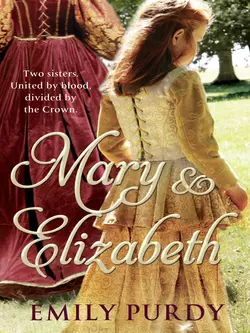

Mary & Elizabeth

Emily Purdy

Two sisters: united by blood, divided by the crown…Mary and Elizabeth is an unforgettable story of a powerful love affair that changed the course of history, perfect for fans of The Tudors and Philippa Gregory.They shared childhood memories and grown-up dreams…Mary was England's precious jewel, the surviving child of the tumultuous relationship between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. However, when Henry fell passionately in love with the dark-eyed Anne Boleyn, he cast his wife and daughter aside.Henry and Anne's union sees the birth of Elizabeth. Mary is soon declared a bastard, stripped of all royal privileges, performing the lowliest tasks. But, there is something about Elizabeth. And Mary soon grows to love her like a sister.After the passage of three years, and Anne Boleyn's execution, Henry can no longer bear the sight of his female heir. With the birth of a son, Edward, both Mary and Elizabeth seem destined for oblivion. But as history will show, fate had something far more elaborate in store…

Mary & Elizabeth

Emily Purdy

Contents

Prologue

The End of an Era

1

Mary

2

Elizabeth

3

Mary

4

Elizabeth

5

Mary

6

Elizabeth

7

Mary

8

Elizabeth

9

Mary

10

Elizabeth

11

Mary

12

Elizabeth

13

Mary

14

Elizabeth

15

Mary

16

Elizabeth

17

Mary

18

Elizabeth

19

Mary

20

Elizabeth

21

Mary

22

Elizabeth

23

Mary

24

Elizabeth

25

Mary

26

Elizabeth

27

Mary

28

Elizabeth

29

Mary

30

Elizabeth

31

Mary

32

Elizabeth

33

Mary

34

Elizabeth

35

Mary

36

Elizabeth

37

Mary

38

Elizabeth

39

Mary

40

Elizabeth

41

Mary

42

Elizabeth

43

Mary

44

Elizabeth

45

Mary

46

Elizabeth

47

Mary

48

Elizabeth

49

Mary

50

Elizabeth

51

Mary

52

Elizabeth

Postscript

A Reading Group Guide

Discussion Questions

About the Author

Other Books by the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

The End of an Era

January 28, 1547

Whitehall Palace

Wonderful, dangerous, cruel, and wise, after thirty-eight years of ruling England, King Henry VIII lay dying. It was the end of an era. Many of his subjects had known no other king and feared the uncertainty that lay ahead when his nine-year-old son inherited the throne.

A cantankerous mountain of rotting flesh, already stinking of the grave, and looking far older than his fifty-five years, it was hard to believe the portrait on the wall, always praised as one of Master Holbein’s finest and a magnificent, vivid and vibrant likeness, that this reeking wreck had once been the handsomest prince in Christendom, standing with hands on hips and legs apart as if he meant to straddle the world.

The great gold-embroidered bed, reinforced to support his weight, creaked like a ship being tossed on angry waves, as if the royal bed itself would also protest the coming of Death and God’s divine judgment.

The faded blue eyes started in a panic from amidst the fat pink folds of bloodshot flesh. As his head tossed upon the embroidered silken pillows a stream of muted, incoherent gibberish flowed along with a silvery ribbon of drool into his ginger-white beard, and a shaking hand rose and made a feeble attempt to point, jabbing adamantly, insistently, here and there at the empty spaces around the carved and gilded posts, as thick and sturdy as sentries standing at attention, supporting the gold-fringed crimson canopy.

There was a rustle of clothing and muted whispers as those who watched discreetly from the shadows – the courtiers, servants, statesmen, and clergy – shook their heads and shrugged their shoulders, knowing they could do nothing but watch and wonder if it were angels or demons that tormented their dying sovereign.

The Grim Reaper’s approach had rendered Henry mute, so he could tell no one about the phantoms that clustered around his bed, which only he, on the threshold of death, could see.

Six wronged women, four dead and two living: a saintly Spaniard, a dark-eyed witch – or “bitch” as some would think it more apt to call her – a shy plain Jane, a plump rosy-cheeked German hausfrau absently munching marzipan, and a wanton jade-eyed auburn-haired nymph seeping sex from every pore. And, kneeling at the foot of the massive bed, in an attitude of prayer, the current queen, Catherine Parr, kind, capable Kate who always made everything all right, murmuring soothing words and reaching out a ruby-ringed white hand, like a snowy angel’s wing, to rub his ruined rotting legs, scarred by leeches and lancets, and putrid with a seeping stink that stained the bandages and bedclothes an ugly urine-yellow.

Against the far wall, opposite the bed, on a velvet-padded bench positioned beneath Holbein’s robust life-sized portrait of the pompous golden monarch in his prime and glory, sat the lion’s cubs, his living legacy, the heirs he would leave behind; all motherless, and soon to be fatherless, orphans fated to be caught up in the storm that was certain to rage around the throne when the magnificent Henry Tudor breathed his last. Although he had taken steps to protect them by reinstating his disgraced and bastardized daughters in the succession and appointing coolly efficient Edward Seymour to head a Regency Council comprised of sixteen men who would govern during the boy-king’s minority, Henry was shrewd enough to know that that would not stop those about them from forming factions and fighting, jockeying for position and power, for he who is puppetmaster to a prince also holds the reins of power.

There was the good sheep: meek and mild, already greying, old maid Mary, a disapproving, thin-lipped pious prude, already a year past thirty, the only surviving child of Catherine of Aragon, the golden-haired Spanish girl who was supposed to be as fertile as the pomegranate she took as her personal emblem.

The black sheep: thirteen-year-old flame-haired Elizabeth, the dark enchantress Anne Boleyn’s daughter, whose dark eyes, just like her mother’s, flashed like black diamonds, brilliant, canny, and hard, as fast and furious as lightning; a clever minx this princess who should have been a prince. Oh what a waste! It was enough to make Henry weep, and tears of a disappointment that had never truly healed trickled down his cheeks. Oh what a king Elizabeth would have been! But no petticoat, no queen, could ever hold England and steer the ship of state with the firm hand and conviction, the will, strength, might, and robust majesty of a king. Politics, statecraft, and warfare were a man’s domain. Women were too delicate and weak, too feeble and fragile of body and spirit, to bear the weight of a crown; queens were meant to be ornaments to decorate their husband’s court and bear sons to ensure the succession so the chain of English kings remained unbroken and the crown did not become a token to be won in a civil war that turned the nation into one big bloody battlefield as feuding factions risked all to win the glittering prize.

“Oh, Bess, you should have been a boy! What a waste!” Henry tossed his head and wept, though none could decipher his garbled words or divine the source of his distress. “Why, God, why? She would have held England like a lover gripped hard between her thighs and never let go! Of the three of them, she’s the only one who could!”

And last, but certainly not least – in fact, the most important of all – the frightened sheep, the little lost sheep, the weak and bland little runt of the flock: nine-year-old Edward. So soon to be the sixth king to bear that name, he would be caught at the centre of the brewing storm until he reached an age to take the sceptre in hand and wield power himself. He sat there now with his eyes downcast, the once snow-fair hair he had inherited from the King’s beloved “Gentle Jane” darkening to a ruddy brown more like that of his uncles, the battling Seymour brothers – fish-frigid but oh so clever Edward and jolly, good-time Tom – than the flaxen locks of his pallid mother or the fiery Tudor-red tresses of his famous sire. His fingers absently shredded the curly white plume that adorned his round black velvet cap, letting the pieces waft like snowflakes onto the exotic whirls and swirls of the luxurious carpet from faraway Turkey. He then abandoned the denuded shaft to pluck the luminous, shimmering Orient pearls from the brim, letting them fall as carelessly as if they were nothing more than pebbles to be picked up, pocketed, and no doubt sold by the servants. Like casting pearls before swine!

“Oh, Edward!” Henry wept and raged against the Fates. “The son I always wanted but not the king England needs!”

