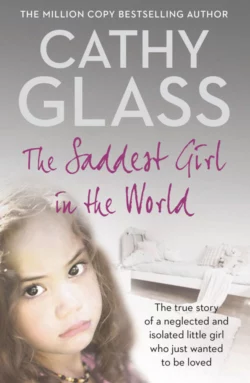

The Saddest Girl in the World

Cathy Glass

The Sunday Times and New York Times bestselling author of Damaged tells the true story of Donna, who came into foster care aged ten, having been abused, victimised and rejected by her family.Donna had been in foster care with her two young brothers for three weeks when she is abruptly moved to Cathy’s. When Donna arrives she is silent, withdrawn and walks with her shoulders hunched forward and her head down. Donna is clearly a very haunted child and refuses to interact with Cathy’s children Adrian and Paula.After patience and encouragement from Cathy, Donna slowly starts to talk and tells Cathy that she blames herself for her and her brothers being placed in care. The social services were aware that Donna and her brothers had been neglected by their alcoholic mother, but no one realised the extent of the abuse they were forced to suffer. The truth of the physical torment she was put through slowly emerges, and as Donna grows to trust Cathy she tells her how her mother used to make her wash herself with wire wool so that she could get rid of her skin colour as her mother was so ashamed that Donna was mixed race.The psychological wounds caused by the bullying she received also start to resurface when Donna starts reenacting the ways she was treated at home by hitting and bullying Paula, so much so that Cathy can’t let Donna out of her sight.As the pressure begins to mount on Cathy to help this child, things start to get worse and Donna begins behaving in erratic ways, trashing her bedroom and being regularly abusive towards Cathy’s children. Cathy begins to wonder if she can find a way to help this child or if Donna’s scars run too deep.

Copyright (#ulink_b7137342-fb95-5676-8e43-ffa1597b0cca)

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the recollections of Cathy Glass. The names of people, places, dates and details of events have been changed to protect the privacy of others.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2009

Copyright © Cathy Glass 2007

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007281039

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2009 ISBN: 9780007321575

Version: 2016–08–19

Contents

Cover (#ub641dd09-3e1e-5466-998a-4dcd3e8b2cdc)

Title Page (#u257466ee-f28d-5d82-bd8f-ca688a3463e9)

Copyright (#ulink_2368aaa1-75f7-531d-af91-210114f9078d)

Prologue (#u5ae2c722-3889-5c5c-8e1f-666963281a34)

Chapter One - Sibling Rivalry (#u0efb0b46-0c07-5151-b4ab-5d521c0608e6)

Chapter Two - So Dreadfully Sad (#u24f75101-a7ea-5d54-8064-6b37b47e8b43)

Chapter Three - Donna (#ue4719bb1-a64a-5ea9-8bc5-4a18b620947f)

Chapter Four - Silence (#udce768ef-bb05-52ec-bc69-16265ba9d38e)

Chapter Five - Cath—ie (#ue204a923-4650-5080-b527-dbf092333876)

Chapter Six - Amateur Psychology (#ufabefa8a-0422-566a-9f7d-4a892bddbe03)

Chapter Seven - Runt of the Litter (#uad9a9fc9-e68b-530b-a055-f77f3de4958b)

Chapter Eight - Dirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine - Outcast (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten - Tablets (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven - A Small Achievement (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve - Working as a Family (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen - The Birthday Party (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen - No Dirty Washing (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen - Mummy Christmas (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen - Winter Break (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen - Final Rejection (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen - Don't Stop Loving Me (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen - Paula's Present (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty - The Question (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-one - A Kind Person (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-two - Marlene (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-three - Lilac (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-four - Introductions (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-five - Moving On (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Exclusive sample chapter (#litres_trial_promo)

Cathy Glass (#litres_trial_promo)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Cathy Glass (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_87efa8b3-3c5e-5aed-9e71-aa4859bb1ec3)

This is the story of Donna, who came to live with me when she was ten. At the time I had been fostering for eleven years, and it is set before I had fostered Lucy, whom I went on to adopt. When Donna arrived, my son Adrian was ten and my daughter Paula was six; the impact Donna had on our lives was enormous, and what she achieved has stayed with us.

Chapter One Sibling Rivalry (#ulink_d6d1190d-099e-5a92-bd71-5dc768e9c806)

It was the third week in August, and Adrian, Paula and I were enjoying the long summer holidays, when the routine of school was as far behind us as it was in front. The weather was excellent and we were making the most of the long warm days, clear blue skies and the chance to spend some time together. Our previous foster child, Tina, had returned to live with her mother the week before and, although we had been sorry to see her go at the end of her six-month stay with us, we were happy for her. Her mother had sorted out her life and removed herself from a highly abusive partner. Although they would still be monitored by the social services, their future looked very positive. Tina's mother wanted to do what was best for her daughter and appeared to have just lost her way for a while — mother and daughter clearly loved each other.

I wasn't expecting to have another foster child placed with me until the start of the new school term in September. August is considered a ‘quiet time’ for the Looked After Children's teams at the social services, not because children aren't being abused or families aren't in crises, but simply because no one knows about them. It is a sad fact that once children return to school in September teachers start to see bruises on children, hear them talk of being left home alone or not being fed, or note that a child appears withdrawn, upset and uncared for, and then they raise their concerns. One of the busiest times for the Looked After Children's team and foster carers is late September and October, and also sadly after Christmas, when the strain on a dysfunctional family of being thrust together for a whole week finally takes its toll.

It was with some surprise, therefore, that having come in from the garden, where I had been hanging out the washing, to answer the phone, I heard Jill's voice. Jill was my support social worker from Homefinders Fostering Agency, the agency for whom I fostered.

‘Hi, Cathy,’ Jill said in her usual bright tone. ‘Enjoying the sun?’

‘Absolutely. Did you have a good holiday?’

‘Yes, thanks. Crete was lovely, although two days back and I'm ready for another holiday.’

‘Is the agency busy, then?’ I asked, surprised.

‘No, but I'm in the office alone this week. Rose and Mike are both away.’ Jill paused, and I waited, for I doubted she had phoned simply to ask if I was enjoying the sun or lament the passing of her holiday. I was right. ‘Cathy, I've just had a phone call from a social worker, Edna Smith. She's lovely, a real treasure, and she is looking to move a child — Donna, who was brought into care at the end of July. I immediately thought of you.’

I gave a small laugh of acknowledgement, for without doubt this prefaced trouble. A child who had to be moved from her carer after three weeks suggested the child had been acting out and playing up big time, to the point where the carer could no longer cope.

‘What has she done?’ I asked.

It was Jill's turn to give a small laugh. ‘I'm not really sure, and neither is Edna. All the carers are saying is that Donna doesn't get along with her two younger brothers. The three of them were placed together.’

‘That doesn't sound like much of a reason for moving her,’ I said. Children are only moved from a foster home when it is absolutely essential and the placement has irretrievably broken down, for clearly it is very unsettling for a child to move home.

‘No, that's what I said, and Edna feels the same. Edna is on her way to visit the carers now and see what's going on. Hopefully she'll be able to smooth things over, but is it OK if I give her your number so that she can call you direct if she needs to?’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said. ‘I'll be in until lunchtime, and then I thought I would take Adrian and Paula to the park. I'll have my mobile with me, so give Edna both numbers. I assume that even if Donna has to be moved there won't be a rush?’

‘No, I shouldn't think so. And you're happy to take her, if necessary?’

‘Yes. How old is she?’

‘Ten, but I understand she is quite a big girl and looks and acts older than her years.’

‘OK, no problem. Hopefully Edna can sort it out if it's only sibling rivalry, and Donna won't have to move.’

‘Yes,’ Jill agreed. ‘Thanks. Enjoy the rest of your day.’

‘And you.’

She sighed. ‘At work?’

I returned to the garden to finish hanging out the washing. Adrian and Paula were in the garden, playing in the toy sandpit. While Paula was happy to sit at the edge of the sandpit and make little animal sand shapes with the plastic moulds, Adrian was busy transporting the sand with aid of a large plastic digger to various places on the lawn. There were now quite sizeable hills of sand dotted on the grass, as if some mischievous mole had been busy underground. I knew that the sand, now mixed with grass, would not be welcomed back into the sandpit by Paula, who liked the sand, as she did most things, clean.

