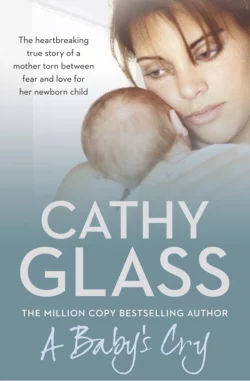

A Baby’s Cry

Cathy Glass

What could cause a mother to believe that giving away her newborn baby is her only option? Cathy Glass is about to find out. From author of Sunday Times and New York Times bestseller Damaged comes a harrowing and moving memoir about tiny Harrison, left in Cathy’s care, and the potentially fatal family secret of his beginnings.When Cathy is first asked to foster one-day old Harrison her only concern is if she will remember how to look after a baby. But upon collecting Harrison from the hospital, Cathy realises she has more to worry than she thought when she discovers that his background is shrouded in secrecy.She isn’t told why Harrison is in foster care and his social worker says only a few are aware of his very existence, and if his whereabouts became known his life, and that of his parents, could be in danger. Cathy tries to put her worries aside as she looks after Harrison, a beautiful baby, who is alert and engaging. Cathy and her children quickly bond with Harrison although they know that, inevitably, he will eventually be adopted.But when a woman Cathy doesn’t know starts appearing in the street outside her house acting suspiciously, Cathy fears for her own family’s safety and demands some answers from Harrison’s social worker. The social worker tells Cathy a little but what she says is very disturbing . How is this woman connected to Harrison and can she answer the questions that will affect Harrison’s whole life?

Copyright

HarperElement

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

and HarperElement are trademarks of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

First published by HarperElement 2012

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

A BABY’S CRY. © Cathy Glass 2012. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

ISBN: 9780007442638

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007445707

Version 2018-11-05

Dedication

To Dad with love

Contents

Title Page (#uc43d0c22-ec25-5e2e-ba2b-f84ceee359a4)

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Secretive

Chapter Two

Helping

Chapter Three

Alone in the World

Chapter Four

Bonding

Chapter Five

The Case

Chapter Six

The Mystery Deepens

Chapter Seven

Abandoned

Chapter Eight

Stranger at the Door

Chapter Nine

Section 20

Chapter Ten

Shut in a Cupboard

Chapter Eleven

Ellie

Chapter Twelve

A Demon Exorcized

Chapter Thirteen

Pure Evil

Chapter Fourteen

Shane

Chapter Fifteen

No Wiser

Chapter Sixteen

The Woman in the Street

Chapter Seventeen

Information Sharing

Chapter Eighteen

Staying Safe

Chapter Nineteen

A Right to Cry

Chapter Twenty

An Ideal World

Chapter Twenty-One

Honour

Chapter Twenty-Two

A Baby’s Cry

Chapter Twenty-Three

Late-Night Caller

Chapter Twenty-Four

Harrison

Chapter Twenty-Five

Best Christmas

Chapter Twenty-Six

Little Brother

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Contact

Chapter Twenty-Eight

The Decision

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Letting Go

Chapter Thirty

Upset

Chapter Thirty-One

Goodbye Harrison

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Exclusive sample chapter

Cathy Glass (#u465465ba-227a-5acc-aecf-7275b8c466f5)

About the Publisher (#u96f4bb98-26d7-543e-b1ae-af87c957d003)

Prologue

Children can come into foster care at any age and it is always sad, but most heartbreaking of all is when a newborn baby, sometimes only a few hours old, is taken from their mother and brought into care.

Certain details in this story, including names, places, and dates, have been changed to protect the family’s privacy.

Chapter One

Secretive

‘Could you look after a baby?’ Jill asked.

‘A baby!’ I said, astonished.

‘Yes, you know. You feed one end and change the other and they keep you up all night.’

‘Very funny, Jill,’ I said. Jill was my support social worker from Homefinders, the agency I fostered for. We enjoyed a good working relationship.

‘Actually, it’s not funny, Cathy,’ she said, her voice growing serious. ‘As we speak a baby is being born in the City Hospital. The social services have known for months that it would be coming into care but they haven’t anyone to look after it.’

‘But Jill,’ I exclaimed, ‘it’s years since I’ve looked after a baby, let alone a newborn. Not since Paula was a baby, and she’s five now. I think I might have my pram and cot in the loft but I haven’t any bottles, baby clothes or cot bedding.’

‘You could buy what you need and we’ll reimburse you. Cathy, I know you don’t normally look after babies – we save you for the more challenging children – and I wouldn’t have asked you, but all our baby carers are full. The social worker is desperate.’

I paused and thought. ‘How soon will the baby be leaving hospital?’ I asked, my heart aching at the thought of the mother and baby who were about to be separated.

‘Tomorrow.’

‘Tomorrow!’

‘Yes. Assuming it’s a normal birth, the social worker wants the baby collected as soon as the doctor has given it the OK.’

I paused and thought some more. I knew my children, Paula (five) and Adrian (nine), would love to foster a baby, but I felt a wave of panic. Babies are very tiny and fragile, and it seemed so long since I’d held a baby, let alone looked after one. Would I instinctively remember what to do: how to hold the baby, sterilize bottles, make up feeds, wind and bath it, etc.?

‘It’s not rocket science,’ Jill said, as though reading my thoughts. ‘Just read the label on the packet.’

‘Babies don’t come with labels, do they?’

Jill laughed. ‘No, I meant on the packet of formula.’

‘Why is the baby coming into care?’ I asked after a moment.

‘I don’t know. I’ll find out more from Cheryl, the social worker, when I call her back to say you can take the baby. Can I do that? Please, Cathy – pretty please if necessary.’

‘All right. But Jill, I’m going to need a lot of advice and …’

‘Thanks. Terrific. I’ll phone Cheryl now and then get back to you. Thanks, Cathy. Speak to you soon.’