Catherine Parr rose from where she knelt at the foot of the bed and took a jewel-encrusted goblet from the table nearby and filled it from a pitcher of cold water. Gently cupping the back of her husband’s balding head, as if he were an infant grown to gigantic proportions, and lifting it from the pillows, she held the cup to his lips, thinking to cool his fever and thus remedy his distress. But not all the cool, sweet waters in the world could soothe Henry Tudor’s troubled spirit.

The black-velvet-clad sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, the rich silver and golden threads on their black damask kirtles and under-sleeves glimmering in the candlelight like metallic fish darting through muddy water, sat on either side of their little brother, leaning in protectively. But as they comforted him with kind, reassuring words and loving arms about his frail shoulders – the left a tad higher than the right due to the clumsy, frantic fingers of a nervous midwife and the difficulty of wresting him from his mother’s womb – their minds were far away, roving in the tumultuous past, turning the gilt-bordered, blood-spattered, angst-filled pages of the book of memory….

1

Mary

All I have ever wanted was to be loved, to find on this earth a love as true and everlasting as God’s.

As Father lay dying, I remembered a time when he had well and truly loved me; a time when he had called me the most valuable jewel in his kingdom, his most precious pearl, dearer than any diamond. Those were the days when he would burst through the door, like the bright golden sun imperiously brushing aside an ugly black rain cloud, and sweep me up into his arms and ask, “How fares my best sweetheart?” and kiss me and call me “the pearl of my world!” Easter of the year I turned five, upon a whim of his, to illustrate this, he had me dressed in a white gown, cap, and dainty little shoes so densely encrusted with pearls I seemed to be wearing nothing else, they were sewn so thick and close. And when I walked into the royal chapel between him and my mother, holding their hands, turning my head eagerly from left to right to smile up at them, I walked in love.

On my next birthday, my sixth, I awoke to find a garden of fragrant rosemary bushes, one for each year of my life, growing out of gilded pots, their branches spangled with golden tinsel and glowing mysteriously from within with circles of rosy pink, sunny yellow, sapphire blue, emerald green, and ruby red light, emanating, I discovered, from little lanterns with globes of coloured glass concealed inside. My father had created a veritable fairyland for me, peopled with beautiful fairies and evil imps, grotesque goblins and mischievous elves, leering trolls, playful pixies, crook-backed gnomes, and gossamer-winged sprites, and the Fairy Queen herself, flame-haired and majestic in emerald green, all made of sugar and marzipan in a triumph of confectioner’s art. I stood before them timid and unsure, hardly daring to move or breathe, in case they truly were real and might work some terrible magic upon me if I dared interfere with them, until Father laughed and bit the head off a hobgoblin to show me I had nothing to fear. And there were four gaily costumed dwarves, two little women and two little men, every seam, and even their tiny shoes and caps, sewn with rows of tiny tinkling gold bells, to cavort and dance and play with me. We joined hands and danced rings around the rosemary bushes until we grew dizzy and fell down laughing. And when I sat down to break my fast, Father took it upon himself to play the servant and wait upon me. When he tipped the flagon over my cup, golden coins poured out instead of breakfast ale and overflowed into my lap and spilled onto the floor where the dwarves gathered them up for me.

In those days we were very much a family and, to my child’s eyes, a happy family. Before I was of an age to sit at table and attend banquets and entertainments with them, Mother and Father used to come into my bedchamber every night to hear my prayers on their way to the Great Hall. How I loved seeing them in all their jewels and glittering finery standing side by side, smiling down at me, Father with his arm draped lovingly about Mother’s shoulders, both of them with love and pride shining in their eyes as they watched me kneel upon my velvet cushioned prie-dieu in my white nightgown and silk-beribboned cap, eyes closed, brow intently furrowed, hands devoutly clasped as I recited my nightly prayers. And when I was old enough to don my very own sparkling finery and go with them to the Great Hall, I cherished each and every shared smile, sentimental heart-touched tear, and merry peal of laughter as, together, we delighted in troupes of dancing dogs and acrobats, musicians, minstrels, morris dancers, storytellers, and ballad singers.

And we served God together. Faithful and devout, we attended Mass together every day in the royal chapel. My mother spent untold hours kneeling in her private chapel before a statue of the Blessed Virgin surrounded by candles, a hair shirt chafing her lily-white skin red and raw beneath her sombrely ornate gowns, and hunger gnawing at her belly as she persevered in fasting, begging Christ’s mother to intercede on her behalf so that her womb might quicken with the son my father desired above all else.

When the heretic Martin Luther published his vile and evil blasphemies, Father put pen to paper and wrote a book to refute them and defend the holy sacraments. When it was finished he had a copy bound in gold and sent a messenger to present it to the Pope, who, much impressed, declared it “a golden book both inside and out”, and dubbed Father “Defender of the Faith”. To celebrate this accolade, Father ordered all the pamphlets and books, the writings of Martin Luther that had been confiscated throughout the kingdom, assembled in the courtyard in a great heap. In a gown of black velvet and cloth-of-gold, with a black velvet cap trimmed with gold beads crowning my famous, fair marigold hair, I stood with Mother, also clad in black and gold, upon a balcony overlooking the courtyard, holding tight to her hand, and clasping a rosary of gold beads to my chest as I, always short-sighted, squinted down at the scene below. I felt such a rush of pride as Father, clad like Mother and I in black and gold, strode forth with a torch in his hand and set Luther’s lies ablaze. I watched proudly as the curling white plumes of smoke rose up, billowing, wafting, twirling and swirling, as they danced away on the breeze.

I also remember a very special day when I was dressed for a very special occasion in pomegranate-coloured velvet and cloth-of-gold encrusted with sparkling white diamonds, lustrous pearls from the Orient, regal purple amethysts, and wine-dark glistening garnets, with a matching black velvet hood covering my hair, caught up beneath it in a pearl-studded net of gold. I was being presented to the Ambassadors of my cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Though he was many years older than myself, it was Mother’s most dearly cherished desire that we would marry; she had always wanted a Spanish bridegroom for me and raised me as befitted a lady of Spain, and the Ambassadors had come to judge and consider my merits as a possible bride for Charles.

As I curtsied low before those distinguished gentlemen in their sombre black velvets and sharp-pointed beards like daggers made of varnished hair, suddenly the solemnity of the moment was shattered by Father’s boisterous laughter. He clapped his hands and called for music, then there he was, a jewel-encrusted giant sweeping his “best sweetheart” up in his strong, powerful arms, tossing me up high into the air, and catching me when I came down, skirts billowing, laughing and carefree, for all the world like a wood-cutter and his daughter instead of the King of England and his little princess.

“This girl never cries!” he boasted when Mother sat forward anxiously in her chair, a worried frown creasing her brow, and said, “My Lord, take care, you will frighten her!”

But I just laughed and threw my arms around his neck, his bristly red beard tickling my cheek, and begged for more.

The musicians struck up a lively measure, and he led me to the centre of the floor, took my tiny hand in his, and shouted that I was his favourite dancing partner, and never in all his years had he found a better one.

As the skipping, prancing steps of the dance took us past the Ambassadors, suddenly he ripped the hood and net from my hair and tossed them into their startled midst. He combed his fingers through the long, thick, rippling waves, then more gold than red on account of my youth – I was but nine years old at the time – and his pride and joy in me showed clear upon his face.

“What hair my sweetheart has!” he cried. “My Lords, I ask you, have you ever seen such hair?”

And indeed he spoke the truth. In my earliest years I had Mother’s Spanish gold hair lovingly united with Father’s Tudor red, blending beautifully into an orange-yellow shade that caused the people to fondly dub me “Princess Marigold”. “God bless our Princess Marigold!” they would shout whenever I rode past in a litter or barge or mounted sidesaddle upon my piebald pony, smiling and waving at them before reserved dignity replaced childish enthusiasm.

Though it may seem vain to say it, I had such beautiful hair in my youth, as true and shining an example as there ever was of why a woman’s tresses are called her crowning glory. But before my youth was fully past it began to thin and fade until its lustrous beauty and abundance were only a memory and I was glad to pin it up and hide it under a hood, inside a snood or net, or beneath a veil.