‘Try to keep the sand in the sandpit. Good boy,’ I said to Adrian as I passed.

‘I'm building a motorway,’ he said. ‘I'm going to need cement and water to mix with the sand, and then it will set hard into concrete.’

‘Oh yes?’ I asked doubtfully.

‘It's to make the pillars that hold up the bridges on the motorway. Then I'm going to bury dead bodies in the cement in the pillar.’

‘What?’ I said. Paula looked up.

‘They hide dead bodies in the cement,’ Adrian confirmed.

‘Whoever told you that?’

‘Brad at school. He said the Mafia murder people who owe them money, and then put the dead bodies in the pillars on the motorway bridges. No one ever finds them.’

‘Charming,’ I said. ‘Perhaps you could build a more traditional bridge without bodies. And preferably keeping the sand in the sandpit.’

‘Look!’ he continued, unperturbed. ‘I've already buried one body.’

I paused from hanging up the washing as Adrian quickly demolished one of the molehills of sand with the digger to reveal a small doll caked in sand.

‘That's mine!’ Paula squealed. ‘It's Topsy! You've taken her from my doll's house!’ Her eyes immediately misted.

‘Adrian,’ I said, ‘did you ask Paula if you could borrow Topsy and bury her in sand?’

‘She's not hurt,’ he said, brushing off the sand. ‘Why's she such a baby?’

‘I'm not a baby,’ Paula wailed. ‘You're rotten!’

‘OK, OK,’ I said. ‘Enough. Adrian, clean up Topsy and give her back to Paula. And please ask your sister next time before you take her things. If you want to bury something, why not use your model dinosaurs? Dinosaurs are used to being buried: they've been at it for millions of years.’

‘Cor, yes, that's cool,’ Adrian said with renewed enthusiasm. ‘I'll dig in the garden for dinosaur fossils!’ On his hands and knees, he scooped Topsy up in the digger and deposited her in Paula's lap, and then headed for the freshly turned soil in a flowerbed that I had recently weeded. I thought that if Edna couldn't smooth over the sibling rivalry between Donna and her younger brothers and Donna did come to stay, she would be in very good company, and would soon feel most at home.

I made the three of us a sandwich lunch, which we ate in the garden under the shade of the tree; then I suggested to Adrian and Paula that we went to our local park for an hour or so. The park was about a ten-minute walk away, and Adrian wanted to take his bike and Paula her doll's pram. I asked Adrian to go to the shed at the bottom of the garden and get out the bike and doll's pram while I took in the dry washing and the lunch things, and closed the downstairs windows. Since my divorce, Adrian, in small ways, had become the man of the house, and although I would never have put on him or given him responsibility beyond his years, having little ‘man’ jobs to do had helped ease the blow of no longer having his father living with us, as did seeing him regularly.

It was quite safe for Adrian and Paula to go into the shed: anything dangerous like the shears, lawn feed and weedkiller was locked in a cupboard, and I had the key. Apart from being necessary for my own children's safety, this was an essential part of our ‘safer caring policy’, which was a document all foster carers had to draw up and follow, and detailed how the foster home was to be kept safe for everyone. Each year Jill, my support social worker, checked the house and garden for safety, as part of my annual review. The garden had to be enclosed by sturdy fencing, the side gate kept locked, drains covered and anything likely to be hazardous to children kept locked away. The safety checklist for the house itself grew each year. Apart from the obvious smoke alarms, stair gates (top and bottom) if toddlers were being fostered, the locked medicine cupboard high on the wall in the kitchen, and the plug covers or circuit breaker, there were also now less obvious requirements. The banister rails on the stairs had to be a set distance apart so that a small child couldn't get their head, arm or leg stuck in the gap; the glass in the French windows had had to be toughened in case a child ran or fell into them; and the thermostats on the radiators had to be set to a temperature that could never burn a young child's delicate skin. It is true to say that a foster carer's home is probably a lot safer than it would be if only the carer's own children were living there.

‘And don't forget to close the shed door, please, Adrian,’ I called after him. ‘We don't want that cat getting in again.’

‘Sure, Mum,’ he returned, for he remembered, as I did, the horrendous smell that had greeted us last week after a tomcat had accidentally got locked in overnight; the smell still hadn't completely gone, even after all my swabbing with disinfectant.

‘Sure, Mum,’ Paula repeated, emulating Adrian, having forgiven him. I watched as Adrian stopped and waited for Paula to catch up. He held her hand and continued down the garden, protectively explaining to her that she could wait outside the shed while he got her pram so that she wouldn't have to encounter the big hairy spiders that lurked unseen inside. Ninety per cent of the time Adrian and Paula got along fine, but like all siblings occasionally they squabbled.

Half an hour later we were ready to go. The bike and doll's pram, which we had brought in through the house to save unpadlocking the side gate, were in the hall. I had my mobile and a bottle of water each for the children in my handbag, and my keys for chub-locking the front door were in my hand. Then Paula said she wanted to do a wee now because she didn't like the toilets in the park because of the spiders. Adrian and I waited in the hall while she went upstairs, and when she returned five minutes later we were finally ready for off. I opened the front door, Adrian manoeuvred his bike out over the step, and Paula and I were ready to follow with her doll's pram when the phone on the hall table started ringing.

‘Adrian, just wait there a moment,’ I called, and with Adrian paused in the front garden and Paula waiting for me to lift the pram over the step I picked up the phone. ‘Hello?’

‘Is that Cathy Glass?’ It was a woman's voice with a mellow Scottish accent.

‘Speaking.’

‘Hello, Cathy. It's Edna Smith, Donna's social worker. I spoke to Jill earlier. I think you're expecting my call?’

‘Oh yes, hello Edna. I'm sorry, can you just wait one moment please?’ I covered the mouthpiece. ‘It's a social worker,’ I said to Adrian. ‘Come back inside for a minute.’ He left his bike on the front path and came in, while I helped Paula reverse her pram a little along the hall so that I could close the front door. ‘I won't be long,’ I said to the children. ‘Go into the lounge and look at a book for a few minutes.’ Adrian tutted but nevertheless nodded to Paula to follow him down the hall and into the lounge.

‘Sorry, Edna,’ I said, uncovering the mouthpiece. ‘We were just going out.’

‘I'm sorry. Are you sure it's all right to continue?’

‘Yes, go ahead.’ In truth, I could hardly say no.

‘Cathy, I'm in the car now, with Donna. She's been a bit upset and I'm taking her for a drive. I had hoped to come and visit you, just for a few minutes?’

‘Well, yes, OK. How far away are you?’

‘About ten minutes. Would that be all right, Cathy?’

‘Yes. We were only going to the park. We can go later.’

‘Thank you. We won't stay long, but I do like to do an initial introductory visit before a move.’ So Donna was being moved, I thought, and while I admired Edna's dedication, for doubtless this unplanned visit had disrupted her schedule as it had ours, I just wished it could have waited for an hour until after our outing. ‘I should like to move Donna to you this evening, Cathy,’ Edna added, ‘if that's all right with you and your family?’

Clearly the situation with Donna and her brothers had deteriorated badly since she had spoken to Jill. ‘Yes, we'll see you shortly, then, Edna,’ I confirmed.

‘Thank you, Cathy.’ She paused. ‘And Cathy, you might find Donna is a bit upset, but normally she is a very pleasant child.’

‘OK, Edna. We'll look forward to meeting her.’

I replaced the receiver and paused for a minute in the hall. Edna had clearly been guarded in what she had said, as Donna was in the car with her and able to hear every word. But the fact that everything was happening so quickly said it all. Jill had phoned only an hour and a half before, and since then Edna had seen the need to remove Donna from the foster home to diffuse the situation. And the way Edna had described Donna — ‘a bit upset, but normally … a very pleasant child’ — was a euphemism I had no difficulty in interpreting. It was a case of batten down the hatches and prepare for a storm.

Adrian and Paula had heard me finish on the phone and were coming from the lounge and down the hall, ready for our outing. ‘Sorry,’ I said. ‘We'll have to go to the park a bit later. The social worker is bringing a girl to visit us in ten minutes. Sorry,’ I said again. ‘We'll go to the park just as soon as they've gone.’

Unsurprisingly they both pulled faces, Adrian more so. ‘Now I've got to get my bike in again,’ he grumbled.