And so I found myself standing in my sitting room with the phone in my hand expecting a baby in twenty-four hours.

Panic took hold. What should I do first? I had to go into the loft, find the cot and pram and whatever other baby equipment might be up there, and then make a list of what I needed to buy and go shopping. It was 10.30 a.m. Adrian and Paula were at school. There’s plenty of time to get organized and go shopping, I told myself, so calm down.

First, I went to the cupboard under the stairs and took out the pole to open the loft hatch; then I went upstairs and on to the landing. Extending the pole, I released the loft hatch and slowly lowered the loft ladders. I don’t like going into the loft because I hate spiders and I was sure the loft was a breeding ground for them. I gingerly climbed to the top of the ladders and then tentatively reached in and switched on the light. I scanned the loft for spiders before going in completely.

I spotted the cot and pram straightaway. They were both collapsed and covered with polythene sheeting to protect them from dust; I intended to sell them one day. I also spotted a bouncing cradle. All of these Adrian and Paula had used as babies. Carefully stepping around the other stored items in the loft and ducking to avoid the overhead beams, I kept a watchful eye out for any scurrying in the shadows and crossed to the baby equipment. Removing the polythene I saw they were in good condition and I carried them in their sections to the loft hatch opening and down the ladders; then I stacked them on the landing, to be assembled later. I returned up the ladders and switched off the loft light, and then closed the hatch and took the pole downstairs, where I returned it to the cupboard.

Perching on a breakfast stool in the kitchen I took a pen and paper and began making a list of the essential items I’d need to buy: cot mattress, cot and pram bedding, baby bath, changing mat, bottles and formula milk, first-size clothes, nappies, nappy wipes, baby bath cream, etc. As my list grew, so too did my anticipation and I began to feel a little surge of excitement at the thought of looking after a baby – although I was acutely aware that my gain would be another woman’s loss, as it meant that a mother would shortly be parted from her baby, which is always very very sad.

When the shopping list of baby equipment appeared to be complete and I couldn’t think of anything else, I tucked the list into my handbag, locked the back door and, slipping on my sandals, left the house to drive into town. It was a lovely summer’s day and as I drove my thoughts returned to the mother who was now in labour and whose baby I would shortly be looking after. I knew that taking her baby straight into care from hospital wasn’t a decision the social services would have taken lightly, as families are kept together wherever possible. The social services, therefore, must have had serious concerns for the baby’s safety. Possibly the mother had a history of abuse or neglect towards other children she’d had; maybe she was drink and or drug dependent; possibly she had mental health problems; or maybe she was a teenage mother who was unable to care for her infant. Whatever the reason, I hoped, as I always did with the children I fostered, that the mother would eventually recover and be able to look after her child, or if she was a teenage mother that the necessary support could be put in place to allow mother and child to be reunited.

When you think of the months of planning and the preparation that parents make when they find out they are expecting a baby, it was incredible that an hour after entering Mothercare I was pushing the trolley towards the checkout with all the essential items I would need, plus a few extras: I couldn’t resist the cuddly soft-toy elephant from the ‘baby’s first toys’ display, nor the bibs embroidered with Disney characters and the days of the week, nor the Froggy rattle set. I’d pay for these from my own money while the agency had said they would fund the essentials.

It was 1.15 as I paid at the till and then wheeled the trolley from the store and to the lift in the multistorey car park. I was expecting Jill to phone any time with more details and I had my mobile in my handbag with the volume on loud. Sure enough, as I closed the car boot and was about to get into the car my phone went off. Jill’s office number flashed up and when I answered she said, ‘It’s a boy. He’s called Harrison, and he’s healthy.’

‘Excellent,’ I said. ‘And his mother is well too?’

‘I believe so. Cheryl didn’t say much other than you should be ready to collect him tomorrow afternoon. She will telephone again tomorrow morning with the exact time to collect him.’

‘All right, Jill. I’ll be ready. I’ve just been shopping and I think I’ve got everything.’

‘Good. And Cathy, just to confirm the baby is healthy. There are no issues of him suffering withdrawal from drink or drugs. His mother is not an addict.’

‘Thank goodness,’ I said. ‘That’s a relief.’ For I was aware of the dreadful suffering endured by babies who are born addicted to their mother’s drugs. Once the umbilical cord is cut and the drug is no longer filtering into the baby’s blood they go ‘cold turkey’, just like adults withdrawing from a drug. Only it’s worse for babies because they don’t understand what’s happening to them. They scream in pain from agonizing cramps for hours and can’t be comforted by their carer. They shiver, shake, vomit and even fit, just as an adult addict does. It’s frightening and pitiful to watch, and it often takes many months before the baby is free from withdrawal. ‘Thank goodness,’ I said again.

‘And, Cathy,’ Jill said, her voice growing serious, ‘you need to prepare yourself for the possibility that you might meet Harrison’s mother at the hospital tomorrow. A nurse will be with you, but I thought I should warn you.’

‘Oh, yes, thank you. I hadn’t thought of that. That will be upsetting – poor woman. Do you know anything more about her?’

‘No. I asked Cheryl but she seemed a bit evasive. Secretive almost. I’ll be speaking to her again tomorrow to clarify arrangements for collecting the baby, so I hope I’ll find out more then.’

And that was the first indication of just how unusual this case would be. Jill was right when she said the social worker was being secretive, but it was not for any reason she or I could have possibly guessed.

Chapter Two

Helping

When I arrived home I unloaded all the bags of baby equipment from the boot of the car and then took them upstairs, where I stacked them in the spare bedroom. This was the bedroom I used for fostering and it was rarely empty, for there was always a child to be looked after. However, I’d already decided that baby Harrison wouldn’t be using this bedroom for the first few months but would be sleeping in the cot in my room, as Adrian and Paula had done when they were babies. This was a precautionary measure so that I could check on him and answer his cries immediately. And again my thoughts went sadly to Harrison’s mother, who wouldn’t have the opportunity to hear her baby cry at night or see him chuckle with delight during the day.

