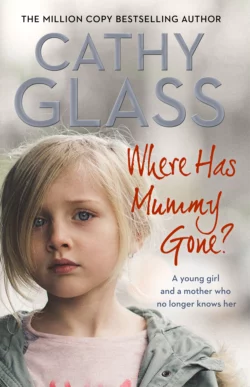

Where Has Mummy Gone?: A young girl and a mother who no longer knows her

Cathy Glass

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Семейная психология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 930.44 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The true story of Melody, aged 8, the last of five siblings to be taken from her drug dependent single mother and brought into care.When Cathy is told about Melody’s terrible childhood, she is sure she’s heard it all before. But it isn’t long before she feels there is more going on than she or the social services are aware of. Although Melody is angry at having to leave her mother, as many children coming into care are, she also worries about her obsessively – far more than is usual. Amanda, Melody’s mother, is also angry and takes it out on Cathy at contact, which again is something Cathy has experienced before. Yet there is a lost and vulnerable look about Amanda, and Cathy starts to see why Melody worries about her and feels she needs looking after.When Amanda misses contact, it is assumed she has forgotten, but nothing could have been further from the truth…