‘I'll do it,’ I said. ‘Then how about I get you both an ice cream from the freezer, and you can have it in the garden while I talk to the social worker?’ Predictably this softened their disappointment. I pushed Paula's pram out of the way and into the front room, and then brought in Adrian's bike and put that in the front room too. I went through to the kitchen and took two Cornettos from the freezer, unwrapped them, and took a small bite from each before presenting them to the children in the lounge. They didn't comment — they were used to my habit of having a crafty bite. I opened the French windows and, while Adrian and Paula returned to the garden to eat their ice creams in the shade of the tree, I went quickly upstairs to check what, tonight, would be Donna's bedroom. Foster carers and their families get used to having their plans changed and being adaptable.

Chapter Two So Dreadfully Sad (#ulink_82220635-c710-5006-a512-de6b3f7de155)

No sooner had I returned downstairs than the front door bell rang. Resisting the temptation to peek through the security spy-hole for a stolen glance at my expected visitors, I opened the door. Edna and Donna stood side by side in the porch, and my gaze went from Edna, to Donna. Two things immediately struck me about Donna: firstly that, as Edna has said, she was a big girl, not overweight but just tall for her age and well built, and secondly that she looked so dreadfully, dreadfully sad. Her big brown eyes were downcast and her shoulders were slumped forward as though she carried the weight of the world on them. Without doubt she was the saddest-looking child I had ever seen — fostered or otherwise.

‘Come in,’ I said, welcomingly and, smiling, I held the door wide open.

‘Cathy, this is Donna,’ Edna said in her sing-song Scottish accent.

I smiled again at Donna, who didn't look up. ‘Hello, Donna,’ I said brightly. ‘It's nice to meet you.’ She shuffled into the hall and found it impossible to even look up and acknowledge me. ‘The lounge is straight ahead of you, down the hall,’ I said to her, closing the front door behind us.

Donna waited in the hall, head down and arms hanging loosely at her side, until I led the way. ‘This is nice, isn't it?’ Edna said to Donna, trying to create a positive atmosphere. Donna still didn't say anything but followed Edna and me into the lounge. ‘What a lovely room,’ Edna tried again. ‘And look at that beautiful garden. I can see swings at the bottom.’

The French windows were open and to most children it would have been an irresistible invitation to run off and play, happy for the chance to escape adult conversation, but Donna kept close to her social worker's side and didn't even look up.

‘Would you like to go outside?’ I asked Donna. ‘My children, Adrian and Paula, are out there having an ice cream. Would you like an ice cream?’ I looked at her: she was about five feet tall, only a few inches shorter than me, and her olive skin and dark brown hair suggested that one of her parents or grandparents was Afro-Caribbean. She had a lovely round face, but her expression was woeful and dejected; her face was blanked with sadness. I wanted to take her in my arms and give her a big hug.

‘Would you like an ice cream?’ Edna repeated. Donna hadn't answered me or even looked up to acknowledge my question.

She imperceptibly shook her head.

‘Would you like to join Adrian and Paula in the garden for a few minutes, while I talk to Cathy?’ Edna asked.

Donna gave the same slight shake of her head but said nothing. I knew that Edna would really have liked Donna to have gone into the garden so that she could discuss her situation candidly with me, which she clearly couldn't do if Donna was present. More details about Donna's family and what had brought her into care would follow with the placement forms Edna would bring with her when she moved Donna. But it would have been useful to have had some information now so that I could prepare better for Donna's arrival, anticipate some of the problems that might arise and generally better cater for her needs. Donna remained standing impassively beside Edna at the open French windows and didn't even raise her eyes to look out.

‘Well, shall we sit down and have a chat?’ I suggested. ‘Then perhaps Donna might feel more at home. It is good to meet you, Donna,’ I said again, and I lightly touched her arm. She moved away, as though recoiling from the touch. I thought this was one hurting child, and for the life of me I couldn't begin to imagine what ‘sibling rivalry’ had led to this; clearly there was more to it than the usual sibling strife.

‘Yes, that's a good idea. Let's sit down,’ Edna said encouragingly. I had taken an immediate liking to Edna. She was a homely middle-aged woman with short grey hair, and appeared to be one of the old-style ‘hands-on’ social workers who have no degree but years and years of practical experience. She sat on the sofa by the French windows, which had a good view of the garden, and Donna sat silently next to her.

‘Can I get you both a drink?’ I asked.

‘Not for me, thanks, Cathy. I took Donna out for some lunch earlier. Donna, would you like a drink?’ She turned sideways to look at her.

Donna gave that same small shake of the head without looking up.

‘Not even an ice lolly?’ I tried. ‘You can eat it in here with us if you prefer?’

The same half-shake of the head and she didn't move her gaze from where it had settled on the carpet, a couple of feet in front of her. She was perched on the edge of the sofa, her shoulders hunched forward and her arms folded into her waist as though she was protecting herself.

‘Perhaps later,’ Edna said.

I nodded, and sat on the sofa opposite. ‘It's a lovely day,’ I offered.

‘Isn't it just,’ Edna agreed. ‘Now, Cathy, I was explaining to Donna in the car that we are very lucky to have found you at such short notice. Donna has been rather unhappy where she has been staying. She came into care a month ago with her two younger brothers so that her mummy could have a chance to sort out a few things. Donna has an older sister, Chelsea, who is fourteen, and she is staying with mum at present until we find her a suitable foster placement.’ Edna met my eyes with a pointed look and I knew that she had left more unsaid than said. With Donna present she wouldn't be going into all the details, but it crossed my mind that Chelsea might have refused to move. I doubted Edna would have taken three children into care and left the fourth at home, but at fourteen it was virtually impossible to move a child without their full cooperation, even if it was in their best interest.

‘Donna goes to Belfont School,’ Edna continued, ‘which is about fifteen minutes from here.’

‘Yes, I know the school,’ I said. ‘I had another child there once, some years ago.’

‘Excellent.’ Edna glanced at Donna, hoping for some enthusiasm, but Donna didn't even look up. ‘Mrs Bristow is still the head there, and she has worked very closely with me. School doesn't start again until the fourth of September and Donna will be in year five when she returns.’ I did a quick calculation and realised that Donna was in a year below the one for her age. ‘Donna likes school and is very keen to learn,’ Edna continued positively. ‘I am sure that once she is settled with you she will catch up very quickly. The school has a very good special needs department and Mrs Bristow is flexible regarding which year children are placed in.’ From this I understood that Donna had learning difficulties and had probably (and sensibly) been placed out of the year for her age in order to better accommodate her learning needs. ‘She has a good friend, Emily, who is in the same class,’ Edna said, and she looked again at Donna in the hope of eliciting a positive response, but Donna remained hunched forward, arms folded and staring at the carpet.

‘I'll look forward to meeting Emily,’ I said brightly. ‘And perhaps she would like to come here for tea some time?’

Edna and I both looked at Donna, but she remained impassive. Edna touched her arm. ‘It's all right, Donna. You are doing very well.’

I looked at Donna and my heart went out to her: she appeared to be suffering so much, and in silence. I would have preferred her to have been angry, like so many of the children who had come to me. Shouting abuse and throwing things seemed a lot healthier than internalising all the pain, as Donna was. Huddled forward with her arms crossed, it was as though Donna was giving herself the hug of comfort she so badly needed. Again I felt the urge to go and sit beside her and hug her for all I was worth.

At that moment Adrian burst in through the open French windows, quickly followed by Paula. ‘I've brought in my wrapper,’ he said, offering the Cornetto wrapper; then he stopped as he saw Edna and Donna.

‘Good boy,’ I said. ‘Adrian, this is Donna, who will be coming to stay with us, and this is her social worker, Edna.’

‘Hello, Adrian,’ Edna said with her warm smile, putting him immediately at ease.

‘Hi,’ he said.

‘And you must be Paula?’ Edna said.

Paula grinned sheepishly and gave me her Cornetto wrapper.

‘How old are you?’ Edna asked.

‘I'm ten,’ Adrian said, ‘and she's six.’

‘I'm six,’ Paula said, feeling she was quite able to tell Edna how old she was herself. Donna still had her eyes trained on the floor; she hadn't even looked up as Adrian and Paula had bounced in.

‘That's lovely, isn't it, Donna?’ Edna said, trying again to engage Donna; then, addressing Adrian and Paula, ‘Donna has two younger brothers, aged seven and six. It will be nice for her to have someone her own age to play with.’ This clearly didn't impress Adrian, for at his age girls were something you dangled worms in front of to make them scream but didn't actually play with. And given the difference in size — Donna was a good four inches taller than Adrian — she would be more like an older sister than one of his peer group.