Having unloaded the car, I left all my purchases in their bags and wrappers in the bedroom and had just enough time for a cold drink before I had to leave to collect Adrian and Paula from school. They attended a local primary school about a five-minute drive away. They didn’t know yet that we were going to foster a baby and as I drove I pictured the looks on their faces when I told them. They would be so excited. Some of their friends had baby brothers and sisters and Paula, in particular, loved playing babies with her dolls: feeding them with a toy bottle, changing their nappies and sitting them on the potty. Sometimes Adrian joined in and more than once I’d been very moved by overhearing them tenderly nursing their ‘little darling’ and discussing their baby’s progress. Now we were going to do it for real, and I should make sure Adrian and Paula fully appreciated that a baby could not be treated as a toy and mustn’t be picked up unless I was in the room, which I’m sure they knew.

‘A baby!’ Paula squealed in delight as I met her in the playground and told her. ‘What, a real one?’

I smiled. ‘Yes, a real baby. I’m bringing him home from the hospital tomorrow.’

‘I can’t wait to tell my teacher!’ Paula exclaimed.

A minute later Adrian bounded over from his classroom exit, which was further along the building.

‘A baby!’ he exclaimed in surprise when I told him.

‘Yes, he was born today in the City Hospital,’ I said. ‘I’m going to collect him tomorrow afternoon.’

‘How was he born?’ Paula asked innocently as we began across the school playground.

‘Same as those rabbits you saw last year,’ Adrian said quickly, glancing over his shoulder to make sure his friends hadn’t heard Paula’s question.

‘Yuck!’ Paula said, screwing up her face. ‘That’s horrid.’

The previous summer we’d gone with friends to a working farm which had open days, and by chance in a fenced-off area of a barn we’d seen a rabbit giving birth. All the children watching had been enthralled and a little repulsed at this sight of nature in the raw, but as the man standing behind me had remarked: ‘At least we won’t have to explain the birds and bees to the kids now!’

‘What’s the baby’s name?’ Adrian now asked, changing the subject.

‘Harrison,’ I said.

‘Harrison,’ Paula repeated. ‘That’s a long name. I think I’ll call him Harry.’

‘Yes, that’s fine,’ I agreed. ‘Baby Harry sounds good.’ And I briefly wondered why his mother had chosen the name Harrison, which was an unusual name in England and more popular in America.

When we arrived home Adrian and Paula ran upstairs to the spare bedroom to see all the baby things I’d told them I’d bought. ‘It’s like Christmas!’ Paula called, for rarely were there so many store bags and packages in the house.

After dinner the children didn’t want to play in the garden, as they had been doing recently in the nice weather, but wanted to help me prepare Harrison’s bedroom. I thought it was a good idea for them to be involved, so that they wouldn’t feel excluded when Harrison arrived and I was having to devote a lot of my time to him.

The three of us went upstairs and I gave Paula the job of starting to unwind the polythene from the new cot mattress, while Adrian helped me carry the sections of the cot into my bedroom. He also helped me assemble it and once the frame was bolted into place he and Paula carried in the new mattress. I lowered in the mattress and then fetched the new bedding from the spare room. Taking the blankets and sheets out of their wrappers, we made up the cot. I felt a pang of nostalgia as I remembered first Adrian and then Paula sleeping in the cot as tiny babies.

‘It’s not very big,’ Adrian remarked. ‘Did I fit in there?’

‘Yes. You were a lot, lot smaller then,’ I said, smiling. Adrian was going to be tall like his father, who unfortunately no longer lived with us.

‘Can I climb in?’ Adrian said, making a move to lift a leg over the lowered side.

‘No, you’ll break it,’ I said. ‘And don’t be tempted to try and get in when I’m not here, will you?’

Adrian shook his head.

‘What about me?’ Paula asked. ‘I’m smaller than Adrian. Can I get in?’

‘No. You’re too heavy too. It’s only made for a baby’s weight. And just a reminder: you both know you mustn’t ever pick up Harrison when I’m not in the room?’ Both children nodded. ‘I want you to help me, but we have to do it together, OK?’

‘OK,’ Adrian said quickly, clearly feeling this was obvious, while Paula said: ‘Ellen in my class has a baby sister and her mother told her babies don’t bounce. That seems a silly thing to say because of course babies don’t bounce. They’re not balls.’

‘It’s a saying,’ I said. ‘To try and explain that babies are fragile and need to be treated very gently.’

‘I’ll tell Ellen,’ Paula said. ‘She didn’t understand either.’

‘Well, she’s daft,’ Adrian said, unable to resist a dig at his sister.

‘No she’s not,’ Paula retaliated. ‘She’s my friend. You’re daft.’ Whereupon Adrian stuck out his tongue at Paula.

‘Enough,’ I said. ‘Are you helping me or not?’ I’d found since Paula had started school that the gap between their ages seemed to have narrowed and sometimes Adrian delighted in winding up his sister – just as many siblings do.

‘Helping,’ they chorused.

‘Good.’

With the cot made up and in place a little way from my bed we returned to the spare bedroom, where I left Adrian and Paula, now friends again, to finish unpacking the bags and packages while I took the three-in-one pram downstairs, a section at a time. It was a pram, pushchair and car seat all in one. I set up the pram in the hall and another wave of nostalgia washed over me as I remembered how proud I’d felt pushing Adrian and Paula in the pram to the local shops and park. The pram base unclipped to allow the pushchair, which was also the car seat, to be fitted, and I guessed I’d be using the car seat first when I collected Harrison from the hospital. I returned upstairs, where Adrian and Paula had finished unpacking all the items.

‘Well done,’ I said. ‘That’s a big help.’

