm” golden honey cakes, a flagon of ale, two golden goblets wrought with true lovers’ knots all around the rim, and a lute bedecked with gay silk ribbon streamers. And then he began to sing, slowing the jaunty, rollicking pace of the salacious tavern ditty to a sensual caress, like a velvet glove, lingering over, savouring, certain words, as his warm brown eyes met Jane’s, and his fingers plucked the lute strings in such a brazen way that called to mind what they might do if given free rein to rove over a woman’s body.

I gave her Cakes and I gave her Ale,

I gave her Sack and Sherry;

I kist her once and I kist her twice,

And we were wondrous merry!

I gave her Beads and Bracelets fine,

I gave her Gold down derry.

I thought she was afear’d till she stroked my Beard

And we were wondrous merry!

Merry my Heart, merry my Cock,

Merry my Spright.

Merry my hey down derry.

I kist her once and I kist her twice,

And we were wondrous merry!

At the end, as the last notes hovered in the air, he leaned forward and pressed his lips softly against Jane’s.

“There now,” he said, “whatever happens, I shall always be the first. Come what may, whether you are ever Queen of England or remain only Queen of My Heart, my darling Jane, I will always be the first man to kiss Lady Jane Grey, and no one can ever take that away from me; that honour—that very great honour—will be mine forever.”

Jane sat back on her heels blinking and befuddled. “M-My L-Lord, wh-what … what are you saying?”

The words had scarcely left her lips before she found herself enfolded in Thomas Seymour’s strong embrace, pressed suffocatingly tight against his hard, muscular chest in such a way that the pins holding her hood in place stabbed into her scalp like tiny knives, some of which Mrs. Ellen would later discover, when she helped Jane prepare for bed that night, had actually drawn blood.

“What am I saying?” he repeated. “Only that I love you, darling Jane, I love you! I love you! I love you! Can you not hear it in every breath I take, in every move I make, in every beat of my heart? I love you, Jane, I love you! You—only you!”

And then he let her go, so abruptly that Jane fell back onto her elbows and almost crushed the lute. With a resigned, defeated sigh, he sat back, but as he did so he deftly caught up her hand. With one last smouldering gaze and heart-tugging sigh, he took a moment to compose himself before he shut his eyes and then, reverently, bowed his head and pressed his lips chastely against the back of her trembling hand. “But, for England’s sake, for the greater good, I must sacrifice my heart and let you go,” he said with a crestfallen sigh. “You, my darling, were meant for far greater things than I can give you. You were meant to wear a crown and be the torch that leads the English people out of the Papist darkness into the light of the Reformed Faith! You, my darling, as much as it hurts me, must be Edward’s helpmeet, not mine.”

“But I don’t want to marry Edward!” Jane protested, for the first time giving voice to her feelings. “He … he … frightens me! And I don’t … I don’t … love … him.”

“I know you don’t, my darling.” Thomas Seymour enfolded her in his arms once again. “And I don’t blame you. No one loves Edward, not really! He is my own nephew, the son my own beloved sister lost her life giving birth to, yet I cannot find it in my heart to love him and must in his presence resort to playacting. He is as chilly as a fish, a frigid little prig who takes himself far too seriously. He has none of his great sire’s charm or the common touch, and no sense of fun, and he knows nothing of love and warmth and has no desire to learn. But you must marry him, my love; it is your destiny to be Edward’s godly and righteous, virtuous and learned queen; united together you will be the rulers of a new Jerusalem, the thunderbolt of terror to Papists everywhere; your reign will be the death blow to the Catholic faith in England! We must each sacrifice our own hearts, and deepest desires, for the greater good, for England, and the Reformed Faith, my darling. Our love shall be the martyr of duty!”

He pulled the hood from her head and plucked the pins from her hair and stroked it before drawing her close again and pressing his lips warmly, tenderly against her temple. “When you lie in his arms, think of me, darling Jane, think of me and how my heart beats only for you! We will always have our dreams to console us and the knowledge that they were sacrificed, selflessly, for the greater good. And as cold as Edward is, always remember, my love for you is pulsing hot, and it will keep you warm and give you the strength to go on and do your duty, as you must, indeed, as must we all.