‘You can play with me now,’ Paula said, spying a golden opportunity for some girl company.

‘That's a good idea,’ Edna said to Paula. ‘Although we won't be staying long — we've got a lot to do.’ Placing her hand on Donna's arm again, Edna said, ‘Donna, you go in the garden with Paula for a few minutes, and then we will show you around the house and go.’

I looked at Donna and wondered if she would follow what had been an instruction from Edna rather than a request. Edna, Adrian and Paula looked too.

‘Come on,’ Paula said. ‘Come and play with me.’ She placed her little hand on the sleeve of Donna's T-shirt and gave it a small tug. I noticed Donna didn't pull away.

‘Go on, Donna,’ Edna encouraged. ‘A few minutes in the garden and then we must go.’

‘Come on, Donna,’ Paula said again and she gave her T-shirt another tug. ‘You can push me on the swing.’

With her arms still folded across her waist and not looking up, Donna slowly stood. She was like a little old woman dragging herself to do the washing up rather than a ten-year-old going to play in the garden.

‘Good girl,’ Edna said. We both watched as, with her head lowered, Donna allowed Paula to gently ease her out of the French windows and into the garden. Adrian watched, mesmerised, and then looked at me questioningly. I knew what he was thinking: children didn't usually have this much trouble going into the garden to play.

‘Donna is a bit upset,’ I said to him. ‘She'll be all right. You can go and play too.’

He turned and went out, and Edna and I watched them go down the garden. Adrian returned to his archaeological pursuits in the sandpit while Paula, still holding Donna's T-shirt, led her towards the swings.

‘Paula will be fine with Donna,’ Edna said, reading my thoughts. ‘Donna is good with little ones.’ While I hadn't thought that Donna would hit Paula, she was so much bigger, and it had crossed my mind that all her pent-up emotion could easily be released in any number of ways, including physical aggression. Edna gave a little sigh and returned to the sofa. I sat next to her so that I could keep an eye on what was happening down the garden.

‘I've had a very busy morning,’ Edna said. ‘Mary and Ray, Donna's present carers, phoned me first thing and demanded that I remove Donna immediately. I've had to cancel all my appointments for the whole day to deal with this.’

I nodded. ‘Donna seems very sad,’ I said.

‘Yes.’ She gave another little sigh. ‘Cathy, I really can't understand what has gone so badly wrong. All the carers are saying is that Donna is obsessively possessive with her brothers, Warren and Jason, and won't let Mary and Ray take care of them. Apparently they've had to physically remove her more than once from the room so that they could take care of the boys. Donna is a big girl and I understand there have been quite a few ugly scenes. Mary showed me a bruise on her arm, which she said Donna had done last night when she and Ray had tried to get her out of the bathroom so that the boys could be bathed. They are experienced carers, but feel they can't continue to look after Donna.’

I frowned, as puzzled as Edna was, for the description she had just given me of Donna hardly matched the silent withdrawn child who had slunk in unable even to look at me.

‘The boys are staying with Mary and Ray for now,’ Edna continued. ‘They all go to the same school, so you will meet Ray and Mary when school returns. They are both full-time carers; Ray took early retirement. They are approved to look after three children and have done so in the past, very successfully, so I really don't know what's gone wrong here.’

Neither did I from what Edna was saying, but it wasn't my place to second guess or criticise. ‘Looking after three children has probably been too much,’ I said. ‘It's a lot of work looking after one, let alone three, particularly when they have just come into care and are upset and still adjusting.’

Edna nodded thoughtfully and glanced down the garden, as I did. Donna was pushing Paula on the swing, but whereas Paula was in her element and squealing with delight, Donna appeared to be performing a mundane duty and was taking no enjoyment whatsoever in the task.

‘Is Donna all right doing that?’ I asked. ‘She doesn't have to push Paula on the swing.’

‘I'm sure she is fine, Cathy. She's showing no enthusiasm for anything at present.’ Edna returned her gaze to me. ‘I've been working with Donna's family for three years now. I have really tried to keep them together, but her mum just couldn't cope. I put in place all the support I could. I have even been going round to their home and helping to wash and iron the clothes, and clean the house, but by my next visit it's always filthy again. I had no alternative but to bring them into care.’ Edna looked at me with deep regret and I knew she was taking it personally, feeling that she had failed in not keeping the family together, despite all her efforts. Edna was certainly one conscientious and dedicated social worker, and Donna was very lucky to have her.

‘You obviously did all you could,’ I offered. ‘There can't be many who would have done all that,’ and I meant it.

Edna looked at me. ‘Donna's family has a long history with social services, and mum herself was in and out of care as a child. Donna's father is not supposed to be living at the family home but he was there only last week when I made a planned visit. The front door had been broken down and Rita, Donna's mum, said Mr Bajan, Donna's father, had smashed his way in. But he was sitting happily in a chair with a beer when I arrived and Rita wasn't exactly trying to get him out. I made arrangements to have the door repaired straight away, because there was no way they could secure the house and Chelsea is still living there.’

I nodded. ‘What a worry for you!’

‘Yes, it is. Chelsea hasn't been in school for months,’ Edna continued, shaking her head sadly. ‘And she told me that Mr Bajan hadn't been taking his medication again. He's been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic, and if he doesn't take his medication he becomes very delusional and sometimes violent. I explained to him that he must keep taking it and that if he didn't I would have to have him sectioned again. He was very cooperative, but I don't suppose he will remember what I said. When he is taking the tablets he functions normally, and then because he feels better he thinks he doesn't need the tablets any more, he stops taking them, and becomes ill again.’

I thought what a lot Donna and her family had had to cope with, and I again glanced down the garden, where Donna was still laboriously pushing Paula on the swing.

‘Donna's mum, Rita, has a drink problem,’ Edna continued, following my gaze, ‘and possibly drug abuse, although we don't know for sure. The house is absolutely filthy, a health hazard, and I've had the council in a number of times to fumigate it. Rita can't keep it clean. I've shown her how to clean, many times, but there's always cat and dog mess on the floors, as they encourage strays in. Instead of clearing up the mess, they throw newspaper down to cover it. The whole house stinks. They have broken the new bath I had put in, and the cooker I gave Rita a grant for has never been connected. There is no sign of the table and chairs I had delivered, nor the beds I ordered. The children were sleeping on an old mattress — all of them on one. There's nothing on the floors but old newspaper, and most of the windows have been smashed at one time or another. Rita phones me each time one is broken and I have to make arrangements to have it repaired. There is never any food in the house, and Warren and Jason, Donna's brothers, were running riot on the estate. Neighbours have repeatedly complained about the family, and also about the screaming and shouting coming from the house when Mr Bajan is there.’

I nodded again, and we both looked down the garden, where Donna was still pushing Paula on the swing.

‘Mr Bajan is Donna's father and also the father of Warren and Jason, according to the birth certificates, although I have my doubts,’ Edna said. ‘Chelsea has a different father who has never been named, but she looks like Donna — more than Donna looks like the boys. Mr Bajan has dual heritage and his mother is originally from Barbados. She lives on the same estate and has helped the family as much as she can. I asked her if she could look after the children, but at her age she didn't feel up to it, which is understandable. She's not in the best of health herself and goes back to visit her family in Barbados for some of the winter. She's a lovely lady, but like the rest of the family blames me for bringing the children into care.’

Edna paused and let out another sigh. ‘But what could I do, Cathy? The family situation was getting worse, not better. When I first took Donna and her brothers into care they all had head lice, and fleas, and the two boys had worms. I told their mother and she just shrugged. I can't seem to get through to Rita.’

‘So what are the long-term plans for the children?’ I asked.

‘We have ICOs’ — Edna was referring to Interim Court Orders — ‘for Donna and the boys. I'll apply to the court to renew them, and then see how it goes. Having the children taken into care might give Rita the wake-up call she needs to get herself on track. I hope so; otherwise I'll have no alternative but to apply for a Full Care Order and keep the children in long-term foster care. I'm sure Rita loves her children in her own way but she can't look after them or run a house. I wanted to remove Chelsea too, but she is refusing, and in some ways it's almost too late. Chelsea is rather a one for the boys, and mum can't see that it's wrong for a fourteen-year-old to be sleeping with her boyfriend. In fact Rita encourages it — she lets Chelsea's boyfriend sleep with her at their house and has put Chelsea on the pill. I've told Rita that under-age sex is illegal but she laughs. Rita was pregnant with Chelsea at fifteen and can't see anything wrong in it. She's spent most of her life having children — apart from Chelsea, Donna, and the boys she's had three miscarriages to my knowledge.’