They watched as I stood the baby bath to one side – I’d take it into the bathroom when needed – and then I set the changing mat on the bed and arranged disposable nappies, lotions, creams and nappy bags on the bedside cabinet. Now I was organized I was starting to feel more confident that I would remember what to do. As Jill had said: you simply feed one end and change the other – repeatedly, as I remembered.

Once we’d finished unpacking, the children played outside while I cleared up the discarded packaging and then, downstairs, distributed it between the various recycling boxes and the dustbin. I hadn’t heard from Jill since her phone call earlier and I wasn’t really expecting to until the following day, when she’d said she’d phone once she’d spoken to Cheryl, the social worker, with the arrangements for collecting Harrison and I hoped some more background information. Apart from knowing Harrison’s first name, that I was to collect him tomorrow afternoon and that his mother wasn’t drink or drug dependent, I knew nothing at all about Harrison. Although it wasn’t unusual for there to be a lack of information if a foster child arrived as an emergency, this placement wasn’t an emergency. Jill had said that the social services had known about the mother for months, so I really couldn’t understand why arrangements had been left until the last minute and no information was available. Usually when a placement is planned (as this one should have been) before the child arrives I receive essential information on the child, which includes relevant medical and social history; the background to the case; and the child’s routine – although, as Harrison was a newborn baby it would be largely up to me to establish his routine. I assumed Jill would bring the necessary forms with her when she visited the following day.

That night Paula was very excited at the prospect of Harrison’s arrival, and after I’d read her a bedtime story she told me all the things she was going to do for him: help feed him; change and wind him; play with him; push the pram when we took him to the park to feed the ducks and so on. Clearly Harrison was going to be very well looked after and also very busy; I knew I would be busy too – especially with contact. When a young baby is brought into foster care there is usually a high level of contact initially, when the parents see their baby with a supervisor present, usually for a couple of hours each day, six or even seven days a week. This is to allow the parents to bond with their baby and vice versa, and also so that a parenting assessment can be completed as part of the legal process that will be running in the background. But a high level of contact has its down side, for if the court decides not to return the baby to live with its parents and instead places the child for adoption, then clearly the bond that has been created between the parents and the baby has to be (painfully) broken. However, the alternative – if there is no contact – is that a baby could be returned to parents without an attachment, which can have a huge negative impact on their future together and particularly for the child. I was, therefore, anticipating taking Harrison to and from supervised contact at the family centre every day.

So that when Jill phoned the following morning and said there wouldn’t be any contact at all I was shocked and confused.

Chapter Three

Alone in the World

‘What, none?’ I asked in amazement. ‘No contact at all?’

‘No,’ Jill confirmed, but she didn’t give a reason.

‘What about Harrison’s father? Grandparents? Aunts? Uncles? There must be someone who wants to see him, surely?’

‘Not as far as I know,’ Jill said; then, after a pause: ‘Look, Cathy, I’ve just spoken to Cheryl and she’s given me a little background information but it is highly confidential, and of a very delicate nature. I think it would be better if I saw you in person to tell you what I know.’

‘All right,’ I agreed reluctantly, for I was now intrigued and would have preferred to know straightaway.

‘But I’m afraid it won’t be today,’ Jill continued. ‘An emergency has arisen with a new carer – their child’s gone missing – and I need to talk to the police. Can I come tomorrow morning, say ten-thirty?’

‘Yes, I’ll be here.’

‘Good. Now to the arrangements for this afternoon. Cheryl has asked that you collect Harrison at one o’clock from the maternity ward at the City Hospital. The nurses will be expecting you, so go straight up to the ward. And don’t forget your ID; they’ll ask for it.’ Jill was referring to my fostering ID card, which carers are expected to carry with them when on fostering business.

‘I’ll remember,’ I confirmed.

‘If you need me, phone my mobile – I’ll leave it on silent – but I’m not expecting a problem.’

‘Will I be meeting Harrison’s mother at the hospital?’ I asked. This was now starting to worry me.

‘I think you might,’ Jill said. ‘She will be discharged at the same time as her baby. But Cheryl has assured me that Harrison’s mother is very pleasant and won’t give you any trouble. And it will be reassuring for her to meet you – to see who is looking after Harrison.’

‘Yes, I can see that,’ I said, confused, for this didn’t sound like an abusive or negligent mother. ‘And Harrison’s mother doesn’t want any contact with her baby after today?’ I queried again.

‘No. I’ll explain tomorrow. Oh, yes, and Cathy, Harrison has dual heritage. Mum is British Asian, I’m not sure about Dad, but there are no cultural or religious needs, so just look after Harrison as you would any baby.’

‘Yes, Jill. All right.’

It was now 10.30 a.m. and my nervous anticipation was starting to build. I would leave the house in two hours – at 12.30 p.m. – to arrive at the hospital for 1.00. I went upstairs to the spare bedroom and double-checked I had everything I needed. I decided to make up a bag of essential items to take with me to the hospital. Although the hospital was only a twenty-minute drive away I wouldn’t know when Harrison had last been fed or changed, so it made sense to be prepared. Taking a couple of nappies, nappy bags and a packet of baby wipes I went downstairs and found a small holdall in the cupboard under the stairs. Tucking these items into the holdall I went through to the kitchen and took a carton of ready-made formula from the cupboard – I’d bought a few cartons for emergency use, as they could be used at room temperature anywhere. The powder formula was in the cupboard and the bottles I’d sterilized that morning were in the sterilizing unit, ready. I remembered I’d fed Adrian and Paula more or less ‘on demand’ rather than following a strict feeding routine, and I anticipated doing the same with Harry, although of course it would be formula not breast milk.

I placed the carton of milk and a sterilized bottle into a clean plastic bag and put them in the holdall. I then went into the hall and placed the holdall on top of the carry car seat, which I’d previously detached from the pram. I’d no idea what Harry had in the way of clothes; I assumed not much. Children coming into care usually come from impoverished backgrounds, so when I’d been shopping the day before I’d bought some first-size sleepsuits and also a pram blanket. Although it was summer and Harry would be nestled in the ‘cosy’ in the car seat, he would be leaving a very warm hospital ward, so I put the blanket in the holdall.