But oh how I treasured the memory of Father’s pride in me and my beautiful hair! The day he danced with me before the Ambassadors became one of my happiest memories.

I would never forget the way he swept me up in his arms and spun me round and round, my marigold hair flying out behind my head like a comet’s tail, as he danced me from one end of the Great Hall to the other.

I never thought the love he felt for me then would ever diminish or die. I thought my earthly father’s love, like our Heavenly Father’s love, was permanent, unchanging, and everlasting.

“This girl never cries!” Father had said. Little did he know I would make up for a childhood filled with unshed tears by crying whole oceans of them in later years, and that most of them would be spilled on account of him, the callousness and cruelty he would mete out to me in place of the love and affection he once gave so freely and unconditionally to me.

But that was yet to come, and in those early days I truly was a princess. I sat on my own little gilded and bejewelled throne, set upon a dais, and upholstered in purple velvet with a canopy of estate, dripping with gold fringe, above me, and a plump purple cushion below me to rest my feet upon. And I wore gowns of velvet, damask, and brocade, silk, satin, silver, and gold; I sparkled with a rainbow of gems, and snuggled in ermine and sable when I was cold; gloves of the finest Spanish leather sheathed my hands; I walked in slippers made of cushion-soft velvet embroidered with pearls, gems, or gilt thread, and when I rode, boots of Spanish leather with silken tassels encased my feet; and underneath my finery only the finest lawns and linens touched my skin. But it was not the prestige and finery I liked best; being my father’s daughter was what delighted my heart most. And during the bad years that followed the blissful ones, I used to think there was nothing I would not give to hear him call me “my best sweetheart” again.

Having no son to initiate into the manly pursuits, Father made do as best he could with me. He took me with him to the archery butts, and when I was nine he gave me my first hawk and taught me to fly her. We rode out at the head of a small retinue, me in my velvet habit, dyed the deep green of the forest, sidesaddle upon my piebald pony, the bells on my goshawk’s jesses jingling, and the white plume on my cap swaying. And Father, a giant among men, powerfully muscular yet so very graceful, astride his great chestnut stallion, clad in fine white linen and rich brown hunting leathers, with bursts of rainbow light blazing out from the ring of white diamonds that encircled the brim of his velvet cap, and the jaunty white plume that topped it bouncing in the breeze.

We were following our hawks when we came to a large ditch filled with muddy water so dark we could not discern the bottom. Father made a wager with one of his men that he could swing himself across it on a pole. But when he tried, the pole snapped beneath his weight, and Father fell with a great splash, headfirst into the murky water. His legs and arms flailed and thrashed the surface frantically, but his head never appeared; it was stuck fast, mired deep in the mud below.

Edmund Moody, Father’s squire, who would have given his life a hundred times over for him, did not hesitate. He dived in and worked to free my father’s head. I could not bear to stand there doing nothing but watching helplessly, praying and wringing my hands, fearing that my beloved father might drown, so I recklessly plunged in, my green velvet skirts billowing up about my waist, floating on the muddy water like a lily pad. As I went to assist Master Moody, the tenacious mud sucked at my boots so that every step was a battle, slowing me down and showing me how it must be holding Father’s head in a gluelike grip.

But through our diligent and determined efforts, Father was at last freed. Sputtering and gasping, coughing and gulping in mouthfuls of air, Father emerged and, leaning heavily between us, we helped him onto the grass, and he lay with his head in my lap as I tenderly cleaned the mud from his hair and face. An awed and humble cottager’s wife brought us pears, cheese, and nuts in her apron, and we sat in the sun and feasted upon them as if they were the finest banquet while the sun dried us. Father made a joke about how my skirts had floated about me like a lily pad and called me his lily. And when we returned to the palace he summoned a goldsmith and commissioned a special jewelled and enamelled ring for me to commemorate that day when I had helped save his life – a golden frog and a pink and white lily resting on a green lily pad. It was the greatest of my worldly treasures, and for years afterward a week scarcely passed when it did not grace my finger. Even when I did not wear it, I kept it safe in a little green velvet pouch upon my person so I would always know it was there with me, a proud and exquisite emblem of Father’s love for me.

Those were the happy days before the sad years of ignominy and disgrace, penury, indifference, and disdain, the callousness and cruelty he learned under the tutelage of The Great Whore, Anne Boleyn, the threats and veiled coercion, followed by a sort of uneasy tolerance, a truce, when he offered me a conditional love wherein I must betray my conscience, my most deeply cherished beliefs, and my own mother’s sainted memory, and capitulate where she herself had held firm, if I wanted to bask in the sun of his love again.

To my everlasting shame, though I would hate myself for it ever afterward, I gave in to their barrage of threats. The Duke of Norfolk himself took a menacing step toward me and informed me that if I were his daughter he would bash my head against the wall until it was as soft as a baked apple to cure me of my stubbornness. And haunted by accounts of those who had already died for their resistance, including Sir Thomas More and cartloads of nuns and monks, I signed the documents they laid before me. “Lady Mary’s Submission,” they called it. I signed and thus declared my mother’s marriage a sin, incestuous and unlawful in the sight of God and man, and myself the bastard spawn born of it. Even though my most trusted advisor, the Spanish Ambassador, urged me to sign and save myself, assuring me that a victim of force would be blameless in God’s sight, and that since I signed under duress, in fear for my very life, the Pope would grant me absolution, such assurances did not ease my conscience or assuage my guilt, and my body began to mirror my mind’s suffering. My stomach rebelled against all food, my hair began to fall out, and I suffered the agonies of the damned with megrims, monthly cramps, palpitations of the heart, and toothache, and before I was twenty I was known throughout Europe as “the most unhappy lady in Christendom”, and the tooth-drawer had wrenched out most of the teeth Father had once called “pretty as pearls”, leaving my face with a pinched, sunken expression and a close-mouthed smile that was purposefully tight-lipped. It was a miracle I survived, and I came wholeheartedly to believe that God had spared my life so that I might do important work in His name.

I betrayed everything I held sacred and dear just to walk in the sun of my father’s love again, but it was never the same, and that, I think, was my penance, my punishment. It wasn’t the old welcoming, all-embracing warmth that had enveloped me like a sable cloak on a cold winter’s day; it was a weak, wavering, watery-yellow sunbeam that only cast a faint buttery hue, a faltering wispy frail fairy-light of yellow, onto the snow on a bone-chilling day. Just a tantalizing little light of love that left me always yearning for more, like a morsel of food given to a starving man only inflames his appetite. It was never enough compared to what had been before. But when I signed I did not know this. I was full to overflowing with hope when, in a presence chamber packed with courtiers, I knelt humbly before my scowling, glowering father and kissed the wide square toe of his white velvet slipper, slashed through with blood-red satin, reminding me of all the blood he had spilled and that it was always in his power to take my life upon a moment’s fancy. After I kissed his shoe I sat up upon my knees, like a dog begging, my tear-filled eyes eager and beseeching, and told him earnestly that I would rather be a servant in his house than empress of the world and parted from him.

But there were many years of pain and humiliation that preceded my surrender and self-abasement.

For seven years, and against all the odds, The Great Whore led my father on a merry dance that made him the scandal and laughing stock of Europe and turned the world as I had known it upside down. She swept through my life as chaotic, destructive, merciless, and relentless as the ten plagues of Egypt and nothing would ever be the same again. Like a mastiff attacking a baited bear, she tore away all that I held dear. “All or Nothing” was her motto and she meant it. She took my father’s love away from me and worked her dark magic to transform it into hatred and mistrust; she broke my mother’s heart and banished her to die in brokenhearted disgrace in lonely, neglected exile; she took my title of “Princess” and my place as heiress to the throne away from me and gave it to her own red-haired bastard brat; she even took my house away, my beautiful Beaulieu, and gave it to the brother who would loyally let her lead him to the scaffold after his own wife revealed details of their incestuous romance. I remember her sitting on the arm of Father’s golden throne, with diamond hearts in her luxuriant black hair, worn unbound like a virgin as her vanity’s emblem, whispering lies into his ear, poisoning his mind against me, exacting a promise, because she knew how much it meant to me, that in his lifetime he would never allow me to marry lest my husband challenge the rights of the children she would bear him. I remember how she laughed and threw back her head as he reached up to caress her swan-slender neck, encircled by a necklace of ruby and diamond hearts. The rubies glistened like fresh blood in the candlelight. The sight made me shudder and I had to turn away.