I shuddered. ‘How dreadfully sad.’

‘It is. It would be best if Rita didn't have any more wee babies and I'm trying to persuade her to be sterilised, but I'm not getting anywhere at present. She has learning difficulties like Donna and Chelsea. Warren and Jason are quite bright — in fact Warren is very bright. He taught himself to read as soon as he started school and had access to books.’

‘Really? That's amazing,’ I said, impressed.

Edna nodded, and then looked at me carefully. ‘You won't give up on Donna, will you, Cathy? She's a good kid really, and I don't know what's gone wrong.’

‘No, of course I won't,’ I reassured her. ‘I'm sure she'll settle. I've taken an immediate liking to Donna and so has Paula by the look of it. ’ We both glanced down the garden again. ‘Although from what you've said Donna is going to miss her brothers,’ I added.

‘I think Donna is blaming herself for the three of them being taken in care,’ Edna said. ‘Donna was the one who looked after Warren and Jason, and tried to do the housework. Chelsea was always out, and mum sleeps for most of the day when she's been drinking. But you can't expect a ten-year-old to bring up two children and run a house. Donna blames herself, and the rest of the family blame me. Rita hit me the last time I was there. I've told her if she does it again I'll call the police and have her arrested.’ Not for the first time I wondered at the danger social workers were expected to place themselves in as a routine part of their jobs.

We both looked down the garden. Paula was off the swing now, talking to Donna, who was standing with her arms folded, head cocked slightly to one side. She had the stance of a mother listening to her child with assumed patience, rather than that of a ten-year-old.

‘Donna and her brothers will be seeing their parents three times a week,’ Edna said. ‘Monday, Wednesday and Friday, five to six thirty, although I've cancelled tonight's contact. I'm supervising the contact at our office in Brampton Road for now, until a space is free at the family centre. Do you know where that is?’

‘Yes.’ I nodded.

‘Will you be able to take and collect Donna for contact?’

‘Yes, I will.’

‘Good. Thanks. Rita is angry but you shouldn't have to meet her. I'll bring the placement forms with me this evening when I move Donna. It's going to be after six o'clock by the time we arrive. Ray wants to be there when Donna leaves in case there is a problem. He doesn't finish work until five thirty. And Mary has asked that I keep Donna away for the afternoon. She said she will pack her things and have them ready for five thirty.’ Edna sighed again. ‘Donna will have to come with me to the office for the afternoon, and I'll find her some crayons and paper to keep her busy. Really, Cathy, she's a good girl.’

‘I'm sure she is,’ I said. ‘It's a pity she can't come with us to the park this afternoon.’ But we both knew that couldn't happen, as until all the placement forms had been signed that evening I was not officially Donna's foster carer.

‘I think that's all then, Cathy,’ Edna said. ‘I can't think of anything else at present.’

‘Food?’ I asked. ‘Does Donna have any special dietary requirements?’

‘No, and she likes most things. There are no health concerns either. Well, not physical, at least.’ I looked at her questioningly and she shrugged. ‘Mary said she thought Donna was suffering from OCD.’

‘OCD?’ I asked.

‘Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.’

‘Oh, I see,’ I said, surprised. ‘Why does she think that?’

‘Apparently she keeps washing her hands.’ Edna gave one of her characteristic sighs. ‘I don't know, Cathy. You seem pretty sensible. I'm sure you'll notice if there is anything untoward.’

‘It's probably just nerves,’ I offered.

‘Yes. Anyway, we'll leave you to go to the park now. Thanks for taking Donna and sorry it's such short notice. I know I have to phone Jill and update her later.’

‘Yes please. Would Donna like to look around the house before you go?’

Edna nodded. ‘We'll give her a tour, but don't expect much in the way of response.’

‘No,’ I said, smiling. ‘Don't worry. I'm sure she'll soon thaw out when she moves in.’ Edna seemed to need more reassurance than I did, and I thought that over the three years she had worked with the family she had probably built up quite a bond with the children. She appeared to have a particularly soft spot for Donna, and I could see why: Donna was crying out for love and attention, although she didn't know it.

I stood and went to the French windows. ‘Paula!’ I called from the step. ‘Donna has to go now.’

I saw Paula relay this to Donna, who was still standing, arms folded and head lowered, not looking at Paula. Donna didn't make a move, so I guessed Paula repeated it; then I watched as Paula slipped her hand into Donna's and began to lead her up the garden and towards the house. It was sad and almost comical to see little Paula in charge of, and leading, this big girl, and Donna walking a pace behind her, allowing herself to be led.

‘Good girls,’ I said, as they arrived.

Paula grinned but Donna kept her eyes down and carefully trained away from mine.

‘Cathy is going to show us around now, Donna,’ Edna said brightly. ‘Then we must be going.’

‘Can I come to show Donna around?’ Paula asked.

‘Yes, of course.’ I smiled at her, and looked at Donna, but she didn't look up, and sidled closer to Edna, taking comfort in her familiar presence in what was for her an unfamiliar house. I could see that Donna thought a lot of Edna, as Edna did of Donna.

I gave them a quick tour of the downstairs of the house and pointed out where all the toys were. As we entered each room Edna said, ‘This is nice, isn't it, Donna?’ trying to spark some interest. Donna managed a small nod but nothing else, and I wasn't expecting any more, for clearly and unsurprisingly she was finding all this very difficult. She didn't raise her eyes high enough to see any of the rooms we went into. As we entered what was to be her bedroom and Edna said, ‘This is nice, isn't it?’ Donna managed a small grunt, and I thought for a second she was going to look up, but instead she snuggled closer to Edna, and it was left to Paula to comment on the view out of the bedroom window.

‘Look, you can see the swings in the garden,’ Paula called, going over to the window. ‘And next door's garden. They've got children and they come round and play sometimes.’

Donna gave a small nod, but I thought she looked sadder than ever. I wondered if that was because she was going to have to settle into what would be her third bedroom in under a month; or perhaps it was because of the mention of ‘children’ and the realisation that she wouldn't be playing with her brothers on a daily basis.

‘It will look lovely when you have your things in here, Donna,’ Edna said encouragingly. Donna didn't say anything and Edna looked at me. ‘Thank you for showing us around, Cathy. I think it's time we went now. We've got a lot to do.’

Edna led the way out of the bedroom with Donna at her heels, and Paula and me following. Paula tucked her hand into mine and gave it a squeeze; I looked at her.

‘Doesn't she like her bedroom?’ Paula asked quietly, but not quietly enough; I knew Donna had heard.

‘Yes, but I'm sure it must seem very strange to begin with. You're lucky: you've never had to move. Don't worry, we'll soon make her feel welcome.’

Paula came with me to the front door to see Edna and Donna out. ‘Say goodbye to Adrian for me,’ Edna said. ‘Donna and I will see you as soon after six o'clock as we can make it. Is that all right with you?’

‘Yes. We'll be looking forward to it.’

‘Bye, Donna,’ Paula said as I opened the door and they stepped out. ‘See you later.’

Edna looked back and smiled, but Donna kept going. Once they had disappeared along the pavement towards Edna's car, I closed the door and felt relief run through me. Although Donna wasn't the disruptive child I had thought she might be, kicking, screaming and shouting abuse, the weight of her unhappiness was so tangible it was as exhausting as any outward disturbing or challenging behaviour.

Paula followed me down the hall and towards the French windows to call Adrian in. ‘Do you think Donna will want to play with me?’ she asked.

‘Yes, I am sure she will, love. She's a bit shy at present.’

‘I'll make her happy playing with me,’ she said. ‘We can have lots of fun.’

I smiled and nodded, but I thought that it would be a long time before Donna had genuine and heartfelt fun, although she might well go through the motions and cooperate with Paula, as she had done when pushing the swing. Despite all Edna had told me about Donna's family, the circumstances for bringing her and her brothers into care and now moving her to me, I was really none the wiser as to why she was having to move and why she was so withdrawn. But one thing I was certain of was that Donna carried a heavy burden in her heart which she wasn't going to surrender easily.