Having checked that I had everything I needed for Harry’s journey home, I busied myself with housework, while keeping a watchful eye on the time. My thoughts repeatedly flashed to Harrison and his mother, and I wondered what she was doing now. Feeding or changing Harrison? Sitting by his crib gazing at her baby as he slept, as I had done with Adrian and Paula? Or perhaps she was holding Harrison and making the most of their time together before she had to say goodbye? What she could be thinking as she prepared to part from her baby I couldn’t begin to imagine.

Shortly after twelve noon I brought in the washing from the line, put out our cat, Toscha, for a run and locked the back door. With my pulse quickening from anticipation and anxiety I went down the hall, picked up my handbag, the holdall and the baby seat, and went out the front door. Having placed the bags and car seat in the rear of the car, I climbed into the car and started the engine. I pulled off the drive, steeling myself for what I was about to do.

In the ten years I’d been fostering I’d met many parents of children in care but never a mother whose baby I was about to take away. Usually an optimist and able to find something positive in any situation I was now struggling as I visualized going on to the hospital ward. What was I going to say to the mother, whose name I didn’t even know? The congratulations we normally give to new parents – What a beautiful baby, you must be very proud – certainly wouldn’t be appropriate. Nor could I rely on the reassurance I usually offer the distraught parents of children who’ve just been taken into care – that they will see their children again soon at contact – for there was no contact and Harrison’s mother wouldn’t be seeing her son again soon. And supposing Harrison’s father was there? Jill hadn’t mentioned that possibility and I hadn’t thought to ask her. Supposing Harrison’s father was there and was upset and angry? I hoped there wouldn’t be an ugly scene. There were so many unknowns in this case it was very worrying, and without doubt taking baby Harrison from his parents was the most upsetting thing I’d ever been asked to do.

It was 12.50 as I parked in the hospital car park, and then fed the meter. I placed the ticket on my dashboard and leaving the holdall on the back seat I took out my handbag and the carry car seat and crossed the car park. It was a lovely summer’s day in early July, a day that would normally lighten my spirits whatever mood I was in, but not now. As I entered the main doors of the hospital I felt my stomach churn. I just wanted to get this awful deed over and done with and go home and look after Harrison.

Inside the hospital I followed the signs to the maternity ward – up a flight of stairs and along a corridor, where I turned right. I now stood outside the security-locked doors to the ward. Taking a deep breath to steady my nerves I delved in my handbag for my ID card and then pressed the security buzzer. My heart was beating fast and I felt hot as my fingers clenched around the handle of the baby seat I was carrying.

Presently a voice came through the intercom grid: ‘Maternity.’

‘Hello,’ I said, speaking into the grid. ‘It’s Cathy Glass. I’m a foster carer. I’ve come to collect Harrison.’

It went quiet for a moment and I thought she’d gone away. Then as I was about to press the button again her voice said: ‘Come through,’ and the door clicked open.

I went in and then down a short corridor, which opened on to the ward. It was a long traditional-style ward with a row of beds either side, each one separated by a curtain and bedside cabinet. Beside each bed was a hospital crib with a baby. I glanced anxiously around and then a nurse came over.

‘Mrs Glass?’

‘Yes.’ I showed her my ID card.

She nodded. ‘You’ve come for Harrison.’

‘Yes.’

‘This way.’

My mouth went dry as I followed the nurse down the centre of the ward. Other mothers were resting on their beds or standing by the cribs tending to their babies; some glanced up as we passed. The ward was very warm and surprisingly quiet, with only one baby crying. There was a joyous atmosphere, with baby congratulation cards strung over bed heads, although I imagined this was in contrast to how Harrison’s mother must be feeling.

‘He’s over here, so we can keep an eye on him,’ the nurse said, leading me to the last bed on the right, which was closest to the nurses’ station.

The curtain was pulled back and my eyes went first to the crib containing Harrison and then to the empty bed beside it. ‘Is Harrison’s mother here?’ I asked.

‘No. She left half an hour ago, as soon as she was discharged.’

A mixture of relief and disappointment flooded through me. Relief that what could have been a very awkward and upsetting meeting had been avoided, but disappointment that I hadn’t had the opportunity to reassure her I would take good care of her baby. And I guess I’d been curious too, for I knew so little about Harrison’s mother or background.

‘He’s a lovely little chap,’ the nurse said, standing by the crib and gazing down at him. ‘Feeding and sleeping just as a baby should.’

My heart melted as I joined the nurse beside the crib and looked down at Harrison. He was swaddled in a white blanket with just his little face visible from beneath a small white hat. His tiny features were perfect and his light brown skin was flawless. His eyes were closed but one little fist was pressed to his chin as though he was deep in thought.

‘He’s a beautiful baby,’ I said. ‘Absolutely beautiful. He looks very healthy. How much does he weigh?’

‘He was seven pounds two ounces at birth,’ the nurse said. ‘That’s three thousand two hundred and thirty-one grams. The social worker phoned and said to tell you she will bring the paperwork when she visits you later in the week.’ I nodded and gazed down again at Harrison as the nurse continued: ‘And the health visitor will see you in the next few days and bring Harrison’s red book.’ (The red book is a record of the baby’s health and development and is known as the red book simply because the book is bound in red.)

‘Thank you,’ I said.

‘Oh yes, and Mum has left some things for Harrison,’ the nurse said, pointing to a grey trolley case standing on the floor by the bed. ‘Rihanna wasn’t sure what you would need.’

‘Rihanna is Harrison’s mother’s name?’ I asked.

‘Yes, she’s a lovely lady. Why isn’t she keeping her baby?’ The nurse looked at me as though she thought I would know, while I was surprised she didn’t know.