Like the “Ash Girl” in the story my nurse used to tell me, who was made to be a servant to her stepsisters, I was made to serve as a nursemaid to the puking and squalling “Little Bastard” who had taken my place in our father’s heart and usurped my birthright, my title and inheritance.

Elizabeth. I saw her come into this world with a gush of blood between The Great Whore’s legs at the expense of the heart’s blood of my mother and myself. I was made to bear witness to her triumphant arrival as Anne Boleyn, even on her bed of pain, raised her head to gloat and torment me, the better to conceal her own disappointment at failing to keep the promise she had made to give Father a son. But Father was still so besotted with her that, though disappointed by the child’s sex, he forgave her.

To please Anne, Father had heralds parade through the corridors of Greenwich and announce that I was now a bastard and no longer to be addressed or acknowledged as Princess; Elizabeth was now England’s only princess. My servants were ordered to line up and Anne’s uncle, the Duke of Norfolk himself, walked up and down their ranks, ripping my blue and green badge from their liveries. And Anne’s father, Thomas Boleyn, announced that when they had been fashioned each would be given a badge of Elizabeth’s to replace mine, to show that they were now in her service. As I stood silently by and watched, my face burned with shame and each time another badge was torn away I felt as if I had been slapped.

Elizabeth. I should have hated her. But Christian charity would not allow me to hate an innocent child. No, that is not entirely true; my heart would not let me hate her. And no child should be held accountable or blamed for the sins of its mother, not even such a one as that infamous whore and Satan’s strumpet, Anne Boleyn.

At seventeen, the age I was when Elizabeth was born, I longed more than anything to be a wife and mother, and when I saw that scrunched-up, squalling, pink-faced bundle of ire, with the tufts of red hair feathering her scalp, my arms ached to hold her. I could barely contain myself; I had to almost sit on my hands to keep from reaching out and begging to hold her.

Even when I was stripped of all my beloved finery – even made to surrender the dear golden frog and enamelled lily pad ring Father had given me, and the little gold cross with a splinter of the True Cross inside it that had belonged first to my grandmother and then to my mother before she had given it to me on that oh so special sixth birthday – and forced to make do with a single plain black cloth gown and white linen apron, and to tuck my hair up under a plain white cap just like a common maidservant, and made to sleep in a mean little room in the servants’ attic, cramped and damp, with stale air and a ceiling so low, even petite as I was I could not stand up straight, still I could not hate Elizabeth. Even when I sickened and wasted away to skin and bones for want of food – I dared not eat lest The Great Whore send one of her lackeys to poison me – I could not hate, blame, or resent Elizabeth. Not even when I was wakened from a deep, exhausted sleep and brought in to change her shit-soiled napkins, I did not protest and wrinkle my nose up and turn away fastidiously, but humbly bent to the task and did what was required of me. And when her teeth started to come in – oh what pain those dainty pearls brought her! – I went without sleep and walked the floors all night with her in my arms, crooning the Spanish lullabies my mother had sung to me. Even when I was forced to walk in the dust or trudge through the mud alongside, but always three steps behind, while she rode in a sumptuous gilt and velvet-cushioned litter, dressed in splendid little gowns encrusted with embroidery, jewels, and pearls, while I went threadbare and wore the soles off my shoes as I stumbled and stubbed my toes over ruts and rocks or got mired in the mud, still my heart was filled with love for Elizabeth.

I relished each opportunity to bathe, feed, and dress her, to change her soiled napkins, rub salve onto her sore gums, tuck her into bed, coax and encourage her first steps as I held on to her leading strings, promising never to let go, and the wonderful afternoons when I was allowed to lead her around the courtyard on her first pony. And when she spoke her first word, a babyish rendition of my name – “Mare-ee” – my heart felt as if it had leapt over the moon. I loved Elizabeth; her leading strings were tied to my heart. Serving her was never the ordeal they intended it to be, for I knew who I was – I was a princess in disguise, just like in a fairy tale, and someday the truth would be revealed and all that was lost restored to me.

Sometimes I told myself I was practising for the day when I would be married and a mother myself, but I was also lying to myself as with each year my hopes and dreams, like sands from an hourglass, slipped further away from me even as I strained and tried with all my might to hold on to them until I felt all was lost and imagined I was watering their grave with my tears. For what man would have me? My father had declared me a bastard when his minion, the so-called Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, dissolved his marriage to my mother. And though I dreamed, I never really dared hope that someday someone would fall in love with me. Love was the stuff of songs and stories and, for me, as elusive as a unicorn. Sometimes, I know better than any who has ever walked this earth, no matter how much you want something, you still cannot have it.

And the promise of beauty I had, as a child, possessed had failed to ripen into reality; it had deserted me in my years of grief, fear, and peril. My first grey hair sounded the death knell to my last lingering hope that I might someday attract a suitor. I was seven teen, and a scullery maid who was secretly sympathetic to my plight was brushing out my hair before I retired to my comfortless cot for another miserable night. She gave a little gasp and stopped suddenly, and I turned to see a stricken, sad look in her eyes. Mutely, she brought my hair round over my shoulder so I could see the strand of grey, standing out starkly like a silver thread embroidered on auburn silk. I nodded resignedly. What else could I do but accept it? “Bleached by sorrow,” I sighed, and thanked her for her kind ministrations and went to my bed, but secretly, after I had blown the candle out, with the thin coverlet pulled up over my head, I cried myself to sleep as I said farewell to and buried one more dream.

But I had my faith to keep me strong. My mother always inspired great loyalty and love in those who knew her, thus she was able to find someone willing to take the risk and carry secret words of comfort to me. “Trust in God and keep faith in Him and the Holy Virgin and you will never be alone,” she lovingly counselled me. “Even though we are divided in body, remember whenever you kneel to say your prayers, I will always be right there beside you in spirit. Faith in Our Lord and the Blessed Virgin are the ties that bind. Always remember that, my darling daughter. And God never gives us more than we can bear. Sometimes He tests us, to show us how strong we really are, and that, as we have faith in Him, so too does He have faith in us, and wants us to have faith in ourselves.”

I was holding Elizabeth, then aged three, on May 19, 1536, when the Tower guns boomed to let Father, and all of England, know that he was free and the spell of the witch-whore had been broken. Elizabeth was now motherless, just like me. There we sat, a faded spinster in a threadbare black gown grown thin and shiny at the elbows and ragged at the hem, with a maid’s plain white cap to hide her thinning hair, and a porridge-stained apron, and a vibrant, precocious toddler in pearl-embellished sunset-orange and gold brocade to complement the flame-bright curls tumbling from beneath a cap lovingly embroidered in golden threads by The Great Whore who had given life to her.

Now it was Elizabeth’s turn to be a disgraced bastard accounted of no importance. And as fast as she was growing, soon she too would be in shabby clothes. Father wanted to forget, so I doubted money would be provided to keep her in fine array, so soon it would be goodbye to brocade and pearls. Our mothers were dead, mine a saint gone straight to Heaven and hers a whore and a witch gone straight to Hell – and our father had turned his back on us and called down the winter’s gloom and chill to replace the warm sun of the love he had once given in turn to each of us. Now all we had was each other.

I wasn’t with my mother when she died. When her body was laid open by the embalmers they found her heart had turned quite black and a hideous growth embraced it. I have often wondered whether it was some slow-acting poison administered by one of The Great Whore’s minions or a broken heart pining for her Henry that killed her. She died declaring that her eyes desired my father above all things.

On the day my mother was entombed, Anne Boleyn’s doom was sealed when she miscarried the son who would have been her saviour. Father’s eye had already lighted on wholesome and pure, sweet Jane Seymour, a plain and pallid country buttercup to The Boleyn Whore’s bold and tempestuous red rose. Her earnest simplicity and genuine modesty had completely won his heart, and it was only a matter of time; we all knew The Great Whore’s days were numbered, and the number was not a great one. I saw it as divine retribution, an eye for an eye, a life for a life. Anne Boleyn, whether some lackey in her employ had administered a killing dose or not, was responsible for my mother’s death, for which she dressed in sun-bright yellow to celebrate and insisted that Father do the same, thus, it was only fitting that her own life be cut short and a truly worthy woman take her place at Father’s side.