Chapter Three Donna (#ulink_2f0fe187-149d-50bc-8798-11939a87c44d)

With Adrian pushing his bike along the pavement, and Paula her doll's pram, we made a somewhat faltering journey to our local park. I always insisted that Adrian wheel his bike until we were away from the road and in the safety of the park with its cycle paths. Paula stopped every so often to readjust the covers around the ‘baby’ in the pram, although in truth, and as Adrian pointed out with some relish, it was so hot that it hardly mattered that baby was uncovered as ‘it’ was hardly likely to catch cold.

‘Not again,’ Adrian lamented as our progress was once more interrupted by Paula stopping and seeing to baby. ‘Give it to me,’ he said at last, ‘and I'll tie it to my handlebars. Then we can get there.’

‘It's not an it,’ Paula said, rising to the bait.

But that was normal brother and sister teasing, and I thought a far cry from whatever had been happening between Donna and her brothers. As nothing Edna had said had explained how the situation between Donna and her brothers had deteriorated to the point of her having to move, I came back to the possibility it could be an excuse from her carers. Perhaps Mary and Ray hadn't been able to cope with having three children, all with very different needs and who would have been very unsettled, and as experienced carers they had felt unable to simply admit defeat and say they couldn't cope, and had seized upon some sibling jealousy to effect the move. I didn't blame them, although I hoped that Donna hadn't been aware that she was the ‘culprit’; Edna had referred to the situation as Donna being ‘upset’, which shouldn't have left her feeling in any way guilty.

Once in the park, Adrian cycled up and down the cycle paths, aware that, as usual, he had to stay within sight of me. ‘If you can see me, then I can see you,’ I said to him as I said each time we brought his bike to the park. Even so, I had one eye on him while I pushed Paula on the swings and kept my other eye on ‘the baby’ in the pram as Paula had told me to.

I thought of Donna as Paula swung higher and higher in front of me with little whoops of glee at each of my pushes. I thought of Donna's profile as I had seen her at the bottom of our garden, slumped, dejected and going through the motions of entertaining Paula. I would have to make sure that Paula didn't ‘put on’ Donna, for I didn't want Donna to feel she had to entertain or play with Paula, or Adrian for that matter, although this was less likely. Something in Donna's compliance, her malleability, had suggested she was used to going along with others' wishes, possibly to keep the peace.

Paula swapped the swing for the see-saw, and I sat on one end and she on the other. As I dangled her little weight high in the air to her not-very-convincing squeals of ‘Put me down’, I felt a surge of hope and anticipation, an optimism. I was sure that when Donna came to stay with us, given the time and space, care and attention she clearly so badly needed, she would come out of her shell and make huge progress, and I could visualise her coming here to play. I also thought that Donna was going to be a lot easier to look after than some of the children I had fostered. She didn't come with behavioural difficulties — kicking or screaming abuse, for instance — and certainly wasn't hyperactive; and if Mary did have a bruise on her arm, I now smugly assumed it was because she and Ray had mishandled the situation when they had been trying to bath the boys. Had they allowed Donna to help a little, instead of trying to forcibly remove her from the bathroom, I was sure the whole episode could have been defused. Like so many situations with children, fostered or one's own, it was simply, I thought, a matter of handling the child correctly — giving choices and some responsibility, so that the child felt they had a say in their lives.

I had a lot to learn!

We ate at 5.00 p.m., earlier than usual, so that I could clear away and be ready for Donna's expected arrival soon after 6.00. We'd had chicken casserole and I had plated up some for Donna, which I would re-heat in the microwave if she was hungry. After she had spent the afternoon with Edna in her office they were returning to Mary and Ray's only to collect her belongings and say goodbye, so there was a good chance she wouldn't have had dinner. Children always feel better once they've eaten their first meal in the house, and spent their first night in their new bedroom. I had also bathed Paula early, and she was changed into her pyjamas; her usual bedtime was between 7.00 and 7.30, but that was when I would be directing my attention to Donna tonight. Adrian, at ten, was used to taking care of his own bath or shower, and could be left to get on with it — he didn't need or want me to be present any more.

At 6.00 p.m. the children's television programmes had finished; the French windows were still wide open on to the glorious summer evening and Adrian was sitting on the bench on the patio, playing with his hand-held Gameboy with Paula beside him, watching. I'd told Paula that she could go outside again, but as she'd had her bath I didn't want her playing in the sandpit and in need of another bath. I was sitting on the sofa by the French windows with the television on, vaguely watching the six o'clock news. I doubted Edna and Donna would arrive much before 6.30, by the time they had said their goodbyes to Mary and Ray (and Warren and Jason) and loaded up the car with Donna's belongings. I wondered how her brothers were taking Donna's sudden departure. They had, after all, been together for all their lives, albeit not in very happy circumstances, so they would be pretty distressed, I thought.

Jill, my support social worker, was present whenever possible when a child was placed with me; however, I wasn't expecting her this evening. She had left a message on the answerphone while we'd been at the park, saying that she'd been called away to an emergency with new carers in a neighbouring county, and that if anything untoward arose and I needed her advice, to phone her mobile. I didn't think I would need to phone, as the placement of Donna with me would be quite straightforward; Edna was very experienced and would bring all the forms that were needed with her.

Five minutes later the doorbell rang and my heart gave a funny little lurch. I immediately stood and switched off the television. Welcoming a new child (or children) and settling them in is always an anxious time, and not only for the child. I must have done it over thirty times before but there was still a surge of worry, accompanied by anxious anticipation, as I wanted to do my best to make the child feel at home as quickly as possible. Adrian and Paula had heard the doorbell too; Adrian stayed where he was, intent on his Gameboy, while Paula came in.

‘Is that Donna?’ Paula asked.

‘I think so.’

Paula came with me down the hall, and I opened the front door. I could tell straight away that parting hadn't been easy: Donna was clearly upset. She had a tissue in her hand and had obviously been crying; she looked sadder than ever and my heart went out to her. Edna looked glum too, and absolutely exhausted.

‘Come in,’ I said, standing aside to let them pass.

‘Thank you, Cathy,’ Edna said, placing her hand on Donna's arm to encourage her forward. ‘We'll sit down for a while, and then I'll unpack the car.’

‘Go on through to the lounge,’ I said as they stepped passed me into the hall, and I closed the door. Paula walked beside Donna and tried to take her hand, but Donna pulled it away. I mouthed to Paula not to say anything because Donna was upset.

‘You go with Adrian for now,’ I said to Paula as we entered the lounge. She returned to sit beside him on the bench outside, where he was still engrossed in his Gameboy.

‘It's one of those Mario games,’ I said to Edna as she glanced out through the French windows at Adrian. Edna smiled and nodded. Donna had sat close beside Edna on the sofa and her chin was so far down that it nearly rested on her chest.

‘Is everything all right?’ I asked Edna.

She nodded again, but threw me a look that suggested they had had a rough time and that she would tell me more later, not in front of Donna. ‘Mary and Ray gave Donna a goodbye present,’ Edna said brightly, glancing at Donna.

‘That's nice. Can I have a look?’ I asked Donna. Children are usually given a leaving present by their foster carers, and also a little goodbye party, although I assumed that hadn't happened here. Donna was clutching a small bright red paper bag on her lap, together with the tissue she'd used to wipe her eyes. ‘What did you get?’ I tried again, but she shrugged and made no move to show me. ‘Perhaps later,’ I said. ‘Would you like a drink, Donna? Or something to eat? I've saved you dinner if you want it.’

She gave that slight shake of the head, so I assumed she didn't want either now.

‘I'll do the paperwork,’ Edna said, ‘and then I'll leave Donna to settle in. She's had a very busy day and I expect she'll want an early night.’

I nodded. ‘What time do you usually go to bed, Donna?’

Edna glanced at her and then at me. ‘I'm not sure, but she's ten, so I would think eight o'clock is late enough, wouldn't you?’

‘Yes,’ I agreed. ‘That sounds about right. Adrian is the same age and usually goes up around eight and then reads for a bit.’ I looked at Donna as I spoke, hoping I might elicit some response; it felt strange and uncomfortable talking about a girl of her age without her actually contributing.