‘I’ve no idea,’ I said. ‘I haven’t any details. I don’t even know Harrison’s surname.’

‘It’s Smith,’ the nurse said. ‘Which I understand is his father’s surname.’

‘Was the father here?’

‘Oh no,’ the nurse said, again surprised I didn’t know. ‘Rihanna wouldn’t allow any visitors.’

I looked at her, even more puzzled and intrigued, as a woman in a bed behind us called ‘Nurse!’ The nurse turned and said, ‘I’ll be with you in a minute, Mrs Wilson.’ Then to me: ‘Well, good luck. Do you need any help getting to the car?’

‘No. I’ll be fine.’

The nurse watched me as I set the carry car seat and my handbag on the floor and turned to the crib. ‘When was he last fed?’ I asked as I leant forward, ready to pick up Harrison.

‘Rihanna fed and changed him before she left, so he’ll be fine for a couple of hours.’

‘Thanks,’ I said. I gently tucked my hands under Harrison’s tiny form and picked him up. ‘Is this blanket his?’ I asked, for it was similar to those the other babies had on their cots.

‘Yes. Mum brought it in, and the clothes he’s wearing.’ I saw Harrison was dressed in a light blue sleepsuit similar to the ones I’d bought from Mothercare.

I lowered Harrison carefully into the carry car seat as the nurse left to attend to the other mother. His little face puckered at being moved but he didn’t wake or cry. He was so cute, my heart melted. I gently fastened the safety harness and then tucked the blanket loosely over him. His little fist came up to his chin but he obligingly stayed asleep.

Straightening, I looped my handbag over my shoulder, took the handle of the trolley case in one hand and the carry car seat in the other, and began slowly down the ward towards the exit. A few mothers looked up as I passed; it must have seemed strange for them to see me arrive alone and then leave with a baby. I wondered if Rihanna had spoken to any of the other mothers on the ward; I’d made lasting friendships when I’d been in hospital having Adrian and Paula, but somehow I didn’t think that would be so for Rihanna. The nurse had said Rihanna had refused to allow visitors, and the secrecy surrounding her and Harrison led me to believe that for whatever reason Rihanna was very alone in the world, as indeed was her son.

I left the building and carefully made my way across the hospital car park, all the while glancing at Harrison, whose little eyes were screwed shut against the light.

‘We’ll be home soon,’ I whispered as we arrived at the car.

I unlocked the car, and then leaning into the back carefully placed the carry car seat into position. I strapped it securely into place with the seatbelt. Harrison’s bottom lip gave a little sucking motion as babies often do but he stayed asleep. I checked that all the straps were secure and then stood for a moment looking at Harrison, completely overawed. The responsibility hit me. Here I was solely in charge of this tiny newborn baby, who would be relying on me – a stranger – for everything he needed: for life itself. The responsibility of any parent is enormous but as a foster carer it seemed even greater – being responsible for someone else’s child – and I hoped I was capable of the task.

Quietly closing the car door so I wouldn’t wake him, I stowed the trolley case and my handbag in the boot, then went round and climbed into the driver’s seat. That was the worst part over with, I told myself, the bit I’d been dreading. I was pleased I’d collected Harrison and there’d been no upsetting scene; and shortly I would be home and looking after him. What I didn’t know then was that in collecting Harrison I had begun a very upsetting and traumatic journey that would often reduce me to tears. For now I was simply one very proud foster mother of a darling little baby boy.

Chapter Four

Bonding

Harrison slept peacefully during the car ride home and didn’t wake until I pulled on to the drive and cut the engine. When the soporific motion of the car stopped he gave one little whimper and then his brow furrowed as though he was trying to make sense of what was going on around him.

‘It’s OK, love,’ I soothed gently, as I got out and then opened the rear door. ‘We’re home now.’

Releasing the belt that held his car seat in place I carefully lifted out the seat and closed the door. I held the handle of the seat with one hand while I opened the boot with the other. I took out the bags and trolley case and then pressed the fob to lock the car. In the porch I stood the trolley case to one side while I opened the front door, now remembering that two hands are not enough when you have a baby. Harrison gave another little cry, louder this time, so I guessed he was starting to feel hungry. Leaving the bags in the hall I carried him in the seat through to the kitchen and stood it safely on the floor to one side. I knew it wasn’t recommended to leave a baby asleep for long periods in one of these seats – they’re bad for the baby’s spine, as they are curled slightly forward and not flat – so once I’d fed Harrison I would tuck him into his pram, where he could lie flat.

I took one of the sterilized bottles from the sterilizing unit and, using water I’d previously boiled and following the instructions on the packet of formula (which I’d also read earlier), I carefully made up the milk. Although I’d breastfed both my children I’d also used formula milk for Adrian, as he’d been a big baby who’d been constantly hungry. It occurred to me how different this homecoming was from when I’d arrived home with Adrian and Paula: John, my husband, had collected me from hospital and my parents had been waiting at home to welcome me and help with their new grandchild. Now there was just Harrison and me, and that seemed to highlight how alone Harrison was in the world.

Feeling rather clever that I’d made up the bottle of formula without any mishaps I carefully lifted Harrison from the car seat and carried him through to the sitting room to feed him. I sat on the sofa and gently laid him in the crook of my left arm and then put the teat of the bottle to his lips. Obligingly, he immediately opened his mouth, latched on to the teat and began sucking hungrily. I relaxed back a little on the sofa and looked at him in my arms as he fed. I’d forgotten how all-consuming feeding is for a newborn baby – it occupies and takes over their whole body. Harrison’s eyes were closed in concentration, and as he gulped down the warm milk little muscles in his face twitched with delight, while his fists and feet flexed open and closed in contentment. For a baby feeding is what matters most in the whole wide world and their life revolves around it.