As I sat there rocking Elizabeth, hugging her tight against my breast, I remembered the last time I saw my mother. Dressed for travel, in the courtyard, with her litter and a disrespectfully small entourage awaiting nearby, she knelt and pressed into my hands a little book of the letters of Saint Jerome and her own treasured ivory rosary, which had belonged to her own mother, the beads grown creamy with age and the caressing fingers of these two strong and devout Spanish queens.

“God only tests those He cherishes, in order to strengthen them and their virtues,” she said to me, and then she embraced and kissed me. I never saw her again.

It was Jane Seymour who would work a miracle and persuade Father to see me. And as I knelt to kiss his foot, I saw from the corner of my eye her rust-red velvet gown and gold and black lattice-patterned kirtle as she stood meekly beside him. It was she who nodded encouragingly and looked at him with pleading eyes as I knelt there with bated breath awaiting my fate.

And then, after a tense glowering silence that seemed to hover like an executioner’s axe above my head, he gave his hand to me, and I saw upon his finger the great ruby known as the Regal of France, famous for its brilliance that was said to light up even the dark, that had once adorned the now desecrated and demolished shrine of Thomas Becket at Canterbury. Father had had it made into a ring, and for the rest of his life would wear it as a symbol of his mastery over the Church, flaunting the fact that he had kicked the Pope out of England and had enriched himself with “Papist spoils” when the monasteries were dissolved and the lands parcelled out, sold or gifted to favoured courtiers, and the monks and nuns who had done so much good, dispensing alms, succouring the poor, and tending the sick, were turned out to become beggars and vagabonds themselves. I recoiled, sickened, at the sight of that glowing blood-red ring and feared I would vomit all over his feet; it took all of my will to take his hand and kiss it. I knew my submission was yet another betrayal of God, my mother, and our beliefs.

But I did it. And his face broke out in a triumphant smile. He raised me to my feet, embraced me, and kissed me. And, at his urging, Jane Seymour did the same. I was allowed to sit on the dais, on the top step, at their feet, and the woman Father called his “Gentle Jane” soon became one of the dearest friends I have ever had. She did much to further my cause. In time, all my manor houses and lands were restored to me, the jewels that had been taken from me were returned, along with some that had belonged to my mother that The Great Whore had stolen, my old servants came back, and Father personally selected fine horses for me. I was given pets, Italian greyhounds and a parrot, and even for my first birthday after my return to favour, a female fool to entertain me and enliven the dull hours, and Father also chose a talented band of musicians to join my household. Queen Jane helped me with my wardrobe; old gowns were refurbished, and many new ones ordered. We sat together for hours scrutinizing the wares the London mercers laid before us. And she gave me a diamond ring from her own finger that I would forever cherish.

She had a generous heart and was kind to everyone, even Elizabeth. Treading with great delicacy and care, she engineered Elizabeth’s return to court and had her too-short-even-with-the-hems-turned-down bursting-at-the-seams gowns and pinching, parchment-thin-soled shoes replaced. What fun we had dressing her, each of us pretending that our deeply cherished dream of motherhood had come true and she was our very own little girl to clothe and choose pretty things for.

When I thanked Queen Jane for her kindness, she said to me: “Verily, I could not do otherwise. When I look at her I think if I had a daughter and some misfortune were to befall me, and I could not be there to see her grow up, I would hope that my successor, whoever she was, would be kind to her. There but for the grace of God, My Lady Mary, there but for the grace …”

When she was with child and craving cucumbers and quails, Father took care of the birds, sending as far away as Calais for them, while I sent her baskets brimming with cucumbers from my own country gardens.

I wept an ocean when she died. Even though her death gave Father his most heartfelt desire – a son, my brother, Edward – I still keenly felt her loss. Because of her kind heart, I was a princess again in all but name.

Other wives followed, but none stayed very long. And in between queens I was the first lady of the land, privileged to sit at Father’s side, presiding over the court, with everyone bowing, smiling, and deferring to me, and there was even occasionally talk that a marriage might be arranged for me, but, alas, nothing ever came of that.

After Jane Seymour came the Lady Anne of Cleves, a German Protestant princess, a heretic, but a merry soul with a heart of gold. One could not help liking her, even though the cleanliness and odours of her person and the dowdiness of her clothes left much to be desired. But Father could not stomach to lie with her and she obligingly, no doubt fearing the headsman’s axe if she did not graciously acquiesce, exchanged the role of queen for that of adopted sister and a substantial income that would allow her to lead the life of an independent lady of means.

And after Anne came the one people chuckled behind their hands about and called “the old man’s folly”, pert and wanton Catherine Howard with only fifteen years to Father’s fifty. I felt so embarrassed for him! I marvelled that he could not see how she demeaned his majesty. She made him the butt of jests and remarks that ran the gamut from pitying to lewd. She meant to be kind, I am sure, but she could not curb her exuberance; she did not under stand that being a queen meant one must comport oneself with dignity. Though I was some years older than she, and to call her my stepmother felt supremely awkward, she tried to befriend me, being overfamiliar as though she were my own sister, one with whom I had grown up in close intimacy, sharing everything. She would brazenly and openly discuss the most intimate things with no regard for modesty or propriety.

She could not believe that I had reached the ripe old age of twenty-four without ever having had a sweetheart, and would prod me incessantly, over and over again, asking incredulously, “You mean you never had a sweetheart, never?” And when I answered, alas, God had not so deemed to bless me, she embraced me and bemoaned the tragedy of my fate, then, blinking away her tears and tossing back her auburn curls, determinedly said we must do something to remedy it.

She arranged a masque for my birthday wherein a number of particularly handsome young men, whom she had chosen herself, were costumed as various flowers, dressed in shimmering satins and silks of the proper colours festooned with lace and embroideries and intricate silk renditions of the blooms they had been chosen to represent.

“We need a little springtime even in the chill of February!” the hoydenish young queen declared as she whooped and kicked up her heels and bade this garden of living posies to encircle and dance around me.

I remember there was a graceful pink gillyflower, a deep red rose who was rather bold, a haughty regal violet, a jaunty daffodil, a bluebell whose costume was cunningly devised to include tiny tinkling bells, a marigold whose tawny locks brought back memories of my youth, a flamboyant heart’s-ease pansy, a perky pink, a bashful buttercup, a profusely blossoming lavender, a rather indecent goldenrod who brushed me from behind to draw my attention to the prominent golden bloom sprouting from his loins, and a demure – by comparison to the rest – daisy. As they danced around me they each offered me silken flowers taken from their attire and sang, “Choose me, pretty maiden, do!”

Roses of vivid pink embarrassment bloomed in my cheeks and I desired nothing more than to break the dancing ring moving around me and escape to the privacy of my bedchamber. I disliked being the centre of such attentions, and there was a nagging suspicion at the heart of me that they were mocking and making cruel sport of me, the pathetic Lady Mary who was no longer young and had never been pretty like the Queen. Katherine crept up behind me and tied a kerchief over my eyes and spun me round and round until I staggered dizzily and feared I might disgrace myself by being sick, then gave me a shove into the arms of the nearest gentle man.

“Ah, heart’s-ease, that brings back memories, does it not, my dear Derham?” she teasingly addressed the vividly costumed gentleman who held me in his arms and had just removed my blindfold so I could see him smiling down at me with a set of very fine, even white teeth.

She drew me aside for a moment before we paired off for dancing and whispered wicked but kindly meant words in my ear, telling me that if I were so minded to meddle with a man, she knew of ways to prevent conception. I was appalled that she would speak of such, and even more so that she would possess such knowledge, and with flaming cheeks I pulled away from her and fled, forsaking the chance to dance with Master Derham.