Edna took an A4 folder from her large shoulder bag and, opening it, removed two sets of papers, each paper-clipped in one corner. ‘I think I've already told you most of what is on the Essential Information Form,’ she said, flipping through the pages and running her finger down the typing. ‘I've only included the names and contact details of Donna's immediate family; there are aunts and uncles, but Donna sees them only occasionally. She had a medical when she first came into care and everything was fine. Also Mary and Ray took her to the dentist and optician, and that was all clear too.’ It is usual for a child to have these check-ups when they first come into care.

‘That's good,’ I said, and I glanced at Donna, who still had her head down. She'd cupped the little red bag containing the present protectively in her hands as if it was her most treasured possession in the world.

Edna checked down the last pages of the Essential Information Form, and then leant forward and handed it to me. This would go into the file I would start on Donna, as I had to for all the children I looked after, together with the paperwork I would gradually accumulate while Donna stayed with me, and also the daily log which I had to keep and which Jill inspected regularly when she visited.

‘The Placement Agreement forms are complete,’ Edna said, flipping through the second set of forms. ‘I checked them before we left the office.’ She peeled off the top sheets and, taking a pen from her bag, signed at the foot of the last page. She did the same for the bottom set of forms, which was a duplicate of the top set, and then passed both sets of forms to me. I added my signature beneath hers on both copies and passed one set back. The Placement Agreement gave me the legal right to foster Donna and I was signing to say I agreed to do this and to work to the required standard. One copy would be kept by the social services and my copy would go in my file.

‘Nearly finished,’ Edna said, turning to Donna.

I glanced through the open French windows at Paula and Adrian, sitting side by side on the bench. Adrian was still intent on his Gameboy and Paula was looking between the game and Donna, hoping Donna might look up and make eye contact.

‘Here's Donna's medical card,’ Edna said, passing a printed card to me. ‘Will you register her at your doctor's, please? She's outside the catchment area of Mary and Ray's GP.’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘I think that's about it then,’ Edna said, closing the folder and returning it to her bag. She placed her bag beside the sofa, glanced first at Donna and then looked at me. ‘Do you have any plans for the weekend, Cathy?’

‘Not especially. I thought we would have a relaxing weekend, and give Donna a chance to settle in. I will have to pop up to the supermarket tomorrow for a few things. Then on Sunday we could go to a park; the weather is supposed to be good.’

‘That sounds nice,’ Edna said. ‘Donna is good at shopping. She likes to help, don't you, Donna?’ We both looked at Donna and she managed to give that almost imperceptible nod. ‘You will be able to tell Cathy what your favourite foods are when you go shopping,’ Edna continued, trying to spark some interest. ‘I am sure Cathy will let you have some of them.’

‘Absolutely,’ I agreed. ‘You can help me choose, Donna.’

Edna's gaze lingered on Donna and I knew she was finding it difficult to make a move to leave. I wondered if Donna had been this quiet and withdrawn all afternoon, while she'd been with Edna at the office. Sitting forward, Edna said, ‘OK, Cathy, could you give me a hand unpacking the car then, please?’

‘Yes, of course.’ I stood and went to the French windows. ‘I'm just helping Edna unload the car,’ I said to Adrian and Paula. ‘You're all right there for now, aren't you?’

They nodded, Adrian without looking up from his game and Paula with her eyes going again to Donna.

‘You can stay there, Donna,’ Edna said, ‘or you can go in the garden if you like with Paula and Adrian.’

Donna shrugged without looking up, and Edna left the sofa and began towards the lounge door. ‘I'll come back in to say goodbye,’ she said, pausing and turning to look at Donna. Donna shrugged again, almost with indifference, as though it didn't matter if Edna said goodbye or not; but I knew for certain that it did matter. The poor girl had spent the last hour saying goodbye — to Warren and Jason, to Mary and Ray, and now to Edna. I could only guess at what must be going through her mind as her social worker, to whom she was obviously very close, and with whom she had spent all day, was about to depart and leave her with strangers, albeit ones with good intentions.

I followed Edna down the hall and she stood aside to allow me to open the front door. She gave one of her little heartfelt sighs. ‘I'm sure Donna will be fine by the end of the weekend,’ she said. ‘I'll phone on Monday and arrange to visit next week.’

‘I'll look after her, Edna,’ I reassured her. ‘Don't worry. Has she been this quiet all afternoon?’

‘She wasn't too bad until we went to say goodbye.’ Edna lowered her voice and leant towards me in confidence. ‘It was awful at Mary and Ray's. Donna was so upset to be leaving Warren and Jason, but the boys couldn't have cared less.’

‘Really?’ I said, shocked. ‘Why?’

‘I don't know. I had to make them say goodbye. They told Donna to her face that they were pleased she was going, and that they didn't want her to come back.’

‘But that's dreadful!’ I said, mortified.

‘Yes, I know.’ Edna shook her head sadly. ‘I don't know what's been going on. Mary and Ray said Donna had being trying to dominate the boys and boss them around, but I'm sure it was only her way of caring for them; Donna has spent all her life trying to look after the boys as best she could. But Warren and Jason, only a year apart in age, are glued to each other and present a united front. As they are so much brighter than Donna I wouldn't be surprised if they have been bullying her. I've seen them play tricks on her and use their intelligence to poke fun at her. I've told them off for it before. All the same, Cathy, I have to say, I was shocked by their attitude tonight. Donna loves them dearly and would do anything for them. It's probably for the best that they are being separated, for Donna's sake. She's not fair game for the boys. She's got a big heart, and I know she's a bit slow, but you would have thought brotherly love might have counted for something.’

‘Is Donna close to her older sister, Chelsea?’ I asked.

‘No. Chelsea and Mum are thick as thieves, and I'm beginning to think that Donna was out on a limb. You never really know what's going on in families behind closed doors. We brought the children into care because of severe physical neglect but emotional abuse is insidious and can be overlooked.’ She paused. ‘Anyway, Cathy, I'm sure Donna will be fine here. And when she does open up to you, I'd appreciate you telling me what she says.’

‘Yes, of course I will.’

‘Thanks. Let's get the car unpacked, and then I must get home to my hubby. He'll be thinking I've deserted him.’

Edna was truly a lovely lady and I could imagine her and her ‘hubby’ discussing their respective days in the comfort of their sitting room in the evening.

We made a number of journeys to and from the car, offloading a large suitcase, some cardboard boxes and a few carrier bags. Once we had stacked them in the hall, Edna said, ‘Right, Cathy, I'll say a quick goodbye to Donna then go.’

We returned to the lounge, where Donna was as we had left her on the sofa, head down and with the red paper bag containing her present clasped before her.

‘I'm off now,’ Edna said positively to Donna. ‘You have a good weekend and I'll phone Cathy on Monday; then I'll visit next week. If you need or want anything, ask Cathy and she will help you. And I think Paula is dying to make friends with you, so that will be nice.’

Edna stood just in front of Donna as she spoke but Donna didn't look up. ‘Come on,’ Edna encouraged kindly. ‘Stand up and give me a hug before I go.’

There was a moment's hesitation; then, with a small dismissive shrug, Donna stood and let Edna give her a hug, although I noticed she didn't return it. As soon as Edna let go, Donna sat down again. ‘Bye then, Donna,’ Edna said; then leaning out of the French windows, ‘Bye Adrian, Paula, have a good weekend.’

They both looked up and smiled. ‘Thank you.’

Edna collected her bag from where she'd left it beside the sofa and with a final glance at Donna — who was once more sitting head down with the present in her hands, and I thought trying hard to minimise Edna's departure — walked swiftly from the room.

‘Take care and good luck,’ Edna said to me as I saw her to the front door. ‘I'll phone first thing on Monday. And thanks, Cathy.’

‘You're welcome. Don't worry. She'll be fine,’ I reassured her again.

‘Yes,’ Edna said, and with a quick glance over her shoulder towards the lounge, went out of the door and down the path towards her car.

I closed the front door and returned to the lounge. ‘All right, love?’ I asked Donna as I entered.

She slightly, almost imperceptibly, shook her head and then I saw a large tear escape and roll down her cheek.

‘Oh love, don't cry,’ I said, going over and sitting next to her. ‘It won't seem so bad in the morning, I promise you, sweet.’

Another tear ran down her cheek and dripped on to the red paper bag in her lap, and then another. I put my arm around her and drew her to me. She resisted slightly, then relaxed against me. I held her close as tear after tear ran down her cheeks in silent and abject misery.