As Harrison fed I could feel the warmth of his little body pressed against mine; likewise he would be able to feel the comfort of my body. The close bodily contact between a mother and baby, especially during feeding, is vital to the bonding process. I wondered how Harrison’s mother had felt when she’d fed Harrison for the last time before she’d left the hospital; when she’d gazed down at her son knowing that once she’d fed and changed him and returned him to the crib she would never touch or feel him again. It was so very, very sad and I found it impossible to imagine.

Harrison gulped down half the milk in the bottle and then suddenly stopped, pulled a face and spat out the teat. I wondered if he might need winding before he took the rest of the bottle, so I gently raised him into a sitting position and, supporting his chin with my right hand, I began gently rubbing his back with the palm of my left hand. His little white hat had slipped to one side and I took it off; it was warm in the house. Harrison had beautiful hair – a fine dark down covered most of his head, which made him look older than a newborn. After a moment of being winded he burped and a small rivulet of milk trickled from the corner of his mouth and on to his sleepsuit. I now realized I’d forgotten to bring in a bib with me. I carefully stood and carried Harrison into the kitchen, where I took one of the bibs I’d bought from the drawer, and then tore off a strip of kitchen towel and wiped the milk from his mouth and the sleepsuit. Returning to the sofa I lay Harrison in my left arm again and, tucking the bib under his chin, gave him the rest of the bottle.

Toscha, our cat, sauntered in, clearly curious, having let herself in through the cat flap. She miaowed, as she always did when she first saw either the children or me, and then rubbed herself around my legs. ‘Good girl,’ I said. ‘This is Harrison.’ But I would make sure Toscha was kept well away from Harrison, for much as we loved her I knew it was dangerous and unhygienic to allow animals near young babies. Toscha gave another little miaow and wandered off, her curiosity satisfied.

Now the bottle of milk was finished I wondered if Harrison might need a change of nappy, so I stood to go upstairs, where the changing mat, nappies and creams were – in the spare bedroom. But before I got to the sitting-room door the phone rang. I returned to the sofa and picked up the handset from the corner unit.

‘Hello?’

‘How’s the little man doing?’ Jill asked. She was phoning from her mobile; I could hear traffic in the background.

‘Great,’ I said. ‘He’s in my arms now. I’ve fed him; he’s taken all the bottle, and now I’m going to change him.’

‘There! I told you you’d remember what do to,’ she said. ‘It’s like riding a bicycle: you don’t forget once you’ve done it. Have you got everything you need?’

‘Yes, I think so. The hospital said the health visitor would visit in the next few days, so I’ll be able to ask her, if there’s anything I don’t know.’

‘Good. I’ll see you tomorrow then at ten-thirty and Cheryl would like to visit you and Harrison on Friday morning. She said it would be between eleven and twelve o’clock. Is that OK with you?’

‘Yes. Fine.’

‘She’ll bring the paperwork. Do you want me to come then as well?’

‘Not unless you want to. I know what to do.’

‘Great. See you both tomorrow.’

As I put the phone down Harrison went very still and frowned. A smell rose from his nappy.

‘I think it’s time for a nappy change, little fellow,’ I said, kissing the tip of his nose. He looked into my eyes and seemed to smile at me. I felt an overwhelming surge of love and protectiveness towards him, just as any mother would.

Upstairs, I went into the spare bedroom, which contained all the baby equipment apart from the cot, which was in my bedroom. I lay Harrison on the changing mat on the bed and began unbuttoning his sleepsuit. He watched me as I worked and then he waved his little fists in the air. I took off the nappy, cleaned him with the baby wipes, and then put him in a clean nappy. He was so good throughout the whole process, as if he sensed I was new to this and was helping me. I placed the soiled nappy and wipes in a nappy bag, which I knotted, ready to throw in the bin. It was only then I remembered that as a foster carer I was supposed to use disposable gloves when changing a baby’s nappy, just as I was supposed to use them when clearing up bodily fluids from any foster child. This was part of our ‘safer caring policy’, designed to keep the whole family safe from the transmission of infectious diseases. HIV, Hepatitis B and C (for example) can be spread through bodily fluids – blood, saliva, faeces, etc. – and whereas a birth mother usually knows she hasn’t any of these diseases and therefore hasn’t transmitted them to her baby through the umbilical cord, I as the foster carer usually did not know (unless I was told), so we practised safer caring. And while Jill had said Harrison’s mother wasn’t a drug addict – so the chances of Harrison carrying a virus were slim – I obviously couldn’t be certain. Having placed Harrison safely in the bouncing cradle, I went through to the bathroom and thoroughly washed my hands in hot soapy water. I then returned to the bedroom and took the packet of disposable gloves I’d bought the day before from the drawer and placed them beside the changing mat so that I would remember to use a pair next time.

It was now 2.30 and at three o’clock I would need to leave the house to collect Adrian and Paula from school. I carried Harrison and the bouncing cradle downstairs and sat him in the cradle in the sitting room while I went into the kitchen and poured myself a glass of water. I hadn’t had time for lunch; I’d make up for it at dinner, but I was thirsty. I drank the water and then returned to the sitting room. I wanted to quickly telephone my parents. I hadn’t told them Harrison was coming; it had all happened so quickly, and also I’d wanted to save them from worrying. Harrison, now fed and changed, was clearly feeling very comfortable and starting to doze so, perching on the sofa, I quietly picked up the phone and dialled my parents’ number. Mum’s voice answered with their number.

‘Hi, Mum, it’s Cathy,’ I whispered so that I didn’t disturb Harrison. ‘I have a baby boy.’

‘Pardon?’ she said. ‘I can’t hear you properly. It’s a bad line. I thought you said you’d had a baby?’

‘I have,’ I said slightly louder, smiling to myself. ‘We’re fostering a baby. He’s only two days old.’

‘A baby. Two days old!’ Mum repeated, surprised, and confirming she’d heard right.