Time would later disclose that, despite her youth, Catherine Howard had been a rather enthusiastic gardener herself, and that of the bevy of handsome fellows who had danced around me that night, two of them were known to have been her lovers. Francis Derham was purposefully costumed as heart’s-ease as a reminder of a silken flower he had once given his common-law wife – the Queen – a fact unbeknownst to Father, who called that wanton little guttersnipe his “Rose Without a Thorn”. And even at that time she was dallying with the daffodil – Thomas Culpepper, Father’s favourite bodyservant, who so tenderly ministered to his poor, sore and ulcerated legs.

She gave me a gold pomander ball studded with turquoises and rubies for my birthday, but I made a point of losing it. I wanted nothing from that foolish girl and hoped that perhaps some poor soul might find it and benefit from the sale of so costly a bauble.

It was only a matter of time before the truth came out and she died on the scaffold for her sins and Father was plunged into a deep, dark depression from which I feared he would never emerge.

But emerge he did, to take a sixth and final wife, the one who would nurse and care for him for the remainder of his life. He began and ended his married life with a Catherine. Both Catherine of Aragon and Catherine Parr were kind, clever, strong, and capable women. And though I liked her well, and she did much for my sister and me, seeing that Elizabeth received a formidable education every bit as good as that given to our brother, and persuading Father to reinstate us in the succession so we could both be called “Princess” again, still I mistrusted Kate on account of her Reformist beliefs. Though she kept it discreetly veiled, she was in truth a Protestant, a heretic, and encouraged my brother and sister to follow this path, which would lead them away from the true religion.

This made me both fearful and sad. I wanted to right the wrongs Father had wrought at The Great Whore’s instigation. I wanted to go back in time to a place of greater safety, to the tranquillity and traditions of my childhood, and the indescribably blissful feeling of rightness and a well-ordered world. I remembered the love, the peace, the sense of security and serenity I had felt when I walked, dressed in pearls, between my parents, who loved each other and loved me, and went hand in hand with them to kneel and worship God, to witness the miracle when the priest held the Host aloft and the bread became the body of Jesus Christ, our Saviour. There was nothing better and nothing else like it in the world, and I wanted my siblings to know and share it; I wanted faith to unite us, not tear us apart. The comfort of the Latin litanies, the adoring hymns writ to praise Him, the Miracle of the Mass, the Elevation of the Host, the comforting clickety-clack of rosary beads moving smooth and cool beneath devout fingers, the swinging censers filling the chapel with fragrant incense, the sprinkling of holy water, the flickering candles that reminded us that God is the light of the world, the crucifixes and statues, the tapestries and jewel-hued stained-glass windows depicting scenes from the Bible, the embroidered altar cloths, the golden chalices, the embroidered vestments the priests wore, the beautiful things offered up to worship, glorify, and adore God and His saints and the Blessed Virgin, and the relics and shrines and the miracles they wrought: the blind made to see, and the lame to walk. I wanted my siblings to behold, marvel, and adore all these sacred things. And the knowledge, and the comfort it gave, that all who believed and followed the true faith walked with God, and walked in love, and never walked alone. More than anything, I wanted to give this special and most precious gift, this beautiful and blissful serene sense of well-being and peace, to my siblings and every other man, woman, and child who lived and breathed, to restore it to the people of England from whom it had been violently and most cruelly taken away. And as I sat keeping vigil at Father’s deathbed, I knew then that this was my divinely appointed mission. I was ready and God would not find me wanting; I would dedicate my life to it.

2

Elizabeth

Nothing lasts forever, and everyone says “goodbye”, even if they don’t actually say it because they don’t have the chance or choose not to out of cruelty, cowardice, or spite; it is not a question of “if”, it is only a matter of “when”. L’amaro e il dolce – the bitter and the sweet. Life is not a banquet; we cannot always pick and choose of which dishes we wish to partake; we have to take the bitter and the sweet, the bland and the savoury, the delicious and the detestable.

Sage? Philosophical? Poetic? Lofty? Call them what you will. These thoughts have often run like a raging river through my life. As my father lay dying they crashed violently against the rocks of my mind until I thought the pain would knock me to the floor, gasping and clutching my head in the throes of a violent megrim. He had, like a river himself, mighty and majestic, beautiful and horrible, tranquil or terrifying, the power to destroy any who dared cross him, sweeping them aside or pulling them down to drown. When I was a little girl I thought he was invincible, but by thirteen I was old enough to understand that Time and Death conquer all that live; kings are no exception to the rule, merely mortals God infuses with a little of His divinity and power. A crown is a God-given gift, and the one to whom it is given wields the power that comes with it for the good of all, not just for personal wealth and glory.

I could still remember a time before the very mention of my name, let alone a glimpse of me, was enough to make my father roar and lash out like a wounded lion. For the first three years of my life I was adored, a true princess, in title, and in the way others treated me, with bows and flattery and words spoken in soft, deferential tones.

I vividly remember a day when all the court was dressed in sunny yellow, all was jubilation and celebration, but I couldn’t under stand why. When I asked her, my lady-governess said, “No, My Lady Princess, today is not a holiday,” but would not say more and sternly forbade me to ask my parents. I too was dressed in a gown of gaudy yellow, sewn all over with golden threads and spark ling yellow gems like miniature suns themselves that seemed to wink mischievously at me whenever the light struck them. I loved watching the big round yellow jewels set in golden suns on the toes of my shoes peep out and flash and wink at me with every step I took so that my lady-governess had to scold me to walk properly like a princess and hold myself erect instead of stooped over like a hunchback as she escorted me to the Great Hall where my great golden giant of a father, as big and bright as the sun itself he seemed to me then, swept me up onto his shoulder and paraded me about, showing me off to all his court.

My mother was there too, her belly bulging round like a ball beneath the sunshine-yellow brocade of her gown. My father smiled and patted her stomach and said this, at long last, would be the Tudor sun the soothsayers had predicted would come to shine over England.

“It was supposed to be you, Bess,” he smilingly chided me. “My son has certainly taken his time in coming, but he is well worth waiting for.”

He patted my mother’s stomach again. “Herein sleeps your brother, Bess, England’s next king. Guard him well, Madame, guard him well,” he told my mother, and though the words were said in a laughing, jocular tone there was no laughter in his eyes; they were as hard as blue marble. And there was fear in hers when she heard them, racing like a frightened animal trapped in a room it yearns to flee, running frantically from end to end, across and back, up and down, even though it knows there is no escape. Though she tried to hide it behind her smile I saw the fear full plain even though I did not understand it at the time.

Then we were off again, parading round the room. My father tore the little yellow cap from my head and tossed it high into the air.

“Take off that cap and show the world that Tudor-red hair, Bess, my red-haired brat!”

And I shook my head hard, shaking out my curls to show them all that I was Great Harry’s red-haired brat and proud of it.

Even the marzipan was gilded that day and he let me eat all I wanted. Then a big yellow dragon came prancing in, all trimmed with red, gold, and green, with the players’ dancing legs in motley-coloured hose with bells on their toes peeking out from beneath the swaying yellow silk and gilded and painted body. But it was no ordinary dragon like I had seen at other revels. Instead of a fearsome, toothy gaping mouth and menacing red eyes, its painted papier-mâché face was a woman’s, sadly serene like the face of Our Lord’s mother, the face of a woman who would feel deeply the sorrows of the world and feel its weight profoundly perched upon her shoulders. I heard someone say her name was Katherine. I didn’t know it then, I was too little to understand, that it was my sister Mary’s mother, Catherine of Aragon, the proud princess from Spain who had died vowing that her eyes desired my father above all things. Instead of mourning a strong and valiant woman, who had been despite her petite stature a tower of strength and conviction, we were celebrating her demise by eating gilded marzipan, laughing, dancing, and cutting capers, while dressed in the brightest gaudy yellow imaginable. Years later when I discovered the truth about that day I felt sick; every time I thought of it after that I wanted to vomit up all the marzipan I had eaten that day even though it had all happened years ago.

My father swept me up and bounded over to the dragon. He drew his sword and gave me the jewelled dagger from his belt.

“Come on, Bess, let’s slay this dragon!” he cried, and laughing, we both struck out at the dancing, capering beast until it fell with a great groan onto the floor, sprawling conquered at our feet.