‘Here, love, wipe your eyes,’ I said softly, guiding her hand containing the tissue towards her face. She drew it across her eyes, then slowly lowered her head towards me, where it finally rested on my shoulder. I held her tight, and felt her head against my cheek as she continued to cry. ‘It's all right,’ I soothed quietly. ‘It will be all right, I promise you, love. Things will get better.’

Paula came in from the patio and, seeing Donna crying, immediately burst into tears. I took hold of her arm with my free hand and drew her to sit beside me on the sofa. I encircled her with my right arm while my left arm stayed around Donna.

‘Why's Donna crying?’ Paula asked between sobs.

‘Because a lot has happened today that has made her sad,’ I said, stroking Paula's cheek.

‘I don't like seeing people cry,’ Paula said. ‘It makes me cry.’

‘I know, love, and me. But sometimes it's good to have a cry: it helps let out the sad feelings. I think Donna will feel a bit better in a while.’ I remained where I was on the sofa with an arm around each of the girls, Paula sobbing her heart out on my right, Donna on my left, crying in silent misery, and me in the middle trying hard not to join in — for, like Paula, I can't stand seeing anyone upset, particularly a child.

Chapter Four Silence (#ulink_e1a67cb3-1c42-552a-be01-fd12c89fab25)

Adrian was not impressed. The phone had started ringing and, feeling unable to simply stand and desert the girls, I hadn't immediately answered it.

‘The phone's ringing,’ he said helpfully, coming in from the patio, with his Gameboy in his hand. He stopped as he saw the three of us and pulled a face, suggesting he didn't fully approve of this collective display of female emotion.

‘I'll answer it now,’ I said, throwing him a smile. ‘Everyone will be OK soon.’ This reassurance was enough for Adrian and he smartly nipped off into the garden, grateful he didn't have to be party to what must have appeared to a boy of his age to be blubbering nonsense.

I eased my arms from the girls and went to answer the phone on the corner unit. It was Jill.

‘You took a long time to answer. Is everything all right, Cathy?’

‘Yes. Donna is here.’ I glanced over to the sofa as Paula took up the gap I had left and snuggled into Donna's side. Donna lifted her arm and put it around Paula. ‘Yes, everything is fine,’ I said.

‘Cathy, I won't keep you now, as it's getting late. I just wanted to make sure Donna had arrived and there weren't any problems.’

‘No, no problems,’ I confirmed. ‘Edna only left ten minutes ago. She's going to phone you, and me, on Monday. She brought all the forms.’

‘Good. Well, enjoy your weekend. If you do need to speak to someone, Mike is back, and on call over the weekend; dial the emergency number.’

‘OK, Jill, thanks.’

‘And I'll phone on Monday, and visit as soon as I can next week.’

‘Fine,’ I said. We said goodbye and I hung up.

I glanced at the carriage clock on the mantelpiece. It was 7.40 p.m., after Paula's bedtime and getting close to Adrian and Donna's. I crossed over to the girls; they had both stopped crying now and Donna still had her arm around Paula. Both were sitting very still, as though appreciating the moment, although Paula was the only one to look at me.

‘Girls,’ I said gently, drawing up the footstool and squatting on it so that I was at their level. ‘Are you feeling a bit better now?’

Paula nodded and, with her head still resting against Donna, looked up at her. Donna had her head down and rubbed away the last of the tears from her cheeks with the tissue. I put a hand on each of their arms. ‘I think we will all feel better after a good night's sleep, and it is getting late,’ I said. Paula looked up again at Donna for her reaction, but there wasn't one: Donna remained impassive, head lowered, with the little red paper bag in her hand. ‘Donna, love, would you like something to eat?’ I asked again. ‘I have saved you dinner.’ She gave her head a little shake.

‘What about a drink before bed then?’

The same small shake of the head.

I hesitated, not really sure how to proceed. In many ways it was easier dealing with a child who was angry and shouting abuse: at least the pathway of communication at some level was open and could be channelled and modified. With so little coming back from Donna — she hadn't said a word yet — it was difficult to assess or interpret her needs. I hadn't thought to ask Edna if Donna had eaten, but even if the answer had been no, I could hardly force her to have dinner. ‘Are you sure you don't want anything to eat?’ I tried again. ‘Not even a snack?’

The same shake of the head, so I had to assume she wasn't hungry, and if she hadn't eaten she could make up for it at breakfast. ‘I'd love to see your present,’ I said, looking at the little bag. ‘So would Paula. Will you show us?’

Paula raised her head from Donna's side for a better view and Donna withdrew her arm. ‘What did Mary and Ray buy you?’ I asked. ‘I bet it's something nice.’

Very slowly and not raising her head, and with absolutely no enthusiasm, Donna moved her fingers and began to open the top of the paper bag. Paula and I watched as she dipped in her fingers and gradually drew out a bracelet made from small multi-coloured beads.

‘Oh, isn't that lovely,’ I said. ‘What a nice present.’

Donna cupped the bracelet in the palm of her hand, and I continued to enthuse, grateful for this small cooperation, which I viewed as progress. ‘Can you put it on your wrist and show us?’

Donna carefully slipped the bracelet over the fingers on her right hand and drew it down so that it settled around her wrist. As she did, I thought of Warren and Jason's parting shot, when they had told Donna not only that were they pleased she was going but not to go back. I felt so sorry for her.

‘That's beautiful,’ I said. I could tell that Donna was proud; she supported the wrist with the bracelet with her other hand, as though displaying it to its best advantage. It wasn't an expensive bracelet; it was the type of ‘infill’ present that one child gave another at a birthday party. The beads were painted plastic, strung together on elastic so that the bracelet fitted most-sized wrists. But if Paula thought the gift wasn't as precious as Donna did, she certainly didn't say so.

‘That is pretty,’ Paula said, touching it. ‘I like the red and blue ones.’ And I thought if anything typified the gaping chasm between children who had and those who did not, it was the bracelet. In our wealthy society with its abundance of acquirable material possessions, the gap between children from poor homes and those who enjoy all its advantages was widening. Paula had a couple of these bracelets, possibly three, and also a bedroom packed full of similar treasures which she'd received for Christmas and birthday presents, and treats from grandparents; but I knew from the way Donna cradled the bracelet that she certainly did not.

‘We will have to find a safe place for it in your bedroom,’ I said. Donna nodded.

I glanced at the clock again; I really had to start getting all three children upstairs and into bed. There was no way I was going to attempt Donna's unpacking now; it was too late, and we would have plenty of time the following day. ‘Now, love,’ I said, placing my hand on Donna's arm again. ‘We're going to take just what we need for tonight from your bags and sort out the rest in the morning, all right? Once you've had a good night's sleep everything will seem a lot better. I'd like you to come with me into the hall and tell me which bag has your nightwear and washing things.’ Then it occurred to me that Donna probably didn't know what each bag contained, as Edna had said Mary had done the packing that afternoon while Donna had been with Edna. ‘Do you know what's in each bag?’ I asked her.

Donna shrugged. ‘Wait there with Paula a minute,’ I said, ‘and I'll take a look, unless you want to come and help me?’

She shook her head, and I left her sitting with Paula, who was still, bless her, admiring the bracelet, while I went down the hall, hoping I wouldn't have to unpack every bag and case to find her night things. I peered in the various carrier bags and found that Mary had put everything Donna needed for the night in one plastic bag, presumably guessing it would be too late for us to unpack properly. Picking up this carrier bag, I returned to the lounge.

The girls were still together and Donna was slipping the bracelet from her wrist and returning it to the paper bag. ‘I've found what you need for tonight,’ I said. I went over and, opening the bag, showed her inside. ‘Nightdress, wash bag and teddy. Is there anything else you need, love?’

She shook her head.

The French windows were still open and Adrian was outside, now at the end of the garden having a last swing before he had to come in. It was nearly 8.30 p.m. and the air temperature was just starting to drop. ‘Adrian,’ I called from the step. ‘Five minutes, and then I want you to come in and get changed.’ He didn't say anything, but I knew he had heard me, for this scenario had been repeated most nights since school had broken up — I had left him playing in the garden, sometimes with the neighbour's children, while I got Paula ready for bed.

‘OK, girls,’ I said. ‘Let's go up and get you settled. Are you sure you wouldn't like a drink before you go, Donna?’

She shook her head.