‘Yes. I collected him from the hospital a couple of hours ago. He’s called Harrison and he’s lovely.’

‘Good gracious me!’ Mum exclaimed. ‘How are you managing with a baby?’

‘All right so far. I’ve fed and changed him and he didn’t complain. Soon I’ll take him in the car to meet Adrian and Paula from school. Come and visit as soon as you like.’

‘We will,’ Mum said excitedly. ‘I’ll speak to your father as soon as he arrives home from work and we’ll arrange to come over. How long do you think you’ll have him for?’

‘I don’t know yet. I’m seeing Jill tomorrow, so I should know more then.’

‘You’ll get very attached to him,’ Mum warned. ‘I know you do with all the children you look after, but a baby … Well, how will you ever be able to give him up?’

‘I’ll worry about that when the time comes,’ I said, lightly dismissive. ‘He’s only just arrived.’ Yet as I finished talking to Mum and we said goodbye I knew she was right. It was going to be heartbreaking when we eventually had to say goodbye to Harrison, and not only for Adrian, Paula and me but also for Harrison.

At 2.50, allowing plenty of time to collect Adrian and Paula from school, I carefully lifted Harrison, still asleep, from the bouncing cradle and tucked him into the carry car seat. The trolley bag from Harrison’s mother was still in the hall and I now took it upstairs and put it in Harrison’s room, where it would be out of the way. I’d unpack it later when I had the time. Downstairs again, I picked up the pram chassis (which the baby seat fitted into) and, opening the front door, took it out to the car, where I stowed it in the boot. I returned to the hall and carried Harrison in the seat to the car and strapped him under the rear belt, carefully checking all the straps. While all this took time and conscious thought I knew that very soon it would become an easy routine which I would follow automatically on leaving the house, just as I had with Adrian and Paula.

I felt self-conscious and also excited as I entered the playground pushing the pram that afternoon. Although Adrian and Paula knew I would be collecting Harrison from the hospital, it had all happened so quickly that none of my friends and mothers to whom I chatted in the playground knew I would be arriving with a baby. I was right in thinking it would cause some interest and comments, for within a minute of entering the playground Harrison was the centre of attention. ‘Oh, what a darling baby!’ … ‘Isn’t he cute!’ … ‘That was quick work, Cathy!’ … ‘He’s not very old’ … ‘You’re a sly one – who’s the lucky guy?’ … ‘I’m broody’ … and so on.

When the bell rang, signalling the end of school, I pushed the pram towards the door Paula would come out of. Those mothers with children in the same class came with me, still chatting and asking questions about Harrison, while others went off to collect children from different exits. While I was able to answer questions about Harrison’s name, weight and when he was born, to most of the other questions I replied a polite ‘Sorry I don’t know.’ And even if I had known details of Harrison’s background, confidentiality forbade me from sharing these with anyone apart from the other professionals involved in his case.

As soon as Paula came out she grinned and rushed over. ‘Can I see him?’ she said, edging her way in between two mothers who were still leaning over the pram.

‘Hi, Harry,’ Paula said, and gave a little wave.

Harry replied by opening his mouth wide and giving a big yawn.

An affectionate chorus of ‘Aaahhh’ went up from the two mothers before they went off to collect their own children.

‘Can I push the pram?’ Paula asked, passing me her reading folder to carry and taking hold of the handlebar.

Adrian appeared with Josh, a boy from his class. ‘That’s him,’ Adrian said to Josh, pointing at the pram.

‘I’ve got one at home,’ Josh said, pulling a face. ‘They’re very smelly. Poo!’ he said, holding his nose for emphasis. Both boys dissolved into laughter.

‘Sshh, you’ll wake him,’ Paula cautioned, assuming a maternal role.

‘Mine cries and poos all day and night,’ Josh said happily, pulling another face, before running over to his mother, who was also pushing a pram.

‘Have you had a good day at school?’ I finally got to ask.

‘Yes. I got ten out of ten in the spelling test,’ Adrian said. ‘And Andrew’s asked me to his football party. Can I go?’

‘I’m sure you can. When is it?’

‘He’s giving out the invitations tomorrow. An ex-Liverpool player’s going to coach us.’

‘Sounds good,’ I said.

We began across the playground, with Adrian still chatting excitedly about the forthcoming football party, and Paula proudly pushing the pram and shushing Adrian not to disturb Harrison, while Harrison was trying to open his eyes and see what all the fuss was about. I wondered if Harrison’s mother had fully appreciated the joy of being with children when she’d made the decision not to see her son; or perhaps she had and, unable to keep Harrison, had decided that no contact would be less painful than seeing him and having to say goodbye.

I was nearer the truth than I realized.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/cathy-glass/a-baby-s-cry/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Cathy Glass

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1227.49 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: What could cause a mother to believe that giving away her newborn baby is her only option? Cathy Glass is about to find out. From author of Sunday Times and New York Times bestseller Damaged comes a harrowing and moving memoir about tiny Harrison, left in Cathy’s care, and the potentially fatal family secret of his beginnings.When Cathy is first asked to foster one-day old Harrison her only concern is if she will remember how to look after a baby. But upon collecting Harrison from the hospital, Cathy realises she has more to worry than she thought when she discovers that his background is shrouded in secrecy.She isn’t told why Harrison is in foster care and his social worker says only a few are aware of his very existence, and if his whereabouts became known his life, and that of his parents, could be in danger. Cathy tries to put her worries aside as she looks after Harrison, a beautiful baby, who is alert and engaging. Cathy and her children quickly bond with Harrison although they know that, inevitably, he will eventually be adopted.But when a woman Cathy doesn’t know starts appearing in the street outside her house acting suspiciously, Cathy fears for her own family’s safety and demands some answers from Harrison’s social worker. The social worker tells Cathy a little but what she says is very disturbing . How is this woman connected to Harrison and can she answer the questions that will affect Harrison’s whole life?