“That’s my girl!” He hugged me close and kissed my cheek, and buried his face in my bright red curls. “My Bess is as brave as any boy!” he declared. Then he threw me up into the air and caught me when I came down, my yellow skirts billowing like a buttercup about me. “Praise be to God,” he cried as he spun us round and round. “The old harridan is dead and we are free from all threat of war! The Emperor Charles can kiss my arse!” he shouted, causing all the court to roar and rock with laughter. And I laughed too even though I did not understand.

But I wasn’t just Great Harry’s red-haired brat; I was Anne Boleyn’s daughter too. I have seen her portrait hidden away in musty palace attics, and when I look at myself in the mirror, only my flame-red hair, and the milk-pale skin that goes with it, are Tudor. All the rest of me is Anne Boleyn – the shape of my face, my dark eyes and their shape, my nose, my lips, my long-fingered musician’s hands, even my long, slender neck. That is why, I think, for so many years my father could not stand the sight of me, and even after I was welcomed, albeit reluctantly at first, back to court, I would catch him watching me, and there would be something in his eyes, as if he were a man who had just seen a ghost. I was the living, breathing shade of someone he had loved enough to change the world to wed and then hated enough to kill; in my parents’ marriage the pendulum swung from love to hate without the middle ground of indifference in between. I think that was also why I had the ability to so easily provoke his rage, even when I did not mean to, thus giving him an excuse, when the sight of Anne Boleyn’s living legacy became too much for him, to send me away from court, back to Hatfield.

“Back to Hatfield” was a phrase I heard many times throughout my childhood, spoken morosely by me, my lady-governess, or stepmother of the moment, or in a thundering roaring red-black rage by my father.

I’m not supposed to remember her, but I do. Everyone thought I was so young that I would forget. Most of my memories are blurred and fleeting, the kind where I strain and strive to hold on to them and bring them into sharper focus but, alas, I cannot. It is like gazing at one’s reflection upon the surface of a still, dark blue-black pool onto which someone then abruptly drops a stone, causing the image to break and blur. But there is one day I remember very well, though some of the details are lost or hazy. I cannot recall it moment by moment, word by word, but what I do remember is vividly crisp and clear, etched diamond-sharp into my memory.

A spring day in the garden at Greenwich, my mother was dressed all in black satin, and her hair, long, thick, and straight, hung all the way down to her knees like a shimmering, glossy cloak of ink-black silk. She knelt and held out her arms to me, and I toddled into them, a baby still uncertain on my feet, learning to walk like a lady in a stiff brocade court gown, leather stays, and petticoats, with pearls edging my square-cut bodice “just like Maman!” I crowed happily when I noticed the similarity.

She laughed and swept me up into her arms and spun round and round. Suddenly she stopped, looking up at the window above, where my father stood frowning down at us, his face dark and dangerous, like a thundercloud. Even from far away I felt the heat of his anger. I whimpered and started to cry, the murderous intensity of his gaze having struck such terror into my little heart. And in my mother’s eyes … a wild, hunted look, like a doe fleeing from a huntsman and a pack of hounds. In later years, when I first heard the poem by Thomas Wyatt, the poet who was said to have loved her, in which he likened her to a hunted deer, I would be catapulted back to that moment and the look in her eyes, and see my father as a mighty huntsman poised to strike the killing blow.

“Never surrender!” my mother said to me that day, an adamant, intense, ferocity endowing each word. “Be mistress of your own fate, Elizabeth, and let no man be your master!”

Uncle George, her brother, was waiting for her. She beckoned to my lady-governess and set me down and went to join him. He put his arms around her and she laid her head upon his shoulder, and leaned welcomingly into him as they walked away. I never saw her again.

Then there came a day when I heard the Tower guns boom, rattling the diamond-paned glass in the windows like thunder. I was sitting on my sister Mary’s lap. She hugged me close and kissed my brow.

“We are both bastards now, poppet,” she whispered, and told me that my mother was dead, but I didn’t understand. Mary shook her head and refused to say more. “Not now, poppet, not now; later, when you are old enough to understand.” Then she began to sing a Spanish lullaby as she rocked me on her lap.

But I knew something was very wrong, I felt it in my bones, and when the servants started addressing me as “My Lady Elizabeth” instead of “My Lady Princess”, that confirmed my suspicions that something was very wrong indeed. And when they thought I was beyond hearing, some even referred to me as “The Little Bastard”, though when I asked what that word meant, faces flushed and voices stammered and the subject was hastily changed or I was given candy or cake or offered a song or a story or a new doll to distract me.

My world had changed overnight but I could not understand why and no one would tell me. “Where is my mother?” I asked over and over and over again, but all those about me would say, with averted eyes, was that she was gone and I must forget her and never mention her again. She never came to visit me any more, when she used to come so often, and the gifts of pretty caps and dresses stopped, and when I outgrew those I had there were lengthy delays before other garments, nowhere near as fine and not crafted from a mother’s love, finally came to replace them. I used to feel her love for me in every stitch, but now that was gone; these new clothes were made by a stranger’s hands. I didn’t understand it; did this mean she no longer loved me? And there were no more of the music lessons where either she or Uncle George – and where was he? – would take me on their lap and guide my fingers over the strings. And she had only just begun teaching me to dance. Where was she? Why did she not come to visit me any more? Why wouldn’t anyone tell me?

Then one day I heard the chambermaids gossiping as they were making my bed. I had come back to get the pretty doll, the last one she had given me, in a gown made from scraps left from one of her very own dresses, its bodice and French hood trimmed with pearls just like hers. I stood there silent and still, with tears running down my face, unbeknownst to them, and heard it all. When they told how the French executioner – imported from Calais as a token of the great love my father had once felt for her – had struck off her head in one swift stroke, I screamed and ran at them, kicking and biting, pummelling them with my tiny fists, and scratching them with my little fingernails. The physician had to give me something to quiet me. That was the last time I let my emotions get the better of me; it was also the last time I mentioned my mother. I put my doll away, at the bottom of a chest, tenderly and lovingly wrapped in a length of red silk with a lavender and rose petal sachet, and vowed never to surrender and never to forget. I would never give any man the power to act as a living god and ordain my fate – life or death at his sufferance or fancy. Never surrender! I burned those words into my brain and engraved them on my heart.

Afterwards, a parade of stepmothers passed fleetingly through my life. Most had pity in their eyes when they looked at me, and tried, though it was not their fault, to atone for what my father had done, and give me their best imitation of a mother’s love.

First pale, prim Jane Seymour, whose shyness made her seem cold and aloof. She died giving my father the son he had always longed for. When Mary took my hand and led me in to see our new little brother, lying in his golden cradle, bundled against the cold in purple velvet and ermine, Jane Seymour lay as listless and quiet as a corpse upon her bed, as still and white as a marble tomb effigy. Her skin looked so like wax I wondered that she did not melt; the heat from the fire was such that pearls of sweat beaded my own brow and trickled down my back. I was four years old then and fully understood what death meant. And in that moment my mind forged a new link in the chain between surrender, marriage, and death – childbirth. It was another peril that came when a woman surrendered and put her life in a man’s hands.

When Mary and I walked in the funeral procession, two of twenty-nine slow and solemn ladies – one for each year of Jane Seymour’s life – with bowed heads and hands clasped around tall, flickering white tapers, all of us clad in the simple, stark death-black dresses and snow-white hoods that meant the deceased had died in childbirth, I vowed that I would never marry. Later, when I told her, Mary shook her head and scoffed at this childish nonsense, hugging me close and promising that I would forget all about this foolish fancy when I was old enough to understand what being a wife and mother meant; it was something that every woman wanted. I bit my tongue and kept my own counsel, but I knew that my conviction would never waver; God would be the only man to ever have the power of life and death over me. And as I knelt in chapel before Jane Seymour’s catafalque, I looked up at the cross and swore it as a vow, a pact between God and myself. He would be my heavenly master and I would always bow to His will, but I would have no earthly master force his will upon me.

Then came jolly German Anne of Cleves, always pink-cheeked and smiling, a platter of marzipan and candied fruits, like edible jewels, always within reach. She even wore a comfit box on a jewelled chain about her waist so that she would never be without her sweets. I helped her with her English and she taught me German, and was the soul of patience when helping me with my much hated sewing. But I had no sooner learned to care for her than she was gone, supplanted by flighty, foolish, vain, but oh so beautiful Catherine Howard.

I was amazed to learn that she was but a few years older than me; I was seven and she was a tender fifteen to my father’s half century when they married. When I heard that she was my mother’s cousin I was so excited and eager to meet her, I bobbed on my toes like an ill-bred peasant child, bursting with impatience and craning my neck to catch a glimpse of her. Yet when at last I stood before her I looked in vain for any resemblance to my slim, elegant mother in that plump-breasted, auburn-haired, green-eyed, pouty cherry-lipped little nymph whom my father called his “Rose Without a Thorn” in token of what he saw as her pure, untrammelled innocence. Though she was indeed beautiful, she had none of my mother’s elegance, intelligence, and sophistication; she was more like an illiterate country bumpkin dressed up in silks and satins. And though the court looked askance at her impetuous, impulsive ways, my father adored her.

I remember once, one rare occasion when I was allowed to stay up as late as I wished for some court celebration – “Oh do let her!” my flighty young stepmother implored, and my father was so besotted he could not resist her. As the dawn broke, Catherine Howard suddenly tore off her shoes and stockings, flinging them aside with careless abandon, not caring where they fell or whether the servants pocketed the pearls and diamonds that trimmed the dainty white velvet slippers, and ran out onto the lawn, like a great length of green velvet spangled with diamonds spread out by an eager London mercer, to dance in the dew in her bare feet, reveling in the feel of the blades of grass tickling her naked soles and tiny pink toes. She threw back her head and laughed and laughed, a silly, giddy girl taking joy in life’s simple pleasures, twirling dizzily round and round, lifting her pearl-white skirts higher and higher, much more so than was proper, as she spun around, while my father slapped his thigh and roared with laughter at her antics.

“Come on, join me!” she cried, and some of the more daring ladies shed their shoes and stockings and ran out to dance with her, uttering delighted, startled little shrieks and piglet-squeals at the chilly nip of the dew on their naked toes.

Beside me, my sister Mary gasped, appalled, and looked fit to fall down dead of apoplexy when our stepmother’s swirling white skirts rose high enough to give a glimpse of plump dimpled pink-ivory buttocks, but my father clapped his hands and laughed all the harder.

Dressed most often in virgin white dripping with diamonds and pearls so that she looked like an Ice Queen, my father’s “Rose Without a Thorn” would sit, stroking her silky-haired spaniel or a big fluffy white cat, or idly twirling her auburn curls around her fingers, and daintily nibbling sweetmeats or languorously trailing her finger through some cream-slathered dish and lingeringly sucking it off, always appearing distant and bored, yawning and indolent, unless there was a handsome gallant nearby whom she could bat her eyelashes at and exchange coy, flirtatious banter with. Children and female company often seemed to bore her, though she was always kind to me. The only time she seemed to ever really stir herself was to dance, and oh how she loved to do that, artfully swirling about, high-spirited, young, and carefree, as she lifted her skirts high to show off her legs and garters, pretending it was an act of exuberant mischance when in truth it was carefully choreographed and practised for hours before a mirror in the privacy of her bedchamber. I knew this for a fact, for she had offered to teach Mary and me, but Mary had gasped in horror and dragged me out the door as fast as if we were fleeing the flames of Hell.

I noticed that a certain courtier, a particularly handsome fellow called Thomas Culpepper, had a most curious effect on her. Whenever he was near, a flush would blossom rose-red in Catherine’s cheeks and her bosom would begin to heave beneath the tight-laced, low-cut bodice of her gown until I feared her laces would burst and her breasts spring out, and until he left her presence she would act more distracted and empty-headed than ever. Once when I sat embroidering beside her and Master Culpepper came in, she bade me go and play in the garden as it was such a lovely day when in truth it was pouring down rain.

Then she too was gone, like a butterfly fated to live only a season – her head stricken off just like my mother’s, only by an English headsman’s weighty, cumbersome axe; there was no French executioner with his sleek and graceful sword for my father’s “Rose Without a Thorn”. And Master Culpepper’s head, I heard, and that of another man, one Francis Derham, adorned spikes on London Bridge, to be pecked and picked clean by the voracious ravens. And people began to tell tales about Catherine’s white-gowned ghost running along the corridors of Hampton Court, uttering bloodcurdling screams, begging and pleading for mercy, pounding futilely on the chapel door, as she had done the day my father turned his back and a deaf ear on her.

And I saw again how men and sex and marriage had destroyed another woman who was close to me, in blood if not in affection. My father, acting as a vengeful god on earth, had ordained her death, showing none of the mercy or forgiveness our Heavenly Father might have vouchsafed wanton little Catherine Howard.

“I will never marry,” I said to my best friend, Robert Dudley, whom I called Robin, who laughed at me and said he would remind me of my words when he danced with me on my wed-ding day.

Then, like the answer to a prayer, came Catherine Parr. Kind Kate, capable Kate, we all called her, a mature, twice-widowed woman with the gift of making everything all right, of solving every problem and soothing every hurt. Fearlessly, she went like an angel into the lion’s den and tended my father in his declining years. Never once did her nose wrinkle or disgust show upon her face when she tended his putrid, pus-seeping leg, applying herbal poultices of her own concoction and changing the bandages with comforting and efficient hands. Though it was an open secret that she harboured a strong sympathy for the Protestant religion, deemed heretical by many, including my staunchly Catholic sister, she won Mary’s affection and became a loyal friend and loving stepmother to her. And to me … She was my saviour! She did more than any other to restore me to my father’s good graces. And she took a personal interest in the development of my mind; she was passionate about education for girls, and took it upon herself to personally select my tutors and confer with them over my curriculum. Under her guidance, I studied languages, becoming fluent in a full seven of them, and also mathematics, history, philosophy, the Classics and the writings of the early Church Fathers, architec-ture, and astronomy. Nor were the female accomplishments neglected; equal time was given to dancing, music, and sewing, both practical and ornamental, and also to outdoor pursuits such as riding, hunting, hawking, and archery. But even she brushed her skirts perilously close to Death when she dared argue with my father, contradicting him about religion. A careless hand dropped the warrant for her arrest in the corridor and I found it and brought it to her.

Careful observation had already taught me that my father would always distance himself from those he meant to condemn; he would not deign to face them lest their tears and pleas for mercy sway him. I urged her to go, to save herself before it was too late. I begged her to swallow her pride and throw herself at his feet – so great was my love for her that I implored her to grovel, though the very thought of it sickened me – to claim that she had only dared argue with him to profit from his superior knowledge, to learn from him, and also, as an added boon, to distract him from the pain of his sore leg.

Though I was but a child, she listened to me, and was saved, but I would never forget how close she came to danger, or the power of life and death my father had to wield over her as her sovereign lord, husband, and master. Or the shame that she, one of the torchbearers of enlightenment and reformation, must have felt to have to lower herself in such a manner and humbly declare womankind, whose champion she was, weak and inferior, and that God had created women to serve men, and no female should ever presume to contradict, question, or disobey her husband, father, brother, or indeed any male at all.

Already I knew the value of dissembling for self-preservation. Once my father had favoured women with sharp, clever minds and the gift of intelligent conversation, but after my mother he put docility and beauty first and foremost, so that his last wife, Catherine Parr, must need stifle her intellect and bridle her tongue and play perpetual pupil to my father’s teacher. I don’t know how she stood it, but it only matters that she survived it.

Six wives … four dead and two living. Their history clearly showed me that marriage is the road to doom and destruction for all womankind and affirmed my conviction that never would I walk it; I would go a virgin to my grave. But I also knew, and feared, that there would be times in the years to come when God would test me.

3

Mary

“The King is dead. Long live the King!” Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset, pronounced in a voice both loud and sombre. Even as Father’s minion, that heretical serpent Cranmer, leaned down to close Father’s eyes, all other eyes were turning towards the future – pale and weeping little Edward, aged only nine.

He sat there mute and quaking between my sister and me. And then he turned away from me and flung himself into Elizabeth’s arms, weeping more, I think, at the enormity of what lay ahead of him than for the loss of our father.